ABSTRACT

The authors present an analytical model to distinguish between different aspects and modes of innovation. By showing how innovation in the public sector differs from the private sector, this paper is an important stepping-stone to understanding and supporting innovation in the public sector.

Innovation has been long studied in the private services sector, and even longer in the private manufacturing sector, but the study of innovation in the public sector is a comparably new topic and is usually omitted from studies of innovation in general (Djellal, Gallouj, & Miles, Citation2013; Gallouj & Zanfei, Citation2013; Potts & Kastelle, Citation2010). However, the research field of innovation in the public sector, also discussed under different labels such as ‘public sector innovation’, ‘public service innovation’ and ‘social innovation’, is growing.

The EU projects PUBLIN (Windrum & Koch, Citation2008), MEPIN (Bloch, Citation2011) and LIPSE (De Vries, Bekkers, & Tummers, Citation2016; Voorberg, Bekkers, & Tummers, Citation2014) have been influential in forming and defining the field, as have journal articles and journal special issues. Research is ongoing in different academic fields, particularly in public administration (Albury, Citation2005; Bartlett & Dibben, Citation2002; Borins, Citation2001; Golden, Citation1990; Hartley, Citation2005; Moore & Hartley, Citation2008; Mulgan, Citation2007; Osborne & Brown, Citation2013) and innovation studies (Djellal et al., Citation2013; Gallouj & Zanfei, Citation2013; Potts & Kastelle, Citation2010).

At this stage, it is difficult to get an overview of the field but some central themes in the study of innovation in the public sector include barriers, drivers and conditions for innovation (for example Bekkers, Tummers, & Voorberg, Citation2013; Bloch, Citation2011; Demircioglu & Audretsch, Citation2017; Potts & Kastelle, Citation2010). Voorberg et al. (Citation2014) notice that this is a dominant theme in the study of innovation in the public sector, in particular on co-production: ‘most studies focused on the identification of influential factors, while hardly any attention is paid to the outcomes’ (Voorberg et al., Citation2014, p. 1). Another common theme is the measurement of innovation in the public sector (Arundel & Huber, Citation2013; Bloch & Bugge, Citation2013; Kattel et al., Citation2013). Yet another common theme is what is typical of public sector innovation and what distinguishes it from innovation in the private sector (De Vries et al., Citation2016; Halvorsen, Hauknes, Miles, & Røste, Citation2005; Nählinder, Citation2013) or the service sector (Djellal et al., Citation2013). Other, overlapping, themes are open innovation (Fuglsang, Citation2008) and social innovation (Bekkers et al., Citation2013).

Previous research has shown that research on innovation in the public sector is scattered and tends to be non-theoretical (De Vries et al., Citation2016). Kattel et al. (Citation2013) discuss how, using the term ‘public sector innovation’, there is a large discrepancy in defining the core concept. De Vries et al. (Citation2016) noted that the term ‘innovation’ is sometimes used to describe different but related phenomena. For example, in three papers with a clear focus on the public sector as an innovator in its own right, Savory (Citation2009), Salge (Citation2012) and Kallio, Lappalainen, and Tammela (Citation2013) all discuss innovation, but from different perspectives, and each paper uses a different terminology. Innovation is, for example, discussed as ‘innovation modes’ (Salge, Citation2012), ‘innovation targets’ (Kallio et al., Citation2013) or ‘practice-based and research-based innovations’ (Savory, Citation2009). Innovation processes are described as ‘knowledge production processes’ (Savory, Citation2009) or ‘innovative’ searches (Salge, Citation2012). In addition, the three papers all discuss how innovation in public sector may be supported, but they do this using different terminologies; they refer to different authors; and they use different bodies of knowledge.

This lack of conceptual congruity complicates the building of a theoretical foundation for the study of public sector innovation. Distinguishing clearly between different aspects of innovation clarifies existing knowledge. The research field would benefit from a stronger theoretical base, and more coherence in research and terminology.

We have found that, in using the term ‘innovation’, reference is often made to innovation as a new product, process or organizational change (innovation as outcome). Sometimes reference is made to the process of turning an idea into an innovation (innovation process) and sometimes to the support provided to facilitate such a process (innovation support). Analytically distinguishing between these three interrelated innovation aspects would help to clarify and disentangle the contribution of previous research and provide a basis for describing and analysing innovation in the public sector.

This paper describes the development and testing of an analytical model that distinguishes between different aspects and modes of innovation. We then discuss how this analytical model furthers our understanding of how innovation in public sector differs from innovation in private sector.

Theoretical background

In order to improve our understanding of how public sector innovation differs from innovation in the private sector, we need a theoretical background for our analytical model. This background comprises two themes: a conceptual translation of the innovation concept for the purposes of studying innovation in the public sector, and different modes of innovation.

Double translation

The understanding of innovation in the public sector has developed in tandem with the understanding of innovation in the private sector, in particular the manufacturing sector. The study of innovation in public sector has been heavily influenced by innovation in the private sector. There has been discussion about how innovation in public sector should be related to innovation in manufacturing and innovation in services (Bloch & Bugge, Citation2013; Djellal et al., Citation2013; Nählinder, Citation2013; Osborne & Brown, Citation2013). Sometimes researchers have regarded innovation in the public sector merely as a special case of private sector innovation. In so doing, innovation in the public sector can never differ qualitatively from innovation in the private sector.

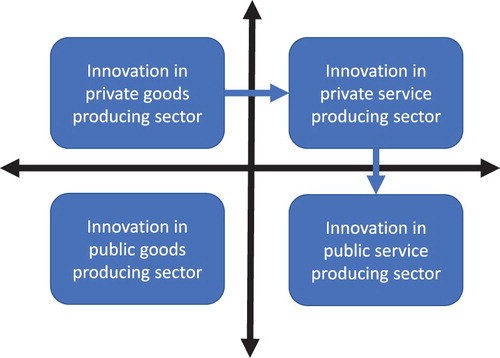

The influence of research on the manufacturing sector on the research on innovation in the public sector has provided a basis upon which to study innovation in the public sector, but it has also produced a biased, normative view of the concept of innovation (Alsos, Ljunggren, & Hytti, Citation2013; Fogelberg Eriksson, Citation2014; Hobday, Citation2005; Wegener & Tanggaard, Citation2013). Therefore, in order to study innovation in the public sector, we need to make two conceptual translations of the innovation concept: the first translation is from innovation in producing goods to innovation in delivering services a shift which has given rise to a considerable academic discussion (Miles, Citation2005; Carlberg, Kindström, & Kowalkowski, Citation2014). The second translation of the innovation concept from the enterprise, market or private sphere to the government or public sphere is more problematic, although though some researchers do not consider it a problem (Djellal et al., Citation2013).

Innovativeness in the public sector may differ from innovativeness in the private sector. The problem, articulated by the concepts ‘assimilist’, ‘demarcation’, ‘inversion’ and ‘synthesis’ (Coombs & Miles, Citation1999; Djellal et al., Citation2013; Droege, Hildebrand, & Heras Forcada, Citation2009) is how to reap the benefits of research on innovation in manufacturing and innovation in services (assimiliation), while at the same time being open to sector-specific characteristics (synthesis approach). A first problem is identifying how innovation in the public sector differs from innovation in the private sector. This is difficult because the public sector is extremely heterogeneous: it is hard to find the ‘public’ in the public sector. For example, healthcare is sometimes organized as a public sector industry, sometimes as a private sector industry and often as a combination of the two. Studies of innovation in healthcare do not always discuss the degree to which findings apply to the whole healthcare sector or the public or private part of it.

One important difference between the public and the private sectors, however, is that the public sector is steered by principles that do not apply in the private sector. This impacts innovation. Petersson and Söderlind (Citation1993) argue that the public sector typically can be described as based on three principles democracy, ‘rechtsstaat’ and the welfare state and that these principles conflict. The principle of democracy is that a public sector organization should ultimately be steered by politicians who have been elected by citizens. The principle of rechtsstaat is about rights and the limitation of a government’s power by law and includes the principle of equal treatment. The principle of the welfare state stands for the provision (and production) of welfare to the citizens and stresses the importance of the efficient production and delivery of services. The private sector is not subject to the principle of democracy, nor by the principle of rechtsstaat. The only principle applying to both sectors is the efficiency inherent in the welfare state. Value creation thus takes different forms in the public sector than in the private sector, which likely also concerns innovativeness (Nählinder, Citation2013). Hence the double translation explained in .

Figure 1. The double translation of the innovation concept (Nählinder & Fogelberg Eriksson, Citation2017).

Innovation modes: not all innovations are STI (science and technology based)

A widespread misunderstanding of innovation is that it is based on R&D, it is tangible and highly visible. However, this does not apply to all innovations. In 2007, Jensen et al., building on Lundvall and Johnson (Citation1994), developed a distinction between two different types of innovation modes. They labelled these ‘STI’ (science and technology based) and ‘DUI’ (doing, using, interacting). These labels may be used to broaden and qualify the understanding of innovation and innovative differences between the private and the public sectors.

The twin concepts of STI and DUI put important differences into words see . STI needs considerably more explicit support (which is also, possibly, why this support typically is so well developed). Innovations which are based on DUI processes are difficult to count, support and diffuse. The dilemma of DUI is that they tend to be spontaneous and ubiquitous, but difficult to encourage. Comparing STI and DUI makes it clear that they have very different properties: something we elaborated upon in our analytical model.

Table 1. A comparison of STI and DUI (Nählinder and Fogelberg Eriksson, 2017).

Developing the analytical model

Thus far, it is clear that:

Innovation has three aspects (outcome, process and support).

There are differences in innovativeness according to the sector (goods producing sector/services producing sector).

Institutional context (public sector/private sector) matters.

The public sector is guided by different principles (rechtstaat, democracy and welfare state).

Innovations may be divided in different innovation modes (STI/DUI).

The model in shows that the three aspects of innovation should ideally be aligned to create favourable conditions for innovation: innovation cannot be expected to be an outcome if the innovation process is not supported accordingly. Support designed for STI processes may fail to support, and even discourage, DUI processes. This implies that the notion of a ‘trickle-down effect’ (if a system is designed for big innovations, small innovations will automatically follow) has important flaws. It also implies that suitable support for DUI processes must be developed and readily available.

Table 2. Analytical model: aspects of innovation (outcome, process, support) in relation to modes of innovation (STI and DUI).

An analytical model is, by definition, a simplification and reduces complexity. It should be noted that our model is not intended as a prescriptive one, nor is it deterministic in the sense that one aspect cannot follow another even if not aligned. The model, rather, focuses on dimensions which may be of importance in order to understand innovativeness. In practice, innovation aspects and innovation modes may very well be intertwined with each other and with the institutional context. Many innovations have traits of both STI and DUI, i.e. should not be understood as a dichotomy where one excludes the other (Jensen, Johnson, Lorenz, & Lundvall, Citation2007).

Applying the analytical model: PIMM

Our analytical model was applied to a Swedish public health sector innovation project PIMM (product development in the care sector) (Nählinder, Citation2010). PIMM (2006–2010) was a joint regional innovation project including business support organizations (ALMI and HNV) and healthcare organizations (two municipalities and a regional health council). The purpose of the PIMM project was to increase innovation in healthcare organizations, in particular among nurses and assistant nurses. Therefore healthcare employees were the innovators, turning their ideas into innovations. The ideas were then to be out-sourced to firms, thus both creating increased innovativeness in the public sector and more regional jobs.

The backbone of PIMM was that it was co-ordinated and mostly executed by an experienced business support organization: ALMI. Innovation advisors from ALMI helped qualify the ideas, finance prototypes, file patents and scout for firms interested in licensing the products. In the last step of the PIMM model, the products would go to the market, where the regional health council and the municipalities were important potential customers.

Idea pilots (peers who held presentations, helped to scout for ideas and supported the idea carriers throughout the PIMM model) played an important role. The idea pilots gave examples of (mostly goods) innovations and encouraged their peers to recognize their own innovativeness. Initially the idea pilots were thought to engage only in the first phase of the innovation support, but were later acknowledged for their role also later on in the process.

Employees were encouraged to present ideas to their idea pilot, who then assisted them in developing their ideas. The ideas for innovations were to come from their working practice and the development and formalization of the ideas were made in their spare time. Only on a few occasions were idea carriers allowed to meet with the innovation pilot during working hours.

An analysis of the ideas supported by PIMM showed that, out of 306 ideas presented in November 2009, 21 ideas were service innovations, four ideas were innovations which combined goods and services and 275 were goods innovation ideas. The nature of the innovation was difficult to determine in six cases. None of the ideas were organizational innovation ideas (Nählinder, Citation2010).

The project ran into difficulties supporting organizational innovations (these ideas were not even registered). These were not at all compatible with the PIMM model which made them, in a way, easy to handle (exclude). The service innovations, on the other hand, were trickier. On one hand, they resembled goods innovations well enough to be tweaked into the system. On the other hand they had (at least) two properties which made them difficult to support in the PIMM model. First, a new service needed a customer in order to be developed, but the municipalities and the regional health council were not prepared to take on the role as customer. Second, the service innovations could not be separated from their idea carrier and out-sourced. PIMM presented organizational innovation and service innovation tips on their homepage to respond to the problem of how to handle ideas presented to PIMM which could not be supported by the PIMM model.

Analysing the case of PIMM

clarifies how PIMM simultaneously had traits of both STI and DUI. PIMM was primarily an innovation support project. It was based on previous innovation support in other industries which meant that it reproduced the stylized image of an innovation process. It has some resemblance to the linear model (Godin, Citation2006; Kline & Rosenberg, Citation1986), which was developed with STI processes in mind, including steps to design prototypes. It was thus not tailor-made to fit the innovation processes of the innovations of the target group (nurses and assistant nurses). The idea pilots smoothed the edges of the PIMM model and made it work for the idea carriers.

Table 3. PIMM summarized in the analytical model.

Although the PIMM project was very keen to support different types of innovations, they did not have the mechanisms to do so. Neither did they see what possible mechanisms could be used to support organizational and service innovations. Thus, the design of the PIMM model gave a clear message as to which innovations were desirable.

So it can be argued that the innovation support team favoured certain innovation processes over others (i.e. STI over DUI) and, in consequence, that they directed and even excluded possible innovations.

The PIMM model focused exclusively on innovation within the realm of the welfare state principle, to the degree that it is difficult to see traces of democracy and rechtstaat in the project. Although the specific industry context has relevance here (ideas for goods innovations are probably more frequent in healthcare than in, say, social services), so has the public sector as an institutional setting.

Discussion

Our analytical model meant that DUI could be separated from STI, which is crucial for understanding the aspects of innovation. STI and DUI processes give rise to different types of innovation and require different kinds of support. Institutional context was also shown to be of importance to innovation.

Returning to Petersson and Söderlind’s (Citation1993) three principles, we observed that:

The range of innovation as outcome can differ by sector. While innovation can take numerous forms in both the private and public sectors, innovation outcomes in democracy and rechtstaat are unique to the public sector. Examples of these are e-voting and law-making. More attention should be paid to identifying and measuring these innovations.

Innovation processes can differ between the private sector and the public sector. In the public sector, the three principles often interact and all three may have an impact on how innovations develop. For example, the Australian Department of Industry has an online feasibility test for innovations in the public sector. One of the questions (No. 9) asks the responder to estimate the importance of political support for an idea to be feasible. Another question (No. 14) regards the feasibility of the idea in relation to the budget cycle, planning cycle and election cycle. Both these examples show how the principle of democracy is of importance, not only the principle of a welfare state.

In contrast to the private sector, innovation support in the public sector needs to include the political level and public transparency.

Jensen et al. (Citation2007) developed and operationalized the concepts of STI and DUI within the framework of the private manufacturing sector. In order for the concepts to reach their full potential in public sector research, they too, must undergo the double translation.

STI may take different forms in the public sector as compared to the private sector. R&D is a fundamental in STI, but very scarce in both service sectors. The concept of STI must therefore undergo the double translation. For example, STI innovations associated with democracy or reechtstaat (the legislation process) may differ from these which are associated with welfare production. This is a simplified example, and will need further investigation.

Concerning DUI, we should expect to find both similarities and differences in innovation as outcome, innovation process and innovation support in the private and public sector. One reason why we might encounter similarities is that DUI occur at the workplace level where the institutional context is less important to the work process. However, in the public sector, the three principles can affect DUI at the workplace level. For example, two principles come to the fore when a school bureaucrat is expected to treat students equally and make decisions with legal certainty (rechtstaat) and, at the same time, to attract new students (welfare state). Having to navigate the two principles affects which innovations can be made (innovation as outcome) and how the innovations are made (innovation process).

Concluding remarks

The analytical model presented here was a useful tool for finding inconsistencies in, and distinguishing analytically between, innovation as outcome, innovation processes and innovation support. As a result, we were able to see how innovations were developed and how innovativeness was supported in the PIMM case.

The analytical model demonstrated how STI processes and DUI processes were connected to different kinds of innovation support and produced different outcomes. Drawing on the model, we can conclude that ‘trickling down’ will not work, i.e. innovation support aiming for STI innovation will not automatically lead to DUI innovation. The design of innovation support must take the differences between DUI and STI into consideration in order to be effective.

The analytical model raises new questions for further research in this area and stresses the importance of a double translation of STI and DUI. It raises questions about the impact of conceptualizations originally developed for the private sector and it highlights the need for the development of concepts specifically for innovation in the public sector.

The question about what differentiates innovation in the public sector from innovation in the private sector still remains. In fact, two questions need to be addressed:

What characterizes different STI and DUI processes in the public sector? Public sector STI and DUI processes need to be studied as innovation processes. It is also important to discuss how STI and DUI processes in the public sector are operationalized and measured.

How do STI and DUI processes in the public and private sector differ, and why? Are there specific conditions in the public sector that hinder or facilitate STI and DUI?

Finally, more studies are needed in different parts of the public sector. Since the public sector has to follow principles that are not used in the private sector, this should also be mirrored in their innovations something which needs to be empirically and theoretically grounded.

The analytical model presented provides a framework for simultaneously capturing different aspects and modes of innovation. Further, by introducing the three principles, it is very clear that innovation can be qualitatively different in the public and the private sectors. The differences between the public and the private sector are complex and cannot be analysed and understood in their entirety. However, by using the analytical distinctions developed and presented in this paper, the most important differences become clearer. Mainstream innovation research must be translated into the public context, otherwise innovation policy will be both ineffective and counter-productive.

Impact

For public sector innovation support to be effective, organizations must be aware of what types of innovation they want to support and the nature of the innovation processes. This paper provides a model which will help public sector organizations begin to do this.

Acknowledgement

This article was made possible through a grant from VINNOVA (No. 2014-00908): the Swedish National Innovation Agency.

Notes on contributors

Johanna Nählinder is a Senior Lecturer in the Division of Project Innovation and Entrepreneurship (PIE), Department of Management and Engineering, Linköping University, Sweden.

Anna Fogelberg Eriksson is a Senior Lecturer in the Department of Behavioural Sciences and Learning at Linköping University, Sweden.

References

- Albury, D. (2005). Fostering innovation in public services. Public Money & Management, 25(1), 51–56.

- Alsos, G., Ljunggren, E., & Hytti, U. (2013). Gender and innovation: State of the art and a research agenda. International Journal of Gender and Entrepreneurship, 5(3), 236–256.

- Arundel, A., & Huber, D. (2013). From too little to too much innovation? Issues in measuring innovation in the public sector. Structural Change and Economic Dynamics, 27, 146–159.

- Bartlett, D., & Dibben, P. (2002). Public sector innovation and entrepreneurship. Case studies from local government. Local Government Studies, 28, 107–121.

- Bekkers, V. J. J. M., Tummers, L. G., & Voorberg, W. H. (2013). From public innovation to social innovation in the public sector: A literature review of relevant drivers and barriers. Erasmus University Rotterdam.

- Bloch, C. (2011). Measuring public innovation in the nordic countries. Copenhagen manual. Nordiska ministerrådet.

- Bloch, C., & Bugge, M. (2013). Public sector innovation. From theory to measurement. Structural Change and Economic Dynamics, 27, 133–145.

- Borins, S. (2001). Encouraging innovation in the public sector. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 2, 310–319.

- Carlberg, P., Kindström, D., & Kowalkowski, C. (2014). The evolution of service innovation research. A critical review and synthesis. Service Industries Journal, 34(5), 373–398.

- Coombs, R., & Miles, I. (1999). Innovation, measurement and services. The new problematique. In J. S. Metcalfe, & I. Miles (Eds.), Innovation systems in the service economy. Measurement and case study analysis. Kluwer.

- Demircioglu, M. A., & Audretsch, D. B. (2017). Conditions for innovation in public sector organizations. Research Policy, 46, 1681–1691.

- De Vries, H., Bekkers, V., & Tummers, L. (2016). Innovation in the public sector: A systematic review and future research Agenda. Public Administration, 94, 145–166.

- Djellal, F., Gallouj, F., & Miles, I. (2013). Two decades of research on innovation in services. Which place for public services? Structural Change and Economic Dynamics, 27, 98–117.

- Droege, H., Hildebrand, D., & Heras Forcada, M. (2009). Innovation in services: present findings, and future pathways. Journal of Service Management, 20(2), 131–155.

- Ellström, P.-E. (2010). Practice-based innovation: a learning perspective. Journal of Workplace Learning, 22(1–2), 27–40.

- Evans, K., et al. (2015). Developing knowledgeable practice at work. In M. Elg (Ed.), (Eds), Sustainable development in organizations. Studies on innovative practices. Edward Elgar.

- Fogelberg Eriksson, A. (2014). A gender perspective as a trigger and facilitator of innovation. International Journal of Gender and Entrepreneurship, 6(2), 163–180.

- Fuglsang, L. (2008). Capturing the benefits of open innovation in public innovation: A case study. International Journal of Services Technology and Management, 9, 234–248.

- Fuller, A., Unwin, L., et al. (2004). Expansive learning environments: Integrating personal and organisational development. In H. Rainbaird (Ed.), Workplace Learning in Context. Routledge.

- Gallouj, F., & Zanfei, A. (2013). Innovation in public services. Filling a gap in the literature. Structural Change and Economic Dynamics, 27, 89–97.

- Godin, B. (2006). The linear model of innovation. An historical construction of an analytical framework. Science Technology & Human Values, 31(6), 639–667.

- Golden, O. (1990). Innovation in public sector human services programs: The implications of innovation by ‘groping along’. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 9, 219–248.

- Gustavsson, M. (2009). Facilitating expansive learning in a public sector organizations. Studies in Continuing Education, 31(3), 245–259.

- Halvorsen, T., Hauknes, J., Miles, I., & Røste, R. (2005). On the differences between public and private sector innovation. Publin Report D.

- Hartley, J. (2005). Innovation in governance and public services. Past and present. Public Money & Management, 25(1), 22–34.

- Hobday, M. (2005). Firm-level innovation models. Perspectives on research in developed and developing countries. Technology Analysis and Strategic Management, 17, 121–146.

- Høyrup, S. (2010). Employee-driven innovation and workplace learning. Basic concepts, approaches and themes. Transfer: European Review of Labour and Research, 16(2), 143–154.

- Jensen, M. B., Johnson, B., Lorenz, E., & Lundvall, B. A. (2007). Forms of knowledge and modes of innovation. Research Policy, 36(5), 680–693.

- Kallio, K., Lappalainen, I., & Tammela, K. (2013). Co-innovation in public services: Planning or experimenting with users? The Innovation Journal, 18(3).

- Kattel, R., Cepilovs, A., Drechsler, W., Kalvet, T., Lember, V., & Tõunurist, P. (2013). Can we measure public sector innovation? A literature review. Erasmus University Rotterdam.

- Kline, S. J., & Rosenberg, N. (1986). An overview of innovation. In R. Landau, & N. Rosenberg (Eds.), The positive sum strategy: Harnessing technology for economic growth. National Academy Press.

- Lundvall, B-Å, & Johnson, B. (1994). The learning economy. Journal of Industry Studies, 1, 23–42.

- Miles, I. (2005). Innovation in services. In J. Fagerberg, D. C. Mowery, & R. R. Nelson (Eds.), The oxford handbook of innovation. Oxford University Press.

- Moore, M., & Hartley, J. (2008). Innovations in governance. Public Management Review, 10, 3–20.

- Mulgan, G. (2007). Ready or not: Taking innovation in the public sector seriously. NESTA.

- Nählinder, J. (2010). Where are all the female innovators? Nurses as innovators in a public sector innovation project. Journal of Technology Management & Innovation, 5(1), 13–29.

- Nählinder, J. (2013). Understanding innovation in a municipal context. Innovation: Management, Policy and Practice, 15(3), 315–325.

- Nählinder, J., & Fogelberg Eriksson, A. (2017). The MIO model. A guide for innovation support in public sector organisations. Scandinavian Journal of Public Administration, 21(2), 23–47.

- Osborne, S. P., & Brown, K. (2013). Introduction: Innovation in services. In S. P. Osborne, & K. Brown (Eds.), Handbook of Innovation in Public Services. Edward Elgar.

- Petersson, O. and Söderlind, D. (1993), Förvaltningspolitik (Administrative Policy) (Publica).

- Potts, J., & Kastelle, T. (2010). Public sector innovation research: What is next? Innovation: Management, Policy and Practice, 12(2), 122–137.

- Salge, T. O. (2012). The temporal trajectories of innovative search. Insights from public hospital services. Research Policy, 41, 720–733.

- Savory, C. (2009). Building knowledge translation capability into public-sector innovation processes. Technology Analysis & Strategic Management, 21(2), 149–171.

- Voorberg, W. H., Bekkers, V. J. J. M., & Tummers, L. G. (2014). A systematic review of co-creation and co-production: Embarking on the social innovation journey. Public Management Review, 17(9), 1333–1357.

- Wegener, C., & Tanggaard, L. (2013). The concept of innovation as perceived by public sector frontline staff. Outline of a tripart empirical model of innovation. Studies in Continuing Education, 35(1), 81–101.

- Windrum, P., & Koch, P. (Eds.). (2008). Innovation in the public services. Entrepreneurship, creativity and management. Edward Elgar.