IMPACT

Using an archival study of financial statements prepared in accordance with International Public Sector Accounting Standards (IPSAS), this article reports on inconsistent practices and the lack of explanation of the differences between budget execution and accrual accounting. If the recommendations in this article are followed, public sector financial statements will be more accessible and comparable, adding to the credibility of public sector financial reporting.

ABSTRACT

Budget execution statements and accrual accounting financial statements are complementary but report different revenues, expenses, and surplus amounts. To make these differences understandable, IPSAS requires a reconciliation of the actual amounts in the budget execution statement with the financial performance or cash flow statements. This article analyses financial statements and demonstrates that entities approach this reconciliation differently, making a comparison challenging. This article recommends that more extensive guidance should be issued to improve comparability.

Introduction

Presentation of budget information in financial statements is a feature of public sector reporting. A public sector budget is a parliamentary mandate and a report to the public at large. Thus, budget plays an essential role in governance. Parliaments around the world pay more attention to budgets than to financial statements. Budget systems were in place long before financial statements were introduced in the public sector. The International Public Sector Accounting Standards Board (IPSASB), the international standard-setting body for public sector financial reporting, issued IPSAS 24 Presentation of Budget Information in Financial Statements in 2006 for entities that prepare their financial statements in accordance with IPSAS and make their budget publicly available. IPSASB requires these entities to include certain budget information in the financial statements. IPSASB does not impose any obligations on entities regarding the preparation of budgets because budgeting is considered to be outside IPSASB’s mandate.

The United Nations (UN) and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) issue standards on certain aspects of budgeting, such as budget classification, but not on the budgetary basis (cash basis, accrual basis, commitment basis or the hybrid basis). The International Budget Partnership’s Open Budget Initiative is a global research and advocacy programme that supports the adoption of transparent, accountable, and participatory public finance systems but does not issue standards relating to the budgetary basis. Jurisdictions choose their own budgeting practices and there is no noticeable tendency of convergence. Most public sector organizations prepare their budget on a cash basis with some modifications, but some public sector organizations, such as government institutions in Australia and New Zealand, present a complete set of projected financial statements that include a cash flow statement, a statement of financial performance, a statement of financial position and related notes. In this article, the actual amounts in comparison with the budgeted amounts are referred to as ‘budget actuals’. Budget actuals are prepared on a comparable basis with the budget.

There is an ongoing debate among academics, practitioners, and standard-setters as to whether budgeting and accounting should apply the same basis. One school of thought teaches the merits of consistency (in both budgeting and accounting on an accrual basis), while another maintains the position that budgeting should continue to be on a (near) cash basis even if the accrual basis is introduced to accounting and that a reconciliation should explain the differences. Although a small number of countries apply the full accrual basis for both budgeting and accounting, most countries combine accrual accounting with cash budgeting (OECD/IFAC, Citation2017). Reconciliation is needed for this large group of countries to allow the users of financial statements, academics, practitioners, and standard-setters to understand and compare the differences between budgeting and accounting between entities and over time.

Accounting standards that require budget information to be included in the financial statements usually require a reconciliation of the actual amounts in the comparison of budget and actual amounts (management accounting) on the one hand, and the statement of financial performance or the cash flow statement (financial accounting) on the other, if they are not prepared on the same basis. IPSASB and several national public sector accounting standard-setters, such as the United States Federal Accounting Standards Advisory Board (FASAB, Citation1997, Citation2017) and the Minister of Public Action and Accounts in France (CNOCP, Citation2016), issue such guidance.

The main objective of the reconciliation is to explain how the information on the use of budgetary resources relates to the accrual information in the statement of financial performance and the cash information in the cash flow statement. Without a reconciliation, the reasons why budgetary revenues and expenditures are different from accrual revenues and expenses, as well as the cash receipts and payments, may be unclear to users of the financial statements. The reconciliation also serves as a useful control on the consistency between the budget actuals and the statement of financial performance or the cash flow statement. Reconciling these differences adds to the understandability and credibility of financial statements.

This article explores the accrual basis accounting financial statements of international organizations and analyses the reconciliations of budget execution and financial performance or cash flows from the perspective of comparability. Comparability is one of the qualitative characteristics of financial information in IPSASB’s Conceptual Framework for General Purpose Financial Reporting by Public Sector Entities (IPSASB, Citation2014). Comparability enables users to identify and understand similarities and differences. Information regarding a reporting entity is more useful if it can be meaningfully compared with similar information from other entities, or the same entity in a different period or date. Comparability improves the usefulness of financial statements facilitating trend analyses (comparing periods) and cross-sectional analyses (comparing public sector entities). Information presented in a comparable manner is readily understandable and comparable for the users of financial statements.

This article reports on a study that addressed the research question:

Does the reconciliation requirement in IPSAS 24 lead to reconciliations of budgeting and accounting that are comparable between IPSAS 24 adopters?

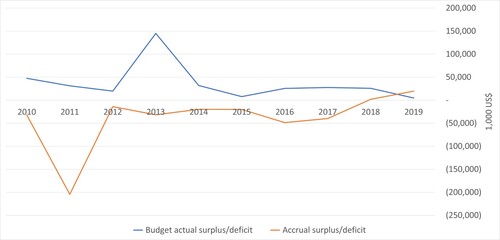

Differences between budget execution and financial performance or cash flows are often material, necessitating both a reconciliation and an explanation. For example, UNESCO reported an accrual accounting surplus of US$1.8 million and a budget surplus of US$25.8 million in 2018.

Literature review

Existing literature demonstrates that, although there is no consensus in the literature regarding whether both budgeting and accounting should follow the accrual basis, all authors agree that, if budgeting and accounting bases differ, a reconciliation of the two should be provided.

One stream of literature advocates consistency between budgeting and accounting. According to the IMF (Citation2012): ‘International standard-setting bodies (such as the UN, IMF, Eurostat, and IPSASB) should work to harmonize reporting standards for budgets, statistics, and accounts’. According to Warren (Citation2015):

In Canada, budgets have conventionally been prepared on the same basis as the financials ever since standards were developed in the 1980s. In Canada, the argument that there is no proper accountability if different bases are used and that the so-called ‘reconciliations’ do not really work has been readily accepted.

In its comment letter, the New Zealand Financial Reporting Standards Board (Citation2006) emphasized:

… in order to achieve full accountability and to provide understandable information to users, the accounting and the budgetary basis need to be the same. We recognize that change in this area is difficult given the different administrative arrangements existing in different jurisdictions. However, we believe that it would be appropriate for the IPSASB to publicly encourage public sector entities to prepare budgets and financial statements on the accrual basis in order to enhance accountability.

Several countries, including Australia, the United Kingdom, and Switzerland, have implemented both accrual accounting and budgeting. Blöndal (Citation2003, Citation2004) discussed key issues and developments in accrual accounting and budgeting. Arguing in favour of integrating budgeting and accounting and eliminating the need for reconciliation, Cortes (Citation2006) noted:

The adoption of accrual accounting in itself is not sufficient to ensure that the reforms that have been introduced are successful in achieving their goals, and it should also be introduced to the budgetary system because inevitably both are complementary. In decision-making, the government needs a clear idea what effects policies will have on its financial situation, and this is only possible if a similar basis is used for budgeting purposes and financial reporting.

There is unanimous support in the literature for the requirement to present a reconciliation of budgeting and accounting if the budget and financial statements are prepared on different bases. The IMF (Citation2012) promotes the ‘alignment of reporting standards used in budgets, statistics, and accounts with any remaining discrepancies set out in reconciliation tables’. Reichard and Van Helden (Citation2016) stated: ‘Evidently, reconciliation adaptations are needed at the end of the year for comparing the end-of-year budget execution report with the income statement’. Dabbicco and Mattei (Citation2020) also added, ‘Any differences between the different types of financial data should be transparently reconciled for users and stakeholders’. Acknowledging the need for a reconciliation of budgeting and accounting, Anessi-Pessina and Steccolini (Citation2007) conducted a longitudinal study of Italian municipalities and found that ‘in a system based on the coexistence between (cash- or commitment-based) budgetary accounting and accruals reporting, as experience with the use of accruals accounting increases, the reconciliation between accrual- and budgetary-based results becomes more difficult, and the “errors” of reconciliation increase’. They also found that ‘over time, the situation has not significantly improved. Rather, ‘experience’ seems to have increased the irreconcilability between budgetary and accrual accounting’. According to Anessi-Pessina and Steccolini, these findings ‘cannot obviously be generalized beyond the experience analysed, but can provide a useful starting point for further investigation in other countries and levels of government, and further studies should investigate the differences between budgetary and accruals results’. The literature review demonstrates that there is a shared belief that there is a need for a reconciliation of budgeting and accounting, although some authors consider this as second best to a budget and financial statements prepared on the same bases because the latter eliminates the need for reconciliation.

Most of the literature focuses on national and subnational governments, so this study was on the practical implementation of the reconciliation requirements for intergovernmental organizations. Research regarding financial reporting by intergovernmental organizations is scant; a few examples are works by Bergmann (Citation2010), Bergmann and Fuchs (Citation2017), and Mattei et al. (Citation2020), who analysed various factors that affect the comparability of IPSAS financial statements of international organizations.

While this article analyses the reconciliation of budgeting and accounting, other studies have analysed the reconciliation of accounting and statistics (national accounts): for example Jones (Citation2003), Caruana (Citation2016), Dabbicco (Citation2013, Citation2018), Giosi et al. (Citation2015), Jesus and Jorge (Citation2015), Jorge et al. (Citation2014, Citation2016, Citation2018), and Dasí et al. (Citation2016). These reconciliations present the adjustments made by statisticians on source data from public accounting systems to arrive at harmonized statistical measures.

The literature review also revealed that little attention has been paid to the design and comparability of the reconciliation of budgeting and accounting. This article aims to fill this gap in the literature.

Research method and composition of the sample

The research methodology employed in this article was a review and analysis of IPSAS financial statements prepared by 45 intergovernmental (also referred to as international or supranational) organizations. The 45 intergovernmental organizations are CERN, EU, EUIPO, Europol, FAO, IAEA, ICAO, ICC, ILO, IMO, Inter-Parliamentary Union, IOM, IRENA, ITC, ITER, ITU, NATO ACO, OPCW, OSCE, PAHO, UN, UNAIDS, UNCDF, UNDP, UNEP, UNESCO, UNFPA, UN-Habitat, UNHCR, UNICEF, UNIDO, UN International Residual Mechanism for Criminal Tribunals, UNITAR, UNJSPF, UNODC, UNOPS, UNRWA, UNU, UN Women, UNWTO, UPU, WFP, WHO, WIPO, and WMO. The entities were selected based on public availability of accrual-based financial statements: there were 43 in total (96%) for the year 2019, one (2%) in 2018 and 1 in 2017. To keep the dataset homogeneous, national or subnational governments were not included.

Out of the 45 organizations in the study, 42 (93%) notes to the financial statements claim compliance with IPSAS and three (7%) (the EU, EUIPO, and Europol), with ‘accounting rules that are based on IPSAS’. Since 2018, the Commissioner for Budget of the European Commission in the foreword to the financial statements has asserted that ‘The consolidated annual accounts of the European Union are produced in accordance with IPSAS’. According to the audit opinions, all financial statements present a true and fair view, 43 of them (96%) unqualified and two of them (4%) with qualifications unrelated to the budget information in the financial statements. The audit opinions of 39 (87%) financial statements were issued by a court of audit or auditor general of a member state, five (11%) by an international public sector auditor, such as the International Board of Auditors for NATO (IBAN) or the European Court of Audit (ECA), and one (2%) by a private sector audit firm.

Critical issues regarding the presentation of budget information in financial statements were addressed, highlighting the current lack of comparability between entities. The critical issues analysed related to the reconciliation of budgeting and accounting. Evidence collected from an overall initial assessment of the financial statements showed material issues relating to the following: the amounts being reconciled (budget revenues, expenses, or surplus/deficit versus accrual amounts, or cash flows); and the reconciling items. Considering their impact on the design of the reconciliation, the requirements in IPSAS 24 related to these matters are explained next in this article. These issues are then analysed and examples given of inconsistencies and comparability problems in the financial statements: are the weaknesses in terms of comparability brought about by options allowed by IPSAS 24’s lack of clarity regarding the standard, or by a lack of compliance with the standard? This article serves as a kind of a post-implementation review of the reconciliation requirements in IPSAS 24, which was issued in December 2006.

Reconciliation within the context of IPSAS 24 requirements

The reconciliation of budgeting and accounting, the primary focus of this article, should be examined within the broad context of the presentation of budget information in financial statements as required by IPSAS 24.

Comparison of budget and actual amounts

The first requirement in IPSAS 24 (paragraphs 14, 21, and 31) is that IPSAS financial statements should include a comparison of the original budget and the revised budget with actual amounts (budget actuals). This comparison must be made according to the same accounting basis applied in preparing the budget (for example cash basis, accrual basis, commitment basis, or any other basis), classification basis (for example economic, functional, or programme classification of expenses), entities (for example central government), and period (for example calendar year).

IPSAS 24 offers two alternatives for disclosing the comparison between the actual amounts and the budget, which are either a separate statement (‘statement of comparison between budget and actual amounts’) or an additional column in the financial statements. The latter is only allowed if the budget and financial statements have been prepared on a comparable basis.

Explanation of the differences between budget and actual amounts

The second requirement in IPSAS 24 (paragraph 14.c) states that the entity must explain the material differences between the budget and the actual amounts on a comparable basis. Such disclosure may either be included in the financial statements or in another document that is presented with the financial statements if the notes to the financial statements refer to that document.

Explanation of the differences between original and final budgets

The third requirement in IPSAS 24 (paragraph 29) is that the entity must explain the differences between the original and final budgets and must state whether they are due to reclassifications within the budget (virements) or other factors. Without this requirement, the value of the required comparison of budget and actual amounts can be limited if the entity has revised the budget by the end of the budget year to align it with the estimates of the actual amounts.

Disclosure of budgetary basis, classification basis, period, and scope

The fourth requirement in IPSAS 24 relates to various budget-related disclosures, such as budgetary basis (paragraph 39), classification basis (paragraph 39), period (paragraph 43), and the entities included in the budget (paragraph 45). Budgetary basis refers to the accrual, cash, or other bases of accounting adopted in the budget that has been approved by the legislative body (IPSAS 24, paragraph 7). A classification basis might be described, for example, as ‘an economic classification in accordance with GFSM 2014’ or ‘a functional classification in accordance with the Classification of Functions of Government (COFOG)’ (IMF, Citation2014).

Reconciliation of budget actuals and actual amounts in the financial statements

The fifth requirement only applies to entities that do not prepare their financial statements and budget on a comparable basis. They must include in the financial statements a ‘Reconciliation of actual amounts on a comparable basis and actual amounts in the financial statements’. summarizes the reconciliation requirements in IPSAS 24, paragraph 47.

Table 1. Reconciliation requirements in IPSAS 24, paragraph 47.

If the accrual basis is adopted for the budget, IPSAS 24 requires that the budget actuals should be reconciled to the total revenues and expenses but does not require budget actuals to be reconciled to accrual surplus/deficit. This does not comply with IPSAS 1 Presentation of Financial Statements that does not require presenting total expenses. By contrast, IPSAS 24 requires that budget actuals should be reconciled to net cash flows but not with total receipts and payments, which is consistent with IPSAS 1 and 2 that do not require presenting total receipts and payments. The cash basis IPSAS (IPSASB, Citation2017) requires that budget actuals are reconciled to total receipts and payments.

The objective of the reconciliation is, in the words of IPSASB, to ‘enable the entity to better discharge its accountability obligations, by identifying major sources of difference between the actual amounts on a budget basis and the amounts recognized in the financial statements’ (IPSAS 24, paragraph 49) and ‘to enable users to identify the relationship between the budget and the financial statements’ (IPSAS 24, paragraph BC 17).

Reconciliation: issues and challenges in practical implementation

This section examines the issues and challenges of applying the requirements presented in IPSAS 24 to prepare a reconciliation of budgeting and accounting. By describing the widely divergent practices in presenting reconciliations of budgeting and accounting, this section demonstrates the existing lack of comparability between entities. This section also assesses whether the practices described comply with the standard.

Reconciliations will rarely be fully consistent across entities because they serve as a bridge between financial statements, which follow standards, and budgets, which do not. The differences between budgeting and accounting are unavoidable because their underlying logic is not the same. This section analyses how reconciliation should be designed to bring out the differences between budgeting and accounting in a comparable manner. In practice, a comparable basis rarely happens because budgeting practices were established long before IPSASs were developed and budgeting practices have not been affected by IPSAS implementation.

Reconciling budget actuals: with accrual amounts or with cash flows

IPSAS requires entities to reconcile the ‘actual amounts presented on a comparable basis to the budget’ to net cash flows, and if the budget is prepared on an accrual basis, total revenues, and expenses, but it does not clarify which ‘actual amounts presented on a comparable basis to the budget’ should be reconciled. Accommodating a variety of budget formats, the standard merely refers to ‘the major totals presented in the statement of budget and actual comparison’ (paragraph 51) and states that ‘this standard does not preclude reconciliation of each major total and subtotal, or each class of items, presented in a comparison of budget and actual amounts with the equivalent amounts in the financial statements’ (paragraph 49).

The interpretation of ‘actual amounts presented on a comparable basis to the budget’ varied among the financial statements reviewed, and these amounts were either budget expenditure only or budget revenues, budget expenditure, and budget surplus/deficit. Entities that use the term ‘expenditure’ in IPSAS financial statements should clarify its meaning because expenditure is not a generally accepted accounting terminology and the IPSAS standards do not define it. GFSM 2014 (IMF, Citation2014) includes a definition for statistical purposes: ‘Expenditure is the sum of expense and the net investment in nonfinancial assets’.

All financial statements analysed presented a reconciliation of budgeting and accounting. provides an overview of the reconciliations prepared by international organizations. Out of the 45 international organizations analysed, 10 prepare two different reconciliations, and three prepare a reconciliation that does not fit in any of the classifications (see ). A total of 52 reconciliations were analysed. Some of them present a reconciliation of budget actuals and cash flows in accordance with the standard, others present a reconciliation of budget actuals and revenues and expenses, and some present both. Some of the financial statements analysed do not present a reconciliation of budget actuals and cash flows as required by the standard but, instead, present a reconciliation of budget actuals and revenues and expenses.

Table 2. Reconciliations (N = 52) of budget actuals and accrual or cash information of IPSAS financial statements of international organizations.

Most financial statements start the reconciliation with the budget actuals (top line) and end with the revenues and expenses in the statement of financial performance (bottom line), but some organizations do this the other way around (for example UNESCO), which is a deviation from the IPSAS requirement that ‘the actual amounts presented on a comparable basis to the budget … are reconciled to the actual amounts presented in the financial statements’. To make reconciliations more comparable, all entities need to comply with the standard and present the budget actuals as the top line of the reconciliation. When reconciling with cash flows, all organizations should present budget actuals as the top line and net cash flows as the bottom line.

Out of the 52 reconciliations analysed, 27 (52%) present only expenditure in their budget and no revenues (the budget expenditure column in ), whereas 25 (48%) present a surplus/deficit in their budget (the budget surplus/deficit column in ). This discrepancy is inherent in the budget preparation, causing an unavoidable lack of comparability of the reconciliations. A reconciliation of budget expenditure and expenses is prepared by eight international organizations (15%). These entities do not reconcile budget actuals with revenues as required by IPSAS 24, paragraph 47(a).

A reconciliation of budget expenditure and accrual surplus/deficit is prepared by one international organization (2%), UPU. In this case, revenues on an accrual basis are one of the reconciling items (presentation difference). UPU prepares a reconciliation of budget expenditure and expenses, as required by IPSAS, and then extends the reconciliation to the accrual surplus/deficit, which is more informative than required by IPSAS.

A reconciliation of budget expenditure and net cash flows from operating, investing, and financing activities is prepared by 18 international organizations (35%). Arguably, this practice complies with IPSAS 24, paragraph 47, which refers to ‘actual amounts presented on a comparable basis to the budget’, but does not specify which amounts. In this case, receipts on a cash basis are one of the reconciling items. The UN, for example, present revenues, expenditure, and ‘net total’ (budget surplus/deficit) in the statement of comparison of budget and actual amounts but only reconcile the expenditure with the net cash flows from operating, investing, and financing activities.

A reconciliation of budget surplus/deficit and accrual surplus/deficit is prepared by 15 international organizations (29%). Reconciling with accrual surplus/deficit is an informative practice that goes beyond IPSAS 24, which requires reconciling with total revenues and total expenses, not surplus/deficit. An example is the EU, which presents a reconciliation of budget surplus/deficit and accrual surplus/deficit but not, as required by IPSAS, a reconciliation with net cash flows. Another example is UNESCO (see ), which provides a reconciliation that includes a breakdown of entity differences by entities and a breakdown of basis differences by revenues and expenses. These breakdowns are informative but not explicitly required by the standard.

Table 3. UNESCO’s reconciliation of budget actuals and accrual surplus/deficit 2018.

A reconciliation of budget surplus/deficit and net cash flows from operating, investing, and financing activities is prepared by 10 international organizations (19%). Reconciling budget amounts with net cash flows is required for all entities, even for those that prepare budgets on an accrual basis. One example is UNESCO (see ). Another example is ILO, which presents three comparisons of budget and actual amounts (for three budgetary entities) and reconciles the total surplus on a budgetary basis with the net cash flows.

Table 4. UNESCO’s reconciliation of budget actuals and net cash flows 2018.

Ten international organizations prepare two reconciliations of the budget actuals: one with the amounts in the statement of financial performance and the other with the amounts in the cash flow statement. Preparing both reconciliations is a requirement for entities applying the accrual basis for budget preparation. As none of these 10 organizations apply the accrual basis for budget preparation, the reconciliation with the amounts in the statement of financial performance is a disclosure that goes beyond the requirements in the standard.

Differences: the reconciling items

According to IPSAS, budget actuals should be reconciled to the actual amounts presented in the financial statements, identifying any basis, timing, and entity differences separately. This does not preclude any other differences that are identified, and many organizations identify presentation differences. Most organizations interpret this to mean that presenting only the total amounts of the basis, timing, entity, and presentation differences is sufficient, but some entities provide a breakdown of each of these differences. IPSASB can improve the comparability of reconciliations between entities by clarifying whether breakdowns are required or not.

The EU (Citation2008) reconciles budgeting and accounting by ‘identifying separately the major differences on both the revenues and the expenditure side’ and not by basis, timing, and entity differences as required by the standard. According to the EU (Citation2019), the reconciliation of the budget actuals and the accrual amounts in the financial statements serves as a ‘useful consistency check’. This consistency check is only effective if the reporting entity does not use a balancing item (also known as a ‘plug’) when preparing the reconciliation. The use of inconsistent data recording systems in preparing the budget actuals and the amounts in the statements of financial performance and cash flows may lead to reconciliation problems, but unexplainable differences should be allocated to the other reconciliation line items. To be reliable, no balancing item should be included in any reconciliation.

Basis differences: Regarding basis differences, IPSAS 24, paragraph 48(a) states that these ‘occur when the approved budget is prepared on a basis other than the accounting basis’. The budgetary basis, the basis of accounting adopted in the budget and the budget execution statement, is often not well explained in financial statements, thus limiting the understandability of the budget and the reconciliation of budget actuals with the statement of financial performance or the cash flow statement. Preparing financial statements on accrual accounting and budgets on a cash or commitment basis is quite common in the public sector. This usually involves entities that previously prepared both budget and financial statements on cash or commitment bases and implemented accrual accounting for the financial statements only.

Several UN organizations (for example the WFP) describe their budgetary basis as the ‘commitment basis’, implying that expenditure, and an obligation, is recognized when the entity enters a commitment. Budget commitments are not recognized in IPSAS financial statements. The EU applies the accrual basis for its financial statements and uses a mixed cash and commitment basis for the budget. Many UN organizations also do this, with some exceptions that state that they apply a modified accrual basis for budget preparation, such as ILO, IMO, UNOPS, UNWTO, UPU, and WIPO. Many UN organizations describe their budgetary basis as either a ‘modified cash basis’ or a ‘modified accrual basis’. Some organizations (for example UNCDF, UNEP, UNITAR, and UNDP) that used to label their budgetary basis as ‘modified accrual’, now label that same budgetary basis as ‘modified cash’. Because there is no generally accepted accounting definition of these modified concepts and the IPSAS standards do not include a definition, users of financial statements need a specific description of the modifications from the cash or accrual basis that the entity applies. Many financial statements of international organizations include a nebulous description of the budgetary basis such as ‘modified cash basis’ without disclosing the modifications applied, which does not meet the qualitative characteristic of understandability and comparability as required by IPSAS. These examples demonstrate that basis differences are not presented consistently, thereby limiting the comparability of IPSAS financial statements.

Timing differences: Regarding timing differences, IPSAS 24, paragraph 48(b) states that they ‘occur when the budget period differs from the reporting period reflected in the financial statements’, but no clarity or further explanation of timing differences is provided in the standard. This has led to diverging interpretations, particularly when budgets are prepared on a biennial basis.

Many UN organizations prepare biennial budgets (for a two-year period) without separating the amounts for the two periods, whereas IPSAS stipulates that financial statements must be prepared at least once a year. Out of the 37 UN organizations in the dataset, 28 (76%) prepare biennial budgets. Some UN organizations with biennial budgets report timing differences as one of the line items in the reconciliation (for example ILO), whereas many others do not. Timing differences are not presented consistently, thereby limiting the comparability of IPSAS financial statements.

Entity differences: Regarding entity differences, IPSAS 24, paragraph 48(c) states that they ‘occur when the budget omits programmes or entities that are part of the entity for which the financial statements are prepared’. Entity differences usually arise because the reporting entity of the consolidated financial statements has wider boundaries than the budget. A few international organizations (UN, ICC) report entities included in the budget but not in the consolidated financial statements, which does not seem to be consistent with the standard. UNOPS presents a comparison of budget and actual amounts for its management budget and projects separately. These examples demonstrate that entity differences are not presented consistently, thereby limiting the comparability of IPSAS financial statements.

Presentation differences: IPSAS does not explicitly require identifying presentation differences. IPSAS 24, paragraph 28 merely comments, ‘There may also be differences in formats and classification schemes adopted for presentation of financial statements and the budget’.

Many organizations report revenues as presentation differences because the budget only reflects expenditure. This is quite common in the UN. For example, UNRWA states, ‘Revenue that does not form part of the statement of comparison of budget and actual amounts is reflected as presentation differences’. Moreover, UNICEF states, ‘The actual budget does not include revenue. The difference pertaining to revenue is shown under “presentation differences” in the reconciliation of budget actuals and net cash flows’. These examples demonstrate that presentation differences are not presented consistently, thereby limiting the comparability of IPSAS financial statements.

Location: on the face of the statement or in the notes

IPSAS 24 allows presenting the reconciliation on either the face of or in the notes to the financial statements: ‘The reconciliation shall be disclosed on the face of the statement of comparison of budget and actual amounts, or in the notes to the financial statements’ (IPSAS 24, paragraph 47).

Out of the 45 entities investigated, only two (4%) present the reconciliation on the face of the statement of comparison of budget and actual amounts. These examples demonstrate that entities do not present the reconciliation of budgeting and accounting consistently. This inconsistency could be resolved by requiring all entities to present the reconciliation in the notes to the financial statements.

Illustrative examples of a reconciliation of budgeting and accounting

This section provides illustrative examples of reconciliations of budgeting and accounting that satisfy many of the qualitative characteristics of financial information while considering the pervasive constraints on information according to IPSASB’s conceptual framework. The qualitative characteristics of information are relevance, faithful representation, understandability, timeliness, comparability, and verifiability. Pervasive constraints on information are materiality, cost-benefit, and achievement of an appropriate balance between qualitative characteristics.

UNESCO is one of the intergovernmental organizations that prepare two reconciliations (UNESCO’s financial statements are available at https://unesdoc.unesco.org). UNESCO reconciliations are best-in-class examples because they provide sufficient specification of line items to understand the differences while avoiding information overload. presents its reconciliation of the actual amounts on a comparable basis in the comparison of budget and actual amounts with the accrual surplus/deficit. presents its reconciliation of the actual amounts on a comparable basis in the comparison of budget and actual amounts with the net cash flows from operating, investing, and financing activities. UNESCO provides the following explanation:

The principal adjustments impacting the reconciliation between the budget and the Statement of Financial Performance are as follows:

Capital expenditures capitalized and depreciated over useful life under accrual accounting (generally recorded as current year expenses in the budget);

Under the budget, assessed contributions to be received in Euros and the corresponding expenditure are translated into US dollars at the Constant Dollar Rate. In the financial statements assessed contributions received in Euros and their corresponding expenditure are translated into US dollars using the UN Operational Rate of Exchange prevailing at the date of the transaction;

Under accrual accounting, employee benefit liabilities are reported in the Statement of Financial Position, and movements in liabilities impact the Statement of Financial Performance;

For budgetary purposes UNESCO records ‘unliquidated obligations’. Unliquidated obligations include both budget commitments which have not yet given rise to the delivery of a service at the reporting date, and real accruals for goods and services received but not yet invoiced/settled. Budget commitments are not recorded in the financial statements whereas real accruals are recognized in accordance with IPSAS.

Conclusion and recommendations

This article shows that financial statements prepared in accordance with IPSAS include reconciliations of budget actuals and actual amounts that are different from each other in many aspects. Some entities reconcile budget actuals with cash flows; others reconcile them with revenues and expenses or with accrual surplus/deficit. Some entities include revenues and expenditure by line item, whereas other entities only include total revenues and expenditure as budget actuals in the reconciliation. Some entities provide only total basis, timing, and entity differences, whereas others provide an itemized breakdown. Some offset certain differences, whereas others do not. Some entities include the reconciliation on the face of the statement, whereas others include it in the notes. Various terms defined in IPSAS 24 are interpreted in different ways, such as timing and presentation differences.

The reconciliation requirement in IPSAS 24 does not lead to reconciliations of budgeting and accounting that are, in all material respects, comparable between public sector entities. Further, amendments are needed to bring out the differences between budgeting and accounting.

To achieve this comparability, IPSASB should issue more specific guidance. On the basis of this analysis, the following are some recommendations:

Require two reconciliations of budgeting and accounting. First, a reconciliation of the actual amounts on a comparable basis in the comparison of budget and actual amounts with the accrual surplus/deficit—if the comparison of budget and actual amounts presents only budget expenditure, revenues should be one of the reconciliation differences. Second, a reconciliation of the actual amounts on a comparable basis in the comparison of budget and actual amounts with both the accrual surplus/deficit and the net cash flows from operating, investing, and financing activities. If the comparison of budget and actual amounts presents only budget expenditure, receipts should be one of the reconciliation differences.

Clarify that material differences between budget actuals and actual amounts in the financial statements should be itemized and explained. Currently, IPSAS requires ‘identifying separately any basis, timing, and entity differences’, which is generally interpreted to mean that no further breakdown or explanation of these three differences is required.

Clarify that differences in reconciliation should not be offset against each other; IPSAS 1, paragraph 48 prohibits offsetting assets and liabilities as well as revenues and expenses, not reconciliation differences.

IPSASB should require the reconciliation of budgeting and accounting to be disclosed in the notes to the financial statements. IPSAS currently allows the reconciliation to be disclosed either on the face of the statement of comparison of budget and actual amounts or in the notes to the financial statements.

Clarify the meaning of timing differences.

Provide additional guidance on the disclosure requirement of the budgetary basis. Currently, entities tend to describe the budgetary basis in an opaque manner, such as on a modified cash or commitment/cash basis.

Comparability would also improve if entities preparing IPSAS financial statements more fully complied with IPSAS 24. The following are some recommendations for the preparers of IPSAS financial statements:

Prepare a reconciliation of budget figures with the net cash flows in all cases, even if a reconciliation of budget figures with the accrual amounts is also prepared.

Disclose the budgetary basis and provide a definition of terminology if no generally accepted accounting definition exists, such as providing clarity in terms of the meaning of ‘modified cash basis’ and ‘modified accrual basis’.

Report timing differences if a budget period differs from the reporting period.

To better understand the effects of user needs, further studies should empirically investigate how the differences in the design of the reconciliation of budgeting and accounting relate to financial statements users’ perceptions of relevance and understandability. For example, choosing between a reconciliation of the budget actuals with either the statement of financial performance or the cash flow statement can be analysed. There is also an opportunity for empirical research in the observation that many public sector entities report an actual budget surplus/deficit exceeding the accrual accounting surplus/deficit. This is particularly relevant because the budget surplus/deficit is widely considered to be the headline figure. This study of international organizations could also be replicated for other public sector organizations, such as national governments. An interesting extension of this research would be to analyse the practical application of the reconciliation requirements of budgeting and accounting in other financial reporting frameworks, such as FASAB (Citation1997, Citation2017), and apply lessons learned for the continuing development of IPSAS.

Based on the findings presented in this article, IPSASB should consider issuing more specific guidance to improve the comparability of reconciliations of budgeting and accounting.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

References

- Adam, B. (2018). Comparison of the perception of overt and covert options in IPSAS financial statements by intergovernmental organizations. Tékhne—Review of Applied Management Studies, 16(1), 28–39.

- Anessi-Pessina, E. & Steccolini, I. (2007). Effects of budgetary and accruals accounting coexistence: Evidence from Italian local governments. Financial Accountability & Management, 23(2), 113–131.

- Bellanca, S. (2014). Budgetary transparency in the European Union: The role of IPSAS. International Advances in Economic Research, 20(4), 455–457.

- Bergmann, A. (2010). Financial reporting of international organizations: Voluntary contributions are the main issue. Yearbook of Swiss Administrative Sciences, 1, 197–206.

- Bergmann, A. & Fuchs, S. (2017). Accounting standards for complex resources of international organizations. Global Policy, 8(5), 26–35.

- Blöndal, J. (2003). Accrual accounting and budgeting: Key issues and recent developments. OECD Journal on Budgeting, 3(1), 43–59.

- Blöndal, J. (2004). Issues in accrual budgeting. OECD Journal on Budgeting, 4(1), 103–119.

- Caruana, J. (2016). Shades of governmental financial reporting with a national accounting twist. Accounting Forum, 40(3), 153-165.

- CNOCP (Conseil de normalisation des comptes publics) (2016). Cadre conceptuel des comptes publics relevant de la comptabilité d’exercice.

- Cortes, J. L. (2006). The international situation vis-à-vis the adoption of accrual budgeting. Journal of Public Budgeting, Accounting & Financial Management, 18(1), 1–26.

- Dabbicco, G. (2013). The reconciliation of primary accounting data for government entities and balance according to statistical measures: The case of the European Excessive Deficit Procedure Table 2. OECD Journal on Budgeting, 2013(1), 31–59.

- Dabbicco, G. (2018). A comparison of debt measures in fiscal statistics and public sector financial statements. Public Money & Management, 38(7), 511–518. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540962.2018.1527543

- Dabbicco, G. & Mattei, G. (2020). The reconciliation of budgeting with financial reporting: A comparative study of Italy and the UK. Public Money & Management. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540962.2019.1708059

- Dasí, R., Montesinos, V. & Murgui, S. (2016), Government financial statistics and accounting in Europe: Is ESA 2010 improving convergence? Public Money & Management, 36(3), 165–172. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540962.2016.1133964

- EU (European Union) (2008). European Union accounting rule 16 presentation of budget information in annual accounts. https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/info/files/about_the_european_commission/eu_budget/eu-accounting-rule-16-presentation-of-budget-information_2008_en.pdf

- EU (European Union). (2019). Annual accounts of the European Union 2019.

- FASAB (United States Federal Accounting Standards Advisory Board) (1997). Statement of Federal Financial Accounting Concepts (SFFAC) No. 1—Objectives of federal financial reporting.

- FASAB (United States Federal Accounting Standards Advisory Board). (2017). Statement of Federal Financial Accounting Standards (SFFAS) 53, Budget and Accrual Reconciliation.

- Giosi, A., Brunelli, S. & Caiffa, M. (2015). Do accrual numbers really affect the financial market? An empirical analysis of ESA accounts across the EU. International Journal of Public Administration, 38(4), 297–310. https://doi.org/10.1080/01900692.2015.999591

- Heiling, J., & Chan, J. (2012). From servant to master? On the evolving relationship between accounting and budgeting in the public sector. In Bergmann, A. (Ed.), Yearbook of Swiss administrative sciences (pp. 23–38). Staatliche Budgetprognosen und Rechnungsrealität.

- IFAC Public Sector Committee (2004a). Research report budget reporting.

- IFAC Public Sector Committee (2004b). Minutes from the PSC meeting in July 2004.

- IMF (International Monetary Fund). (2012). Fiscal transparency, accountability, and risk. Available at http://www.imf.org/external/np/pp/eng/2012/080712.pdf

- IMF (International Monetary Fund) (2014). Government Finance Statistics Manual (GFSM) 2014.

- IPSASB (International Public Sector Accounting Standards Board). (2014). The conceptual framework for general purpose financial reporting by public sector entities.

- IPSASB (International Public Sector Accounting Standards Board). (2017). Financial reporting under the cash basis of accounting.

- Jesus, M., & Jorge, S. (2015). Accounting basis adjustments and deficit reliability: Evidence from southern European countries. Revista de Contabilidad—Spanish Accounting Review. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.rcsar.2015.01.004

- Jones, R. (2003). Measuring and reporting the nation’s finances: Statistics and accounting. Public Money & Management, 23(1), 21–28.

- Jorge, S., Jesus, M. & Laureano, R. (2014). Exploring determinant factors of differences between governmental accounting and national accounting budgetary balances in EU member-states. TRAS: Transylvanian Review of Administrative Sciences, 10(44), 34–54.

- Jorge, S., Jesus, M. & Laureano, R. (2016). Governmental accounting maturity towards IPSASs and the approximation to national accounts in the European Union. International Journal of Public Administration, 39(12), 976–988.

- Jorge, S., Jesus, M. & Laureano, R. (2018). Budgetary balances adjustments from governmental accounting to national accounts in EU countries: Can deficits be prone to management? Public Budgeting & Finance, 38(4), 97–116.

- Khan, A. (2013). Accrual budgeting: Opportunities and challenges. In: Cangiano, M., Curristine, T. & Lazare, M. (Eds.), Public Financial Management and its Emerging Achitecture, IMF.

- Mattei, G., Jorge, S. & Grandis, F. (2020). Comparability in IPSASs: Lessons to be learned for the European standards, Accounting in Europe, 17(2), 158–182.

- New Zealand Financial Reporting Standards Board (2006). Comment letter Exposure Draft 27 (17 March).

- OECD/IFAC (2017), Accrual practices and reform experiences in OECD countries. OECD Publishing. http://doi.org/10.1787/9789264270572-en

- Reichard, C. & Van Helden, J. (2016). Why cash-based budgeting still prevails in an era of accrual-based reporting in the public sector. Accounting, Finance & Governance Review, 23(1&2), 43–65.

- Warren, K. (2015). Time to look again at accrual budgeting. OECD Journal on Budgeting 3(14), 113–129.