?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.IMPACT

Discretion in the financial reporting process can help reveal private information to external parties; it can also be used to avoid disclosing information that makes agents vulnerable to criticism—especially under strong political incentives to avoid transparency. This must be taken into account by higher levels of governments when designing and implementing balanced-budget requirements tied to financial reporting figures produced on an accrual basis, as well as by other stakeholders using accrual-based information for monitoring purposes.

ABSTRACT

In 2013, an accounting reform permitted Swedish municipalities to voluntarily adopt a system with accrual reserves that was designed to increase flexibility in meeting budget requirements and decrease regulatory incentives to engage in earnings management. However, since a system with accrual reserves imposes potentially undesirable transparency from the perspective of politicians, it is unclear whether the (regulatory) benefits of adopting accrual reserves are perceived to exceed the (political) costs. The authors found that municipalities with higher levels of earnings management were less likely to adopt a system of accrual reserves, and they attribute this to political incentives to avoid transparency.

Introduction

A recent literature review indicates that earnings management in subnational governments (mostly municipalities), and in entities operating within subnational or national governments (mostly healthcare trusts), is receiving increasing scholarly attention (Bisogno & Donatella, Citation2022). Thus far, most of this literature relies on theories from the rational decision-maker paradigm, such as agency theory (Greenwood & Zhan, Citation2019; Pina et al., Citation2012) and public choice theory (Cohen & Malkogianni, Citation2021; Ferreira et al., Citation2013), which build on the assumption that all individuals involved in the financial reporting process are calculative utility maximizers who weigh the perceived benefits of a specific decision against potential costs. Therefore, the literature has mainly focused on how agents respond to different types of incentives (Anagnostopoulou & Stavropoulou, Citation2021; Beck, Citation2018; Cohen et al., Citation2019; Greenwood et al., Citation2017; Pilcher & Van der Zhan, Citation2010) or to combinations of incentives and monitoring arrangements, where the latter is expected to offset the former (Donatella et al., Citation2019; Greenwood & Zhan, Citation2019).

However, a close reading of the above-mentioned literature reveals notable differences in the types of incentives that have been empirically tested. There are two main reasons for this. First, research dealing with entities operating within subnational or national governments tends to relate earnings management incentives to the managers running these organizations, whereas research on subnational governments relates these incentives to the politicians in office. Second, managers and politicians differ regarding the regulatory and political pressures they are exposed to. In entities where managers typically operate under a very strict regulatory regime within subnational or national governments, incentives for earnings management are mainly attributed to the predefined financial performance targets managers are required to meet (Ballantine et al., Citation2007; Greenwood et al., Citation2017; Ibrahim et al., Citation2019; Pina et al., Citation2012). In contrast, in a subnational government setting, incentives for earnings management are usually attributed to the accountability pressure stemming from both higher levels of government and voters (Arcas & Martí, Citation2016; Pilcher & Van der Zhan, Citation2010; Stalebrink, Citation2007). More specifically, a common assumption underlying empirical research is that politicians engage in earnings management because it allows them to avoid political costs presumably arising from the disclosure (to voters) of a negative or large positive net income (i.e. political incentives), or from a failure to meet predefined financial performance targets set by higher levels of government (i.e. regulatory incentives). These assumptions are consistent with empirical findings in subnational governments, suggesting that earnings management exists to aid the reporting of a positive net income close to zero (for example Arcas & Martí, Citation2016; Cohen & Malkogianni, Citation2021), and that earnings management tends to increase under certain conditions, including in proximity to elections (Cohen et al., Citation2019; Kido et al., Citation2012) and in competitive political environments (Donatella, Citation2020; Ferreira et al., Citation2013, Citation2020).

The aim of this article is to offer further insight into how regulatory and political incentives shape the reporting behaviour of subnational governments. We exploit data from a balanced-budget requirement reform in Swedish municipalities in 2013, which allowed municipalities to voluntarily adopt a system with accrual reserves. The system was designed to offer municipalities relief regarding how budget resources are allowed to be allocated across years and was thus intended to decrease regulatory incentives to engage in earnings management. At the same time, the nature of this system forces potentially undesirable transparency, from the perspective of politicians. Municipalities must risk reporting a large positive net income to be able to reserve accruals, and a negative net income to be able to use previously reserved accruals. Given that reporting either a large positive net income or a negative income may be politically challenging, the cost of adopting accrual reserves may exceed the intended benefits.

The reform offers an opportunity to investigate municipalities’ regulatory and political incentives. Using a municipality’s level of earnings management prior to the reform as a proxy for political and regulatory incentives to meet budget balance requirements, we tested the probability of adopting accrual reserves and found that higher levels of earnings management were associated with lower rates of adoption. This suggests that political incentives outweigh regulatory incentives in the studied setting.

Reporting incentives under regulatory and political pressures

Theoretical background

In the context of municipalities, several scholars use the agency framework when predicting and explaining earnings management behaviour (for example Arcas & Martí, Citation2016; Donatella, Citation2020; Ferreira et al., Citation2020). The basic assumptions of agency theory, as described in the seminal paper by Jensen and Meckling (Citation1976) in the context of the firm, also apply when the theory is used in a municipal context. Essentially, these assumptions are that all parties are calculative utility maximizers; information asymmetry arises when decision authority over resources is delegated from one party (the principal) to another (the agent); and monitoring costs are non-zero (Baber, Citation1983; Ingram & DeJong, Citation1987; Zimmerman, Citation1977). However, the political market has certain peculiarities that must be considered when discussing earnings management incentives and predicting accrual reserves adoption.

The literature that uses agency theory in a municipal context typically emphasizes the existence of multiple layers of agency relationships, such as between politicians, managers, voters, higher levels of governments, and other resource providers (Ingram & DeJong, Citation1987; Zimmerman, Citation1977). Rather than covering all potential agency relationships, we focus on those most relevant to earnings management—namely, the agency relationships between ruling politicians in a municipality on the one hand and the national government and voters on the other.

National governments act as principals in that they delegate tasks to subnational governments while retaining legislative power and partial control over municipal revenues through the distribution of municipal grants. The agency relationship between voters and ruling politicians stems from the fact that most voters are both service recipients and resource providers. The high level of decentralization in the provision of public services in Sweden means that municipalities provide many of the services that voters are affected by and use in their daily lives. Given that voters’ wealth is closely tied to the policies implemented by municipalities, voters incur agency costs to the extent that their interests are misaligned with those of the politicians in office.

Below, we discuss incentives for earnings management stemming from regulatory pressure from national governments and political pressure from the general public through voting rights. Whether a system of accrual reserves can reduce earnings management practices (and thus function as intended) depends on the relative prevalence and strength of the regulatory and political incentives.

Managing or reserving accruals: Incentives under regulatory and political pressures

With respect to regulatory pressure in Swedish municipalities, earnings management incentives arise from the benefits associated with balanced-budget compliance, such as securing grants from the national government and avoiding stricter regulations that reduce municipalities’ autonomy. Incentives are especially strong when the risk of detection is low. However, with the adoption of accrual reserves, the relative benefits of earnings management decrease. A system of accrual reserves that allows Swedish municipalities to cover all or part of a deficit that would normally have to be restored by equivalent surpluses within three years offers municipalities flexibility without the need to resort to earnings management.

With respect to political pressure, ruling politicians have incentives to report a financial performance that benefits them politically and increases their chances of re-election. Typically, politicians are expected to prefer reporting a positive net income close to zero, as a negative or large positive net income on the face of the statement of financial performance increases politicians’ vulnerability to criticism. When the main source of revenue is taxes and/or grants, reporting a large positive net income may be seen as indicating excessive taxation or showing that more resources could have been allocated to improve the quality of services provided (Pilcher & Van der Zhan, Citation2010; Stalebrink, Citation2007). Conversely, reporting a negative net income risks signaling irresponsible policies in the past (Arcas & Martí, Citation2016; Ferreira et al., Citation2013) and suggests that unpopular policies may be necessary to support a balanced budget in the future—such as an increase in the tax burden or a decrease in the quality of services (Pilcher & Van der Zhan, Citation2010).

As with regulatory pressure, incentives to manage earnings are especially strong when the risk of detection is low. As explained by Zimmerman (Citation1977), since there are factors that diminish the potential benefits associated with becoming informed on a political market, voters are unlikely to be willing to incur any substantial monitoring costs. The factors referred to are ownership concentration and capitalization. Each individual voter has a limited claim on the public service potential, and under public property rights, there are restrictions on sales of claims; moreover, with no market for capitalizing present values, a failure to monitor current political actions is less costly. Furthermore, assuming a voter is prepared to incur the necessary costs of becoming informed, a single vote is unlikely to affect the outcome of an election. Mass media and special interest groups are therefore considered to be important intermediaries (Baber, Citation1983), as they enjoy potential economies of scale when monitoring governments. However, both Zimmerman (Citation1977) and Watts and Zimmerman (Citation1986) predict that the costs of becoming informed on a political market are, on average, too high to be justified, even for these groups. This is an important assumption because, if neither voters nor intermediates are willing to incur the cost of unraveling earnings management, then the risk ruling politicians carry when taking advantage of accounting measurement discretion to avoid disclosing financial information that may hurt their political ambitions (for example re-election, career advancement, or the chance of implementing a specific policy) will depend on monitoring from other parties, such as auditors and oversight bodies.

Sweden has weak national government monitoring of financial performance and reporting of individual municipalities, as well as a weak municipal audit function. Although this means that the risk associated with engaging in a questionable accounting practice is low, it is not zero. If irregularities are publicly exposed, they are likely to impose political costs on ruling parties. Therefore, the adoption of accrual reserves may offer relief regarding the allocation of budget resources over time, without the need to carry the risk associated with earnings management.

Prior research and our research question

Following the implementation of accrual-based reporting in the public sector, there has been a growing literature on earnings management in municipalities, especially in Europe (for example Arcas & Martí, Citation2016; Cohen et al., Citation2019; Cohen & Malkogianni, Citation2021; Donatella, Citation2020; Ferreira et al., Citation2013), but also elsewhere, such as in Australia (Pilcher & Van der Zhan, Citation2010) and the USA (Beck, Citation2018). However, to the best of our knowledge, no studies have empirically investigated the link between predefined financial performance targets and earnings management behaviour at the municipal level. Nevertheless, in the existing empirical literature on municipalities, it is a common assumption that earnings management is triggered by political and regulatory pressures (Arcas & Martí, Citation2016; Pilcher & Van der Zhan, Citation2010; Stalebrink, Citation2007).

In the related literature on earnings management in entities operating within subnational or national governments, several studies in the context of the English National Health Service have been designed to empirically test how regulatory pressure impacts earnings management. More specifically, Ballantine et al. (Citation2007) used data from a period when there was a financial breakeven target in force and found a spike in the distribution of reported net income just above zero. Greenwood et al. (Citation2017) made use of data from a period when a more divergent set of financial performance metrics was used alongside a borrowing limit and found that trusts tend to have positive discretionary accruals when their pre-managed performance is below thresholds that trigger government interventions, whereas trusts with a pre-managed performance above these thresholds tend to have negative discretionary accruals. Anagnostopoulou and Stavropoulou’s (Citation2021) study covers the periods before and after some English hospitals applied for and were granted foundation trust status, allowing them to operate more autonomously. Interestingly, observations of positive discretionary accruals in the pre-period suggest that hospitals tended to manage financial performance upwards before applying for foundation trust status and that the reported financial performance declined in the post-period, which is partly attributable to the fact that previous positive discretionary accruals were reversed. Taken together, the studies by Ballantine et al. (Citation2007), Greenwood et al. (Citation2017), and Anagnostopoulou and Stavropoulou (Citation2021) show results consistent with the idea that managers in healthcare trusts exercise discretion over accruals in order to meet predefined financial performance targets. However, those studies investigate earnings management in the context of the implementation of tighter, not looser, financial performance targets, in contrast to the case of the system of accrual reserves adopted in Swedish municipalities.

Consistent with prior empirical literature, and in line with agency theory, in the absence of a system of accrual reserves, we expected that the presence of regulatory and political pressure would increase the likelihood of earnings management in Swedish municipalities. It remains an empirical question whether incentives to manage earnings are offset by a system of accrual reserves that caters to regulatory incentives to meet budget requirements but simultaneously introduces (politically risky) transparency. As noted by Chan (Citation2003, p. 13), because giving out information means ceding authority, ‘government officials rationally do not volunteer more information than is required or in their interest … it is therefore not surprising that, while some accounting is done on a voluntary basis, financial disclosure is often made only in response to demand’. Extending this reasoning to the voluntary adoption of accrual reserves, it is not clear a priori whether the benefits associated with increased flexibility in the permitted use of budget resources exceed the costs associated with the inevitable disclosure of politically challenging bottom-line figures that such adoption would bring.

Using a municipality’s level of earnings management in the pre-adoption period as a proxy for regulatory and political pressures to meet budget balance requirements, we examined the following research question:

Are municipalities with higher levels of earnings management in the pre-adoption period more or less likely to adopt accrual reserves?

Institutional background and reforms

Implementation of a balanced-budget requirement

When Sweden was hit by a financial crisis in the early 1990s, which resulted in austerity measures at all levels of governments, the national government imposed a balanced-budget requirement on municipalities, in order to establish a minimum financial performance threshold. As was made clear in the bill preparing the amendment of the Municipal Act (government bill No. 1996/97:52), requiring year-end budgets to be balanced would not be effective if the financial reporting in the municipal sector suffered from major comparability and reliability issues. Hence, the Municipal Accounting Act (No. 1997:614) was adopted in 1998 to harmonize financial reporting and, two years later, the balanced-budget requirement took effect. The Municipal Accounting Act refers to generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP), which are the standards and statements issued by the Swedish Council for Municipal Accounting (SCMA). As both the Act and the SCMA standards are accrual- and principles-based, they introduce substantial discretion in financial reporting and thereby create room for earnings management behaviour.

Considering that the financial reporting framework relies on what Oulasvirta (Citation2021, p. 443) refers to as ‘the transaction-based, historical costs and income-statement-first approach’, the logical solution pursued by the national government was to tie the balanced-budget requirement to the statement of financial performance (Brorström, Citation1997). The language used in the Municipal Act was that ‘revenues should cover expenses’ every year. In the government bill (No. 1996/97:52), it was specified that net income must be positive after adjusting for capital gains and losses and unrealized losses on securities and reversals from such unrealized losses (henceforth, adjusted net income). Unless a negative adjusted net income is due to an exceptional situation, it must be restored by an equivalent positive adjusted net income within the next two years (applied in the 2000–2004 period) or three years (applied from 2005 and onwards).

An important contextual feature is that neither the adoption of the Municipal Accounting Act, nor the balanced-budget requirement, were supported with strong enforcement mechanisms. The national government has no formal system for monitoring the balanced-budget compliance of individual municipalities. Instead, as depicted in a recent government inquiry (No. 2021:75), the emphasis from the national governments’ side is on monitoring the aggregated financial performance of the municipal sector. Moreover, the Swedish National Audit Office is not involved in the auditing of financial reporting. Instead, it is the municipal council that approves the audit budget and appoints a committee with political auditors, which are in turn required to appoint professional auditors to assist them in their work. It is also noteworthy that there are no legal sanctions for non-compliance with the Municipal Accounting Act and related GAAP.

Amending the balanced-budget requirement: Adoption of accrual reserves

In the late 2000s, when the global financial crisis started and forecasts of reduced tax revenues were released, austerity measures were once again anticipated to hit Swedish municipalities. One of the issues raised by representatives of the municipal sector was that an amended balanced-budget requirement would improve the sector’s ability to adapt to anticipated changes in economic conditions by allowing more flexibility in the calculation of adjusted negative net income. Following these discussions, the national government established an inquiry in 2010, which resulted in the proposal of a system based on accrual reserves to smooth the budget resources (government inquiry No. 2011:59). The bill was passed in autumn 2012, and the system took effect in 2013. In the bill preparing the amendment, it was also explicitly stated that this system aimed to decrease incentives for municipalities to engage in earnings management (government bill No. 2011/2012:172, p. 23).

The adoption of accrual reserves is voluntary. However, for municipalities that decide to use such reserves, a threshold for when resources are allowed to be reserved is specified in the Municipal Act. This should be based on the lowest of net income (as reported on the bottom line of the statement of financial performance) and the adjusted net income. As part of the amended Municipal Accounting Act, since 2013, municipalities are required to disclose these adjustments in a separate financial statement in the annual report: the ‘year-end balanced-budget statement’. Municipalities with a positive (negative) equity ratio are allowed to reserve the part of net income or adjusted net income that exceeds 1% (2%) of their tax revenues and government grants.

If the adjusted net income is negative, and the threshold for a year-end balanced budget is not met, the accrual reserves can be used to cover all or a part of the deficit, which would otherwise have had to be restored by an equivalent positive adjusted net income within the next three-year period. According to the government bill (No. 2011/2012:172, p. 30), this opportunity should be used when tax revenues grow at a decreasing rate; the suggested threshold is when forecasts of tax revenues are below the 10-year average. However, this is not a requirement included in the Municipal Act, which allows municipal councils to make this decision at their own discretion, increasing the flexibility of the system.

To be compliant with the Municipal Accounting Act, the total amount of accrual reserves should be disclosed in the statement of financial position as a sub-item of equity, and the annual accruals reserved or used should be disclosed in the year-end balanced-budget statement. More specifically, the bottom line of the year-end balanced-budget statement should reflect the adjusted net income after accruals are reserved or used. In contrast, accrual reserves are not accounted for in the statement of financial performance and will thus have no direct effect on the reported net income. Therefore, when accruals are reserved, a large positive net income is likely to be reported on the bottom line of the statement of financial performance and, when resources are used from accrual reserves, the bottom-line figure of the statement of financial performance is likely to be negative.

Research design

Methodology for data collection

Our empirical analysis consisted of two consecutive steps. First, we estimated the level of earnings management in municipalities based on their abnormal accruals. For this step, we used panel data for all of Sweden’s 289 municipalities (Gotland was excluded due to its hybrid status as a municipality/region). Second, we constructed regression models to answer our research question by focusing on the cross-section of municipalities in 2013—the year in which the system of accrual reserves was introduced.

For the estimation of abnormal accruals (step 1), we obtained historical accounting data from Statistics Sweden for 2000–2018. We restricted the sample to this period, because the Municipal Bookkeeping and Accounting Act (No. 2018:597) replaced the Municipal Accounting Act (No. 1997:614) in 2019, and this shift implied several major changes to the financial reporting framework that would affect the estimation of discretionary accruals. We excluded outliers defined as the top centile of municipality-year observations based on the absolute percentage change in total assets (as extreme growth may lead to errors in the abnormal accruals estimation).

To identify accrual-reserve adopters (step 2), we collected the annual reports for the year 2013. For non-adopters, we collected further annual reports up to 2018 to determine potential late adoption (30 municipalities). The rationale for excluding late adopters from the main analysis was that late adopters potentially differ from early adopters with respect to their incentive structures—making it conceptually desirable to avoid mixing early and late adopters and to keep the sample as homogeneous as possible. After dropping an additional six municipalities with outlier observations in 2013, the final sample for the cross-sectional tests comprised 253 municipalities.

Estimating earnings management

There is currently no standard approach for estimating earnings management in the public sector context. As illustrated in a literature review by Bisogno and Donatella (Citation2022), some scholars develop their own models or approaches, whereas others rely on well-known models developed in the private sector context, like the Jones (Citation1991) model. We used the Jones model as a point of departure to estimate earnings management. This model assumes that abnormal accruals can be represented by residuals in the regression of total accruals on an estimate of non-discretionary accruals. The variation in total accruals that remains unexplained by the non-discretionary component must be discretionary (and is captured by the residuals or error terms).

Total accruals (TA) comprise a non-discretionary (NDA) and discretionary (DA) component:

Empirically, we first calculated TA and NDA for each municipality i in year t:

where:

= Year-on-year changes in revenues,

= Total property, plant, and equipment,

= Year-on-year changes in current assets,

= Year-on-year changes in current liabilities,

= Year-on-year changes in cash, and

= Total depreciation in property, plant, and equipment.

We then estimated DA as the absolute value of the residual () from a time-series regression of the TA on the non-discretionary component, by municipality:

(1)

(1) All variables (and the intercept) were scaled by beginning-of-year total assets (

). In total, we ran 289 regressions with 19 observations in each.

The private sector accounting literature contains a number of methodological discussions concerning the most appropriate estimation technique. Several of the suggested amendments are applicable only to firms (not municipalities), such as the inclusion of a variable measuring changes in receivables to account for revenues from credit sales (Dechow et al., Citation1995). However, many discussions focus on how the data should be grouped (for example Kothari et al., Citation2005; Collins et al., Citation2017), assuming that a shortage of data on any individual firm requires firms to be pooled based on size, mean performance, industry, or some other factor believed to capture accruals formation. We therefore re-estimated Equationequation 1(1)

(1) with the following two variations: (1) The data was pooled over time instead of over municipality—that is, we estimated DA per year on the cross-section (N = 289 per regression); and (2) the data was divided into deciles based on performance (net income scaled by revenues) and, as before, pooled over time (N ≈ 29 [= 289/10]) per regression. We called the main and two complementary measures DA1, DA2, and DA3, respectively.

For each DA measure, we calculated the mean value of abnormal accruals over a 10- and five-year period leading up to 2013—the first year permitting the adoption of accrual reserves. We thus obtained the average level of earnings management per municipality, which constitutes the input variable for the cross-sectional tests in subsequent analyses.

Regression model to explain accrual reserves adoption

To test whether adopters of accruals reserves differ from non-adopters in their average level of earnings management, we estimated the following logistic regression model:

(2)

(2) where ARA is an indicator variable coded as ‘1’ for accrual reserves adopters and ‘0’ for non-adopters; DA represents mean discretionary accruals (DA1, DA2, or DA3), a measure of earnings management; subscript i refers to municipality I;

denotes the logit function; and ei refers to the entity-specific regression residual. To address potential correlation among residuals within a region, we clustered standard errors by region. Note that the alternative use of heteroscedasticity-robust standard errors does not alter inferences (untabulated robustness tests). All control variables and their predicted associations with the depenedent variables are described in , while summary statistics of the data are presented in .

Table 1. Variable descriptions.

Table 2. Sample selection and summary statistics of the variables.

Empirical analysis

Descriptive statistics

To investigate the potential association between earnings management and the probability of accrual reserves adoption, we compared the pre-2013 mean absolute discretionary accruals between adopters and non-adopters. As shown in , adopters had significantly lower discretionary accruals, and these results were robust across all accrual estimations (DA1, DA2, and DA3) and to mean calculations using either a 10- or five-year window (the exception was meanDA15). However, t-tests consistently produced lower statistical significance for the five-year specification.

Table 3. The t-tests performed.

To ensure that these findings were not produced by confounding effects unrelated to the actual adoption of accrual reserves, we performed a number of regression analyses, as described in Equationequation 2(2)

(2) .

Regression analysis and results

presents the results from a logistic regression model that relates the probability of adopting accrual reserves to mean discretionary accruals, while controlling for measures such as municipality mean performance, size, voter participation, grant dependence, and political competition. We found that the model as a whole has non-negligible explanatory power, and that the earlier findings based on t-tests were confirmed in a multivariate setting. More specifically, as absolute discretionary accruals increased, the probability of adopting ARA significantly decreased. This held across all specifications of DA (i.e. DA1, DA2, and DA3; see Models 1, 2, and 3, respectively) and for mean calculations using 10- and five-year windows (the exception was meanDA15; see Panels A and B in , respectively).

Table 4. Logistic regression.

The coefficients on the control variables had the expected signs (for an explanation of the predicted associations see ). We found that having a negative equity ratio (negEQ) decreased the probability of adopting accrual reserves, while the relative amount of national government grants received (Grants) increased this probability. Furthermore, we found a positive coefficient on the variables MinGov and GovChange (dummies representing minority government and government change), which we interpreted as the probability of adopting accrual reserves increasing with a more politically competitive environment. When monitoring from the opposition increases, the benefits of more flexibility in the permitted use of budget resources exceed the costs of increased transparency associated with the disclosure of politically challenging bottom-line figures.

Finally, untabulated correlation matrices revealed significant associations between some of the control variables. To ensure that our results were not affected by multicollinearity among the regressors, we repeated all the tests after dropping combinations of the most highly correlated variables and concluded that results are unaltered. For all models, the variance inflation factor (VIF) never exceeded 3.0.

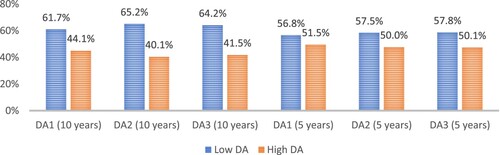

Since coefficients estimated in a logistic regression are not meaningfully interpreted, we calculated the difference in the probabilities of adopting accrual reserves (i.e. the probability that ARA = 1) for two hypothetical values of mean discretionary accruals (): at one standard deviation below the mean (‘low DA’) and at one standard deviation above the mean (‘high DA’).

For mean absolute discretionary accruals one standard deviation below the sample average, the probability of adopting accruals reserves was 60%–65% when the mean was estimated over 10 years and 55%–60% when the mean was estimated over five years. In contrast, for mean absolute discretionary accruals one standard deviation above the sample average, the probability of adoption was 40%–45% for the 10-year estimation window and around 50% for the five-year estimation window.

Taken together, we conclude that municipalities with a higher level of earnings management in the pre-adoption period are—counter to the intention of the regulators—less likely to adopt accrual reserves. This finding suggests that incentives to manage earnings are not adequately addressed by the reform and cannot be supplanted by a system of accrual reserves.

Additional analysis

To provide further assurance that adoption choice is driven by earnings management and not by other unobserved differences between the adoption and non-adoption samples, we repeated all tests after restricting observations in the adoption group to those that could be reasonably matched to observations in the non-adoption group. For each observation in our sample, we calculated a propensity score that captured the probability of a municipality adopting accrual reserves based on the 10-year/five-year mean value of each of the control variables. For each adopter, a non-adopter was found with a similar propensity score; these matched pairs were retained in the sample, while unmatched observations were dropped. More specifically, we applied nearest-neighbour matching without replacement (the same observations in the control group cannot be used as a match multiple times) and with and without caliper restrictions (where a caliper restriction dictates the maximum allowed distance in propensity scores between matched observations). A caliper restriction set at 0.1 is considered a reasonable trade-off between the risks of obtaining matches that are too dissimilar (due to a too-broad caliper) and finding too few matches (due to a too-narrow caliper). It is also, incidentally, the approximate value when calculating the optimal caliper width, as shown through simulations by Austin (Citation2011): 0.2 × .

We also considered late adopters, requiring us to calculate propensity scores for the period 2014–2018. For each late adopter, we found an appropriate match among never-adopters in the same year. summarizes the new samples with and without caliper restrictions.

Table 5. Sample composition after applying matching criteria.

Panels A and B of replicate the results in , but with matching restrictions (controls omitted for the sake of brevity). The significant negative coefficient on mean discretionary accruals in all models point to a robust association between earnings management and the choice to adopt accrual reserves. Panels C and D of show findings for an extended matched sample including late adopters. Again, with the exception of meanDA15, the results remained robust.

Table 6. Logistic regression with matched samples.

Conclusions

The previous literature relates earnings management in subnational governments and entities operating within subnational governments or the national government to regulatory and political incentives. We contribute to this literature by providing an analysis of the relationship between these incentives and earnings management behaviour. Using a municipality’s level of earnings management prior to the reform as a proxy for political and regulatory incentives, we tested the probability of adopting accrual reserves. We found evidence that, compared with non-adopters, the adopters of accrual reserves have lower levels of earnings management in the pre-adoption period. This suggests that the benefits of adoption do not outweigh the cost of increased transparency; we attribute this to the relative strength of political incentives compared with regulatory incentives. In other words, earnings management is the preferred mechanism by which politicians achieve their political and economic goals.

The results from our study, which illustrate that accrual reserves are favoured by municipalities that already have relatively high-quality accruals, can be seen as an indication that the Swedish national government overestimated the regulatory incentives and underestimated the political incentives in play. Whether the balance between regulatory and political incentives is specific to countries that rely on a budget and reporting framework such as the one applied in Swedish municipalities, or whether the same pattern repeats under stricter regulatory regimes, is an avenue for exploration in future earnings management research. Such research may have policy implications concerning the design and implementation of predefined financial performance targets.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Anagnostopoulou, S. C., & Stavropoulou, C. (2021). Earnings management in public healthcare organizations: The case of the English NHS hospitals. Public Money & Management, https://doi.org/10.1080/09540962.2020.1866854

- Arcas, M. J., & Martí, C. (2016). Financial performance adjustment in English local governments. Australian Accounting Review, 26(2), 141–152. https://doi.org/10.1111/auar.12094

- Austin, P. C. (2011). Optimal caliper widths for propensity-score matching when estimating differences in means and differences in proportions in observational studies. Pharmaceutical Statistics, 10(2), 150–161. https://doi.org/10.1002/pst.433

- Baber, W. R. (1983). Toward understanding the role of auditing in the public sector. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 5, 213–227. https://doi.org/10.1016/0165-4101(83)90013-7

- Ballantine, J., Forker, J., & Greenwood, M. (2007). Earnings management in English NHS hospital trusts. Financial Accountability & Management, 23(4), 421–440. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0408.2007.00436.x

- Beck, A. W. (2018). Opportunistic financial reporting around municipal bond issues. Review of Accounting Studies, 23(3), 785–826. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11142-018-9454-2

- Bisogno, M., & Donatella, P. (2022). Earnings management in public sector organizations: A structured literature review. Journal of Public Budgeting, Accounting & Financial Management, 34(6), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPBAFM-03-2021-0035

- Brorström, B. (1997). För den goda redovisningsseden. Studentlitteratur.

- Chan, J. (2003). Government accounting: An assessment of theory, purposes and standards. Public Money & Management, 23(1), 13–20.

- Cohen, S., Bisogno, M., & Malkogianni, I. (2019). Earnings management in local governments: The role of political factors. Journal of Applied Accounting Research, 20(3), 331–348. https://doi.org/10.1108/JAAR-10-2018-0162

- Cohen, S., & Malkogianni, I. (2021). Sustainability measures and earnings management: Evidence from Greek municipalities. Journal of Public Budgeting, Accounting & Financial Management, 33(4), 365–386. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPBAFM-10-2020-0171

- Collins, D. W., Pungaliya, R. S., & Vijh, A. M. (2017). The effects of firm growth and model specification choices on tests of earnings management in quarterly settings. The Accounting Review, 92(2), 69–100. https://doi.org/10.2308/accr-51551

- Dechow, P. M., Sloan, R. G., & Sweeney, A. P. (1995). Detecting earnings management. The Accounting Review, 70(2), 193–225.

- Donatella, P. (2020). Is political competition a driver of financial performance adjustments? An examination of Swedish municipalities. Public Money & Management, 40(2), 122–130. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540962.2019.1667684

- Donatella, P., Haraldsson, M., & Tagesson, T. (2019). Do audit firm and audit costs/fees influence earnings management in Swedish municipalities? International Review of Administrative Sciences, 85(4), 673–691. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020852317748730

- Donatella, P., & Tagesson, T. (2021). CFO characteristics and opportunistic accounting choice in public sector organizations. Journal of Management and Governance, 25(2), 509–534. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10997-020-09521-1

- Ferreira, A., Carvalho, J., & Pinho, F. (2013). Earnings management around zero: A motivation to local politician signalling competence. Public Management Review, 15(5), 657–686. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2012.707679

- Ferreira, A., Carvalho, J., & Pinho, F. (2020). Political competition as a motivation for earnings management close to zero: The case of Portuguese municipalities. Journal of Public Budgeting, Accounting & Financial Management, 32(3), 461–485. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPBAFM-10-2018-0109

- Greenwood, M. J., Baylis, R. M., & Tao, L. (2017). Regulatory incentives and financial reporting quality in public healthcare organisations. Accounting and Business Research, 47(7), 831–855. https://doi.org/10.1080/00014788.2017.1343116

- Greenwood, M. J., & Tao, L. (2021). Regulatory monitoring and university financial reporting quality: Agency and resource dependency perspectives. Financial Accountability & Management, 37(2), 163–183. https://doi.org/10.1111/faam.12244

- Greenwood, M., & Zhan, R. (2019). Audit adjustments and public sector audit quality. Abacus, 55(3), 511–534. https://doi.org/10.1111/abac.12165

- Ibrahim, S., Noikokyris, E., Fabiano, G., & Favato, G. (2019). Manipulation of profits in Italian publicly-funded healthcare trusts. Public Money & Management, 39(6), 428–435. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540962.2019.1578539

- Ingram, R. W., & DeJong, D. V. (1987). The effect of regulation on local government disclosure practices. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 6(4), 245–270. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0278-4254(87)80002-9

- Jensen, M. C., & Meckling, W. H. (1976). Theory of the firm: Managerial behaviour, agency costs and ownership structure. Journal of Financial Economics, 3(4), 305–360. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-405X(76)90026-X

- Jones, J. J. (1991). Earnings management during import relief investigations. Journal of accounting research, 29(2), 193–228. https://doi.org/10.2307/2491047

- Kido, N., Petacchi, R., & Weber, J. (2012). The influence of elections on the accounting choices of governmental entities. Journal of Accounting Research, 50(2), 443–476. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-679X.2012.00447.x

- Kothari, S. P., Leone, A. J., & Wasley, C. E. (2005). Performance-matched discretionary accrual measures. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 39(1), 163–197.

- Oulasvirta, L. (2021). A consistent bottom-up approach for deriving a conceptual framework for public sector financial accounting. Public Money & Management, 41(6), 436–446. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540962.2021.1881235

- Pilcher, R., & Van der Zhan, M. (2010). Local governments, unexpected depreciation and financial performance adjustment. Financial Accountability & Management, 26(3), 299–324. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0408.2010.00503.x

- Pina, V., Arcas, M. J., & Marti, C. (2012). Accruals and ‘accounting numbers management’ in UK executive agencies. Public Money & Management, 32(4), 273–280. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540962.2012.691306

- Stalebrink, O. J. (2007). An investigation of discretionary accruals and surplus-deficit management: Evidence from Swedish municipalities. Financial Accountability & Management, 23(4), 441–458. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0408.2007.00437.x

- Watts, R. L., & Zimmerman, J. L. (1986). Positive accounting theory. Prentice-Hall.

- Zimmerman, J. (1977). The municipal accounting maze: An analysis of political incentive. Journal of Accounting Research, 15, 107–144. https://doi.org/10.2307/2490636