IMPACT

This article will be useful to policy-makers and public sector managers in terms of understanding how public audit regulation affects audit practitioners in determining applicable audit standards. Over 70% of chartered public finance auditors in Finland were found to voluntarily adopt the International Standards on Auditing (ISA) despite a regulatory environment where the ISA were not strictly required in local government audits.

ABSTRACT

A growing literature has identified several factors differentiating public and private sector auditing, which might advocate differences in audit regulation between these sectors. This article contributes to the existing literature by examining the voluntary adoption of International Standards on Auditing (ISA) in local government audits. The empirical data in this article is based on a survey of all Finnish authorized public sector auditors. The results show that voluntary adoption of ISA in local government audits is increasing, which can be explained using the institutional theory of influencing forces.

Introduction

This article investigates the voluntary adoption of private sector driven audit standards by privately-owned audit companies in local government audits. In prior academic literature, local public audit has been highlighted as under-researched (Hay & Cordery, Citation2018). Previous studies have stressed the importance of audit standards in securing high-quality auditing in public and private sector audits (Francis, Citation2004; Knechel et al., Citation2013). The literature examining voluntary adoption of the International Standards on Auditing (ISA) is scarce (Boolaky & Soobaroyen, Citation2017). The wide variation in the depth of implementing the ISA internationally and nationally in local public audits underpins the importance of the theme.

Compliance with audit standards is generally considered to be a crucial factor in securing high-quality audits, at the same time there is a strengthening discussion on the need for own audit standards of less complex entities (IAASB, Citation2022) as the increasing complexity of larger private sector enterprises needs to be addressed in the ISA. Furthermore, similar challenges can be identified in implementing the almost entirely private sector driven ISA in public sector audits, such as local governments audits. Despite the ISA presenting a public sector perspective on the applicability of the standards to the audit of the financial statements of public sector entities, the heritage of these standards poses a threat to implementation in public sector audits.

This article contributes to the academic and professional discussion by providing new insights into the applicability of the ISA in local government audits by surveying chartered public finance auditors’ experiences of the voluntary adoption of the ISA in a regulatory environment where ISA adoption is not obligatory. Our research was targeted at local government statutory auditing in a unitary state with 310 municipalities. The established way of doing municipal auditing, based on national standards, was challenged after 2012 with the ISA (Julkishallinnon ja -talouden tilintarkastajat ry, Citation2012). Our empirical study shows that the voluntary adoption of the ISA in local government audits has gained momentum. This can be explained using institutional theory of three influencing forces.

The setting: local government audit system, regulation and the market in Finland

Manes Rossi et al. (Citation2021) classified European local government external audit systems into private, mixed and public systems. In this classification, Finland belongs to the group of private audit systems. In Finland, local government audit is carried out by independent professional auditors that, in addition to the general auditing education and certification, have taken a specialized public sector audit certification (Manes Rossi et al., Citation2021). According to Johnsen et al. (Citation2004), the entire Finnish municipal audit system can be characterized as ‘plural forms’, because the Finnish system of municipal auditing consists of professional auditing executed by private professional audit firms and municipal audit committees manned by politicians responsible for performance auditing.

Finnish municipalities have traditionally been self-governing local units responsible for the provision of educational, social, cultural and healthcare services to their inhabitants (Citation1995). Finnish local government auditing is regulated by two Local Government Acts (365/1995 and Citation2015) and the Act on Chartered Public Finance Auditors (1142/2015). Citation2015) specifies that the auditors of municipalities in Finland must be Certified Public Finance Auditors (CPFAs) or audit firms authorized by the Board of Chartered Public Finance Auditing (BCPFA). The Act on Chartered Public Finance Auditors (1142/2015) states that, in carrying out an audit assignment, auditors and auditing corporations should follow the good chartered public finance auditing practice recommendation (Suomen Tilintarkastajat ry, Citation2020). The fundamentals of the guidelines for good auditing practices in public administration are based on the ISA issued by the International Federation of Accountants (IFAC). The basis of the Finnish public audit guidance increases the comparability of the setting of this study to other public audit settings internationally.

The recommendation on good chartered public finance auditing practice was published by the Finnish auditors’ association (Suomen Tilintarkastajat ry). It specifies that ISA, national private sector auditing standards or the ISSAIs are not obligatory in public sector audits. Note that the International Standards of Supreme Audit Institutions (ISSAI), issued by International Organisation of Supreme Audit Institutions (INTOSAI), are based on the ISA. However, the good chartered public finance auditing practice recommendation, rather ambiguously, states that the ISA can be adopted as complementary guidance in public sector audits where applicable. This ambiguity was highlighted by a 2019 legal judgment, where the court of appeals stated that the ISA is not an obligatory regulation in public sector audits in Finland (Vaasa Court of Appeals, Citation2019). The judgment added that the ISA can be taken into account as additional guidance for good chartered public finance auditing practice. However, the depth of the voluntary adoption of the ISA is unclear. The relevant differences and similarities between the good chartered public finance auditing practice recommendation and the ISA are presented in , which shows that the main contents of the ISA are included in the local recommendation, but only at the principles level. On the other hand, ISA does not recognize certain specific areas of municipal auditing such as administration and central government transfers.

Table 1. Differences between the good chartered public finance auditing practice recommendation and the ISA.

The Finnish Local Government Act states that CPFAs must audit the administration, accounting, and financial statements of municipal organizations for the respective accounting period, in accordance with good auditing practices. Furthermore, CPFAs are required to ascertain that:

The administration of the municipality has been structured in accordance with the law and the decisions of the local council.

The municipality’s financial statements and consolidated financial statements have been prepared in accordance with the provisions concerning the preparation of financial statements and provide accurate and sufficient information on activities, finances, financial trends, and financial obligations.

The information on the basis for and use of central government transfers to local government is correct.

The internal controls for the municipality, the local authority corporation, and the oversight of the local authority corporation have been appropriately organized.

Competition in the Finnish local government audit market is strict when it comes to the pricing of statutory audits. Prior literature indicates that, in the Finnish municipal audit market, price is the main decisive factor for winning local government audit engagements (Johnsen et al., Citation2004; Vakkuri et al., Citation2006; Oulasvirta et al., Citation2021). In fact, the Swedish experience also shows that, when municipalities procure audit services in the open market, price will, in most cases, be the determining factor (Tagesson et al., Citation2015). This is particularly so when there are only a few tenders. Tagesson et al. (Citation2015) found out that Swedish municipalities often awarded their professional auditing contract to the firm that offered the lowest price. Low prices probably lead to tight time schedules and lower-priced auditors (less experienced auditors or trainees, rather than senior auditors) in order to save costs. Furthermore, time constraints on auditing create a risk to audit quality (Halim et al., Citation2014; Broberg et al., Citation2017; Coram et al., Citation2003). These circumstances can be assumed to lead Finnish municipal auditing to stick to Finnish sound public audit practice rules, rather than voluntarily working to the detailed and demanding ISA. When audit markets function with low prices, audit firms try to save costs and time in executing their municipal audit engagements (Johnsen et al., Citation2004; Vakkuri et al., Citation2006; Oulasvirta et al., Citation2021). If audit firms voluntarily strictly followed the ISA, and prepared all their documentation perfectly according to the ISA, the possibility for profitable business would probably diminish. Supplementary non-audit services offered by audit firms to their municipal audit clients might benefit the municipalities and, on the other hand, support audit evidence gathering, but at the same time they create a risk to audit independence and objectivity (Stewart, Citation2006; Tepalagul & Lin, Citation2015).

In the Finnish context, tight competition and low prices pressure audit firms, in order to be profitable, to reduce the audit time reserved for the municipal audit engagement (Johnsen et al., Citation2004; Oulasvirta et al., Citation2021; Vakkuri et al., Citation2006). Existing literature (Johnsen et al., Citation2004) suggests that, in recent years, there has been a keen interest by private audit firms in entering the Finnish municipal audit market. Furthermore, Johnsen et al. (Citation2004) suggested that competition may affect the content of an audit. Vakkuri et al. (Citation2006) raised the question of possible impacts on the competitive situation of the audit markets, such as lowballing and opinion shopping. Recent studies show that the municipal audit market and competitive tendering is still leading to low prices against the lowballing hypothesis, in which prices increase after the initial creation of new audit markets (Oulasvirta et al., Citation2021). The phenomenon of low prices is a risk in terms of audit quality (Stewart, Citation2006; DeAngelo, Citation1981). Thus, tight competition and low prices could create a pressure to stick to the more loose Finnish sound auditing practice rules, rather than switching to the more demanding and detailed ISA. Furthermore, Finnish audit firms try to compensate for the lower revenue streams from the statutory municipal audit engagements by selling supplementary services to municipal audit clients (Oulasvirta et al., Citation2021). This could be a factor that means that even the more demanding and detailed audit standards such as the ISA could be voluntarily adopted even if it means lower profitability in the statutory municipal audit service. A third possible factor affecting municipal auditors’ willingness to follow Finnish sound auditing practice rules as well the ISA is the strengthening quality oversight of the municipal audit quality of the Finnish Oversight Function in the Finnish Patent and Registration Office of the Ministry of Trade.

The role of auditing in the public sector

Recent literature reviews of public sector auditing have highlighted the importance of public sector auditing and its practices (Bisogno et al., Citation2022; Degeling et al., Citation1996; Hay & Cordery, Citation2018; Lapsley & Miller, Citation2019; Mattei et al., Citation2021). Although there is a growing literature that explores public sector auditing, it is a comparatively unexplored research field where several research gaps can be identified (Mattei et al., Citation2021). One of these unexplored research streams identified are international standardization and harmonization trends in public sector auditing (Bisogno et al., Citation2022; Mattei et al., Citation2021).

Starting from the 1980s and 1990s, and the advent of the new public management (NPM) philosophy, public sector auditing has been transforming closer to corporate auditing (Hay & Cordery, Citation2018; Manes Rossi et al., Citation2021; Mattei et al., Citation2021). After NPM introduced accrual accounting, auditing practices in the public sector started to focus more on standards and formal annual financial statements (Manes Rossi et al., Citation2021). In terms of standards, the ISA started to gain momentum in public sector auditing.

Although there are many advantages to be gained by public sector auditing standardization and harmonization across nations, this topic has received little research attention (Manes Rossi et al., Citation2021). A literature review by Mattei et al. (Citation2021) shows that academic research interest in public sector auditing has grown and become more diverse. However, the subtopic of public sector audit standardization has not received sufficient research attention (Bisogno et al., Citation2022; Manes Rossi et al., Citation2021). This article helps fill this research gap by examining the voluntary adoption of private sector driven audit standards in local government audits. Mattei et al. (Citation2021) suggested in their literature review that future studies could use institutional theories to analyse the pressures on public sector auditors. We adopted the analytical lenses of institutional theory in our case study as an explanatory framework for the extent of auditors’ willingness to adopt international audit standards (ISA).

Institutional theory as an explanatory point of departure

Institutional theory is a good foundation for understanding differences in European accounting institutions (Brusca et al., Citation2015) and explaining how different factors and pressures (DiMaggio & Powell, Citation1983) influence accounting choices and practices (Christiaens et al., Citation2015; Collin et al., Citation2009; Dacin & Dacin, Citation2008; Manes Rossi et al., Citation2016; Oulasvirta, Citation2014). Furthermore, auditing choices and practices can be analysed using the same institutional theoretical framework. The existing literature suggests that institutional factors have a significant impact on ISA adoption in auditing (Boolaky & Soobaroyen, Citation2017). Our study built on the institutional approach to explain the adoption of the ISA in public sector auditing, which is a less represented theme in accounting literature than the adoption of IPSAS standards in public sector accounting. That local government auditors’ adherence to the ISA is voluntary in Finland provides a useful opportunity to investigate the impact of different institutional forces (mimetic, coercive and normative). We were also able to compare institutional forces in auditing to the corresponding forces in government accounting choices in Finland. The most important influencing factor in governmental financial accounting choices has been the public sector accounting tradition, which has resisted pressures to change the established accounting institution (Oulasvirta, Citation2014). An important question in our research is whether the mainly private sector driven international audit standards could have a changing impact on the regulation and practice of municipal auditing, or are we looking at an established audit practice that resists change pressures (as was the case with IPSAS standards)?

Vakkuri et al. (Citation2006) highlighted the complex characteristics of the Finnish municipal auditing functioning in a context of institutional evolution where ‘markets’, ‘hierarchies’ and ‘mixed governances’ are displayed. Although the audit market has been forced into a new competitive environment, institutional and regulatory change in municipal auditing involves also path dependences, locked-in structures of practices and systems that cannot be easily changed (Vakkuri et al., Citation2006). The maintenance of the audit institution ‘as it is’ is less burdensome for auditors compared to new rules of the game (DiMaggio & Powell, Citation1991, pp. 30-31). Furthermore, audit quality is typically non-transparent for the audit client, and this may contribute to auditors’ reluctance to accept more strict audit standards that leave less room for judgment and require the use of formal, heavy documentation procedures. The ISA leaves also less possibilities for audit firms to manipulate their quality control.

In their widely-used framework, DiMaggio and Powell (Citation1983) identified three mechanisms that may lead to institutional isomorphism. In the context of our study, this may mean a convergence of audit practices in Finnish audit organizations. These three forces are coercive, normative and mimetic forces. Coercive isomorphism may be a result of legal acts and rules compelling organizations to adopt the same kinds of structures and processes. An example of a source of coercive isomorphism is a supranational regulator like the European Union (EU). The EU has the right to pass a directive ordering its member states to adopt, for example, international standards on auditing (ISA) but, so far, it has not done this. On the other hand, a strong political interest in audit standardization at the national level could lead to voluntary national legislative reforms, acts and statutes requiring the ISA in audit practice.

Mimetic isomorphism is when an organization is trying to adopt the best course of action by following similar organizations that they perceive to be successful and legitimate (DiMaggio & Powell, Citation1983). If the ISA is successfully implemented in other Finnish organizations, or in municipal organizations in other countries that could be considered as benchmarks in the field of municipal auditing, this could have an important impact, leading to a change in the auditing methodology in the Finnish municipal audit market. The potential impact of implementing the ISA in municipal audits could be strengthened from an audit quality perspective if the ISA rules in the municipal auditing context are convincing and if there are serious deficiencies in the current municipal auditing model. The dominance of a few big audit firms in the municipal auditing may also lead to the growth of institutional converging forces. The dominant firms are part of international chains serving both private and public sector audit clients, and there could be a mimetic factor transferring sound audit practice rules more or less from business sector auditing to municipal sector auditing. The earlier discussions of mimetic isomorphism, modeling and uncertainty by DiMaggio and Powell (Citation1983, p. 154) point out, that ‘the more uncertain the relationship between means and ends the greater the extent to which an organization will model itself after organizations it perceives to be successful’. Furthermore, DiMaggio and Powell (Citation1983, p. 155) also suggested that ‘the more ambiguous the goals of an organization, the greater the extent to which the organization will model itself after organizations that it perceives to be successful’. These uncertainties and ambiguities might be one way to explain the behaviour of audit firms as ‘reliance on established, legitimated procedures enhances organizational legitimacy and survival characteristics’ (DiMaggio & Powell, Citation1983, p. 155).

Normative isomorphism is associated with professionals and other stakeholders imposing pressure on organizations and their structures and processes. Regarding our study, normative forces represented by the auditing and accounting profession and its associations are especially important. Organizational innovations like the ISA are much more likely to have an influence when they are supported by national or global professional associations (Carpenter & Feroz, Citation2001, p. 570). However, if the auditing and accounting tradition is deeply rooted, mimetic or new normative forces have difficulty changing the tradition (Dacin & Dacin, Citation2008). Our assumption, based on institutional theoretical lenses, is that the mimetic and normative forces to adapt to the ISA in municipal auditing have gained momentum in Finland. This is down to the regulatory policy line of the Finnish Audit Oversight Board. In addition, drawing from Deegan (Citation2001, pp. 272–273), coercive isomorphism can be supported by the managerial branch of stakeholder theory as audit practitioners might be satisfying the demands of powerful stakeholders when voluntarily adopting the ISA. Auditor oversight might support audit practitioners complying with the ISA as this could make audit quality assessment more straightforward and simpler. From the perspective of the managerial branch of stakeholder theory, in addition to auditor oversight, there could be other powerful stakeholders driving ISA use (Mitchell et al., Citation1997). In our case, the audit firms’ potential powerful stakeholders could also include audit clients, investors, financers and audit firm employees. As audit firms serve both public and private sector clients, the potential demands of private sector clients, such as publicly-listed firms, might affect the methodology implemented in all audit engagements, including local government audits. Local government managers responsible for the preparation of financial statements might be less keen on changing from the Finnish sound public sector auditing practice to the more detailed and less public sector oriented ISA. Voluntary implementation of the ISA might create an additional burden on the preparers of financial statements, who would have to learn how to avoid an ISA-based qualified audit opinion.

Data and methods

We sent a survey to all active CPFAs in Finland and conducted interviews with auditors working in six audit firms that were dominating the Finnish audit market, as well as with the representatives of the Finnish Audit Oversight Function in the Finnish Patent and Registration Office. The survey was sent via email in the second half of 2020 and the answers were received between July 2020 and September 2021. The survey was also targeted at chief financial officers in municipalities and to chairs of municipal audit boards (which consist of elected members), but in this article we are only using the CPFAs’ responses.

The interviews were conducted between August 2021 and November 2021. In this article, we use the interviews conducted with eight leading auditors at the five biggest Finnish audit firms (BDO, Deloitte, EY, KPMG and PwC—in alphabetical order). These interviews were tape-recorded and transcribed and lasted from 30 minutes to one hour.

The register of active CPFAs was supplied by the Finnish Patent and Registration Office. The questionnaire was sent to 110 active CPFAs in Finland and 43 of them returned a completed questionnaire. The returned questionnaires represent Finnish CPFAs comprehensively, as these auditors work both for Big 5 companies and smaller audit firms. Furthermore, the returned questionnaires represent nearly half of the active Finnish CPFAs who are auditing Finnish municipalities. There were 309 municipalities in Finland in 2021 (Association of Finnish Local and Regional Authorities, Citation2022).

The questions we analyse here were:

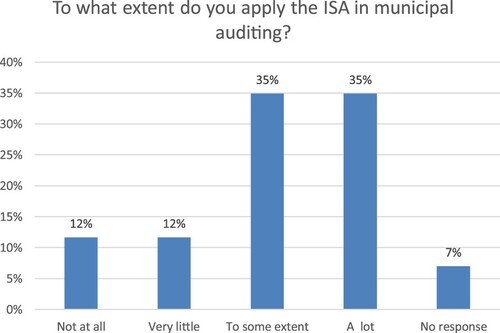

‘To what extent do you apply ISA standards in municipal auditing?’ With this question we were looking for the level of voluntary adoption of the ISA in municipal audits. We received 43 responses to this question.

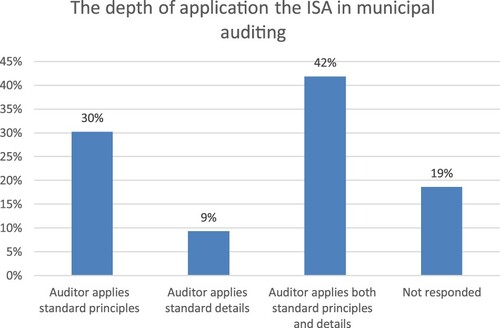

‘If you use the ISA standards how do you use them? I am using both principles and details, I am using only principles, I am using details’. With this question wanted to understand the depth of the voluntary adoption of the ISA, as this has been a black box in municipal auditing. We received 35 responses to the second question.

‘If you apply the principles of ISA in municipal audits, how do you see them as a source for good chartered public finance auditing practice?’ This was an open question. With this question we wanted to examine the methods of applying strongly private sector driven audit standards in public sector audits. We received 22 responses to the third question.

‘Do you think that the current regulation of good chartered public finance auditing practice in Finland is ambiguous (yes/no)?’ The question was constructed to gain evidence of the level of ambiguity related to the current guidance on good public sector auditing practice. We received 43 responses to the fourth question.

Our fifth question was aimed at those who answered yes to the fourth question. The question was ‘How would you clarify the good chartered public finance auditing practice in order to mitigate or remove the ambiguousness?’ We received 15 responses. Through the answers to our fifth question, we created an overview of potential development targets in public sector audit guidance from the perspectives of practising auditors. Altogether, 15 auditors responded to this question.

Results

presents the results for the first question. The results show that a majority (70%) of Finnish CPFAs apply the ISA on a voluntary basis to some extent or a lot in auditing municipalities: 35% of the auditors applied the ISA on voluntary basis a lot and 35% to some extent. Only 24% of auditors applied the ISA very little or not at all, and 7% of auditors gave no response to this question.

provides the results for the second question, which was presented to CPFAs who answered the first question saying they use the ISA a lot or to some extent. This second question was answered by 35 CPFAs; 18 (42%) answered that they apply both the principles and details of the ISA, 13 (30%) answered that they apply only ISA principles, and four (9%) said that they apply details of the ISA. The results show clear dispersion in the depth to which auditors use the ISA in municipal audits. The heterogeneity of the extent of applying the ISA is likely to increase the lack of unity in Finnish municipal auditing in this respect.

Those respondents who answered that they apply the ISA on the principles level were asked what they understand about the principles of the ISA as a source for good chartered public finance auditing practice. This question was answered by 22 respondents; 17 said that they complement the good chartered public finance auditing practice with the ISA standards. The main reason given was the limited regulation of good chartered public finance auditing practice. Respondents thought that more specific public sector audit guidance was necessary regarding, for instance, the auditing of central government transfers to local government and municipal administration matters, which are specifically stipulated to be included in municipal auditing by the Citation2015). Two auditors answered that they applied the ISA because of audit quality requirements set by the Finnish Audit Oversight Board in the Finnish Patent and Registration Office. One auditor said that the ISA defines sound audit practice and that public sector auditors should not be exempt from this in their auditing.

The next question was related to how clear respondents considered the good chartered public finance auditing practice to be; 60% of the respondents were of the opinion that good auditing practices in public administration have been defined reasonably accurately. On the other hand, 40% of respondents answered that there is inaccuracy or vagueness in the way the Finnish good auditing practices in the public sector have been defined. In light of our survey and interviews, it seems that the content of the current good chartered public finance auditing practice recommendation needs to be clarified in relation to the ISA. Those who criticized the good chartered public finance auditing practice considered the guidance too loose, which can lead to a situation in which audit quality is too variable. On the other hand, another subgroup questioned the value of the ISA in municipal auditing because municipal auditing has its own special traits accommodated to the municipal audit requirements.

Another subgroup interpreted the situation as being that the good chartered public finance auditing practice recommendation repeats the principles of the ISA, and so there is no need for separate public sector audit guidance. Those who favoured only ISA principles or do not favour the ISA at all do not want to be burdened with very detailed regulations.

Several comments about the oversight function in the Finnish Patent and Registration Office were important. Several respondents wanted controllers to have better competence and knowledge regarding the true content of municipal auditing. Auditors also criticized the documentation requirements as exaggerated and causing unnecessary work. These comments highlight differences in understanding good chartered public finance auditing practice between the auditor oversight function and practising auditors.

We also interviewed a small Finnish audit firm that conducts external municipal auditing. It seems that municipalities have a minimum requirement for recent auditor experience in the last three to five years. If a small audit firm has not won bids in recent years, it cannot tender. This means that the Finnish audit market has been concentrated in a few large audit firms.

At the time of our study, two big audit firms were dominating the municipal audit market. Both audit firms had their own internal quality assurance processes, ethical rules and internal training systems (teaching good chartered public finance auditing practice and the ISA). These two firms wanted to stay in the municipal audit market. They argued that they were able follow the good chartered public finance auditing practice and monitor the quality of their audit engagements. However, three of the Big 5 firms had mainly withdrawn from the Finnish municipal auditing market after being active there for several years. These audit firms emphasized the ISA in all audit engagements, municipal auditing included, and this policy and the low municipal audit prices drew them to the conclusion that Finnish municipal audit market was not an attractive business proposition.

Discussion

Our findings suggest that 70% of Finnish CPFAs often voluntarily adopt the ISA, despite a regulatory environment where this is not strictly required in local government audits. A reason for not adopting ISA is its emphasis on themes which are relevant to private sector companies (for example net sales and inventory).

Our interviews strengthened our understanding of which auditors apply the ISA in Finnish municipal auditing. The big firms have their own internal quality assurance processes, ethical rules and internal training systems, which cover the Finnish municipal auditing standards and the ISA. They did not see meaningful conflicts between the international and Finnish municipal auditing standards. So, they have the knowledge and their own reasons to apply the ISA voluntarily in municipal audits. On the other hand, some big audit firms have mainly withdrawn from the Finnish municipal auditing market. Low audit prices and following ISA standards could be the problem.

All CPFAs who answered to our first question that they use the ISA were asked how they actually use the ISA standards. Our results showed that there was considerable variation in the way municipal auditors use the ISA. The heterogeneous way of applying the ISA is likely to increase the lack of unity in Finnish municipal auditing in this respect. The need for unity can be seen as a reason for further discussion on whether auditors in Finland should adopt the ISA as part of the good chartered public finance auditing practice. One question was related to how clear respondents considered the Finnish good chartered public finance auditing practice. A majority of the respondents, 60%, considered the guidance accurate. However, 40% of respondents answered that there is inaccuracy or vagueness in the way the Finnish good chartered public finance auditing practice has been defined. Some auditors included in this study criticized the Finnish good chartered public finance auditing practice for being too loose, which can lead to a situation in which audit quality is too variable. On the other hand, some auditors questioned the value of the ISA in municipal auditing because municipal auditing has its own special features. Some auditors do not want to be burdened with the very detailed ISA. Thus, we noticed that there are many reasons to question adopting the ISA in municipal audits.

It is necessary to add to this discussion the possibility of fear of the Finnish Audit Oversight Board in the Finnish Patent and Registration Office, which controls the quality of Finnish municipal audits and auditors. In a separate question about the oversight function, several respondents wished the oversight controllers had better competence and knowledge regarding the true content of municipal auditing. Auditors also criticized the documentation requirements, which are exaggerated and cause unnecessary work. These comments and results show that some auditors may perform extra work in order to comply with assumed or unclear requirements from the Finnish Audit Oversight Board and that extra work could include the voluntary adoption of the ISA.

When interpreting our results using institutional theory (DiMaggio & Powell, Citation1983), its seems that the Audit Oversight Board, with its strong emphasis on the ISA as a source of sound and good private sector auditing, diffuses normative pressures to municipal audit practices to increasingly adapt ISA rules. Our findings are in line with existing literature suggesting that institutional factors have a significant impact on ISA adoption (Boolaky & Soobaroyen, Citation2017). Our survey showed that about 70% of CPFAs already more or less followed the ISA. The influence of the Oversight Board is a force belonging to the normative category in institutional theory. It seems that its influence will grow in the future. However, normative isomorphism does not necessarily lead auditors to more efficient and effective auditing. Generic standards, such as the ISA, are incapable of linking their contents with certain specific municipal audit service characteristics. For instance, in the Finnish context, external professional auditing is aimed, among other things, at reducing central government control over the use of state subsidies for local government service production. That is why the auditing of grants-in-aid is one of the obligatory audit tasks stipulated in the Citation2015) for CPFAs. Audit of administration is also a task stipulated in the Citation2015). The ISA does not instruct explicitly on how to audit administration as a specific area of statutory audit. These and some other special characteristics of municipal auditing create a barrier to direct adoption of ISA standards originating from the private sector.

DiMaggio and Powell (Citation1983, p. 155) suggested that uncertainties and ambiguities of the goals of an organization might be one way to explain the behaviour of audit firms. The institutional force of coercive regulatory power did not exist in Finland at the time of our research—it was not mandatory to follow ISA. However, drawing from Deegan (Citation2001, pp. 272–273), coercive isomorphism can be supported by the managerial branch of stakeholder theory as auditors might be satisfying the demands of powerful stakeholders, such as auditor oversight, in terms of voluntarily adopting the ISA. Our survey revealed that learning by imitation has not led audit companies to fully adopt the ISA in municipal sector auditing. The actual impact has, rather, been to hold onto the leeway for professional judgment at the audit firm level. There were no success stories at the audit firm level in fully adopting the ISA (Oulasvirta et al., Citation2021). These results can be compared to the observation that the Finnish public sector accounting tradition has resisted adopting the IPSAS—having deemed them to be an unsatisfactory solution to tax-financed public sector entities (Oulasvirta, Citation2014). Business sector accounting and auditing rules cannot reach full penetrating power in a country with well-developed and established domestic accounting and audit institutions.

Our study confirms that isomorphic mechanisms of institutional theory (DiMaggio & Powell, Citation1983) are evident in framing rules and practices in auditing. Compliance with ISA is actively instructed by the Finnish national audit oversight body for all auditors. On the other hand, isomorphic forces should not be overemphasized (Dacin & Dacin, Citation2008; Adhikari et al., Citation2013). Our results show that changes in established audit practices are not frictionless, and that change efforts should be analysed in the context of strongly varying public sector audit institutions across countries (Brusca et al., Citation2015).

Conclusion

Our results show that there is a clear need to develop municipal auditing, and one solution would be to unravel the problem of how far we should adapt domestic municipal auditing standards to the ISA. This conclusion gains support when we consider the observations of the Finnish Audit Oversight Function in the Finnish Patent and Registration Office identifying problems in municipal auditing. During 2016–2020, more than a quarter of selected audit engagements undertaking quality inspection did not achieve an approved result. Although the Audit Oversight Function undertakes municipal audit quality inspection according to the Finnish good chartered public finance auditing practice criteria, in reality it also uses suitable ISA practices as supporting criteria. This quality inspection result is a remarkable observation that has, on one hand, raised questions among municipal auditors as to whether the quality evaluation criteria of the Oversight Function are reasonable and fair. However, the results emphasize the importance of quality oversight and inspection in developing sound and good audit practice in Finnish municipal auditing.

In addition, our study emphasizes the need to clearly and transparently rule on and advise local government audit practice on the use of private sector focused international audit standards. Local government requires a special audit standardization solution which is not present in the ISA.

Our study has limitations, for example our survey was sent to auditors operating in a single country. The content and regulation of municipal auditing varies across countries and therefore the generalization of the results is limited. To form a deeper understanding of the voluntary adoption of private sector driven audit standards in public sector auditing, additional research based on data from other countries is needed. Future research should explore the voluntary adoption of ISA standards in the public sector with larger multi-year datasets from several countries. We also encourage researchers to further examine this phenomenon at different levels of public administration.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Adhikari, P., Kuruppu, C., & Matilal, S. (2013). Dissemination and institutionalization of public sector accounting reforms in less developed countries: A comparative study of the Nepalese and Sri Lankan central governments. Accounting Forum, 37(3), 213–230.

- Association of Finnish Local and Regional Authorities. (2022). Finnish municipalities and regions. https://www.localfinland.fi/finnish-municipalities-and-regions.

- Bisogno, M., Grossi, G., Manes-Rossi, F., & Santis, S. (2022). Standardizing local governments’ audit reports: For better or for worse? Public Money & Management, DOI: 10.1080/09540962.2022.2064563

- Boolaky, P. K., & Soobaroyen, T. (2017). Adoption of International Standards on Auditing (ISA): Do institutional factors matter? International Journal of Auditing, 21(1), 59–81.

- Broberg, P., Tagesson, T., Argento, D., Gyllengahm, N., & Mårtensson, O. (2017). Explaining the influence of time budget pressure on audit quality in Sweden. Journal of Management & Governance, 21(2), 331–350.

- Brusca, I., Caperchione, E., Cohen, S., & Rossi, F. M. (eds.). (2015). Public sector accounting and auditing in Europe. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Carpenter, V. L., & Feroz, E. H. (2001). Institutional theory and accounting rule choice: An analysis of four U.S. State Governments’ decisions to adopt generally accepted accounting principles. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 26, 565–596.

- Christiaens, J., Vanhee, C., Manes-Rossi, F., Aversano, N., & Van Cauwenberge, P. (2015). The effect of IPSAS on reforming governmental financial reporting: an international comparison. International Review of Administrative Sciences, 81(1), 158–177.

- Collin, S.-O. Y., Tagesson, T., Andersson, A., Cato, J., & Hansson, K. (2009). Explaining the choice of accounting standards in municipal corporations: Positive accounting theory and institutional theory as competitive or concurrent theories. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 20(2), 141–174.

- Coram, P., Ng, J., & Woodliff, D. (2003). A survey of time budget pressure and reduced audit quality among Australian auditors. Australian Accounting Review, 13(29), 38–44.

- Dacin, M. T., & Dacin, P. A. (2008). Traditions as institutionalized practice: Implications for deinstitutionalization. In R. Greenwood, C. Oliver, R. Suddaby, & K. Sahlin (Eds.), The Sage handbook of organizational institutionalism. Sage.

- DeAngelo, L. E. (1981). Auditor size and audit quality. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 3(3), 183–199.

- Deegan, C. M. (2001). Financial accounting theory. McGraw-Hill.

- Degeling, P., Anderson, J., & Guthrie, J. (1996). Accounting for public accounts committees. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal, 9(2), 30–49.

- DiMaggio, P. J., & Powell, W. W. (1983). The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. American Sociological Review, 48(2), 147–60.

- Dimaggio, P. J., & Powell, W. W.. (1991). Introduction. In W. W. Powell & P. J. DiMaggio (Eds.), The new institutionalism in organizational analysis. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Francis, J. R. (2004). What do we know about audit quality? The British Accounting Review, 36(4), 345–368.

- Halim, A., Sutrisno, T., Rosidi, & Achsin, M. (2014). Effect of competence and auditor independence on audit quality with audit time budget and professional commitment as a moderation variable. International Journal of Business and Management Invention, 3(6), s. 64–74.

- Hay, D., & Cordery, C. (2018). The value of public sector audit: Literature and history. Journal of Accounting Literature, 40, 1–15.

- International Auditing and Assurance Standards Board (IAASB). (2022). A new standard for audits of less complex entities. https://www.iaasb.org/focus-areas/new-standard-less-complex-entities.

- Johnsen, Å, Meklin, P., Oulasvirta, L., & Vakkuri, L. (2004). Governance structures and contracting out municipal auditing in Finland and Norway. Financial Accountability & Management, 20(4), 445–477.

- Julkishallinnon ja -talouden tilintarkastajat ry. (2012). Kuntien mukautetut tilintarkastuskertomukset (Modified audit reports in municipalities).

- Knechel, W. R., Krishnan, G. V., Pevzner, M., Shefchik, L. B., & Velury, U. K. (2013). Audit quality: Insights from the academic literature. Auditing: A Journal of Practice, 32(Supplement 1), 385–421.

- Lapsley, I., & Miller, P. (2019). Transforming the public sector: 1998–2018. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal, 32(8), 2211–2252.

- Local Government Act. (365/1995). (Kuntalaki 365/1995).

- Local Government Act. (410/2015). (Kuntalaki 410/2015).

- Manes Rossi, F., Cohen, S., Caperchione, E., & Brusca, I. (2016). Harmonizing public sector accounting in Europe: Thinking out of the box. Public Money & Management, 36(3), 189–196.

- Manes Rossi, F., Brusca, I., & Condor, V. (2021). In the pursuit of harmonization: Comparing the audit systems of European local governments. Public Money & Management, 41(8), 604–614.

- Mattei, G., Grossi, G., & Guthrie, J. (2021). Exploring past, present and future trends in public sector auditing research: A literature review. Meditari Accountancy Research, 29(7), 94–134.

- Mitchell, R. K., Agle, B. R., & Wood, D. J. (1997). Toward a theory of stakeholder identification and salience: Defining the principle of who and what really counts. Academy of Management Review, 22(4), 853–886.

- Oulasvirta, L. (2014). The reluctance of a developed country to choose International Public Sector Accounting Standards of the IFAC. A critical case study. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 25, 272–285.

- Oulasvirta, L., Uoti, A., Ojala, H., Saastamoinen, J., Pesu, J., Kettunen, J., Paananen, M., Anttila, V., & Lindgren, H. (2021). Kuntien tilintarkastuksen laatu ja toimivuus: Nykytila ja kehittämistarpeet. Valtioneuvoston selvitys- ja tutkimustoiminnan julkaisusarja, 2021, 11.

- Stewart, J. (2006). Auditing as a public good and the regulation of auditing. Journal of Corporate Law Studies, 6(2), 329–360.

- Suomen tilintarkastajat ry. (2020). Julkishallinnon hyvä tilintarkastustapa (Good chartered public finance auditing practice). https://tilintarkastajat.fi/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/julkishallinnon-hyva-tilintarkastustapa-final-01062020-2.pdf.

- Tagesson, T., Glinatsi, N., & Prahl, M. (2015). Procurement of audit services in the municipal sector: The impact of competition. Public Money & Management, 35(4), 273–280.

- Tepalagul, N., & Lin, L. (2015). Auditor independence and audit quality: A literature review. Journal of Accounting, Auditing & Finance, 30(1), 101–121.

- Vaasa Court of Appeals. (2019). Judgment 31.1.2019, Number 19/104154.

- Vakkuri, J., Meklin, P., & Oulasvirta, L. (2006). Emergence of markets—instututional change of municipal auditing in Finland. Nordiske Organisasjonsstudier, 1- 2006, Fagbokforlaget, 31–55.