IMPACT

This article provides a way to promote more effective and equitable collaboration in the design and delivery of public services. Increasingly public services are designed with service users, but it is common for these provider–user endeavours to perform sub-optimally and/or to have negative outcomes. The authors offer a set of principles and a novel framework for applying them that have been designed to: firstly, mitigate the potential for sub-optimal and/or negative performance and, secondly, promote more positive processes and outcomes for provider–user collaborations. Improving provider–user collaboration in this way will ultimately lead to better design and delivery of public services.

ABSTRACT

Although Elinor Ostrom’s principles for collaborative group working could promote effective and equitable collaborative endeavours among diverse actors/stakeholders, they are largely untested in public service design and delivery. This article demonstrates how Ostrom’s principles could help to mitigate the potential for co-creating dis/value and instead support all involved to co-create systemic public value. The authors develop Ostrom’s work by proposing: an original, systemically-informed re-classification of Ostrom’s principles; that co-creation endeavours can be reconceptualized as a novel way of creating a ‘common pool resource’ and; that failure to adequately address the potential to co-create dis/value can lead to ‘tragedies of co-design’.

Introduction

In contributing a new development article to a Public Money & Management theme that is critically engaging with the parameters of public value co-creation and the potential for co-creating negative processes and outcomes, we aim to: acknowledge the potential of both the intentional and unintentional co-creation of dis/value; and offer theoretical developments that could both mitigate potential for co-creating dis/value as an outcome and offer means through which to negotiate dis/value if it occurs during a co-creation process.

We propose that Elinor Ostrom and colleagues’ principles for collaborative group working (Wilson et al., Citation2013) could promote effective and equitable collaborative endeavours among diverse actors/stakeholders but are as yet under-utilized and largely untested for this purpose in the context of public service design and delivery. We contend that the principles offer a means through which to mitigate the potential for co-creating dis/value and instead support all involved to co-create systemic public value. To facilitate translation of theory into practice, we develop Ostrom’s work in this article by proposing:

an original, systemically-informed re-classification of Ostrom’s principles;

that co-creation endeavours can be reconceptualized as a novel way of creating a ‘common pool resource’;

that failure to adequately address the potential to co-create dis/value can lead to ‘tragedies of co-design’.

Responding to the potential for co-creating dis/value

To avoid semantic arguments, we follow this theme’s guest editors in adopting the term ‘co-creation’. Like them, we appreciate that often this term is (not unproblematically) used interchangeably with ‘co-production’ and ‘co-design’ (see Williams et al., Citation2020), despite each of them having varying theoretical and disciplinary origins and definitions (Robert et al., Citation2021a; Brandsen & Honingh, Citation2018). Previously we have considered Ostrom’s principles in relation to co-design processes as a specific form of collaborative group work and how they could promote value co-creation (Robert et al., Citation2021b). We use the term ‘co-creation’ here in a broader sense—to describe the inclusion of service users and public contributors in public service work with the explicit intention of developing and improving services with local and experiential knowledge.

Cluley et al. (Citation2021) made key contributions to the conceptualization of public value by introducing two novel concepts embedded within a theoretical framework (assemblage theory) that recognizes the complex, interconnected, and not entirely predictable nature of systems. ‘Public value ethos’ describes ‘the prevailing assumption that the inclusion of service user voices in the delivery and improvement of public services creates individual and societal benefits’, while ‘dis/value’ is presented as ‘an umbrella term to capture the range of public value experiences that may not fit with the general perception that public value co-creation is a positive process for all’. Co-creation can be utilized to create value and address issues of (in)equity and (in)equality. However, the conceptual couplet of ‘public value ethos’ and ‘dis/value’ brings attention to, and offers lenses through which to interpret, the tendencies for co-creation endeavours to either be well-intentioned but naive and without wholly positive outcomes, or under-scrutinized tokenism. Both tendencies typically stem from a lack of due consideration given to the potential for co-creation to have detrimental outcomes. Like Cluley et al. (Citation2021), we do not dispute the potential for co-creating public value nor the ‘idealism and morality inherent within [the public value] ethos’. However, we recognize that this idealism and theoretical moral function can make it difficult to direct critical attention to the ‘participatory zeitgeist’ (Palmer et al., Citation2019) and accompanying proliferation of the use of the ‘co-’ prefix. This inhibits the improvement of participatory theory and practice and efforts to limit the co-creation of dis/value.

Unlike other forms of public service development, participatory practice is justified on both technocratic and moral grounds. That is, including public contributors/service users in service (re)design can help make services fit for purpose by addressing the needs and preferences of public contributors/service users and doing so is seen to in some way redress democratic deficits by providing those who are marginalized or excluded with a conduit to influence public services (Martin, Citation2009). These obviously positive rationales can lead to uncritical advocating for co-creation, especially as it is seen to address past failings in terms of exclusion and paternalism. More recently, this lack of criticality has been challenged. For instance, after Voorberg et al. (Citation2015) called co-creation a ‘magic concept’, Dudau et al. (Citation2019) called for ‘constructive disenchantment with the magic that surrounds co-design, co-production and value co-creation in public services’. Prior to this, and in the context of user involvement in welfare provision, Cribb and Gewirtz (Citation2012) questioned advocates presenting participatory practice as ‘ethically straightforward and as an unalloyed good’ and considered the ethical choices and dilemmas that are obscured by these discourses. Earlier still, Cooke and Kothari (Citation2001) asked if ‘participation’ was ‘the new tyranny’ as they reflected on the difficulties of being openly critical of participatory theory and practice and how acts and processes done in the name of participation ‘can both conceal and reinforce oppressions and injustices in their various manifestations’. As such, Cluley et al.’s (Citation2021) novel concepts fit within a growing literature on the so-called ‘dark side’ of participatory theory and practice (for example Williams et al., Citation2016; Citation2020; Plé & Cáceres, Citation2010; Steen et al., Citation2018; Fotaki, Citation2015), that we have contributed to ourselves (Williams et al., Citation2020).

Like others offering such critiques, the attention we give the dark side is not due to us being anti-participatory or against co-creation—much the opposite. We are driven by a recognition that the stated rationales of co-creation and the potential to co-create public value are often un(der)realized in, and sometimes completely unaligned with, practice. We use this recognition and ‘dark logic’ (Bonell et al., Citation2015) to develop ways to anticipate harmful mechanisms and outcomes associated with participatory interventions and to attend to the need to guard against them from the outset of projects. As such, we seek to find new and better ways to co-create public value that sufficiently attend to relevant moral and practical issues and offer means through which to both mitigate and negotiate the co-creation of dis/value. This led us to the work of Ostrom et al. (Citation1978) on self-governance and the collective management of common pool resources. Alford (Citation2014) proffered that Ostrom and colleague’s pioneering work on co-production (Ostrom et al., Citation1978; Parks et al., Citation1981) was ‘insufficiently explored’ by her and others within her career and that it could be ‘enriched by applying insights from other parts of her work’. We have certainly found this to be the case. Here we elaborate on how we have developed Ostrom’s theory with the intention of applying it to the practice of co-design and the task of co-creating public value.

Ostrom’s principles for collaborative group working: prospective and practical applications

Ostrom (Citation1990) demonstrated that certain conditions and ways of working facilitate groups of people to sustainably manage what she termed common pool resources. Ostrom defined common pool resources as consisting of natural or human-made resource systems (for example fisheries, forests, irrigation systems, bridges) that offer potential benefits to people and groups (for example flood management, food, income) and from which it is either impractical or too costly to exclude people from obtaining these benefits (for example policing fisheries to prevent overfishing). Without proper management, these resources are susceptible to over- and/or ill-use with detrimental social and ecological consequences (for example overfishing). In short, they are prone to ‘tragedies of the commons’ where individual self-interest leads to societal dysfunction (Hardin, Citation1968); what might otherwise be termed ‘dis/value’. From extensive empirical studies of the management of common pool resources (accessible via the CPR database at Center for Behaviour, Institutions and the Environment, Citation2021), Ostrom (Citation1990) distilled a set of eight design principles that largely explained the effectiveness of long-enduring collective management of common pool resources. Cox et al. (Citation2010) later evaluated 91 common pool resource case studies (including community forest governance in the Indian Himalaya, co-management of fisheries in Indonesia, Moroccan irrigation systems) and reported that the principles remained well supported empirically. However, the study used the principles as a theoretical framework through which to retrospectively analyse case studies rather than working with local groups to prospectively apply them. Later, working with Wilson et al. (Citation2013), Ostrom refined these principles and advocated for their prospective application to wider forms of collaborative group working (see ). To make the point, they explored the theoretical application of the principles within two contexts beyond Ostrom’s previous definition of common pool resources—education and urban neighbourhoods. They concluded ‘the core design principles can potentially serve as a practical guide for increasing the efficacy of groups in real-world settings’. Despite nearly a decade passing since this promising conclusion, the potential utility of prospectively applying these principles within co-creation endeavours is almost entirely untested.

Table 1. Elinor Ostrom’s design principles for collaborative group working.

In a recent publication, we proposed that some of the limitations of co-design as a service improvement approach in healthcare could be at least partially addressed by using Ostrom’s empirically-derived theory to re-conceptualize co-design through the lens of ‘common pool resources’ (Robert et al., Citation2021b). In terms of practice, we proposed using Ostrom’s eight design principles—and the relationships between them—as a heuristic to support the planning, delivery, and evaluation of future co-design projects. Ostrom paid little attention to the relationships between the principles in collaborative group working but we argue that viewing the co-creation of value from a systemic perspective (i.e. appreciating the relevance of the relationships between the principles) is imperative to mitigating and negotiating the co-creation of dis/value.

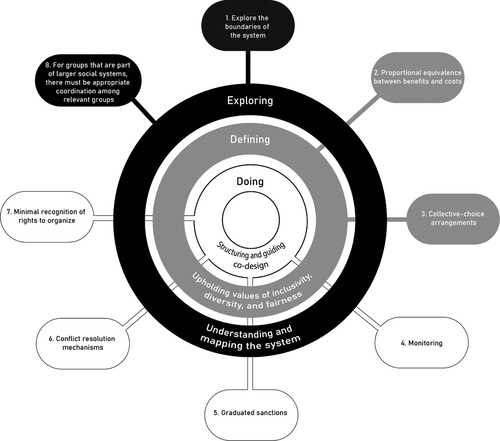

As the utility of prospective application of Ostrom’s principles is currently a largely theoretical proposition, for ethical and practical reasons we felt it best to first retrospectively apply them to a recent co-design project involving often marginalized and disengaged citizens in the USA, specifically citizens returning to the community from jail in Los Angeles County (see Mendel et al., Citation2019). Our findings indicated that, from a systemic perspective, the purposeful application of Ostrom’s design principles as a heuristic could usefully improve future endeavours to co-create value, mitigate the potential to co-create dis/value, and offer groups of collaborators a means to negotiate dis/value during the co-design process (Robert et al., Citation2021b). To support the transition of theory into practice, in our retrospective analysis we used systemic principles to re-classify Ostrom’s principles as we saw them relating to three distinct aspects of co-design: understanding and mapping the system; upholding values of inclusivity, diversity and fairness; structuring and guiding co-design (see ). This framing helps to anchor the principles in the practical tasks of co-creating which is useful as they can otherwise appear abstract.

We propose that there is potential in considering co-creation: first, as a means of developing and utilizing a form of common pool resource and, second, as a collaborative effort that would benefit from being informed by Ostrom’s design principles. That is, co-creation can be seen as a novel way of bringing together relevant actors/stakeholders within a system and ‘pooling’ their resources (for example experiential knowledge, labour, funding, networks/connections) in creative and constructive interactions—thus creating a ‘common pool resource’ that previously did not exist. The principles offer groups a heuristic that can and should be tailored to the specific contexts and tasks in which they are engaging. Indeed, Ostrom wrote of how, depending on context and objectives, any of the design principles could be implemented in more than one way and there was a need for groups to establish ‘auxiliary design principles’ in addition to the core principles, to support appropriate contextualization (Wilson et al., Citation2013).

Reconceptualizing the process of co-creation as a way of creating a common pool resource that requires collective management and applying Ostrom’s design principles to this task, also has the potential to enable more productive ways of working within complex systems (for example by integrating notoriously fragmented healthcare services which otherwise commonly reproduce dis/value). Reframing co-creation as an endeavour which brings together a diversity of actors/stakeholders (with the involvement of service users essential) to pool resources in an effort to create public value helps to highlight: firstly, who needs to be involved in co-creation efforts; secondly, what the limits and possibilities are for co-creating value, both from an actor/stakeholder-centric perspective but, also, as Cluley et al. (Citation2021) argue is necessary, by considering the wider systemic impact; and thirdly, what is necessary to sustain such efforts (and what the implications of not sustaining them may be).

Initiating co-creation endeavours with Ostrom’s principles as a heuristic to inform and guide (but not determine) the process and outcomes has the potential to support the achievement of both technocratic and moral rationales for co-creation. It does this by: providing a systemic and systematic approach to planning, delivering, and evaluating the co-creation of public value; making explicit issues of equity relating to involvement and participation; and explicitly addressing the potential to co-create dis/value and offering a means through which to negotiate unintentionally co-created dis/value (for example exploitative behaviour, interpersonal tensions). In practice, this will help groups to:

Identify who needs to be involved in any given co-creation process, including highlighting those who are missing/excluded (Principles 1 and 8).

Recognize the uniqueness and importance of each actor’s/stakeholder’s contribution (Principles 1, 2 and 8).

Acknowledge that power is unequally distributed throughout systems and that this can/will inform the ‘doing’ of co-creation (Principles 2, 3 and 7).

Identify and address exploitative participation and negotiate interpersonal tensions (Principles 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 and 7).

Recognize how the contributions of each actor/stakeholder, and collaborations between them, relate to the overall aim of service (re-)design/improvement (Principles 1, 2 and 8).

Develop a sense of collective identity and action and address issues of sustainability by promoting long-term planning and equitable approaches to co-creating and managing value (Principles 1, 2, 3, 7 and 8).

No panacea: a heuristic to be applied and evaluated

Consistent with Ostrom’s (Citation2010) conclusions, we propose that applying Ostrom’s design principles as a heuristic to support planning, delivery, and evaluation could support the co-creation of value by groups encompassing public contributors/service users and multiple service providers within and/or across systems. To support this, we have expanded the concept of common pool resources, demonstrated how Ostrom’s principles can be applied systemically in the context of public service (re-)design and delivery, and contributed the ‘tragedies of co-design’ concept to the theorization of dis/value. Prospective application of Ostrom’s design principles in the context of public service (re-)design and delivery is rare but has the potential to promote the co-creation of value and both mitigate and negotiate the co-creation of dis/value.

However, in line with Ostrom’s own aversion to panacean thinking in applied research (Ostrom et al., Citation2007; Ostrom, Citation2007), we do not offer Ostrom’s principles, nor our theoretical developments, as panacea to the challenges of co-creation or the co-creation of dis/value. Neither are we ignorant of the critiques of Ostrom’s underpinning theory, including a perceived lack of consideration of the potential of macro-level interventions, an over-reliance on the rational behaviour of individuals, and a lack of attention given to the power-relations between society and government (Herzberg et al., Citation2019; Singleton, Citation2017; Schauppenlehner-Kloyber & Penker, Citation2016). Rather, we offer them as a heuristic that, our early analysis indicates, may support the co-creation of value, and promote adequate attention being given to the necessity of mitigating and negotiating the co-creation of dis/value. Given the theoretical promise of applying the principles in this way, we are now calling for critical engagement with, and thoughtful interpretation and application of, this theory in a variety of contexts. Their utility will not be universal. Different contexts and collaborations have unique requirements and present different opportunities; there remains much to be learnt from attempts to engage with, interpret, and prospectively apply these principles in a diverse range of contexts. For those interested in translating theory into practice, we recommend all participants in any given collaboration discussing the design principles early and transparently and allowing sufficient time to adapt the principles to the context and purpose of the group. Their effectiveness should be assessed in terms of whether and/or how they supported the co-creation of public value and/or mitigated/negotiated the co-creation of dis/value. Such evaluation is essential to building upon the theoretical promise we have demonstrated with the necessary empirical evidence to properly assess whether and how this potential can be realized.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Alford, J. (2014). The multiple facets of co-production: Building on the work of Elinor Ostrom. Public Management Review, 16(3), 299–316.

- Bonell, C., Jamal, F., Melendez-Torres, G. J., & Cummins, S. (2015). ‘Dark logic’: Theorizing the harmful consequences of public health interventions. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 69(1), 95–98.

- Brandsen, T., & Honingh, M. (2018). Definitions of co-production and co-creation. In Co-production and co-creation: engaging citizens in public services. Routledge.

- Center for Behaviour, Institutions and the Environment. (2021). Arizona State University. CPR database. https://seslibrary.asu.edu/cpr.

- Cluley, V., Parker, S., & Radnor, Z. (2021). New development: Expanding public service value to include dis/value. Public Money & Management, 41(8), 656–659. DOI: 10.1080/09540962.2020.1737392

- Cooke, B., & Kothari, U. (2001). The case for participation: the new tyranny? In Participation: the new tyranny? Zed Books.

- Cox, M., Arnold, G., & Tomás, S. V. (2010). A review of design principles for community-based natural resource management. Ecology and Society, 15(4).

- Cribb, A., & Gewirtz, S. (2012). New welfare ethics and the remaking of moral identities in an era of user involvement. Globalisation, Societies and Education, 10(4), 507–517.

- Dudau, A., Glennon, R., & Verschuere, B. (2019). Following the yellow brick road? (Dis)enchantment with co-design, co-production and value co-creation in public services. Public Management Review, 21(11), 1577–1594.

- Fotaki, M. (2015). Co-production under the financial crisis and austerity: A means of democratizing public services or a race to the bottom? Journal of Management Inquiry, 24(4), 433–438.

- Hardin, G. (1968). The tragedy of the commons. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1126/science.162.3859.1243.

- Herzberg, B., Boettke, P. J., & Aligica, P. D. (2019). Ostrom's tensions: reexamining the political economy and public policy of Elinor C. Ostrom. Mercatus Centre at George Mason University.

- Martin, G. P. (2009). Public and user participation in public service delivery: Tensions in policy and practice. Sociology Compass, 3(2), 310–326.

- Mendel, P., Davis, L. M., Turner, S., et al. (2019). Co-Design of Services for Health and Reentry (CO-SHARE). RAND Corporation. DOI: https://doi.org/10.7249/RR2844.

- Ostrom, E. (1990). Governing the commons: the evolution of institutions for collective action. Cambridge University Press.

- Ostrom, E. (2007). A diagnostic approach for going beyond panaceas. Proceedings of the national Academy of Sciences, 104(39), 15181–15187.

- Ostrom, E. (2010). Beyond markets and states: Polycentric governance of complex economic systems. American Economic Review, 100(3), 641–672.

- Ostrom, E., Janssen, M. A., & Anderies, J. M. (2007). Going beyond panaceas. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 104(39), 15176–15178.

- Ostrom, E., Parks, R. B., Whitaker, G. P., & Percy, S. L. (1978). The public service production process: A framework for analyzing police services. Policy Studies Journal, 7, 381–9.

- Palmer, V. J., Weavell, W., Callander, R., Piper, D., Richard, L., Maher, L., Boyd, H., Herrman, H., Furler, J., Gunn, J., & Iedema, R. (2019). The participatory zeitgeist: An explanatory theoretical model of change in an era of coproduction and codesign in healthcare improvement. Medical Humanities, 45(3), 247–257.

- Parks, R. B., Baker, P. C., Kiser, L., Oakerson, R., Ostrom, E., Ostrom, V., Percy, S. L., Vandivort, M. B., Whitaker, G. P., & Wison, R. (1981). Consumers as co-producers of public services: Some economic and institutional considerations. Policy Studies Journal, 9(7), 1001–1011.

- Plé, L., & Cáceres, R. C. (2010). Not always co-creation: Introducing interactional co-destruction of value in service-dominant logic. J Serv Mark, 24(6), 430–7.

- Robert, G., Donetto, S., & Williams, O. (2021a). Co-designing healthcare services with patients. In The Palgrave handbook of co-production of public services and outcomes. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Robert, G., Williams, O., Lindenfalk, B., Mendel, P., Davis, L. M., Turner, S., … Branch, C. (2021b). Applying Elinor Ostrom’s design principles to guide co-design in health(care) improvement: A case study with citizens returning to the community from jail in Los Angeles County. International Journal of Integrated Care, 21(1), 7. DOI: http://doi.org/10.5334/ijic.5569

- Schauppenlehner-Kloyber, E., & Penker, M. (2016). Between participation and collective action—from occasional liaisons towards long-term co-management for urban resilience. Sustainability, 8(7), 664.

- Singleton, B. E. (2017). What’s missing from Ostrom? Combining design principles with the theory of sociocultural viability. Environmental Politics, 26(6), 994–1014.

- Steen, T., Brandsen, T., & Verschuere, B. (2018). The dark side of co-creation and co-production: seven evils. In Co-production and co-creation: engaging citizens in public services. Routledge.

- Voorberg, W. H., Bekkers, V. J., & Tummers, L. G. (2015). A systematic review of co-creation and co-production: Embarking on the social innovation journey. Public Management Review, 17(9), 1333–1357.

- Williams, B. N., Kang, S.-C., & Johnson, J. (2016). (Co)-contamination as the dark side of co-production: Public value failures in co-production processes. Public Management Review, 18(5), 692–717.

- Williams, O., Sarre, S., Papoulias, S. C., Knowles, S., Robert, G., Beresford, P., Rose, D., Carr, S., Kaur, M., & Palmer, V. J. (2020). Lost in the shadows: Reflections on the dark side of co-production. Health Research Policy and Systems, 18.

- Wilson, D. S., Ostrom, E., & Cox, M. E. (2013). Generalizing the core design principles for the efficacy of groups. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 90, S21–S32.