Abstract

IMPACT

The Austrian case emphasizes that Gender-Responsive Budgeting (GRB) is most successful if underpinned by legislation; however, overly detailed and rigorous guidelines might constrain advancements in the framework. This paper shows the ‘blank spots’ where GRB analyses were not undertaken, indicating the importance of formal checks and (independent) policy assessments to ensure meaningful analysis and planning of actions. Political support is crucial for diffusion; however, it is not a guarantee to fully exploit GRB’s potential. Finally, training strengthens the starting basis for implementation and needs to be extended in later periods of the implementation.

ABSTRACT

The paper studies the adoption of Gender-Responsive Budgeting (GRB), drawing on Rogers’ model for the diffusion of innovations, for two major elements of the Austrian approach to GRB—regulatory gender impact assessments and gender aspects in audits—through document analyses. The study analyses the significant impact of the implementation context (such as the constitutional anchoring, the preparation plan, capacity building and methodological guidelines) on the results of the implementation. The research demonstrates that ‘implementation’ and the ultimate ‘confirmation’ of GRB vary across governmental sectors and successful meaningful application require complementary implementation activities.

Introduction

Based on academic and lobbying work from advocates of Gender-Responsive Budgeting (GRB), countries on all continents have begun to adopt GRB (Galizzi & Siboni, Citation2016; IMF, Citation2016; Nolte et al., Citation2021; OECD, Citation2019). This development has been supported by international organizations: in particular, UN Women, the European Union and the Council of Europe (CoE, Citation2005; UN Women, Citation2019). However, GRB has only recently become an integral part of the agenda of international organizations; for instance, the United Nations defined ‘gender equality’ as one of its 17 Sustainable Development Goals (UN, Citation2019). This has resulted in formulating normative standards for good practices of GRB (IMF, Citation2016; OECD, Citation2019; PEFA, Citation2019). Since the field is still evolving, insights into the concrete adoption experience of countries are beneficial for the further development of the concepts and instruments.

GRB arose from the idea of applying gender mainstreaming to public budgets. Gender mainstreaming aims to promote gender equality in any activity (UN Women, Citation2019). Budgets are seen as powerful tools for implementing public policies and for ‘strategic gendering’ (Sassen, Citation2010, p. 29). Yet, traditional budgets have been criticized as being ‘gender-blind’ (Elson, Citation2000, p. 77), i.e. ignoring important differences in the lived experiences of women and men (O’Hagan, Citation2018) and crucial aspects of gender equality, such as the distribution of unpaid work (Elson, Citation2000; Marx, Citation2019). The Council of Europe’s widely used definition of GRB is that it entails a ‘gender-based assessment of budgets, incorporating a gender perspective at all levels of the budgetary process and restructuring revenues and expenditures’ in order to promote gender equality and accountability, to increase gender-responsive participation in the budget process and to advance women’s rights (CoE, Citation2005, p. 10; see also IMF, Citation2016).

A significant stream of the literature is normative, focusing on the rationale for, and how to, implement GRB (for example Nolte et al., Citation2021; PEFA, Citation2019). Here, the OECD, for example, defines three key areas for its success: a strong strategic environment, effective tools of implementation and a supporting environment (OECD, Citation2019). The IMF (Citation2016) highlights its integration into the public financial management system of a country, i.e. GRB is a ‘whole system approach’ (O’Hagan, Citation2018) that brings together gender, public finance and public financial management. However, the concrete implementation experiences and how the proposed abstract principles shape GRB results are still rarely studied in depth.

This paper analyses the implementation of GRB in Austria, which is considered an early adopter (IMF, Citation2016; Moser & Korać, Citation2020). Austria has received a lot of international attention for its approach in making GRB a constitutional principle within the scope of an overall federal budget law reform in 2013 (Steger, Citation2010). Despite a number of evaluations of this reform by international organizations and some academic studies of GRB (for example Moser & Korać, Citation2020; OECD, Citation2016), the outputs of the adoption of GRB have not been studied in depth. Also, in their study about the theorization of public sector management concepts in Austria, Höllerer et al. (Citation2020) found that GRB was not very enthusiastically taken up in the practitioner-driven discourse until 2012—in contrast to other public management concepts—which raises doubts about the actual implementation of GRB and leads to questions about whether GRB actually ‘work[s]’ in such a context (Steccolini, Citation2019, p. 379). This observation highlights the importance of exploring the implementation in more detail.

While recognizing the multidisciplinary nature of GRB (Elson, Citation2000) and the practical implication to foster collaboration between public financial management and gender practitioners for GRB implementation (IMF, Citation2017; OECD, Citation2016), the focus of our paper is on demonstrating how public financial management and organizational tools can be utilized for GRB purposes, such as clearer measurement of outcomes or improved embedding of gender analysis in public financial management processes. The paper addresses the research question of to what extent GRB has actually been implemented in the Austrian context and whether GRB has become a confirmed (political and administrative) commitment and a legitimate practice in Austria. Echoing recent calls in the literature to study GRB from an organization theory perspective (Galizzi & Siboni, Citation2016), we analyse this question through the lens of diffusion theory (Rogers, Citation2003).

Conceptual background: diffusion of GRB

Diffusion of innovations

Diffusion, as used within the scope of this research, refers to ‘the ‘spreading’ of something throughout a population’ (Lapsley & Wright, Citation2004, p. 356), whereas by ‘innovation’ we understand the ‘development of new accounting practices and techniques’ (Jackson & Lapsley, Citation2003, p. 359). GRB, for the purposes of this paper, is conceived as an accounting innovation that is translated ‘into tangible processes, resources, and institutional mechanisms’ (Chakraborty, Citation2014, p. 2) during adoption. Following extant research, we consider the diffusion of GRB to start with a process of translation in which the abstract concept developed by researchers and international organizations is introduced to a specific cultural country context (Drori et al., Citation2014; Wedlin & Sahlin, Citation2017), which results in concrete manifestations laying the groundwork to spread across different organizations. These can then be applied to specific policies or programmes. Such a translation is an ongoing social and path-dependent process in different arenas (Schneiberg & Clemens, Citation2006).

Diffusion stage 1—prior conditions

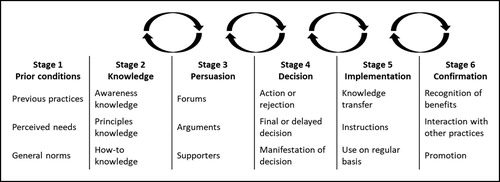

Rogers (Citation2003) develops a model which analytically separates different stages and which can be used to describe the context of GRB as an innovation until the stage when it is translated into a legitimate practice in a specific setting. We adapted this model to the GRB context. Rogers (Citation2003) describes the diffusion process as one occurring over time and consisting of five stages (from ‘knowledge’ to ‘confirmation’). An extension of this model, adding a sixth stage, ‘prior conditions’ (see ), as suggested by Ezzamel et al. (Citation2014), is appropriate as the progress of diffusion ‘is subject to favourable factors existing within its environment’ (Lapsley & Wright, Citation2004, p. 356). Indeed, GRB does not appear isolated but is highly interwoven with other gender equality challenges and policies. This may impact the receptiveness of any particular context to an innovation (Ezzamel et al., Citation2014). Specifically, ‘prior conditions’ are the prevalent practices and instruments that GRB ideas can build upon, for example existing analyses of gender equality or budgeting practices, perceived needs/gender gaps, or general norms, such as anti-discrimination laws.

Figure 1. A model for analysing the diffusion of innovations. Based on Rogers (Citation2003) and Ezzamel et al. (Citation2014).

Diffusion stage 2—knowledge

The second stage of Rogers’ model, ‘knowledge on reform innovations’, highlights the information-seeking and processing of the innovation (Rogers, Citation2003). Rogers distinguishes between three types of knowledge: ‘awareness’ knowledge (understanding of the existence of an innovation); ‘principles’ knowledge (such as the objectives of an innovation and why it works); and ‘how-to’ knowledge (tools, instruments, analytical methods, processes and structures). This process is strongly guided and influenced by knowledge already available in the pre-GRB discussion phase.

Diffusion stage 3—persuasion

‘Persuasion’ is the third stage in Rogers’ model. Establishing consensus about the need and rationale of GRB implementation is a social process involving multiple actors (on the political and administrative side, such as international and non-profit organizations), and both contested and complex. According to Rogers (Citation2003), a range of factors increase the likeliness of an innovation being accepted: its complexity, piloting of the innovation, the fit with the adopter’s existing values, the expected benefits from the innovation and the possibility of actually observing the results of the innovation (Rogers, Citation2003; see also Lapsley & Wright, Citation2004). This process takes place in different forums where the advocates and proponents exchange arguments about the local appropriateness of GRB.

Diffusion stage 4—decision

The first three stages lead to the implementation ‘decision’ of GRB in stage 4. From a formal point of view, this involves the adoption or rejection of a GRB law or another framework document (for example a strategic plan or a handbook). In practice, a decision can come in different forms, for example a temporary rejection, a decision for sequencing or a partial approval of GRB. The decision has to be made by a legitimate actor, which could be, for example the parliament, the cabinet or a responsible government minister. GRB frameworks can be approved in the form of constitutional or legal amendments, guidelines, handbooks or other manifestations of the decision. Stages 1–4 embrace the ‘translation’ aspect of GRB, in the sense of a modification of the more global, abstract ideas of GRB when attempting to make them resonate with the national context. More specifically, GRB ideas manifest in laws, tools, and organizational arrangements which guide the further application of the concept.

Diffusion stage 5—implementation

Once the decision to implement GRB has been made, the implementing organizations (in particular, ministries, agencies and NGOs), which are broader and partly different to the actors involved in decision-making, move to stage 5—‘implementation’. However, implementation is not a simple application of the legal or guidance material resulting from the decision, but also involves its active interpretation in the specific policy context (Pressman & Wildavsky, Citation1973). The shift from early adopters to a much wider array of adopters requires knowledge transfer activities and boundary-spanning (Polzer et al., Citation2020), and instructions to ensure a meaningful and informed application. However, at the same time organizational actors may seek to alter, modify or ‘reinvent’ the innovation, partly driven by the need to contextualize the approach for the specific circumstances (Pressman & Wildavsky, Citation1973).

Diffusion stage 6—confirmation

The final stage 6—‘confirmation’—is reached when GRB has become a legitimate practice beyond the formal decision and gains legitimacy through the implementation, where stakeholders start to recognize the benefits, promote the innovation and its meaningful application spreads throughout the public financial management system (Rogers, Citation2003). The question of how such enduring change can be achieved has also been discussed in existing public sector accounting research (for example Liguori & Steccolini, Citation2012).

Rogers (Citation2003) developed his model of stages with reference to other innovation studies (for example Von Hippel, Citation1988). The significance of the stages was confirmed by public sector accounting research (Ezzamel et al., Citation2014; Lapsley & Wright, Citation2004; Jackson & Lapsley, Citation2003). While recognizing their analytical value, we assume that in practice the stages are not clear-cut but serve more as an ex post concept for structuring and rationalizing developments. We also assume that developments within one stage can refer back to previous stages. For example, in the process of achieving consensus about what GRB entails (stage 3), perceived deficiencies can foster further activities in the area of knowledge generation (stage 2); or, unsurmountable challenges in the implementation (stage 5) might result in additional decision requirements (stage 4). Rather than a linear process, we therefore consider diffusion as a cyclical one where stages can be reached only temporarily.

Data, methods and analysis

This paper analyses the Austrian GRB model. We capture the diffusion of the GRB idea by analysing its manifestations within documents. In order to determine if a meaningful application of GRB takes place, we are especially interested in the different manifestations of its use by different actors, ranging from in-depth analysis and proposing policy responses to formalistic use.

The analysis of documents is a typical tool for our purposes (Schneiberg & Clemens, Citation2006). In order to understand GRB diffusion, we analysed two genres of texts, representing ex ante and ex post views of GRB (OECD, Citation2016; Steccolini, Citation2019):

Regulatory impact assessments (RIAs) where a gender assessment is an integral element for laws passed by parliament, including state contracts (N = 730).

Audit reports from the Austrian Court of Audit: Supreme Audit Institution Reports (SAIRs); (N = 339).

These genres represent major elements of the Austrian approach to GRB. In addition, the two genres were chosen because impact assessments are not a standard accounting tool, but have a strong policy focus and are at the core of GRB methodologies. Gender audits, in turn, have not been widely used despite their undoubted relevance to close the accountability cycle (IMF, Citation2016; OECD, Citation2016; PEFA, Citation2019). We analysed all RIAs and SAIRs issued between 2013 and 2018 at the federal government level (full sample). A (qualitative) coding strategy was followed, which was similar to what has been used in other diffusion studies (for example Rao et al., Citation2003).

All variables, with the exception of the last one, were coded in binary form. For each RIA and SAIR, we coded:

Gender topic: whether the scope of the law or the audit report might affect women or men differently, or if a gender bias existed (for example labour market policies might impact women and men differently as they work in different segments of the economy, or income tax legislation due to income disparities between women and men). The variable was coded independently of the intention of the RIA or SAIR to address the gender topic.

Gender gap: whether a gender gap or gender equality issue was clearly identified in an RIA or SAIR (for example references to the gender pay or pension gap, or imbalance of distribution of unpaid work) in order to identify those laws with supposedly significant gender relevance. Although gaps have been closed in areas such as general access to education and health, they are still significant, for example, regarding income and wealth distribution.

Gender analysis: whether an in-depth gender analysis was conducted in an RIA or SAIR (examples would be the analysis of the beneficiaries of social benefits or transfers, or the consumption behaviour of women and men in the context of the modification of tax laws). High-quality gender analyses in RIAs would normally use indicators such as the distribution of the budget by gender, in particular for social benefits, or the impact of taxes or tax benefits by gender. In SAIRs, these indicators would be used in combination with other gender-disaggregated indicators from the performance budget—for example the number of unemployed persons of different age groups, or users of health programmes—with additional indicators collected from the line ministries, such as beneficiaries and total amounts for different types of tax benefits, or visitors of cultural institutions.

Gender measures: in the RIAs or SAIRs, these refer to clearly proposed and measurable policy measures aiming to address gender gaps or to promote women, such as an increase in the representation of women in managerial positions in ministries and state-owned enterprises, or the creation of a fund providing loans for investment into housing with the main target group of lower-income women.

Responsible ministry for the RIAs (this was not possible for the SAIRs, as these do not always refer to a responsible ministry and some topics are cross-cutting, for example the determinants of the retirement age in a number of line ministries).

The coding of documents was done manually and the results were inputted into a spreadsheet. In order to increase the accuracy, reliability and validity of the coding (Trochim & Donnelly, Citation2006), the documents were reanalysed independently by a member of the research team. All cases of disagreement were revisited and resolved by the authors.

We used descriptive statistics in order to analyse frequencies and combinations. In particular, we are interested in whether increasing convergence of identified gender topics, gender analyses being carried out and proposed gender measures can be observed: over time (diachronic perspective); in different organizations (synchronic perspective); and in different text genres (RIAs and SAIRs). We assumed that a growing convergence of gender analyses and gender measures indicated a stronger meaningful utilization of GRB for policy-making, as GRB then supports evidence-based policy-making and encourages policy-making in line with the definition of GRB. We interpreted such a convergence as contributing to the ‘confirmation’ of the innovation as it is used in the intended way. In order to visualize results, Venn diagrams were drawn, using the Venn Diagram Plotter software (developed by the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory/US Department of Energy; https://omics.pnl.gov/software/venn-diagram-plotter).

The analysis was complemented with a number of interviews with representatives of the Federal Performance Management Office, the Ministry of Finance, line ministries, the Parliamentary Budget Office and other stakeholders. In addition, we drew on findings from observations of the parliamentary debates and secondary literature on GRB in Austria.

Results

Diffusion stage 1—prior conditions for GRB

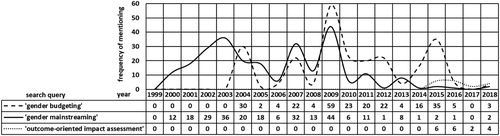

The context and steps that precede implementation set the scene for the implementation activities and guide the implementation. shows the discourse of GRB in the Austrian federal parliament between 1999 and 2018 (based on the Momentum Institute’s Parlagram database: https://www.momentum-institut.at/parlagram/); before 1999, none of the keywords (translated from German in the figure) were mentioned.

In 1979, gender equality was added to the ministerial level with the creation of a state secretariat for women and the passing of the General Equal Treatment Act. This was the beginning of gender equality measures—however, the term ‘gender equality’ was not used. In 1991, the creation of a ministry for women manifested the increased relevance of equal treatment for women. Additional incremental steps to promote gender equality (for example anti-violence, childcare facilities, family benefits, anti-discrimination and anti-sexual harassment) were subject to discussion in the parliamentary Gender Equality Committee, which mainly consisted of women (Mader, Citation2010). These developments peaked in a constitutional amendment including the principle of ‘gender equality’ in 1998.

Diffusion stage 2—knowledge about GRB

For GRB to be initiated, it is necessary for those involved to know and understand the concept, but factual knowledge alone is not sufficient. Rogers (Citation2003) different types of knowledge (awareness knowledge; principles knowledge; and how-to knowledge) are also needed. Mainly driven by civil society, a group of researchers and experts from various public institutions started with studying and promoting the concept of GRB and putting it into the Austrian context (Klatzer et al., Citation2018). A second source for gaining knowledge on GRB was the preparatory work on a major reform of the federal budget law, in which GRB was embedded, beginning from the early 2000s. The Ministry of Finance, as the main driver of the reform, identified and analysed selected international examples deemed to be relevant for improving the Austrian federal budget (Steger, Citation2010). With this, awareness knowledge was acquired and, in parallel, principles and how-to knowledge started to accumulate.

The abstract principles knowledge and decontextualized knowledge about country examples were useful inputs for different pilot activities on the municipal level to gain how-to knowledge. In addition, since the 2005 annual budget, gender-relevant information was included in budget documents as a supplementary section with a chapter on ‘Gender aspects of the budget’ for each ministry, comprising gender analyses of concrete (announced) measures (Klatzer et al., Citation2018). In parallel to knowledge generation activities, the lobbying process for GRB was started, which underlines the overlapping nature of the different stages.

Diffusion stage 3—persuasion to implement GRB

In 2000, the Austrian federal government committed itself to implementing a gender mainstreaming strategy and set up the Inter-Ministerial Working Group for Gender Mainstreaming/Gender Budgeting, chaired by the Minister of Women (Austrian Federal Chancellery, Citation2018). This group became an important forum to discuss GRB concepts, developments at the political level and experiences from pilot projects among civil servants of the different ministries.

In parallel, a watch group called ‘Gender and public finance’, formed by women from civil society, and research and public institutions in 2000, promoted GRB particularly at the political level. The group was concerned that the fiscal policy pursued by the government affected gender equality and women negatively (Klatzer et al., Citation2018). The group published papers (for example BEIGEWUM, Citation2002) and gave presentations on its research and ‘framed the concept in the Austrian context’ (ibid., p. 138). The upcoming comprehensive budget law reform covering performance and accrual budgeting ‘opened a window of opportunity for lobbying’ for formally anchoring GRB in the budget process and organic budget law (ibid., p. 139). The Ministry of Finance was in the lead, designing concepts for the federal budget law reform, and integrated GRB in the overall reform package.

In the parliamentary debate, the Social Democrats and the Green Party advocated strongly for GRB as a constitutional budget principle. Initial debates on budget reform were held in an informal parliamentary reform committee (Steger, Citation2010), discussing all reform elements with national and international experts. This forum brought different groups together, enabled an expert discourse and the further development of the concepts drafted by the Ministry of Finance, and laid the ground for its parliamentary approval. Critical voices and ideological differences were less prominent: the main reason being that GRB, as an integral part of performance budgeting, was embedded as just one of a range of other elements (including medium-term budgeting, accrual accounting and budgeting) of the budget law reform (Steger, Citation2010).

Diffusion stage 4—decision to implement GRB

The federal budget law reform that also enshrined the principle of gender equality as a budgeting principle in the constitution was unanimously approved by parliament in 2007. The first attempt to pass the budget reform had failed in 2006, mainly because of upcoming elections. Rushed decision-making would have put some positive votes at risk, which convinced the key players, including the Ministry of Finance, to delay the decision.

The principle of gender equality was put into effect starting from January 2009 (stage 1), and the key elements were included in the revision of the organic budget law (stage 2, approved in December 2009), which came into effect after January 2013 (Polzer & Seiwald, Citation2021). By then, GRB was formally being included in budget documents in the form of gender equality objectives (including activities and measurable performance indicators), person-related other performance indicators disaggregated by gender and annual reporting. More specifically, at least one gender objective had to be included in each of the (about 30) chapters of the federal budget (Polzer & Seiwald, Citation2021). However, most importantly for this research, the reform included mandatory ex ante RIAs, where gender aspects needed to be addressed (Austrian Federal Chancellery, Citation2018). According to the OECD (Citation2016), Austria is classified at needs-based gender budgeting where a ‘gender needs assessment’ identifying the gender inequalities and formulating the key priorities forms part of the budget process.

In the parliamentary discussion, GRB was most prominent (concerning references to the term ‘gender budgeting’ in parliamentary debates; see ) when the organic budget law was approved. The debate was combined with a discussion on gender mainstreaming, which had started already in 2000, but disappeared after this decision. Due to its constitutional status, even with a change of Austrian government, all subsequent governments were supposed to be committed to the GRB reform process (Steger, Citation2010).

Diffusion stage 5—implementation of GRB

All civil servants were assumed to be affected by the federal budget law reform and regarding RIAs, 600 civil servants had to be trained on how to interpret the regulations, to apply them and to use a relevant IT tool (Austrian Federal Chancellery, Citation2013). With this, issues of sensitization, staffing, training and preparing operational guidelines came to the forefront.

Phase 1: piloting and standard setting (2009–2012). In order to make ministries aware of GRB issues, pilot projects were formulated from 2009 onwards in each ministry. The projects were documented in the ‘strategy reports’ published alongside the medium-term budgets. The first projects did not follow a specific template and ranged from preparing a plan for promoting women, training staff for GRB, to the allocation of half of the budget for qualifying women (Austrian Ministry of Finance, Citation2009). During this phase, any initiatives referred to the staff of the public service, rather than to the population. The next strategy report included some gender equality projects in the priorities of the different budget chapters. Combining the two formats, the 2012 strategy report defined projects that had higher relevance and were presented in a more systematic and co-ordinated manner. In particular, results of some gender studies were presented to inform the measures proposed. With this, a learning curve can be observed.

In 2011, the Federal Chancellery set up a Performance Management Office that developed a range of regulations, guidelines and handbooks, and informed and trained ministries and agencies on GRB and RIAs to meet the new legal requirements (Austrian Federal Chancellery, Citation2013). While the Performance Management Office had a clear legal mandate and chosen a co-operative approach for working with line ministries which proved successful, there was still room for improvement for the performance information included, in particular, the quality of the indicators chosen.

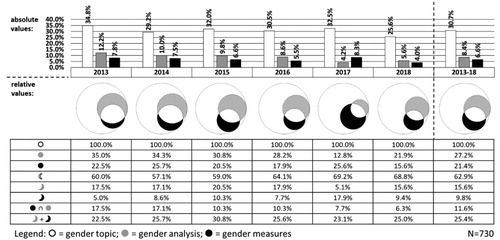

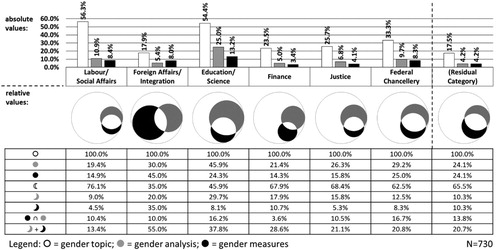

Phase 2: GRB goes ‘live’ (from 2013). In order to shed light on the question of to what extent GRB has actually spread, we plotted the variables gender topic (white), gender analysis (grey) and gender measures (black circles) for 2013 to 2018 on Venn diagrams for the RIAs and SAIRs (see ). A growing degree of overlapping of the circles in the figures could be interpreted as a ‘meaningful application’ of GRB. Building on previous research by Meyer (Citation2004), we differentiate between a diffusion over time (diachronic diffusion— and ) and a diffusion across different organizations and reports produced by these organizations (synchronic diffusion). For the latter purpose, groups the results for the RIAs by responsible ministry. Here, the six ministries with the highest number of laws with a gender topic were included. While RIAs are prescribed by law, there is a variety of potential options in how ministries can react to the demand (for example non-compliance, minimal analysis, justifications such as data availability). Also, interviewees confirmed the wide quality range of RIAs.

In terms of the diachronic diffusion, about one third (between 25.6% and 34.8%) of all RIAs included a gender topic (). Overall, a gender analysis was conducted in 27.2% of cases where a gender topic was identified. In 21.4% of cases where a gender topic was identified gender measures were proposed. The low number of conducted gender analyses in 2017 (12.2%) can be explained by the fact that in this year many laws were not initiated by the government (as is the usual case), but due to upcoming elections directly by Members of Parliament (for which RIAs are not required, resulting from a gap in the methodological framework). The observed pattern resonates well with previous research by Tolbert and Zucker (Citation1983, p. 22) that found that when new ‘procedures are required by the state, they diffuse rapidly and directly’. From a practical point of view, ex ante training seems to have provided a solid starting basis, but established networks and methodological support are still only used partially, as interviewees indicated.

More interesting, though, is to look at the overlapping part of the grey and black areas. It could be assumed that the convergence between gender analysis and gender measures increases over time, as administrations become more familiar with applying the concept. Following this reasoning, analyses would inform gender measures ex ante, or proposed policy measures would be analysed ex post. This is not backed by the data, however (the opposite is the case and the overlaps decrease from 17.5% in 2013 to 6.3% in 2018). The explanation seems to be twofold. First, in some cases, a conducted gender analysis might have indicated that measures are not necessary to be formulated, since no gender gap existed. On the other hand, this could point to an incomplete diffusion of GRB.

A significant proportion of gender-relevant laws were neither accompanied by a gender analysis nor by gender measures (62.9% over 2013–18—). This high number can be partly explained through the applied methodology in GRB, which defines a threshold for materiality, and laws below this threshold are exempt. In addition, in 2015, a simplified RIA methodology (the so-called ‘RIA light’) was introduced if no material impacts on gender equality were expected, whereby the Federal Performance Management Office and the Ministry of Finance had the role of gatekeepers.

An important question refers to the relevance of gender aspects in the eyes of the proponents of a law. The variable gender gap indicates whether a gender issue was mentioned in an RIA (for example a reference to a gender pay or pension gap, or an imbalance of distribution of unpaid work between genders). When analysing laws that actually identify a gender gap, we found that no gender analysis was conducted or no gender measures were proposed for only for 21.6% of the GRB-relevant laws. Moreover, the convergence between gender analysis and gender measures increased to 26.1% for these laws (versus 11.6% in ). Also, when looking deeper into the laws with a gender topic, but without a gender analysis conducted, we discovered that about 70% of the gender analyses referred to insignificant impacts, 10% explained why the initiatives did not have a gender impact and only 20% did not give any explanation. A lack of (meaningful) data was mentioned in some analyses but it was not a dominant argument for rejecting the RIA, which is in line with views of interviewees and experts that data gaps are closed, but the capacity to use the data is insufficient (Parliamentary Budget Office, Citation2019).

Regarding the synchronic diffusion across ministries (), patterns varied across sectors. The laws with gender topics were the highest in the Ministry for Labour and Social Affairs (56.3%) and the Ministry of Education and Science (43.4%). The convergence of gender analysis and gender measures was lowest in the Ministry of Finance at 3.6%—indicating a decoupling of analysis and policy-making. The highest convergence was observed in the Federal Chancellery (16.7%), followed by the Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs (10.4%). This result highlights different implementation practices and levels of achievement, and suggests that the ‘confirmation’ of GRB (stage 6) has not yet been reached. Interviewed gender experts related this to some civil servants lacking the necessary skills, but also to quality assurance mechanisms and clear responsibilities within a line ministry. However, such GRB-related capacities often remain an individual resource. One interviewee, for example, regretted a GRB expert’s job change, which resulted in a loss of capacity and a decline of the quality of the impact assessments in that ministry.

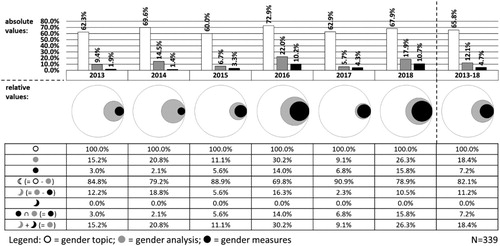

The number of gender topics in the SAIRs was about twice as high in comparison with the RIAs (between 60.0% and 72.9%—). While the coverage of a gender perspective in audits varied over the years between 9.1% and 30.2% (grey circles), there was no clear historic trend. However, a significant increase in the convergence of gender analysis and gender measures was observed, with just 3.0% in 2013 to 15.8% in 2018. Gender analyses (for example about imbalances regarding annual staff training hours) increasingly informed the development of concrete action plans. This is remarkable because there were no explicit rules or political agreements formulated (only the guiding constitutional principle). This finding emphasizes that implementation of GRB has different facets—with progress varying across sectors (administration versus auditing). It underlines the argument made by a number of our interviewees that the Court of Audit was committed to pursuing gender audits based on the constitutional principle; however, auditors had some discretion on whether to include a gender perspective in their audits.

Furthermore, an indicator of the synchronic diffusion of GRB is the extent to which the concept manifests in further federal government reporting. GRB aspects have been referred to in federal reports in the areas of culture (for example a ‘gender-incentive-programme’ to promote women in management positions in movie production companies), agriculture (for example women owning farms) and research (for example the number of women who were principal investigators in awarded research grants).

Finally, since 2016, the Inter-Ministerial Working Group for Gender Mainstreaming/Gender Budgeting has been publishing a blog about GRB implementation experiences in different public sector organizations in Austria and other countries, as well as expert opinions (http://blog.imag-gendermainstreaming.at/). In the absence of an overall gender equality strategy, several national action plans focusing on gender equality and/or diversity have been published, and a co-ordination procedure of bottom-up developed gender objectives has been implemented. In addition, a website was created by the Federal Chancellery to monitor the performance indicators (also related to GRB) which are formulated for the different budget chapters (https://www.wirkungsmonitoring.gv.at/).

Diffusion stage 6—confirmation of GRB?

In their recent study on the reform of the Austrian performance budgeting system, which incorporates GRB, Saliterer et al. (Citation2019, p. 13) found that there is ‘no indication of calls to roll back the system of performance-informed budgeting’. Klatzer and Stiegler (Citation2011, p. 6) already raised in the early stages of the GRB implementation the complex and ongoing nature of its confirmation as a legitimate practice:

In Austria, too, it is evident that the introduction and implementation of gender budgeting is a long-term process which, regardless of good legal foundations, still needs the constant commitment of the political and administrative leadership, as well as untiring efforts on the part of civil society groups in pursuit of the demand that government and administration implement equality.

Due to the gradual embedding of GRB into the budget system, with making use of pilot projects (Jorge et al., Citation2021), and the pre-existence of an Inter-Ministerial Working Group’ and a Watch Group, the process of change can be characterized as ‘incremental’ (Streeck & Thelen, Citation2005) and not abrupt, which is also backed by the fact that the compositions of the circles for the RIAs () did not change significantly over time. However, regarding the results of change, it is not yet clear if the reform will eventually lead to a ‘gradual transformation’ of existing budget practices (Streeck & Thelen, Citation2005). Confirmation, thus, may vary across different sectors of government—this is in line with findings from scholars who emphasize the importance of cultural change of GRB implementation (Steger, Citation2010). While some gender indicators have improved (such as the gender pay gap), and GRB has at least contributed to make the underlying gender gaps and issues transparent, the relationship is not necessarily causal, and would require further analysis in order to be used as an indication of confirmation.

Discussion and conclusion

We started this scholarly investigation with the question of how GRB in Austria has been translated, to what extent it has been implemented, and if the concept has been actually confirmed as a legitimate practice. The analysis of the international context showed that the actual implementation is guided by the starting conditions (in particular, the legal, institutional and methodological framework), but not determined by them. In the course of applying GRB principles, its confirmation as a legitimate practice may vary across different sectors of government and implementation goes beyond a simple application of rules. In some sectors, it might be a rather symbolic activity, whereas in others a transformation of practices towards an integrative practice emerges, and meaningful analyses inform legal initiatives and result in measures promoting gender equality.

Limitations and future research

As with all empirical research, this study has a number of limitations. First, assessing the impact of GRB in respect to actual gender equality outcomes, for example the reduction of gender gaps, is beyond the scope of this paper. Second, the study only analyses the Austrian case and approach with a (predominant) focus on documents, and possibilities for generalization are thus limited. Further avenues for analysis would thus be country comparisons, scrutinising other outputs and manifestations of GRB (such as budget documents and gender reports) and a more nuanced integration of the perspective of the users and producers of GRB material.

Lessons

The contributions of the paper are threefold. First, while there is a significant body of normative research, case studies and practical guidelines on GRB, there have been few empirical studies published about the actual implementation of the concept (Khalifa & Scarparo, Citation2020; Steccolini, Citation2019). This paper narrows this gap by developing and applying a conceptual model for analysing and disentangling the stages of the actual implementation of GRB, and to empirically scrutinize the adoption of two major elements of the Austrian approach to GRB, namely RIAs and SAIRs. The methodology allows the differentiation of the substance in GRB-related documents over time and across sectors to identify progress in the diffusion of the ideas of GRB, in the sense that GRB is meaningfully applied and informs and supports policy decision-making.

Second, this paper contributes to the literature with an application of the concepts of ‘diffusion’ and ‘translation’ to explain GRB as a legally prescribed practice. Translation better captures the emergence of a country-specific GRB model, whereas diffusion is more appropriate to understand how GRB is used and spread within the country context. We interpret the introduction of the ‘RIA light’ assessment (i.e. developing a contextualized version of the instrument) as an outcome of translating the instrument to the Austrian federal context (Wedlin & Sahlin, Citation2017), demonstrating that the diffusion of innovations is not a linear process (), but that developments happening at one stage can refer back to previous stages. In order to understand whether the practice diffuses, we introduce the notion of ‘meaningful application’, which we assume to observe if a high-quality gender analysis is combined with gender-responsive measures. We have also shown that ‘implementation’ and ‘confirmation’ are interdependent stages which are path-dependent, rather temporary in nature, and multifaceted (as evidenced by different manifestations and traces across/in sectors, organizations and documents).

Third, the research also attempts to understand what lessons can be learned for other GRB implementations from a practitioner perspective. The Austrian case emphasizes that GRB is most successful if underpinned by legislation (see also Quinn, Citation2017); however, this also draws some boundaries for its adoption, potentially restricting its success: overly detailed and rigorous guidelines might constrain advancements in the framework (Steccolini, Citation2019). In contrast, guidelines defining materiality criteria, when designed properly, can support focusing on relevant issues instead of applying the same methodology for each and every issue—thus using resources more efficiently. The case showed ‘blank spots’ where analyses were not undertaken, indicating the importance of formal checks and (independent) policy assessments to ensure meaningful analysis and planning of actions. Political support is crucial for diffusion; however, it is not a guarantee to fully exploit GRB’s potential. In the case of SAIRs, organizational and personal commitment, combined with a constitutional mandate, supported the gradual diffusion in audit reports. Finally, training strengthens the starting basis for implementation but both individual and organizational capacity building are also necessary in later periods of an implementation.

To conclude, GRB is one instrument towards striving for equality for social groups in public budgeting. The Austrian experience has demonstrated that meaningful application of GRB tools requires complementary implementation activities such as training, quality assurance and political support in the different forums and genres.

Disclaimer and acknowledgements

This paper embodies the views of the authors and does not represent the views or policy of the Austrian Parliamentary Budget Office. The data for this study was partly collected as part of a capstone project at WU Vienna. We thank Benjamin Cibulka, Sandra Crepaz, Sarah Anna Fernbach, Isabel Hartlieb, Katharina Jesse, Lisa Präauer and Matthias Wukitsch. The paper was awarded the ‘Carlo Masini Award 2020’ (best paper of the Academy of Management Annual Meeting from the Public and Non-Profit Division). We are very grateful to the selection committee and Bocconi University, the sponsor. We also thank guest co-editor Giovanna Galizzi and the two anonymous Public Money & Management reviewers for their thoughtful comments. As always, all remaining errors are entirely our own.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

References

- Austrian Federal Chancellery. (2013). Bericht über die wirkungsorientierte Folgenabschätzung. Federal Chancellery.

- Austrian Federal Chancellery. (2018). Gender equality in Austria. milestones, successes and challenges. Federal Chancellery.

- Austrian Ministry of Finance. (2009). Strategiebericht zum Bundesfinanzrahmengesetz 2009-2013. Austrian Ministry of Finance.

- BEIGEWUM. (2002). Frauen macht Budgets. Staatsfinanzen aus Geschlechterperspektive. Mandelbaum.

- Berger, P., & Luckmann, T. (1966). The social construction of reality. Anchor Books.

- Chakraborty, L. (2014). Gender-responsive budgeting as fiscal innovations. Levy Economics Institute of Bard College.

- CoE. (2005). Gender budgeting. Council of Europe.

- Drori, G., Höllerer, M., & Walgenbach, P. (2014). The glocalization of organization and management. In G. Drori, M. Höllerer, & P. Walgenbach (Eds.), Global themes and local variations in organization and management. perspectives on glocalization (pp. 3–23). Routledge.

- Elson, D. (2000). Gender at the macroeconomic level. In J. Cook, J. Roberts, & G. Waylen (Eds.), Towards a gendered political economy (pp. 77–97). Macmillan.

- Ezzamel, M., Hyndman, N., Johnsen, A., & Lapsley, I. (2014). Reforming central government: An evaluation of an accounting innovation. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 25(4/5), 409–422. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpa.2013.05.006

- Galizzi, G., & Siboni, B. (2016). Positive action plans in Italian universities: Does gender really matter? Meditari Accountancy Research, 24(2), 246–268.

- Höllerer, M. A., Jancsary, D., Barberio, V., & Meyer, R. E. (2020). The interlinking theorization of management concepts. Organization Studies, 41(9), 1284–1310.

- IMF. (2016). Gender budgeting: Fiscal context and current outcomes. IMF.

- IMF. (2017). Gender budgeting in G7 countries. IMF.

- Jackson, A., & Lapsley, I. (2003). The diffusion of accounting practices in the new ‘managerial’ public sector. International Journal of Public Sector Management, 16(5), 359–372. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1108/09513550310489304

- Jorge, S., Nogueira, S., & Ribeiro, N. (2021). The institutionalization of public sector accounting reforms: The role of pilot entities. Journal of Public Budgeting, Accounting & Financial Management, 33(2), 114–137. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1108/JPBAFM-08-2019-0125

- Khalifa, R., & Scarparo, S. (2020). Gender responsive budgeting: A tool for gender equality. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpa.2020.102183

- Klatzer, E., Brait, R., & Schlager, C. (2018). The case of Austria: Reflections on strengthening the potential of gender budgeting for substantial change. In A. O’Hagan, & E. Klatzer (Eds.), Gender budgeting in Europe (pp. 137–157). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Klatzer, E., & Stiegler, B. (2011). Gender budgeting—an equality policy strategy. Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung Shanghai Office.

- Lapsley, I., & Wright, E. (2004). The diffusion of management accounting innovations in the public sector: A research agenda. Management Accounting Research, 15(3), 355–374. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mar.2003.12.007

- Liguori, M., & Steccolini, I. (2012). Accounting change: Explaining the outcomes, interpreting the process. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 25(1), 27–70. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1108/09513571211191743

- Mader, K. (2010). Gender Budgeting: Geschlechtergerechte gestaltung von Wirtschaftspolitik. Wirtschaft und Politik, 33, 44–49.

- Marx, U. (2019). Accounting for equality: Gender budgeting and moderate feminism. Gender, Work & Organization, 26(8), 1176–1190. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.12307

- Meyer, R. (2004). Globale Managementkonzepte und lokaler Kontext. Organisationale Wertorientierung im österreichischen öffentlichen Diskurs. WUV Universitätsverlag.

- Moser, B., & Korać, S. (2020). Introducing gender perspectives in the budgetary process at the central government level. International Journal of Public Administration, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/01900692.2020.1755683

- Nolte, I., Polzer, T., & Seiwald, J. (2021). Gender budgeting in emerging economies–a systematic literature review and research agenda. Journal of Accounting in Emerging Economies, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1108/JAEE-03-2020-0047

- OECD. (2016). Gender budgeting in OECD countries. OECD.

- OECD. (2019). Designing and implementing gender budgeting. A path to action. OECD.

- O’Hagan, A. (2018). Conceptual and institutional origins of gender budgeting. In A. O’Hagan, & E. Klatzer (Eds.), Gender budgeting in Europe (pp. 19–42). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Parliamentary Budget Office. (2019). Gender Budgeting. Fortschritte und Herausforderung. Austrian Parliament.

- PEFA. (2019). Supplementary framework for assessing gender responsive budgeting. PEFA.

- Polzer, T., Gårseth-Nesbakk, L., & Adhikari, P. (2020). ‘Does your walk match your talk?’ Analyzing IPSASs diffusion in developing and developed countries. International Journal of Public Sector Management, 33(2/3), 117–139. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPSM-03-2019-0071

- Polzer, T., & Seiwald, J. (2021). Outcome orientation in Austria: How far can late adopters move? In Z. Hoque (Ed.), Public sector reform and performance management in developed economies (pp. 119–145). Routledge.

- Pressman, J., & Wildavsky, A. (1973). Implementation: How great expectations in Washington are dashed in Oakland. University of California Press.

- Quinn, S. (2017). Gender budgeting in Europe: What can we learn from best practice? Administration, 65(3), 101–121. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1515/admin-2017-0026

- Rao, H., Monin, P., & Durand, R. (2003). Institutional change in Toque Ville: Nouvelle cuisine as an identity movement in French gastronomy. American Journal of Sociology, 108(4), 795–843. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1086/367917

- Rogers, E. M. (2003). Diffusion of innovations. Free Press.

- Saliterer, I., Korać, S., Moser, B., & Rondo-Brovetto, P. (2019). How politicians use performance information in a budgetary context. Public Administration, 97(4), 829–844. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/padm.12604

- Sassen, S. (2010). Strategic gendering: One factor in the constituting of novel political economies. In S. Chant (Ed.), International handbook of gender and poverty: Concepts, research, policy (pp. 522–527). Edward Elgar.

- Schneiberg, M., & Clemens, E. (2006). The typical tools for the job: Research strategies in institutional analysis. Sociological Theory, 24(3), 195–227. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9558.2006.00288.x

- Steccolini, I. (2019). New development: Gender (responsive) budgeting—a reflection on critical issues and future challenges. Public Money & Management, 39(5), 379–383.

- Steger, G. (2010). Austria’s budget reform: How to create consensus for a decisive change of fiscal rules. OECD Journal on Budgeting, 10(1), 7–20. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1787/budget-10-5kmh5hcrx924

- Streeck, W., & Thelen, K. (2005). Introduction: Institutional change in advanced political economies. In W. Streeck, & K. Thelen (Eds.), Beyond continuity: Explorations in the dynamics of advanced political economies (pp. 3–39). OUP.

- Tolbert, P., & Zucker, L. (1983). Institutional sources of change in the formal structure of organizations. Administrative Science Quarterly, 28(1), 22–39. DOI: https://doi.org/10.2307/2392383

- Trochim, W., & Donnelly, J. (2006). The research methods knowledge base. Atomic Dog Publishing.

- UN Women. (2019). Gender equality as an accelerator for achieving the Sustainable development Goals. UNDW and UN Women.

- Von Hippel, E. (1988). The sources of innovation. OUP.

- Wedlin, L., & Sahlin, K. (2017). The imitation and translation of management ideas. In R. Greenwood, C. Oliver, T. Lawrence, & R. Meyer (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of organizational institutionalism (pp. 102–127). Sage.