IMPACT

Policy-makers frequently neglect the ways in which social policies are funded through taxation. This relationship is of critical importance because misalignment can cause social policy failure and tax injustice. This is evident with National Insurance (NI): a tax used primarily to fund the UK’s state pension entitlement. This paper explains how NI is failing women and poorer people, prompting questions of why such a poorly designed, unfair and ineffective tax has persisted for so long in the UK. The paper proposes a radical solution: the payment of a universal basic pension and the abolition of NI, with consequential adjustments in income and corporation taxes to compensate for revenue losses.

ABSTRACT

This paper makes a rare contribution to understanding how taxation is used to fund social welfare, and the implications of that relationship. In the UK, National Insurance (NI) is a hypothecated tax used primarily to fund state old age pensions—a contributory welfare benefit. Through historical analysis, and the exemplar of the raising of the state pension age for women, this paper demonstrates that NI fails women and poorer people more than men and the better-off: creating serious problems of social equity. A solution is proposed: the abolition of NI with consequential adjustments to income and corporation taxes, and the introduction of a universal basic pension.

Funding retirement

Lengthening European life expectancy makes older people increasingly dependent on accumulated personal financial resources and other monetary entitlements to sustain themselves when they cease, or reduce, their work. Those with too little income in their working lives to accumulate sufficient savings, or who do not save enough, pose significant social policy challenges.

European states have long sought to manage and mitigate such risks through three principal financial measures:

First, they incentivize (through tax reliefs) or require personal provision such as savings, private insurance and pension schemes.

Second, since the late 19th century in Europe, some people’s inability to make adequate private provision for retirement has prompted the development of state-run social insurance schemes (Ferrera & Rhodes, Citation2000). Entitlement is based on having made the requisite level of monetary ‘contributions’, akin to insurance premiums, and benefits are funded from these contributions rather than general tax revenues (Clasen, Citation2001).

Third, states make cash transfers or passported non-cash entitlements (‘welfare benefits’) to those outside of social insurance schemes, or inadequately protected by them (Waine, Citation1995). These arrangements are not contractual in the legal sense but can be seen as part of the implicit social contract that underpins taxation (Boden et al., Citation2010) and payments are contingent on need, not contributions made.

All three approaches necessitate funding through taxation, but the important, complex relationship between taxation and social policy has been woefully neglected in policy-making and by researchers (Boden, Citation2005; Ruane et al., Citation2020). This paper seeks to start to address this lacuna through critical examination of the UK’s National Insurance (NI) scheme. Badged as a social insurance scheme, of the £106 billion in NI contributions in 2018/19, some £96.7 billion was paid out in pensions (HMRC, Citation2019). NI is therefore pre-eminently a vehicle for funding state pensions (Skinner & Robson, Citation1992).

The NI scheme currently requires employees, their employers and the self-employed to make contributions contingent on levels of wages/salaries and profit from self-employment. Contributions are not payable on unearned income such as pensions, rental or investment income, or on the earned income of those over the state pension age. Contributions are paid into the National Insurance Fund (NIF), which works on a continuous funding basis; the fund typically holds only about one sixth of its annual income as reserves, with no capacity to borrow (Adam & Browne, Citation2006). Government has always absorbed surpluses and made up deficits (Reed & Dixon, Citation2005). By 2018–2019, the NIF’s accumulated notional surplus of £30 billion had all been absorbed into the Consolidated Fund and spent elsewhere (HMRC, Citation2019). Continuous funding means that current workers and their employers pay current state pension recipients (Select Committee on Social Security, Citation2000) in a substantial system of inter-generational wealth transfer. Workers have an expectation, under a very loose social contract, that future generations will similarly pay their pensions.

The rapid pace of labour market and social change can mean that, of necessity, complex, old age risk-mitigation schemes such as NI may suffer ‘institutional misalignment’ with the problems they were designed to tackle (Ferrera & Rhodes, Citation2000, p. 260). Correcting such misalignment can be complex and hampered by long time scales which ‘bake in’ provision, law, political expediency and citizens’ expectations (Hills, Citation2003), leading to ad hoc reforms which may ultimately fail or generate controversy. This paper argues that this is evident with NI. Originally a state-operated workers’ insurance scheme, it has, with very little policy attention, morphed into a regressive hypothecated tax which delivers what is effectively a discretionary welfare benefit masquerading as an individualized contractual entitlement. The consequences of such a poorly designed aspect of public finance that funds a major aspect of social policy have been evident in recent controversies over the raising of women’s state pensionable age, used as an exemplar in this paper, and include social injustice, economic inefficiency and low public confidence and trust. In conclusion, I argue that the nature of NI is occluded from public understanding for reasons of political expediency that have serious social justice implications and make suggestions for radical reform. This paper makes no direct comparison with schemes in other countries. European countries have long-standing state pension arrangements, but these are both heterogenous and complex, and nested within diverse social circumstances and other pension provisions. The UK’s problems are unique, and urgently require a customized solution.

The National Insurance story

The history of NI substantially determines how state pension provision is now funded (Bozio et al., Citation2010). Despite the fact that most NI contributions are now paid as pensions, the scheme retains many of its principal attributes from its origins in 1911 as an unemployment insurance scheme, and from a major reform immediately after the Second World War, when it became the bedrock of the welfare state. In contrast, the labour market and social conditions that state pensions were designed for have dramatically changed.

Living past the age at which one could work to sustain oneself was a significant risk for many workers at the start of the 20th century—although few lived much beyond the age of 65 (Ferrera & Rhodes, Citation2000). In contrast, retirement is now an expectation and normalized as ‘a distinct phase in people’s existence’ (Ferrera & Rhodes, Citation2000, p. 267). The state pension plays a central role in supporting older citizens, accounting for £5.70 of every £10 of income for those over 65 years old (FT Advisor, Citation2018). The poorer three income quintiles are particularly reliant on it (). Women are considerably more reliant on the state pension than men; they tend to have inferior occupational pension provision because of the gender pay gap and career breaks for caring responsibilities (Foster & Heneghan, Citation2018).

Table 1. People aged over 65: source of income by decile.

The early foundations of NI

A state old age pension was first introduced to the UK in 1908 as a welfare benefit, which distinguished between the so-called ‘deserving’ and ‘undeserving poor’ (Peacock & Peden, Citation2014). The Liberal Party governments of 1906 to 1915 drove through a substantial programme of social reform and, in an early act of policy borrowing, the 1909 Budget announced that the UK would follow Germany’s lead and introduce social insurance for workers. The National Insurance Act 1911 established a social insurance scheme to mitigate workers’ risks of unemployment and sickness and, in 1925, pensions were brought within NI—with non-discretionary pension entitlements based solely on the individual’s contribution record (Pemberton, Citation2017). The creation of NI presaged the demise of the 300-year-old Poor Law system of charitable relief. While the Poor Laws facilitated the exercise of social control by discriminating between the deserving and undeserving poor, NI gave workers quasi-contractual entitlements (Ferrera & Rhodes, Citation2000).

NI initially required contributions from workers in closely specified industries, their employers and the government. It built upon existing provision by recruiting trades unions and friendly societies already operating worker insurance schemes to collect weekly contributions on the government’s behalf (Peacock & Peden, Citation2014). Some commercial insurance firms were eventually approved as collection agencies. Bringing a multitude of local schemes together allowed more efficient mutual risk management, especially as previous trade union schemes were based on single industries (Johnson, Citation1992). The risk specificity was relatively high for a narrowly defined pool of members. These origins within existing schemes and organizations helped, crucially, to badge NI as an insurance scheme as opposed to a welfare benefit—an identity that persists.

At this time, most employees making contributions earned insufficient to be liable to income tax (Peacock & Peden, Citation2014), making NI an additional and distinct government revenue stream—as it remains. This additional fiscal burden was initially far from universally popular. One famer in rural Scotland refused to pay his employer contributions and incited his workers to resist, leading to the Turra Coo riots when his cow was seized by officials and put up for sale (Hitchings, Citation2006). There are further points of distinction from income tax: NI contributions were (and largely still are) levied on the pay period (weekly or monthly) not annually; were (and still are) only chargeable on earned income (wages and salaries); and NI rates were (and still are) quite different from income tax (Reed & Dixon, Citation2005). NI contributions and taxes were originally administered by separate agencies. These points of distinction serve to cement the notion that making NI contributions buys a specific and distinct entitlement akin to paying private insurance premiums. With its contributory principle, NI constitutes a form of contractualism (Johnson, Citation1992), differentiating it from charitable or welfare relief.

Early on, contributions were flat rate, regardless of an individual’s risk. The scheme paid fixed benefits to those who had made sufficient contributions over a minimum threshold (Peacock & Peden, Citation2014), rather than there being a direct relationship between payments made in and out (Reed & Dixon, Citation2005)—a principle that still holds, despite contributions now being largely income-contingent. Despite its identity as insurance, the range and nature of benefits was (and still is) determined by government policy, and benefits can and do vary in value regardless of an individual’s contribution record. NI entitlements therefore embody a significant measure of government discretion. The social (as opposed to legal) nature of the NI contract permitted government to back away from making contributions at its original level, which it did as early as the 1920s. Employers’ and government’s contributions gave a degree of wealth transfer to scheme members from capital and taxation.

Extensive unemployment during the 1930s Great Depression necessitated significant additional government funding of NI, along with a controversial cut in unemployment benefits in the 1930s, challenging this contributory principle further. This shifted NI towards being more solidary and redistributive, stalling a move towards extending obligatory private insurance schemes (Johnson, Citation1992). Substantial social change during and immediately after the Second World War necessitated new approaches to individuals’ socio-economic risks. The Beveridge Report on Social Insurance and Allied Services (Citation1942) proposed a welfare state that was operationalized through the National Insurance Acts of 1945 and 1949. At this point, NI stopped being defined as a workers’ insurance scheme of limited scope and became the bedrock of the welfare state.

The Beveridge Report was premised on a male breadwinner paradigm in which families were formed of a (heterosexual) married couple who stayed together (divorce was still relatively rare) and where full-time, life-long paid work was the norm. The system was designed primarily to catch those who fell out of this life and assist them swiftly back into it (Clasen, Citation2001). The reformed NI scheme was well designed to deliver this. There was to be a safety net of cash transfers for those fell outside of NI, which was known as ‘National Assistance’. While the National Assistance Act 1948 formally abolished the Poor Laws, heralding welfare benefits based on need, rather than whether someone was deserving or undeserving, NI remained firmly based on the contributory principle, not proven need (Clasen, Citation2001).

With the implementation of Beveridge, NI was extended beyond the original specified industries and contributions became compulsory for all employers, employees and the self-employed on earned income. Government also committed to making a financial contribution. This allowed greater risk pooling and extended mutuality. The government adopted Beveridge’s suggestion of fixed-rate contributions and benefits. Beveridge’s original plan was that NI benefits would be set at ‘subsistence’ level, although this was never achieved in practice (Select Committee on Social Security, Citation2000). The intention of this capping was that it would allow those of sufficient means to make private provision for more generous income replacement and pensions (Clasen, Citation2001). The range of benefits was wide, but the main ones were, and remain, unemployment benefits and the state retirement pension.

Post 1945 changes

Britain experienced substantial social and economic change from the 1950s, necessitating adaptation of this system to emerging needs. More people were working part-time or having interrupted careers, jobs were no longer for life, women were entering the workforce in greater numbers, divorce was more common, and people were living longer (Select Committee on Social Security, Citation2000). In the 1960s and 1970s the range of benefits was expanded, especially after a shift from fixed-rate to income-contingent contributions pumped more money into the scheme. This was matched in the 1970s by an experiment with NI benefits that offered income-contingent wage replacement (Clasen, Citation2001) and earnings-related pensions above the basic state pension. Government started granting NI credits in lieu of cash contributions—for example, to those looking after young children at home. At the same time, government took the opportunity of significant NI surpluses to take holidays from payment (Adam & Browne, Citation2006). Government contributions were phased out entirely by the 1990s—the final withdrawal marked also by an income tax cut at the expense of an increase in NI contributions (Hills, Citation2003). By 1979, the value of the full state basic pension had peaked at 26% of average national earnings (Financial Times, Citation2015).

These developments were short-lived. In the 1980s and 1990s, under successive Conservative governments, the value of NI benefits was reduced and there was a concomitant shift towards income-contingent cash transfers (Hills, Citation2003). This gave greater power to government to restrict payments or to obstruct entitlement through rule changes than is possible with social insurance (Peacock & Peden, Citation2014). By 2017–2018, out of a total welfare spend of £178.2 billion, expenditure on contributory benefits was £102.1 billion but, of that, £95.5 billion went on state retirement pensions. Of total welfare expenditure excluding pensions, some 92% was by non-contributory cash transfer (HM Government, Citation2018).

As well as shifting emphasis away from contributory benefits to cash transfers, the Conservative governments pushed for a transition from reliance on the state pension to private provision by simultaneously providing tax incentives (Foster & Heneghan, Citation2018) and reducing the value of the state pension. By 1980, the Thatcher government had decoupled state pension increases from average earnings and instead linked them to retail price increases. As incomes growth outstripped retail inflation over the next 30 years, the value of the pension as a proportion of average earnings fell dramatically—to a low of 15.8% in 2008 (Financial Times, Citation201Citation5). Income-contingent NI contributions remained strong as incomes grew, with the accumulated excess probably funding the rising cost of meeting women’s growing pension entitlements. In 2010, a Conservative–Liberal Democrat government introduced the so-called ‘triple lock’, whereby the state pension rises by the highest of earnings growth, retail price increases or 2.5%. By 2017, the state pension had increased to 24.2% of average national earnings—as opposed to an OECD average of 42.5% (Pensions Policy Institute, Citation2017).

This brief history demonstrates that while NI as a fundraising mechanism and its public presentation as a social insurance scheme has altered remarkably little since at least the Beveridge Report in 1942 and, indeed, 1911, government’s actual construction of the pension entitlements it funds has changed dramatically. The contributory principle has been substantially eroded in practice—meaning that the state pension has become very much less of an insurance payment and more a welfare benefit or cash transfer. However, NI is still presented to the public as a social insurance scheme. The tensions inherent in this situation have been made evident by recent controversies over women’s state pensions.

Retiring women?

When state pensions were first introduced in 1908, the retirement age for both men and women was 70. In 1925, when pensions became part of NI, this was reduced to 65. In 1940, women’s state pension age was reduced to 60. It appears that this was because women were disproportionately caring for elderly relatives and so less likely to be working, and because men tended to marry women who were around five years younger than themselves (Pemberton, Citation2017).

Good grounds for this differential may persist. Women were (and still are) more likely to have to give up work to care for relatives. Until the introduction of the Part-time Workers (Prevention of Less Favourable Treatment) Regulations 2000, it was common for part-time workers, most of whom were women, to be excluded from occupational pension schemes. Even women in such schemes were (and still are) are frequently likely to be on the wrong side of the gender pay gap or have taken career breaks for caring, which adversely affects their pension entitlements. Women’s extra five years’ state pension gave some compensation, but it is moot whether this was an efficient delivery mechanism.

Despite this, by the 1960s and 1970s, these differential state pension ages looked increasingly anomalous. Equalization downwards (a reduction to 60 for men) was the favoured option but was found to be too costly (DHSS, Citation1978). A proposal to split the difference and settle halfway between the men’s and women’s age was likewise too costly; because of the differences in male and female labour market participation, the cost-neutral equalization point was 64.5 years (Pemberton, Citation2017). In the 1980s, attempts at equalization downwards were still found infeasible on cost grounds (Thurley & McInnes, Citation2019).

Upwards equalization came following a European Court of Justice ruling in 1990 in the case of Barber v Guardian Royal Exchange, in which Mr Barber argued successfully that it was discriminatory for his employer’s occupational pension scheme to allow women to access their pensions earlier than he could. By the 1990s, increasing numbers of women were qualifying for substantial state pensions in their own right, placing the pressure on the NIF (Johnson & Stears, Citation1996). The government seized its opportunity, even though the Barber ruling did not apply to state pensions, to enact the Pensions Act 1995. This set out a timetable for phasing in equalization at 65 between 2010 and 2020 (Thurley & McInnes, Citation2019). The state pension age for both men and women was raised to 66 in 2007 and then to 67 in 2011. The 2011 changes also accelerated the timescale for equalization from 2020 to 2018 and were driven by austerity measures following the global financial crisis (Thurley & McInnes, Citation2019).

Women in low-paid employment, with no occupational pension and little or no awareness of complicated rule changes, were likely to be the most adversely affected by these reforms (Thurley & McInnes, Citation2019). They were not all directly informed of the changes to their entitlements or told in good time. The Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) only undertook direct mail campaigns to affected women between 2009 and 2013—some 14 to 18 years after the initial changes (Hansard, Citation2016a). Many letters did not reach the addressee because the tax authorities were unable to provide a valid address—something that would have particularly affected low-paid women who are less likely to have to complete a tax return (Thurley & McInnes, Citation2019). The government was aware that there was a failure on its part to inform the affected women: the DWP discussed this in 1998, 2000, 2007, 2011, 2012 and 2015 (Hill, Citation2019). While Pemberton (Citation2017) asserts that there were a number of articles in the financial press, Mhairi Black MP, speaking in a House of Commons debate, stated that:

… when giving evidence to the Work and Pensions Committee, financial journalist Paul Lewis told us that after researching this himself he could barely find any reporting of the issue at all in 1995. There were a few small press cuttings from the business pages at the back of some newspapers. A freedom of information request revealed that the Government did fund ‘broader’ awareness campaigns, which ran in waves between 2001 and 2004, but that these campaigns ‘did not focus on equalization in particular’.

In fact, only one of the press adverts in those campaigns was focused on this issue—one press cutting roughly seven years after this had already been passed into law. It is quite evident that this whole thing became a total mess (Hansard, Citation2016b).

One of my constituents told me that she began working at 17 and chose to pay the full rate of national insuranceFootnote1 on the basis that she would retire at 60. Other options were available to her, but she said, ‘I want to retire at 60 so I’ll pay the price, through national insurance, my whole working life. The coalition and this present government have stripped us of our pensions with no prior warning and with no regard to the contract we all entered when we were 17’ (Hansard, Citation2016c).

She uses the term ‘contract’. That is an important point, because pensions are not benefits; they are a contract. People enter into them on the basis that if they pay x amount of national insurance they will receive y at a certain age.

In civil law, if we enter into a contract, there are terms and conditions stating, ‘If you want to change this contract or break out of it, there will be a price to pay’. Why are pensions any different? This is a contract people have entered into, but it is now being broken and nothing is being done to allow them to transition. These women have done exactly what was asked of them—they have worked hard all their lives and paid their national insurance—but it is now being taken from them from behind their backs (Hansard, Citation2016d).

‘Parliament has no substantive, freestanding obligation of fairness’, Eadie [QC for the government] told a courtroom so packed that many supporters of the action had to wait outside. ‘It’s clear from case law that the enactment of primary legislation carries with it no duty of fairness to the public’ (Hill, Citation2019).

‘There is precisely no obligation on parliament to notify those affected by its judgments’, he said. ‘Indeed, any such suggestion that a duty of that kind exists would be contrary to established principles. There is no basis in principle for the creation of any such duty’ (Hill, Citation2019).

This episode demonstrates how government effectively perceives the state pension to be a benefit over which it holds a very significant amount of discretion and under the terms of which citizens have little or no contractual rights—not even to be informed when substantial changes are made—a view upheld by the courts. Paradoxically and problematically, many citizens perceive NI, the scheme that funds pensions, as an insurance scheme which confers distinct and inalienable rights upon them. Funding impacts provision because of the contributory principle, leading to questions of whether the design of NI as a funding mechanism for the state pension is fit for purpose.

National Insurance—fit for purpose?

This history, and recent events, prompt two fundamental critiques of NI. The first is that, as a fundraising mechanism for welfare policies, sequential ad hoc reforms over more than a century have rendered it deeply flawed in design. The second, and related, critique is that, despite its public face is as a contributory social insurance scheme, NI is a tax-raising mechanism for a discretionary welfare benefit. I address each in turn.

A flawed design

Despite now being administered by the tax authorities, NI persists as a discrete system with its own rules aligned to the historic notion of social insurance contributions yielding specific entitlements. The system holds in place many of its original features, including: the charging base—what NI contributions are levied on; contribution rates, and; the incidence of demands for contributions (who the burden falls on). These archaic aspects and the problems they engender can be demonstrated by exploration of the four current classes of NI contributions, using the rates for 2019–1920.

Class 1: This is paid by employees and their employers on wages/salaries. Unlike income tax, the assessment period is the pay period (weekly or monthly), rather than the tax year.

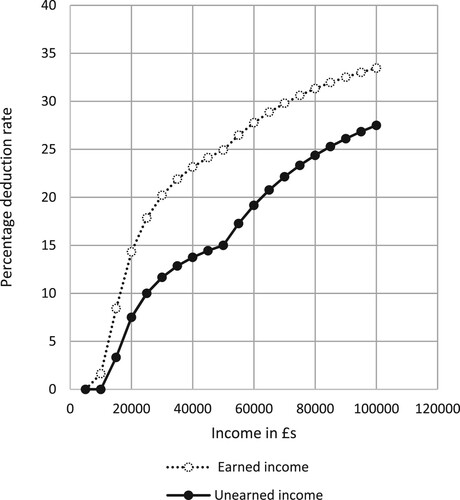

Employees pay 12% contributions on earnings in any week/month between £166/£719 and £962/£4167 (£8628 to £50,000 annually). Above £962/£4167 a week/month, the rate falls regressively to 2% (see ). Basic rate income tax of 20% is payable on earned and unearned income between £12,500 and £50,000 a year, rising to 40% over £50,000. The restriction of the NI base to only earned income creates significant net income disparities between those who live on wages and those who live on pensions or investment income, as shows.

If total annual earned income on which contributions are paid is more than £8628, then that year counts as a ‘qualifying year’. Each qualifying year counts towards the state pension—with the maximum pension reached at 35 qualifying years. So, if someone earns £8629 in a year, they might pay 12 pence in contributions and that is a qualifying year. In a redistributive move, they will then receive the same fixed-rate pension entitlement as someone who pays, say, £12,000 in contributions. However, the short periodicity of NI can cause problems for very low-paid people with highly variable earnings, such as those working in the gig economy. If someone’s earnings in any given week/month go over £166/£719, then they must make NI contributions. However, if their total annual earnings are still under £8628, it will not count as a qualifying year and they accrue no entitlements, despite having paid contributions. These rules are also likely to adversely affect students in higher education with highly variable work patterns.

Employers pay Class 1 contributions on employees’ earnings over £166 a week/£719 a month at a rate of 13.8%. Currently, about 60% of Class 1 contributions come from employers and 40% from employees. NI is thus a significant payroll tax and may disincentivize hiring, and unfairly discriminate between labour-intensive firms and those who are not (Mirrlees et al., Citation2011). Class 1 contributions totalled approximately £98 billion in 2018—the NIF’s largest source of income.

Class 2: These are flat-rate contributions of £3 a week/£156 a year, paid by self-employed people. The minimum threshold for compulsory contributions is annual profits of £6365. Those with profits beneath the threshold can make voluntary contributions to accrue qualifying years. Class 2 contributions totalled around £322 million in 2018.

A contribution of £156 buys a qualifying year, which currently translates into an annual pension entitlement (for every year between the state pension age and death) of around £260. This makes Class 2 an extremely cost-effective way of securing pension entitlements—and a very costly one for the state.

In the 2016 Budget, the government caused controversy with proposals to abolish Class 2 on the grounds that it would ‘simplify’ NI. There was an outcry as it allows low-income self-employed people to cheaply secure state pension entitlements and the proposal was abandoned in 2018 (Written Statement HLWS915, Citation2018).

Class 3: These fixed-rate contributions are entirely voluntary and designed to allow people to boost their qualifying years. The rate in 2019–2020 was £15 a week/£780 annually to purchase a qualifying year. This one-off £780 payment is currently recouped in just over three years of pension payments. This route is frequently used by better-off people who have retired prior to the state pension age because they have a sufficiently generous occupational pension. Class 3 netted appropriately £79 million in 2018.

Class 4: These contributions are paid by self-employed people who earn more than £8632 a year (the assessment period is the year here, not the week or month). In 2019–2020 the charge was 9% on profits between £8632 and £50,000 and 2% thereafter. Self-employed people get no qualifying years or other additional entitlements for their Class 4 payments—there is no ‘insurative element’ (Skinner & Robson, Citation1992, p. 115). Class 4 netted about £32.3 billion in 2018.

State pensions funded by social insurance schemes are aimed at increasing social equity. The design of NI has clear deficiencies in this regard:

First, the incidence of the tax is unfair—for instance, wealthier people who get more of their income from capital assets may pay less in NI contributions than poorer wage-earners yet get the same state pension. All pension receipts are unearned income—exacerbating the inter-generational wealth transfers (Mirrlees et al., Citation2011). Employers who hire workers are disadvantaged vis-à-vis those that don’t. This tax base also allows significant numbers of owner-operators of incorporated businesses to cut their NI bills, and employers’ contributions, by paying themselves minimal salaries, gaining the largest part of their income from dividends instead, while making the contributions necessary to secure qualifying years for the state pension (Burkinshaw, Citation2017).

Second, NI is regressive, with the burden of contributions not increasing progressively with income.

Third, NI has a confusing set of assessment periods which can act to deny entitlements. Thus, the assessment period is weekly or monthly (depending on the pay period), but the income thresholds are annual. Thus, many end up contributing but with the impossibility of accruing a qualifying year. Moreover, the year in which someone reaches the state pension age can never be a qualifying year, no matter what level of contributions they have paid.

Fourth, there is no clear link between payment and entitlement. This could promote social justice if the direction of shift was always from richer people to poorer, but it is not.

Fifth, this system rewards those who have unearned income from capital over those who have earned income from work.

Finally, the absence of any contractual entitlement means that pension rates can and do fluctuate according to government policy, reducing the capacity of citizens to plan adequately for retirement.

This haphazard approach to funding pensions creates consequential problems. Difficulties for some in accumulating qualifying years, combined with the low value of the state pension, mean that the UK has to provide a top-up cash transfer called ‘Pension Credit’ to those on very low incomes who do not receive the full state pension (Bozio et al., Citation2010). Individuals must apply for Pension Credit—meaning that they must know about the benefit and be capable of successfully negotiating the application procedure. This might deter many people who, while comfortable with the supposed contributory nature of the state pension, might feel less accepting of a welfare ‘hand-out’ (Stafford, Citation1998). In August 2019, there were 1.57 million claimants—a very poor take-up rate of around 60% (Thurley, Citation2019). Possibly as many as 1.3 million households are not claiming the Pension Credit to which they are entitled: the total value of which is £3.5 billion—around £2,500 a year for each household (Thurley, Citation2019). At 64% of current claimants, women are disproportionately reliant on Pension Credit (Financial Reporter, Citation2020).

The second profound critique of NI is that it purports publicly to be a social insurance scheme but is, in fact, a scheme that raises funds through taxation. Generically, the contributory principle is a core characteristic of social insurance, implying reciprocity under a solidaristic social contract and embodying mutuality, reasonable certainty for citizens, and socially equitable wealth transfers. This is evidently the type of scheme that the WASPI campaigners perceive they belonged to. While NI does require that individuals pay into the scheme in order to benefit from it, this is only a necessary but not sufficient signifier of whether it is actually a social insurance scheme. A more nuanced reading sees the contributory principle as the expression of a complex set of solidaristic obligations within a social contract (Select Committee on Social Security, Citation2000; Sinn, Citation1996) against which the efficacy and equity of NI should be judged.

The continuously funded nature of NI is more than a mere bookkeeping fact (Johnson & Stears, Citation1996). Contributors do not accumulate funds for their own use, even on a mutual basis. Nor is there a legal obligation on government to pay benefits. Rather, because of the dominance of pensions as NI benefits, contributors participate in a substantial inter-generational wealth transfer from the younger to the older (Sinn, Citation1996; Thurley & McInnes, Citation2019). This unusual financing situation would be expedient if the social contract was clear, mutually accepted and obligations consistently honoured. The evidence suggests that this is not the case, as the raising of women’s state pension age suggests.

Social insurance can be flexible in responding to changing social circumstances, adapting to changing need at the cost of reduced certainty for citizens. However, it is also reasonable that citizens should be able to plan their lives with some degree of certainty as to which of their life risks are covered and to what extent—an aspiration of the WASPI women. The insurative value is therefore contingent on the state respecting the solidaristic social contract, and this is easily reneged on with NI (Adam & Loutzenhiser, Citation2007), as the raising of women’s state pension age demonstrates. Lower-income people, of which the majority are women, are more adversely affected than those who are better off in such circumstances because they have fewer alternative resources.

National Insurance is a tax

That NI is a social insurance scheme is ‘largely a fiction’ (Skinner & Robson, Citation1992, p. 113) as it does not embody a strong link between contributions and entitlements and has significant social justice failings. Rather, NI does have the hallmarks of a tax: it is compulsory, payments to the state (but not the benefits received) are income-contingent and there is some redistributive effect (Mirrlees et al., Citation2011). It is also a hypothecated tax—the intention of the scheme is to earmark revenues raised for specific purposes (Wilkinson, Citation1994; Mirrlees et al., Citation2011).

Hypothecated taxes are either strong or weak. Strongly hypothecated taxes closely match revenue to expenditure—what is collected is what is spent. Weakly hypothecated taxes have only a nominal link between income and expenditure, with government picking up deficits and absorbing surpluses. NI is therefore weakly hypothecated. Hypothecated taxes are also either broad or narrow: covering an entire programmatic area or a specific project. NI contributions are a weak and wide hypothecated tax (Wilkinson, Citation1994).

Proponents of hypothecated taxes argue that they increase the propensity to compliance because taxpayers see a clear link between payment and service delivery, increasing democratic participation and transparency (Wilkinson, Citation1994; Seely, Citation2011). However, hypothecation needs to be strong for such benefits to be fully realized, and even then, may inappropriately bind the hands of government decision making on spending (Wilkinson, Citation1994). Weakly hypothecated taxes, such as NI, may do little more than highlight the government’s expenditure (Wilkinson, Citation1994).

The contributory rhetoric of NI signals to taxpayers, such as the WASPI women, that hypothecation is strong—that money paid in leads to absolute entitlements (Stafford, Citation1998). However, the hypothecation of NI has been described as ‘illusory’ (Adam & Loutzenhiser, Citation2007, p. 21). Seely (Citation2011) argues that taxpayers could become severely disenchanted if they discover hypothecated taxes are not used for the supposed designated purposes and it is evident in the WASPI campaign that such disenchantment has materialized.

Hypothecating taxes should facilitate the targeting of expenditure. In the case of NI, this should engender social equity and certainty in pension provision. However, scheme contribution rules too often exclude those who are most vulnerable, and even poorer people who are not excluded frequently accrue lesser entitlements. Poorer people are therefore made reliant on Pension Credit cash transfers, which represent a greater operation of state power against poorer people than contributory benefits do and have lower efficacy. In the case of UK state pensions, this has a significant gender dimension.

Finally, the dual nature of the personal tax system—NI and income tax—means that there is a massive duplication of administrative costs (Mirrlees et al., Citation2011), which makes NI very expensive (Johnson & Stears, Citation1996).

This begs the question as to why such a poorly designed, unfair and ineffective tax has persisted for so long? It may be that governments find it convenient to be economical with the truth (Mirrlees et al., Citation2011). NI is widely accepted, and compliance is high because of the perceived entitlements, which Wilkinson argues is ‘a matter of faith and expediency (and the faith may be misplaced)’ (Citation1994,, p. 133). The nomenclature of ‘contributions’ obscures the regressive nature and tax base of NI (Wilkinson, Citation1994), obscuring individuals’ effective rate of tax deduction, with government most often talking only of income tax rates (Mirrlees et al., Citation2011). As such, NI can be seen as the operation of power against less well-off people and women.

Ways forward

The distinction between contributory benefits and cash transfers in the UK is reliant on the notion of the contributory principle. This paper has demonstrated that, in the case of NI, this is more honoured in the breach than the observance. NI is a hypothecated tax and not a social insurance scheme. Citizens paying any tax are, at heart, participating in a redistributive social contract with mutual responsibilities on both sides (Boden et al., Citation2010: Sinn, Citation1996). This, in the case of NI, makes the distinction between contributory benefits and welfare cash transfers artificial, to say the least. As such, there is no credible case for retaining NI when alternate tax provisions to fund state pensions could be much more effective at satisfying Adam Smith’s canons of taxation—that payments should be related to the ability to pay; of certainty (as in transparency around the purpose and nature of taxes demanded); of convenience (as in ease and simplicity of payment); and should be economical to collect (Smith, Citation1776).

There has been much discussion in the academic literature about a merger of NI and income tax (for example Adam & Loutzenhiser, Citation2007). However, these are largely proposals to align NI with income tax to address the administration costs and fight shy of radical reform. The fact that NI is now principally a mechanism for funding the state pension offers more profound opportunities for reform. ‘The government estimates that 90% of those reaching state pension age in 2025 will be entitled to the full pension’ (Mirrlees et al., Citation2011, p. 127). Many of those who do not get the full pension will be entitled to Pension Credit. In short, very soon almost everyone will get a full pension or, if low income, is entitled to an equivalent payment via Pension Credit.

This suggests a two-pronged reform:

First, everyone (perhaps with some residence qualification) should be paid a universal flat-rate state pension from general government revenues.

Second, NI should be abolished with consequential adjustments to income tax and corporation taxes to collect the required revenue lost from NI.

This offers a number of advantages. The revised income tax regime could be progressive. Unfair inter-generational financial transfers would be eliminated. Corporate taxes would no longer discriminate against firms that create jobs. The problems with the low take-up rate of Pension Credit would be obviated—significantly relieving pensioner poverty. Administrative costs would be slashed. Honesty to taxpayers regarding their tax contributions would be increased. The WASPI case has highlighted that NI as a social insurance is a chimera—and one that embodies little social justice at that. The prospects of success for those pursuing their legal appeal are possibly quite poor, but the case could have substantial repercussions for future generations if it leads to the veil being drawn back on what NI is and how it operates, and to radical reform.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Until 1977, married women could elect to pay a reduced rate of NI and rely instead on their husband’s pensions—an arrangement indicative of the ways in which NI continues to embody archaic social histories.

References

- Adam, S., & Browne, J. (2006). A survey of UK tax system. Briefing Note No. 9, Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS). Accessed at https://www.ifs.org.uk/bns/bn09.pdf 23 March 2020.

- Adam, S., & Loutzenhiser, G. (2007). Integrating income tax and national insurance: An interim report. Working paper No. 07/21. IFS.

- Beveridge, W. (1942). Social insurance and allied services. Cmd 6404. HMSO.

- Boden, R. (2005). Taxation research as social policy. In M. Lamb, A. Lymer, J. Freeman, & S. James (Eds.), Taxation: An interdisciplinary approach to research. Oxford University Press.

- Boden, R., Killian, S., Mulligan, E., & Oats, L. (2010). Critical perspectives on taxation. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 7(21), 541–544.

- Bozio, A., Crawford, R., & Tetlow, G. (2010). The history of state pensions in the UK: 1948-2010. Briefing Note BN105. IFS.

- Burkinshaw, L. (2017). Personal service companies and the public sector. Public Money & Management, 37(4), 253–260.

- Clasen, J. (2001). Social insurance and the contributory principle: A paradox in contemporary British social policy. Social Policy and Administration, 35(6), 641–57.

- DHSS. (1978). A happier old age: A discussion document on elderly people in our society. HMSO.

- Ferrera, M., & Rhodes, M. (2000). Building a sustainable welfare state. West European Politics, 23(2), 257–282.

- Financial Reporter. (2020). Pension credit claimants plummet for third consecutive year. https://www.financialreporter.co.uk/later-life/pension-credit-claimants-plummet-by-two-million.html.

- Financial Times. (2015). Chart that tells a story—pensions and earnings. https://www.ft.com/content/6f8531d6-ddfd-11e4-8d14-00144feab7de.

- Foster, L., & Heneghan, M. (2018). Pensions planning in the UK: A gendered challenge. Critical Social Policy, 38(2), 345–366.

- FT Adviser. (2018). Over-65s rely heavily on state pension. https://www.ftadviser.com/pensions/2018/12/17/over-65s-rely-heavily-on-state-pension/.

- Hansard. (2016a). https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201516/cmhansrd/cm160107/debtext/160107-0002.htm.

- Hansard. (2016b). https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201516/cmhansrd/cm160107/debtext/160107-0002.htm.

- Hansard. (2016c). https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201516/cmhansrd/cm160107/debtext/160107-0002.htm.

- Hansard. (2016d). https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201516/cmhansrd/cm160107/debtext/160107-0002.htm.

- Hill, A. (2019). No duty of fairness to women hit by pension age rise, court told. The Guardian https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2019/jun/06/no-duty-of-fairness-to-women-hit-by-pension-age-rise-court-told 23 March 2020.

- Hills, J. (2003). Inclusion or insurance? National insurance and the future of the contributory principle. CASE paper 68. http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/5563/.

- Hitchings, E. (2006). GB-1912 The National Insurance Act and the ‘Turra Coo’. The Revenue Journal of Great Britain, XVI(4), 146–148.

- HM Government. (2018). Benefit expenditure and caseload tables 2018. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/benefit-expenditure-and-caseload-tables-2018.

- HMRC. (2019). Great Britain National Insurance Fund account, year ended 31 March. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/839411/Great_Britain_National_Insurance_Fund_Account_-_2018_to_2019.pdf.

- Johnson, P. (1992). Social risk and social welfare in Britain 1870-1939. LSE Working Papers in Economic History, 3(92), https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/94959.pdf.

- Johnson, P., & Stears, G. (1996). Should the basic state pension be a contributory benefit? Fiscal Studies, 17(1), 105–112.

- Just Group. (2019). https://www.justgroupplc.co.uk/~/media/Files/J/JRMS-IR/news-doc/2019/millions-of-the-uks-poorest-pensioners-receiving-the-least-state-support.pdf.

- Mirrlees, J., Adam, S., Besley, T., Blundell, R., Boden, S., Chote, R., Gammie, M., Johnson, P., Myles, G., & Poterba, J. M. (2011). Tax by design. Oxford University Press.

- Peacock, A., & Peden, G. (2014). Merging national insurance contributions and income tax: Lessons of history. Economic Affairs, 34(1), 2–13.

- Pemberton, H. (2017). WASPI’s is (mostly) a campaign for inequality. The Political Quarterly, 86(3), 510–516.

- Pensions Policy Institute. (2017). Everything you always wanted to know about the triple lock but were afraid to ask … https://www.pensionspolicyinstitute.org.uk/media/1364/201705-bn96-everything-you-always-wanted-to-know-about-the-triple-lock-but-were-afraid-to-ask.pdf.

- Reed, H., & Dixon, M. (2005). National insurance: Does it have a future? Public Policy Research, 12(2), 102–110.

- Ruane, S., Collins, M. L., & Sinfield, A. (2020). The centrality of taxation to social policy. Social Policy and Society, https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S1474746420000123

- Seely, A. (2011). Hypothecated taxation. Standard note SNO1480. https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/sn01480/.

- Select Committee on Social Security. (2000). The contributory principle. Fifth report Session 1999-2000. https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm199900/cmselect/cmsocsec/56/5604.htm.

- Sinn, H. W. (1996). Social insurance, incentives and risk-taking. International Tax and Public Finance, 3, 259–280.

- Skinner, D., & Robson, M. (1992). National insurance contributions: Anomalies and reforms. Fiscal Studies, 13(3), 112–125.

- Smith, A. (1776). An enquiry into the nature and causes of the wealth of nations. https://www.econlib.org/library/Smith/smWN.html.

- Stafford, B. (1998). National insurance and the contributory principle. https://www.academia.edu/1098884/National_Insurance_and_the_contributory_principle.

- Thurley, D. (2019). Pension credit—current issues. Briefing paper CBP-8135. House of Commons Library.

- Thurley, D., & McInnes, R. (2019). State pension age increases for women born in the 1950s. Briefing Paper CBP-7405. House of Commons Library.

- Waine, B. (1995). A disaster foretold? The case of the personal pension. Social Policy & Administration, 29(4), 317–334.

- Wilkinson, M. (1994). Paying for public spending: Is there a role for earmarked taxes? Fiscal Studies, 15(4), 119–135.

- Work and Pensions Committee. (2016). Communication of state pension age changes . HC 899. https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201516/cmselect/cmworpen/899/899.pdf.

- Written statement HLWS915. (2018). National Insurance Contributions—written statement by Lord Bates, 6 September. https://www.parliament.uk/business/publications/written-questions-answers-statements/written-statement/Lords/2018-09-06/HLWS915/.