IMPACT

Private investors can help governments overcome budget constraints in infrastructure procurement and to increase the quality of infrastructure assets. However, private investors’ engagement can result in inflexibility and high costs for both taxpayers and the users of the infrastructure service. Australia and Canada are forerunners in building successful collaborations with private investors in the infrastructure space. In a three-year project, the authors attempted to get public infrastructure owners still relying on traditional infrastructure procurement to collaborate with institutional investors for the long term. This paper documents the insights received during this journey, providing lessons for countries considering brokering direct investment deals.

ABSTRACT

Infrastructure projects where many partners and technologies must work together to produce a functioning and sustainable outcome are often challenging. Australia, Canada and UK are among the few countries that have actively been rethinking infrastructure procurement. In these countries, the private sector has been given a bigger share in infrastructure projects, and this trend is spreading to other countries. The authors contribute to the literature by investigating infrastructure owners’ and investors’ motives and challenges to engage in closer collaboration in a country using traditional procurement methods. They identify problems in building successful collaboration and suggest ways to overcome these challenges.

Introduction

Infrastructure projects can be viewed either as public assets or as investments. From the public asset viewpoint, infrastructure projects are resources which benefit citizens and society by providing useful services. From the investor viewpoint, infrastructure projects often deliver predictable cash flows for long periods of time. Ideally, there should be a connection between the value the infrastructure assets deliver to the public and the returns earned by investors.

Australia and Canada were among the first countries to allow pension funds to finance infrastructure assets, and these investments have generated good growth and returns (Inderst, Citation2014). Many other countries are now following in their tracks (Vecchi et al., Citation2017). In an environment of low interest rates and lack of investment opportunities with predictable cash flows, investors are keen to invest in infrastructure projects. Usually these investments have been carried out indirectly through a private equity (PE) type of fund structure. According to the alternative investment data provider Preqin (Citation2021) worldwide capital flows into unlisted infrastructure funds were down only 14% in 2020 (from 2019) despite Covid-19. Although Preqin has revised its future estimates slightly downwards due to the pandemic, it still estimates that assets under management (AUM) of infrastructure funds will grow to USD 795 billion by 2025—up from USD 655 billion in June 2020. PE funds typically have maturities that are shorter than the lifetime of the infrastructure asset and they often are highly leveraged, which may not be optimal for pension investments (Panayiotou & Medda, Citation2014). Partly due to this, the trend of pension funds and other long-term institutional investors is to increase the share of their direct investments in infrastructure (Monk & Sharma, Citation2015; Infrastructure Partnerships Australia, Citation2019). Recently, Larry Fink, CEO of the world’s largest asset manager Blackrock, said that his firm wanted to be part of public–private efforts to improve financing mechanisms for sustainable infrastructure investments and urged other CEOs to follow suit (Fink, Citation2020).

For governments that have to provide their citizens and economies with good sustainable infrastructure services, availability of financing is naturally a good thing, but it is often not the most important factor. Deciding whether private sector investors should be given a bigger role in the procurement and governance of infrastructure projects often depends on whether doing this will increase the value of the projects. Based on previous research, there is no simple answer to this question because it depends on the circumstances. The success of letting the private sector have a bigger say regarding infrastructure seems to be dependent on such factors as the country involved; what kind of infrastructure is developed; the objectives of the partners involved; and how success is actually defined (for example Blanc-Brude et al., Citation2006; Siemiatycki & Farooqi, Citation2012; Romero, Citation2015; Boardman et al., Citation2016; Hodge et al., Citation2018; Sundström, Citation2018).

In many countries, private ownership of public infrastructure is generally viewed negatively due to, among other things, poor accountability of projects and high media coverage of unsuccessful public–private partnerships (PPPs) (Hall, Citation2015). Infrastructure PPPs are argued to be costly for taxpayers because of private sector profit-seeking and opportunism (Boardman et al., Citation2016). Transaction costs are high as the deals are often complicated and are often one-offs (Henisz et al., Citation2012). As well, many governments and municipalities are simply not set up to procure infrastructure through PPPs (Sundström, Citation2018).

Building long-term relationships and trust and reducing the focus on single transactions is a way for long-term investors to mitigate opportunistic and short-term incentives often present in PPPs (Henisz et al., Citation2012; Monk et al., Citation2017; Halland et al., Citation2018). In this approach, investors build a network which is based on mutual trust and a shared vision of creating sustainable infrastructure and co-operation. Some countries (for example the UK) have made regulatory changes so that pension funds can form ‘umbrella organizations’ under which they can collectively invest in infrastructure projects (Panayiotou & Medda, Citation2014).

Our research was motivated primarily by the two issues identified above: long-term investors’ need to find low-risk cash flow generating investments with lifespans exceeding several decades, and the public sector’s need for sustainable infrastructure assets creating systemic benefits. To resolve these issues, we propose a more relational approach in developing infrastructure assets, because it can bring the investors’ and the public sector’s interests closer to each other. Society is likely to benefit if private sector knowledge and ability to innovate is fully utilized. The prerequisite for this is getting stakeholders to work together to increase the value of the infrastructure projects and limiting short-sighted opportunism.

Our work is related to research on the governance of infrastructure projects (for example Levitt & Eriksson, Citation2016) and studies discussing the best ways for pension funds and other institutional investors to make infrastructure investments (for example Monk & Sharma, Citation2015; Vecchi et al., Citation2017; Halland et al., Citation2018). The purpose of this paper is to investigate the possibilities to adopt increased collaboration in an infrastructure project, between the public sector and investors in a country which has little history of PPPs, and has relied on traditional ways of public sector funded and owned infrastructure procurement. Our research question is two-fold; we first ask what the drivers for infrastructure owners and private investors are to engage in collaboration with each other and then proceed to identify challenges they need to overcome to get this co-operation a reality.

Our study answers calls for more empirical research on collaborative infrastructure investing (Levitt & Eriksson, Citation2016; Nowacki et al., Citation2016). We contribute to the literature by studying the prerequisites for collaboration among private investors as well as between these investors and the infrastructure owners in a market (Finland) which has, to date, relied on traditional public sector procurement of infrastructure (during the past 25 years only four roads have been procured through PPPs in Finland). Finland is also one of the few OECD countries without a PPP unit (Van den Hurk et al., Citation2015).

The Finnish pension funds invest in infrastructure through fund managers, and the investments are mostly in infrastructure assets abroad. In line with most other OECD countries, Finland has pressure to ramp up investments in its infrastructure and is, of course, motivated to maximize the value of these investments. As a small country with effective regulative institutions, Finland should be a good place for the collaborative and relational models to work (Henisz et al., Citation2012).

Our findings show that initially both the government with its institutions and the institutional investors were enthusiastic about increasing co-operation in developing infrastructure. Institutional investors welcomed the collaboration as a means towards new investment opportunities in infrastructure assets. They also saw value in having better control of the investments, including a bigger influence on the kinds of projects their funds were invested in. On the public sector side, the higher involvement of private investors in the projects was assumed to help in determining the value of the investments and to increase the value through innovative solutions. However, when proceeding to engage the two stakeholder groups in discussions with each other, some challenges emerged. The government officials looked at the projects from a very different angle compared to the institutional investors. The institutional investors focused on issues related to risk and return, and the government officials focused more on the benefits for society.

Private investors in infrastructure projects

PPPs have been widely studied by academics, industry, and government (Levitt & Eriksson, Citation2016). Both researchers and practitioners are quick to label a contract to produce infrastructure services involving private financing as a PPP, but there is a lot of variation of what kind of ‘partnership’ the last ‘P’ stands for (Hodge et al., Citation2018). Nevertheless, the assumption is that entrepreneurship, combined with a meaningful bundling of the various phases needed to produce the infrastructure service, should lead to better quality and lower costs to society (Monk et al., Citation2017).

Previous research on PPPs shows how private investors affect infrastructure projects. Consultants like McKinsey promote PPPs as advantageous, and institutions like the World Bank, Asian Development Bank and European Investment Bank appear to favour the PPP model. Most of the studies provided on these institutions’ websites of actual PPPs are more descriptive than evaluative. Mostly, the material is aimed to be of help to government officials, private investors and others involved in the planning and procurement of PPPs. However, there are some exceptions, for example a report about a water facility PPP in Shanghai reporting that the PPP was operating with 40% lower water treatment service fees (Asian Development Bank, Citation2010). However, the European Investment Bank (Citation2018) concludes that the reports provided by the public authorities are deficient for the purpose of reaching meaningful ex-post assessments of PPPs and therefore it cannot be stated that PPP projects would be better (or worse) than non-PPP projects.

Some of the academic literature contests the success of PPPs. One reason behind this debate is connected to how the ‘success’ of an infrastructure project is defined. Performance measurement is often connected with what is valued and what is not. Romero (Citation2015) illustrates this point with a hospital PPP in Lesotho; the project was criticized in one study because of its high public cost, whereas another study found it to be a success because of better treatment of patients. Success from the public’s point of view depends on what is valued and how that value is measured. The choice of measurement variables and their weightings in relation to each other, depend on public and political interests in the relevant countries. To add to these complications, the variables used, such as the safety of a train or the economic benefit an infrastructure project brings to a region, may only be possible to accurately measure over long time periods and, even then, it may be difficult to determine if the development is a consequence of the project or not (Ansar et al., Citation2016).

What is aimed for and how success is measured should be the tasks of the project owner (Winch & Leiringer, Citation2016), which for infrastructure projects often means a central government or municipalities. In PPPs, private sector entrepreneurship arguably leads to more efficiency in construction processes (Siemiatycki & Farooqi, Citation2012). At least in Australia and the UK, PPPs have been found to have better cost- and time-certainty compared to public procurement (Hellowell et al., Citation2015). On the other hand, Boardman et al. (Citation2016) argue that the findings suggesting PPPs are better on time and budget is due to the fact PPPs require more intensive planning and negotiation before start. Costs and time overruns may also be affected due to the private investors’ usual requirement that projects are delivered as turnkey projects (Jomo et al., Citation2016). High budget certainty can come at a cost. Studying 227 road projects in Europe, of which 65 were PPPs and the rest traditional procurement, Blanc-Brude et al. (Citation2006) found that the construction costs for PPPs are on average 24% higher compared to traditional procurement. Another issue is that overly rigid contracting at the beginning in environments with high uncertainty freezes design at an early stage and limits innovation (Davies et al., Citation2017). Relational contracting and governance can enhance the performance of infrastructure projects and curb short-sighted opportunism (Henisz et al., Citation2012; Davies et al., Citation2017).

To shift the advantage clearly in the favour of private involvement, it is crucial to get the entrepreneurship and innovativeness of the private partners to add value to the investment. For the value-added of the private sector’s innovativeness to be realized, it is important that changes and improvements to the project can be made continuously during the project starting from the early shaping phase. Much research sees the early stages of infrastructure projects (Miller et al., Citation2017), combined with good governance structures (Levitt & Eriksson, Citation2016; Winch & Leiringer, Citation2016) and relational contracting (Henisz et al., Citation2012), as very important determinants of the success of the projects. Good collaboration between central government, municipalities, investors and industry leaders is a central theme in infrastructure plans in Australia and Canada. Many other countries are looking at ways to increase private sector participation in infrastructure procurement (Vecchi et al., Citation2017).

Success from the private investors’ point of view is the return they get on their investment. When deals are treated as one-off transactions with the counterparties, returns can be sought by taking aggressive measures (Henisz et al., Citation2012). Fund managers hunting for the maximum performance fees may not be the best partners in charge on the investors’ side (Panayiotou & Medda, Citation2014; Monk et al., Citation2017). Thus, not surprisingly, the innovativeness and drive of the private sector have been shown to lead to cost and time savings but less often, if at all, do they enhance the value of investments through innovative design and new services (Boardman et al., Citation2016; Himmel & Siemiatycki, Citation2017). Fund managers are also more interested in acquiring existing assets than taking the time and risk to advance new greenfield projects (Panayiotou & Medda, Citation2014).

The long-term cash generating power of infrastructure assets makes them a good fit for pension funds. Pension funds and other long-term investors have traditionally invested in infrastructure assets through infrastructure funds which are managed by an asset manager. Many countries have taken action to open up infrastructure markets to be more directly accessible to pension funds (Panayiotou & Medda, Citation2014) and make the investments more ‘bankable’ for private investors (Hellowell et al., Citation2015; Vecchi et al., Citation2017). Lowering the thresholds for pension funds to invest directly in infrastructure may decrease the short-sightedness of PE type fund structures and too high leverage in the projects (Panayiotou & Medda, Citation2014). In exchange, direct involvement means that long-term investors put their reputations on the line so they will want more early stage planning and flexibility in the projects. It is important that investors and the other partners involved do not look at collaboration in terms of just one project but, instead, see it as a process which will contribute to multiple returns in the long run. Collaboration should be an ongoing process of networking and relationship building with partners all sharing the same goal; to develop infrastructure projects which create long-term benefits (Monk et al., Citation2017).

Initializing change in infrastructure procurement

Method and data collection

To date almost all infrastructure in Finland has been procured by the central government or municipalities and financed with taxpayers’ money. The Finnish pension funds have invested in infrastructure through fund managers and they have very limited, if any, direct holdings in infrastructure assets. The cultural homogeneity is relatively high and so is the level of trust among the Finnish population, Finland also has effective regulatory institutions which all should be good prerequisites for successful collaboration between infrastructure owners and investors (Henisz et al., Citation2012). Against this background, we set out to answer our research question—what drives infrastructure owners and investors towards closer collaboration and what challenges and lock-ins do these two parties have to overcome when making the co-operation a reality?

Our research method was clinical. Clinical/inquiry research (CIR) focuses on solving problems that are relevant for practitioners (Coghlan, Citation2009). In CIR the researcher focuses on helping the client and the researcher’s work should enable the client to explore, diagnose and act on the events when they emerge (Coghlan, Citation2009). The data generated is ‘real time’: created in the process of managing change and not only made up for the research project. The CIR method has been successfully applied to unstructured problems with wide and vague boundaries including many stakeholders (for example Eriksson et al., Citation2019). It is well suited to exploring the behaviour of investors in circumstances where real investment opportunities exist (Jones, Citation2015).

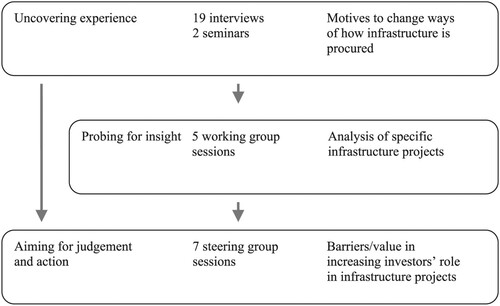

We divided our research according to the three stages of the collaborative process of clinical research laid out in Coghlan (Citation2009): uncovering experience, probing for insight, and aiming for judgement as well as action (see ). We tackled the first stage by conducting one-on-one semi-structured interviews with public officials and institutional investors and arranging two seminars where these actors discussed how traditional ways of infrastructure procurement could be changed. Based on the experiences gathered in the first stage, we set up working groups with representatives both from the infrastructure owner side and institutional investors. All of the meetings and seminars, and nearly all of the interviews, involved people with the power to influence how their organization would invest in infrastructure or how infrastructure should be procured (see ).

Table 1. Institutions and persons involved in the various stages of the research.

In the first stage, we conducted 19 one-on-one interviews with long-term investors, infrastructure owners and authorities overseeing infrastructure and then we arranged two seminars. Both seminars discussed how infrastructure investments might be increased and improved and were organized by the government of Finland and hosted by the minister of transport and communications. The first seminar had 14 participants, including government officials and senior managers of the major Finnish pension funds and other financial institutions. The second seminar had about 50 participants, including high-ranking government officials from the Nordic countries, institutional investors from Finland, Sweden and Norway and potential infrastructure project owners.

At this first stage of the research, we were aiming for what Coghlan (Citation2009) calls ‘pure inquiry’, as we learned how and why infrastructure is procured in the way it is. During this first step, we were also looking to recruit pension funds and suitable public officials to take part in the second stage of our research. Two of the pension funds agreed to take part in this second stage, along with the ministry of transport and communications. The work continued using specified investment cases which had the possibility to develop into actual investments. This work was done in a working group consisting of an analyst and a fund manager from the two participating pension funds. In the last step, we wanted the people responsible for infrastructure (or alternatives) at the two pension funds to form a steering group with the senior official from the ministry of transport and communications. The ultimate goal of the project was to set up a long-term collaborative structure able to handle a continuous deal flow, which previous research has been found to be advantageous for the partners (for example Ehlers, Citation2014). The data collection period extended over a period of close to three years (May 2017–March 2020).

Our real infrastructure cases consisted of two greenfield projects (a new tramline and a highway) and one project involving privatizing existing sea ports—see .

Table 2. The investment cases reviewed in the research process.

Three distinct topics became visible during the process of gathering the empirical material: the motives of the infrastructure owners to co-operate in the infrastructure space; the challenges the participants saw in increasing the direct involvement of pension funds in infrastructure projects; the value-added from collaboration. In this paper we have grouped these three topic areas into three phases: shaping, bid/execution and operation of the infrastructure asset.

Uncovering experience to engage in the collaboration

In the first round of interviews with institutional investors, we met five institutions (four pension funds and one bank). They all had considerable funds invested in infrastructure assets, and a balance sheet average (median) of EUR 40 billion (EUR 43 billion) in the end of 2017. The four pension funds with equity exposure to infrastructure had mainly used the fund model and had very limited, if any, direct investments in infrastructure assets. The bank providing debt financing to infrastructure projects did so directly. Apart from this infrastructure lender, the pension funds all had exposures to infrastructure below 10% of their AUM and they all said they wanted to increase this share.

Limited personnel resources is the main reason the pension funds invest in infrastructure via infrastructure funds operated through external asset managers. Two of the pension funds mentioned that they had considered expanding their infrastructure team but had decided against it as it would be too expensive compared to the expected deal flow.

Based on the interviews, a decision to invest or not can be divided into attributes related to the manager, the fund and the assets the fund is investing in. Fund type (closed end/open end), its strategy and fee structure and fee level appeared to be of less importance than the fund managers. The investors preferred funds with core infrastructure assets due to their low risk level and low correlation to the equity markets compared to value-added infrastructure assets.

On the whole, the fees paid to fund managers (typically a yearly 1% to 1.75% management fee on net asset value or invested amount plus a performance fee) was not an important driver to move away from the fund management model. In all, the reported returns of the investments run by fund managers (i.e. usually PE, infrastructure and venture capital) have been on a very high level during the past 10 years. The four biggest Finnish pension funds posted average annual returns for this ‘alternative’ asset class ranging from 11.9% to 13.2% for the years 2009–2018 (net of fees). For the pension funds, the reasons to increase collaboration in the infrastructure space appear related to avoiding problems and risks in the fund management model and the possibility to more directly influence the infrastructure investments.

The pension funds expressed concerns about information asymmetry between the pension fund and the fund manager. This information asymmetry can lead to the fund manager losing interest in working hard to increase the value of the fund, or it can lead to excessive risk taking. Both behaviours are forms of moral hazard and their likelihood increases if the fund manager estimates that their fund’s performance will not reach the rate of return (hurdle rate) which needs to be met to collect performance fees. Investment funds typically have pre-set return thresholds which need to be exceeded for fund managers to receive performance fees and, if the fund return performance is clearly below these thresholds, then the fund managers' motivation likely decreases and they may opt for high risk investments in a desperate attempt to reach the hurdle rate.

Wanting a bigger say in the way the investments are managed was not only related to controlling opportunism by the fund manager. The pension funds wanted to channel more funds into their domestic market but the international asset managers were mostly offering funds elsewhere. One of the pension funds specifically stated they wanted to ‘do good’ for their country. Sustainability and social responsibility issues were important.

Based on previous literature, investigating the option of direct investments into infrastructure could be used as leverage in negotiations with fund managers (Monk et al., Citation2017). However, this was not mentioned by any of the pension funds during the research. Perhaps this is because, by building up organizations which could decrease the relevance of the fund manager, the pension funds might also increase their risk of being left out of a fund managers’ best deals (Massi et al., Citation2018).

Before this research project there had been almost no discussion between the pension funds and government to directly channel pension investments into infrastructure assets in Finland. In the interviews and seminars conducted during the early stages of the research, both groups welcomed the idea of closer co-operation—see . Generally, collaboration between government and investors was viewed as increasing innovation in infrastructure investments, improving the procurement process and providing more financing options for government, and investment opportunities for investors. In the seminars, the government officials mentioned that measurement of the benefits of infrastructure projects would improve, whereas this was not mentioned by the investors.

Table 3. Uncovering the motives to increase investors’ stakes in infrastructure projects.

The institutional investors were confident that their co-operation could improve the procurement of the asset, resulting in a more valuable asset and/or a better price. The government officials also expected that the investors’ input in procurement would lead to a more valuable asset. Both sides appreciated that the co-operation would likely provide financing for the owners and investment possibilities for the investors.

Insights from case work with owners and investors

After the initial step of uncovering experience, the work continued with meetings between the stakeholders. In these meetings, the investment cases were prepared in a working group together with persons directly involved in analysing infrastructure investments (i.e. an analyst and a fund manager) so that they could be discussed in a steering group where the directors responsible for the pension funds’ infrastructure investments and one or more government representatives were present. At this stage, tensions between the government representatives and investors emerged. The government officials concentrated on improving the estimation and measurement of the benefits of an infrastructure project, whereas the institutional investors were more focused on securing a possible deal and, at an early stage, started to discuss return levels.

The government representative pointed out the importance of having an incentive structure which would maximize the value for society. Closely related to the incentive structure was the question of how to best estimate the cost and the benefits of the infrastructure asset. Both the government and city representatives supported the idea that they would subsidize the projects but also welcomed the idea that the end users would cover some of the costs of the services. To achieve a fair distribution of costs, it would be important that the benefits of the infrastructure projects could be identified and measured correctly.

Regarding financing, the government and city officials several times stated that private financing could make the financing of the investments less dependent on budget financing. The more flexible financing would mean they could seamlessly build large projects without dividing a project into smaller sub-projects to spread costs. Otherwise, the public officials did not value the private financing very highly as they assumed it would be costly in the long term.

In the discussions in the steering group, the institutional investors were very focused on getting a monetary return from the collaboration. There was clear evidence of a lack of trust between the pension funds on one side, and the government on the other. The pension funds were concerned about investing both time and money in preparing investment cases which would then be picked up by somebody else. This is a viable concern in the Finnish case, as currently no party can be guaranteed a contract without a tendering process. However, one of the two pension funds thought it was possible that the resources invested in building the relationship and collaboration would pay off in the long run, even in the case that some deals went to others.

Building trust was identified by all to be very important. In an interview with the representative for the government agency directly responsible for procuring transport infrastructure, this same issue came up regarding contractors. A continuous deal flow is also important to incentivize the contractors to give their best in innovating around new projects. The partners need to trust that, if they are left out on a particular deal, it will not be long before a new opportunity comes along.

Maybe due to a lack of trust that the government would be able to provide a continuous deal-flow, both institutional investors were very keen to discuss deal breakers. In the first steering group meeting, one of the pension fund representatives said that they expected to get an annual return on their investment in an SPV of 8% to 10%. This was further evidenced when going through calculations for the investment projects in a later meeting, when the pension fund representative said that the planned internal rate of return of 5.2% for the road project, in which the SPV would have both construction and operating risk, was too low. In connection to this, both pension fund investors were interested to discuss the capital structure and the risk allocation of the SPV at a very early stage. summarizes our findings from going through investment cases with the infrastructure owners and investors.

Table 4. Analysis of investment cases.

Aiming for judgement and action

Initially, the partners expressed their enthusiasm for collaborative ways of infrastructure investing and we were able to identify several likely advantages of the investment model during our data collection process. However, when the discussions turned to actual investment cases, including specifics on returns, risks and work to be carried out, some difficulties emerged. summarizes our findings, which we group under the three topics (motives, challenges and value proposition). In the uncovering experience phase, motives for collaboration were clear; however, during the casework, several challenges were seen. In the third column, we list the value propositions of increased collaboration between investors and the public infrastructure owner in a market which still heavily relies on traditional infrastructure procurement. Throughout the process, we identified several ways value could be added for both sides through the collaborative procurement of infrastructure.

Table 5. Identified motives, challenges and benefits of collaboration across different phases of infrastructure investment.

Conclusions

Increasing efforts to build relationships, trust and collaboration between the partners involved in infrastructure procurement mitigates opportunism and short-sightedness in infrastructure projects (for example Henisz et al., Citation2012; Panayiotou & Medda, Citation2014; Monk et al., Citation2017). We investigated the government’s and investors’ motives and challenges to engage in greater collaboration in the infrastructure space. We did this in the Finnish market, where institutional investors have been investing in infrastructure assets indirectly but have clearly expressed interest to increase their share of direct infrastructure investments.

Our results indicate that government and investors are enthusiastic about closer co-operation. Government partners expected private investors to improve estimates of the benefits of infrastructure investments. The public sector partners also welcomed the increased innovativeness that they expected the private sector to bring to the projects. The institutional investors, on the other hand, liked the idea of co-operation because they expected it would provide them with an increased deal-flow and they also looked forward to having a greater influence on projects. When we analysed real investment cases with the stakeholders, we detected some challenges for the collaboration. Both parties started to focus on the specific payoffs they or the infrastructure projects might get from a partnership. The public sector focus was very much on the estimation of benefits and the distribution of those benefits, whereas the investors were focused on their monetary return and their risks. In markets relying on traditional ways to procure infrastructure, it will take time to build trust and get used to the new ways of operating. Based on our study, other countries wishing to increase public–private financing initiatives should make sure that the partners involved have mutual goals for the collaboration and are ready to invest a lot of time and effort into the co-operation.

References

- Asian Development Bank. (2010). Sustainable urban development in the People’s Republic of China wastewater treatment: Case study of public–private partnerships (PPPs) in Shanghai. Urban Innovation Series. https://www.adb.org/publications/wastewater-treatment-case-study-public–private-partnerships-ppps-shanghai.

- Ansar, A., Flyvbjerg, B., Budzier, A., & Lunn, D. (2016). Does infrastructure investment lead to economic growth or economic fragility? Evidence from China. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 32(3), 360–390.

- Infrastructure Partnerships Australia. (2019). Australian infrastructure investment report. htpps://infrastructure.org.au/aus-infra-investment-report-2019.

- Blanc-Brude, F., Goldsmith, H., & Välilä, T. (2006). Ex ante construction costs in the European road sector: A comparison of public-private partnerships and traditional public procurement (Economic and Financial Report 2006/01). European Investment Bank, 1–49.

- Boardman, A. E., Siemiatycki, M., & Vining, A. E. (2016). The theory and evidence concerning public–private partnerships in Canada and elsewhere. SPP Research Papers, 9(12), 1–31.

- Coghlan, D. (2009). Toward a philosophy of clinical inquiry/research. Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 45(1), 106–121.

- Davies, A., Dodgson, M., Gann, D. M., & MacAulay, S. C. (2017). Five rules for managing large complex projects. MIT Sloan Management Review, 59(1), 73–77.

- Ehlers, T. (2014). Understanding the challenges for infrastructure finance. BIS working paper 454. https://www.bis.org/publ/work454.htm.

- Eriksson, K., Wikström, K., Hällström, M., & Levitt, R. E. (2019). Projects in the business ecosystem: The case of short sea shipping and logistics. Project Management Journal, 50(2), 195–207.

- European Investment Bank. (2018). Ex-post assessment of PPPs and how to better demonstrate outcomes. European PPP Expertise Centre. https://www.eib.org/en/publications/epec-ex-post-assessment-of-ppp.

- Fink, L. (2020). A fundamental reshaping of finance, larry fink’s 2020 letter to CEOs. Blackrock. https://www.blackrock.com/us/individual/larry-fink-ceo-letter.

- Hall, D. (2015). Why public–private partnerships don’t work—The many advantages of the public alternative. University of Greenwich. https://www.world-psi.org/en/publication-why-public–private-partnerships-dont-work.

- Halland, H., Dixon, A., In, S. Y., Monk, A., & Sharma, R. (2018). Governing blended finance—An institutional investor perspective. Stanford University. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3264922.

- Hellowell, M., Vecchi, V., & Caselli, S. (2015). Return of the state? An appraisal of policies to enhance access to credit for infrastructure-based PPPs. Public Money & Management, 35(1), 71–78.

- Henisz, W. J., Levitt, R. E., & Scott, W. R. (2012). Toward a unified theory of project governance: Economic, sociological and psychological supports for relational contracting. Engineering Project Organization Journal, 2(1), 37–55.

- Himmel, M., & Siemiatycki, M. (2017). Infrastructure public–private partnerships as drivers of innovation? Lessons from Ontario, Canada. Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space, 35(5), 746–764.

- Hodge, G., Greve, C., & Biygautane, M. (2018). Do PPP’s work? What and how have we been learning so far? Public Management Review, 20(8), 1105–1121.

- Inderst, G. (2014). Pension fund investment in infrastructure: Lessons from Australia and Canada. Rotman International Journal of Pension Management, 7(1), 40–48.

- Jones, A. W. (2015). Perceived barriers and policy solutions in clean infrastructure investment. Journal of Cleaner Production, 104(1), 297–304.

- Jomo, K. S., Chowdhury, A., Sharma, K., & Platz, D. (2016). Public-private partnerships and the 2030 agenda for sustainable development: Fit for purpose? DESA working paper 148. https://www.un.org/esa/desa/papers/2016/wp148_2016.pdf.

- Levitt, R. E., & Eriksson, K. (2016). Developing a governance model for PPP infrastructure service delivery based on lessons from Eastern Australia. Journal of Organization Design, 5(7), 1–8.

- Massi, M., Shandal, V., Harris, M., & Bellehumeur, K. (2018). A hands-on-role for private investors in private equity. Boston Consulting Group. https://www.bcg.com/publications/2018/hands-on-role-institutional-investors-private-equity.

- Miller, R., Lessard, D. R., & Sakhrani, V. (2017). Megaprojects as games of innovation. In B. Flyvbjerg (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of megaproject management (pp. 217–237). Oxford University Press.

- Monk, A., & Sharma, R. (2015). Capitalising on institutional co-investment platforms. Stanford University. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2641898.

- Monk, A., Sharma, R., & Sinclair, D. (2017). Reframing finance—New models of long-term investment management. Stanford University Press.

- Nowacki, C., Levitt, R. E., & Monk, A. (2016). Innovative financing and governance structures to solve the greenfield infrastructure gap: A case study of New South Wales, Australia. Stanford Global Projects Center, Stanford University. https://gpc.stanford.edu/publications/innovative-financing-and-governance-structures-solve-greenfield-infrastructure-gap-case.

- Panayiotou, A., & Medda, F. (2014). Attracting private sector participation in infrastructure investment: The UK case. Public Money & Management, 34(6), 425–431.

- Preqin. (2021). Preqin global infrastructure report. https://www.preqin.com/insights/global-reports/2021-preqin-global-infrastructure-report.

- Romero, M. J. (2015). What lies beneath? – A critical assessment of PPPs and their impact on sustainable development. A publication by Eurodad, European Network on Debt and Development. https://d3n8a8pro7vhmx.cloudfront.net/eurodad/pages/167/attachments/original/1587578891/A_critical_assessment_of_PPPs_and_their_impact_on_sustainable_development.pdf?1587578891.

- Siemiatycki, M., & Farooqi, N. (2012). Value for money and risk in public-private partnerships. Journal of the American Planning Association, 78(3), 286–299.

- Sundström, G. (2018). Framtidens universitetssjukhus—Beslut om Nya Karolinska Solna, Progress report 23, University of Stockholm. https://www.statsvet.su.se/polopoly_fs/1.374223.1519397339!/menu/standard/file/Framtidens%20universitetssjukhus%20-%20Beslut%20om%20Nya%20Karolinska%20Solna.pdf.

- Winch, G., & Leiringer, R. (2016). Owner project capabilities for infrastructure development: A review and development of the ‘strong owner’ concept. International Journal of Project Management, 34, 271–281.

- Van den Hurk, M., Brogaard, L., Lember, V., Petersen, O. H., & Witz, P. (2015). National varieties of public–private partnerships (PPPs): A comparative analysis of PPP-supporting units in 19 European countries. Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis: Research and Practice, 18(1), 1–20.

- Vecchi, V., Hellowell, M., della Croce, R., & Gatti, S. (2017). Government policies to enhance access to credit for infrastructure-based PPPs: An approach to classification and appraisal. Public Money & Management, 37(2), 133–140.