IMPACT

Financial, performance and workload pressures on public services are increasing. Methods which enable practitioners to pool together and reflect on ‘practical wisdom’ to make better decisions in the navigation of complexity have the potential to improve the practitioner and service user experience and enable more effective targeting of resource-intensive interventions. This article contributes to the improved understanding of the practicalities, limitations and opportunities of surfacing and sharing tacit knowledge in the public sector environment. It will be of value to healthcare and social care practitioners, commissioners, service managers, educationalists and organizational development leads.

ABSTRACT

Public services operate in conditions of complexity. Practitioners and service users can never be certain of the impact or outcome of a course of action and, consequently, responsible failure must be supported. A new methodology for enabling public service professionals to navigate the complexity of their practice is introduced in this article: ‘learning communities’ (LCs). Drawing from developmental applications of this methodology, the authors describe how LCs provide environments for talking authentically about uncertainties and mistakes with the purpose of collective improvement, and draw parallels with similar methods of community co-creation. The way that LCs tackle two key elements of the public sector’s learning capacity noted in the literature—structure and culture—is explained.

Introduction

The public sector is confronted with complex problems which span traditional operational boundaries and require innovation in working practices. At the macro level, large-scale ‘wicked issues’ like climate change or population ageing have driven change in structures, processes and policies. It can be argued, however, that greater complexity manifests at the micro level, in what Schon (Citation1983) described the ‘swampy lowlands’ of practice, where practitioners engage in tackling complex problems without sufficient evidence or experience to identify best practice. Complexity requires openness to learning and responsible failure, and management practices which enable practitioners to navigate the ambiguity and uncertainty of their practice. However, in spite of many efforts and methods to support organizational learning in the public sector, two key barriers are highlighted: structure and culture (Moynihan & Landuyt, Citation2009; Nutley & Davies, Citation2001).

Recent literature has advocated alternative forms of adaptive and transformative leadership in the public sector to tackle cultural barriers to learning and promote tolerance for responsible failure (Gigerenzer, Citation2014; Hartley & Rashman, Citation2018). The intended result is to create what Gigerenzer (Citation2014) describes as ‘positive error culture’, where practitioners can speak openly about their uncertainties and mistakes, and where such errors are viewed within organizations as a chance to learn and improve, rather than a signal of poor performance. In complex environments, positive error culture enables collective reflection about the reality of practice and ‘what really works’, rather than the theoretical ‘what ought to work’. At a collective level, this cultural state would provide the basis for authentic conversations among peers and the potential for improved problem-solving where practitioners can describe and share their practical wisdom about complex cases where traditional evidence is scant or contested.

Other organizational learning scholars have taken a primarily structural view of learning—considering that learning can be promoted through redirection of work processes and the creation of organizational modalities which create a space for learning (for example Mintzberg, Citation1979). Here the literature also documents many structural impediments to learning in public organizations. Public services cannot ‘shut off’ services to conduct experiments, nor can they deviate significantly from established (often statutory) processes to explore new ways of operating. The public sector is concerned with improving a multidimensional concept of public value (Moore, Citation1995; Hartley et al., Citation2019) reflective of democratic, social and cultural values which public organizations are expected to uphold simultaneously. A key feature of public service professionals’ work is therefore to negotiate a course of action between multiple and potentially competing goals. In this context, the professional standards and competencies of public service work become porous and moving, requiring continual negotiation among communities of peers (Wenger, Citation1998). In addition to learning-conducive cultures, public service practitioners require the spaces to negotiate the complexity of their practice, and to feed into the development of new organizational practices and processes.

The learning communities approach

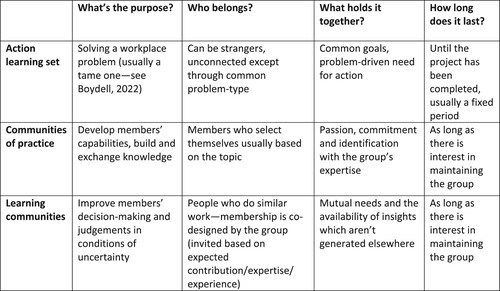

While the question of ‘do public sector organizations learn?’ (Barrados & Mayne, Citation2003) can been answered in the affirmative, reviews of organizational learning in the public sector note adverse organizational cultures and a lack of learning structures and processes as barriers to its learning capacity (Rashman et al., Citation2009; Gibson et al., Citation2009; Moynihan & Landuyt, Citation2009; Hartley et al., Citation2019). We introduce a novel ‘learning community’ (LC) concept for addressing both of these challenges and supporting the promotion of learning cultures and structures and processes among public service professionals, drawing from prior prototypes and applications of the LC model. We also explore how an LC approach (including purpose, who belongs, what holds it together) compares to and differs from other collective modes of learning, including action learning sets and communities of practice, to help consider its novelty ().

Figure 1. Comparing formats for collective learning (adapted from Wenger & Snyder, Citation2000, with additional acknowledgement of Catherine Dale for her iteration).

An LC is ‘a group of peers who come together in a safe space to reflect and share their judgements, uncertainties and experiences about their practice and to co-create ideas to collectively improve’ (Wilson & Lowe, Citation2018). Drawing from social learning theory and approaches like communities of practice (Lave & Wenger, Citation1991), they were designed to enable peers to shape for themselves what is needed to create a genuinely robust and safe space to share the detail of their work, challenges and uncertainties and enable collective learning and improvement. Communities of practice, while invested in knowledge sharing and knowledge creation, are typically free-flowing, larger and less local to the practices under consideration (Dewar & Sharp, Citation2006), and membership is self-selected, based on a common interest, not an instrumental contribution to the question posed by a convenor (see ).

The participatory arts sector origins of the LC approach are distinctly relational and systemic compared those of action-orientated learning processes like action learning sets. Action learning is broadly defined as ‘learning from concrete experience and critical reflection on the experience through group discussion, trial and error, discovery and learning from and with each other’ (Zuber-Skerritt, Citation2002, pp. 114–115) and, although relational in nature, participants do not need to be connected to each other’s problems, except through a common (but not necessarily shared) experience (see ). The focus on action is driven by an intention to make new behaviours ‘stick’ when traditional forms of organizational learning fail to generate change. While LCs share a positive error ethos, they often start with more abstract, less specific, and more complex questions (double and triple loop questions), aiming for deep cultural shifts in practice, not just action, and the building and convening connections and relationships.

Phases of an LC

The first LC phase involves work to legitimize and signal the importance of the LC through engagement with ‘sponsors’, such as senior leaders. This work is essential to establish its relevance to purpose or mission by creating an authorizing environment and negotiating arrangements and principles including agreeing the community’s constituency and surfacing any other expectations for the LC that a sponsor may have.

The second phase is a co-design process in which the initial LC session is convened, organized around the question: ‘What is needed to create a safe space to have authentic conversations about this work?’ In previous deployments, this has led to decisions about the new groups’ proposed membership and co-design of ground rules to govern the operation of the new group. This co-design also seeks to enable a process of mutual accountability.

Phase three is the facilitation of the LC to create space for open conversation about how and why participants choose to make particular professional judgements in their practice. Depending on what was agreed in the codesign session, the way each group explores participants’ practice will vary and evolve over time but will usually feature storytelling to illustrate an issue, description of practice, and discussion about uncertainties and doubts regarding practice.

LCs are built on principles of reflection and learning for participants but also for the organization or sector, so the fourth phase is reviewing and reflecting, both in action and on action (Schon, Citation1983), encouraging participants to review their experience of the session and contribute ideas for improving future meetings. These are commensurate with action learning set practices and procedures.

Given the relationships between LCs and communities of practice (as both represent modes of social learning) and LCs and action learning sets (as both represent a form of learning process), we have summarized the distinctions in .

Discussion

Building on prior applications of LCs, we used the concepts of structure and culture introduced previously to analyse how LCs can nurture conditions for learning. While that structure and culture are interdependent concepts (Moynihan & Landuyt, Citation2009), we nonetheless found value in their use as organizing themes.

Culture

LCs provide practitioners with an opportunity to ‘bring out into the open’ conversations about the uncertainty and complexity in their work. Through the development of trust over time, a ‘safe space’ can be created where participants are able to engage in honest discussions about their experiences which include narratives of when things weren’t successful, thus normalizing the discourse around making mistakes.

LCs offer opportunities to consider what accountability can look like and mean: peers co-create a shared understanding of what constitutes ‘good practice’ which is informed by professional standards and sector aims but is also rooted in the realities of the complex environment in which public services operate, where the results of an intervention or action cannot be predicted with certainty. Such horizontal forms of accountability can offer an alternative approach to top-down control, and the co-design phase of an LC can begin to unpick the complex entanglement of accountability and learning, which have been found to be a source of confusion and conflict. Distinct from action learning sets and communities of practice, each member has a purpose and a role in their participation, more similar to a formal work group. These foci on uncertainty and complexity and accountability for learning are not explicit in other forms of collective learning.

LCs can influence assumptions, values and norms through the normalization of learning (May et al., Citation2018) and becoming an integral part of organizational life and part of ‘the way we do things around here’ (Deal & Kennedy, Citation1983). The initial sponsor gives ‘permission’ for the creation of an LC, thus sending a signal of the cultural importance of learning.

Structure

LCs create a space dedicated to learning and adaptation in the organization. This provides a parallel structure where issues can be surfaced which otherwise would not be afforded the space; participants are given the opportunity to discuss the ‘how’ not just the ‘what’ of their practice (Wilson & Lowe, Citation2018). LCs therefore have the potential, after becoming established and recognized in their organizations, to provide a forum for practice innovation. For instance, LCs can provide a platform for the development and formalization of a ‘system change associate’ role (French & Lowe, Citation2018).

In their regularity LCs provide a structure which motivates reflective practice and the routine adoption of learning into professional practice. This gives participating professionals the ability to bridge what is learned in LCs with their own practice, providing the opportunity for learning to translate into changes in practice.

These sorts of communities, including Wenger’s (Citation1998) communities of practice, rarely happen spontaneously and certainly require intentional action and a focus on organizational learning. The LC model offers a way of systematically supporting the creation of a peer learning space which is of relevance to daily life and not something which is isolated from practice. We propose this means that practitioners are not only able to adapt to changes in policy and organizing structures, their actions taken during the LC process influence organizational structuring, thus making learning an integral part of public service life.

Conclusion

Learning is a necessary faculty for practitioners to make decisions in conditions of uncertainty and complexity. LCs foster learning cultures which promote complexity-informed learning and decision-making through responsible failure and focus more on the conditions for learning accountability. LCs provide a safe space for practitioners to become sensitized to practice, and for tensions, changes and uncertainties to be worked through. In contrast, formal work groups and action learning sets focus on specific workplace problems and can dissolved when the project is complete, or the problem is solved, therefore can represent simple or complicated problems. Communities of practice can convene without specific problems but have a field of interest about which members would like to learn more.

Findings from the literature suggest that learning often lacks a structural place within public organizations. While many forms of social learning provide a dedicated space for learning aimed at bridging learning and practice, LCs assemble as a platform for change, attending to the third order nature of socio-technical change including the co-design of learning structures and infrastructures.

Over time, these concerns can help to normalize learning in their broader organization becoming part of integral organizational structures and processes, thus sustainably dismantling barriers to collective improvement. Further research might explore in greater detail the architecture which LCs can offer which support learning, and what this can look like in different contexts. Meanwhile, practitioners are invited to experiment with an LC approach to explore its value in creating new spaces for learning in their own contexts.

Acknowledgement

The Learning Community Facilitator Development Programme was funded by an impact acceleration award from the ESRC, hosted by Newcastle University’s Centre for Knowledge, Innovation, Technology and Enterprise (KITE).

References

- Barrados, M., & Mayne, J. (2003). Can public sector organizations learn? OECD Journal on Budgeting, 3(3), 87–104.

- Boydell, T. (2022). Relational Action Learning. Action Learning: Research and Practice, 19(2), 193–195.

- Deal, T. E., & Kennedy, A. A. (1983). Corporate cultures: The rites and rituals of corporate life. Addison-Wesley.

- Dewar, B., & Sharp, C. (2006). Using evidence: How action learning can support individual and organizational learning through action research. Educational Action Research, 14(2), 219–237.

- French, M., & Lowe, T. (2018). Place action inquiry, our learning to date. Lankelly Chase Foundation.

- Gibson, C., Dunleavy, P., & Tinkler, J. (2009). Organizational learning in government sector organizations: literature review. LSE Policy Group.

- Gigerenzer, G. (2014). Risk savvy: How to make good decisions. Viking.

- Hartley, J., Parker, S., & Beashel, J. (2019). Leading and recognizing public value. Public Administration, 97(2), 264–278. https://doi.org/10.1111/padm.12563

- Hartley, J., & Rashman, L. (2018). Innovation and Inter-organizational learning in the context of public service reform. International Review of Administrative Sciences, 84(2), 231–248.

- Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge University Press.

- May, C. R., Cummings, A., Girling, M., et al. (2018). Using normalisation process theory in feasibility studies and process evaluations of complex healthcare interventions: A systematic review. Implementation Science, 13, 80.

- Mintzberg, H. (1979). The structuring of organizations. Prentice-Hall.

- Moore, M. H. (1995). Creating public value: strategic management in government. Harvard University Press.

- Moynihan, D. P., & Landuyt, N. (2009). How do public organizations learn? Bridging cultural and structural perspectives. Public Administration Review, 69(6), 1097–1105.

- Nutley, S. M., & Davies, H. T. (2001). Developing organizational learning in the NHS. Medical Education, 35, 35–42.

- Rashman, L., Withers, E., & Hartley, J. (2009). Organizational learning and knowledge in public service organizations: A systematic review of the literature. International Journal of Management Reviews, 11(4), 463–494.

- Schon, D. (1983). The reflective practitioner: how professionals think in action. Ashgate.

- Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of practice: Learning, meaning and identity. Cambridge University Press.

- Wenger, E. C., & Snyder, W. M. (2000). Communities of practice: The organizational frontier. Harvard business review, 78(1), 139–146.

- Wilson, L., & Lowe, T. (2018). The learning communities handbook. https://www.humanlearning.systems/uploads/The-Learning-Communities-Handbook.pdf.

- Zuber-Skerritt, O. (2002). The concept of action learning. The learning organization, 9(3), 114–124.