IMPACT

A critical barrier to the large-scale adoption of technology-enabled care services (TECS) remains a lack of evidence around their business cases that would create sufficient value for the stakeholders involved. Drawing on a case study of telecare service delivery, involving public funding and institutions in north east England, the authors highlight the opportunities that technology provides, as well as a series of challenges that need to be addressed. The findings will be particularly helpful for telecare stakeholders, shaping how services are provided.

ABSTRACT

Technology-enabled care services (TECS) are primarily provided in the UK as a public service, using public funds and national systems of health and care. The delivery of such services, however, is increasingly market orientated and subject to many challenges. The authors draw on the literature and case study evidence, to explore the value propositions and value co-creation within TECS, highlighting the challenges and obstacles, as well as possible ways forward.

Introduction

The English NHS, along with local authorities (LAs), is facing an increasingly difficult set of challenges related to the effective planning, commissioning and provisioning of technology-enabled care services (TECS). Even before the Covid-19 pandemic, NHS England’s budget deficit was expected to reach £6 billion by 2020/21 (Gainsbury, Citation2016). Local authority budgets, which include the provision of social care including TECS, have been cut. For example between 2013/2014, and the end of 2019, Newcastle upon Tyne City Council (NCC) has faced cumulative budget cuts of £300 million (Harris, Citation2020b). These constrained budgetary challenges necessitate innovative strategies for more efficient provisioning and delivery of care services. It is anticipated that this can be achieved through leveraging the ‘preventative’ role of digital health technologies and by taking advantage of the rapid development of TECS (Telecare Services Association, Citation2017). TECS allow preventive and early interventions, potentially reducing the cost of care by shifting the focus of care delivery from institutional settings to more community-based and self-directed alternatives (Housing Learning and Improvement Network, Citation2013), and supporting people to remain independent and live in their own homes (Bardsley et al., Citation2011; Public Policy Projects, Citation2020).

During the past two decades, shifts in the UK government policies related to health and social care services have emphasised the importance of a person-centred approach anchored on principles of greater personalization, the maximization of choice and control by the patients (Ferguson, Citation2007; Department of Health, Citation2014). The potential of digital technology-based assisted living services, such as TECS, to address self-directed and complex care needs associated with long-term conditions, such as dementia, is widely acknowledged (Health Committee, Citation2014; Knapp et al., Citation2016). The Covid-19 pandemic affected all areas of public service delivery, making a convincing case for the accelerated adoption of digital technologies in delivering health and social care services (Agostino et al., Citation2021; Leite et al., Citation2020).

Within the context of the changing demographics related to the growing numbers of elderly people, and the associated increasing demand for coping with complex healthcare needs, current research argues that, despite the strategic visions and policy guidance conveyed in UK government publications, the full potential of TECS systems in transforming health and social care services has yet to be realized on a large scale (Barrett et al., Citation2015; May et al., Citation2011; Lennon et al., Citation2017). The evaluation of benefits, differing conceptions of value, and outcome-related effectiveness have often been cited as crucial factors affecting the widespread diffusion and adoption of TECS technologies (Barlow & Hendy, Citation2009; Beale et al., Citation2010; Public Policy Projects, Citation2020).

In the UK, while health and social care services are primarily provisioned as public services, using public funding and national systems of health and care (the NHS and LAs), the delivery of such services is getting increasingly market-oriented (Fotaki, Citation2011; Barron & West, Citation2017) within an economic landscape of ‘mixed-economy of supply’ (Rodrigues & Glendinning, Citation2015). There is also no single model for the provision of healthcare in the UK, with policies and implementation being dependent on centre–local or NHS–local government arrangements in the four nations. Our research focused on TECS in the English context, drawing on relevant policies and research as appropriate. The problem is increasingly viewed as one of the large-scale replication of successful pilots, as opposed to the continued development of localized innovations (PPP, Citation2020).

Furthermore, a lack of coherent and sustainable service business models has been perceived as one of the key barriers to the large-scale adoption and implementations of TECS (May et al., Citation2011; Oderanti & Li, Citation2016; Barlow et al., Citation2012; Bhattacharya, Citation2020). With this in mind, our aim in this article is to draw on theoretical insights, supported by empirical case study research evidence, to identify ways through which future designs of TECS models within England could be shaped.

This article outlines a new theoretical framework, developed in order to examine, interrogate and explain the phenomena of value creation and value realization within a TECS ecosystem. We use an interpretive case study-based approach to report the findings from a recent research study concerning a telecare service delivered by a major provider for social housing—Your Homes Newcastle (YHN). YHN is an ‘arm’s-length management organization’ (ALMO), which was separated from NCC through a management agreement and given the task of managing and improving the housing stock owned by the council (HousingCare, Citation2020). As part of the services that it manages, YHN also provides a community care alarm service (CCAS), branded as ‘Ostara’. To provide this service, YHN works collaboratively with a complex network of stakeholder organizations, including the NHS and its local telehealth provision.

Conceptualizing TECS ecosystems

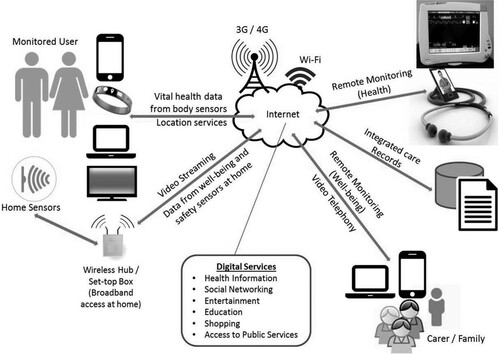

A typical telecare system uses a range of electronic devices (with sensors) and a base unit installed in a user’s home (or worn by the user), which are connected to a remote monitoring centre through a telecommunications network—see . These sensors monitor vital health/activity indicators for vulnerable users (such as falls) and also monitor the environment in their home (such as detection of flooding, gas leaks, smoke or fire). In case of emergencies, these sensors trigger alarms (automatically or through manual action by the user) and send alerts to a remote telecare monitoring centre. The telecare call centre, in turn, acknowledges the alarm and responds appropriately following protocol established as part of the service agreement.

Figure 1. Basic monitoring and response for telecare. Source: Adapted from Brownsell and Bradley (Citation2003, p. 8).

A similar technological configuration to telecare may also be used for telehealth systems—for remote home monitoring and diagnosis of vital health signs, patterns and health analytics. ‘TECS’ is a term is used to refer either to telecare or telehealth systems individually or, in more sophisticated cases, when they are used in some form of combination. The predominant communications technology used for telecare are analogue telephone network connections (pull cords, fall sensors, speakers and call centres), whereas telehealth may make greater use of digital technologies that are primarily mobile in character. illustrates a typical TECS delivery model for remote monitoring of health and wellbeing.

In addition to the TECS provider, the service delivery architecture potentially involves a wide range of stakeholder organizations:

Commissioners of adult social care services (LAs).

Commissioners of health services, i.e. NHS clinical commissioning groups (CCGs).

Providers of other public services (such as ambulance and fire services).

Providers of housing services.

Providers of other care services, for example homecare services.

Health organizations, for example GPs, district nurses and hospitals.

Partners and collaborators within the TECS industry such as vendors, solution providers and the Telecare Services Association (TSA).

TECS have been described by Sugarhood et al. (Citation2014) as a complex and diverse ‘user system’ in which aligning interests across a wide range of stakeholders remains critical yet challenging. We argue that the TECS architecture may be better appreciated as a business and service ecosystem.

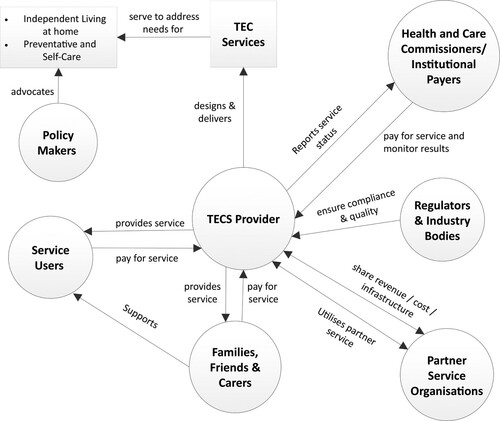

The metaphor of a ‘business ecosystem’ has been widely used in the academic literature to represent a loosely-bound community of interacting entities (actors) with varying roles and capabilities, with their relationships determining the overall effectiveness at an aggregated level (Iansiti & Levien, Citation2004; Moore, Citation1993). Such a metaphor provides a useful lens to adopt a systemic view when exploring issues related to participation, partnerships and collaboration within the broader business environment (Adner, Citation2017). It has been argued that investigating TECS requires the adoption of a systems thinking approach (Chughtai & Blanchet, Citation2017), to capture the complexity of relationships and interactions, and diversity of the loosely coupled communities of associated actors that are defined by their networks and affiliations, rather than being part of a rigid, hierarchical structure (Adner, Citation2017). Adopting an ecosystem approach provides a way of conceptualizing the complex healthcare landscape—see —and allows new opportunities for the development and adoption of service models. In the next section, we argue that new perceptions and realizations of what constitutes value in the healthcare economy are critical to harnessing the potential of new technology-based care solutions and innovations to provide these new forms and types of value towards the development of user-centric care models.

As illustrated in , a TECS ecosystem and infrastructure requires a much deeper level and richness of collaboration between key stakeholders such as policy-makers, service providers, commissioners, regulators, technology vendors, service users and carers (families and beneficiaries). Such collaboration will necessitate a value-driven approach when examining the TECS model, to ensure that the interests and incentives of all stakeholders are effectively accommodated and aligned.

It is important to note that TECS within the English health and social care context entail different objectives, separate funding mechanisms, and discrete organizational stakeholders. Telecare services are funded and provisioned as part of adult social care services by LAs, whereas telehealth services are funded and delivered by NHS England, primarily led by clinicians and health professionals. The current policy narrative around TECS (NHS England, Citation2014) promotes an integrated and holistic care agenda that aims to blur the boundaries between social care and healthcare, emphasising the need for ‘independent living technologies together with life-enhancing technologies’ (Turner & McGee-Lennon, Citation2013). In this article, the descriptions of TECS stakeholders are mostly restricted to telecare services and local government. Such a narrowing is largely because telehealth initiatives in the UK are still emerging and not widely adopted, and such services are restricted to clinical settings of NHS England.

A service business model for TECS

The contemporary literature on public management theory and practice highlights the experiential, collaborative and systemic nature of public service delivery (Radnor et al., Citation2014; Osborne et al., Citation2016). The critical role of relational capital-based social marketing practices to facilitate co-creation in public services has been increasingly acknowledged (McLaughlin et al., Citation2009). Accordingly, our research brings together two interdisciplinary and complementary theoretical frames, synthesizing the existing literature on business models and service innovation to propose a new conceptualization of value.

The conceptualization of a TECS ecosystem reflects a complex sociotechnical innovation (Sugarhood et al., Citation2014) where the sharing of risks and the alignment of interests and incentives across a diverse range of stakeholders is critical (Christensen & Remler, Citation2009). Therefore, a transformation agenda to harness the potential of technology-enabled care solutions and innovations needs to take a value-driven approach (Porter & Lee, Citation2013), in order to effectively capture the complexity of relationships and interactions, and the diversity of the connected social and economic actors (Lusch & Nambisan, Citation2015). Such an approach demands a new way of conceptualizing value propositions and opportunities for value co-creation for all the stakeholders within a service ecosystem.

Conventional business model based thinking espouses a narrow role for the customer in the value creation process and emphasises the realization of value, primarily in economic terms (Afuah & Tucci, Citation2001). While such monetization aspects are vital for designing sustainable TECS models, it remains equally important that these services follow a ‘public ethos’ (Boyne, Citation2002), with due attention being placed on intangible social benefits such as wellbeing and the quality of life (Lluch, Citation2013; Goodwin, Citation2010). This necessitates adopting a broader conceptualization of value, incorporating commercial self-interest, public interest and procedural interest as the fundamental bases of public value creation (Talbot, Citation2011).

A value-driven approach: business model based thinking

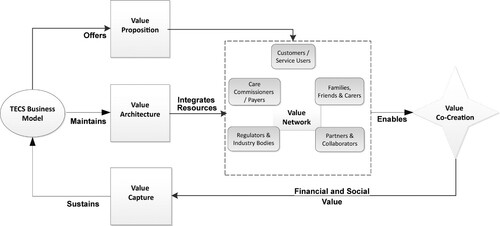

Business model driven thinking has predominantly been applied to ‘traditional’ commercial business sectors and digital businesses (Baden-Fuller & Haefliger, Citation2013; Zott et al., Citation2011). Business models are conceptualized as the underlying core economic logic and strategic choices that explain how an organization could create and deliver value to its customers and network of partners (Magretta, Citation2002; Chesbrough & Rosenbloom, Citation2002) and, importantly, can capture value within the ‘value network’ or ‘activity system’ of the business (Shafer et al., Citation2005; Zott & Amit, Citation2010). While there are divergent views on what constitutes a business model, in this article we adopt a framework developed by Al-Debei and Avison (Citation2010), which identifies four components of a business model:

Value proposition: how an organization creates value for its customers through customer-based products or service offerings (Osterwalder et al., Citation2005).

Value architecture: physical resources, such as technology infrastructure and assets; organizational forms and practices, as well as human resources employee skills; a knowledge base that needs to be configured and organized in a manner to facilitate a competitive value proposition (Hedman & Kalling, Citation2003; George & Bock, Citation2011).

Value network: those cross-organizational collaborations, partnerships, and relationships necessary to create and deliver value (Shafer et al., Citation2005; Teece, Citation2010).

Value realization: the revenue-earning logic to be profitable (or sustainable) and the monetization aspects of a business model.

Re-conceptualizing value co-creation in TECS

‘Value’ is one of the most ill-defined and elusive concepts in the academic literature (Grönroos & Voima, Citation2013). Conventional business model based thinking emphasises the realization of value, primarily in economic terms of traditional, through a revenue logic that defines ‘how a company makes money’ (Afuah & Tucci, Citation2001). While such monetization aspects are integral to designing sustainable TECS models, a reconceptualization of value might be necessary to accommodate the non-financial, intangible elements linked with healthcare services. For instance, there would be a much greater emphasis on citizens’ wellbeing support for independent living and quality of life measures, as well as contributions to better ‘lived’ experience at social/society and community organization levels (Greenhalgh et al., Citation2013).

Traditionally, business model based thinking adopts a narrower role of customers in the value proposition and/or value creation process that views customers ‘as part of a commercial segment’ (Chesbrough & Rosenbloom, Citation2002). The majority of TECS users are older adults with physical, cognitive, and sensory limitations; and perceiving such vulnerable people as being fully informed, empowered, and rational consumers could be problematic (Daly, Citation2012). Research on service innovation, grounded on service-dominant logic (Vargo & Lusch, Citation2004), would indicate there are viable alternatives to financially orientated business model thinking. Service-dominant logic offers some useful insights that espouse a broader, systemic level of engagement with service users (and other stakeholders) in the co-creation of value that emphasises social as well as economic factors through the integration of stakeholder resources within the entire service ecosystem (Vargo & Lusch, Citation2008).

In pursuit of innovation in healthcare services, patient-centric care is considered as a major transformative goal (Berry & Bendapudi, Citation2007; Bitner & Brown, Citation2008). The themes of patient (or user) engagement and empowerment have drawn increasing attention in the academic literature (Badcott, Citation2005; Armstrong et al., Citation2013) and policy discourses, with advocacy emerging around ‘patient-centric care’ service design (NHS, Citation2014). Service innovation thinking and concepts could provide a complementary way to examine and develop new business models that embraces the ideas of user-centric, ‘co-production’ and value creation through ‘combinative resource configuration’ (Joiner & Lusch, Citation2016; McColl-Kennedy et al., Citation2012; Nambisan & Nambisan, Citation2009; Wherton et al., Citation2015). Such an integrated approach could potentially broaden the application possibilities of business model thinking in social care and healthcare services, through infusing service logic into designs of new TECS business models that are focused on the needs of users, other stakeholders, and are also adaptive to their organizational, social and political contexts (Greenhalgh et al., Citation2016).

Healthcare services often fail to achieve patient (user)-centric value creation owing to health policies that are focused on costs and efficiency improvements (Wildavsky, Citation1977; Wenzl et al., Citation2017). While business model based thinking focuses on the configuration of organizational resources to maximize efficiency gains, a customer- (user) centric and relational view of service logic is complementary by affirming the importance of achieving effectiveness over efficiency gains (Lusch & Vargo, Citation2014).

Following the above arguments, we bring together perspectives from two distinct, yet complementary, theoretical domains to develop a conceptual framework (). The framework illustrates how different components of a TECS business model work together in proposing and co-creating value, as well as capturing part of the created value. We use this framework as the basis of a case study research of a social housing provider of telecare services, YHN, as outlined below.

Methodology

We used a single exploratory case study design, with an interpretive focus (Stake, Citation1995; Walsham, Citation2006) to investigate and analyse a TECS, embedded within its complex social, organizational, and technological contexts (Baker, Citation2011; Greenhalgh et al., Citation2016).

The Case

YHN, an ALMO, is a private company, limited by guarantee, wholly controlled by NCC. YHN acts as an umbrella organization for the delivery of TECS to around 3000 local residents, under the Ostara brand name through Abri Trading Ltd, which was constituted as a separate subsidiary company to facilitate the commercial activities undertaken in the business. YHN has published accounts stating an income of £36.3 million for the year to March 2019, with operating costs of £40.9 million producing losses of £5.76 million. YHN has a headcount of 678 FTEs.

Historically, Ostara was heavily reliant on the council’s financial support when delivering telecare services to the majority of its customers who were assessed by the council’s adult social care department as having an eligible care need for telecare and meeting a pre-defined financial eligibility criterion. Cuts in public funding, at both national and regional levels, affected Ostara’s budget for supporting adult social care services (Phillips & Simpson, Citation2017), with the LA’s 2016/17 budget proposal including a recommendation to remove funding support to Ostara, starting from the middle of 2016.

Ostara’s viability was perceived to be at risk by YHN management who needed to look for ways to keep the service both financially viable and self-sustaining. In 2017, the total operational expenditure, with full cost recovery, for Ostara was in the order of £1.6 million with an operational workforce of just over 20 FTE (full-time equivalent) staff. Service reviews estimated that due to cuts in government and council subsidies there would need to be a reduction in FTE headcount, as well as up to a 30% increase in the client base, if the service was to remain financially sustainable with adequate service level provision. This is set against an ageing Newcastle upon Tyne population. The current percentage of the population aged 65 or over is expected to rise by a third by 2030 from its current level of 15.6%, and the number of over 85-year-olds to rise to over 8000 by 2029 (Tewdwr-Jones et al., Citation2015). Within Newcastle upon Tyne, the predicted numbers of hospital admissions due to falls (aged 65+) are projected as rising to 1,737 annually from 1,440 in 2020, with 12,750 predicted to have a fall in 2021 rising to 13,915 in 2030 (Institute of Public Care, Citation2020). The provision of TECS is seen as being a key component of a preventative public health strategy to decrease the number of falls for residents age over 65, thereby decreasing hospital admissions and pressure on local NHS and care services. This demographic and healthy living independently at home strategy is set against a massive funding reduction for NCC, which has borne over £300 million of government budget cuts between 2010 to 2020 with a further £45 million annual funding gap being forecast over the next three years to 2023 (Harris, Citation2020a). This gap has been further exacerbated by the Covid-19 pandemic.

These cuts stand in stark contrast to the aspirations of NCC. Newcastle and Gateshead’s CCG operational plan for 2019/2020 states that ‘prevention is key to reducing health inequalities and this prevention agenda runs through all themes’ (Newcastle Gateshead Clinical Commissioning Group, Citation2019), while the North East and North Cumbria Integrated Care System’s vision is ‘to transform health outcomes for people and help them to live longer, healthier and wealthier lives’. The Newcastle/Gateshead integrated care partnership covers a population of 498,261 people. Within this, the sustainability and transformation five-year plan to 2023 focuses on localities of 30,000 to 50,000 people where aspirations are for the integration of general practice, community services, social care and the voluntary sectors with enhanced partnerships working between the NHS and local government. Health and wellbeing in Newcastle are caught in a cycle of inequality, in which ill-health combines with social-economic exclusion to undermine the productivity and growth of the city’s economy. Hence, there is an urgent need for new service models which are prevention orientated and person-centric to provide the adult population with independent and fulfilling lives. The anticipated patient/service-user benefit and impact would be that people are able to stay healthier longer in their own homes, thereby helping to avoid unnecessary hospital and care home admissions. In order to achieve this, it is forecast that, by 2030, the region will need an additional 15,000 staff at a cost of £550 million across the NHS North Cumbria and North East Integrated Care System (ICS). This despite a current ageing workforce in 2019/20, where 20% are over 55 and 50% are over 45 years of age.

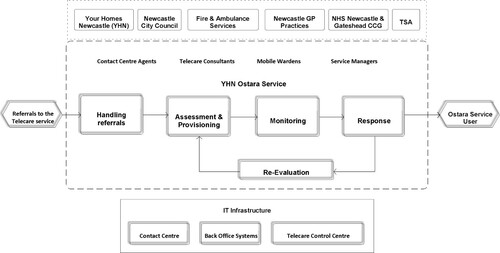

Ostara employs a telecare technology infrastructure and management platform provided by Jontek. Answerlink connects a range of electronic devices (with sensors) including alarm units, pendants, fall detectors, bed occupancy sensors, medication dispensers, door exit sensors, and flood detectors, installed at the service user’s home to the Ostara control centre. The service aims to monitor vital health status (for example falls) for elderly community members and to monitor the environment at their home (for example smoke detection or gas leaks) to assist with the safe, secure and independent living of the people. Ostara is accredited by the UK Telecare Services Association (TSA) and follows their code of practice. Ostara’s processes are aligned with the TSA prescribed ‘Reference to Response’ (R2R) service model for telecare service providers. These processes cover five essential elements: handling referrals; assessment and provisioning; monitoring; response; and re-evaluation within the overall service delivery cycle—see .

Data collection and analysis

We engaged with YHN during the early months of 2016 in order to conduct an empirical investigation of Ostara’s services. Our collection of empirical data, both qualitative and quantitative, primarily comprised of interviews, documentary evidence and observational field notes—see .

Table 1. Sources and methods for data collection.

Transcriptions of the interviews with Ostara staff members generated a large volume of data (approximately 200 pages of transcript). To analyse the large volume of interview data that potentially can be an ‘attractive nuisance’ (Miles, Citation1979), we used NVivo, primarily to organize the interview transcript text, and to supplement our interpretative processes followed by manual coding.

Findings and discussion

This section presents the key findings from the study. The analysis of data suggests the vital role of factors related to the organizational context in which Ostara is embedded. Contextual issues such as identity and culture, how Ostara is governed, and its relationship with the LA shape the management decisions around the provisioning and delivery of Ostara. The challenges to the financial viability of the service emerged as another central theme in the analysis. It is also interesting to note how the Ostara’s organizational dynamics affect the opportunities for growth and sustainability of the service.

Ostara delivers valuable assisted living support to over 3,000 elderly and vulnerable residents and is available 24 hours a day throughout the year. At the time of conducting this study, the leading priority for YHN management was to keep the service viable by putting in place short-term measures targeted at retaining its existing customers, acquiring new customers through promotions of the refashioned service brand, and reducing operational costs through efficiency gains. The challenges facing the service were multifaceted, and so too were the potential solutions to achieve future sustainability for the service.

In order to ensure the future sustainability for this service, the current service model needs to be developed to offer service packages that attract more self-funded customers. Such a transformation of the Ostara service model would demand that several issues are addressed: investment to upgrade the technology used; establish strategic collaborations and partnerships; and, cultural change within the organization to embrace a more commercial outlook. All these conditions require planning for future scenarios and making strategic decisions about the business, although the analysis of data suggests a perceived lack of independence and control for the Ostara service management. Therefore, the prospects of a transformation for the service could be considered low, given the prevailing complicated relationship between YHN and the LA and the harsh political landscape in which Ostara operates.

The empirical findings can be examined by using the key theoretical constructs of a service business model comprising value proposition, value co-creation and value realization. This highlights how TECS provider organizations may be able to reframe their value propositions and to co-produce value in a sustainable service ecosystem, through innovative configurations of their internal, as well as network, resources accessible via partnerships and collaborations.

Poor value propositions

One of the major issues concerns the availability of choices on levels of service (or packages) for users of the services. The reactive usage of telecare solutions to provide ‘peace of mind’ in the event of an emergency is not aiding customers’ value perception of the service (Johnson et al., Citation2008). Our analysis further suggests that the current range of service offerings are not addressing the more diverse, meaningful, and life-enhancing needs of specific customer segments and, thus, lack unique value propositions for them (Magretta, Citation2002; Osterwalder et al., Citation2005).

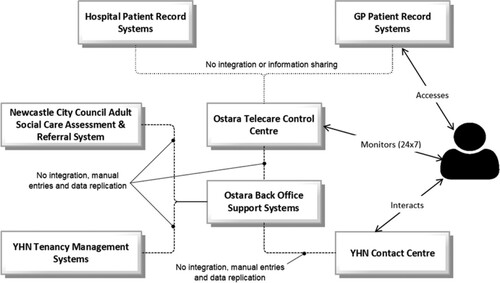

The existing literature acknowledges the vital role for social and relational marketing efforts in encouraging healthcare technology adoption (McGuire, Citation2012; Wright & Taylor, Citation2005), but this appears to be missing in our case. Due to a lack of integration among several disparate IT systems involved in the service—see —there is a limited value proposition of the service to other stakeholders in the service ecosystem. For example, sharing of useful information about the users of the service (for example falls history) with the concerned GP and/or hospitals could provide the relevant stakeholders from the health system with critical insights into the risk profiles of their patients, enabling their assessment and determination of appropriate preventative and proactive actions. However, YHN’s heavy reliance on NCC for its technology infrastructure—IT system upgrades and skill development—presents a significant challenge amidst the council’s frequent budget cuts to its ICT infrastructure.

Missing opportunities for value co-creation in the service ecosystem

The literature on business models and service logic suggests that value co-creation in the service ecosystem happens through the integration of interactional resources (Akaka & Vargo, Citation2014). Such co-creation relates to all the participating actors in an ‘activity system’ (Zott & Amit, Citation2010) that forms a ‘value constellation’ (Normann & Ramirez, Citation1993). From a TECS provider’s standpoint, interactional resources (for example information infrastructure and governance, skills, and knowledge of the staff), business processes and policies, relationships with NCC and other partners are vital constituents of its value architecture (Al-Debei & Avison, Citation2010).

Our analysis found that Ostara has demonstrated only token interactions between the service provider and with the NHS or other health organizations. While the provider maintains mutually beneficial relationships with other public services—fire, ambulance, and housing services—the interactions mostly relate to reciprocal signposting /referrals and the absence of formal collaborative partnerships in the delivery of TECS. The lack of such collaboration points to a weak value network and challenges the co-creation of value in the service ecosystem. Future technology trends suggest the availability of a superior broadband infrastructure providing improved network connectivity and access to users (Frontier Economics, Citation2017) and also the proposed (and planned) changeover to digital networks from the current analogue system in England (McCaskil, Citation2018). Such a change could potentially alter the technological landscape for the TEC services through opportunities for innovative service designs and new value co-creation within the service ecosystem.

Several interviewees voiced a perceived need for more investment in IT infrastructure—both hardware (for example handheld tablet devices for field staff) and software upgrades—to facilitate better and faster information flows across the organizational network. The lack of integration among disjointed IT systems (see ) presents significant challenges to the YHN management’s aim of enhancing the productivity of its staff given the high volume of manual paperwork, and the effort spent in duplicating information across multiple IT systems. Furthermore, a robust information infrastructure with integrated IT systems could potentially enable the flow of vital information across YHN and facilitate strategic and operational decision-making processes, contributing to the success of Ostara (Collinge & Liu, Citation2009). On a broader service ecosystem level, an integrated IT infrastructure and effective information governance that supports interoperability, data sharing and integration of information systems, are critical to driving collaboration and partnerships across health and social care organizations (Waring & Wainwright, Citation2015).

Inadequate realization of value from the services

The literature on business models emphasises the monetization of value from services through various revenue streams (Osterwalder et al., Citation2005), as well as the importance of the role of profit or surplus generation to the growth and sustainability of the service (Johnson et al., Citation2008). Data from our case study suggests that organizational constraints such as a lack of commercial focus, and rigid procurement policies and guidance of LAs do not favour the telecare service providers in terms of maximizing their revenue sources and also, managing their cost structure to compete effectively in the market.

Our research demonstrates that a ‘lack of evidence’ remains one of the critical challenges in advocacy and acquiring appropriate funding from institutional authorities. Given that most of the evidence relies on anecdotal information, the absence of ‘hard’ financial and operational evidence on cost savings, the value proposition of TECS remains questionable (Henderson et al., Citation2014). The overall value created by TECS should not only be measured in tangible and economic measures but also in the form of long-term benefits that can be measured using intangible social measures such as the wellbeing of citizens, support for independent living and better quality of life (Schwamm, Citation2014; Lluch, Citation2013; Goodwin, Citation2010). However, the lack of effort in developing such measures can be attributed to several operational challenges for service providers such as their limited resources, inadequate infrastructure and lack of incentives. This calls for innovation in existing evidence collection methods, facilitated by education and training in evidence-based approaches to management and policy-making for relevant stakeholders (Wainwright et al., Citation2018).

Social business model designs, with a ‘profit with purpose’ mission (Osterwalder & Pigneur, Citation2011), need to accommodate a type of ‘social profit equation’ as well as an ‘economic profit equation’ (Yunus et al., Citation2010, p. 319). It can also be argued that social contributions could be a part of the demonstrable evidence base that offers additional value propositions to the commissioners and other institutions and facilitate attracting funding support for the service. Capturing social value as generated in the service must be used together with effective mechanisms and tools for assessment, such as social return on investment (SROI) that allows reporting both tangible economic and intangible social benefit value (Nicholls et al., Citation2009; Millar & Hall, Citation2013). However, as Triantafillou (Citation2020) noted, putting such value assessment systems demand considerable resources and can be cost prohibitive.

Conclusion

The contemporary discourse on innovation and transformation in public services, which includes healthcare, emphasises the need for value co-production through various forms of user participation and engagement in the service design and implementation processes (Osborne et al., Citation2016; Wherton et al., Citation2015). Shah et al. (Citation2019), in their review of a project to enable the co-development of an integrated health and social care infrastructure, conclude that health and social care information is not only highly complex, but often socially and personally sensitive in ways that do not apply in other domains. This, therefore, requires a tailored inter-disciplinary and inter-sectoral approach to technology development. This directly applies to any future TECS systems and infrastructure design where information collection and sharing is integral for any successful operation.

We adopted an ecosystem approach to investigate the complex sociotechnical landscape of a TECS operating in north east England and to capture the complexity of relationships and interactions among a diverse set of stakeholders. Drawing on the conceptualizations of value from the literature (Al-Debei & Avison, Citation2010; Vargo & Lusch, Citation2004), we have developed an investigative framework to inform our field research. In the form of an exploratory case study, we analysed the challenges as well as opportunities for value propositions, co-creations and sustainability within a TECS ecosystem. Our findings reiterate the vital role played by collaborations and partnerships in a service ecosystem, in which relational, experiential, ethical and social aspects are accommodated by the aspirational role of technology designs (Flick et al., Citation2020).

The global Covid-19 pandemic created a new set of complex economic and social challenges for the delivery of health and social care services (Kimpen & Osnabrugge, Citation2020), in which the ‘new normal’ is anticipated to accelerate digital transformation of public services, especially in health and social care (Agostino et al., Citation2021; Leite et al., Citation2020; Public Policy Projects, Citation2020). Our research contributes towards the ongoing conversations and debates by suggesting how, derived from a value-centric analysis of a TECS ecosystem, changes are necessary to how services are provided through adopting a more creative and innovative approach to service provision (Cluley & Radnor, Citation2020).

While the findings from our case are context-bound, derived from a set of specific problems in north east England, it is possible that the insights gained from our investigation can be applied, with appropriate adjustments, to studying similar service models located elsewhere. These other settings will, however, be characterized by a mixed economy of service provisions.

Further research building on our analysis is possible. The boundary of TECS ecosystems can be expanded to include the regional and national health organizations (for example CCGs, GP practices and Public Health England) and TECS industry representatives. Amidst the overarching policy visions and national initiatives promoting collaborative working between health and social care (NHS England, Citation2017), our ecosystem approach emphasises the critical need for viewing telecare and telehealth together. Such a broadened scope of research will allow future studies to examine the barriers, as well as opportunities of widespread adoption, value co-creation and sustainability within the integrated care pathways (Chrysanthaki et al., Citation2013), and how this can be embedded within the TECS ecosystems.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Your Homes Newcastle for their support when undertaking the case study, as well as for their comments on an earlier version of this article. We are also grateful to the constructive comments made by the reviewers. All errors remain the responsibility of the authors.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Adner, R. (2017). Ecosystem as structure: an actionable construct for strategy. Journal of Management, 43(1), 39–58. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206316678451

- Afuah, A., & Tucci, C. L. (2001). Internet business models and strategies: Text and cases. McGraw-Hill Higher Education.

- Agostino, D., Arnaboldi, M., & Lema, M. D. (2021). New development: COVID-19 as an accelerator of digital transformation in public service delivery. Public Money & Management, 41(1), 69–72. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/09540962.2020.1764206

- Akaka, M. A., & Vargo, S. L. (2014). Technology as an operant resource in service (eco) systems. Information Systems and e-Business Management, 12(3), 367–384. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10257-013-0220-5

- Al-Debei, M. M., & Avison, D. (2010). Developing a unified framework of the business model concept. European Journal of Information Systems, 19(3), 359–376. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/ejis.2010.21

- Armstrong, N., Herbert, G., Aveling, E. L., Dixon-Woods, M., & Martin, G. (2013). Optimizing patient involvement in quality improvement. Health Expectations, 16(3), e36–e47. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/hex.12039

- Badcott, D. (2005). The expert patient: valid recognition or false hope? Medicine, Healthcare and Philosophy, 8(2), 173–178. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11019-005-2275-7

- Baden-Fuller, C., & Haefliger, S. (2013). Business models and technological innovation. Long Range Planning, 46(6), 419–426. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2013.08.023

- Baker, G. R. (2011). The contribution of case study research to knowledge of how to improve quality of care. BMJ Quality & Safety, 20(Suppl 1), i30–i35. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs.2010.046490

- Bardsley, M., Billings, J., Chassin, L., Dixon, J., Eastmure, E., Georghiou, T., Lewis, G., Vaithianathan, R., & Steventon, A. (2011). Predicting social care costs: a feasibility study. Retrieved from: https://www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk.

- Barlow, J., Curry, R., Chrysanthaki, T., Hendy, J., & Taher, N. (2012). Developing the capacity of the remote care industry to supply Britain’s future needs. Retrieved from: www.haciric.org.

- Barlow, J., & Hendy, J. (2009). Adopting integrated mainstream telecare services. Chronic Disease Management and Remote Patient Monitoring, 15(1), 8.

- Barrett, D., Thorpe, J., & Goodwin, N. (2015). Examining perspectives on telecare: factors influencing adoption, implementation, and usage. Smart Homecare Technology and TeleHealth, 3, 1–8. DOI: https://doi.org/10.2147/SHTT.S53770

- Barron, D. N., & West, E. (2017). The quasi-market for adult residential care in the UK: do for-profit, not-for-profit or public sector residential care and nursing homes provide better quality care? Social Science & Medicine, 179, 137–146. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.02.037

- Beale, S., Truman, P., Sanderson, D., & Kruger, J. (2010). The Initial Evaluation of the Scottish Telecare Development Program. Journal of Technology in Human Services, 28(1-2), 60–73. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/15228831003770767

- Berry, L. L., & Bendapudi, N. (2007). Healthcare a fertile field for service research. Journal of Service Research, 10(2), 111–122. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670507306682

- Bhattacharya, S. (2020). Designing value creasing and sustainable business models: An investigation of telehealthcare services in North-east England. Unpublished PhD, Northumbria University, Newcastle.

- Bitner, M. J., & Brown, S. W. (2008). The service imperative. Business Horizons, 51(1), 39–46. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2007.09.003

- Boyne, G. A. (2002). Public and private management: what’s the difference? Journal of Management Studies, 39(1), 97–122. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6486.00284

- Brownsell, S., & Bradley, D. (2003). Assistive technology and telecare: forging solutions for independent living. Policy Press.

- Chesbrough, H., & Rosenbloom, R. S. (2002). The role of the business model in capturing value from innovation: evidence from Xerox Corporation's technology spin-off companies. Industrial and Corporate Change, 11(3), 529–555. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1093/icc/11.3.529

- Christensen, M. C., & Remler, D. (2009). Information and communications technology in US healthcare: why is adoption so slow and is slower better? Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law, 34(6), 1011–1034. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1215/03616878-2009-034

- Chrysanthaki, T., Hendy, J., & Barlow, J. (2013). Stimulating whole system redesign: lessons from an organizational analysis of the Whole System Demonstrator programme. Journal of Health Service Research Policy, 18(1 Suppl), 47–55. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/1355819612474249

- Chughtai, S., & Blanchet, K. (2017). Systems thinking in public health: a bibliographic contribution to a meta-narrative review. Health Policy and Planning, 32(4), 585–594. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czw159

- Cluley, V., & Radnor, Z. (2020). Rethinking co-creation: the fluid and relational process of value co-creation in public service organizations. Public Money & Management, 1–10. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/09540962.2020.1719672

- Collinge, W. H., & Liu, K. (2009). Information architecture of a telecare system. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare, 15(4), 161–164. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1258/jtt.2008.008009

- Daly, G. (2012). Citizenship, choice and care: an examination of the promotion of choice in the provision of adult social care. Research, Policy and Planning, 29(3), 179–189.

- Department of Health. (2014). Personalized health and care 2020. HMSO.

- Ferguson, I. (2007). Increasing user choice or privatizing risk? The antinomies of personalization. British Journal of Social Work, 37(3), 387–403. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcm016

- Flick, C., Zamani, E. D., Stahl, B. C., & Brem, A. (2020). The future of ICT for health and ageing: Unveiling ethical and social issues through horizon scanning foresight. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 155, 119995. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2020.119995

- Fotaki, M. (2011). Towards developing new partnerships in public services: users as consumers, citizens and/or co-producers in health and social care in England and Sweden. Public Administration, 89(3), 933–955. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9299.2010.01879.x

- Frontier Economics. (2017). Future benefits of broadband networks. Retrieved from: https://nic.org.uk/app/uploads/Benefits-analysis.pdf.

- Gainsbury, S. (2016). Feeling the crunch: NHS finances to 2020. Nuffield Trust.

- George, G., & Bock, A. J. (2011). The business model in practice and its implications for entrepreneurship research. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 35(1), 83–111. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2010.00424.x

- Goodwin, N. (2010). The state of telehealth and telecare in the UK: prospects for integrated care. Journal of Integrated Care, 18(6), 3–10. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5042/jic.2010.0646

- Greenhalgh, T., Shaw, S., Wherton, J., Hughes, G., Lynch, J., Hinder, S., & Sorell, T. (2016). SCALS: a fourth-generation study of assisted living technologies in their organizational, social, political and policy context. BMJ open, 6(2), e010208. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010208

- Greenhalgh, T., Wherton, J., Sugarhood, P., Hinder, S., Procter, R., & Stones, R. (2013). What matters to older people with assisted living needs? A phenomenological analysis of the use and non-use of telehealth and telecare. Social Science & Medicine, 93, 86–94. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.05.036

- Grönroos, C., & Voima, P. (2013). Critical service logic: making sense of value creation and co-creation. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 41(2), 133–150. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-012-0308-3

- Harris, J. (2020a). Austerity is grinding on—it has cut too deep to ‘level up’. The Guardian, 10 February. Retrieved from: www.theguardian.com.

- Harris, J. (2020b). The pandemic has exposed the failings of Britain’s centralised state. The Guardian, 25 May. Retrieved from: www.theguardian.com.

- Health Committee. (2014). Managing the care of people with long-term conditions. HC 401 2014-15. HMSO.

- Hedman, J., & Kalling, T. (2003). The business model concept: theoretical underpinnings and empirical illustrations. European Journal of Information Systems, 12(1), 49–59. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.ejis.3000446

- Henderson, C., Knapp, M., Fernández, J.-L., Beecham, J., Hirani, S. P., Beynon, M., … Newman, S. P. (2014). Cost-effectiveness of telecare for people with social care needs: the Whole Systems Demonstrator cluster randomised trial. Age and Ageing, 43(6), 794–800. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afu067

- Housing Learning and Improvement Network. (2013). Assisted Living Platform—The Long Term Care Revolution [online]. Retrieved from: https://www.housinglin.org.uk.

- HousingCare. (2020). Arms Length Management Organizations. Retrieved from: https://housingcare.org/resources/.

- Iansiti, M., & Levien, R. (2004). Strategy as ecology. Harvard Business Review, 82(3), 68–81.

- Institute of Public Care. (2020). Projecting older people population information. Retrieved from: www.poppi.org.uk.

- Johnson, M. W., Christensen, C. M., & Kagermann, H. (2008). Reinventing your business model. Harvard Business Review, 86(12), 57–68.

- Joiner, K. A., & Lusch, R. F. (2016). Evolving to a new service-dominant logic for healthcare. Innovation and Entrepreneurship in Health, 3, 25–33. DOI: https://doi.org/10.2147/IEH.S93473

- Kimpen, J., & Osnabrugge, R. (2020). Moving towards value-based care: Will COVID-19 accelerate or slow down transformation? Retrieved from: https://www.philips.com/.

- Knapp, M., Barlow, J., & Comas-Herrera, A. (2016). The case for investment in technology to manage the global costs of dementia. PIRU Publication.

- Leite, H., Hodgkinson, I. R., & Gruber, T. (2020). New development: ‘Healing at a distance’—telemedicine and COVID-19. Public Money & Management, 40(6), 483–485. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/09540962.2020.1748855

- Lennon, M. R., Bouamrane, M.-M., Devlin, A. M., O'Connor, S., O'Donnell, C., Chetty, U., … Finch, T. (2017). Readiness for delivering digital health at scale: lessons from a longitudinal qualitative evaluation of a national digital health innovation program in the United Kingdom. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 19(2), e42. DOI: https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.6900

- Lluch, M. (2013). Incentives for telehealthcare deployment that support integrated care: a comparative analysis across eight European countries. International Journal of Integrated Care, 13, 4. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5334/ijic.1062

- Lusch, R. F., & Nambisan, S. (2015). Service innovation: a service-dominant logic perspective. MIS Quarterly, 39(1), 155–175.

- Lusch, R. F., & Vargo, S. L. (2014). Service-dominant logic: premises, perspectives, possibilities. Cambridge University Press.

- Magretta, J. (2002). Why business models matter. Harvard Business Review, 80(5), 86–92.

- May, C. R., Rogers, A., Wilson, R., Mair, F. S., Finch, T. L., Cornford, J., & Robinson, A. L. (2011). Integrating telecare for chronic disease management in the community: what needs to be done? BMC Health Services Research, 11(1), 131–131. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-11-131

- McCaskil, S. (2018, April 20). BT's plans to switch off analogue phone network gather momentum. Retrieved from: https://www.techradar.com

- McColl-Kennedy, J. R., Vargo, S. L., Dagger, T. S., Sweeney, J. C., & Kasteren, Y. V. (2012). Healthcare customer value cocreation practice styles. Journal of Service Research, 15(4), 370–389. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670512442806

- McGuire, L. (2012). Slippery concepts in context: relationship marketing and public services. Public Management Review, 14(4), 541–555. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2011.649975

- McLaughlin, K., Osborne, S. P., & Chew, C. (2009). Relationship marketing, relational capital and the future of marketing in public service organizations. Public Money & Management, 29(1), 35–42. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/09540960802617343

- Miles, M. B. (1979). Qualitative data as an attractive nuisance: the problem of analysis. Administrative Science Quarterly, 24(4), 590–601. DOI: https://doi.org/10.2307/2392365

- Millar, R., & Hall, K. (2013). Social return on investment (SROI) and performance measurement: the opportunities and barriers for social enterprises in health and social care. Public Management Review, 15(6), 923–941. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2012.698857

- Moore, J. F. (1993). Predators and prey: a new ecology of competition. Harvard Business Review, 71(3), 75–83.

- Nambisan, P., & Nambisan, S. (2009). Models of consumer value cocreation in healthcare. Healthcare Management Review, 34(4), 344–354. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/HMR.0b013e3181abd528

- Newcastle Gateshead Clinical Commission Group. (2019). Operational plan 2019/20. Retrieved from: https://www.newcastlegatesheadccg.nhs.uk.

- NHS England. (2014). The NHS five year forward view.

- NHS England. (2017). NHS moves to end ‘fractured’ care system’. https://www.england.nhs.uk.

- Nicholls, J., Cupitt, S., & Durie, S. (2009). A guide to social return on investment. Office of the Third Sector, Cabinet Office.

- Normann, R., & Ramirez, R. (1993). From value chain to value constellation. Harvard Business Review, 71(4), 65–77.

- Oderanti, F. O., & Li, F. (2016). A holistic review and framework for sustainable business models for assisted living technologies and services. International Journal of Healthcare Technology and Management, 15(4), 273–307. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1504/IJHTM.2016.084128

- Osborne, S. P., Radnor, Z., & Strokosch, K. (2016). Co-production and the co-creation of value in public services: a suitable case for treatment? Public Management Review, 18(5), 639–653. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2015.1111927

- Osterwalder, A., & Pigneur, Y. (2011). Aligning profit and purpose through business model innovation. In G. Palazzo, & M. Wentland (Eds.), Responsible management practices for the 21st century (pp. 61–75). Pearson International.

- Osterwalder, A., Pigneur, Y., & Tucci, C. L. (2005). Clarifying business models: origins, present, and future of the concept. Communications of the Association for Information Systems, 16(1), 1. DOI: https://doi.org/10.17705/1CAIS.01601

- Phillips, D., & Simpson, P. (2017). National standards, local risks: the geography of local authority funded social care, 2009–10 to 2015–16. Institute for Fiscal Studies.

- Porter, M. E., & Lee, T. H. (2013). The strategy that will fix healthcare. Harvard Business Review, 91, 10.

- Public Policy Projects. (2020). Connecting services, transforming lives. Public Policy Projects.

- Radnor, Z., Osborne, S. P., Kinder, T., & Mutton, J. (2014). Operationalizing co-production in public services delivery: the contribution of service blueprinting. Public Management Review, 16(3), 402–423. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2013.848923

- Rodrigues, R., & Glendinning, C. (2015). Choice, competition and care–developments in English social care and the impacts on providers and older users of home care services. Social Policy & Administration, 49(5), 649–664. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/spol.12099

- Schwamm, L. H. (2014). Telehealth: seven strategies to successfully implement disruptive technology and transform health care. Health Affairs, 33(2), 200–206. doi: https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2013.1021

- Shafer, S. M., Smith, H. J., & Linder, J. C. (2005). The power of business models. Business Horizons, 48(3), 199–207. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2004.10.014

- Shah, T., Wilson, L., Booth, N., Butters, O., McDonald, J., Common, K., … Murtagh, M. (2019). Information-sharing in health and social care: lessons from a socio-technical initiative. Public Money & Management, 39(5), 359–363. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/09540962.2019.1583891

- Stake, R. E. (1995). The art of case study research. Sage.

- Sugarhood, P., Wherton, J., Procter, R., Hinder, S., & Greenhalgh, T. (2014). Technology as system innovation: a key informant interview study of the application of the diffusion of innovation model to telecare. Disability and Rehabilitation: Assistive Technology, 9(1), 79–87. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3109/17483107.2013.823573

- Talbot, C. (2011). Paradoxes and prospects of ‘public value’. Public Money & Management, 31(1), 27–34. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/09540962.2011.545544

- Teece, D. J. (2010). Business models, business strategy and innovation. Long Range Planning, 43(2), 172–194. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2009.07.003

- Telecare Services Association. (2017). A digital future for technology enabled care? Retrieved from: https://www.tsa-voice.org.uk.

- Tewdwr-Jones, M., Goddard, J., & Cowie, P. (2015). Newcastle City futures 2065: anchoring universities in urban regions through city foresight. Newcastle Institute for Social Renewal, Newcastle University.

- Triantafillou, P. (2020). Accounting for value-based management of healthcare services: challenging neoliberal government from within? Public Money & Management, 1–10. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/09540962.2020.1748878

- Turner, K., & McGee-Lennon, M. (2013). Advances in telecare over the past 10 years. Smart Homecare Technology and TeleHealth. Retrieved from: www.dovepress.com.

- Vargo, S. L., & Lusch, R. F. (2004). Evolving to a new dominant logic for marketing. Journal of Marketing, 68(1), 1–17. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.68.1.1.24036

- Vargo, S. L., & Lusch, R. F. (2008). Service-dominant logic: continuing the evolution. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 36(1), 1–10. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-007-0069-6

- Wainwright, D.W., Oates, B.J., Edwards, H.M., & Childs, S. (2018). Evidence-based information systems: a new perspective and a road map for research-informed practice. Journal of the Association for Information Systems, 19(11), Article 4. DOI: https://doi.org/10.17705/1jais.00519

- Walsham, G. (2006). Doing interpretive research. European Journal of Information Systems, 15(3), 320–330. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.ejis.3000589

- Waring, T., & Wainwright, D. (2015). Integrating health and social care systems in England—a case of better care? Paper presented at the Annual Irish Academy of Management Conference, September 2015.

- Wenzl, M., Naci, H., & Mossialos, E. (2017). Health policy in times of austerity—a conceptual framework for evaluating effects of policy on efficiency and equity illustrated with examples from Europe since 2008. Health Policy, 121(9), 947–954. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2017.07.005

- Wherton, J., Sugarhood, P., Procter, R., Hinder, S., & Greenhalgh, T. (2015). Co-production in practice: how people with assisted living needs can help design and evolve technologies and services. Implementation Science, 10(1), 1. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-015-0271-8

- Wildavsky, A. (1977). Doing better and feeling worse: the political pathology of health policy. Daedalus, 105–123. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-349-04955-4_13

- Wright, G. H., & Taylor, A. (2005). Strategic partnerships and relationship marketing in healthcare. Public Management Review, 7(2), 203–224. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/14719030500091251

- Yunus, M., Moingeon, B., & Lehmann-Ortega, L. (2010). Building social business models: lessons from the Grameen experience. Long Range Planning, 43(2), 308–325. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2009.12.005

- Zott, C., & Amit, R. (2010). Business model design: an activity system perspective. Long Range Planning, 43(2), 216–226. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2009.07.004

- Zott, C., Amit, R., & Massa, L. (2011). The business model: recent developments and future research. Journal of Management, 37(4), 1019–1042. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206311406265