Abstract

This paper describes the current understanding of the psychodynamics of the pathway to suicide and argues that the limitations of current epidemiological and observational approaches often overlook crucial psychodynamic factors. It describes how an underlying vulnerability in the capacity to process emotions can lead to unbearable pain, where death is perceived as the only escape. The intense emotional states following life’s losses can then precipitate a profound division within the self. This internal split is characterised by a detached, destructive ‘perpetrator’ aspect and a vulnerable ‘victim’ aspect, with the former often overpowering the latter in the lead-up to suicide through suicidal fantasies of life after death. Drawing on data from various sources, including case studies, mental health audits, and coroner’s reports, the paper assesses the practical efficacy of understanding suicide through a psychodynamic lens. This approach aims to provide more effective intervention strategies, not just by preventing suicide but also by addressing the needs of those left bereaved, who often suffer from complex grief and an elevated risk of suicide themselves. By shifting focus from solely preventive measures to a deeper understanding of the underlying psychological mechanisms, this research advocates for a more holistic approach to suicide prevention. It calls for a shared philosophical inquiry into the nature of human existence and the existential conflict between the will to live and the impulse to die, suggesting that a more nuanced comprehension of these dynamics could lead to better support systems both for those at risk and those bereaved.

Introduction

… killing yourself amounts to confessing.. that life is too much for you or that you do not understand it…. Dying voluntarily implies that you have recognised, even instinctively, … the absence of any profound reason for living, the insane character of that daily agitation and the uselessness of suffering.

Camus (Citation1942)

Suicide brings to the fore important philosophical questions about life and what it means to be human. It embodies the conflict at the heart of existence, that is how to both live and die. In the UK it stands as the leading cause of death for all those under 35 and for men under 50 (ONS, Citation2023). It is a shocking and disturbing death for those bereaved, who are left with complex bereavement, an increased risk of suicide, unanswerable questions, and shattered lives (Pitman, Citation2014; Gibbons, Citation2024).

Over the past two decades in the UK, the decrease in stigma surrounding suicide has led to the rise of a strong and creative suicide prevention movement, drawing widespread interest, significant funding, and support. However, it is arguable that despite these efforts, the initiatives have not reaped clear rewards in the form of sustained rate reductions over this same time period (NCISH, Citation2023). This reality urges us to engage in critical reflection: Are we overlooking something? In our heartfelt efforts to reduce the suicide rate, are we perhaps subconsciously avoiding certain crucial aspects? Might we be mirroring the ambivalence of those in a suicidal state by trying to both confront and evade the issue at the same time?

The prevailing wisdom seems to be that to succeed in suicide prevention we need to intensify our efforts—judge more critically where there have been shortcomings, set even stricter goals (aim for zero suicide), and apply more pressure. However, there is an alternative, which is to turn our attention directly towards trying to understanding the mental mechanisms that underly the act. By deepening our comprehension of what drives an individual to conclude their life in this manner we may be able to provide realistic intervention strategies. This approach could also unite us in a shared philosophical inquiry, where we explore the challenge of what it means to be human.

Despite the evidence that individual suicide has very limited predictability (Gibbons, Citation2023), much contemporary suicide research and intervention continues to be predicated on this assumption, shaping both the methodology used and the interpretation of results. Present day hypotheses about suicide are primarily informed by epidemiological and observational data, offering scant understanding of the psychodynamics. This method is analogous to attempting mitigate deaths from heart disease by concentrating on the demographics of the deceased and the circumstances of their death, rather than investigating the underlying biological and physiological mechanisms of the illness. We must ask ourselves, how can we initiate meaningful change without a deeper understanding of the underlying issues?

This paper aims to address this question by examining the psychological pathway to suicide as defined by contemporary psychoanalysts such as Campbell and Hale (UK) and Maltzberger (USA). Its practical applicability will be assessed using data from diverse sources, including: research findings, narratives from those bereaved by suicide, accounts from survivors of serious suicide attempts, audits conducted by mental health organisations, data provided by the police, and analyses of coroners’ records. The objective is to shed light on the destructive forces that underpin and precipitate these events and thereby inform practical mitigation strategies, assist professionals, sooth those enduring suicidal distress, and to provide some explanation to those bereaved.

This paper is the third in a series of three. The first, ‘Eight “Truths” about Suicide’, examined the nature of suicide (https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/bjpsych-bulletin/article/eight-truths-about-suicide/36D1872261E290945E245143BECC6260), and the second, ‘Someone Is to Blame: The Impact of Suicide on the Mind of the Bereaved (Including Clinicians)’ explored why a death by suicide profoundly affects those bereaved (link will be available in a week, www.cambridge.org/core/journals/bjpsych-bulletin).Footnote1

Words marked with an asterix* are defined in .

Table 1. Definitions of terms used throughout the paper.

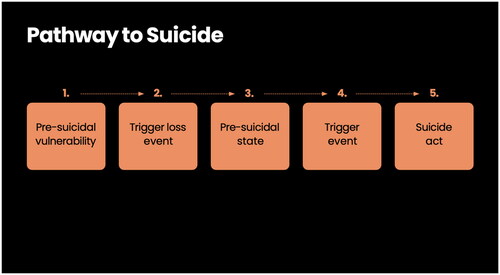

The pathway leading to death by suicide ()

Understanding emotional pain

Before discussing the pathway to suicide we need to examine the nature of emotional* pain and why suicide may be perceived as a necessary escape. From our first moments outside the womb until our last breath, life hurts. The profound pain of existence becomes apparent when we observe infants, who express their distress with every fibre of their physical being. As we age and our psychic apparatus matures, we learn how to transform the emotional pain from our physical bodies (soma) to representations of feelings* in our minds (psyche) (Van der Kolk, Citation1994).

The first indication that we are experiencing a feeling is a series of embodied sensations, which can be intensely painful and alarming. Gradually we learn to recognise the unique set of physical responses that accompany each emotional state. For example, fear or anxiety may be signalled by a rapidly beating heart, a tight chest, nausea and dizziness. Sadness, on the other hand, may be experienced as heaviness in the limbs, a sting in the throat, and watery or sore eyes. Once these patterns of sensations are recognised, we can symbolically* create a mental representation, and find images and words that allow psychic containment* and transformation. This process is cathartic, draining the physical pain from the body and allowing us to store these experiences in memory, place them in context within time and space, talk about them, and ultimately use them to develop and enrich our internal world.

Stage 1: Pre-suicidal vulnerability – a difficulty in symbolisation of emotional states. Resulting in a profound spit* in the ego*

Clinical work with suicidal patients reveals case after case in which the patient has never been able to achieve comfortable self-integration, but suffers continually a kind of divided inner life, in which the weak and helpless patient feels himself to be under the constant contemptuous scrutiny of an alien yet inner presence. This relentless scorn and the efforts to resist it are exhausting. At times this presence may become sufficiently contemptuous of the self so as to demand an execution, and the spent self may hopelessly acquiesce

Maltzberger and Buie (1980)

Individuals who eventually die by suicide view it as a solution because they are overwhelmed by physically and psychologically painful emotions that cannot be processed and transformed into feelings through symbolisation. This inability may stem from genetic or temperamental factors, a lack of supportive nurturing in the developmental environment, or encountering a loss that is too profound to process (Gibbons, Citation2024; Levi, Citation2008). Such difficulties may explain the greater risk of suicide among individuals on the autistic spectrum (Cassidy & Rodgers, Citation2017), and why men, who culturally are often encouraged to suppress their feelings from an early age, are 3-4 times more likely to die by suicide than women (NCISH, Citation2023).

This difficulty in symbolising emotions leads to incapacities in mourning and processing grief, which in turn impacts on the ability to navigate separation and individuation. Instead of cultivating a rich internal world through the effective processing of loss, the inner landscape remains barren and underdeveloped (Gibbons, Citation2024). This terrain is inhabited by primitive, unintegrated, and divided, ‘split’ aspects of the self. One part is detached, ruthless, and identifying with a powerful, primitive, vengeful, God-like superego*. Meanwhile the other aspect becomes diminished, defined by vulnerability, and projected onto the body. In this way the vulnerable part can be considered as separate and identified by the superego part as ‘bad’ and the cause of the current pain (Freud, Citation1917). The ‘victim’ body can be offered up as a sacrifice to this persecuting and vengeful ‘perpetrator’ superego (Campbell & Hale, Citation2017).

Experiencing some degree of splitting is normal. This phenomenon allows us to activate and utilise different facets of ourselves as various situations demand. For instance, as a doctor, I navigate between my ‘clinical’ self and my ‘patient’ self. When I’m not working, I connect with the more vulnerable ‘patient’ part of myself; however, when I’m functioning in my ‘clinical’ role, that part might become entirely inaccessible and I might not even recall its existence.

True ambivalence of suicide

It is this split in the ego that results in the true ambivalence* of suicide. It is as though there are two different personalities psychically housed in one body. One wants to die, one wants to live. One loves life, one hates life. One is planning the murder (the perpetrator), one knows nothing about it (the victim). This ambivalence is illustrated by the suicide note above. This split functioning can be hard to comprehend and can make the behaviour of those who are in a highly suicidal state bewildering. It is often very unclear which side of the personality you are talking to at any time. To understand this is key to understanding the risks inherent in the suicidal state (Ashe, 1980; Campbell & Hale, Citation2017; Maltzberger & Buie, 1980; Tillman, Citation2018).

Case example: The psychiatric liaison team referred Ms C, a barrister, to the Home Treatment Team (HTT) after assessing her following a serious suicidal act during an Easter break from work. Known for her compulsive work habits, Ms C was regarded by her colleagues as exceptionally dedicated and responsible. At the meeting she was highly distressed, said she was overwhelmed by terror and expressed a profound fear of her suicidality. The Home Treatment Team met with her once she was back at work the following week. She reassured them that she did not understand the concerns, saw no need for engagement with their services, and insisted she was ‘absolutely fine’. The HTT team remained worried but felt powerless to intervene. Tragically, Ms. C died by suicide the following weekend when she was not working.

During the organisation’s internal inquiry, the HTT faced criticism; they were told that they should have been aware of the risks due to the previous attempt. The inquiry team expressed disbelief at the HTT’s feedback that Ms. C had been very clear and reassuring in her interactions with them

Both teams had authentic engagements with different parts of Ms. C’s divided self. The Liaison team met with her when she was not working, where she revealed her vulnerable, ‘victim’, side that recognised she was at risk. Conversely, when she returned to work, the ‘perpetrator’ side became predominant, characterised by detachment, impenetrability, and dissociation, and this was the aspect that the HTT encountered. This can leave those left behind with feelings of having missed something or not having been vigilant enough. However, the truth is that they were genuinely engaged with one of the different sides of the individual and kept unaware of the other’s existence.

. I don’t seem to feel as though I want to die. It’s like another person telling me what to do. I feel as though my mind isn’t connected to my body, and it seems to refer to me as ‘you’, as in ‘Die, you fool, die’. I feel as though there are two of me, and the killer is winning.

Maltzberger and Buie (1980)

The split in the ego also sheds light on behaviours that are profoundly disturbing in individuals before they die by suicide, including how plans can be concealed and loved ones misled. This dynamic is highlighted in work by Tillman (Citation2022), who conducted interviews with those surviving suicide attempts of high lethality. Several interviewees spoke from their detached destructive ‘perpetrator’ aspect, describing deriving satisfaction from outsmarting parents, spouses, and therapists. They spoke candidly about their intent and ability to deceive those who were committed to helping them stay alive.

Stage 2: Trigger-first loss event and entry into the pre-suicidal state

When my death comes, it won’t be suicide. It’s that someone has murdered me. … I took those pills before, it was to kill the other part of me, but I really won’t die, I’ll just wake up and things will be different.

Maltzberger and Buie (1980, 147–157)

The division within the ego can go undetected for a considerable period of an individual’s life, acting as a dormant fault line. They can seem to function well until they face a major loss event in later life that requires mourning. Research corroborates this stage in the pathway, highlighting the significant loss events that often precede a death by suicide. These include: serious physical illness, bereavement (especially bereavement by suicide), relationship breakdown, being charged by the police (particularly for child sex offenses) and experiencing domestic violence (whether as perpetrator or victim) (Kafka et al., Citation2022; Rodway et al., Citation2020; Walter & Pridmore, Citation2012). These losses can occur weeks, months, or even years before the individual’s death. Following such loss, the resultant intense physical and emotional pain cannot be alleviated and becomes trapped within the body, exacerbating and widening the division within the psyche. The detached, destructive ‘perpetrator’ superego gains momentum and strength and starts to plan the vulnerable ‘victim’s’ downfall. In this context, eliminating the source of pain is perceived as the only avenue for relief (Freud, Citation1917). This scenario then evolves into the pre-suicidal state.

Stage 3: The pre-suicidal state: the suicidal fantasy

(The) intention is to preserve the essence of oneself for a better life beyond the magical passage of death.

Maltzberger and Buie (1980)

The Presuicidal State is a ‘quasi-delusional psychic retreat’ from intolerable anxiety. This means a transitory breakdown in reality which serves to detach the individual from the unbearable pain. In this retreat suicidal fantasies start to dominate mental life, where death is perceived as the solution to the problem. At no point does the individual truly believe that their existence will end following their planned death. Instead there is a conviction that a ‘survival self’ will continue life in a pain-free ‘bodiless way’ (Campbell & Hale, Citation2017; Maltzberger & Buie, 1980).

Many individuals who enter the pre-suicidal state do not proceed to die by suicide. For many it functions as a ‘transitional’ state that offers protection and some degree of affect regulation (Kleiman et al., Citation2018; Maltsberger et al., Citation2010; Schechter, 2022). The contemplation of suicide functions as an imagined psychological escape, if all else fails, a tactic that can soothe internal distress and prevent escalation.

The thought of suicide is a powerful comfort: it helps one through many a dreadful night

Nietzsche (Citation1886)

For some however, suicidal fantasy serves as the pivotal force that enables and propels the ‘act’.

These suicidal fantasies can be divided into six different categories.

Merging

This foundational fantasy underlies all others. It envisions death as a return to nature, merging with the universe to achieve a state of nothingness. It is seen as a passport to a new world, a blissful, dreamless, eternal sleep, or a permanent state of peace (Campbell & Hale, Citation2017; Maltzburger & Buie, 1980). Death is perceived as providing resolution, an opportunity for a fresh start, rebirth, and reunion with lost loved ones.

Revenge

…Would-be suicides often daydream of the guilt and sorrow of others gathered about the coffin, an imaginary spectacle which provides much satisfaction. …. he will be present as an unseen observer to enjoy the anguish of those who view his dead body

Maltzburger and Buie (1980)

With this suicidal fantasy, the individual aims to avenge a betrayal and imagines that they will witness the aftermath of this retribution.

Case example: Mr M in his suicide note wrote ‘You will never forget me now….’

An underlying issue with this fantasy is its potential effectiveness. It is not uncommon for individuals to face posthumous societally-sanctioned punishment for perceived poor treatment of the person who died.

A senior council officer (W) who took his own life was under ‘intense pressure’ as his local authority made budget cuts, an inquest has heard.

In his suicide note W wrote: ‘Dear A, I just wanted you to know that my death is not in any way or sense directed at you personally or meant as a comment on your leadership …’

…His suicide sparked an independent investigation into the alleged ‘domineering’ management style of the council’s chief executive, A. A, has since been cleared of any blame but left the council by mutual consent.

The Guardian (Citation2011)

Self-punishment

…he saw that he was condemned, repented himself, and brought again the thirty pieces of silver to the chief priests and elders, saying, I have sinned in that I have betrayed the innocent blood. …And he cast down the pieces of silver in the temple, and departed, and went and hanged himself.

The death of Judas: The Holy Bible (Testament 2018)

This fantasy is marked by a masochistic form of self-punishment, dominated by feelings of guilt and shame (Campbell & Hale, Citation2017). In some cases, this self-punishment may become eroticised. There are individuals who derive satisfaction from pain, suffering, and helplessness, creating elaborate sexual rituals leading up to their death (Maltzberger & Buie, 1980)

Assassination

Case example: Professor L was found deceased at home. He had just received a diagnosis of dementia. It was clear that he had planned to take his life if this circumstance arose, for many years.

In this fantasy, the body is assassinated to eliminate feelings of vulnerability and uncertainty. Paradoxically, suicide in this context can act as a form of self-protection, often aimed at avoiding future helplessness, disgrace, and preserving a sense of honour (Maltsberger, Citation1997; Ronningstam et al., Citation2020). Those who undertake significant journeys to facilities like Dignitas can, at times, be seen to fit this category.

Dicing with death

It becomes clear that eventually fate will be forced to embrace his victim and accept the executioner’s role

Asch, Citation1980

The quintessential example of this fantasy is Russian roulette. In this scenario, fate becomes the deciding partner, determining whether the individual lives or dies. Healthcare teams frequently find themselves in such a precarious situation, cautious about shifting their focus away from an individual. They often believe that their vigilant observation has narrowly prevented the person’s death on multiple occasions. A dangerous dynamic emerges, burdening those who fail to keep constant watch with feelings of having assumed the role of executioner.

This fantasy is also evident and societally endorsed in dangerous sports. The death of Marc-André LeClerc, a climber featured in the film ‘The Alpinist’, seems to exemplify this fantasy. He passed away at the age of 25, disappearing on a hazardous climb. He was renowned and lauded for his solo climbs of numerous mountains across various regions of the world. His choice of increasingly perilous routes hinted at an almost inevitable outcome.

Attempt at separation

In this fantasy suicide is seen as a final, desperate attempt to address unresolved separation issues. Tillman (Citation2022) noted several young adults facing difficulties in leaving home to attend college or start a new job spoke of suicide as a solution to their struggles with separation.

Case example: Mr. D was 40 years old and had been struggling with depression for 20 years since dropping out of university and returning home. He attempted to move out and live in supported accommodation, but this arrangement proved unsustainable for him, and he returned to live with his parents. Ultimately, he jumped from a bridge, wearing a backpack filled with bricks from his parents’ house.

All these fantasies can be reflected in the symbolic nature of the act of suicide itself (Campbell & Hale, Citation2017). For example, individuals travel from all over the world choosing to end their lives at places like the Golden Gate Bridge in America or Beachy Head in the UK. These locations are selected in the belief that they represent a portal or ‘Golden Gate’ to a pain-free, heavenly existence where they can start their lives over.

Stage 4: Second loss event-the final trigger

What sets off the crisis is almost always unverifiable. Newspapers often speak of ‘personal sorrows’ or of ‘incurable illness’. These explanations are plausible. But one would have to know whether a friend of the desperate man had not that very day addressed him indifferently. He is the guilty one. For that is enough to precipitate all the rancour’s and all the boredom still in suspension.

Camus (Citation1942)

For individuals who enter the pre-suicidal state and ultimately die by suicide, a final trigger is awaited. This event may appear minor or insignificant but is perceived by the individual as ‘penetrating proof of lack of care and functions as permission to act’ (Campbell & Hale, Citation2017; Tillman, Citation2022).

An eloquent account of this process has been described by Kevin, a young man, and one of the very few people to survive jumping from the Golden Gate Bridge. On this evening of his attempt he met a passer-by on the bridge.

A woman from my left approached me and pulled out a camera. She asked me to take her picture. She posed I took her picture quite a few times and then she walked away. That is when I said absolutely nobody cares. A voice in my head said, ‘jump now’ and I did.

Kevin- (BBC, Horizon Stopping Male Suicide, 2018)

Upon reviewing coroners’ records, distinct examples of final trigger events were identified. These loss events, which can be seen to be normal part of life, would be impossible avoid. They included: warnings of eviction, demands for rent, or being pursued for debt repayment. Career setbacks such as rejection after an interview, a reprimand at work, receiving exam results, and letters from solicitors. Relationship difficulties also played a significant role, including arguments or being informed that a romantic relationship was ending. Disputes with friends and family, and minor legal interactions with the police, like parking tickets and other minor offenses. There were also everyday frustrations, such as losing a wallet or a phone, and issues with renewing a passport.

Stage 5: Confusion and dissociation

The experience of betrayal and disappointment following the ‘Second Loss Event’ acts as the ‘straw that breaks the camel’s back’, creating conditions conducive to the enactment of suicide.

This stage is characterised by dissociation or a severance from the life-affirming aspects of the self. It is thought that when the individual has made a definitive decision, they cut all connections with others, both internally and externally, and a period of perceived calm ensues (Laufer & Laufer, Citation1984; Tahka, Citation1978; Tillman, Citation2022). This disengagement can be amplified by the use of alcohol, which further lowers inhibitions. The dissociation continues until the point of no return is reached when tragically, it may resolve.

When my hand left the handrail I suddenly realised that everything in my life was fixable apart from the fact I had jumped.

Ken Baldwin (New Yorker, 2003)

The legacy of suicide for those bereaved

Suicide freezes the relationship in the zenith of its sadism.

Campbell and Hale (Citation2017)

Campbell, Hale, and Maltsberger describe suicide as an ‘acting out’ behaviour intended to rid the self of pain (Campbell and Hale 201; Maltsberger & Buie, Citation1980). This ‘acting out’ functions as an unconscious defence mechanism, substituting actions for feelings. Through this behaviour, painful aspects of the deceased’s internal world are projected* into those left behind. In this way others are implicates in this enactment (Gibbons, Citation2023; Citation2024). Those drawn in may simply be bystanders, involved because the deaths occur in a public space, or they may be deliberately chosen and compelled to fulfil roles from the patient’s past, re-enacted in the present (Campbell & Hale, Citation2017; Ogden, Citation1984). Certain roles recur frequently, such as the careless mother, absent father, and the executioner (Ashe, 1980; Campbell & Hale, Citation2017).

Case example: As a train driver rounded a corner, he was confronted with the sight of someone on the tracks ahead, arms outstretched and eyes locked onto his. The driver was profoundly affected, expressing feelings of personal responsibility for the man’s death. This was the second such incident he had experienced. Unable to continue working, he retired due to mental health issues.

In this instance, the role of the executioner was projected into the train driver through gaze before death. This projective process left the driver burdened with feelings of responsibility that transcended reality.

The difference between suicide and assisted dying

However, closer scrutiny of unconscious processes reveals the less acceptable face of suicide as an act aimed at destroying the self’s body and tormenting the mind of another.

Campbell and Hale (Citation2017)

If suicide is an ‘acting out’ event then it is, in part, unconsciously designed to project into those bereaved, leaving unbearably painful posthumous messages. This dynamic is absent in assisted dying. In this author’s opinion, if the death induces feelings of guilt, blame, and culpability it can be classified as suicide. Conversely, if the bereaved are free from these painful projections, allowing them to experience uncomplicated grief and the liberty to mourn, then the death should not be classified in this way.

Conclusion

Our data show that there is not one factor that accounts for the suicidal impulse and action. Depression, psychic pain, impulsiveness, anger, anxiety, despair, loneliness, panic, violence, revenge, and a host of other factors are acting in a complex and almost infinite combination to produce the catastrophic behavior in each participant.

Tillman (Citation2018)

This exploration of the pathway to suicide reveals it often stems from a response to loss and an incapacity to mourn, indeed suicidal thoughts are a natural part of the mourning process (Gibbons, Citation2024). This suggests that it could affect anyone; it is likely we can all conceive of losses that would seem insurmountable, potentially making suicide appear as a viable option.

Suicide exposes the fundamental conflict at the heart of life, between the drive to live and to die, and the potent destructive forces intrinsic to human nature. It confronts us with the reality that we are all both victims and perpetrators and the potential for suicide lies within us all. This suggests that ‘risk’ is an integral part of the human condition. Within mental health services, there’s a repeated refrain that we need ‘to keep people safe’, as though this is a feasible target. If the capacity for destruction is inherent within us all as part of our human nature, then the concept of complete safety is unachievable.

Rather than focusing solely on reducing rates without grasping the underlying causes, perhaps we could seek to understand, and open our hearts to both the perpetrator and the victim in ourselves and others. Is our reluctance to address the true roots of suicide a result of its deep personal relevance. Do we fear touching upon a collective unconscious understanding of the motivations behind it? By attributing it to systemic ‘failures’ or blaming ourselves or others, we contribute to the fantasy that we understand the nature of the beast (Gibbons, Citation2024). In doing so, we distance ourselves and create a protective barrier between the pain of those bereaved, and our own concerns for ourselves and our loved ones. Do we fear suicide as a siren’s song, that to look too intently would risk drawing us too close to the edge?

Acknowledgements

I’d like to thank Rob Hale and Don Campbell for their dedicated work over the years. Particularly, I want to express gratitude to Rob for generously dedicating his time and nurturing a benign curiosity about the nature of suicide.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/bjpsych-bulletin/article/someone-is-to-blame-the-impact-of-suicide-on-the-mind-of-the-bereaved-including-clinicians/EFFE8127E4FDDE3A2AF65D3FF542FD02

References

- Asch, S. (1980). Suicide, and the hidden executioner. International Review of Psychoanalysis, 7, 51–60.

- BBC. (2018). https://www.bbc.co.uk/iplayer/episode/b0bgv82g/horizon-2018-6-stopping-male-suicide

- Campbell, D., & Hale, R. (2017). Working in the dark: Understanding the pre-suicide state of mind. Routledge.

- Camus, A. (1942). The Myth of Sisyphus. Kindle Edition. Penguin Books Ltd.

- Cassidy, S., & Rodgers, J. (2017). Understanding and prevention of suicide in autism. The Lancet. Psychiatry, 4(6), e11. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(17)30162-1

- Critchley, S. (2015). Notes on suicide. Fitzcarraldo Editions.

- Freud, S. (1917). Mourning and Melancholia. The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, 14(1914–1916), 237–258.

- Gibbons, R. (2023). Eight ‘truths’ about suicide. BJPsych Bulletin, 2023, 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjb.2023.75

- Gibbons, R. (2024). The mourning process and its importance in mental illness: A psychoanalytic understanding of psychiatric diagnosis and classification. BJPsych Advances, 30(2), 80–88. https://doi.org/10.1192/bja.2023.8

- Jung, C. G. (1953). Collected works, Vol. 12. Psychology and Alchemy.

- Kafka, J. M., Moracco, K. B. E., Taheri, C., Young, B. R., Graham, L. M., Macy, R. J., & Proescholdbell, S. (2022). Intimate partner violence victimization and perpetration as precursors to suicide. SSM – Population Health, 18, 101079. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2022.101079

- Kleiman, E. M., Coppersmith, D. D., Millner, A. J., Franz, P. J., Fox, K. R., & Nock, M. K. (2018). Are suicidal thoughts reinforcing? A preliminary real-time monitoring study on the potential affect regulation function of suicidal thinking. Journal of Affective Disorders, 232, 122–126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2018.02.033

- Laufer & Laufer. (1984). Adolescence and developmental breakdown, New Haven and London. Yale University Press.

- Levi, Y., Horesh, N., Fischel, T., Treves, I., Or, E., & Apter, A. (2008). Mental pain and its communication in medically serious suicide attempts: An “impossible situation”. Journal of Affective Disorders, 111(2-3), 244–250. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2008.02.022

- Maltsberger, J. T. (1997). Ecstatic suicide. Archives of Suicide Research, 3(4), 283–301. https://doi.org/10.1080/13811119708258280

- Maltsberger, J. T., & Buie, D. H. (1980). The devices of suicide: Revenge, riddance, and rebirth. International Review of Psycho-Analysis, 20, 397–408.

- Maltsberger, J. T., Ronningstam, E., Weinberg, I., Schechter, M., & Goldblatt, M. J. (2010). Suicide fantasy as a life-sustaining recourse. The Journal of the American Academy of Psychoanalysis and Dynamic Psychiatry, 38(4), 611–623. https://doi.org/10.1521/jaap.2010.38.4.611

- NCISH. (2023). https://sites.manchester.ac.uk/ncish/reports/annual-report-2023/

- New Yorker. (2003). Letter from California October 13, 2003. Issue Jumpers.

- Nietzsche, F. (1886). The Essential Nietzsche: Beyond Good and Evil and The Genealogy of Morals. Chartwell Books.

- Ogden, T. H. (1984). Instinct, phantasy, and psychological deep structure: A reinterpretation of aspects of the work of Melanie Klein. Contemporary Psychoanalysis, 20(4), 500–525. https://doi.org/10.1080/00107530.1984.10745750

- Ons. (2023). https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/deaths/bulletins/quarterlysuicidedeathregistrationsinengland/2001to2022registrationsandquarter1jantomartoquarter3julytosept2023provisionaldata

- Pitman, A., Osborn, D., King, M., & Erlangsen, A. (2014). Effects of suicide bereavement on mental health and suicide risk. The Lancet. Psychiatry, 1(1), 86–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(14)70224-X

- Rodway, C., Tham, S., Ibrahim, S., Turnbull, P., Kapur, N., & Appleby, L. (2020). Children and young people who die by suicide: Childhood-related antecedents, gender differences and service contact. BJPsych Open, 6(3), E49. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2020.33

- Ronningstam, E., Weinberg, I., & Maltsberger, J. T. (2020). Psychoanalytic theories of suicide. Oxford Textbook of Suicidology and Suicide Prevention. p. 147.

- Schechter, M., Goldblatt, M. J., Ronningstam, E., & Herbstman, B. (2022). The psychoanalytic study of suicide, part I: An integration of contemporary theory and research. Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association, 70(1), 103–137. https://doi.org/10.1177/00030651221086622

- Tahka, V. A. (1978). On some narcissistic aspect of self-destructive behaviour and their influence on its predictability. Psychopathology of Direct and Indirect Self Destruction, Psyciatra Fennica, Supplementum. 59–62.

- Testament, O. (2018). The holy bible.

- The Guardian. (2011). https://www.theguardian.com/society/2011/aug/31/inquest-suffolk-pressure-suicide-white

- Tillman, J. G. (2018). Disillusionment and suicidality: When a developmental necessity becomes a clinical challenge. Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association, 66(2), 225–242. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003065118766013

- Tillman, J. G., Stevens, J. L., & Lewis, K. C. (2022). States of mind preceding a near-lethal suicide attempt: A mixed methods study. Psychoanalytic Psychology, 39(2), 154–164. https://doi.org/10.1037/pap0000378

- Van der Kolk, B. A. (1994). The body keeps the score: Memory and the evolving psychobiology of posttraumatic stress. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 1(5), 253–265. https://doi.org/10.3109/10673229409017088

- Walter, G., & Pridmore, S. (2012). Suicide and the publicly exposed pedophile. The Malaysian Journal of Medical Sciences, 19(4), 50.