Abstract

IMPACT

The authors suggest that the governance of public value will contribute to highlighting important qualitative aspects necessary for the successful implementation of gender mainstreaming. The success of work with the strategy of gender equality is dependent on which management accounting system that is in use. A good example is to use gender-awareness as an input and to go beyond short-term assessment of output into long-term valuation of outcomes. To avoid ending up with irrelevant output measures, gender-aware planning and assessment of qualitative processes and outcomes is required.

ABSTRACT

Gender mainstreaming has been hampered by the governance guides of New Public Management (NPM). Public Value Management is an alternative approach that can be interpreted as a concept for management accounting that meets the challenges that NPM was never able to handle. This paper discusses the case of gender mainstreaming in the Swedish transport sector.

Introduction

Gender mainstreaming, as a strategy for achieving gender equality policy goals, has been a guiding priority since the 1990s and the Swedish government still believes it is needed:

Since equality between women and men is created where ordinary decisions are made, resources are allocated and norms are created, the gender perspective must be included in daily work. The strategy [of gender mainstreaming] has evolved to counteract the tendency for gender equality issues to end up being neglected or marginalized. (Swedish government website, May Citation2021; authors’ translation.)

From a gender science perspective, the dilemma is evident when an NPM-influenced management accounting system indicates that a gender equality policy goal is fulfilled—even if only minor steps towards a more equal gender distribution have been taken. Rather than an achievement, these are signs of a gender-blind ‘measurability trap’ that closes when goals for gender equality are considered to be fulfilled with results that only indicate statistics on how many women and men are represented in different situations. Even with the quota of 40/60, which is considered to be an equal distribution, counting female and male bodies is not enough to understand the power relationships involved in gender equality. Power is not a unique quantitative phenomenon: it involves several qualities, which we will come back to later. The measurability trap appeared in a longitudinal research study focusing on the accounting of the transport policy goal of a gender-equal transport system in the early 2000s (Wittbom, Citation2015). This trap was found to be set up by the technocratic culture that made quantitative measures the most credible way to monitor any results.

In the follow-up of a gender-equal transport system, measurements of the quotas of women who participated in different types of meetings were perceived as concrete results. No qualitative gender analysis was made that could have disclosed gendered inequalities in agenda-setting and power imbalances regarding whose experiences were considered. With the MBO model, including specific performance targets, it was also sufficient to report only a minor increase in the quota of women to signal goal fulfilment, for example, to go from 23 to 25% of women attending. Despite the fact that female representation was far below 40%, which is usually referred to as the lower limit for an equal gender distribution, it was correct from a gender-blind perspective to state the goal as fulfilled. This comes from the practice of using the SMART criteria (specific, measurable, accepted, realistic and time-set) for target-setting, which prescribes that any realistic increase is enough.

In this paper we discuss how dominant ideas of management accounting minimize the analysis of gendered power relationships (Connell, Citation2002). With an interpretive approach (Alvesson & Sköldberg, Citation2018), a gender theoretical perspective is applied to the accounting of gender mainstreaming. Gender issues in transportation have been highlighted in many countries—see, for example, the work on transport connectivity out of a gender perspective in the International Transport Forum (ITF, Citation2019). NPM has been implemented in many countries all over the globe (Funck & Karlsson, Citation2019) but without a gender focus. The empirical case in this paper is the Swedish Transport Administration (STA), a government agency that was established in Citation2010, charged with executing the planning of infrastructure for all transport modes—road, rail, air and sea.

STA adopted the vision ‘Getting everyone where they are going smoothly, ecologically and safely’, supplemented by the mission ‘We are societal developers who develop and maintain smart infrastructure every day. We do this together with others to make life easier throughout Sweden’ (STA’s Annual Report, Citation2010, p. 7; authors’ translation).

Taking on the role of a societal developer means adopting a broader view of the mission compared to the earlier transport agencies’ identification as societal builders. Building something is about constructing and assembling, while developing is about changing characteristics. Therefore, the new mission can be interpreted as going from a technocratic constructing of transport systems to a more socially oriented approach to transportation.

The question in this paper is how the societal development ambition can contribute to the work of gender mainstreaming from a gender-aware governance perspective: How can the measurability trap be avoided with new forms of governance and management accounting? The purpose is to discuss an alternative form of governance—beyond NPM—that can open up to such gender-aware accounting.

The next section deals with theories that enable an analytical gender perspective on the governance of gender mainstreaming. The following sections are based on close readings of documents issued by the Swedish government and its agencies, focusing on the accounting of a gender-equal transport system. In the final sections we discuss the contribution of including accounting issues in feminist research on gender mainstreaming as a strategy.

Gender equality and gender theory

The status of gender equality in an empirical context can be assessed on the basis of at least four different theoretical aspects. One of these four aspects is the mapping of women and men using quantitative methods, which makes visible gendered patterns regarding tasks and hierarchical positions (Acker, Citation1992; Wahl, Citation2003). However, such surveys do not explain the existence of horizontal and vertical gender segregation. They do disclose the effects of ‘homosociality’, i.e. mainly when men chose to co-operate with men. But the statistical mapping of men and women neither give explanations to homosociality, nor to the formation of glass walls and glass ceilings (Kanter, Citation1977). To understand why certain tasks and positions are mainly occupied by men and others mainly by women, we must consider three different qualitative aspects concerning power relations. They are about symbols and discourses that affect gender segregation, interaction patterns linked to gender—for example in the form of domination techniques—and the individual’s own perception of what is expected of them based on their gender. Together these aspects form what Connell (Citation2002) defines as ‘gender regimes’ and Acker (Citation2009) discusses as ‘inequality regimes’.

Gender-aware assessment of equality thus requires both quantitative and qualitative data. This also means that gender equality cannot prevail solely because of an equal distribution of men and women (Rönnblom, Citation2002). Other factors that must be considered are where the interpretive prerogative is situated, as well as whose and which experiences are impactful. Prevailing gender-marked structures and cultures need to be highlighted in each empirical context (Wahl et al., Citation2018). Relevant knowledge and a genuine will to learn are both indispensable resources for such a qualitative gender analysis to be carried out (Callerstig, Citation2011). But gender research shows countless resistance strategies against gender equality work (Pincus, Citation2002; Lindholm, Citation2012; Linghag et al., Citation2016).

Gender mainstreaming is often handled in temporary projects decoupled from the organizational core operations, or by a gender equality committee without access to key forums for decision-making. For legitimacy reasons, gender equality ambitions tend to survive as long as they stay marginalized from the core business. The same applies when gender equality work is assimilated into the current order without changing the content of the operations. But the desirable transformative effect, when the core business adopts gender equality standards, demands a system change. Lacking such a transformation of an unequal structure and culture, persons of the underrepresented sex tend to either assimilate into the prevailing order or become marginalized (Häyrén, Citation2016; Squires, Citation2005).

Given that gender relations are neither stable nor predictable, they need to be empirically defined in each context. This also means that ignorance is a tool for resistance to gender mainstreaming; the tools for a gender-aware analysis need to be available (Pincus, Citation2002). ‘In order to trace the effects of mainly soft, informal, and cognitive instruments like gender mainstreaming, analysis cannot be reduced to a focus on traditional, vertical and regulatory change’, Jacquot (Citation2010, p. 132) writes and argues that this characteristic also explains how change by gender mainstreaming differs from many other types of change processes. But, even if gender mainstreaming in many ways is complex and difficult, it still requires the ordinary tools for successful organizational change: sufficient resources, inclusion in the normal management processes and the support of higher management (Callerstig, Citation2011).

The support of higher management is indispensable for the organizational capacity to implement transforming processes. This support needs to be sustainable, given that a gender-aware analysis reveals a malfunctioning management accounting system. Management accounting education textbooks are based on the assumption that models for accounting are gender neutral, and are in no way marked by gender. Together with earlier feminist researchers, Holmblad Brunsson (Citation2005) contributes, in her book on Management Control, a good understanding that this is not true:

Accounting has traditionally been handled by women. But that does not mean that the actual accounts are expressions of particularly female approaches. On the contrary, the whole phenomenon can be considered typically male (Cooper, Citation1992; Hines, Citation1992). It is men who have wanted to gain control through hierarchies and other expressions of order. Men designed the requirements for corporate financial accounting so that it looks as if order exists. You get the impression that everything is included. In fact, large and important areas, which have been difficult to measure, have been left out of the accounts. (Holmblad Brunsson, Citation2005, p. 76; authors’ translation.)

Effectiveness in the public sector

NPM (Hood, Citation1995) won ground when politicians lost confidence in centralized budgetary control and taxpayers called for efficiency. Efficiency and effectiveness became keywords and management accounting models were inspired by the private sector’s way of working with cost control and profitability (Modell & Grönlund, Citation2006). At the same time, citizens started to be constructed as ‘customers’ of public administration (Modell & Wiesel, Citation2009). Customer orientation was meant to enhance the quality of public services while spending less money. In the transport agencies, customer groups were defined without any gender perspective, which is why customer orientation did not contribute to any increased gender mainstreaming in the transport sector (Wittbom, Citation2011).

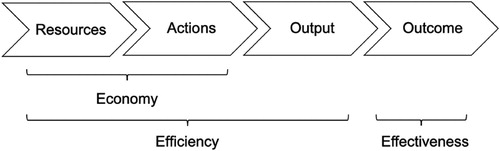

The concept of the 3Es—economy, efficiency and effectiveness—can be interpreted with the resource transformation chain emanating from the input/output model in economics. Management accounting theories allow us to open the ‘black box’ that, in the original model, lies between input (resources) and output/outcome (results): see .

This resource transformation chain is often used to analyse organizational operations from a financial perspective. With the MBO model, measurable targets are set for each part of the resource transformation chain; measures that can be related to one another using key performance indicators. By measuring the actions in relation to the available resources, resource utilization becomes the first E: economy. The results are divided into two parts:

Performance by output, indicating what the actions led to.

The effects these delivered performances led to in terms of outcome, especially outside of the organization’s boundaries.

Measures of output in relation to measures of resources were used in indicators of productivity, i.e. efficiency. Economy and efficiency point inwards, into the organization. However, they do not say anything about whether the organization has made valuable deliveries. To gain control over effectiveness, the output needs to be valued from an external perspective.

Effectiveness is difficult to account for, partly due to the fact that effects often occur long after delivery, and partly because there is seldom a clear relationship between cause and effect. Another difficulty in measuring effectiveness from an individual organization’s perspective is that outcomes are effects caused by many actors, and accounting rules prohibit one organization from showing outcomes other than those caused by themselves. The difficulties in adequately accounting for effectiveness led, under the pressure of NPM, to a focus on output.

Another problem with the resource transformation chain is that it does not take into account what is specific to the public sector. One aspect is that money is a means of implementing political decisions; it is not an end in itself. Public agencies cannot set market prices of their deliveries and make money. Nor can an agency choose its customers. In particular, there are clear demands for equity that must always be taken into account in the public sector: such requirements are lacking in the private sector (Sharp & Broomhill, Citation2002), and equity cannot be understood according to the same logic as the 3 Es (Bovaird et al., Citation1988). Equity as the fourth E, in this case gender equality, is instead supposed to permeate—mainstream—the entire chain: gender-equal distribution of resources, actions done in the vein of gender mainstreaming, output should add to gender equality so that the outcomes become gender equal. When the NPM-influenced management accounting systems are practiced in the public sector without taking into account the fourth E, the normal form of management accounting counteracts gender mainstreaming. In addition, there are several strategies of resistance to gender mainstreaming at play—active, passive or very subtle forms of resistance, intended or unintended (Pincus, Citation2002).

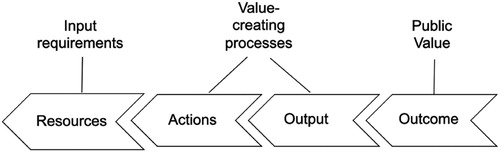

The requisites of quantitative measurements in MBO have brought output and productivity into focus. This means that the resource transformation chain is followed from the inside out, which neither supports innovation nor knowledge development, since it is good enough simply to use available resources in a cost-effective way. A reverse model gives an outside-in perspective based on desired outcomes. Effectiveness is focused by asking questions as to whether the outputs contribute to the intended outcomes: Is the organization working with the most suitable resources and actions to achieve politically set objectives and creating public value? The resource transformation chain is transformed into a value creation chain: see .

The desire for governance beyond NPM

It has been shown that classic public sector ideals, such as the rule of law and equity, have been overshadowed by management accounting. This can be explained by goal conflicts between equity and cost-efficiency where a transparent and stable bureaucracy may give way to flexible solutions that are perceived to be efficient (Aberbach & Christensen, Citation2005). Since 2015, the Swedish government has openly questioned its own governance, which is permeated by the NPM concept’s quantitative measurability requirements. The insight that it is not enough to measure quantitatively is evident from the government’s way of addressing ‘real power’ in gender-equal power relations:

An equal distribution of power and influence between women and men in all sectors of society is, of course, not a guarantee that real power is distributed equally between the sexes, but it is a crucial prerequisite for the qualitative aspects of power relationships to be changed towards gender equality.

(https://www.government.se/government-policy/gender equality: More about the policy goals of gender equality; authors’ translation.)

The project will contribute to a clear, trust-based management that contributes to the tax-financed welfare services being demand-driven, maintaining high and comparable quality, as well as being equal, gender equal and accessible. (Dir. 2016:51, Tillit i styrningen. Ministry of Finance; authors’ translation)

Future research will show what developed governance means for gender mainstreaming. The demand-driven services required by the directive above are intended to be governed in a new way, beyond NPM. As the criticism of NPM has intensified, interest in Public Value Management (PVM) has increased (Greve, Citation2015; Thomson, Citation2017). PVM was presented by Moore (Citation1995) in parallel with Hood (Citation1995) when launching NPM, but it did not receive the same attention at the time.

PVM versus NPM

PVM is a theoretical concept based on three strategic questions to be asked by any government administration:

Is it valuable for the public?

Is it legitimate and politically supported?

Do we have the operational capacity?

The discussion on public value is central in the PVM literature. Moore (Citation2013) and Rutgers (Citation2015) claim that there are no obvious facts to assume; what constitutes public value is problematized by the three strategic questions. This means that a well-functioning administration needs to evaluate a phenomenon from several perspectives, to discuss public values with various stakeholders, not just from the perspective of the present stakeholders; the conceivable interests of future generations must also be assessed.

Two different strands emerge in the literature on PVM. One is that value and benefit can be assessed by aggregating the short-term perceptions of individual citizens, while the other is based on long-term value and benefits for citizens as a whole (Benington & Moore, Citation2011). Starting from individuals’ desires is in line with NPM and derives from the private sector’s customer orientation, where the customers’ specific demands may define the deliveries, which has proved problematic for politically controlled organizations where democracy and justice must permeate enforcement (Aberbach & Christensen, Citation2005). The second approach is in line with PVM, which is based on networks of actors with broader and more long-term public interests (Thomson, Citation2017). With PVM, employees in the authorities can gain more confidence by knowing more about what society needs in a collective sense. Trust can be achieved by interacting with the citizens in a democratic approach (Benington & Moore, Citation2011; Brown, Citation2009; Prebble, Citation2012).

Although MBO is here to stay, decreasing NPM and enforcing PVM could significantly contribute to creating governance that, when it comes to accounting for overall policy objectives, better matches the special conditions prevailing in the public sector. The resource transformation chain is turned into value creation by starting from politically and democratically determined public values. To be able to discuss what such a kind of governance can mean for gender mainstreaming, the following sections present an example from the field of transport policy.

The policy goal of a gender-equal transport system

The Council of Gender Equality in Transport and IT stated that the transport sector was male dominated and that the transport system functioned in an unequal way (SOU Citation2001:44). The transport agencies’ core operations were to be gender mainstreamed, enabling the delivery of a gender-equal transport system:

A transport system that is managed by and serves the interests of women and men equally: The transport system shall be designed to meet the transport requirements of both men and women. Women and men shall be given equal opportunities to influence introduction, design and administration, and their assessments shall be afforded the same importance. (Government Bill Citation2001/02:20)

A gender-equal transport system was implemented as one of six sub-goals under the overall transport policy objective ‘to ensure the economically efficient and sustainable provision of transport services for people and industry throughout the country’ (Government Bills Citation2001/02:20 and Citation2005/06:160)

In 2008, the goal structure was changed so that the previously existing six different transport policy sub-goals were replaced by two sub-objectives, one covering accessibility and the other covering safety, environment and health. The specific goal of a gender-equal transport system disappeared, but its meaning is embedded in the sub-objective regarding accessibility, with a formulation stating that ‘the transport system will be gender equal, meeting the transport needs of both women and men equally’, followed by a specification that ‘the work methods, the implementation and the results of the transport policy are meant to contribute to a gender-equal society’ (Government Bill Citation2008/09:93). This specification eliminates a possible interpretation that the transport system should facilitate unequal travel patterns. Instead of delimiting gender equality to the transport sector, it has a bearing on gender equality in the whole of society. The main objective of Swedish gender equality policy is that women and men should have the same power to shape society and their own lives. This main objective is complemented by goals for gender equality regarding active citizenship, financial independence through paid work, education, unpaid home and care work, health and an end to men’s violence against women. Hence, the specification quoted above can be seen as an attempt to enforce gender mainstreaming. Following a close reading of documents we now show how this has been included in the governance of STA and how the transport agencies have responded.

Accounting for gender mainstreaming

The government’s instruction for STA (SFS Citation2010:185) does not explicitly mention gender mainstreaming. However, it is clear that STA must take measures to achieve the transport policy objectives and assist the new Transport Analysis (TA) agency in its annual reports of the achievements and status of the transport policy objectives. The Ministry of Enterprise and Innovation’s first appropriation directive for STA for Citation2010 includes a formulation relating to gender equality policy. Under the heading ‘Organizational governance’, it is stated that STA shall strive for an equal gender distribution in its organization. This commission can be interpreted to point more towards the government’s expectation of bringing in more women into a male-dominated sector than to gender mainstreaming of the results delivered by the agency’s core business. During the period 2011–2017, there were no indications of gender equality in the annual appropriation directives, with one exception. Prior to 2014, the directive stated that the specification of a gender-equal society in the transport policy sub-objective for accessibility must be reported back by STA and that all individual-based statistics must be broken down by gender. Any differences between women and men were also to be analysed and commented on. The government also requires that in cases where no gender-disaggregated statistics can be presented, the reason for this is to be reported.

STA’s annual reports contain some passages on gender equality, including a very brief description in connection to the overarching transport policy objectives, and also in connection with the reporting of internal personnel recruitment and competence development. The passages on gender equality that relate to the transport policy sub-objective for accessibility are primarily about explaining that STA views gender mainstreaming as a strategy for its operations, both regarding the agency’s deliveries to the transport system and from an employer perspective in relation to their employees: ‘Gender equality that contributes to the fulfilment of the transport policy goals co-operates with developed gender equality from an employer perspective. Taking advantage of women’s and men’s capacity and competence is an important prerequisite for the work on a gender-equal transport system’ (STA’s Annual Report, Citation2011).

From STA’s first two years of operation there are narratives under the headings: ‘A gender-equal society’ and ‘A gender-equal transport system’ (STA annual reports for, Citation2010 and Citation2011). STA says that they try to test different methods to improve the planning processes and, together with TA, develop goals, indicators and measures for the assessment of gender mainstreaming. However, this work is stalled due to a significant shift in STA’s accounting for its operations. ‘Delivery qualities’ were added to the governance to which the accounts for Citation2012 are adapted. The sub-objective of accessibility, in which gender mainstreaming is included, is now specified by the four delivery qualities punctuality, capacity, robustness and usability. There are no accounts for gender mainstreaming in Citation2012 and Citation2013. It is only the goal formulation itself that remains: ‘The transport system shall be designed to meet the transport requirements of both men and women’ (STA Annual Report, Citation2012, p. 14 and Citation2013, p. 14; authors’ translation). But there is no sign of any results.

In 2014, a section on gender equality in the transport system was introduced in the reporting of usability, which is defined as ‘the transport system’s ability to handle customer groups’ needs for transport opportunities’ (STA Report, Citation2012/11921, p. 10; authors’ translation). The customer groups that have been considered in the reporting of usability are mainly people with functional disability and industry in general, but without any gender perspective. There is only a brief description of the difference between women’s and men’s travel habits, along with a sentence stating that there is a link between gender equality and improved accessibility in the transport system.

In STA’s annual report for Citation2016, gender equality is linked to social sustainability and STA indicates that work is underway to ensure that the opinions of different groups are taken into account in infrastructure planning. The ambition is to invite underrepresented groups—younger and middle-aged men along with women of all ages—to the legally compulsory consultations in the planning process of infrastructure investments.

STA has the government’s commission to assist TA in an annual follow-up of the transport policy objectives. A development up to an equal distribution of women and men in boards and management groups for transport agencies and state-owned companies in the transport sector appears in the TA reports. TA states that they don’t have any indicators regarding the ability to make contact with citizens to be able to obtain a more equal representation of women and men at the consultation meetings in the planning process for infrastructure.

The differences in women’s and men’s use of the transport system, and what it means for the decision-making process, is mentioned in one report:

Since there are differences between men’s and women’s travel patterns, it is important to capture both men’s and women’s experiences in the decision-making processes that govern the development of the transport system. Among other things, it is important to have an equal representation of men and women in the decision-making assemblies of the transport system. (Transport Analysis Report, Citation2017b, pp. 29–30; authors’ translation.)

The government commissioned TA to review the specifications of the transport policy objectives and to make proposals for suitable indicators making them accountable (Ministry of Enterprise and Innovation, Citation2016). In terms of gender equality, eight different measures are specified for women and men within the indicator ‘Usability for everyone in the transport system’ (Transport Analysis Report, Citation2017a, appendix 2, para. 11). Some measures are set, for instance women’s and men’s travel patterns, gender distribution of ownership of vehicles and driving licences including mileage, female and male attitudes to road safety and security, and the differences between women’s and men’s sedentary lifestyles. When it comes to the distribution of power in the transport sector, TA states that the indicators for ‘Influence in the decision processes’ are not ready (ibid.). The proposal states that it should be measured with gender representation in management groups, boards, committees and the like per government agency, state-owned companies and municipalities. It is not clear how the further development of the indicators should take place (ibid.). The concept of power is commented on in a discussion on gender equality and security for all, in which TA refers to gender research:

There are many aspects in the presented gender research that need to be better captured and measured. However, parts of the reasoning seem somewhat abstract while at times it is done with rough brushstrokes … The different experiences of women and men are something we should bear in mind when interpreting the unclear formulation of the functional goal that the transport system should respond equally to women’s and men’s transport needs. This means that we should follow up and evaluate how actors in the transport sector ensure that both women’s and men’s experiences are taken into consideration when designing, planning and managing the transport system. (Transport Analysis, Citation2017a, pp. 41–42; authors’ translation.)

It takes time

There is still no analysis of gendered power relationships. And there is no follow-up on the question of how women’s reflected experiences are equated with those of men in the planning processes. A recurring issue in the literature on gender mainstreaming is why it is going so slowly. It has been almost two decades since the goal of a gender-equal transport system began to form part of the governance of the transport agencies. The goal formulations are repeated, sometimes only as a report without contents. TA writes that: ‘the follow up of gender equality should be developed. However, this will take time’ (Transport Analysis, Citation2017a, p. 42; authors’ translation).

It is clear that there are no indicators for how contacts are created with citizens in order to obtain a more equal representation of women and men at consultation meetings in the planning process for infrastructure. Such meetings give opportunities for the public to express their views, needs and interests. It is problematic that there is a significant overrepresentation of older men coming to the consultations, especially considering the first sub-goal of the gender equality policy objective, that women and men should have the same right and opportunity to be active citizens and to shape the conditions for decision-making. At this end, Levin et al. (Citation2016) point out that open consultation with the public risks giving insufficient information. In order to be able to make a gender equality impact assessment with relevant data, the open consultations need to be supplemented with data from a strategic selection of people. The authors, supported by Halling et al. (Citation2016), also argue that such well-structured data collection should be done before the public receives a proposal for transport planning in which gender aspects are already integrated. The fact that knowledge about gender equality needs to be integrated from the early planning stages has been discussed for many years, but it has not yet had impact:

The authors found that gender equality, along with other social aspects, is often ignored when planning comes to critical stages. Therefore, it is important to ensure that gender equality has a mandate to be a planning prerequisite that complements, for example, the environment and the economy. The responsibility for this should not be imposed on the group that works with the gender equality impact assessment, but on the person who manages the planning: the task leader and the sub-project leader must actively work to let the gender equality impact assessment take place. (Halling et al., Citation2016, p. 21; authors’ translation.)

The gender-equal transport system goal is considered unclear and gender studies analyses are seen as abstract (Transport Analysis, Citation2017a, pp. 40–43). But from a gender science perspective, the goal is crystal clear. It is about the power to influence the transport system’s introduction, design and administration, enabling contributions to a gender-equal society. Gender research has shown that such power relationships are multifaceted and need to be qualitatively assessed; a one-sided quantitative model is not adequate.

It requires will and knowledge

TA writes quite a lot about the need for equal representation of women and men in decision-making assemblies. But they also comment that this is only one factor among several. From a gender-scientific perspective, this is both a welcome and important insight as the notion of ‘representation’ is problematic when it comes to gender. TA’s reasoning can be interpreted as meaning that they have realized that women and men cannot be expected to represent their gender when it comes to decision-making. There is no evidence that the woman who is elected to a decision-making assembly for transport issues is knowledgeable on women’s wants and needs for transportation. On the contrary, it can just as well be that she is prepared to assimilate into the present agenda and prevailing culture.

Both women and men in decision-making positions can be aware of the experiences and interests of women and men in general. But to ensure that gender equality aspects are taken into account, they need to be included in the decision-making process (Halling et al., Citation2016). The gender balance that is reported for the transport sector's national agencies and public companies since 2013 may have an impact on gender mainstreaming. However, many decisions are made at regional and local levels and there, the ‘quota of women is worryingly low’ (Transport Analysis Report, Citation2017b, p. 32; authors’ translation).

In order for the transport system to contribute to a gender-equal society, the actors in the transport sector need to be familiar with the gender equality policy goals, take them into account and design the transport system for synergy effects between technical quality standards and gender equality. The risk is that the measurability trap will be opened when STA reports improved figures on the internal gender distribution. Gender mainstreaming is nothing that happens automatically through quantitative gender balance. The government’s writings on ‘real power’ show that there is an understanding of the difference between quantity and quality. Hence, state governance must mirror a genuine desire to follow up the qualitative aspects of gendered power relationships, and knowledge is required to enable a gender-aware analysis for management control purposes.

The extent to which an equal gender distribution in the transport sector contributes to achieving all the sub-goals of gender equality remains to be seen. It can be a prerequisite for asking critical questions about the lack of information from the public’s perspective for both women and men. But the question of power is central and needs to be highlighted with knowledge of how gender relations work. Such knowledge also includes transgender perspectives, so that it is not just people who identify as women or men who can participate in the discussion of what constitutes an accessible transport system.

Governance problems

The goal structure is important for governance and management control. Initially, a gender-equal transport system was formulated as a specific sub-goal, which resulted in visibility. The current goal structure has gender equality embedded in one of two transport policy sub-goals. What this means for gender mainstreaming needs further research.

TA’s proposal to monitor results based on the overall transport policy objectives rather than the more operationalized delivery qualities may result in an analysis that more accurately reflects a public value perspective. The STA vision probably also plays a role in focusing on public value, since it can be interpreted as a desire to maintain control in terms of an outside perspective—the citizens’ and industry’s experiences of smooth, green, safe transport. STA’s mission statement of necessary co-operation with other actors for societal development can also be interpreted as a way of organizing the operations within the concept of PVM.

The suggestion of having an expert panel that will assess a number of indicators together with qualities of the transport system is interesting. Indicators and expert panels fit well with a gender-scientific analysis model that covers both quantity and quality. However, the question is how this panel of experts should be appointed and work.

TA raises the problem and points out that the outcome of the weighting of the indicators may ‘depend more on who is part of the panel than on the mass of knowledge’ (Transport Analysis Report, Citation2017a, p. 38). How indicators are constructed, which data is captured and how the results are interpreted are influenced by who is doing the work. Prejudices impact the method of measuring, and even tacit knowledge is relevant to what is chosen to be measured (Power, Citation2004), which challenges a technocratic-oriented objectivity. Such technocratic or weak objectivity assumes that facts are non-valuable, impartial universal knowledge, while strong objectivity means that the relationship between the person measuring and what is measured needs clarification (Harding, Citation1991). The problem formulation have impact on the problem solution (Bacchi, Citation2008). In the transport sector, one question needs to be constantly recurring: is gender equality included in the formulation of the problem? The composition of individuals in the expert panels with varied and relevant competencies is crucial.

Can the measurability trap be avoided with PVM?

The problem with NPM and MBO in relation to gender mainstreaming can be discussed by asking how one can construct governance that gives ‘feminist-convinced bureaucrats’ (Alnebratt & Rönnblom, Citation2016, p. 158) the means to make a difference; how political logic can recover power over economic thinking. However, we propose that there are many important values in economy and efficiency for which we can thank NPM, not least based on the Swedish Budget Act’s regulations on both high efficiency and good economy in the state. Policy objectives should be achieved efficiently, but always in combination with equity and democracy. When an agency such as STA chooses to define its operations as societal development, and the government is in the process of shaping a form of governance beyond quantitative measurability, we interpret this as a promotion of governance with public value in focus. Public value is not unambiguous, which is positive when it comes to avoiding the dilemma of the measurability trap. Goal conflicts between efficiency and effectiveness—output and outcome—can be constructive if they are discussed from several perspectives. Managing public value is about equal and democratic processes, about how the work is done to achieve the political objectives. This is where we see that PVM, with its dialogic approach to diverging arguments, can work better for gender mainstreaming—but still on condition that a gender-aware analysis will take place. Regardless of the governance system in play, the success of gender mainstreaming requires both knowledge of gendered power relations and gender-aware actions to deal with inequalities. And you cannot ‘throw in the yeast after the dough’—gender mainstreaming does not come by itself. A progressive approach is to include gender-aware actions for gender equality as a prerequisite in all planning processes.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

References

- Aberbach, J., & Christensen, T. (2005). Citizens as consumers: An NPM dilemma. Public Management Review, 7(2), 225–246. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1080/14719030500091319

- Acker, J. (1992). Gendering organizational theory. In A. J. Mills, & P. Tancred (Eds.), Gendering Organizational Analysis. Sage.

- Acker, J. (2009). From glass ceiling to inequality regimes. Sociologie du travail, 51(2), 1991–217. DOI:https://doi.org/10.4000/sdt.16407

- Alnebratt, K., & Rönnblom, M. (2016). Feminism som byråkrati. Leopard förlag.

- Alvesson, M., & Sköldberg, K. (2018). reflexive methodology—new vistas for qualitative research. Sage.

- Andersson, R. (2018). Gender mainstreaming as feminist politics: a critical analysis of the pursuit of gender equality in Swedish local government. Dissertation, Örebro University.

- Bacchi, C. (2008/1999). Women, policy and politics: the construction of policy problems. Sage.

- Benington, J., & Moore, M.2011). Public value theory & practice. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Bovaird, T., Gregory, D., & Martin, S. (1988). Performance measurement in urban economic development. Public Money & Management, 8(4), 17–22. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1080/09540968809387502

- Brown, J. (2009). Democracy, sustainability and dialogic accounting technologies: taking pluralism seriously. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 20(3), 313–342. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpa.2008.08.002

- Callerstig, A.-C. (2011). Utbildning för en jämställd verksamhet. In K. Lindholm (Ed.), Jämställdhet i verksamhetsutveckling. Studentlitteratur.

- Connell, R. W. (2002). Gender. Polity Press.

- Cooper, C. (1992). The non and nom of accounting for (m)other nature. Accounting Auditing & Accountability Journal, 5(3), 16–39. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1108/09513579210017361

- Funck, E. K., & Karlsson, T. S. (2019). Twenty-five years of studying new public management in public administration: Accomplishments and limitations. Financial Accountability & Management, 36(4), 347–375. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1111/faam.12214

- Government Bill 2001/02:20 Infrastruktur för ett långsiktigt hållbart transportsystem. Ministry of Enterprise and Innovation.

- Government Bill 2005/06:160 Moderna transporter. Ministry of Enterprise and Innovation.

- Government Bill 2008/09:93 Mål för framtidens resor och transporter. Ministry of Enterprise and Innovation.

- Greve, C. (2015). Ideas in public management reform for the 2010s: digitalization, value creation and involvement. Public Organization, 15, 49–65. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11115-013-0253-8

- Halling, J., Faith-Ell, C., & Levin, L. (2016). Transportplanering i förändring: en handbok om jämställdhetskonsekvensbedömning i transportplaneringen. Nationellt kunskapscentrum för kollektivtrafik, K2.

- Harding, S. (1991). Whose science? Whose knowledge? Thinking from women’s lives. Cornell University Press.

- Häyrén, A. (2016). Constructions of masculinity: Constructions of context—Relational processes in everyday work. In A. Häyrén, & H. H. Wahlström (Eds.), Critical Perspectives on Masculinities and Relationalities (pp. 53–66). Springer. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-29012-6_5.

- Hines, R. (1992). Accounting: filling the negative space. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 17(3/4), 313–341. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/0361-3682(92)90027-P

- Holmblad Brunsson, K. (2005). Ekonomistyrning—om mått, makt och människor. Studentlitteratur.

- Hood, C. (1995). The ‘New Public Management’ in the 1980s: variations on a theme. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 20(2/3), 93–109. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/0361-3682(93)E0001-W

- ITF. (2019). Transport connectivity: a gender perspective. OECD Publishing.

- Jacquot, S. (2010). The paradox of gender mainstreaming: unanticipated effects of new modes of governance in the gender equality domain. West European Politics, 33(1), 118–135. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1080/01402380903354163

- Kanter, R. M. (1977). Men and women of the corporation. Basic Books.

- Levin, L., Faith-Ell, C., Scholten, C., & Aretun, Å. (2016). Att integrera jämställdhet i länstransportplanering—slutredovisning av forskningsprojektet implementering av metod för jämställdhetskonsekvensbedömning (JKB) i svensk transportinfrastrukturplanering. K2 Research. Nationellt kunskapscentrum för kollektivtrafik, K2.

- Lindholm, K.2012). Jämställdhet i verksamhetsutveckling. Studentlitteratur.

- Linghag, S., Ericson, M., Amundsdotter, E., & Jansson, U. (2016). I och med motstånd: förändringsaktörers handlingsutrymme och strategier i jämställdhets- och mångfaldsarbete. Tidskrift för genusvetenskap, 37(3), 9–28.

- Ministry of Enterprise and Innovation. (2016). Uppdrag att se över transportpolitiska preciceringar och lämna förslag till indikatorer för att följa upp de transportpolitiska målen. N2016/05490/TS.

- Modell, S., & Grönlund, A.2006). Effektivitet och styrning i statliga myndigheter. Studentlitteratur.

- Modell, S., & Wiesel, F. (2009). Consumerism and control: evidence from Swedish central government agencies. Public Money & Management, 29(2), 101–108. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1080/09540960902767980

- Moore, M. H. (1995). Creating public value: strategic management in government. Harvard University Press.

- Moore, M. H. (2013). Recognizing public value. Harvard University Press.

- Pincus, I. (2002). The politics of gender equality policy: a study of implementation and non-implementation in three Swedish municipalities. Dissertation, Örebro University.

- Power, M. (2004). Counting, control and calculation: reflections on measuring and management. Human Relations, 57(6), 765–783. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726704044955

- Prebble, M. (2012). Public value and the ideal state: rescuing public value from ambiguity. Australian Journal of Public Administration, 71(4), 392–402. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8500.2012.00787.x

- Rönnblom, M. (2002). Ett eget rum? Kvinnors organizering möter etablerad politik. Dissertation, Umeå University.

- Rönnblom, M. (2011). Vad är problemet? Konstruktioner av jämställdhet i svensk politik. Tidskrift för genusvetenskap, 2–3, 35–55.

- Rutgers, M. (2015). As good as it gets? On the meaning of public value in the study of policy and management. American Review of Public Administration, 45(1), 29–45. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/0275074014525833

- SFS 2010:185. Instruktion för Trafikverket. Ministry of Enterprise and Innovation.

- Sharp, R., & Broomhill, R. (2002). Budgeting for equality: the Australian experience. Feminist Economics, 8(1), 25–47. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1080/1354500110110029

- SOU. (2001). Jämställdhet—transporter och IT. Slutbetänkande från Jämit—Jämställdhetsrådet för transporter och IT.

- Squires, J. (2005). Is mainstreaming transformative? Theorizing mainstreaming in the context of diversity and deliberation. Social Politics: International Studies in Gender, State & Society, 12(3), 366–388. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1093/sp/jxi020

- STA annual reports. (2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015 and 2016). https://trafikverket.ineko.se/se/årsredovisning-2.

- STA report 2012/11921. Slutredovisning Regeringsuppdrag—införande av ett gemensamt styrramverk för drift och underhåll av väg och järnväg.

- Stoker, G. (2006). Public value management: a new narrative for networked governance? American Review of Public Administration, 36(1), 41–57. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1177/0275074005282583

- Swedish government website, Regeringen.se. . Visited May 2, 2021: https://www.regeringen.se/regeringens-politik/jamstalldhet/jamstalldhetsintegrering/.

- Thomson, K. (2017). Styrning och samhällsvärde: en studie med exempel från museivärlden. Dissertation, Stockholm University.

- Transport Analysis. (2017a). PM 2017:1. Preciseringsöversyn—indikatorer och uppföljning.

- Transport Analysis. (2017b). PM 2017:3. Preciseringsöversyn—målstyrning i teori och praktik.

- Transport Analysis Report. (2017a). 2017:1. Ny målstyrning i transportpolitiken.

- Transport Analysis Report. (2017b). 2017:7. Uppföljning av de transportpolitiska målen 2017.

- Wahl, A. (2003). Könsstrukturer i organizationer. Studentlitteratur.

- Wahl, A., Holgersson, C., Höök, P., & Linghag, S. (2018). Det ordnar sig. Studentlitteratur.

- Wittbom, E. (2011). I själva verket: könsblind styrning. In L. Freidenvall, & J. Rönnbäck (Eds.), Bortom rösträtten: kön, politik och medborgarskap i Norden (pp. 215–232). Södertörn University.

- Wittbom, E. (2015). Management control for gender mainstreaming—a quest of transformative norm breaking. Journal of Accounting & Organizational Change, 11(4), 527–545. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1108/JAOC-08-2012-0069