ABSTRACT

Whereas there are numerous articles about the extent to which auditors meet the expectations of others regarding the way in which they carry out their tasks (i.e. the audit expectation gap), no literature is available on this same question regarding management accountants. Analysing survey data from management accountants and their managers working in public and not-for-profit organizations, this article shows that such a ‘management accountants’ expectation gap’ does exist as there is, on certain aspects, a difference between the expectations of managers regarding the role of the management accountant and the extent to which these expectations are met.

IMPACT

The management accountant in the public and the not-for-profit sector advises the organization and its management on formulating, realizing and evaluating social and financial results, the organization and functioning of the management control system and accountability. Research shows that there are differences between public managers’ expectations regarding the role of management accountants in the public sector and the extent to which these expectations are met. The effectiveness of management accountants partly depends on the extent to which they meet management’s expectations with respect to their role. This article shows that managers want their management accountants to give more advice without being asked to do so, but the independent attitude, that inevitably plays a role in this, is less appreciated.

Both auditors and management accountants (in The Netherlands, typically referred to as ‘controllers’) play an important role in steering and controlling organizations, but with different emphases. The auditor’s work mainly focuses on determining the correctness and completeness of the financial statements, so that external users, such as shareholders, banks and other interested parties, can depend on the reliability of these documents. This is also referred to as the ‘trust’ function: the auditor’s judgement contributes to the way in which external parties can trust the financial statements, so that there is a certain guarantee for them to use these when making their own decisions (for example investment decisions). The management accountants’ field of activity is broader and less strictly defined. What they do in an organization depends to a large extent on the situational content of their job.

Whether or not auditors meet expectations and requirements is the topic of frequent discussions and numerous publications about the ‘audit expectation gap’. However, as far as we know, no literature is available on this same question regarding management accountants. This article explores whether a ‘management accountants’ expectation gap’ exists. We analyse to what extent expectations regarding tasks and role completion, as well as views of their effectiveness, differ among management accountants and their managers working in public and not-for-profit organizations. Before presenting our empirical results, we first discuss some insights offered by literature available on the ‘audit expectation gap’.

Literature review

The audit expectation gap can be defined as the extent to which auditors meet the expectations of others regarding the way in which they carry out their tasks. Porter (Citation1993) states that there are two possible gaps:

A gap between expectations in society regarding the way in which auditors carry out their tasks and what is reasonable to expect from auditors (‘unreasonable expectations’).

A gap between what is reasonable for society to expect from auditors and the impression people have of the effectiveness of auditors’ work (‘performance gap’).

The performance gap can be divided into two separate gaps:

A gap between what is reasonable to expect from auditors and their current responsibilities, as determined by law and professional standards (‘deficient standards’).

A gap between perceptions of the effectiveness of the way in which auditors carry out their tasks and what may be reasonable to expect from auditors based on the law and professional standards (‘deficient performance’).

Whereas auditors mainly focus on external stakeholders, management accountants’ mainly focus on internal stakeholders. Therefore, it is important to determine to what extent the tasks and performance of management accountants meet the wishes and requirements of the internal management as their major ‘customer’.

As discussed above, the academic literature about the audit expectation gap distinguishes two gaps. One of these relates to expectations regarding task performance. Society may have different expectations from auditors than they can reasonably meet (unreasonable expectations). For management accountants we operationalize this gap by (1) visualizing whether there are any differences (and, if so, what differences) between the task definitions of management accountants and their management (what tasks does the management accountant have to perform?); and (2) whether there are any differences between management accountants’ and their managers’ views of what their duties should be.

We translate the second (performance) gap as the difference between managers’ expectations of management accountants’ performance and its effectiveness.

Before we present the results of our empirical research into these gaps, we will briefly discuss the position of the management accountant in the public sector.

Management accountants in the public sector

In our research we looked at the task and role completion of management accountants working in government and non-profit organizations. This official (the public controller) can be defined as follows (Budding & Wassenaar, Citation2018):

… the public controller advises the organization and its management on request or not, regarding formulating, realizing and evaluating social and financial results, the structure and operation of the management control system and reporting and accountability issues. The public controller collects, analyses and advises in an independent and objective way.

Following NBA-VRC (2014), Budding, Schoute, Dijkman, and De With (Citation2019) describe four content domains in which management accountants are active, both within the for-profit sector and in the public and not-for-profit sector:

Strategic management (for example advising management by offering decision support, analysing and advising regarding strategy, co-operation with other parties and the efficiency of products, services and customers).

Performance management (for example advising on cost-saving and revenue-generating plans, advising on cost prices, advising on evaluation of performance measures).

Finance operations and reporting (for example advising on and creating financial reports, advising on drawing up budgets, making budget reports).

Governance risk and compliance (for example advising with regards to risk management).

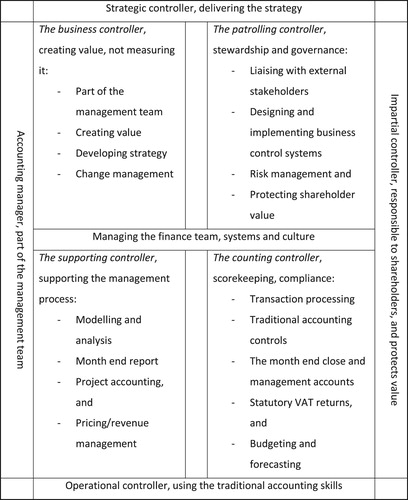

In this article we do not only look at the activities performed by management accountants in the public and not-for-profit sector, but we also analyse the role and position of this official. We consider the model of Graham, Davey-Evans, and Toon (Citation2012) as a useful tool. In this model, the role and position of the controller are distinguished on two dimensions: the dimension of independence versus involvement, and the dimension of operational versus strategic (see ).

Figure 1. The role of the financial controller. Source: Graham et al. (Citation2012).

The traditional role of management accountants is strongly operational, carrying out such activities as the drawing up of annual reports and facilitating the planning and control-cycle (the ‘supporting’ or ‘calculating controller’). These activities are financial to a large extent and are more distant from management. In practice, the calculating controller is also called the ‘financial controller’. Over time, management accountants’ activities have changed. The role has become more strategic, so that tasks regarding scenario-development, risk management and efficiency research are included. This more advisory role is closer to management. For management accountants in these quadrants the terms ‘business controller’ or ‘patrolling controller’ are used. The second dimension in is the one between involvement and independence. The business controller and the supporting controller are more involved, as opposed to the patrolling and calculating controller, who are more independent.

Research method

To get an impression of the management accountants’ expectation gap, a survey was sent in June 2018 to a group of management accountants, participating in a seminar about management accountants working in public sector organizations. These participants were asked to fill out a survey themselves, and to request a line manager in their own organization to do so as well. There were 89 participants at the seminar, of whom 46 filled in the questionnaire (a 52% response rate). Furthermore, 37 managers participated. The respondents were asked to indicate, on a five-point Likert scale (five expressing full agreement, one expressing complete disagreement), what their opinion was on certain statements and questions. Due to the fact that the survey was filled in anonymously, we are not able to investigate the relation between individual opinions of controllers and their own managers.

Findings

Content domains of management accountants

The first question was about the differences in task definition between management accountants and their managers, in which a distinction was made between the importance, the level of attention and the level of effectiveness in the four domains mentioned.

shows that there were hardly any differences between management accountants and managers regarding the extent to which the four domains were dealt with. However, it is remarkable that the management accountants found tasks in the area of strategic management the most important, whereas the managers give more weight to tasks in the field of finance operations and reporting.

Table 1. Differences in tasks.

Table 2. Characteristics of management accountants.

Table 3. Roles of management accountants.

Both groups thought that almost all domains should be receiving more attention from management accountants. Finance operations and reporting was an exception—managers thought that management accountants should pay more attention to this domain, whereas management accountants thought that the attention currently given was sufficient.

Another element was whether the activities in the domains were considered effective, i.e. what distance was experienced between the effectiveness of the task performance and its importance? Both managers and management accountants thought that the activities in the field of finance operations and reporting were the most effective. Both groups also agreed that the activities in the field of governance, risk and compliance were the least effective.

A next step in our analysis was to determine if (and, if so, to what extent) there was a gap between the importance of the tasks and the effectiveness of task performance. On a five-point Likert scale, there turned out to be (on average) a 1.0 difference between the effectiveness of task performance and its importance. The gap between effectiveness and importance was largest in the domain of strategic management (for management accountants and managers 1.13 and 1.19 respectively) and smallest in the domain of finance, operations and reporting (0.76 for both groups).

Role and position

Our second theme is the role and position of the management accountant in the organization. Following Graham et al. (Citation2012), a distinction was made between ‘involved’, ‘independent’, ‘supporting’, ‘strategic’ and ‘operational’ management accountants.

Management accountants want to be more independent in their judgement than managers find desirable and necessary. Apparently there is some tension between what management accountants find desirable and the space they get from management. Furthermore, management accountants wanted to be seen less as operational than managers wanted them to be. In daily practice, management accountants are—according to themselves—too focused on operational activities and not enough on strategic activities. Furthermore, both managers and management accountants saw room for improvement with regard to the involvement of management accountants and how independent they are.

Task performance

Linking up with the definition of a management accountant in the public sector given previously, we asked both groups for their opinions regarding four aspects on the extent to which this task performance is desired and actually exists. This concerns the following aspects: ‘advising on request’, ‘advising without request’, ‘connecting social and financial results’, and ‘objectivity’.

Advising without request is done significantly less by management accountants than their managers would wish and they were also aware themselves of the fact that they would want to do this more intensively. Furthermore, both management accountants and managers thought that advising on request should be done more frequently. This was also the case with regard to connecting societal and financial results. Finally, the objectivity of management accountants can be enlarged, according to both groups.

Discussion and conclusion

In contrast to auditors, no research is available regarding the extent to which management accountants meet the expectations of their stakeholders.

Our research shows that management accountants and managers largely think similarly about the question what tasks are to be performed. ‘Advising without request’ is done significantly less frequently by management accountants than their managers would want. They also think that they should do this more often themselves. Management accountants consider themselves more objective than their managers think they are. Managers believe that management accountants are too focused on operational matters—an opinion management accountants agree with. Lastly, management accountants would like to be more independent in their judgement than managers think is desirable and necessary. Some tension is visible in the attitude of managers. They invite management accountants to give more advice without request, but the independent attitude that inevitably plays a role in this is less appreciated.

To summarise, we can conclude that, on certain aspects, there is definitely a management accountants’ expectation gap, as there is on certain aspects a difference between the expectations of managers regarding the role of the management accountant and the extent to which these expectations are met.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Budding, G. T., Schoute, M., Dijkman, A., & De With, E. (2019). The activities of management accountants: Results from a survey study. Management Accounting Quarterly, 20(2), 29–37.

- Budding, G. T., & Wassenaar, M. C. (2018). De veranderende rol van de public controller. Boom Bestuurskunde.

- Graham, A., Davey-Evans, S., & Toon, I. (2012). The developing role of the financial controller: Evidence from the UK. Journal of Applied Accounting Research, 13(1), 71–88. doi: 10.1108/09675421211231934

- Porter, B. (1993). An empirical study of the auditors expectation-performance gap. Accounting and Business Research, 24(93), 49–68. doi: 10.1080/00014788.1993.9729463