IMPACT

This article is aimed at policy-makers and contributes to the debate on the shift towards performance and non-financial auditing in public sector organizations. It offers useful insights that national regulators and standard setters can consider when introducing new rules and standards in the audit sphere. Regulators and standard setters interested in teasing out the professional support that auditors can offer need to be aware of the need to blend economic efficiency targets with more sophisticated and sometimes not quantifiable assessment methods on specific topics.

ABSTRACT

This article contributes to the debate on the emergence of performance and non-financial auditing in the public sector and covers a gap in the literature regarding supra-national audit institutions. The authors investigate whether the European Court of Auditors’ audit methods are aligned with the different public sector paradigms (Public Administration, New Public Management and New Public Governance) using institutional logics perspectives: bureaucratic logic, managerial logic and public value logic. Their results confirm that performance auditing has led to ECA focusing on non-financial issues.

Introduction

The European Court of Auditors (ECA), the guardian of European Union (EU) finances, is going through a process of transformation intended to address current public concerns, such as climate change, the rule of law and the EU welfare system’s sustainability (Wolff & Ladi, Citation2020), as well as recent changes in the audit profession—now deeply affected by digital transformation.

The ECA’s methodology has been shifting in focus from a ‘financial and compliance audit’ towards a more ‘performance audit oriented’ approach. The ECA intends to enhance its activity with added value, focusing on performance, and producing clearer messages for EU citizens and decision-makers, to ensure that public funds are spent thoughtfully, and scrutinizing matters of pressing interest. While the ECA’s initial strategy followed a New Public Management (NPM) approach, the more recent one brings a more public value-oriented approach, aligned with New Public Governance (NPG) (Osborne, Citation2006; Almqvist et al., Citation2013).

This article connects public sector auditing to the different institutional logics related to three public sector paradigms: Public Administration (PA), NPM and NPG. Additionally, we evidence that the evolution of the ECA audit methodology and standards contributed to the overall improvement of the audit process over time. Hence, this article demonstrates a shift in the ECA’s focus towards financial performance, i.e. looking into the evaluation of the effectiveness, efficiency and economy (3Es) of EU actions. In performance auditing, the ECA has given increasing attention to non-financial issues, such as sustainability and the environment, governance, transparency, rule of law, fraud and corruption and other social issues, seeking to reinforce transparency as a public value from the NPG perspective.

Institutional logics of public sector paradigms and public sector auditing

The institutional logics perspective offers a lens which helps understand organizational transformation triggered by the actors’ actions and the internal and external environmental evolution (Battilana, Citation2006; Friedland & Alford, Citation1991). The institutional logics approach provides guidelines to understand how actors and organizations behave in specific environments and situations, given the often co-existing and competing logics within institutions (Lounsbury, Citation2007).

Institutional logics informs organizational behaviour and evolution through the collective identification of a group, by means of the cognitive, emotional and normative connection of individuals with their peers, aiming to acquire a certain social or professional status and category (Thornton & Ocasio, Citation2008). Institutional logics influences the prioritization of issues to be attended to, based on sets of rules which determine their relevance and legitimacy, mostly centred on the prevailing logics (Thornton, Citation2002). Thus, any organization may be analysed from an institutional logics perspective—the established rules, practices and ideas available to individuals and groups to help them shape their actions (Parker et al., Citation2021). Institutional logics is a proper theoretical framework for analysing the connections and influences of evolving institutional logics perspectives related to public sector paradigms on the evolution of public sector auditing.

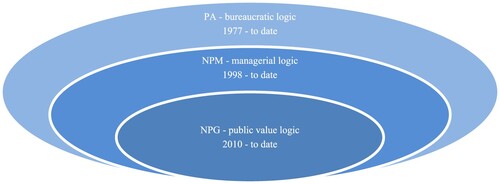

We analysed public audit from three institutional logics perspectives: the bureaucratic logic of PA, the business/managerial logic of NPM and the public value logic of NPG (see ). These three logics explain the evolution of the public auditors’ role from mere ‘books checkers’ and watchdogs under bureaucratic logic (Power, Citation1997; Gendron et al., Citation2001) to public sector performance scrutinizers, as performance audit became a crucial NPM component and, furthermore, to supervisors and advisors of the implementation of non-financial performance from an NPG paradigm.

Table 1. Institutional logics and roles of public sector auditors.

Public administration paradigm and compliance/financial auditing

First, from the PA perspective, bureaucratic logics were dominant after the Second World War, and up to the 1980s, in policy design and implementation. The PA’s Weberian model (Meyer et al., Citation2014) is based on the prevailing rule of law, with a strict normative application, based on rationality, a central place for policy-makers, increasing budgets seeking to provide solid welfare systems and solid public services as social advancements, with the increasing professionalization of public services and a clear hierarchy and merit-based personnel selection (Osborne, Citation2006). This is time coincidental with the generalization of financial and compliance audit procedures in the public sector—focused on inputs and regulations—seeking to ensure bureaucratic accountability by scrutinizing the more formal aspects of policy and budget implementation. It does not represent an evaluation of public management performance (Power, Citation1997) but a strictly procedural process, sometimes considered too resource-consuming and ineffective. At that point, at both the private and public level, audit was seen as a formal requirement of activity oversight, performed in a fairly unstructured fashion based on an auditor’s individual judgment (Dirsmith & McAllister, Citation1982).

The ECA’s methods developed in line with the evolution of the audit methodology and standards, and a first Audit Manual was issued in 1990. A turning point was the introduction in 1994 of the Statement of Assurance (in French the Déclaration d’Assurance, or DAS): the equivalent of the audit opinion, updated with an assurance model in 2005, which seeks to confirm the true and fair image of the EU accounts, as well as the legality and regularity of their implementation, based on a bureaucratic logic. The ECA bases its audit task, among others, on the International Standards for Supreme Audit Institutions (ISSAIs) issued by INTOSAI and the International Standards on Assurance Engagements (ISAE) issued by the International Federation of Accountants (IFAC). In 1997, the ECA adopted the Court Audit Policy and Standards (CAPS). CAPS summarised the INTOSAI and IFAC standards and integrated the ECA’s audit policy. The DAS methodology, together with CAPS, allowed for more systematic financial and compliance audit procedures. This contributed to a more efficient use of the ECA’s resources, implementing a risk-based approach and therefore focusing its financial and compliance procedures on the most problematic areas of the EU budget.

The NPM paradigm and performance auditing

From the late 1970s and early 1980s, NPM was applied, based on the controversial belief that private sector management strategies and techniques could be suitable for the public sector, in an attempt to improve the performance and efficiency of public resources (Dunleavy & Hood, Citation1994). Thus, the PA focus based on the described bureaucratic logics—considered to be inflexible and resource consuming—shifted towards a business/managerial logic based on implementing private sector management processes. Policy-makers were no longer involved in policy implementation, and an entrepreneurial approach to public management was adopted, regarding citizens as customers and focusing on output, cost and performance management control and evaluation (Osborne, Citation2006), key performance indicators and benchmarking (Pollitt et al., Citation2007). Compliance with rules, regulations and established procedures was no longer in focus, and the private sector inspired a reward-based goal achievement system for public managers. Isolating public services from public oversight, public–private partnerships and the outsourcing of public services to the private sector were considered more efficient to manage resources and deliver improved services at a lower cost, and the concept of ‘value for money’ (VFM) was born (Pollitt et al., Citation2007).

Given its failure to generally demonstrate an improvement in public services or a more cost-efficient manner of public management, NPM was questioned by academia after 2000. Society then started experiencing what Power (Citation1997) named ‘the audit explosion’ as a benchmark for accountability, with auditors becoming indispensable in overseeing the financial and legal compliance of private companies and public organizations, because of higher scrutiny from regulators and a growing need for public servants and decision-makers to fulfil accountability requirements and legitimacy needs.

Hence, public institutions are expected to manage public finances in accordance with the principles of efficiency, effectiveness and economy—the 3Es—and their performance is mostly scrutinized through the performance audit (Cordery & Hay, Citation2019), a product of the managerial logic of NPM () and an essential component of the public accountability process (Power, Citation1997). Under the NPM paradigm, performance audit measures public actions’ efficiency and effectiveness (Almqvist et al., Citation2013) and also the adequacy of policy design and its compliance—substance over form—and non-financial aspects of budget and policy: the establishment of policy goals and objectives versus their realization. In some cases, audit institutions carrying out performance audits in NPM-oriented systems fall short of criticising the performance of political decision-makers and public management when needed. Furthermore, they are also unable to ensure that the performance audit has a positive influence on public action (Reichborn-Kjennerud, Citation2014).

The ECA Audit Manual later included performance-related modules, as performance started acquiring importance within the auditors’ task, given the managerial logic predominant within the EU institutions. The DAS methodology and CAPS allow for less resource-consuming audit procedures. Subsequently, the ECA issued the Performance Audit Manual, reinforcing the VFM principle, focusing on cost efficiency and financial savings, following NPM guidelines and reinforcing its managerial logic. Also, starting 2010, the ECA included a specific performance chapter in the financial and compliance audit report of the EU budget, called ‘Getting results from the EU budget’. For the 2019 financial and compliance audit, the ECA issued a separate accompanying annual report, called ‘Report of the ECA on the performance of the EU budget’, emphasizing its coexisting bureaucratic and managerial logics. The ECA emphasises the performance audit task, in its Strategy 2018–2020, stating that stakeholders expect confirmation that EU actions’ implementation achieved its intended results.

Public governance paradigm and non-financial auditing

In the late 1990s, there was a shift towards a public value logic and a quest to overcome the insufficiencies and shortcomings of the two previously mentioned models, by placing public and democratic values as central issues of public actions, and citizens, businesses and non-for-profit organizations as participants in designing and enforcing public policies (Bryson et al., Citation2014). Public value is seen as either the benefits for the public/citizens (Moore, Citation1995) or the consensus about the rights and obligations of the citizens and of the state to one another and the generally accepted principles for public policy and public governance.

While not a new concept (Osborne, Citation2006), NPG focuses on pursuing the public interest and providing public services, and it walks away from the ‘citizen as customer’ approach of NPM (Almqvist et al., Citation2013). The implementation of new ways of public management and governance has been rather hybrid, often overlapping and always developing, with the state regaining some control over the public action (Grossi & Argento, Citation2022; Uman et al., Citation2022).

A step further in strengthening the coexisting logics (managerial and public value) is the ECA’s Strategy 2021–2025, which underlines the intention to focus its performance audits on topics which add most value to society, such as freedom, democracy and rule of law, combatting fraud and corruption, climate change and the environment. These objectives can be assessed more easily from an impact viewpoint than the traditional efficiency/economy approach of performance audits. They are often of non-financial nature, enhancing the institution’s role in overseeing essential social pressing matters with a public value-added logic, following the PNG perspective. Hence, we conclude that the ECA has adapted its methodology to the different institutional logics related to public sector paradigms (PA, NPM and NPG), and coexisting logics appear and persist from its foundation until today.

Concluding discussion

This article contributes to the debate on the emergence of performance and non-financial auditing in the public sector and covers a gap in the literature regarding supra-national audit institutions (Bonollo, Citation2019; Mattei et al., Citation2021; Nerantzidis et al., Citation2022).

Together with financial audits, the ECA’s compliance audits focus on EU legislative and policy conformity, from a PA bureaucratic perspective. However, while performance auditing in the public sector (booming in recent decades, along with the adoption of NPM managerial logics) assesses financial performance, it also covers non-financial aspects such as the environment, corruption or fraud, immigration, rule of law, education or welfare services, more aligned with the NPG’s public value logic. These issues are more a matter of public social value than efficiency and often cannot be quantified—requiring a more elaborate and qualitative assessment framework. This new function seeks to gain public auditors’ recognition as more than balance sheet checkers and to demonstrate their relevance (Hay & Cordery, Citation2021).

While we could establish a longitudinal evolution of the ECA’s task, in line with our institutional logics framework (), it is also apparent that the ECA operates with coexisting logics. These logics imply that the institution is influenced by environmental, political, professional and social factors and adapts its activity to the dominant public management approach. This is evident because, while improving and systematizing its financial and compliance audits, the ECA has continued to conduct them, producing relevant new audit observations and a follow up of previous recommendations, underpinning its bureaucratic logic (Power, Citation1997). Also, while increasing their non-financial audit outputs, thus reinforcing their public value logic, the auditors have continued to follow the VFM principle, giving recommendations on the EU’s financial management through financial savings and more cost-efficient methods, following NPM guidelines embedded in their managerial logic.

Once we determined the coexistence of institutional logics, these could also be seen as blending or layering institutional logics (Polzer et al., Citation2016), that is adopting a different institutional logic as an additional layer of logics, without abandoning the previous one, as the ECA did ().

These institutional logics will likely coexist and be layered in the future, especially given the public landscape created by the Covid 19 pandemic, with the consequent adoption of the NextGenerationEU programme, the largest EU stimulus package ever. This programme’s implementation raises doubts and complications and will need a strong external oversight, reinventing ECA’s role as a key accountability player, especially in a period of uncertainty.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Almqvist, R., Grossi, G., van Helden, J., & Reichard, C. (2013). Public sector governance and accountability. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 24(7-8), 479–487. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpa.2012.11.005

- Battilana, J. (2006). Agency and institutions: The ‘enabling role of individuals’ social position. Organization, 13(5), 653–676. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350508406067008

- Bonollo, E. (2019). Measuring supreme audit institutions’ outcomes: Current literature and future insights. Public Money & Management, 39(7), 468–477. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540962.2019.1583887

- Bryson, J. M., Crosby, B. C., & Bloomberg, L. (2014). Public value governance: Moving beyond traditional public administration and the new public management. Public Administration Review, 74(4), 445–456. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.12238

- Cordery, C. J., & Hay, D. (2019). Supreme audit institutions and public value: Demonstrating relevance. Financial Accounting & Management, 35, 128–142. https://doi.org/10.1111/faam.12185

- Dirsmith, M. W., & McAllister, J. P. (1982). The organic vs. the mechanistic audit. Journal of Accounting, Auditing and Finance, 5(3), 214–228.

- Dunleavy, P., & Hood, C. (1994). From old public administration to new public management. Public Money & Management, 14(3), 9–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540969409387823

- Friedland, R., & Alford, R. R. (1991). Bringing society back in: Symbols, practices, and institutional contradictions. In W. W. Powell, & P. J. DiMaggio (Eds.), The new institutionalism in organizational analysis (pp. 232–263). University of Chicago Press.

- Gendron, Y., Cooper, D. J., & Townley, B. (2001). In the name of accountability: State auditing, independence and new public management. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 14(3), 278–310. https://doi.org/10.1108/EUM0000000005518

- Grossi, G., & Argento, D. (2022). The fate of accounting for public governance development. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 35(9), 272–303. https://doi.org/10.1108/AAAJ-11-2020-5001

- Hay, D., & Cordery, C. J. (2021). Evidence about the value of financial statement audit in the public sector. Public Money & Management, 41(4), 304–314. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540962.2020.1729532

- Lounsbury, M. (2007). A tale of two cities: Competing logics and practice variation in the professionalizing of mutual funds. Academy of Management Journal, 50(2), 289–307. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2007.24634436

- Mattei, G., Grossi, G., & Guthrie, J. (2021). Exploring past and future trends in public sector auditing research: a literature review. Meditari Accountancy Research, 29(7), 94–134. https://doi.org/10.1108/MEDAR-09-2020-1008

- Meyer, R. E., Egger-Peitler, I., Höllerer, M. A., & Hammerschmid, G. (2014). Of bureaucrats and passionate public managers: Institutional logics, executive identities, and public service motivation. Public Administration, 92(4), 861–885. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9299.2012.02105.x

- Moore, M. H. (1995). Creating public value: Strategic management in government. Harvard University Press.

- Nerantzidis, M., Pazarskis, M., Drogalas, G., & Galanis, S. (2022). Internal auditing in the public sector: a systematic literature review and future research agenda. Journal of Public Budgeting, Accounting & Financial Management, 34(2), 189–209. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPBAFM-02-2020-0015

- Osborne, S. P. (2006). The new public governance? Public Management Review, 8(3), 377–387. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719030600853022

- Parker, L. D., Schmitz, J., & Jacobs, K. (2021). Auditor and auditee engagement with public sector performance audit: An institutional logics perspective. Financial Accountability & Management, 37(2), 142–162. https://doi.org/10.1111/faam.12243

- Pollitt, C., Van Thiel, S., & Homburg, V.2007). New public management in Europe. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Polzer, T., Meyer, R. E., Höllerer, M. A., & Seiwald, J. (2016). Institutional hybridity in public sector reform: Replacement, blending, or layering of administrative paradigms. In How institutions matter! Emerald. https://www.emerald.com/insight/publication/doi/10.1108S0733-558X201748B

- Power, M. (1997). The audit society: Rituals of verification. Oxford University Press.

- Reichborn-Kjennerud, K. (2014). Performance audit and the importance of the public debate. Evaluation, 20(3), 368–385. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356389014539869

- Thornton, P. H. (2002). The rise of the corporation in a craft industry: Conflict and conformity in institutional logics. Academy of Management Journal, 45(1), 81–101. https://doi.org/10.5465/3069286

- Thornton, P. H., & Ocasio, W. (2008). Institutional logics. In R. Greenwood, C. Oliver, R. Suddaby, & K. Sahlin-Andersson (Eds.), The Sage handbook of organizational institutionalism (pp. 99–128). Sage.

- Uman, T., Argento, D., Mattei, G., & Grossi, G. (2022). Actorhood of the European Court of Auditors: a visual analysis. Journal of Public Budgeting, Accounting & Financial Management, https://doi.org/10.1108/JPBAFM-08-2021-0130

- Wolff, S., & Ladi, S. (2020). European Union responses to the Covid-19 pandemic: Adaptability in times of permanent emergency. Journal of European Integration, 42(8), 1025–1040. https://doi.org/10.1080/07036337.2020.1853120