?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.IMPACT

This article looks at how the roles and personal characteristics of politicians affect their use of accounting information. The findings in this article suggest that it is very likely that the quality of debates in parliament correlate with use of the accounting information provided. Political parties should consider age and experience in their selection of candidates and in terms of whether to retire MPs, because age and experience do seem to affect the extent to which politicians substantiate their statements and decisions with hard accounting information.

ABSTRACT

Recent literature calls for more research on the context and drivers of information use, and how this affects the information-seeking behaviour of politicians. This article addresses this gap by exploring antecedents of politicians’ accounting and other types of information use. It looks at parliamentary debates in the Dutch central government linked to the budget cycle—how accounting information is balanced with other sources of information. Political roles (for example being member of a coalition or opposition party, or being a party’s financial spokesperson), as well as personal characteristics (age and experience), were found to have an impact on the extent of accounting and other types of information use.

Introduction

In recent years, the use of sources of accounting information by politicians has received attention from a range of researchers. In the public sector financial management literature (for example van Helden, Citation2016; van Helden & Reichard, Citation2019), the focus has been on the interplay between user needs, usability and the actual use of accounting information. The expectation is that if user needs are fulfilled, this leads to usability and, when usability is in place, this leads to use. However, the antecedents influencing usability and actual use of accounting information have received much less attention (exceptions include Buylen & Christiaens, Citation2016; and Sinervo & Haapala, Citation2019; van Helden & Reichard, Citation2019). More research is needed on the context and drivers of information use, and how this affects the information-seeking behaviour of politicians and public managers (van Helden, Citation2016).

The purpose of this article is to address this gap by exploring possible drivers of politicians’ information use. An observational study was conducted in the empirical domain of parliamentary debates in Dutch central government linked to the budget cycle. We investigated which actors referred to specific sources of information in political debates, and to what extent they referenced accounting information and other sources of information. Following Liguori et al. (Citation2012) and Jorge et al. (Citation2019), we included both budgetary and financial reporting in our definition of accounting information.

In analysing the drivers of politicians’ information use, we distinguished between differences in political roles and differences in the personal background characteristics of politicians. We used insights from the upper echelons theory (Hambrick & Mason, Citation1984; Anessi-Pessina & Sicilia, Citation2020), which suggests that managers’ personal characteristics affect the way they act and make decisions. The extent to which accounting information and other sources of information was used varied among politicians depending on their political roles and personal background characteristics.

Literature on the drivers of information use

Accounting information can assist in evaluating performance, as well as in monitoring and controlling activities. The role of accounting information in government grew tremendously through the New Public Management (NPM) paradigm, when various administrative reforms based on private sector practices were put in place to supplant the hierarchical, bureaucratic tradition of public organizations with a way of working on a contract basis (Broadbent et al., Citation1996; Pollitt & Bouckaert, Citation2011). Hood (Citation1995) saw ‘accountingization’ and results-oriented accountability as major elements of NPM, and they still resonate in most of today’s public accountability structures. This rational–economic perspective on information use in the public sector is increasingly subject to criticism. In their recent literature review, van Helden and Reichard (Citation2019, p. 491) observe a ‘slow but steady shift’ in the overall reporting perspective, from an accountant’s viewpoint toward a ‘professional and needs-driven perception of financial information’.

In the realm of politics, the elements of NPM are also being challenged. One prominent research finding is that politicians consider accounting information as potentially important, but the actual use lags behind this potential, and politicians seem to prefer non-financial and informal verbal information above accounting information (Liguori et al., Citation2012; Sinervo & Haapala, Citation2019). Some antecedents for the actual use of accounting information that have been described in the literature are the role of politicians in legislation (as a member of the governing or an opposition party), political ideology, political competition, political experience, and financial expertise (Buylen & Christiaens, Citation2016; Giacomini et al., Citation2016; Hyndman et al., Citation2008; Sinervo & Haapala, Citation2019). Additionally, in political science the difference in behaviour between members of established and new political parties has also been an area of research (see for example Otjes, Citation2012). However, in the domain of accounting information use by politicians, several overview articles (van Helden, Citation2016; van Helden & Reichard, Citation2019) noticed the abundance of survey- and interview-based studies. This underlines the need for other research methods, such as observational studies.

This article is an observational study of drivers of information use in the Dutch parliament, focusing on the political roles and personal background characteristics of potential information users. Although our study relied on minutes, which suggests content analysis as a primary method, the study could be considered observational: the minutes that were used form a comprehensive account of the underlying political debates and are a good proxy for live observation. One possible drawback of this method is that the researchers could not register the speakers’ body language and different pitches and speech rates during live debates.

Political roles

As Buylen and Christiaens (Citation2016) indicate, political conditions influence the use and application of information. These conditions can relate to the political climate in a specific setting (for example political competition and fragmentation) and the roles politicians have. As we focus on one empirical setting (the Dutch parliament), differences in political climate are not relevant in our study. However, differences in political roles seem to be highly relevant.

First of all, several studies have shown that politicians’ use of accounting and other information depends upon their roles (for example Askim, Citation2009; Lu & Willoughby, Citation2018). Those who are active in the executive branch are expected to use information more extensively, as they are responsible for day-to-day operations, whereas those in the legislative branch have a less active role. In our empirical setting, members of government (MGs) are part of the executive branch, whereas members of parliament (MPs) are in the legislative branch. Recently, there has been some discussion in the Netherlands regarding the information asymmetry within central government. The capacities of Dutch politicians for seeking and processing information is considered disproportionate to the numbers of staff available to MGs. Several motions were accepted in 2019 by parliament which called for more support staff (Motion Özturk, Citation2019; Motion Jetten, Citation2019). We therefore expected that MGs would be better versed in information seeking and would make more use of information than MPs. This led to our first proposition:

P1: MGs are likely to use more accounting information and other sources of information compared to MPs.

Whereas our first proposition focuses on the differences between MGs and MPs, our remaining propositions apply solely to MPs, as the characteristics under study are best applicable to this group. Several previous studies point to differences between MPs who represent a political party in a government coalition and those who do so for an opposition party. However, Sinervo and Haapala (Citation2019) indicate that prior literature on this issue shows mixed results. Askim (Citation2009) states that politicians who belong to coalition parties are expected to have better access to information than their counterparts from the opposition. However, Buylen and Christiaens (Citation2014) indicate that, as a result of party discipline, politicians of a governing party might be less eager to be critical. As we did not know which effect would apply in the Dutch context, our second proposition was in the null form:

P2: MPs who represent a party in a government coalition use accounting information and other sources of information to the same extent as their counterparts in the opposition.

Another element that may have an influence on the use of accounting and other sources of information is the political party a politician represents. Previous research on this issue has focused on the ideology of the political party. However, as Sinervo and Haapala (Citation2019, p. 563) indicate, ‘how ideology affects this use is a controversial topic’. This also has to do with the way ideology is generally measured, i.e. by making a distinction between left-wing and right-wing parties. In the Netherlands, currently 17 political parties are represented in the national parliament and these differ in a number of ways, which cannot be easily summarized on the left–right dimension. However, literature in the area of public administration has pointed to differences between traditional and non-traditional parties in the Dutch context. Otjes (Citation2012) argued that institutionalized, structured decision-making in parliament can marginalize non-traditional political parties. However, it is also possible that new parties may exploit this mechanism and have a major influence on decision-making: suggesting lower use of information by newer parties. Simultaneously, the emergence of new political parties can be an external shock that disrupts institutionalized parliamentary decision-making, allowing them to put new topics on the parliamentary agenda. We did not expect to find differences for the extent of information use:

P3: MPs who represent a newer political party are expected to use accounting information and other sources of information to the same extent as their counterparts from established parties.

The fourth difference in political roles that may have an influence is the role in parliament. Hyndman et al. (Citation2008) suggested that financial ‘insiders’ in parliament, such as members of the budget committee, have a reasonably good understanding of financial figures. Politicians that act as the financial spokesperson of their party might be better suited to debate in the context of the budget cycle of Dutch central government, as they are more likely to process and use information that is linked to the planning and control cycle:

P4: MPs who are in a financial role in their political party are likely to use more accounting information but the same sources of information compared to their counterparts who do not have this role.

Personal background characteristics

Previous literature on the use of accounting and other information by politicians has already shown that the individual background characteristics of politicians may play a role in explaining the extent of accounting information and other sources of information (see especially Sinervo & Haapala, Citation2019 about accounting information, and Askim, Citation2009 for performance information). Especially, educational background and experience have been discussed. An exploratory analysis revealed that the role of financial spokesperson is often filled in by a politician with an educational background in economics and business administration, making it difficult to isolate the effects of political role and education.

As far as experience is concerned, previous literature has shown mixed results. Askim (Citation2009) hypothesized that politicians’ use of performance information increases with the length of their political experience, but found conflicting results. However, Sinervo and Haapala (Citation2019) formulated the same hypothesis for the use of accounting information and did find support for this. These contradictory findings have been corroborated by differences in theoretical expectations. First, it might be expected that the more experienced a politician is, the more they are able to develop the abilities and skills to collect and interpret information (for example Askim, Citation2009). Second, and on the contrary, more experienced politicians may be less inclined to collect information when they have to make a decision (Askim, Citation2009) and ‘less experienced politicians are expected to be open-minded to new information, while political veterans rely on routine’ (Sinervo & Haapala, Citation2019, p. 564).

As previous literature on the influence of personal characteristics produced ambiguous results, we employed insights from the upper echelons theory (UET) to delve deeper into this issue. The theory builds on Cyert and March (Citation1963) and March and Simon (Citation1958), who observed that when it comes to information-seeking behaviour, people tend to draw upon their past experiences. These experiences serve to filter the decision-makers’ perceptions of current events, and how they act on them. Following from the bounded rationality perspective, Hambrick and Mason (Citation1984) describe two core premises from UET: executives act on the basis of their personalized interpretations of the strategic situations they face; and these interpretations are a function of the executives’ experiences, values, and personalities. As the psychological dimensions that may influence the behaviour and decisions of managers are hard to observe, Hambrick and Mason (Citation1984) suggest using observable managerial characteristics, such as age, tenure in the organization, functional background, and education, and define these as the drivers for strategic choices. These choices, in their interaction with managers’ background characteristics, are at the heart of what drives performance.

UET has been applied extensively in research on the private sector. Specifically, several studies also analysed the influence of top managers on disclosure practices (for example Bamber et al., Citation2010; Ge et al., Citation2011). One overview study, on the application of UET in management accounting and control research (Hiebl, Citation2014), suggests that younger chief financial officers (CFOs) and senior managers with shorter appointments preferred more advanced management control systems. This was also found for managers with a background in business administration. In spite of its popularity in the private sector studies, the UET perspective is less often applied in the context of the public sector. Moreover, when it is applied, it is mostly focused on public sector managers (see for example Kearney et al., Citation2000; Suzuki & Avellaneda, Citation2018), rather than politicians. However, a recent paper by Anessi-Pessina and Sicilia (Citation2020) demonstrated that UET can successfully be applied to investigating accounting practices in the public sector. By using data derived from databases, as well as a survey sent to the CFOs of all Italian municipalities with more than 15,000 inhabitants, they showed that top managers’ individual characteristics influence the extent of accounting manipulation.

For this article, we argue that UET provides a fruitful perspective to explore drivers for accounting information use in the political arena. However, there are two important differences from the original UET framework. First, UET is primarily about the influence of personal characteristics of stakeholders on strategic choices, whereas we look at the effect on information use. In this respect, it should be noted that the process of decision-making in parliament forms the link in a complex and layered process of information processing (Enthoven, Citation2011). However, we assume that information use ultimately has an impact on the quality of the debate and therefore on its outcomes. Second, UET looks at background characteristics of (top) managers, whereas this study looks at politicians. This was because politicians are generally the key decision-makers in the public sector (Hyndman, Citation2016); particularly, as the parliament controls the central government and makes laws, the Dutch parliament can be seen as a locus of decision-making.

Following UET reasoning, we think that personal background characteristics of MPs may influence the extent of information use. Following Hiebl (Citation2014) and Anessi-Pessina and Sicilia (Citation2020), we distinguished four characteristics that may be relevant: experience; age; education; and differences between men and women. Beginning with the last-mentioned characteristic, several studies suggest that women are more risk averse, more ambiguity averse, and less likely to engage in unethical behaviour than men (Anessi-Pessina & Sicilia, Citation2020). As our study was about the use of information, and not about the search for information or decision-making, we felt that the differences between men and women were not relevant so we did not include them in our empirical analysis. Second, as a result of possible multicollinearity problems (as the position of financial spokesperson is frequently held by a politician with an educational background in economics and business administration), we were not able to analyse that issue. Therefore, we focused on age and experience.

Classic UET literature finds that younger executives appear to be much more associated with achievements and corporate growth (Child, Citation1974), or are more capable of developing and implementing new ideas (Hambrick & Mason, Citation1984; Anessi-Pessina & Sicilia, Citation2020). Recently, Alesina et al. (Citation2019) found evidence that younger politicians engage more in political budget cycles on public investment than older ones. They ascribe this to the fact that younger politicians have a longer time horizon in their career, and could therefore be more willing to engage in strategic policies to ensure re-election. As far as information use is concerned, we think that younger politicians will use information more than older politicians, and that they will use this information to substantiate their proposals:

P5: Younger MPs are likely to use more accounting and other sources of information compared to their older colleagues.

Hiebl (Citation2014) observed that several studies found that younger and shorter-tenured CFOs are associated with increased use or higher sophistication of management accounting and control systems. This corroborates the expectation in studies on politicians’ use of information that newly-elected politicians have a higher need for information (Sinervo & Haapala, Citation2019). Therefore, and contrary to the expectations of Askim (Citation2009) and Sinervo and Haapala (Citation2019), we think that novices use information more than their more experienced counterparts. We do not have indications that there are any differences between accounting information and other sources of information:

P6: Novices are likely to use more accounting and other sources of information compared to experienced MPs.

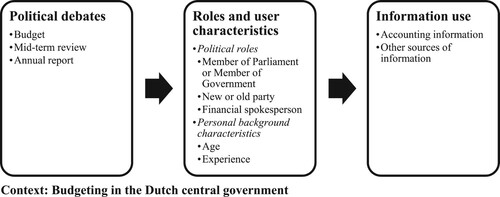

summarizes the framework that was developed for this article, adjusted for the empirical domain of parliamentary debates in Dutch central government linked to the budget cycle. It depicts the objective situation for our observational study: political debates addressing the various stages of the budget cycle. Debates on the budget were chosen as it is expected that actors within this setting are most inclined to use accounting information in order to conduct informed decision-making. Within this situation, we monitor the roles and characteristics of the politicians and scrutinize their influence on information use. In line with UET, our assumption was that information use ultimately has an impact on the quality of the debate and therefore on its outcomes.

Context: Budgeting in the Dutch central government

In the Netherlands, the parliament consists of two chambers (the House of Representatives and the Senate) and has two main tasks: controlling the government and law-making. The government is also obliged to inform parliament about the budget so that they can properly monitor the government. Each annual budgeting cycle in the Dutch central government takes approximately two-and-a-half years and consists of three phases (Budding & van Schaik, Citation2015; House of Representatives, Citation2021):

Budget preparation.

Budget execution.

Accountability.

Budget preparation starts in year t – 2 with state budgetary guidelines being sent by the minister of finance to ministerial colleagues. Over the summer of year t – 1, each ministry prepares its own budget and the ministry of finance drafts the budget memorandum. In mid August, the final drafts are sent to the council of ministers for a decision.

The official opening of the parliamentary year is the third Tuesday of September on Prince’s Day, when the monarch delivers the speech from the throne. This is where parliamentary debates on the budget cycle of year t formally start with the general political considerations, where party chairmen discuss the speech from the throne with the prime minister, together with the budget memorandum. This is an important debate, as it shows what room the government has to carry out its plans and how strong its support is for doing so. The debate usually lasts two days, with plenty of media attention. This process continues with the general financial considerations, where generally financial spokespersons debate with the minister of finance and the undersecretary about the proposal. Until the end of year t – 1, separate budget debates are organized for each ministry in parliamentary subcommittees with delegated party specialists on the subject.

Execution of the budget starts on 1 January of year t. If a minister wants to spend more than the budget allows, parliament must be asked for permission. Before that, the minister of finance has to be asked for their opinion. Ministers are subject to strict budget rules, which are set at the start of each coalition period. These rules include (among others) that a minister’s new policy should be covered within their own budget and that overruns should be compensated for within the ministry in which these take place. During year t, the budget is formally monitored twice with the spring and autumn memoranda, which provide an interim summary of windfalls and setbacks to the current budget. If a minister needs more money than according to the budget, a supplementary budget is needed. These must be debated and approved by parliament. The spring and autumn memoranda are followed by a debate between financial spokespersons and the minister of finance.

At year end, each ministry prepares its own annual report and the ministry of finance also produces the central government annual financial report, combining the financial statements of all ministries. Together with the audit reports conducted by the Dutch supreme audit institution, the Algemene Rekenkamer, the reports of each ministry are presented to parliament on the third Wednesday in May of year t + 1: the so-called ‘accountability day’. This is followed by a scheduled accountability debate with the minister of finance. The budgetary cycle formally ends with the approval of the ‘final laws’ by the parliament.

Method

Our main goal was to explore to what extent the political roles and personal user characteristics of politicians influence their information use. In line with Buylen and Christiaens (Citation2016), we conducted a textual analysis of contributions to debates made by politicians in order to assess the referencing of sources of information in these discussions. The Dutch parliament’s reporting and editing service (Dienst Verslag en Redactie) produces verbatim reports of the plenary sessions of the House of Representatives and the Senate. These debates are then placed online in a document via the web portal of Official Notices (officielebekendmakingen.nl). This website discloses parliamentary debates as ‘acts’ (Handelingen); these are the official edited verbatim minutes of the plenary sessions of the Dutch parliaments. We collected the parliamentary debates related to the budgetary cycle between 2013 and 2018. These debates covered the budget, mid-term reviews (spring and autumn memoranda), and the annual report. shows that a total of 397 documents was collected and analysed (a list of the documents used is available on request from the authors). This also shows the central role of budgeting in public sector decision-making (see for example IPSASB, Citation2006; van Helden & Reichard, Citation2019).

Table 1. Phase of the budget cycle to which collected documents (N = 397) are related.

After the documents were collected, the types of sources referenced by the speakers were documented. Inspired by Askim’s (Citation2007; Citation2009) distinction between performance information and other sources of information, we distinguished two types of sources that could be referenced by politicians: accounting information and other information. We defined accounting information as information stemming directly from the governmental budget cycle and subject to legal regulations on budgeting and accounting, i.e. the Dutch Budgeting and Accounting Act (Citation2016) and the Governmental Budgeting Regulation (Citation2021). As well as budgets and annual reports, the spring and autumn memoranda contain supplementary budgets which are subject to these provisions, so we included them as ‘accounting information’. All remaining sources of information were grouped into ‘other sources of information’. This category includes agendas; evaluations; policy reviews; guides and manuals; letters to parliament; monitors; memoranda other than the spring and autumn memoranda; reports; coalition agreements; reports by the supreme audit institution; reports by the assessment agencies; legal texts, proposals and amendments; websites, apps, and other new media; parliamentary inquiries; other research reports; and media or press. As the primary focus of this article is on differences between roles and user characteristics, we did not make comparisons between the degree of use of accounting information and the degree of use of other sources of information.

A list of search terms was compiled for these two types of sources, building on the sources found by Faber and Budding (Citation2019) and which was validated by an expert committee.

In line with Buylen and Christiaens (Citation2016), the presence of these types of information was assessed by analysing the actual referencing during the political debates. However, we departed from earlier conceptualizations that looked at referenced words in the debates. Based on concepts from structural linguistics (see for example House of Representatives, Citation1984), we assumed that paragraphs are a psychologically real unit of discourse. Conversely, the text corpus for each of the assessed actors was not represented as a bag-of-words but, rather, as a set of coherent units of discourse, i.e. paragraphs. If one of the keywords was used in a paragraph, then this paragraph was counted as a unit of discourse in which the information source was used. Given that the debates took place in the context of the budget cycle, it was likely that the substance of the debate would be grounded in the (accounting) information disclosed by the government and related to the phase the budget was in at the moment the debates took place. Therefore, the measure of use for the two types of information sources per actor was calculated using the following equation:

where was the number of paragraphs in which the information type is referenced, and

was the total number of paragraphs of the actor involved.

Pearson’s chi-squared tests were executed for all variables to determine whether there were statistically significant differences between the expected and observed proportions of information use. Additional Mann-Whitney tests were conducted in order to test for robustness, from which the results to a very large degree overlap with the results from the chi-squared tests presented here.

The documents with the minutes were split at paragraph level. Procedural remarks made by chairpersons, motions, and other formal comments were trimmed. Accordingly, a total of 103,285 paragraphs was collected. The following characteristics of the speakers were collected (see also ):

Political role: MP or MG (dichotomous, abbreviated as ROLE).

Party affiliations: coalition or opposition party member (dichotomous, AFF1); member of a party created before or after the year 2000 (dichotomous, AFF2).

Financial spokesperson (dichotomous, FIN).

Age (measured in years, AGE).

Experience during debate (number of days active in parliament, EXP).

Table 2. Descriptive statistics.

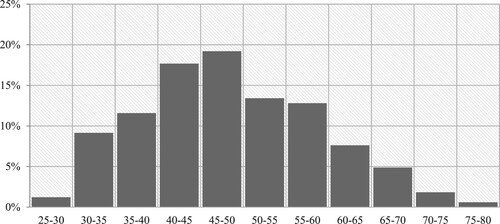

We identified 327 unique people in the debates; 21 of them had fulfilled multiple roles in the parliament over the years, for example as an MP as well as an MG. In addition, it should be noted that the distribution of statements by individuals was somewhat peaked: the top 25 people were responsible for approximately 25% of the statements (31,490 absolute observations). Next to this, 12% were MGs, compared to 88% MPs. The average experience of MPs was 2,105 days (about seven years), and the average age was 47.6 (see also ).

Results

As a first step in our analysis, we looked at differences in information use that could be explained by taking the role of the user into account (see ). Looking at the differences between MPs and MGs, we found that their use of accounting information was comparable, although the difference was statistically significant. Looking at the use of other sources of information, the difference in information use was even larger. This means that MGs used these sources much more in debates around the budget cycle than MPs did, supporting P1.

Table 3. Differences in information use between actors.

The remainder of this results section specifically concerns the MPs. MPs affiliated with coalition parties used accounting information as well as other sources of information to a higher extent, providing no support for the null hypothesis in P2. Likewise, we found significant differences between members of newer and established parties, suggesting a rejection of P3; the difference was notably larger for the use of accounting information. Finally, financial spokespersons made significantly more use of both information types than other MPs. This provides partial support for P4, where we argued that the use of accounting information would be higher, but that the use of other sources of information would be similar for MPs who were not financial spokespersons.

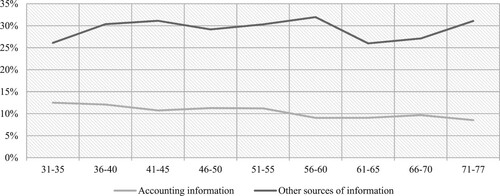

With respect to age, we found that younger MPs used accounting information and other sources of information slightly more than older MPs. This finding was only statistically significant for accounting information use, providing partial support for P5. In order to further explore this continuous variable, a glance at the use of information for age groups of five years (see ) provides more evidence for the trend that the older the person, the less they are inclined to use accounting information. However, this trend could not be observed for the other sources of information.

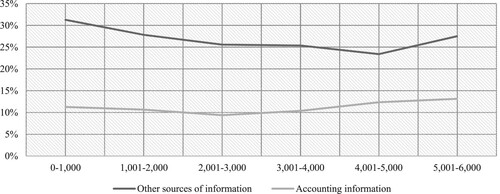

Politicians’ experience (i.e. the number of days a person had been active in the parliament at the time of the debate) provides findings comparable to those for age: more experienced MPs used accounting information and other sources of information much less than their less experienced colleagues. These differences were statistically significant, supporting P6. Looking more closely at the differences between levels of experience (see ), we observed that the longer someone was active in parliament, the less they were inclined to use other sources of information. For accounting information, this trend was not clear: we found indications of a U-curve in which the use of accounting information was lowest around 2,500 days (about seven years in parliament) and highest around 4,500 days (about 12 years in parliament). In addition, use was relatively high for recently appointed MPs. Note that this contradicts the findings with respect to the dichotomous variable EXP in : one explanation for this could be that the number of observations for the amount of days was not evenly distributed (this was already evident from the fact that the number of observations for parliamentarians with up to 1,878 days of experience accounted for half of the sample).

Conclusion, limitations, and future research

Using a large dataset of political debates that took place in the context of the budget cycle of the Dutch central government between 2013 and 2018, we analysed the use of accounting information and other sources of information during political debates. Our main goal was to explore to what extent the political roles and personal user characteristics of users were influencing their information use. Although almost all differences in the extent to which political roles and personal characteristics of users influenced their information use were statistically significant, the absolute differences seem small.

First, we found that MGs were likely to use more accounting information and other sources of information compared to MPs. Although several studies have shown that politicians’ use of accounting and other information depends upon their roles (for example Askim, Citation2009; Lu & Willoughby, Citation2018), our finding that MGs use more information is novel and could partly be attributed to the Dutch context, where MPs have far less assistance from supporting staff than MGs. Next to this, it was found that MPs who represent a party in a government coalition used more accounting information and other sources of information than opposition members.

Members of established parties used more of both types of information than non-traditional parties, particularly in terms of accounting information. This seems to support the argument of Otjes (Citation2012) that institutionalized, structured decision-making in parliament could marginalize non-traditional political parties, who may be less acquainted or equipped to keep track of the relevant information during important moments in the budgetary phase. Finally, parliamentarians acting as a financial spokesperson of their political party used more accounting information and other sources of information compared to their counterparts who do not have this role. This supports Hyndman et al.’s (Citation2008) suggestion that financial ‘insiders’ in parliament, such as members of the budget committee, have a reasonably good understanding of financial information. However, we discovered that this understanding stretches beyond the realm of the budget cycle, as a difference in favour of the financial spokespersons was also found for other sources of information.

With respect to personal background characteristics, younger MPs were likely to use more accounting and other sources of information compared to their older colleagues. This fits with the UET proposition that younger executives are more associated with achievement and corporate growth (Child, Citation1974) and that they are better at developing and implementing new ideas (Hambrick & Mason, Citation1984; Anessi-Pessina & Sicilia, Citation2020). As well, it fits with the idea that younger MPs could behave more strategically in response to electoral incentives, as they expect to have a longer political career and therefore stronger career concerns (Alesina et al., Citation2019). Support was also found for the proposition that novices are likely to use more accounting and other sources of information compared to more experienced MPs. This finding is different from the expectations as documented in other literature (Askim, Citation2009; Sinervo & Haapala, Citation2019); an explanation for this could be that newly-elected politicians have a higher need for information, and are more open-minded to it, while political veterans rely on routine (cf., Sinervo & Haapala, Citation2019).

Additionally, an approximation of a U-curve was observed in the use of accounting information and level of experience. One possible explanation for this could be that early career politicians are still unfamiliar with the different types of information, whereas mid-career politicians know what is available and how to use it (see Patzelt et al., Citation2008); this applies particularly to accounting information which can be very technical and requires more capabilities and skills than information from other sources. Finally, experienced politicians rely less on information and are better versed in the political game.

Future research

Our study suggests several avenues for future research. First, the point of departure for this article was the distinction between accounting information—defined as information stemming directly from the budgetary cycle—and other sources of information. This distinction does not consider information from the policy evaluation cycle. A vital direction for future research is making a distinction between accounting information, evaluation information and other information. This is interesting, because evaluation information is usually connected to broad issues of societal impacts and public service effectiveness, and may also be more useful to politicians who are less versed with more technical issues of accounting and budgeting, but interested in how political objectives and societal aims have been pursued and achieved (see also van Helden et al., Citation2012). Second, this article does not consider the symbolic and conceptual uses of information (Cyert & March, Citation1963; van Dooren & van de Walle, Citation2018; Weiss, Citation1979; Citation1980). The findings of this study should therefore be complemented by other types of studies in this area.

Another avenue for future research is factoring in electoral cycles—building on the argument of Alesina et al. (Citation2019) that politicians might behave more strategically in response to electoral incentives. As well, group heterogeneity was not considered as a driver for information-seeking behaviour (Hambrick & Mason, Citation1984) and this could be explored further. Finally, as the scope of this study was the referencing of sources of information by politicians, we did not look at the (qualitative dimension of) actual use of accounting information in the political arena. Some differences in use could be explained by the way in which the political debate takes place, for example MPs questioning MGs: these questions might be less substantiated by information, whereas answers need to be grounded by accounting and other sources of information. Moreover, the behaviour of individuals could be vital in pushing particular topics, subjects, or sources of information during sessions. More in-depth research is required to scrutinize the actual use of information and how this is relates to a politician’s role and personal characteristics.

Implications

This article has important practical implications. First, we observed that the extent to which statements were substantiated depended on which individuals engaged in these debates. Therefore, the quality of the debates around the budget cycle, and consequently the outcomes of the debates, was not only driven by the actions and behaviour of MGs and their civil servants, but also by those of MPs. Second, our findings show the importance of political parties considering age and experience in their choice of MP candidates, as both influence the extent to which politicians substantiate their statements with accounting information and other sources of information. This fact could impact the quality of debates and, therefore, their outcomes.

Acknowledgments

This research was made possible with financial support from the Netherlands Ministry of Finance and the Netherlands Court of Audit. We are grateful for helpful comments on earlier drafts provided by two anonymous reviewers, Jan van Helden, Henk ter Bogt, and Eelke Wiersma, as well as participants in the CIGAR Conference in Amsterdam (2019), the ARCA seminar in Amsterdam (2019) and the online ABRI seminar (2020).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

References

- Alesina, A., Cassidy, T., & Troiano, U. (2019). Old and young politicians. Economica, 86(344), 689–727. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/ecca.12287

- Anessi-Pessina, E., & Sicilia, M. (2020). Do top managers’ individual characteristics affect accounting manipulation in the public sector? Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 30(3), 465–484. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/muz038

- Askim, J. (2007). How do politicians use performance information? International Review of Administrative Sciences, 73(3), 453–472. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/0020852307081152

- Askim, J. (2009). The demand side of performance measurement: Explaining councillors’ utilization of performance information in policymaking. International Public Management Journal, 12(1), 24–47. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/10967490802649395

- Bamber, L. S., Jiang, J. X., & Wang, I. Y. (2010). What’s my style? The influence of top managers on voluntary corporate financial disclosure. Accounting Review, 85(4), 1131–1162. DOI: https://doi.org/10.2308/accr.2010.85.4.1131

- Broadbent, J., Dietrich, M., & Laughlin, R. (1996). The development of principal–agent, contracting and accountability relationships in the public sector: Conceptual and cultural problems. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 7(3), 259–284. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1006/cpac.1996.0033

- Budding, T., & van Schaik, F. (2015). Public sector accounting and auditing in the Netherlands. In I. Brusca, E. Caperchione, S. Cohen, & F. Manes Rossi (Eds.), Public sector accounting and auditing in Europe (pp. 142–155). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137461346_10

- Budgeting and Accounting Act. (2016). (Comptabiliteitswet 2016) (2017).

- Buylen, B., & Christiaens, J. (2014). Why are some Flemish municipal party group leaders more familiar with NPM practices than others? Assessing the influence of individual factors. Lex Localis—Journal of Local Self-Government, 12(1), 79–103.

- Buylen, B., & Christiaens, J. (2016). Talking Numbers? Analyzing the presence of financial information in councilors’ speech during the budget debate in Flemish municipal councils. Local Government Studies, 19(4), 453–475. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/10967494.2015.1064502

- Child, J. (1974). Managerial and organizational factors associated with company performance. Journal of Management Studies, 11(3), 175–189. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.1974.tb00693.x

- Cyert, R. M., & March, J. G. (1963). A behavioral theory of the firm. Prentice Hall.

- Enthoven, G. M. W. (2011). Hoe vertellen we het de Kamer? Een Empirisch Onderzoek naar de Informatierelatie tussen Regering en Parlement. Eburon.

- Faber, B., & Budding, G. (2019). Weinig consistent, beperkt zelfkritisch: De uitwerking van de beleidsconclusie binnen de rijksverantwoording. Bestuurskunde, 28(4), 76–88. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5553/bk/092733872019029004008

- Ge, W., Matsumoto, D., & Zhang, J. L. (2011). Do CFOs have style? An empirical investigation of the effect of individual CFOs on accounting practices. Contemporary Accounting Research, 28(4), 1141–1179. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1911-3846.2011.01097.x

- Giacomini, D., Sicilia, M., & Steccolini, I. (2016). Contextualizing politicians’ uses of accounting information: accounting as reassuring and ammunition machine. Public Money & Management, 36(7), 483–490. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/09540962.2016.1237128

- Governmental Budgeting Regulation (Rijksbegrotingsvoorschriften). (2021). Netherlands Ministry of Finance.

- Hambrick, D. C., & Mason, P. A. (1984). Upper echelons: The organization as a reflection of its top managers. Academy of Management Review, 9(2), 193–206. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1984.4277628

- Hiebl, M. R. (2014). Upper echelons theory in management accounting and control research. Journal of Management Control, 24(3), 223–240. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00187-013-0183-1

- Hood, C. (1995). The ‘new public management’ in the 1980s: variations on a theme. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 20(1), 93–109. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/0361-3682(93)E0001-W

- House of Representatives. (1984). Cues people use to paragraph text. Research in the Teaching of English, 18(2), 147–167.

- House of Representatives (Tweede Kamer). (2021). Hoe de Tweede Kamer de rijksuitgaven controleert. Infographic. https://www.tweedekamer.nl/sites/default/files/atoms/files/infographic_-_hoe_de_tweede_kamer_de_rijksuitgaven_controleert_2020.pdf.

- Hyndman, N., et al. (2008). Accounting and democratic accountability in Northern Ireland. In M. Ezzamel (Ed.), Accounting in politics. Devolution and democratic accountability. Routledge.

- Hyndman, N. (2016). Accrual accounting, politicians and the UK with the benefit of hindsight. Public Money & Management, 36(7), 477–479. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/09540962.2016.1237111

- IPSASB. (2006). Public sector conceptual framework.

- Jorge, S., Jorge de Jesus, M. A., & Nogueira, S. P. (2019). The use of budgetary and financial information by politicians in parliament: a case study. Journal of Public Budgeting, Accounting & Financial Management, 31(4), 539–557. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1108/JPBAFM-11-2018-0135

- Kearney, R.-C., Feldman, B. M., & Scavo, C. P. F. (2000). Reinventing government: City managers attitudes and actions. Public Administration Review, 60(6), 535–548. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/0033-3352.00116

- Liguori, M., Sicilia, M., & Steccolini, I. (2012). Some like it non-financial. Public Management Review, 14(7), 903–922. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2011.650054

- Lu, E. Y., & Willoughby, K. (2018). Public performance budgeting: principles and practice. Routledge.

- March, J. G., & Simon, H. A. (1958). Organizations. John Wiley & Sons.

- Motion Jetten. (2019). Kamerstukken 35300, No. 19, 19 September.

- Motion Özturk. (2019). Kamerstukken 35166, No. 12, 3 June.

- Otjes, S. P. (2012). Imitating the newcomer. How, when and why established political parties imitate the policy positions and issue attention of new political parties in the electoral and parliamentary arena: the case of the Netherlands (Doctoral dissertation).

- Patzelt, H., zu Knyphausen-Aufseß, D., & Nikol, P. (2008). Top management teams, business models,and performance of biotechnology ventures: an upper echelon perspective. British Journal of Management, 19(3), 205–221. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8551.2007.00552.x

- Pollitt, C., & Bouckaert, G. (2011). Public management reform. a comparative analysis: new public management, and the neo-Weberian state. Oxford University Press.

- Sinervo, L.-M., & Haapala, P. (2019). Presence of financial information in local politicians’ speech. Journal of Public Budgeting, Accounting & Financial Management, 31(4), 558–577. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1108/JPBAFM-11-2018-0133

- Suzuki, K., & Avellaneda, C. N. (2018). Women and risk-taking behaviour in local public finance. Public Management Review, 20(12), 1741–1767. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2017.1412118

- van Dooren, W., & van de Walle, S.2018). Performance information in the public sector: How it is used. Springer.

- van Helden, J. (2016). Literature review and challenging research agenda on politicians’ use of accounting information. Public Money & Management, 36(7), 531–538. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/09540962.2016.1237162

- van Helden, J., Johnsen, Å, & Vakkuri, J. (2012). Evaluating public sector performance management: the life cycle approach. Evaluation, 18(2), 159–175. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/1356389012442978

- van Helden, J., & Reichard, C. (2019). Making sense of the users of public sector accounting information and their needs. Journal of Public Budgeting, Accounting & Financial Management, 31(4), 478–495. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1108/JPBAFM-10-2018-0124

- Weiss, C. H. (1979). Many meanings of research utilization. Public Administration Review, 39(5), 426–431. DOI: https://doi.org/10.2307/3109916

- Weiss, C. H. (1980). Knowledge creep and decision accretion. Knowledge, 1(3), 381–404. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/107554708000100303