Abstract

Online racism is a digital social determinant to health inequity and an acute and widespread public health problem. To explore the heterogeneity of online racism exposure within and across race, we latent class modelled this construct among Asian (n = 310), Black (n = 306), and Latinx (n = 163) emerging adults in the United States and analysed key demographic and psychosocial health correlates. We observed Low and Mediated Exposure classes across all racial groups, whereas High Exposure classes appeared among Asian and Black people and the Systemic Exposure classes emerged uniquely in Asian and Latinx people. Generally, the High Exposure classes reported the greatest psychological distress and unjust views of society compared to all other classes. The Mediated and Systemic Exposure classes reported greater mental health costs than the Low Exposure classes. Asian women were more likely to be in the Mediated Exposure class compared to the Low Exposure class, whereas Black women were more likely to be in the Mediated Exposure class compared to both High and Low Exposure classes. About a third of each racial group belonged to the Low Exposure classes. Our findings highlight the multidimensionality of online racism exposure and identify hidden yet divergently risky subgroups. Research implications include examination of class membership chronicity and change over time, online exposure to intersecting oppressions, and additional antecedents and health consequences of diverse forms of online racism exposure.

Racism is prominent on the Internet and augmented by unique features of cyberspace (Keum, Citation2017; Keum & Miller, Citation2018; Tynes et al., Citation2018). For instance, factors including online anonymity and presuppositions of ‘digital freedom of speech’ may facilitate racist expressions by diffusing social conventions (e.g. accountability) that otherwise regulate in-person interactions (Keum & Miller, Citation2018). Mounting research links online racism with anxiety and depressive symptoms (Cano et al., Citation2021), psychological distress (Keum & Cano, Citation2021; Keum & Miller, Citation2017), PTSD symptoms (Maxie‐Moreman & Tynes, Citation2022), race-related hypervigilance (Keum & Li, Citation2022a), and substance use (Keum & Cano, Citation2021; Keum & Li, Citation2022a).

Despite these advances, less is known about the phenomenological nuance in how online racism exposure occurs. Whereas offline racism is encountered usually through direct verbal and behavioural discrimination, the dynamic terrain of online interactions and Internet content consumption (Marino et al., Citation2018; Verduyn et al., Citation2017) implies significant variability in type, extent, and patterns of racist exposure. Studies have identified profiles of social media use (e.g. active vs. passive) that differentiate how people interface reciprocally with online content (Frost & Rickwood, Citation2017; Verduyn et al., Citation2017). Exploring whether (and if so, how) patterns of online racism exposure varies within and across racially minoritized populations is imperative to identify subgroups at highest risk for its known deleterious health consequences. As such, we latent class analysed (LCA) unobserved heterogeneity in online racism exposure among Asian, Black, and Latinx emerging adults in the United States (U.S.) and modelled key psychosocial correlates across women and men.

Types and modes of online racism exposure

Keum and Miller (Citation2017) summarised that racially minoritized people experience online racism across three domains: (a) direct victimisation from personal online interactions, (b) vicarious exposure to online racist interactions and content, and (c) mediated exposure by online information that describes systemic racism and racially traumatising events (e.g. videos capturing racist hate crimes). Direct exposure often occurs in direct online interactions and can evoke immediate psychological distress. Vicarious and mediated exposures may occur through passive online engagement (e.g. as ‘bystanders’) yet precipitate gradual and sustained perceptual shifts in unjust views of society beyond emotional distress. Notably, studies on social media use and behavioural health mirror these trends. Active use (e.g. self-disclosing online, interacting with others, sharing content) is linked generally to positive outcomes (Verduyn et al., Citation2017), including greater perceived social support and reduced loneliness and depressive symptoms (Deters & Mehl, Citation2013; Frison & Eggermont, Citation2015). Conversely, passive use (e.g. browsing content, messages, profiles, etc.) is related to negative outcomes, including depressive and anxiety symptoms, body image issues, and alcohol use (Frost & Rickwood, Citation2017).

Type of online racism exposure may intersect with mode of Internet engagement to engender diverging health trajectories among racially minoritized people. For instance, active users may experience emotional distress incurred directly from racist online interactions, but they may also cope proactively by seeking online support, expressing their discontent publicly, and organising digital resistance to exact accountability upon the perpetrator(s). Inversely, passive users may avoid participating directly in racist online interactions but remain more vulnerable to uninterrupted vicarious and mediated exposures (i.e. where racist content flows one-way from originator to user and without feedback) and internalising their negative psychological impact. Active coping strategies for offline race-related stress—such as support seeking and counteraction—are indeed associated with better behavioural health outcomes than passive strategies (Keum & Li, Citation2022b), such as experiential avoidance and suppression (Brondolo et al., Citation2009).

Racial and gender differences in online racism exposure

Whereas direct online racism exposure may be common across Asian, Black, and Latinx populations (Keum & Miller, Citation2017), vicarious and mediated exposures may confer varying phenomenological valence in each group (Keum & Li, Citation2022a). Vicarious exposure is notable of the three domains considered as it explains unique variance in psychological distress beyond offline racism, suggesting that socially reflected yet passively apprehended racist experiences represent a distinct digital risk factor (Keum & Miller, Citation2017). Chae et al. (Citation2021) reported indeed that vicarious racism was associated with anxiety and depressive symptoms among Asian and Black adults. Lee-Won et al. (Citation2017) found likewise that Asian Americans drank alcohol to regulate the anger and shame precipitated by exposure to racist Twitter posts.

For Asian Americans, vicarious and mediated exposures comprise dehumanising narratives based in racializing ideologies (e.g. model minority myth, perpetual foreigner, yellow peril) as well as depictions of anti-Asian hate crimes perpetrated pervasively and especially against women (Keum et al., Citation2018) and the elderly (Lee et al., Citation2007) vis-à-vis the ongoing public health crisis of COVID-19 anti-Asian racism (Chen et al., Citation2020; Keum and Choi, Citation2022). For Black people, social media has unprecedently amplified the proliferation of racially traumatic content illustrating anti-Black hate crimes, police brutality, and other forms of systemic racist violence. The recent social media polarisation surrounding the murders of Breonna Taylor and George Floyd (Dreyer et al., Citation2020) represents a landmark example and such content is shown to induce vicarious trauma symptoms (Maxie‐Moreman & Tynes, Citation2022). For Latinx people, vicarious and mediated exposures may include racialised and xenophobic rhetoric that normalises anti-Latinx criminalisation, pathologizing, and scapegoating, which then motivate discriminatory policies (e.g. immigration law) and structural barriers that foster health, legal, and socioeconomic inequities (Buckner et al., Citation2022).

Finally, racially minoritized women may be particularly vulnerable to the negative health effects of online racism. Keum and Miller (Citation2018) found that Asian, Black, and Latinx women reported more vicarious and mediated exposures to online racism than men. Cyberbullying literature suggests similarly that girls and women are more likely to be victimised than their male counterparts given apparent differences in active vs. passive Internet use (Ang & Goh, Citation2010). The association among online racism and alcohol use appears stronger in racially minoritized women relative to men, which may be attributable partially to the confluence of racism and misogyny involved (Keum & Cano, Citation2021), suggesting a need for further subgroup analysis.

The present study

Motivated by these reviewed findings altogether, we conducted an LCA to identify patterns of online racism exposure among Asian, Black, and Latinx emerging adults in the U.S. and their differential links to key psychosocial health outcomes across women and men. Despite our exploratory study purpose, we anticipated that worse mental health would be associated with patterns involving vicarious and mediated exposures, as well as among women.

Method

Participants and procedure

We used a subsample from data collected in a previous study (Keum & Miller, Citation2017) that received IRB approval; see their report for participant demographics, sampling, and data inspection and preparation procedures. Our study sample mean age was 27.22 (SD = 9.61).

Measures

Perceived Online Racism Scale-Short Form

The 15-item Perceived Online Racism Scale-Short Form (PORS-SF) assesses participant exposure to racist online interactions and content (Keum Citation2021). The PORS-SF is a briefer version of the original 30-item PORS and retains the same 3-factor structure and construct validity evidence. The 3 subscales include 5 items each and are Personal Experience of Racial Cyberaggression (‘I have received posts with racist comments.’), Vicarious Exposure to Racial Cyberaggression (‘I have seen other racial/ethnic minority users being treated like a second-class citizen.’), and Online Mediated Exposure to Racist Reality (‘I have been informed about a viral/trending racist event happening elsewhere [e.g. in a different location].’). Participants respond on a 5-point Likert scale, 1 (never) to 5 (all the time). We used these items to estimate the LCA model after binarizing them to ease interpretation and presentation of the modelling results, to prevent overparameterization, and given the ancillary study scope of exploring person-level (vs. item-level) heterogeneity.

Mental Health Inventory-5

We measured participants’ psychological distress with the Mental Health Inventory-5 (MHI-5; Veit & Ware, Citation1983). The MHI-5 includes 5 items where higher scores indicate psychological well-being and lower scores indicate distress. Participants report on the frequency of the measured mental health-related feelings over the last month (e.g. ‘Have you felt downhearted and blue?’) using a 6-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (all of the time) to 6 (none of the time). Responses are summed and range from 5 to 30. For the current study, we reverse scored the items such that higher scores indicated higher psychological distress. See Fischer and Bolton Holz (Citation2010) for validity and reliability evidence. Alpha for our study was .85.

Perceived Stress Scale-10

We used the 10-item Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-10) to assess the extent to which participants perceived various life situations as stressful—that is, unpredictable, uncontrollable, and overloading—over the last month (Cohen et al., Citation1983). A sample item reads, ‘How often have you been angered because of things that were outside of your control?’ Participants respond on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (never) to 4 (very often). Responses are summed (ranging from 0 to 40), with higher total scores indicating greater perceived stress. See Cohen and Janicki-Deverts (Citation2012) for validity and reliability evidence. Alpha for our study was .86.

Unjust Views Scale

We used the 5-item Unjust Views Scale (UVS; Lench & Chang, Citation2007) to assess personal (‘The awful things that happen to me are unfair.’) and general (‘People who do evil things get away with it.’) beliefs about an unfair world. Participant responses can range from 1 (strongly agree) to 5 (strongly disagree). Responses are summed and averaged, where lower scores indicate greater belief in an unjust world. See Lench and Chang (Citation2007) and Liang and Borders (Citation2012) for validity evidence. Alpha for our study was .65.

Data analysis

We estimated all models with Mplus 8.0 (Muthén & Muthén, Citation1998–2017) and separately for each racial group—Asian, Black, and Latinx—to investigate unconstrainedly their distinct racialisation experiences. LCAs analyse the joint distribution of a set of observed variables as a function of a finite, exhaustive, and mutually exclusive set of latent classes that reflect ‘hidden groups’ of people that diverge qualitatively in their item response patterns (Masyn, Citation2013). Model indicators are in and derived from Keum (Citation2021). See Nylund-Gibson and Choi (Citation2018) for a comprehensive overview and applied tutorial of LCA.

Table 1. List of model indicators.

We followed recommended class enumeration procedures from Masyn (Citation2013). We used FIML with robust standard errors and a large number of random starts to attain global maxima and avoid convergence on local solutions (McLachlan & Peel, Citation2000). We first fitted a one-class model and increased the number of classes progressively to assess whether each added class produced conceptually and statistically superior solutions. We terminated enumeration after finding nonconvergent models (e.g. an indication of overparameterization).

To decide on the final number of classes, we considered multiple fit statistics holistically (Masyn, Citation2013; Nylund et al., Citation2007). First, we used approximate fit criteria—the Bayesian information criterion (BIC), sample size adjusted Bayesian information criterion (SABIC), consistent Akaike information criterion (CAIC), and approximate weight of evidence criterion (AWE)—where lower values denote better fit. Second, we used likelihood tests—the bootstrapped likelihood ratio test (BLRT) and the Vuong-Lo-Mendell-Rubin adjusted likelihood ratio test (VLMR LRT)—whose p-values assess whether adding a class (k) improves fit compared to a solution with one fewer class (k − 1). Third, we used the Bayes factor (BF), which compares fit among two adjacent models, where 1 < BF < 3 suggests ‘weak’ support for the model with fewer classes, 3 < BF < 10 suggests ‘moderate’ support, and BF > 10 suggests ‘strong’ support. Fourth, we used the correct model probability (cmP), choosing the model with the highest value among all considered. Finally, we assessed the substantive validity of the candidate models by inspecting their conditional item probabilities visually, privileging parsimony as appropriate to avoid potentially overextracting classes given the small sizes of our racial subsamples (Nylund-Gibson & Choi, Citation2018). After selecting the final model, we reviewed entropy, an omnibus index where values > .80 indicate ‘good’ overall classification of cases into classes (See Masyn (Citation2013) for a detailed treatment of LCA fit indices).

With the chosen LCA model for each racial group, we estimated a binary gender covariate and three distal outcome variables—the MHI-5, PSS-10, and UVS (described in Measures)—of class membership. We used the Bolck, Croon, and Hagenaars (BCH) method (Asparouhov & Muthén, Citation2014; Bolck et al., Citation2004; Vermunt, Citation2010), a sequential strategy recommended to preserve the integrity of the emergent latent class variable when analysing auxiliary variables (Nylund-Gibson et al., Citation2019; Nylund-Gibson & Masyn, Citation2016) and to account for person-level classification error. Here, we also included two control variables—time spent on the Internet and self-reported extent of reliance on the Internet as a resource—to account for extraneous individual differences in Internet use, and a sensitivity analysis revealed no perturbance to the emergent classes. We then regressed the latent class variable on the covariate with multinomial logistic regression to examine whether class proportions were equivalent across gender. We estimated the distal outcomes controlling for the centred covariate representing the relative proportion of genders, which eased interpretation.

Results

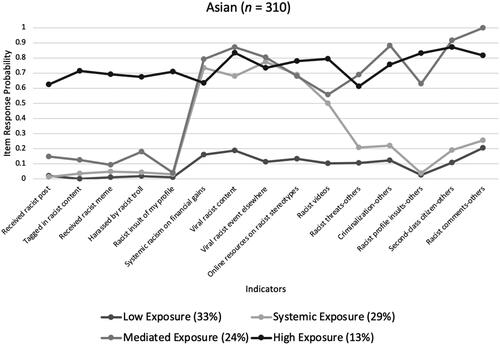

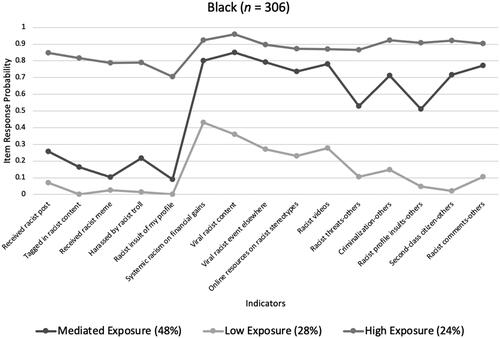

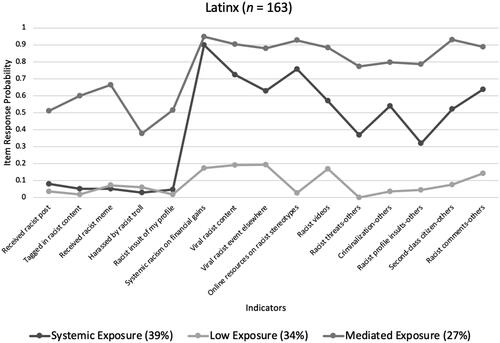

All fit statistics and conditional item probabilities are illustrated in and , respectively. We evaluated and interpreted LCA solutions separately for each racial group. For classes that emerged with similar functional form across race, we used uniform labels for consistency and to facilitate cross-racial comparison. When interpreting classes, we reviewed the conditional item probabilities for class homogeneity—where values < .30 and > .70 reflect high homogeneity—to identify indicators that independently or jointly with others epitomised each class (Masyn, Citation2013).

Table 2. Fit statistics: Unconditional latent class analysis models.

Table 3. Conditional item probabilities across latent classes by race.

In the proceeding sections, we report statistically significant (p < .05) auxiliary relations for each racial group. For the distal outcomes (see ), we used each of the latent classes as a reference class for pairwise comparisons.

Table 4. Distal outcomes by latent classes across race.

Asian (n = 310)

Most indices—the BIC, CAIC, AWE, VLMR LRT, BF, and cmP—supported a 4-class model. The SABIC supported a 5-class model while the BLRT was not informative. Given these, we selected the 4-class model.

illustrates the item probability plot for Asian people. We labelled the largest class ‘Low Exposure’ (33%) given uniformly low levels of exposure across all indicators. We labelled the second largest class ‘Systemic Exposure’ (29%) given its characteristic elevation in online exposure to racist reality but low endorsement of directly and vicariously perceived racial cyberaggressions in online interactions. We labelled the third largest class ‘Mediated Exposure’ (24%) given its definitive elevation across online exposure to racist reality and vicariously perceived racial cyberaggressions, but low endorsement of directly perceived racial cyberaggressions. We labelled the smallest class ‘High Exposure’ (13%) given generally high endorsement across all indicators. The 4-class model entropy was .83, above the suggested cut-off to indicate well-separated classes.

Men were less likely than women to be in the Mediated Exposure class relative to the Low Exposure class, OR = .351 (.172, .716). The High Exposure class endorsed greater PSS-10, MHI-5, and UVS compared to all other classes. The Mediated Exposure class endorsed higher PSS-10 compared to the Low Exposure class.

Black (n = 306)

The CAIC, AWE, and VLMR LRT supported a 3-class model. The BIC, BF, and cmP supported a 4-class model. The SABIC supported a 5-class model while the BLRT was not informative. We reviewed the 3- and 4-class models as candidate solutions and decided on the 3-class model for parsimony and interpretability.

illustrates the item probability plot for Black people. We labelled the largest class ‘Mediated Exposure’ (48%) given its definitive elevation across online exposure to racist reality and vicariously perceived racial cyberaggressions in online interactions, but low endorsement of directly perceived racial cyberaggressions. We labelled the second largest class ‘Low Exposure’ (28%) given relatively low levels of endorsement across all indicators, excepting moderate endorsement of exposure to racist content related to financial gains. We labelled the smallest class ‘High Exposure’ (24%) given generally high endorsement across all indicators. The 3-class model entropy was .87, above the suggested cut-off to indicate well-separated classes.

Men were less likely than women to be in the Mediated Exposure class relative to the High Exposure, OR = .509 (.261, .991) and Low Exposure, OR = .378 (.201, .708) classes. The High Exposure class endorsed higher PSS-10 and MHI-5 compared to all other classes. The High Exposure class endorsed greater UVS compared to the Low Exposure class. The Mediated Exposure class endorsed greater PSS-10, MHI-5, and UVS compared to the Low Exposure class.

Latinx (n = 163)

The BIC, CAIC, VLMR LRT, and cmP supported a 3-class model. The SABIC supported a 5-class model, whereas the AWE suggested a 2-class model, and the BLRT supported a 4-class model. The BF supported the range of 3- to 4-class models. Given these, we decided on the 3-class model.

illustrates the item probability plot for Latinx people. We labelled the largest class ‘Systemic Exposure’ (39%) given its characteristic elevation in online exposure to racist reality but low endorsement of directly and vicariously perceived racial cyberaggressions in online interactions. We labelled the second largest class ‘Low Exposure’ (34%) given uniformly low levels of exposure across all indicators. We labelled the smallest class ‘Mediated Exposure’ (27%) given its definitive elevation across online exposure to racist reality and vicariously perceived racial cyberaggressions, with chance-level endorsement of directly perceived racial cyberaggressions, including a moderately high likelihood of having encountered a racist meme.

The 3-class model entropy was .89, above the suggested cut-off to indicate well-separated classes.

The Mediated Exposure class endorsed greater PSS-10 and UVS compared to the Low Exposure class and higher MHI-5 compared to all other classes. The Systemic Exposure class endorsed greater PSS-10 and UVS compared to the Low Exposure class.

Discussion

Online racism is a digital determinant to health inequity and an acute and widespread public health problem. To explore the heterogeneity of online racism exposure within and across race, we latent class modelled this construct among Asian, Black, and Latinx adults in the U.S. and analysed key demographic and psychosocial health correlates. Our results extended evidence supporting the assertion that online racism exposure manifests in multiple and well-distinguished forms that vary qualitatively in both the degree and type of online racism encountered. Regarding health consequences, our analyses and interpretation aligned with social media scholarship attesting that how Internet users engage reciprocally with online content matters above and beyond the absolute amounts of content consumed or time spent online. We also demonstrated the utility of LCA for investigating with more granularity and nuance the multidimensionality of online racism exposure and identifying the riskiest subgroups.

Racially minoritized people appear to diverge categorically and systematically in their experience of online racism where this variation confers differential psychosocial health outcomes. We observed Low and Mediated Exposure classes across all racial groups, whereas High Exposure classes appeared among Asian and Black people and the Systemic Exposure classes emerged uniquely in Asian and Latinx people. Generally, the High Exposure classes reported the greatest psychological distress and unjust views of society compared to all other classes. The Mediated and Systemic Exposure classes reported greater mental health costs than the Low Exposure classes. Promisingly, about a third of each racial group belonged to the Low Exposure classes. These cross-racial similarities and differences in class formation suggest an experiential duality wherein some operative commonality and shared psychological burden of online racial oppression functions alongside racialisation processes specific to each racial group.

High Exposure

Unsurprisingly, those in the High Exposure classes were at greatest risk for psychological distress, unjust views of society, and poor mental health. Racially minoritized people in these classes reported encountering online racism frequently and across all indicators of exposure. Moreover, this pattern was prominent among Asian and Black people, likely reflecting the contemporary pervasiveness of anti-Asian (Lee-Won et al., Citation2017) and anti-Black (Dreyer et al., Citation2020) racism in cyberspace and portending a societal normalisation of publicly expressed racial abuse, discrimination, essentialism, and ignorance online and offline against these groups. Indeed, almost a quarter of our Black sample was in the High Exposure class, consistent with the social media proliferation of racially traumatic content illustrating anti-Black interpersonal and structural violence (Volpe et al., Citation2021). That said, it is also likely that our limited Latinx sample size prevented the relatively smaller High Exposure class (and other potential classes) from emerging in this group—a point for future study.

The comprehensiveness of online racism exposure exhibited by the High Exposure classes suggests that their members may use the Internet both actively and passively (Frost & Rickwood, Citation2017; Verduyn et al., Citation2017). Although research shows that active use is associated with benefits including social support and community building (Verduyn et al., Citation2017), our findings proffer alternatively yet tentatively that it may heighten psychological risk in racialised online contexts. For example, such users may be more likely to encounter additional avenues containing evermore ‘creative,’ extreme, and/or novel forms of racial cyberaggression that generate psychological overwhelm and mitigate the salubrious effects of active online behaviour purported in the first place. Indeed, an important psychological aspect of online racism is its continuous yet random, multimodal, and unexpected occurrence over the course of daily online interactions (Keum & Miller, Citation2018) akin to racial battle fatigue (Smith, Citation2014).

Mediated Exposure

Typically, the Mediated Exposure classes endorsed high vicarious exposure to racist online interactions (e.g. observing other racially minoritized people being victimised) and consumption of online material that exposes the reality of systemic racism in society (e.g. viral racist content) and low levels of direct online racism (e.g. receiving racist messages), suggesting altogether that they are more likely to be passive Internet users. Black and Latinx people in the Mediated Exposure classes reported significantly more psychological distress and unjust views of society compared to the Low Exposure classes. Among these racial groups, passive use (Frost & Rickwood, Citation2017) may indeed increase one’s tendency to internalise negative responses to racism and precipitate behavioural health problems (Gaylord-Harden and Cunningham, Citation2009), including coping-motivated alcohol use (Pittman et al., Citation2019). Asian women were also more likely to be in this class compared to the Low Exposure class, whereas Black women were more likely to be in this class compared to both High and Low Exposure classes. These trends conform with prior notation that women are more likely to be victimised passively by cyberaggression. For instance, Keum and Cano (Citation2021) found that racially minoritized women experienced unique social media-related stress compared to men, which predicted their alcohol use severity.

Sustained exposure to online material that expounds the reality of systemic racism and everyday racial dehumanisation may reshape and/or worsen perceptions of society among racially minoritized people and to their mental health detriment. Notably, about a quarter of our Asian and Latinx samples respectively and almost half of our Black sample belonged to the Mediated Exposure classes. Liang and Borders (Citation2012) reported that racial discrimination may evoke or exacerbate an unjust view of society which can then destabilise psychological functioning. Keum and Li (Citation2022a) showed similarly that online racism predicted anticipatory race-related vigilance, an outcome that reflects an (accurate) appraisal of society as racially hostile and unsafe. These findings corroborate ours to indicate an emerging digital inequity that exacts a disproportionate phenomenological burden on racially minoritized people, whereby an all-encompassing, inescapable, yet normalised cyberspacetime of racism exposure may potentiate a psychiatrically deleterious worldview of anomie, disempowerment, and pessimism.

Systemic Exposure

Finally, the emergence of the Systemic Exposure classes among Asian and Latinx people suggests that acculturative dynamics may meaningfully configure online racism experiences. For instance, the salience of exposure to content describing structural racial inequities (e.g. racial/ethnic minorities earning less money than whites for doing the same work) in these classes may reflect how societal barriers to cultural inclusion and socioeconomic security encountered by Asian and Latinx people often derive from their shared racialisation as perpetual foreigners or even external invaders to the white nation-state (Buckner et al., Citation2022; Keum et al., Citation2018). Many Asian and Latinx people may also reside in ethnocultural enclaves—both online and offline—that provide some (and perhaps precisely for) protection against direct and vicarious racist cyberaggressions, but not necessarily regarding their sensitised preoccupation about prospects for full civic participation and representation in mainstream U.S. society.

Interestingly, membership in the Systemic Exposure classes compared to the Low Exposure classes conferred negative mental health effects among Latinx but not Asian people. We speculate that the psychological impact of structural stigma (Hatzenbuehler, Citation2016) may be perceived more unambiguously among Latinx people, whereas the model minority myth—associated more prominently with and internalised by many Asian Americans (Chou & Feagin, Citation2015)—may obfuscate the latter’s ability to correctly apprehend the reality and personal applicability of structural racism and thus moderate the emotional consequences of Systemic Exposure. Altogether, these findings denote that cross-racial variation in psychiatric vulnerability linked with more ‘distal’ forms of online racism exposure is nuanced and requires further investigation.

Limitations and future research directions

Our findings should be reviewed with several limitations. First, our small sample size and exploratory study purpose render our conclusions ancillary. Future studies should validate our classes of online racism exposure through replication and longitudinal designs. Notably, we analysed data collected before the COVID-19 pandemic and the 2020 racial uprisings; these events represent nonignorable history effects as they transformed the collective consciousness among many racially minoritized people in how they understand and interface with online (and offline) racism, with particular implications for the Mediated and Systemic Exposure classes. We thus encourage models that use more recent data and which examine chronicity and change in class membership over time (Nylund, Citation2007). Studies should likewise explore and compare online racism exposure patterns among racial groups uninvestigated herein.

Second, future work should conduct expanded and more refined mixture analyses, including auxiliary relations. We analysed binary gender as a covariate to account for salient online behavioural differences noted previously in this regard. We suggest more research that models classes within women and men of colour separately given increasing empirical recognition of significant experiential differences based in gendered racial socialisation (e.g. Thomas & King, Citation2007). Similarly, we look forward to scholarship that examines patterns of online exposure to multiple and intersecting forms of oppression (e.g. classism, heterosexism) alongside racism.

Finally, we extended evidence regarding the influence of online racism exposure patterns on several psychosocial health outcomes, and researchers should examine additional predictors and consequences of class membership. For example, we controlled for two major sources of individual differences in general Internet use—time spent on the Internet and the extent to which participants relied on the Internet as a resource—but the literature indicates that Internet (e.g. social media) usage characteristics are more complex and diverse in their expression and how they precipitate diverging behavioural health trajectories. The interface among patterns of generic online behaviour—including dispositional and contextual correlates—and online racism exposure should be explored further to better characterise racially minoritized people in vulnerable and more adaptive classes. Such work will assist to delineate risk and protective factors regarding the psychologically nefarious terrain of online racism and overlapping forms of social injustice.

Conclusion

We examined unobserved heterogeneity in online racism exposure among Asian, Black, and Latinx emerging adults in the U.S. and analysed key demographic and psychosocial health correlates. Latent class modelling revealed multiple distinguishable profiles (High, Mediated, Systemic, and Low Exposure) within and across racial groups that varied in both degree and type of online racism encountered, irrespective of time spent on the Internet and personal reliance on it. Those in High and Mediated Exposure classes were at greater risk for mental health issues, while Systemic Exposure emerged as a unique profile for Asian and Latinx groups. Our auxiliary relations conformed to past scholarship, where women appeared to be particularly vulnerable to mental health issues associated with Mediated Exposure to online racism. Finally, we demonstrated the utility of LCA for describing how racially minoritized people diverge categorically and systematically in their experience of online racism, the relations thereof to differential health consequences, and implications for identifying adaptive and risker subgroups affected by the growing digital inequity driven by online racism.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval for the study was granted by the Institutional Review Board.

Author contributions

Brian TaeHyuk Keum: Conceptualisation, Methodology, Software, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Visualisation. Andrew Young Choi: Methodology, Software, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Visualisation.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Not applicable as this study reports on secondary data analysis.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ang, R. P., & Goh, D. H. (2010). Cyberbullying among adolescents: The role of affective and cognitive empathy, and gender. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 41(4), 387–397. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-010-0176-3

- Asparouhov, T., & Muthén, B. (2014). Auxiliary variables in mixture modeling: Three-step approaches using Mplus. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 21(3), 329–341. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705511.2014.915181

- Bolck, A., Croon, M., & Hagenaars, J. (2004). Estimating latent structure models with categorical variables: One-step versus three-step estimators. Political Analysis, 12(1), 3–27. https://doi.org/10.1093/pan/mph001

- Brondolo, E., Brady Ver Halen, N., Pencille, M., Beatty, D., & Contrada, R. J. (2009). Coping with racism: A selective review of the literature and a theoretical and methodological critique. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 32(1), 64–88. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-008-9193-0

- Buckner, J. D., Lewis, E. M., Shepherd, J. M., & Zvolensky, M. J. (2022). Ethnic discrimination and alcohol-related problem severity among Hispanic/Latin drinkers: The role of social anxiety in the minority stress model. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 138, 108730. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2022.108730

- Cano, M. Á., Schwartz, S. J., MacKinnon, D. P., Keum, B. T. H., Prado, G., Marsiglia, F. F., Salas-Wright, C. P., Cobb, C. L., Garcini, L. M., De La Rosa, M., Sánchez, M., Rahman, A., Acosta, L. M., Roncancio, A. M., & de Dios, M. A. (2021). Exposure to ethnic discrimination in social media and symptoms of anxiety and depression among Hispanic emerging adults: Examining the moderating role of gender. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 77(3), 571–586. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.23050

- Chae, D. H., Yip, T., Martz, C. D., Chung, K., Richeson, J. A., Hajat, A., Curtis, D. S., Rogers, L. O., & LaVeist, T. A. (2021). Vicarious racism and vigilance during the COVID-19 pandemic: Mental health implications among Asian and Black Americans. Public Health Reports, 136(4), 508–517. https://doi.org/10.1177/00333549211018675

- Chen, J. A., Zhang, E., & Liu, C. H. (2020). Potential impact of COVID-19–related racial discrimination on the health of Asian Americans. American Journal of Public Health, 110(11), 1624–1627. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2020.305858

- Chou, R. S., & Feagin, J. R. (2015). Myth of the model minority: Asian Americans facing racism. Routledge.

- Cohen, S., & Janicki-Deverts, D. (2012). Who’s stressed? Distributions of psychological stress in the United States in probability samples from 1983, 2006, and 20091. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 42(6), 1320–1334. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2012.00900.x

- Cohen, S., Kamarck, T., & Mermelstein, R. (1983). A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 24(4), 385–396. https://doi.org/10.2307/2136404

- Deters, F. G., & Mehl, M. R. (2013). Does posting Facebook status updates increase or decrease loneliness? An online social networking experiment. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 4(5), 579–586. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550612469233

- Dreyer, B. P., Trent, M., Anderson, A. T., Askew, G. L., Boyd, R., Coker, T. R., Coyne-Beasley, T., Fuentes-Afflick, E., Johnson, T., Mendoza, F., Montoya-Williams, D., Oyeku, S. O., Poitevien, P., Spinks-Franklin, A. A. I., Thomas, O. W., Walker-Harding, L., Willis, E., Wright, J. L., Berman, S., … Stein, F. (2020). The death of George Floyd: Bending the arc of history toward justice for generations of children. Pediatrics, 146(3), e2020009639. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2020-009639

- Fischer, A. R., & Bolton Holz, K. (2010). Testing a model of women’s personal sense of justice, control, well-being, and distress in the context of sexist discrimination. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 34(3), 297–310. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.2010.01576.x

- Frison, E., & Eggermont, S. (2015). The impact of daily stress on adolescents’ depressed mood: The role of social support seeking through Facebook. Computers in Human Behavior, 44, 315–325. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.11.070

- Frost, R. L., & Rickwood, D. J. (2017). A systematic review of the mental health outcomes associated with Facebook use. Computers in Human Behavior, 76, 576–600. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.08.001

- Gaylord-Harden, N. K., & Cunningham, J. A. (2009). The impact of racial discrimination and coping strategies on internalizing symptoms in African American youth. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 38(4), 532–543. 10.1007/s10964-008-9377-5 19636726

- Hatzenbuehler, M. L. (2016). Structural stigma: Research evidence and implications for psychological science. The American Psychologist, 71(8), 742–751. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000068

- Keum, B. T. (2017). Qualitative Examination on the Influences of the Internet on Racism and its Online Manifestation. International Journal of Cyber Behavior, Psychology and Learning, 7(3), 13–22. 10.4018/IJCBPL.2017070102

- Keum, B. T., & Choi, A. Y. (2022). COVID-19 Racism, Depressive Symptoms, Drinking to Cope Motives, and Alcohol Use Severity Among Asian American Emerging Adults. Emerging Adulthood, 10(6), 1591–1601. 10.1177/21676968221117421

- Keum, B. T., Brady, J. L., Sharma, R., Lu, Y., Kim, Y. H., & Thai, C. J. (2018). Gendered Racial Microaggressions Scale for Asian American Women: Development and initial validation. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 65(5), 571–585. 10.1037/cou0000305 30058827

- Keum, B. T. (2021). Development and validation of the Perceived Online Racism Scale short form (15 items) and very brief (six items). Computers in Human Behavior Reports, 3, 100082. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chbr.2021.100082

- Keum, B. T. H., & Cano, M. Á. (2021). Online racism, psychological distress, and alcohol use among racial minority women and men: A multi-group mediation analysis. The American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 91(4), 524–530. https://doi.org/10.1037/ort0000553

- Keum, B. T., & Li, X. (2022b). Coping with online racism: Patterns of online social support seeking and anti-racism advocacy associated with online racism, and correlates of ethnic-racial socialization, perceived health, and alcohol use severity. PloS One, 17(12), e0278763. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0278763

- Keum, B. T., & Miller, M. J. (2017). Racism in digital era: Development and initial validation of the Perceived Online Racism Scale (PORS v1.0). Journal of Counseling Psychology, 64(3), 310–324. https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000205

- Keum, B. T., & Miller, M. J. (2018). Racism on the Internet: Conceptualization and recommendations for research. Psychology of Violence, 8(6), 782–791. https://doi.org/10.1037/vio0000201

- Keum, B. T., & Li, X. (2022a). Online racism, rumination, and vigilance: Impact on distress, loneliness, and alcohol Use. The Counseling Psychologist, 0(0).https://doi.org/10.1177/00110000221143521

- Lee, Y. T., Vue, S., Seklecki, R., & Ma, Y. (2007). How did Asian Americans respond to negative stereotypes and hate crimes? American Behavioral Scientist, 51(2), 271–293. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764207306059

- Lee-Won, R. J., Lee, J. Y., Song, H., & Borghetti, L. (2017). “To the bottle I go… to drain my strain”: Effects of microblogged racist messages on target group members’ intention to drink alcohol. Communication Research, 44(3), 388–415. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650215607595

- Lench, H. C., & Chang, E. S. (2007). Belief in an unjust world: When beliefs in a just world fail. Journal of Personality Assessment, 89(2), 126–135. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223890701468477

- Liang, C. T., & Borders, A. (2012). Beliefs in an unjust world mediate the associations between perceived ethnic discrimination and psychological functioning. Personality and Individual Differences, 53(4), 528–533. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2012.04.022

- Marino, C., Gini, G., Vieno, A., & Spada, M. M. (2018). The associations between problematic Facebook use, psychological distress and well-being among adolescents and young adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 226, 274–281. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2017.10.007

- Masyn, K. E. (2013). Latent class analysis and finite mixture modeling. In T. D. Little (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of quantitative methods: Vol. 2: Statistical analysis (pp. 551–611). Oxford University Press.

- Maxie‐Moreman, A. D., & Tynes, B. M. (2022). Exposure to online racial discrimination and traumatic events online in Black adolescents and emerging adults. Journal of Research on Adolescence: The Official Journal of the Society for Research on Adolescence, 32(1), 254–269. https://doi.org/10.1111/jora.12732

- McLachlan, G., & Peel, D. (2000). Finite mixture models. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. (1998–2017). Mplus user’s guide. (8th ed.). Muthén & Muthén.

- Nylund, K. L. (2007). Latent transition analysis: Modeling extensions and an application to peer victimization [Doctoral dissertation], University of California, Los Angeles.

- Nylund, K. L., Asparouhov, T., & Muthén, B. O. (2007). Deciding on the number of classes in latent class analysis and growth mixture modeling: A Monte Carlo simulation study. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 14(4), 535–569. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705510701575396

- Nylund-Gibson, K., & Choi, A. Y. (2018). Ten frequently asked questions about latent class analysis. Translational Issues in Psychological Science, 4(4), 440–461. https://doi.org/10.1037/tps0000176

- Nylund-Gibson, K., & Masyn, K. E. (2016). Covariates and mixture modeling: Results of a simulation study exploring the impact of misspecified effects on class enumeration. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 23(6), 782–797. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705511.2016.1221313

- Nylund-Gibson, K., Grimm, R. P., & Masyn, K. E. (2019). Prediction from latent classes: A demonstration of different approaches to include distal outcomes in mixture models. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 26(6), 967–985. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705511.2019.1590146

- Pittman, D. M., Brooks, J. J., Kaur, P., & Obasi, E. M. (2019). The cost of minority stress: Risky alcohol use and coping-motivated drinking behavior in African American college students. Journal of Ethnicity in Substance Abuse, 18(2), 257–278. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332640.2017.1336958

- Smith, W. A. (2014). Racial battle fatigue in higher education: Exposing the myth of post-racial America. Rowman & Littlefield.

- Thomas, A. J., & King, C. T. (2007). Gendered racial socialization of African American mothers and daughters. The Family Journal, 15(2), 137–142. https://doi.org/10.1177/1066480706297853

- Tynes, B. M., Lozada, F. T., Smith, N. A., & Stewart, A. M. (2018). From racial microaggressions to hate crimes: A model of online racism based on the lived experiences of adolescents of color. In G. C. Torino, D. P. Rivera, C. M. Capodilupo, K. L. Nadal, & D. W. Sue (Eds.), Microaggression theory: Influence and implications (pp. 194–212). John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- Veit, C. T., & Ware, J. E. (1983). The structure of psychological distress and well-being in general populations. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 51(5), 730–742. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.51.5.730

- Verduyn, P., Ybarra, O., Résibois, M., Jonides, J., & Kross, E. (2017). Do social network sites enhance or undermine subjective well-being? A critical review. Social Issues and Policy Review, 11(1), 274–302. https://doi.org/10.1111/sipr.12033

- Vermunt, J. K. (2010). Latent class modeling with covariates: Two improved three-step approaches. Political Analysis, 18(4), 450–469. https://doi.org/10.1093/pan/mpq025

- Volpe, V. V., Hoggard, L. S., Willis, H. A., & Tynes, B. M. (2021). Anti-Black structural racism goes online: A conceptual model for racial health disparities research. Ethnicity & Disease, 31(Suppl 1), 311–318. https://doi.org/10.18865/ed.31.S1.311