IMPACT

Implementing methodical co-creation as a new norm or social innovation in disability services takes more than regulatory policy steering or just delegating the change leadership mandate to first-line managers (FLMs). First, motivating and empowering FLMs requires sensemaking that is grounded in asset-based and sense-of-coherence approaches that both recognize and disturb their situated service narrative. Facilitated collective dialogues that are based on deep listening and salutogenic approach may help promote change towards the co-creative service culture. Second, pathological narratives that weaken FLMs’ motivation and perceived abilities may be gradually transformed to instead empower them for change leadership.

ABSTRACT

The authors analysed an ongoing service culture change in a strategically selected case. They illustrate how sensemaking can help to engender cultural change and, specifically, what sensemaking formats, approaches and strategies can have a transformative impact on first-line managers’ narrative. The article contributes to the literature with insights on leadership through sensemaking and how public bodies can act as ‘intelligent organizations’ to enhance service co-creation. In addition, the authors show how an action researcher can complement a middle manager in change leadership.

Introduction

Since the 1970s, co-creation has increasingly gained interest as a new approach to public service reform aiming to democratize and generate bottom-up renewal. Some authors stress direct citizen participation and influence in service co-production (Pestoff, Citation2009; Ostrom, Citation1996), while others underline the interactive and dynamic service value created at the nexus of interaction (Osborne et al., Citation2016; Torfing et al., Citation2016). In this study, we use the concept of co-creation to highlight the shift involved in this new approach from a passive beneficiary to an active citizen with the resources and capabilities to influence service design, delivery and value creation (Osborne, Citation2018). When applied methodically, i.e. in iterative interactions often co-creation results in a variety of innovations—not least governance and social innovations (Sinclair et al., Citation2018; Murray et al., Citation2010).

If successfully implemented, methodical co-creation is not only expected to produce local service innovations but will also generate social innovation on a greater scale by transforming the roles and relationships between street-level professionals and recipients of services in addressing unmet social needs (Sinclair et al., Citation2018; Evers & Brandsen, Citation2016). In public disability services in particular, co-creation represents a paradigm shift towards a health centered and asset-based approach (Baron et al., Citation2019), treating vulnerable citizens as having such resources as experiences, skills, networks or the potential to develop the resources required in co-creating the value of the personalized social assistance services they are entitled to. Methodical co-creation gradually increases service recipients’ influence on service delivery and their daily lives, and ultimately, enhances their wellbeing as humans and citizens.

An important political tool to facilitate a co-creation culture may be to grant citizens as service recipients (hereafter referred to as ‘users’ or ‘end-users’) co-determination rights. Nevertheless, earlier research has noted that, even in favourable institutional environments, service culture transformation largely depends on situated perceptions and practices of street-level professionals (Pestoff, Citation2009; Batalden et al., Citation2015), such as service personnel and first-line managers (FLMs) directly responsible for service implementation. Their collective sensemaking about service ethics and roles may contribute to either co-creating or co-destroying service value (Osborne et al., Citation2016). Sensemaking thus needs guidance for which organizational managers are seldom trained. Collective sensemaking may be defined as ‘the process in which individuals exchange provisional understandings and try to agree on consensual interpretations and a course of action’ (Stigliani & Ravasi, Citation2012, p. 1232), and determines what people see and do.

This article analyses how particular change leaders may facilitate collective sensemaking, and how that may have a transformative effect on the dominant service culture and narrative—especially in contexts that lack shared professional ethics and are perceived as challenging. Based on the theory of leading change through sensemaking (Iveroth & Hallencreutz, Citation2016), this study focuses on how an action researcher in the role of assigned sensemaking facilitator may help to engender cultural change, and specifically, what sensemaking formats, approaches and strategies may have a transformative impact on FLMs’ motivation and readiness for leading change towards co-creation.

The study particularly contributes with insights regarding how an action researcher may complement a middle manager in change leadership and the impact of a more holistic approach to sensemaking strategies grounded in a salutogenic perspective on change (Antonovsky, Citation1996). This allows for closing some knowledge gaps in how public organizations may act as ‘intelligent organizations’ (Virtanen & Stenvall, Citation2014, p. 92) to enhance co-creation culture in public social services to pave the way for social as well as a variety of service innovations. The arguments are based on a real-time study of municipal disability services in Jönköping, Sweden, representing a case with favourable institutional conditions, yet facing many challenges at service level.

In what follows, we first introduce a theoretical framework on engendering change through facilitated collective sensemaking and then detail our strategically selected case exemplifying a pioneering organization committed to improving its relationships with citizens assisted by social services. This is followed by a methods section where we specify the action researcher's and our distinct roles in the study, and then the findings section presents some longitudinally traced changes in the local service narrative as an outcome of facilitated sensemaking and analyses the contextually innovative sensemaking strategies and approaches. We end with conclusions and study contributions.

Theoretical framework

Transforming service culture towards co-creation integrating professional and user perspectives and assets is a challenge even when public policies and regulations advocate such a change (Karlsson, Citation2019; Jönköpings kommun, Citation2016).

Research on public administration and collective sensemaking argues that service culture transformation requires changes in service ethics, identities and social relations (Batalden et al., Citation2015; Weick et al., Citation2005) but it often fails due to insufficient skills in change leadership (Iveroth & Hallencreutz, Citation2016; Lüscher & Lewis, Citation2008). This involves seeing professional ethics as the (shared) moral determinant of understanding the purpose of public service and of professional norms and behaviour, especially in relation to end-users. Such ethics cannot be enforced by law but are self-imposed, inspired by sensemaking (Bowman & West, Citation2015). Collective sensemaking is acknowledged as a key mechanism to effect meaning, re-negotiation and cultural change (Aasen & Amundsen, Citation2013).

Sensemaking works by identifying, communicating, accepting and processing ideas (Weick et al., Citation2005; Ahrenfelt, Citation2013) about what individuals in organizations are doing, or supposed to be doing (Weick et al., Citation2005), and by renegotiating major values (Aasen & Amundsen, Citation2013). It is not until a new shared meaning with new ethics, identities and relational patterns is established (Aasen & Amundsen, Citation2013) and perceived as meaningful and manageable, i.e. creating a sense-of-coherence in individuals’ service context (Antonovsky, Citation1996; Weick et al., Citation2005), that service changes or innovation will be possible (Fonseca, Citation2002). Sensemaking affects FLMs’ incitement for change by providing guidance, feedback and efforts to adjust operational rules (Ahrenfelt, Citation2013).

Scholars have argued that sensemaking dynamics might not necessarily bring alignment to the new organizational vision or policy expectations, contending that change is effected by complex responsive processes in individual contexts and should be seen as emergent (Aasen & Amundsen, Citation2013). When dispersed in multiple venues, communication and sensemaking become unpredictable and are unlikely to subdue to single managers’ efforts (Streatfield, Citation2001; Fonseca, Citation2002; Aasen & Amundsen, Citation2013). Nevertheless, research on future-oriented sensemaking maintains that it is possible to propel strategic change towards an intended normative vision through leaders or facilitators who act as ‘sensegivers’ (Gioia & Chittipeddi, Citation1991) and establish a symbiotic relationship with change recipients as ‘sensetakers’ (Huemer, Citation2012). Sensegiving here is seen as the process of attempting to influence ‘sensemaking and meaning construction of others towards a preferred redefinition of organizational reality’ (Gioia & Chittipeddi, Citation1991, p. 442), while sensetaking involves receiving and evaluating the sensemaking narratives of others (Huemer, Citation2012).

In organizational environments, senior or middle managers are usually seen as change leaders acting as sensegivers to influence individuals’ frames of reference (Iveroth & Hallencreutz, Citation2016; Lüscher & Lewis, Citation2008; Gioia & Chittipeddi, Citation1991). In a circular interpretation and communication process, sensegivers receive and provide meaningful interpretations and may help individuals to break habitual patterns and begin reframing narratives on ethics, identities and social relational patterns (Lüscher & Lewis, Citation2008) by provoking discussions and disrupting ingrained approaches. Nevertheless, sensegiving ambitions among leaders at the organizational top may not suffice (Gioia & Chittipeddi, Citation1991), especially when it comes to motivating and empowering street-level professionals, as they interact with citizens and have wide discretion over the dispensation of benefits or sanctions and are those ‘through whom citizens “experience directly the government they have implicitly constructed”’ (Lipsky, Citation1980, p. xi). Their situated experiences require specific sensemaking strategies and approaches to increase sense-of-coherence and ability to navigate in the landscape of change. Middle managers have the opportunity to affect the course of change among street-level professionals by listening, ‘tapping into’ and actively participating in dialogues and narration (Iveroth & Hallencreutz, Citation2016, p. 62) but usually lack appropriate training (Lüscher & Lewis, Citation2008). Here, action researchers may contribute as neutral but knowledgeable sensemaking facilitators, although their role and strategies in managerial sensemaking are under researched (ibid.).

Several sensemaking formats may be helpful, especially in smaller groups at the service level, to facilitate the hybrid change bearing the marks of strategically aimed and contextually emergent change at the same time (Iveroth & Hallencreutz, Citation2016) such as dialogues and narration. Dialogues offer a non-persuasive form of conversation that allows for uncovering and exploring different meanings about service ethics, identities and underlying social relational patterns (ibid.). A learning dialogue requires that individuals take responsibility for labelling their world and searching for useful knowledge (Bohm, Citation1996). Narration represents attempts to co-create a version of a contextualized reality—including who we are, what we do, and obstacles—and, when retained (Weick et al., Citation2005), has the power to shape individuals’ realities and actions (Iveroth & Hallencreutz, Citation2016; McBeth et al., Citation2014).

Change that requires altering individuals’ views and actions substantially (Lüscher & Lewis, Citation2008) may be facilitated through sensemaking. Independently of the interaction format, Iveroth and Hallencreutz (Citation2016, pp. 120–123) propose eight intertwined guidelines or strategies for leading change through sensemaking; in ‘order of magnitude’ these are: change through logic of attraction; provide a direction; translate; stay in motion; look closely and update; converse candidly; unblock improvisation; and facilitate learning.

Accordingly, such change may be enhanced by organizational leaders showing how to lead by example and directing individuals’ attention and analytical abilities towards clear goals commonly agreed on and translated to fit their realities; encouraging spontaneous action grounded in situational awareness; making people talk about their concerns; listening attentively by actively reflecting on the ‘truths’ of others; testing new ideas by deviating from routines by using available resources and skills; ensuring that individuals have necessary space for reflecting on new experiences; refraining from punishing failure but encouraging learning and feedback where necessary through training (ibid.).

The task of a change leader is to guide people through several organizational landscapes of meaning by carefully adopting combinations of the above sensemaking strategies. The sensemaking leader or facilitator has a major role in facilitating the shift from the dominant narratives and behavioural patterns or ‘the landscape of comfort’, to starting to question and dismantle these before entering ‘the landscape of inertia’, characterized by uncertainty, new routines and resistance, thus gradually advancing towards significant behavioural changes and learnings through trials in ‘the landscape of transformation’ (ibid., p. 118).

Since our study was based on processes in care services, we needed to complement the above strategies with a ‘salutogenic’ approach borrowed from the theory of health promotion by Antonovsky (Citation1996). This suggests that individuals—primarily end users but this can also be extended to service professionals—would accept and engage with change when it brings more sense-of-coherence (SOC) to new situations or when it becomes comprehensible in terms of information, control and opportunities to influence, possible to handle (clarifying access to needed resources) and meaningful (worthwhile investing resources in addressing the challenges). It also presupposes an asset-based approach to service professionals and users that acknowledges their everyday knowledge and skills in co-identifying problems and co-creating solutions (Jönköping kommun, Citation2018; Iveroth & Hallencreutz, Citation2016; Ahrenfelt, Citation2013).

Background

In Sweden, disability care services exemplify both a favourable and a challenging context for transforming public service culture towards co-creation. The Support and Service for Persons with Functional Impairments Act 1993 aims at boosting individuals’ with serious cognitive and physical disabilities self-determination prospects of living an independent life and exercise of citizenship. The Act grants such individuals a novel right to influence and ‘co-determine’ the design and implementation of the 10 authorized services they are entitled to, such as personal assistance (PA) (Socialstyrelsen, Citation2009; SFS, Citation1993, p. 387), which includes the right to influence personnel recruitment and the drafting and daily implementation of their PA plans.

Local municipalities both authorize and implement PA services (in competition with private providers). As service providers, they are mandated to organize personalized assistance for eligible individuals’ ‘basic’ needs, such as meals, personal hygiene, clothing and communication (SFS, Citation1993, p. 387). PA may also be considered for some ‘remaining’ needs (for example exercising, working, studying, making meals, structuring daily life, leisure time activities). Implementing this ambitious reform requires transforming service culture but this is challenged by lack of shared professional training and ethics emphasizing co-creation and, frequently, true organizational commitment (Karlsson, Citation2019).

Jönköping municipality in Sweden, with about 140,000 inhabitants and around 5000 employees in public social services, is a case of pioneering organizational commitment to service improvements and innovations. The ultimate goal is ‘a systemic way of working based on citizens’ needs’ (Jönköping kommun, Citation2016, p. 12) and citizens as active co-creators. Since 2012, the Jönköping’s social services department, upon request of its political board, has been implementing a new quality management system for social services called ‘DIALOGEN’ (Jönköping kommun, Citation2016), focusing on innovativeness, coherence and sustainability. The organization strives to find ways to support FLMs in leading their personnel towards meaningful citizen service improvements by shifting focus to end-user assets, influence and power balance in service relationships. This requires taking a systemic approach to change by addressing the cultural, management and support processes.

PA is one of the five areas of municipal disability care services where managers felt that their ‘current efforts towards [end-user] health promotion were insufficient’ and piloted an initiative to facilitate co-creation of service improvement by exploring a salutogenic approach. PA is led by an area manager and divided into units (17 at the time of the study), where each PA unit manager (FLM) is responsible for around five to 15 users with the help of teams of 25–50 employees (in total around 400 personal assistants).

Research methods

A disability service improvement pilot—a partner in an international service innovation project—was the case of our analysis. The pilot was introduced shortly after a major turnover among the FLMs, replacing about 70% of them in a short time, mainly because of perceived contextual challenges and new organizational aspirations. FLMs were confused as these circumstances disrupted the continuity in the service culture and weakened peer-to-peer support, jeopardizing service quality. By questioning the tradition of operating in small manager teams, FLMs now expressed a longing for more joined-up sensemaking. In terms of the landscape metaphor above, the organization was forced to leave ‘the landscape of comfort’ thereby opening opportunities for sensemaking processes about FLMs’ roles as change leaders and new relational patterns in ‘the landscape of inertia’ to facilitate the shift to co-creation culture in the ‘landscape of transformation’ (Iveroth & Hallencreutz, p. 118). During the pilot, senior management allocated time for learning dialogues and employed a consulting action researcher with professional background in social services to facilitate collective sensemaking. One aim was to explore the potential of the salutogenic or health promoting approach (Antonovsky, Citation1996) advocated by DIALOGEN to advance service co-creation and improvements.

We adopted an innovative research methodology in our study. Acting independently of the pilot, we explored the approach and strategies of the assigned action researcher in facilitating sensemaking. Our focus was on shared sensemaking activities that started in winter 2018 and continued until winter 2019. We evidenced the strategies and approach of the action researcher, assisted by the PA service area manager, in facilitating sensemaking and engendering service culture change (here understood as transformation of the dominant service narrative through ‘re-conceptualization’ of its major elements). ‘Re-conceptualization’ means challenging the established perceptions and information processing on individual and collective level (Ahrenfelt, Citation2013, p. 282).

To study the strategies employed over time, and their impact on transforming the service narrative, we conducted a real-time study acting as participant observers, with the consent of the area manager, the FLMs and the action researcher, based on guaranteed anonymity for FLMs and withdrawal rights. We followed the group for approximately two years, or as long as they found the assistance of an action researcher useful.

In their half-day dialogue sessions, the area manager, as a formal pilot leader, would introduce the pilot aims, the action researcher's role, comment on reflections and the next steps. The action researcher served as a key facilitator and led the bulk of the sensemaking dialogues, and study circles, including the assessment of service narrative transformation and service improvements. In the spirit of participatory action research (Adelman, Citation1993), the action researcher pursued emancipatory aims (Lüscher & Lewis, Citation2008) to empower the FLMs by transforming the disabling service narrative to enable them to do things differently.

In analysing action researcher strategies, we relied on a framework that synthesizes guidelines for leading change through sensemaking (Iveroth & Hallencreutz, Citation2016) and the salutogenic approach to change (Antonovsky, Citation1996). To move from ‘the landscape of comfort’ the action researcher used a variety of strategies including rigorous triangulation methods in collecting data that signalled service challenges and the need for changes (such as end-user focus groups, national surveys and recurring dialogues with FLMs), ensuring respectful dialogues and offering relevant theoretical approaches to guide change leadership. The action researcher engendered change by carefully switching between inquiry or sensetaking, sensebreaking or interrupting others’ understanding (Huemer, Citation2012) with empathy but from a critical perspective, and sensegiving or suggesting other reference frames to provide meaning, not least in reframing the narrative. The action researcher’s approach, strategies and impact on service narrative and culture are detailed in the findings section on sensemaking process.

To structure the shared patterns of meaning about co-creation and FLMs’ roles in facilitating it, and to explore their transformation over time, we relied on the method of narrative analysis. Narratives are powerful tools in reducing complexity and producing a locally plausible story as a source of guidance (Weick et al., Citation2005). Inspired by McBeth et al. (Citation2014) and Weick et al. (Citation2005), we structured the analysis of three recurring themes in FLM narration and dialogues around some typical narrative elements:

The ‘moral’ (McBeth et al., Citation2014) or service norms and ethics.

‘Settings’ (ibid.) and situated FLM capabilities.

‘Characters’ (ibid.) or, rather, ‘what is my role?’ and ‘how to respond to others?’ (Weick et al., Citation2005).These are called ‘identities’ and ‘relationships’ in this article.

We used a range of data collection techniques to secure validity, including document analysis of government policies and legislation, organizational reform policy, action researcher dialogue notes, nine participatory observations in FLM learning dialogue meetings and interviews. In total, 33 semi-structured interviews and conversations (see ) were conducted at early and late pilot stages with FLMs, area and senior managers in disability and social services, pedagogical tutors offering support to FLMs and their personnel groups and the action researcher.

Table 1. Interviews and conversations in the pilot study.

Six of the 17 volunteering FLMs with the longest PA service experience were interviewed at an early pilot stage in 2018 to explore the status quo of the services, their views of co-creation with users, FLMs’ roles as leaders in aiding co-creation and possible challenges to its realization in practice. The aim of the six follow-up interviews at a later pilot stage in 2020 was to disclose any major changes in FLMs’ mind-sets and practices, how they valued facilitated dialogues and how to sustain piloting improvements.

The participatory observations contributed rich information about the FLMs’ perspectives, the action researcher and management strategies employed to facilitate sensemaking and about their impact on reframing the collective narrative. The open dialogue atmosphere allowed us regular contact with FLMs’ narration of their service reality by exposure to a variety of their perceptions, moods, challenges, engagement, arguments and practical examples. A possible limitation was restricted access to a larger variety of platforms for sensemaking and individual interviews. Additionally, there was some personnel rotation in the manager group.

Findings: sensemaking content

This section details some of the content in FLMs’ sensemaking represented by three major and shared patterns of meaning by comparing their articulations at an early pilot stage: T1 (spring 2018), with those after the sensemaking dialogues at T2 (autumn 2019), as a way to clarify whether facilitated FLM dialogues and activities in the pilot context impacted on their perceptions and narration. In their sensemaking, FLMs had access to each other, to pedagogical tutors, to the area manager and the action researcher.

Norms: from user participation and influence to methodical co-creation

Study findings at T1 reveal that FLMs were in agreement about service normative aims to enhance end-user participation in social life, self-determination and empowerment by granting them some influence in their individual services. They were familiar with these norms and concepts from legislation and from the salutogenic approach that the senior management advocated as central to the social service culture, but were seen as difficult to systematically apply in practice.

Conversely, co-creation, as a term referring to service value co-creation with end-users, was relatively new to the FLMs. The term was not used in the regulations but had started to appear in the organizational language as way to interpret the legislative spirit. To most of the FLMs, co-creation sounded like a substitute for the norms of (formalized but limited) end-user participation and influence in social care. Yet, some FLMs interpreted co-creation as a qualitatively broader and deeper concept to imply ‘undertaking some of the [personal] assistance efforts together, enriching each other’s knowledge about it’, thus ‘shifting the focus away from professionals as experts to citizens, and accepting the ‘limitations and fluidness’ of their knowledge, so broadening the collective reference frame. They saw co-creation as a matter of pursuing a more open, adaptive approach towards end-users’ needs instead of deciding for them:

Co-creation may be about sitting down together with the user [to talk] about the implementation plan. The user articulates their needs when they can, and when they do not articulate those, it may also be a way to exert influence.

Co-creation is about being on the same level approximately … We and the user.

The user needs to exert some control over their daily life and even be asked [about services] on the level they can understand, and that gives them a sense of control and influence.

Co-creation is about doing things together, not only the specific service, but all that relates to it, such as how we contact and involve the user and those close by.

Co-creation for me is ultimately about things we do together with the engagement of all those concerned.

I think we often offer prompt but too simple solutions [to the users].

We need to learn how to communicate and question things without irritating the user.

At T2, almost a year and a half into the project, the FLM service improvement narrative had become more focused on co-creation impact as ‘the improvement for the citizen at the end’ and more consistent regarding the asset-based and learning approach as the basis for co-creation. Service users were seen as stakeholders with valuable assets in the mutual learning about service improvements.

Another major shift occurred in the collective articulation of the scope of co-creation and FLMs’ ambition to ‘promote health in every meeting’ with users. Examples of such collective reframing and reconceptualizing could be found in how FLMs defined and communicated PA co-creation through municipal websites and brochures, and in implementing meeting routines. This helped to unite the FLMs around a common ethics and language.

FLMs agreed that working together required a delicate balance between the user and service provider perspectives and influence—something FLMs related to as ‘the principle of balanced care’. There was growing acceptance that co-creation ethics required deep listening abilities to see and hear the individual. FLMs saw service routines, perhaps initially defined in dialogue with the user, as sometimes standing in the way. Routines provided ‘safety and predictability’, but risked undermining ad hoc co-creation opportunities and ‘passivating the citizen [who is assisted by PA services]’. Besides, FLMs showed increased awareness of utilizing new ways for user influence in assessing service practices and inspiring improvements, such as focus group and individual lived experiences and dialogue chains with users and service practitioners.

Nevertheless, FLMs saw actual user influence and balancing of powers as a remaining challenge, given formal and practical limitations. They recognized a need of continuous guidance as to when and how to actively apply co-creation and more time for reflexive learning dialogues with personnel.

Situated capabilities: from chaos restricting co-creation to increased manageability

At the pilot outset, the FLMs expressed some resentment about being unwillingly restricted from systematically implementing the aspired service norms. They blamed harsh service circumstances, such as lack of qualified personnel, service complexity, organizational fragmentation, context ambiguity and insufficient organizational support. FLMs also felt restricted by the organizational fragmentation in teams, their many responsibilities and conflicting value aspirations (economic efficiency, personnel wellbeing, user participation and service needs) and service contexts. Implementing co-creation in PA demanded specific service arrangements and skills to involve users with individual sets of disabilities. Notwithstanding this, personal assistant jobs lacked professional status and were low paid, making it hard to fill vacancies and combat constant personnel rotation and loss of knowledge. PA services were delivered by small teams of assistants with various backgrounds, where dysfunctional group dynamics often restricted individual co-creation ambitions.

FLMs’ efforts were focused on reactive behaviour commonly referred to as ‘extinguishing fires’ or conflicts among service personnel and users leaving little time and energy for systematic service improvement work. Being new in their roles, most FLMs experienced difficulties in navigating amidst available resources for support and treated service environments as ‘chaotic’. Repetitive difficulties in selecting adequate response to users’ needs and experienced limitations in standardized service practices fuelled FLMs’ feelings of disempowerment:

… the aim is good, but it [implementation plan] often becomes more of a tool to show the agencies that we do the documentation right more than empowering the individual.

… some are great at this [in implementation plans] while others can hardly manage. Some personnel depart from own values.

We do not have the right conditions [for development work].

Too many operational issues … too fragmented improvement work and support … no formal change leadership … we see our personnel once in three weeks … demanding user cases.

At T2, the collective narrative about the settings had undergone a transformation from chaos to more manageable complexity. Although service environments still remained unstable, FLMs now shared a more optimistic outlook ‘instead of focusing on the negative’—partly as an effect of knowledge gained, insights and initiatives in the joined-up dialogues, and partly because of positive organizational changes to support with administrative tasks and personnel recruitment.

FLMs admitted that increasing consistency in service language and ethics—resulting mostly from the joined-up dialogues—provided a more coherent frame of reference. Sensemaking collectively not only facilitated sharing experiences and perspectives, but also propelled joint implementation of the agreed service principles and improvements. This contributed to ‘the stronger sense of we’ and more coherence in service provision. FLMs now felt more comfortable with sharing their challenges and experienced increased collegiality and interest in guiding each other. Sensemaking contributed to insights that co-creation and change leadership variations will occur and there will always be space for reflection and improvement. Jointly testing several service improvements also increased FLMs’ understanding of organizational support potential.

Identities and relationships: from insecure to more aware and capable colleagues and leaders

Finally, we illustrate how FLMs perceived and articulated their identities and relationships to personnel and each other at T1 and T2.

Relationships with personnel

Early in the pilot, many FLMs felt challenged as change leaders by perceived gaps between service norms and personnel perspectives and abilities:

Our vision is not anchored among co-workers.

There is insufficient sense of responsibility [among personnel].

It is a challenge to reach out to them [PA personnel].

Relationships with each other

At T1, with many of FLMs being new to the job, the institutional memory was broken. In this situation, the practice of relying for support primarily within small FLM teams (of three to four people) highlighted their vulnerability and fragmentation. The relationships between teams were affected as they ‘did not care about the [challenges of the] others so much’, or wanted to expose their shortcomings. Even within the teams, while seeing colleagues as valuable resources, FLMs avoided overloading them with problems when crippled by urgent issues and perceived chaos, to avoid exhausting their support capacities. This increased isolation and ‘lack of coherence in [service] development work’, and decreased job satisfaction. The FLMs identified as rather lonely leaders who ‘experienced a longing for [broader] collaboration’, especially given the increasing ‘brain drain’.

At the time of T2, managers started seeing each other in a different light, more as teammates and resources to rely on in their own development and in challenging service situations. The mutual respect and ‘the sense of we’ had grown and they could now more openly share their successes and challenges with each other, thus creating a more open and supportive culture. Most importantly, FLMs increasingly recognized ‘joint responsibility for the PA area and the user’, and experienced being ‘less lonely and disempowered’, but instead as more helpful: ‘we pay attention to each other more, if somebody is not OK, ‘we try to take care of each other’.

Manager identities and abilities

Characteristic of the early narrative was also insufficient FLM abilities to prevent unhealthy group dynamics and act as transformational leaders without renouncing the health promoting approach:

I have an ongoing discussion with my personnel, but I have to constantly strive to make my personnel feel psychologically safe with each other in the group so that each of them dares to share their thoughts and interpretations of user situation and expressions, because if you do not have this you risk losing co-creation with the user due to unhealthy group dynamics.

At T2, FLMs articulated being confirmed and strengthened as leaders by their joined-up sensemaking dialogues. The area manager and action researcher adopted the asset-based approach and facilitated open reflections which raised their awareness that other colleagues also were facing challenging, even worse situations, and helped them to deal with their feelings of insufficiency: ‘I am not the worst leader after all’. The learning dialogues had also resulted in sharing experiences and insights about useful strategies for leading and boosting their personnel. For example, some FLMs used informal group leaders to translate their expectations to the rest of the personnel. Employing active listening, picking up and praising ongoing service improvements and involving personnel in sensemaking and setting service improvement goals were recognized as effective strategies.

The FLMs conveyed that new insights about their assets and skills, and possible coping strategies helped to ease the pressure they felt due to discrepancies between their leadership ambitions and the demanding service reality. It released more energy and confidence to address the service drawbacks that seemed possible to change and to focus on the positive developments. Personnel rotation challenged any efforts to strengthen professional ethics, but FLMs now felt better equipped to tackle it.

In sum, the facilitated sensemaking dialogues contributed to transforming the rather pessimistic and disabling service narrative and to re-empower FLMs as leaders and change agents.

Findings: sensemaking process

Below, we present the process of sensemaking, especially the approaches and strategies adopted by the studied action researcher when facilitating sensemaking and their impact on the service narrative and FLMs’ readiness for leading change. FLMs later assessed the success of joined-up dialogues as having ‘the right person in the right place at the right time’ and ‘a very successful approach at this development stage’.

Articulate, explore the needs and set a direction

The action researcher succeeded in ‘unfreezing’ change (Lippit et al. in Iveroth & Hallencreutz, Citation2016) in service culture by creating a psychologically safe environment and enabling inclusive and candid dialogues at an early pilot stage. The action researcher’s insistence on mental presence and ability of deep-listening without being judgemental encouraged FLMs to voice their concerns regarding their service situation, expectations and failures. In addition, the fact that the area manager viewed service culture change as a continuous process and trusted in the FLMs’ ability to agree on ‘what is right here and now’ contributed to an open atmosphere that ‘offered psychological comfort’ helping FLMs to articulate their initial disenchantment: ‘thanks to [the action researcher] our joint efforts resulted in a “creative arena”’.

While giving due attention and credit to the articulated service narrative, the action researcher also questioned whether their dominant narrative strengthened or weakened the FLMs as leaders and benefitted their staff. In parallel, the action researcher provoked the FLMs to explore service provision from the salutogenic perspective, i.e. ‘for whom this change is meaningful’—as a major yardstick for service improvement, thus clarifying why some ingrained approaches and practices were problematic, so enhancing their incitements for change. The action researcher also helped the pedagogical tutors employed at disability services to gather and collate PA user voices during a series of focus group interviews and later presented the findings to increase FLMs’ acceptance of changes. The action researcher urged FLMs to reflect and agree on the most meaningful improvements, boosting their sense of change ownership.

The action research strategies closely resembled change leadership through sensemaking—i.e. conversing candidly, facilitating learning by translating visions to service reality, and providing direction—as suggested in earlier research (Iveroth & Hallencreutz, Citation2016). Yet, our case stresses the importance of deep listening, wise balancing between acceptance and disturbance, and provoking new perspectives on service ethics, FLMs’ identities and relationships with the help of salutogenic assessment yardsticks to lead FLMs’ change into the ‘landscape of inertia’.

Improvise, structure and advance

In further dialogues, the action researcher and area manager together helped to advance change towards the collectively agreed service vision, by translating the organizational aims into their service situation, allowing for improvisation, unleashing the FLMs’ potential, encouraging and helping to prioritize and structure their actions—employing the suggested sensemaking strategies (ibid.).

Our case also evidenced the importance of the asset-based approach adopted by the action researcher who worked methodically to disturb FLMs’ identities as leaders debilitated by chaotic service circumstances—by drawing on examples of their assets and skills—and offering new perspectives. The action researcher encouraged FLMs to explore their assets and to ‘start by digging where you stand’, and to articulate and use their tacit knowledge of what works. Boosting FLMs’ identities as capable leaders with valuable assets urged them to reconsider their identities—gradually transforming the disempowering service narrative and enhancing FLMs’ motivation for change.

FLMs were also encouraged to explore the organizational resources they could tap into or adjust within the service regulatory frame to further boost their leadership and change agency. This led to innovative ideas on strengthening the co-creation norm in service ethics through study circles and tailored personnel trainings.

The action researcher retained FLMs in ‘the landscape of intertia’ by keeping the change process in motion and methodically working on its meaningfulness and feasibility. In the next step, the action researcher posed a battery of questions on responsibilities and needed resources (such as ‘how are we going to advance the process?’ and ‘on which organizational level should we look for the answer?’) to help diminish managerial sense of chaos and uncertainty, and systematize and advance otherwise sporadic and dispersed improvement activities. By requesting managers to use their ‘own words’ and definitions of what is true for them and ‘avoid unreflective obedience to empty concepts’ that may be imposed on them by the organizational vision, the action researcher motivated FLMs to own their change vision.

Look closely, guide and facilitate learning

To keep advancing the change, the action researcher closely examined their real-time context to stay relevant, and trained FLMs in situational awareness (ibid.), by helping them to notice signs of positive or negative developments in their service culture, and adjust accordingly their change efforts. For example, the action researcher encouraged and facilitated several FLM dialogues with PA decision-making officials. This helped break down communication barriers, deepen understandings and move towards shared professional ethics and new relational patterns.

To keep the FLMs in ‘the landscape of transformation’ and face its challenges and setbacks, later dialogues involved updates, reflections and guidance and search for constructive solutions. The action researcher trained the FLMs to feel comfortable in their change leader role by carefully suggesting relevant theoretical approaches, offering new interpretations, meanings and guidance in individual service situations. As a line of argument in all dialogues, the action researcher also guided them in how to apply the salutogenic approach in interactions with each other, other service professionals and in asset-based leadership to bridge the gap between the managers’ and employees’ service visions. The action researcher communicated that achieving a transformational effect in employee mindsets requires similar strategies as in their own sensemaking dialogues, such as active listening, salutogenic perspective and acknowledging their assets. This made the FLMs realize that not until they and their personnel understood their own importance and capabilities could service culture be fully transformed towards co-creation.

By setting an example of active and deep listening, the action researcher also encouraged FLMs to be critical listeners—to ‘speak out your concerns because silence kills [the work]’. These exercises served to widen their frames of reference and communication patterns.

Encourage self-evaluation, self-study and lead by example

The action researcher additionally employed self-assessment to help FLMs regularly and methodically reflect upon and assess their service culture improvement attempts by asking ‘where do we stand today?’, ‘for whom are these changes of value?’, ‘where can we see the health promotion in it?’, ‘or increased capabilities?’ helping to identify progress. Importantly, the action researcher and area manager praised good efforts, avoided judgment (ibid.) whenever facing visible lack of progress, but focused on deepening FLMs’ understanding, thus sustaining their motivation and change momentum. The action researcher additionally inspired the FLMs to start study circles that helped them to further explore change leadership and service ethics. The combination of ‘hard’, or goal-oriented, and ‘soft’, or sensemaking, leadership strategies employed by the area manager and the action researcher became an important FLM reference point for successful change leadership and facilitation.

As part of their leadership strategy after each dialogue session, the action researcher and the area manager circulated a dialogue summary in which they combined authentic FLMs’ voices with their own interpretations of the progress, challenges, agreed next steps and available resources to aid successful coping, highlighting the salutogenic factors (Antonovsky, Citation1996). Arguably, this tactic of tapping into group narrative through sensegiving also contributed to gradually rearticulating and reframing the service narrative.

In sum, reflective dialogues with the action researcher as a central sensemaking facilitator, were challenging in the beginning as the FLMs were unsure what to expect, felt pressured by urgent service matters and lack of time. Gradually, these meetings gained recognition as a valuable forum where everybody was given an opportunity to grow by ‘discussing issues that are not attended to anywhere else’. The FLMs felt enriched with new perspectives and strengthened in their leader identities and roles, which increased change manageability and incentives. The tactics of searching for SOC from both the service user and service provider perspective, combined with an asset-based approach, proved especially useful in narrowing the gap between the organizational and FLM service improvement visions and reduced resistance.

Conclusions

This article has explored the importance of facilitated sensemaking dialogues in preparing FLMs for methodical co-creation. The PA case represents a public service context perceived as complicated by weak professional identity, fragmented organizing and personnel turnover. This puts particular constraints on leadership towards a co-creation culture.

Our findings indicate that, to implement co-creation as a new norm and social innovation in disability services, neither regulatory policy steering nor delegation of change leadership mandate is sufficient. Situated service narratives at street level play an important role in defining FLM norms, identities and relationships. A pathological narrative weakening FLMs’ motivation and perceived abilities in change leadership may instead gradually be transformed to empower them for co-creation through sensemaking grounded in salutogenic approach.

While Aasen and Amundsen (Citation2013) argue that sensemaking in dispersed arenas often splits and obstructs change efforts, our findings emphasize the importance of joined-up dialogues, a facilitatory action researcher role and a more holistic approach towards managing service culture transformation grounded in the SOC perspective (Antonovsky, Citation1996). The study highlights the role of action researcher as a key sensemaking facilitator, undertaking sensegiving, sensetaking and sensebreaking roles in the interaction with targeted FLMs as change agents and leaders.

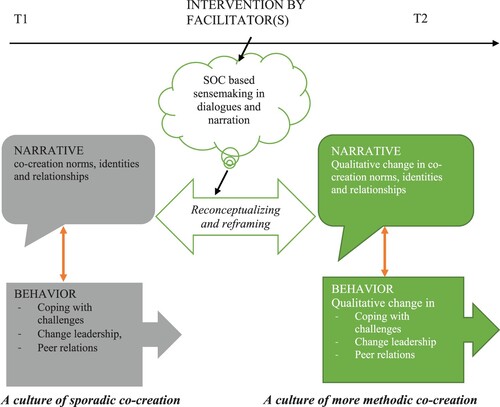

Our study evidences the usefulness of future-oriented collective sensemaking strategies to facilitate change, by moving from ‘the landscape of comfort’ to ‘the landscapes of inertia and transformation’, as suggested by earlier research (Iveroth & Hallencreutz, Citation2016). Our study highlights two complementary strategies as helpful in challenging FLMs’ situated service experiences. Bringing in citizens’ perspectives as service end-users helped FLMs to comprehend the meaningfulness of change. Additionally, the action researcher's ability to create an open, respectful atmosphere and to see and identify with individual perspectives and shortcomings through active listening mattered a great deal. Yet, the change anxiety among the FLMs was not relieved until their individual and joint assets and work experiences were recognized. The asset-based approach adopted by the action researcher contributed to a greater sense of change manageability and motivated FLMs to gradually reframe the service narrative by shifting their identities as change agents and leaders, thus altering their actions (see ).

Focus on increasing mutual understanding, meaningfulness and manageability of change—the cornestones of the salutogenic SOC framework—combined with an asset-based approach proved essential for supporting sensemaking of change.

To conclude, changing FLMs’ perceptions of their roles and abilities in leading change, and increasing a sense of coherence, was only possible after having recognized and accepted a pathogenically-oriented service narrative, which was also questioned and gradually reconceptualized and reframed with the help of theoretical and practical guidance in an iterative process of sensetaking, sensebreaking and sensegiving. In this complex change process, our findings confirm the usefulness of facilitated dialogues that wisely combine strategies exposed in research on leading change through sensemaking and narration combined with a salutogenic, asset-based approach in helping to transform managers’ perceptions of service ethics, identities and social relations to empower and motivate them in change leadership. In addition, our study evidences that action researchers may serve as key facilitators in aiding service culture change.

Acknowledgements

This study has received financing from the European Commission, the EU Framework Programme for Research and Innovation, Horizon 2020, within the project Co-creation in public service innovation in Europe (No. 770492).

References

- Aasen, T. M., & Amundsen, O. (2013). Innovation som kollektiv prestation. Studentlitteratur.

- Adelman, C. (1993). Kurt Lewin and the origins of action research. Educational Action Research, 1(1), 7–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/0965079930010102

- Ahrenfelt, B. (2013). Förändring som tillstånd: att leda förändrings- och utvecklingsarbete i företag och organisationer. Studentlitteratur.

- Antonovsky, A. (1996). The salutogenic model as a theory to guide health promotion. Health Promotion International, 11(1), 11–18. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/11.1.11

- Baron, S., Stanley, T., Colombian, C., & Pereira, T. (2019). Strengths-based approach: practice framework and practice handbook. Department of Health and Social Care.

- Batalden, M., Batalden, P., & Margolis, P. (2015). Coproduction of healthcare service. BMJ Quality & Safety, 25(7), 509–517. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2015-004315

- Bohm, D. (1996). On dialogue. Routledge.

- Bowman, J., & West, J. (2015). Values, ethics, and dilemmas. Public service ethics. Sage.

- Evers, A., & Brandsen, T. (2016). Social innovations as messages: democratic experimentation in local welfare systems. In T. Brandsen, S. Cattacin, A. Evers, & A. Zimmer (Eds.), Social innovations in the urban context. Springer.

- Fonseca, J. (2002). Complexity and innovation in organizations. Routledge.

- Gioia, D. A., & Chittipeddi, K. (1991). Sensemaking and sensegiving in strategic change initiation. Strategic Management Journal, 12(6), 433–448. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.4250120604

- Huemer, L. (2012). Organisational identities in networks: sense-giving and sense-taking in the salmon farming industry. The IMP Journal, 6(3), 240–254. http://hdl.handle.net/11250/93704

- Iveroth, E., & Hallencreutz, J. (2016). Effective organizational change: leading through sensemaking. Routledge.

- Jönköping kommun. (2016). 10 förbättringar från Dialogen. Socialtjänsten.

- Jönköping kommun. (2018). En sammanhållen socialtjänst. Socialtjänsten.

- Karlsson, M. (2019). Brukarkunskap och upphandling. In O. Segnestam Larsson (Ed.), Upphandlad. Idealistas.

- Lipsky, M. (1980). Street-Level Bureaucracy. Dilemmas of the Individual in Public Services. Russell Sage.

- Lüscher, L. S., & Lewis, M. W. (2008). Organizational change and managerial sensemaking: working through paradox. Academy of Management Journal, 51(2), 221–240. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2008.31767217

- McBeth, M. K., Jones, M. D., & Shanahan, E. A. (2014). The narrative policy framework. In P. Sabatier, & C. M. Weible (Eds.), Theories of policy process. Westview Press.

- Murray, R., Caulier-Grice, J., & Mulgan, G. (2010). The open book of social innovation. NESTA.

- Osborne, S. P. (2018). From public service-dominant logic to public service logic: are public service organizations capable of co-production and value co-creation? Public Management Review, 20(2), 225–231. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2017.1350461

- Osborne, S. P., Radnor, Z., & Strokosch, K. (2016). Co-production and the co-creation of value in public services: A suitable case for treatment? Public Management Review, 18(5), 639–653. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2015.1111927

- Ostrom, E. (1996). Crossing the great divide: coproduction, synergy, and development. World Development, 24(6), 1073–1087. https://doi.org/10.1016/0305-750X(96)00023-X

- Pestoff, V. (2009). Towards a paradigm of democratic participation: citizen participation and co-production of personal social services in Sweden. Annals of Public and Cooperative Economics, 80(2), 197–224. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8292.2009.00384.x

- SFS. (1993). The Act concerning support and service for persons with functional impairments. Ministry of Health and Social Affairs. https://www.independentliving.org/docs3/englss.html.

- Sinclair, S., Mazzei, M., Baglioni, S., & Roy, M. J. (2018). Social innovation, social enterprise, and local public services: Undertaking transformation? Social Policy Administration, 52(7), 1317–1331. https://doi.org/10.1111/spol.12389

- Socialstyrelsen. (2009). Swedish disability policy—service and care for people with functional impairments. Socialstyrelsen. https://www.mindbank.info/item/1201.

- Stigliani, I., & Ravasi, D. (2012). Organizing thoughts and connecting brains: Material practices and the transition from individual to group-level prospective sensemaking. Academy of Management Journal, 55(5), 1232–1259. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2010.0890

- Streatfield, P. (2001). The Paradox of Control in Organisations. Routledge.

- Torfing, J., Sørenssen, E., & Røiseland, A. (2016). Transforming the public sector into an arena for co-creation: barriers, drivers, benefits and ways forward. Administration and Society, 51(5), 795–825. https://doi.org/10.1177/0095399716680057

- Virtanen, P., & Stenval, J. (2014). The evolution of public services from co-production to co-creation and beyond. International Journal of Leadership in Public Services, 10(2), 91–107. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJLPS-03-2014-0002

- Weick, K. E., Sutcliff, K. M., & Obstfeldt, D. (2005). Organising and the process of sensemaking. Organization Science, 16(4), 409–421. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1050.0133