ABSTRACT

Mostly unknown to the general public, a fragmented landscape of transnational organizations has been developing in Europe. These organizations work across borders, but not entirely in the EU, and they generally have some basis in European law or policies. An inventory by the authors suggests there are at least 370 transnational organizations in Europe. Transnational organizations challenge basic notions of accountability: it is often very difficult to understand what the organization is doing, to whom it is accountable or even where it is located. This is not to say that accountability is necessarily a problem but much more research and insight is definitely required.

IMPACT

This article aims to put the almost 400 transnational organizations as a fragmented set of partially European organizations on the agenda. By understanding them as partially European (and partially regional, local or national), the authors raise issues of accountability and transparancy of those organizations. The article will be of value to European and regional policy-makers relating to various transnational organizations but also to leaders and staff in those organizations who need to relate (and account) to their important external stakeholders. These organizations offer opportunities for continued European collaboration after Brexit.

Uncharted European territory

The landscape of European public sector organizations has been changing significantly over the past few decades in more ways than is commonly acknowledged. The rise of fully-fledged international organizations (Koppell, Citation2010), the growth of European agencies (Egeberg & Trondal, Citation2011) and the accountability challenges following post-crisis reforms (Dawson, Citation2015) have all been noted in the recent academic literature. In all of these cases, scholars have claimed that the complexity of institutional settings, the distance to the electoral process and the inevitable policy struggle between national and international powers in multi-level systems of government (Hooghe, Marks, & Marks, Citation2001), may impair accountability.

However, more or less hidden from the public eye, another category of international organization has been developing in Europe: transnational European organizations (Joosen & Brandsma, Citation2017). Transnational organizations perform EU-funded or EU-regulated tasks and work across national borders but not in the entire EU and not necessarily only in the EU. Transnational organizations have been set up on a variety of legal bases, often under more than one jurisdiction, and come in various subtypes. In some cases, the European task is not the only, nor even the most important, function of the organization. The EU is also not always the ‘principal’ and organizations may not uconsider themselves to be essentially European. The organizational landscape we are referring to is both complex and diverse. Nevertheless, there are hundreds of these transnational organizations in Europe.

Transnational organizations are, in a definition expanded from Joosen and Brandsma (Citation2017): (1) public organizations, (2) who are (also) executing EU tasks, with (3) a legal status (in a treaty, directive, covenant). They are (4) organizations employing staff, operating (5) in more than one EU country, possibly also beyond the EU borders. The transnational organization is not a national organization, nor is it a fully EU organization. Many of these organizations operate on the nexus of European policies, regional co-operation, and national laws and regulations (Caesar, Citation2017).

We have explored this unknown territory and produced a probably non-exhaustive list of 370 European transnational organizationsFootnote1. This set of transnational organizations is composed of disparate subtypes with specific, often functional, tasks.

Functionality and regionalism

The landscape is to a large degree governed by a logic of functionality, stressing the functional necessities of regional co-operation (Svensson, Citation2017). Some of the transnational organizations in our list focus on border-crossing issues of transportation, such as the European corridors for transportation along roads, waterways and rails, the functional airspace blocks as well as various international commissions for rivers, such as the Danube, the Rhine and the Elbe. Rivers, roads and flight paths have an unpractical tendency not to stick to national borders. Another major set of organizations follows a regional, much more than a European, logic (Duindam & Waddington, Citation2012). Euregions, for instance, enable transnational cross-border co-operation on specific problems and opportunities in border-crossing regions. There are also tens of border and cross-border regions, connecting close (Norway–Sweden), or not-so close (Sicily–Malta), neighbours; sometimes reaching beyond the EU (Finland–Russia). And some organizations have a clear research focus, such as those in the European research infrastructure and the CERN institute in Switzerland, where the EU is one of the partners (Höne & Kurbalija, Citation2018).

While it is clear that there are huge differences between these organizations, they all share the five features identified above and together they compose a disparate and scattered landscape of mostly functional and often regional governance in Europe. This functional organizational landscape is mostly unknown to the general public and, although there are several studies on the various subtypes, there has in general been very little academic interest in most of these organizations (Caesar, Citation2017) and the important accountability questions they pose (Joosen & Brandsma, Citation2017). We focus on this latter perspective in this article.

Accountability is one of the cornerstones of democratic governance and has been one of the critical perspectives that has accompanied the growth and expansion of the EU (Marks, Hooghe, & Blank, Citation1996; Moravcsik, Citation2002). While a crucial value, accountability is not a set concept, although more and more scholars are using the same base-line definition (Bovens, Goodin, & Schillemans, Citation2014, p. 5). For analytical purposes, three simple questions help to bring focus: asking who is accountable to whom and for what?

The ‘who?’ question

Transnational organizations are not easy to identify. As it is a composite category, there is no unifying legal basis, webpage or organizational entity allowing us in our capacity as scholars, policy-makers or citizens to gain an overview. There are some websites and reports available that provide overviews of subtypes of organizations but they are mostly incomplete, contain redundancies and they are not always up to date. One reason for this lack of overview is that the subcategories are not always mutually exclusive (Medeiros, Citation2011). Building on the existing overviews, an extensive analysis of thousands of online pages of legal documents and some snowball-sampling, we compiled our overview of 370 transnational organizations. It is a mix of fairly disparate organizations, which is common for these types of mapping exercises of delegated governance (Verhoest, Van Thiel, Bouckaert, Lægreid, & Van Thiel, Citation2012). What is less common, though, is that it was hard to find comprehensive information on many of these organizations. Only two thirds of the organizations had their own website. Of those that did have a website, most (85%) provided at least some information about the organization and its activities. We set out to gather some basic facts, such as their budgets or the number of staff they employed, but we had to abandon this exercise because could not find much basic organizational information for many of the transnational organizations.

The existing scholarship on regional co-operation and other transnational organizations was not very helpful either in focusing on the organizational dimension. With the exception of Boisot’s interesting work on CERN (Child, Ihrig, & Merali, Citation2014), there is hardly any research focusing on transnational organizations as organizations; the existing research rather focuses on substantive issues or policies. This is surely a missed opportunity, as these collaborations can be hugely complex and may pose fascinating organizational questions. The German-Dutch Euregio for instance is related to 129 different local government entities and is staffed by ‘some’ 50 employees, it’s website claims, and it is related to policies from four levels of government. These types of complex organizational structures may pose critical questions of coordination (Aalto, Espiritu, Kilpeläinen, & Lanko, Citation2017) and accountability.

Transnational organizations operate at some distance from democratic centres of power and legitimacy, staying under the radar and often operating without any clear lines of accountability. Put more strongly, transnational organizations directly trigger the most important accountability concerns in recent scholarship. Schillemans (Citation2013, p. 11) surveyed the existing empirical accountability research and concluded that the three most salient topics of accountability research are:

Decoupled governance, when policies are delivered by organizations which are decoupled from democratically-elected centres.

Network governance, where policies are set or executed by non-hierarchically related partners, often reaching beyond the public sector (Trumbull, Citation2009, p. 3).

Border-crossing forms of governance.

The ‘for what?’ question

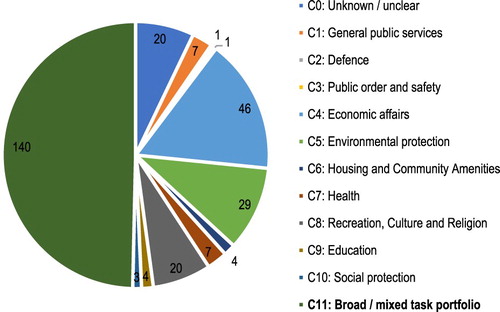

Transnational organizations perform a variety of tasks, relating to transportation, environmental issues, regional co-operation, and research, for which they could be held accountable. In financial and policy research, organizations are often categorized on a set of UN-defined tasks, known by its shorthand ‘COFOG’. We used this to identify the policy areas in which transnational European organizations work. About half of the organizations had either a composite type of task, relating to various policy fields, or the information on their website was difficult to digest for us as outsiders to understand. To provide just one indicative example: ALCOTRA’s (Alpes Latines COopération TRAnsfrontalière) website touches upon most existing policy areas in its opening statements, referring to:

… innovation, safer environment, natural resources, cultural resources, social inclusion, climate change, mobility, employment, education, administrative co-operation, public buildings, tourism, families and young people.

The institutional landscape of transnational organizations is thus complex and difficult to penetrate. This might be the logical outcome of functional logics and regional demands and might even be effective. However, the downside is that citizens—or participants for that matter—do not know and understand those institutional structures which may erode their support and trust. The traditional defence of the complex European institutional architecture is that it generates output legitimacy based on the fruits of its work (Kohler-Koch & Rittberger, Citation2006) which compensates for the lack of democratic input legitimacy through the ballot box. This, however, requires both recognizability of the organization, as well as some level of outcome responsibility for the organization. Tangible results must be traceable and relatable to the organization for output legitimacy to work. Neither of these two criteria are fulfilled for transnational organizations in Europe.

The ‘to whom?’ question

Transnational organizations mostly work both on a regional and a European level. As a consequence, their primary accountability forums, or principals, can be either local, regional, national or European. A limited survey was sent out to the leaders of a smaller set of transnational organizations, confirming that they had multiple accountability relations towards different levels (Kremers, Citation2017). The local or regional level was found to be more important than the European level, even though many of these organizations had some European legal basis, were financed by the EU, or were regulated by EU laws, directives or regulations. This survey also asked the leaders of these organizations to whom they ‘felt accountable’, using a new validated scale with 10 questions (Overman et al., Citation2018). The measurement was applied in a survey with a limited sample (only 40 responses), so we cannot generalize. Nevertheless, as a first indication, it was interesting to see that most respondents indicated they didn’t really feel accountable towards either regional/national or European policy centres.

This is not to say that this first indication suggests there is no accountability. Transnational organizations in Europe are embedded in complex networks with partners, boards, several governments and functional co-operates; the point could be that accountability is much more dispersed. This suggests that the organizational world of Europe may look quite different from the unified, imperial hegemon featuring so prominently in current debates, for instance surrounding Brexit. At least this part of the European public world looks much more like Marks et al. (Citation1996, p. 371) suggested more than two decades ago:

Multi-level governance does not confront the sovereignty of states directly … states in the European Union are being melded gently into a multi-level polity.

Opening up to citizens

A final consideration would be the relationship with citizens in the democratic polity. A key point in the debate about the EU’s lack of accountability is that the EU does not have strong ties to citizens (Follesdal & Hix, Citation2006, p. 553). European institutions are complex and difficult to understand. These points are also hugely relevant in relation to transnational organizations (Engl, Citation2016; Ryan, Citation2014). We are not suggesting that the world of transnational organizations in Europe is necessarily problematic. However, it is important to acknowledge its existence and to explore this unknown territory. After all, if ‘distance to the electoral process and to citizens’, ‘complexity of institutional settings’ and ‘jurisdictional struggles’ between different layers in multi-level systems of governance, are central to the long-lasting debates on accountability in Europe (Bovens, Curtin, & Hart, Citation2010; Hooghe et al., Citation2001; Moravcsik, Citation2002), then the unknown world of transnational European organizations definitely requires our attention.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Gijs Jan Brandsma, Antonia Sattlegger, and Manuel Quaden for their contributions which made this article possible.

This article is part of the 2015-NWO-vidi project Calibrating Public Accountability. https://accountablegovernance.sites.uu.nl/

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

References

- Aalto, P., Espiritu, A. A., Kilpeläinen, S., & Lanko, D. A. (2017). The coordination of policy priorities among regional institutions from the baltic sea to the arctic: The institutions–coordination dilemma. Journal of Baltic Studies, 48(2), 135–160. doi: 10.1080/01629778.2016.1210660

- Arter, D. (2000). Small state influence within the EU: The case of Finland's ‘Northern Dimension Initiative’. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 38(5), 677–697.

- Bovens, M., Curtin, D., & Hart, P. T. (Eds.). (2010). The real world of EU accountability: What deficit? Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Bovens, M., Goodin, R. E., & Schillemans, T. (2014). The Oxford handbook public accountability. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Caesar, B. (2017). European groupings of territorial co-operation: A means to harden spatially dispersed co-operation? Regional Studies, Regional Science, 4(1), 247–254. doi: 10.1080/21681376.2017.1394216

- Child, J., Ihrig, M., & Merali, Y. (2014). Organization as information–A space odyssey. Organization Studies, 35(6), 801–824. doi: 10.1177/0170840613515472

- Dawson, M. (2015). The legal and political accountability structure of ‘Post-Crisis’ EU economic governance. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 53(5), 976–993.

- Duindam, S., & Waddington, L. (2012). Cross-border co-operation in the rhine-meuse region: Aachen (d) and heerlen (nls). European Journal of Law and Economics, 33(2), 307–320. doi: 10.1007/s10657-010-9192-9

- Egeberg, M., & Trondal, J. (2011). EU level agencies: new executive centre formation or vehicles for national control? Journal of European Public Policy, 18(6), 868–887. doi: 10.1080/13501763.2011.593314

- Engl, A. (2016). Bridging borders through institution-building: The EGTC as a facilitator of institutional integration in cross-border regions. Regional & Federal Studies, 26(2), 143–169. doi: 10.1080/13597566.2016.1158164

- Follesdal, A., & Hix, S. (2006). Why there is a democratic deficit in the EU: A response to Majone and Moravcsik. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 44(3), 533–562.

- Hooghe, L., Marks, G., & Marks, G. W. (2001). Multi-level governance and European integration. Rowman & Littlefield.

- Höne, K. E., & Kurbalija, J. (2018). Accelerating basic science in an intergovernmental framework: Learning from CERN's science diplomacy. Global Policy, 9, 67–72. doi: 10.1111/1758-5899.12589

- Joosen, R., & Brandsma, G. J. (2017). Transnational executive bodies: EU policy implementation between the EU and member state level. Public Administration, 95(2), 423–436. doi: 10.1111/padm.12311

- Kohler-Koch, B., & Rittberger, B. (2006). The ‘governance turn’in EU studies. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 44, 27–49.

- Koppell, J. G. (2010). World rule: Accountability, legitimacy, and the design of global governance. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Kremers, G. (2017). Op de grens van de Europese Unie en haar lidstaten. Onderzoek naar verantwoording van transnationale Europese organisaties. Utrecht: Utrecht University.

- Marks, G., Hooghe, L., & Blank, K. (1996). European integration from the 1980s: State-centric v. multi-level governance. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 34(3), 341–378.

- Medeiros, E. (2011). (Re) defining the Euroregion concept. European Planning Studies, 19(1), 141–158. doi: 10.1080/09654313.2011.531920

- Moravcsik, A. (2002). Reassessing legitimacy in the European union. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 40(4), 603–624.

- Overman, S., Schillemans, T., Laegreid, P., Fawcett, P., Fredriksson, M., Maggetti, M., Papadopoulos, Y., Rubecksen, K., Rykkja, L. H., Salomonsen, H., Smullen, A., & Wood, M. (2018). Comparing governance, agencies and accountability in seven countries. CPA Survey Report. Utrecht University School of Governance.

- Ryan, L. (2014). Governance of EU research policy: Charting forms of scientific democracy in the European research area. Science and Public Policy, 42(3), 300–314. doi: 10.1093/scipol/scu047

- Schillemans, T. (2013). The public accountability review. A meta-analysis of public accountability research in six academic disciplines (Working Paper). Utrecht University School of Governance.

- Svensson, S. (2017). Health policy in cross-border co-operation practices: The role of Euroregions and their local government members. Territory, Politics, Governance, 5(1), 47–64. doi: 10.1080/21622671.2015.1114962

- Trumbull, N. (2009). Fostering private–public partnerships in the transition economies: HELCOM as a system of implementation review. Environment and Planning: Government and Policy, 27(5), 858–875. doi: 10.1068/c0788

- Verhoest, K., Van Thiel, S., Bouckaert, G., Lægreid, P., & Van Thiel, S. (Eds.). (2012). Government agencies: Practices and lessons from 30 countries. London: Springer.