IMPACT

Making sure that citizens and users are key actors in public value co-creation is a challenge. A particular difficulty is how to include marginalized citizens and users to give them a voice in deliberating public value. This article discusses how kindergartens can be used as a platform for co-created policy-making. The authors provide practical advice on how to facilitate socially-inclusive public encounters with relevant policy stakeholders. By using a universal welfare institution as the platform, the article shows how public participation in co-creation can be more socially-inclusive and fair.

ABSTRACT

This article explores collaborative ‘platforms’ to transform individual experiences of dis/value into socially-inclusive community development. By connecting a participatory action research process to processes of policy-making in Norwegian local government, the article studies how social inclusion can be negotiated, formulated and co-created as a public value based in kindergartens as platforms for co-created policy-making. Norwegian kindergartens, embedded in the national welfare regime, have unique properties for deepening the participation of parents, especially socially marginalized parents. This article contributes to deepening our understanding of public institutions as co-creation platforms and the processual dynamics of socially-inclusive policy-making.

Introduction

While the public discourse tends to understand co-creation as a value in itself, recent academic debate has questioned this core premise. Formal lack of access, social or cultural barriers or unwillingness among citizens mean that individually co-created values cannot be synonymous with public values (Cluley et al., Citation2020). Although public quality-of-life outcomes are put forward as the ultimate public value (Loeffler & Bovaird, Citation2020), capabilities to achieve wellbeing are unequally distributed in and between populations (Prilleltensky, Citation2020; Sen, Citation2005). Moreover, public services might also harm some individuals or groups (Lightbody & Escobar, Citation2021; Loeffler & Bovaird, Citation2020): for example if pupils are bullied at school or if services are disproportionately delivered according to citizens’ needs. Cluley et al. (Citation2020, p. 2) describe such tensions as ‘dis/value’, coined as ‘an umbrella term to capture the range of public value experiences that may not fit with the general perception that public value co-creation is a positive process for all’. Inclusive participation is acknowledged as a key driver to impact public policy and equitable wellbeing outcomes (Prilleltensky, Citation2020; Young, Citation2000), yet the practical implications remain unclear (Fung, Citation2015; Heimburg & Cluley, Citation2020; Loeffler & Bovaird, Citation2020).

Based on these considerations, we wanted to understand the complex relationship between public dis/value as an individual experience and public value creation through collective policy development. Scholars have argued that transforming co-creation of individual values into public values calls for something extra, such as strategy and strategic management (Hartley et al., Citation2019; Ongaro et al., Citation2021) or a wider ecosystem of capabilities (Strokosch & Osborne, Citation2020). This article explores, through a participatory action research (PAR) design, the extent to which the literature on collaborative platforms (Ansell & Gash, Citation2018) can shed new light on the transformation of co-created dis/value into public value governance. The platform we chose is a classic public service organization (PSO): the kindergarten. The article explores the extent to which kindergartens can serve as platforms for extensive collaboration with goals that exceed the formal goals of the service organization.

Kindergartens are enduring welfare services and therefore suitable for co-creation (Vamstad, Citation2012). In the Norwegian context, even though kindergartens can be public or private, in both cases they are funded and regulated by a common legal framework in which local government plays a key role. This implies a line of governance from the stand-alone kindergarten to local governance and planning. Although still scarce, previous research has focused on the potentials for individual and micro-level co-creation in kindergartens and communities (Heimburg et al., Citation2021; Vamstad, Citation2012).

In this article, we address a neglected dimension in the co-creation literature—how sharing and deliberation of individual experiences of dis/value can lead to collective policy-making. The question that guided our research was: How can kindergartens, as collaborative platforms, support deliberations of dis/value into socially-inclusive community development? To ground our research question, in the next section we explain key concepts and contexts for the study.

Positioning co-creation and collaborative platforms

Co-creation, understood as a distinct type of collaboration, is defined as: ‘a distributed and collaborative pattern of creative problem-solving that proactively mobilizes public and private resources to jointly define problems and design and implement solutions that are emergent and seek to generate public value’ (Ansell & Torfing, Citation2021). Our use of the term ‘co-creation’ in this article embraces various aspects of multi-actor collaborations in policy-making processes which intend to support social inclusion to achieve community wellbeing as a public value.

Platforms for co-created policy-making are considered to be a viable approach to rekindling the relationship between citizens and the state beyond a transactional and service-oriented approach to public value creation (Ansell & Torfing, Citation2021). Collaborative platforms are frameworks that allow collaborators (for example citizens, users, stakeholders, providers) to undertake a range of activities, often creating de facto standards for decision-making—and forming entire ecosystems for collaboration (Ansell & Torfing, Citation2021). According to Ansell and Gash (Citation2018), collaborative platforms fill a particular niche in the world of governance; they specialize in facilitating, enabling and, to some degree, regulating ‘many-to-many’ collaborative relationships.

The academic literature points to various types of platforms, such as digital platforms (Kenney & Zysman, Citation2015), temporary project organizations (Lundin & Söderholm, Citation1995), networks (Sørensen & Torfing, Citation2009) and stand-alone organizations (Ansell & Gash, Citation2018). Different types of platforms are not neutral to the contents and outcomes of co-creation as they influence which actors becomes involved, how they interact and with what result.

Positioning wellbeing and social inclusion

Social inclusion and the imperative of ‘leaving no one behind’ (UN, Citation2016) is a central starting point. In our research, we followed Prilleltensky’s (Citation2020) concept of wellbeing as a personal and public value that is dependent on ‘mattering’, referring to social opportunities to feel valued by, and to add value to, self, others, work and community. ‘Mattering’ relates to developing capabilities that are constitutive for what people are able to do and to be (Sen, Citation2005). ‘Social inclusion’ refers to experiences of value at the personal and interpersonal levels, understood as being physically and socially included in various arenas, to feel connected and recognized, and to entitle wellbeing agency for all (individuals’ ability to impact on goals they value). However, outcomes are ecologically dependent on the processes at the organizational and societal levels as well (Heimburg & Ness, Citation2020; Prilleltensky, Citation2020; Sen, Citation2005).

In this article, we use three interlinked theoretical perspectives to conceptualize social inclusion: social justice (Fraser, Citation2009); relational co-ordination (Bolton et al., Citation2021; Gergen et al., Citation2001); and transforming complex, adaptive systems (Bartels et al., Citation2020; Bronfenbrenner, Citation1979).

Positioning kindergartens and the research site

In the Nordic welfare regime, local governments are key actors in providing welfare and promoting public health (Pedersen & Kuhnle, Citation2017). Universal access is embedded in the welfare system to provide social security and wellbeing. Kindergartens are vital welfare institutions in this regard. In Norway, kindergartens have gone through radical changes over recent decades. From 2006, all children over the age of one were given the legal right to access to a kindergarten. By these new regulations, kindergartens became a universal service, acting as the first step of the educational system (Haug & Storø, Citation2013). Even though all kindergartens are regulated by the same rule of law, a slight majority of institutions are still private. Currently, 92.2% of children enter kindergartens in Norway (Statistics Norway, Citation2020). Parents have legal rights to ‘be heard’ and ‘participate’ although, in practice, only a few parents tend to be active and involved (Trætteberg & Fladmoe, Citation2020).

The research site for our study was a mid-size Norwegian municipality with approximately 20,000 inhabitants. In 2014, this municipality adopted public health and equity as main policy goals in their municipal masterplan, and co-creation was described as a viable approach. However, key public health issues were still unsolved, and mainstreaming socially-inclusive co-creation was still not achieved. This implementation gap contributed to commissioning the present research project. In the municipality, 97.2% of the children were enrolled in kindergartens (higher than the national average). This high coverage makes the kindergarten a suitable platform for experimenting with socially-inclusive pathways to deliberate and formulate public values, and mobilize joint action.

The first author of this article worked in public health and strategic planning in the participating municipality. The second author had two different roles in this study. First, she participated as a parent and generated data. Second, she worked as a co-researcher to amplify the voices and presence of citizens that tend to be marginalized from taking part in traditional ways of doing policy-making. The third author also had a double role in the project as supervisor of the first author and participating directly in the research as a member of an outsider researcher group, maintaining an analytical distance to the local agenda.

Methods, data and analytical procedure

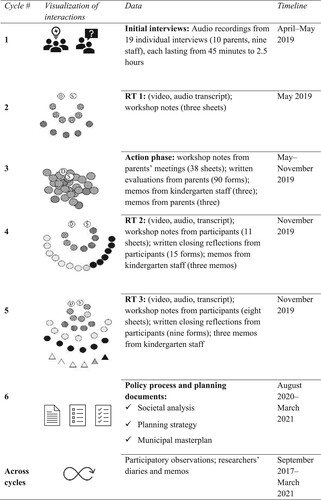

A PAR methodology was chosen as the research design due to the transformative purpose of the study and its emphasis on inclusive democratic deliberation and community empowerment. PAR is described as a ‘social justice methodology that calls for intensive grassroots participation in the pursuit of knowledge democratization and emancipatory social change’ (Keahey, Citation2021, p. 293). The PAR process brought together a wide range of stakeholders to co-design and participate in the research. A snow-balling approach was taken. Citizens (parents) were placed as the central informants, adding on layers of frontline staff, administrative leaders and policy-makers, NGOs and politicians. Taking departure from a social constructionist perspective, the research process has been acknowledged as a dialogical, relational, and future-forming process (Gergen, Citation2015). Deliberative interviews were used as a starting point for the study (Berner-Rodoreda et al., Citation2020), followed by the use of reflecting teams (RT) to facilitate group workshops (Andersen, Citation1987). Three subsequent cycles of RT were used to enable actions and reflections upon adaptive learning and possible policy inputs. In later stages, the PAR process was embedded in mainstream policy-making within the local government, serving as inputs to an ongoing process of revising the municipal masterplan.

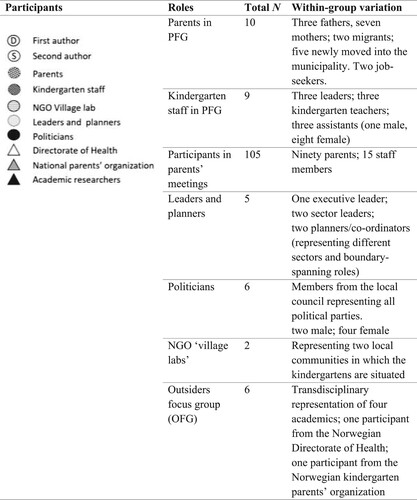

Three kindergartens participated in the study as platforms for exploring co-created policy-making, where parents in the kindergartens and kindergarten staff acted as a critical reference group. A strategic sampling of these actors formed a ‘participant focus group’ (PFG) (Genat, Citation2009). In later stages, a strategic sampling of relevant stakeholders across sectors was undertaken, including policy-makers, boundary-spanning co-ordinators/advisors, administrative leaders, local NGOs and municipal council members. gives an overview of the research participants and their roles.

Figure 1. Overview of the PAR participants (adjusted from Heimburg et al., Citation2021).

A maximum variation strategy was applied to recruit research settings and contributors across the process (parents: socioeconomic status, family structure, ethnicity, gender; kindergartens: private and public, small and large, rural and urban; policy areas and administrative staff and leaders: across sectors; politicians: various political parties; researchers/national policy-makers: across disciplines and sectors). Based on these criteria, the three kindergarten leaders suggested participants among parents/guardians and staff, and executive municipal leaders suggested and forwarded invitations to administrative staff, leaders and politicians. Lists of participants who agreed to be contacted were provided to the first author, followed by an informed consent process. See for an overview of the PAR and data material. A more detailed outline of the procedural process was described in Heimburg et al. (Citation2021).

Figure 2. Overview of the PAR and data material (adjusted from Heimburg et al., Citation2021).

Reflexive thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, Citation2021) was used to analyse the data material via the following iterative steps:

Familiarization with the data.

Coding the data by de-construction.

Generating initial themes by re-constructing the data material.

Reviewing themes.

Defining and naming themes.

Writing up.

Ethical approval to conduct the study was granted by the Norwegian Social Science Data Services (NSD; project number 56952). Written informed consent was obtained after a providing a full description of the study to the participants. Issues of power dynamics are challenging in PAR and co-creation, so the first and second authors actively prepared and engaged with participants to facilitate trust and empowerment.

Results

Four main themes were generated to communicate a thematic storyline. The themes describe key conditions for developing promising policy-making practices by investigating:

The kindergarten as a universal, inclusive and democratic public welfare service.

The facilitation of storytelling and reflection as a catalyst for policy change.

Capacity-building to co-create social inclusion in policy-making.

The process from PAR to plan and policy.

A universal, inclusive and democratic public welfare service

All of our participants acknowledged that kindergartens are unique arenas for nurturing social inclusion by bringing together families from different social backgrounds. All participants urged the importance of mobilizing parents and local communities to engage in co-creation to achieve common goals. They committed to nurture social inclusion and build networks of mutual support to create opportunities for solidarity, tolerance, kindness, empathy and collaboration. In the early stages of the PAR process (stages 1–3), a common vision was developed based on what parents and staff valued and why. These values were voiced through initial deliberative interviews, where the conversations were facilitated to negotiate meaning-making on social inclusion. The proposed vision expressed shared values by parents and kindergarten staff and served to guide co-created actions and socially-inclusive policy-making across the PAR process: ‘We work together to create the childhood conditions we desire, for the benefit of all. Together, we have contributed to all children getting the best possible start in life, and that all children and adults feel seen and recognized as an equal and valuable participant in the local community’ (written material from RTs 1–3).

As the PAR process included more participants (RTs 2 and 3), and while also facilitating conversational invitations to disagree, the initial vision did not change. Rather, all participants were eager to explore how they could move forward together to realize the vision through joint action and strategic policy-making. All participants became change agents in paying this vision forward. They generated learning from new actions that provided valuable input to the ongoing policy process in the municipality. When reflecting on their experiences and roles in co-creation, one parent said: ‘It feels good to be a part of getting things done, and impact on how you would like things to develop in the long run’ (parent, RT 3). Another parent said: ‘I would probably feel unsatisfied about being a passive service recipient. So, I'm glad [the process] provides an open space to give input’ (RT 3).

Parents and kindergarten staff acknowledged that the kindergarten already included a wide range of arenas suitable for participatory processes. For example, as a result of the PAR, parents and kindergarten staff transformed the traditional parents’ meetings from being an arena for transferring information from staff to parents to becoming an arena for collective reflection and the planning of co-created action and, at the same time, an arena for providing input to policy-making processes (see cycle 3, ).

Both parents and staff acknowledged the need for the kindergartens to be the continuous facilitator of active and equitable citizenship as parents come and go. For example, when reflecting on inclusive and active citizenship, one parent said: ‘I think it is important that one gets in place the system around. It is probably the kindergartens that must be the cornerstone here’ (RT 3). Kindergarten staff also acknowledged their roles as carriers of continuity to facilitate empowerment, action, and change. They acknowledged a need for a change in professionals’ mindsets, where the whole life experience of families should serve as their starting point rather than public service and their professional practices.

In general, kindergarten staff expressed a need to reinforce their professional mandate to co-create solutions with parents, children, and local communities. For example, a kindergarten staff member (from RT 3) said: ‘The most important thing is for parents to create a social network, or a community with other parents that will last until the kids almost grow up’. Kindergarten staff members acknowledged that having a strict focus on service production could be a barrier to nurture networks of family support. One of the explanations they gave was that a mindset fixed on what they called ‘the inner life’ of the kindergarten (for example what happens within opening hours and inside the kindergartens’ institutional fences) could make important community assets invisible to the staff (for example wider social networks, meeting-places and local organizations). When reflecting on how a co-creation logic had impacted the mindset of kindergarten staff, one of the staff members said that it had changed the way they thought and shared stories of how this new mindset had affected their practice.

Throughout the PAR process, participants called for a new professional mindset and skills to facilitate co-creation with parents, other sectors, and the wider community. Parents said that the way staff talked about participation and representation had an impact on their motivation to engage and influenced their beliefs about how their participation could have a positive impact. Parents said that they previously had experienced staff downplaying the role of the parents’ representative institutions, for example in RT3 referring to previous parents’ meetings: ‘When asked at one of our meetings to join, it was like “there are almost no meetings, that is, you do not have to do anything, you just have to accept input”’. Parents said they would feel much more motivated to take on such roles if the staff explained the importance of the roles, being explicit as to expectations and recognizing contributions. Based on these experiences, all three kindergartens revised the mandate for their parent/staff co-ordinating committee, and they expanded the number of parents’ representatives on the committee. When reflecting upon this expansion of formal representatives, one parent said: ‘I think it was very positive that there was a representative from each department. You then get a person that you can relate to, that you may know a little better’ (RT 3).

Parents’ representatives also started to pay more attention to actively facilitating the voices of silent and under-represented groups to be heard and acted upon, while the staff members started to empower parents who were living on the margins of social exclusion to take on roles as formal representatives. One parent said that the support and direct request from staff made them believe that they could make a real difference and therefore they volunteered. In addition, they said that being a parent representative opened a variety of social networks and opportunities for their family. As a result of the PAR process, a common municipal committee to gather parents’ democratic representation across kindergartens was initiated. The process contributed to constructing democratic institutions to promote the voices and presence of parents in formal representative systems within the municipality. These new initiatives were built up as arenas resulting from the kindergarten platform.

The facilitation of storytelling and reflection as a catalyst for policy change

Across the PAR process, stakeholders came together to deliberate and engage in meaning-making processes, where they experimented with new formats of engaging in policy-making. In our conversations, it became apparent that stories matter. The multiplicity of stories on lived experiences that participants across roles shared with each other had an impact in terms of making sense of social inclusion as a necessary goal and a process through which to achieve community wellbeing.

The lived experiences of the second author, a parent, shared in the RTs, had an impact on unpacking the potentials for social inclusion in kindergartens and communities. Her story about being included in the kindergarten opened up new social networks and demonstrated potentials for inclusion and citizenship that could begin in the kindergarten setting. The PAR process gave the second author:

… an experience of being valued for [my] life experience and understanding of what it is like to live on the outside of the mainstream society … We all have the same wishes and needs to be understood and heard, regardless of one’s life situation. All competence and lived experiences are relevant and important to make a society work as well as possible for everyone.

During the PAR process, parents and other participants shared similar stories about social inclusion, signalling that the initial story opened for more stories, as well as active and empathetic listening and reflection. Stories of inclusion also triggered stories of exclusion. Participants with a multicultural social background talked about experiences of disconnectedness from community life, and newly arrived citizens told stories about a lack of belonging, of networks and of friends. Some also shared personal stories about financial problems and job loss and how these situations impacted their (family) life (RTs 2 and 3). Across these stories, the participants made each other even more aware and empowered to move forward with a socially-inclusive wellbeing agenda.

The stories we heard raised policy issues beyond the kindergarten setting. Parents expressed concerns about the social exclusion of the proportion of children, and by extension their families and other citizens, who are not enrolled in kindergartens. One parent said: ‘NB: three percent are not in kindergartens. Also, what about those who do not have children? What about those who might move here when the kid is in 4th grade?’ (RT 2). All participants agreed on the necessity to pursue an inclusive vision for the whole municipality and to actively work to avoid situations where the inclusion of some groups results in the exclusion of others. They were generally concerned about raising awareness as a prerequisite for policy change.

When reflecting upon the impact of stories, one of the administrative co-ordinators (from RT 2) asked: ‘How do we get those stories out there so that those who need to know them, and can do something about the problem, actually do something about it?’ Here, participants across roles agreed that active facilitation from employees working in kindergartens and in the wider municipal organization was important. Such ‘coalition building’, grounded in stories and coupled with research-based arguments used to inform the process, created an opportunity space to infuse the further policy-making process with values of social inclusion. For example, one parent said: ‘We talked a lot about starting [policy-making and social change] through raising awareness; keep repeating the knowledge we have on these matters. Continue with these little nudges’ (RT 2).

Participants across roles engaged in multiple meaning-making processes, where the potential for grounding policy processes in the kindergarten platform was deliberated and acted upon. Across the PAR, the participants in general and the parents in particular became important change agents influencing the policy agenda—paying their common vision forward. They said that it was important to start ‘blurring the boundaries between the public sector and the local community’ (administrative staff, RT 2).

Capacity-building to co-create social inclusion in policy-making

Across the PAR process, all participants acknowledged a need for multiple dimensions of capacity-building efforts to co-create social inclusion through policy-making. First, how the processes and dialogues were framed and facilitated had an impact, squarely placing social inclusion and wellbeing for all on the agenda. For example, when facilitating the RTs, the first author actively framed the agenda for the processes by saying things such as the following:

The starting point here is some of our major public health challenges, such as social exclusion, mental health problems, and marginalization and increasing inequity between groups. However, we know that community, belonging, and social support are some of the most important things to promote, as these factors are some of the most important resources for people’s health and wellbeing, regardless of age (RT 2).

Throughout the PAR process, all participants emphasized pursuing a common vision of inclusion that was locally anchored and where policies supported coherence and joint action. For example, one parent said: ‘it is very important to avoid fragmentation. We definitely need to try to nurture co-creation within each sector and facilitate cross-sector thinking’ (RT 2). Across roles, the participants also pointed to a need for a context-sensitive and adaptive implementation of cross-cutting policies in different contexts, allowing for continuous engagement. One parent said: ‘It is important that the structures are flexible, allowing to be shaped by the people who continuously participate in them’ (RT 2). Also, participants across roles talked about the language used in the process, valuing that the dialogues were grounded in an ‘everyday language’ so that: ‘people are able to understand each other’ (RTs 2 and 3).

The participants commonly valued the transformative potentials resulting from using kindergartens as a platform for collaboration. One administrative leader engaged in future-forming explained things this way:

Taking all the resources in the kindergarten into account; parents and employees who not only have social roles as parents and employees, but also take part in community life, organizations and associations [as volunteers and citizens]. If we manage to create a change of attitude through the kindergartens so that it can spread across the world, then we’re about mobilizing a public movement [for social inclusion] (RT 2).

Across the PAR process, all participants highlighted the need for building system and organizational capacity to facilitate collaboration and joint action across policy areas and in the whole of society. In the initial interviews, both the parents and the kindergarten staff said that they had no or very limited experience in participating in local policy-making. According to the staff, the local governance system had little direct impact on the practices in the kindergarten setting, and the existing policies in the municipality were also mostly unknown to the parents. The staff expressed in the initial interviews that national kindergarten regulations, and implementing these, was their main focus. Staff argued that the national framework neglected aspects of engaging parents as a collective or linking kindergartens to local governance. As they experimented with new practices of co-creation to nurture inclusion and wellbeing in the PAR, they became even more attentive to the need for collective forms of co-creation and creating cultures of ‘we’-ness in the kindergartens and the wider community.

Participants across roles stressed the importance of bridging the knowledge and co-ordinated perceptions on public value into mainstream planning processes in the municipality. One of the administrative staff member wrote the following in her closing reflections after RT 2: ‘Important to embed this as a knowledge base for planning processes’ and committing to ‘Bring it forward in my work and planning processes—both the issues focused on here, and the methods used’. One of the administrative leaders wrote in their closing memos after RT 2 that they ‘expected improvements on cross-sectorial co-operation in the whole municipality’. The PAR process provided arguments for organizational capacity-building, incorporating co-creation in a leadership programme for public managers, implementing digital tools for measuring relational co-ordination and capacities, educating staff in process facilitation, and starting to educate and build organizational capacities to adopt a relational approach to welfare co-creation. All these initiatives, in turn, provided learning loops and policy input to the process of revising the municipal masterplan.

Politicians and administrators signalled that they wanted to use the planning processes and the budget to strategically govern towards social inclusion and wellbeing as key public values and use economic and other incentives to support coherence in the municipality’s actions. All participants alike valued a common direction for their work. One of the politicians said that ‘the major directions’ must be agreed upon (RT 2). Another administrative co-ordinator said: ‘I, too, get this inner drive when I feel that we are working in the same direction, and I think that what comes up here gives me even greater hopes that we can go on in the same direction’ (RT 3), suggesting that a common vision had an impact on motivation, passion and purpose in their job. Participants across roles supported this need to move forward together in the same direction and to work coherently and systematically to achieve the desired future.

All of the participants appreciated the PAR process and the use of RT as an approach to nurture transformative action and deepen communicative capacity-building. One parent said, ‘I believe that this is a methodology that can create movements, getting many actors on board’ (RT 2). The communicative approach used was appreciated by participants. Summing up from a group workshop in RT 3, one of the parents said: ‘we have appreciated trying this form of conversation [reflective team]. The politician says that he feels liberated from going on with an agenda, and rather just be open to listening and to receive input’. One of the parents with lived experiences of marginalization expressed their experiences of participating in the process:

We have thrown ideas back and forth and I [have] experienced being heard and … given space to have a voice. For me, it is incredibly important that this is connected directly to the politicians. For me, this is a different experience of Norway as a democracy … silent voices become powerful when they’re combined.

Across the capacity-building elements presented in this theme, a key issue was to enable stakeholders to effectively co-ordinate their work across boundaries through cross-cutting structures, upskilling and the active facilitation of spaces and places for informal and formal representation in co-creation.

The process from PAR to plan and policy

In the final stages of the PAR process, the first author worked alongside stakeholders in the municipality to adopt knowledge and input from the PAR in the ongoing policy process of revising the municipal masterplan. Throughout the process, a focus on the citizens as the central actors was maintained and advocated. This focus legitimized negotiation on public values based on relational ethics and what the public valued through the ongoing conversations between all stakeholders involved in the process. Initially, the planning process was designed to revise eight sector plans parallel to the masterplan (for example childhood and education, health and care, culture and arts, business development, spatial planning). Supported by arguments from the PAR, the working group of local policy entrepreneurs decided to merge all partial plans into one coherent plan for the municipality, where the whole life experience of the citizens became the common focus. Both indirect input from the PAR (knowledge accumulation from relevant theory and research) and direct input from the PAR participants was used to inform the policy process and the planning strategy.

In the final proposal for the municipal masterplan, visible traces from policy input and the negotiated values from the PAR were made explicit in the policy document. Quotations from the PAR process, such as ‘mutual trust, respect, and dialogue. Then, we have a [basis] for talking about co-creation’ (from a politician) and ‘Being recognized as a resource does something with the truths you carry in you about yourself’ (from a parent), were used in the masterplan to set the agenda and to visualize key values and strategies.

Aligned with the PAR process, the masterplan was framed through the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and human rights agendas. The societal goals, expressing key public values, broadly echoed the initial vision that was developed and adopted by parents and stakeholders alike across the PAR. The masterplan was therefore developed through co-creation, where the kindergarten platform played an important role in promoting socially-inclusive participation in the planning process. The final plan described societal objectives reflecting key public values under the heading ‘This is what we want’, accompanied by strategies described as ‘This is what we’re going to do’. The final plan included key indicators to reflect ‘This is what we will measure’, which focused on wellbeing, social inclusion and equitable outcomes. The masterplan provided an accountability system, serving as a feedback loop to the public, staff, administration, politicians and other stakeholders in the municipality. The goals, strategies and accountability system outlined in the plan served as a strategic management tool to mobilize joint action and to keep the conversation going on important public values. The masterplan was adopted (by consensus) of the municipal council in May 2021.

Discussion

This article has shown that kindergartens are promising and valuable platforms for transforming personal experiences of dis/value co-created at the micro level into public policy.

Children and their environment are common concerns embedded in the kindergarten platform, which makes social inclusion and wellbeing for all a value of interest. Parents were motivated to participate in co-creation both for their own needs and their visions of an ideal future. Particularly, parents in politically- and socially-marginalized situations expressed that they felt valued in the process and that they had had an impact. Our discussion therefore focuses on three aspects of social inclusion that are vital for generative deliberation on dis/value and for placing wellbeing for all at the heart of public values: access, agency and participation.

Access

First, the Norwegian approach to universal access to welfare and kindergartens facilitated socially-inclusive participation mobilized from the platform. Kindergartens bring citizens across social divides together creating ideal arenas to share experiences of dis/value. Kindergartens are welfare institutions that are often situated close to home for families. This makes kindergartens open and inducive to inclusive public participation and co-creation. Such a place-based orientation has previously been supported by Lightbody and Escobar (Citation2021) to facilitate equality in community engagement, where the kindergarten platform seems to act as anchor institutions to support social change for the common good. In this case, kindergartens increased both the informal and formal participation and representation of parents in general, and marginalized parents in particular. Participants were able to access and have a voice in a policy process (Young, Citation2000), and thereby take part in transforming experiences of dis/value into ambitions for creating public value set out in formal plans.

Agency

Second, parents and key stakeholders in the PAR said they felt empowered in terms of agency through the platform. By embracing the life experience of citizens and their social worlds, kindergartens can act as agenda-setters for making social inclusion a common public value across sectors and in the wider society. In our kindergartens, parents engaged with each other in ways that supported inclusion. The kindergarten platform seems to empower agency among citizens (parents), and especially among those who often are considered ‘hard to reach’ but can be ‘easy to ignore’ in policy-making (Lightbody & Escobar, Citation2021). By connecting PAR to planning and policy-making, the process invited meaning-making and negotiation between individual (experienced) dis/value and formally adopted public values through planning. The results therefore show how a parent’s legal right to participate can be facilitated in practice—reframing their role from passive consumers of welfare into active co-creators of public value.

Our results support the arguments made by Young (Citation2000) and Bartels et al. (Citation2020) about focusing on the quality of relationships and on communication in the policy-making process. The PAR provided an opportunity to disrupt power imbalances and dominant discourses in negating dis/value. Participants could talk and reflect without being interrupted; commonly-agreed ‘rules’ were set out for inclusion in the conversations, providing rituals for greeting, storytelling and recognition, as previously suggested by Young (Citation2000). Based on our study, we suggest that kindergartens enable an inclusive wellbeing agenda. This agenda motivated all PAR participants to be involved in our study. However, an inclusive imperative might be even more valuable for marginalized parents and families due to proportional benefits, thereby giving support to understanding public value as an heterogenous assemblage (Cluley et al., Citation2020).

Participation

Finally, our results suggest that participatory parity and relationships between core stakeholders are keys for transformative policy change. Inclusive participation generated from the kindergarten platform seems to be enabled by empowerment and active facilitation, policy entrepreneurship, boundary-spanning endeavours and cross-cutting structures. These elements for systemic change were previously reported by Bolton et al. (Citation2021). Our promising results with kindergartens being used as collaborative platforms might facilitate redistribution, recognition and representation to achieve participatory parity, as requested by Fraser (Citation2009). However, our results also provide arguments for people to experience ‘mattering’ in general and in particular for those most impacted by disparities. Wellness and fairness can be improved by nurturing and co-ordinating human relationships (Bartels et al., Citation2020; Gergen et al., Citation2001; Heimburg & Ness, Citation2020). Acknowledging interdependency between people seems to be vital to make positive and transformative systems change (Bolton et al., Citation2021), and enable generative and empathetic deliberations on dis/value. Our study suggests that access to platforms and using agency through platforms to impact public policy are key issues in terms of making people matter.

Our study provides promising results, yet there are still important limitations to be reported. PAR participants might feel obliged to satisfy the wishes of the researcher and process facilitator, which might skew dialogues on dis/value. This problem was minimized by using reflective teams and commonly-agreed ‘rules’ for inclusion and active listening in the conversations. Although the planning process included more stakeholder involvement than presented in this article, the PAR was initially grounded in only three kindergartens and thus representing approximately 15% of the eligible population of children between one and five years of age and their families. Thereby, the majority of citizens within the municipality was not directly involved in the PAR. In addition, departing from this platform runs the risk of ignoring the 3% of families in Norway who do not take advantage of their legal right to a kindergarten. These families are vital voices in negotiating dis/value as they might represent groups most impacted by disparities; an important concern that also was noted by the PAR participants. These concerns are consistent with perceptions of public dis/value as being shaped by individuals who act as normative stakeholders of specific institutions and its ingroup bias (Portulhak & Pacheco, Citationin press). Moreover, our study represents one local government in a specific national setting. Other countries and communities might have better platforms for the purposes explored in the present study as co-creation is highly context dependent (Loeffler & Bovaird, Citation2020). Possible examples of platforms to be further explored might be schools, healthcare institutions, community centres, libraries and churches. However, we suggest that platforms should be chosen according to their potentials for social inclusion.

Concluding reflections

Based on our study, we support Fung’s (Citation2015) suggestions for putting the ‘public’ back in public governance and thereby earning popular support for normative public values based on social justice and wellbeing for all. The presented study provides arguments for addressing an ecology between dis/value as lived experience, as well as for advocating and legitimizing public values through place-based policy-making by using suitable platforms. Such an approach can support accountability for equitable public value outcomes through governance. Supporting capabilities to penetrate walls of exclusion through co-created policy-making leads to experiences of dis/value being shared and to transformative systems change.

Our study has practical implications in terms of integrating welfare institutions with relational co-ordination in planning and community development. We recommend that managers search for platforms that are universal and open for public participation with the potential for connecting processes to formal planning and governance. Platforms should support socially-inclusive access and agency, and adopt a relational approach to transforming socio-political institutions. In our experience, PAR is a suitable method to support inclusive participation and ‘mattering’. However, based on the complexity of the issues involved, we propose that future research should explore pathways that will intersect dis/value and public value governance within a variety of platforms and by using a wide range of methodology.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all of the participants and local stakeholders who co-created this study. We are also grateful to Borgunn Ytterhus, Ottar Ness and Public Money & Management’s reviewers for feedback on earlier versions of the manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Andersen, T. (1987). The reflecting team: Dialogue and meta-dialogue in clinical work. Family Process, 26(4), 415–428. DOI: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.1987.00415.x

- Ansell, C., & Gash, A. (2018). Collaborative platforms as a governance strategy. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 28(1), 16–32.

- Ansell, C., & Torfing, J. (2021). Public governance as co-creation: a strategy for revitalizing the public sector and rejuvenating democracy. Cambridge University Press.

- Bartels, K. P. R., Wagenaar, H., & Li, Y. (2020). Introduction: Towards deliberative policy analysis 2.0. Policy Studies, 41(4), 295–306.

- Berner-Rodoreda, A., Bärnighausen, T., Kennedy, C., Brinkmann, S., Sarker, M., Wikler, D., … McMahon, S. A. (2020). From doxastic to epistemic: A typology and critique of qualitative interview styles. Qualitative Inquiry, 26(3-4), 291–305.

- Bolton, R., Logan, C., & Gittell, J. H. (2021). Revisiting relational co-ordination: A systematic review. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, https://doi.org/10.1177/0021886321991597

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2021). One size fits all? What counts as quality practice in (reflexive) thematic analysis? Qualitative Research in Psychology, 18(3), 328–352. DOI: 10.1080/14780887.2020.1769238

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Harvard University Press.

- Cluley, V., Parker, S., & Radnor, Z. (2020). New development: Expanding public service value to include dis/value. Public Money & Management, DOI: 10.1080/09540962.2020.1737392

- Fraser, N. (2009). Scales of justice. reimagining political space in a globalizing world. Columbia University Press.

- Fung, A. (2015). Putting the public back into governance: The challenges of citizen participation and its future. Public Administration Review, 75(4), 513–522.

- Genat, B. (2009). Building emergent situated knowledges in participatory action research. Action Research, 7(1), 101–115.

- Gergen, K. J. (2015). From mirroring to world-making: Research as future forming. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour, 45(3), 287–310.

- Gergen, K. J., McNamee, S., & Barrett, F. J. (2001). Toward transformative dialogue. International Journal of Public Administration, 24(7-8), 679–707.

- Hartley, J., Parker, S., & Beashel, J. (2019). Leading and recognizing public value. Public Administration, 7(2), 264–278.

- Haug, K. H., & Storø, J. (2013). Kindergarten—a universal right for children in Norway. International Journal of Child Care and Education Policy, 7(2), 1–13.

- Heimburg, D. v., & Cluley, V. (2020). Advancing complexity-informed health promotion: A scoping review to link health promotion and co-creation. Health Promotion International, DOI:10.1093/heapro/daaa063

- Heimburg, D. v., Langås, S. V., & Ytterhus, B. (2021). Feeling valued and adding value: A participatory action research project on co-creating practices of social inclusion in kindergartens and communities. Frontiers in Public Health, DOI:10.3389/fpubh.2021.604796

- Heimburg, D. v., & Ness, O. (2020). Relational welfare: A socially just response to co-creating health and wellbeing for all. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, DOI: 10.1177/1403494820970815

- Keahey, J. (2021). Sustainable development and participatory action research: A systematic review. Systemic Practice and Action Research, 34, 291–306.

- Kenney, M., & Zysman, J. (2015). Choosing a future in the platform economy: the implications and consequences of digital platforms. Paper presentation at the Kauffman Foundation New Entrepreneurial Growth Conference.

- Lightbody, R., & Escobar, O. (2021). Equality in community engagement: A scoping review of evidence from research and practice in Scotland. Scottish Affairs, 30(3), 355–380.

- Loeffler, E., & Bovaird, T. (eds.). (2020). The Palgrave handbook of co-production of public services and outcomes. Springer.

- Lundin, R. A., & Söderholm, A. (1995). A theory of the temporary organization. Scandinavian Journal of Management, 11(4), 437–455.

- Ongaro, E., Sancino, A., Pluchinotta, I., Williams, H., Kitchener, M., & Ferlie, E. (2021). Strategic management as an enabler of co-creation in public services. Policy & Politics, 49(2), 287–304.

- Pedersen, A. W., & Kuhnle, S. (2017). The Nordic welfare model. In O. Knutsen (Ed.), The Nordic models in political science. Challenged, but still viable? Fagbokforlaget.

- Portulhak, H., & Pacheco, V. (in press). Public value is in the eye of the beholder: Stakeholder theory and ingroup bias. Public Money & Management.

- Prilleltensky, I. (2020). Mattering at the intersection of psychology, philosophy, and politics. American Journal of Community Psychology, 65(1-2), 16–34.

- Sen, A. (2005). Human rights and capabilities. Journal of Human Development, 6(2), 151–166.

- Sørensen, E., & Torfing, J. (2009). Making governance networks effective and democratic through metagovernance. Public Administration, 87(2), 234–258.

- Statistics Norway. (2020). Kindergarten statistics. https://www.ssb.no/en/utdanning/statistikker/barnehager.

- Strokosch, K., & Osborne, S. P. (2020). Co-experience, co-production and co-governance: An ecosystem approach to the analysis of value creation. Policy & Politics, 48(3), 425–442.

- Trætteberg, H. S., & Fladmoe, A. (2020). Quality differences of public, for-profit and nonprofit providers in Scandinavian Welfare? User satisfaction in kindergartens. Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 31(1), 153–167.

- UN. (2016). Identifying social inclusion and exclusion. Report on the world social situation 2016. https://www.un-ilibrary.org/content/books/9789210577106c006.

- Vamstad, J. (2012). Co-production and service quality: The case of co-operative childcare in Sweden. Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 23(4), 1173–1188.

- Young, I. M. (2000). Inclusion and democracy. Oxford University Press.