ABSTRACT

This article focuses on those organizational and individual factors that increase public managers’ belief in their proactive ability to pursue collective implementation of digital public services. Using social cognitive theory, the authors show that managers’ innovation-implementation efficacy is shaped within the context of the current massive digital transformation of public services. The study uncovers two organizational enablers (organizational climate for innovation and leader expectations for creativity), together with two individual enablers (creative self-efficacy and proactive behaviour). The findings suggest that creative self-efficacy partly mediates between an organizational climate for innovation and collective implementation efficacy. Additionally, leaders’ expectations for creativity and proactivity were found to be partly mediated between innovative climate and collective implementation efficacy.

IMPACT

Following the global massive digital government framework, this article (based on the Digital Israel case) provides relevant lessons and directions for managerial practice. Following the notion that collective human perceptions at work have an impact on successful implementation of technology and digitalization, the authors highlight the mechanisms, at the micro-managerial level, that support public managers’ collective capability to implement innovative digital services efficiently. The research model can be used to design HRM strategies to promote managers’ proactive behaviour—a key determinant of managers’ collective implementation efficacy during the digital innovation processes. Practically, a manager’s proactive behaviour, shaped through a climate of innovation and creative self-efficacy, can promote collective confidence in implementing digital services and innovations.

Introduction

Following the OECD recommendation to actualize the ‘digital government’ concept, most member countries are embracing emerging technologies (OECD, Citation2017). The increasing pressure from politicians and citizens on public agencies and their employees to innovate (Barrutia & Echebarria, Citation2019) is producing a need for more highly skilled and motivated employees who will be able to implement new digital services efficiently. This process will likely continue, because each wave of digital technology raises new problems for implementation (Wilson & Mergel, Citation2022) and studies examining the factors supporting the implementation of digital public services are constantly needed. The current study focuses on the micro-managerial level in this evolving context, and investigates the mechanisms supporting public managers’ collective capability to implement innovative digital services.

Previous studies indicate that implementing innovation is extremely challenging, since such innovations exist in individual, organizational, national, and international contexts (Demircioglu & Audretsch, Citation2017). Therefore, it is strongly recommended that public sector researchers focus more on organizational and contextual factors affecting public sector innovation (Demircioglu, Citation2020). One important research limitation is that studies typically do not devote sufficient attention to analysing the role of individual and contextual variables in innovation implementations (Choi & Chang, Citation2009; Piening, Citation2011). Understanding the factors that maximize the innovation implementation phase among public managers who deploy new digital services will be of enormous benefit.

In line with the idea that collective human perceptions have an impact on successful implementation of technology (Holahan et al., Citation2004; Siddiq et al., Citation2017) our study focused on the collective unit of implementation. Considering that successful implementation of innovation requires collective and co-ordinated action among employees (Choi & Chang, Citation2009), we explored the mechanism that supports the collective processes that represent shared and aggregated patterns of beliefs and behaviour of public servants in the innovation implementation stage. As suggested, individuals are not autonomous in adopting and implementing the innovation (Holahan et al., Citation2004) and the provision of digital services depends on professional public officials possess the right skills but also are able to collaborate effectively when implementing innovation (‘collective efficacy’: see Chung & Choi, Citation2018). The extent to which an employee can benefit from new technological practices and services largely depends on the concurrent actions of interdependent others (Choi & Chang, Citation2009; Holahan et al., Citation2004). Our study relied on Choi and Chang (Citation2009) who were the first to focus attention on collective implementation efficacy as it affects employees’ collective acceptance of innovation within the e-government context. Also, we took into account studies that have shown that collective efficacy influences behaviour and positively shapes experiences through self-actualizing predictive loops (Donohoo & Katz, Citation2019). Although collective efficacy is recognized as a key variable for predicting creative and innovation performance (Choi & Chang, Citation2009; Liu et al., Citation2015), the question how exactly a sense of collective implementation efficacy forms remains largely unaddressed, particularly in the public management literature. The current study addresses this gap. Our research question was:

What are the antecedents which amplify public managers’ collective implementation efficacy as they actualize new public services?

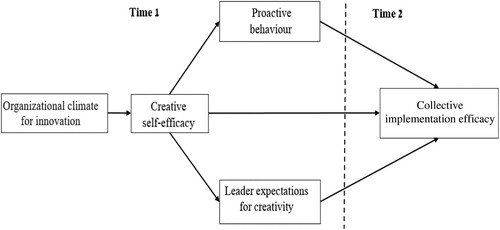

To develop a response to the research question, our theoretical model examined the antecedents of public managers’ collective implementation efficacy by offering a framework of the mediating role of three variables—two individual enablers: creative self-efficacy and proactive behaviour, and one organizational enabler: leader expectations for creativity—as constituting a link between organizational climate for innovation and collective implementation efficacy (see ). Various researchers looking at innovation have investigated these factors, but the present research has the advantage of testing all those factors in one model and among public managers who implement new digital services.

Explanatory mechanisms—both individual and collective—of innovation or creative production have been carried out in cognitive and social psychology (Dampérat et al., Citation2016). Accordingly, this study employs social cognitive theory, which is grounded in the agentic perspective (Bandura, Citation2001), to explore the mechanism of managers’ creative self-efficacy and collective implementation efficacy within the public sector innovation context.

This article provides major contributions to the existing literature on innovation implementation in the public sector. First, our findings contribute to the knowledge of public sector innovation implementation at the micro-managerial level. Despite governmental strategy promoting recent OECD recommendations reinforcing institutional capacities to manage project implementation within the digital government reform (OECD, Citation2022), there remain glaring empirical and pragmatic deficits in our understanding of the individual-organizational mechanism supporting a manager's perceptions regarding innovation implementation of digital public services. Second, despite overwhelming scholarly consensus maintaining that frontline managers are key to facilitating service innovation (Gallup Organization, Citation2011), only limited attention has been paid to explaining innovation from managers’ points of view (Shanker et al., Citation2017). This study focuses on public sector line managers tasked with innovation implementation and whose performance is critical to their organization and to service delivery (Plimmer et al., Citation2022). Our practical perspective offers novel empirical knowledge regarding this lacuna at the managerial level the policy level, with several concrete implications for practitioners. While we still face repercussions from the Covid 19 pandemic, policy-makers should develop a broad understanding of the various factors supporting successful implementation of service innovation within the recent massive digital government framework.

Theoretical background and hypotheses

Theoretical foundations

Social cognitive theory (Bandura, Citation2002), grounded in the agentic perspective, suggests that individuals hold certain beliefs about their ability to realize and implement innovation through their own actions (Ng & Lucianetti, Citation2016). The study is underpinned by the notion that the diffusion of an innovation can be seen as a process in which ‘an innovation is communicated through certain channels over time among the members of a social system’ (Rogers, Citation2003, p. 5). Since successful functioning requires an agentic blend of three modes of agency—direct personal, proxy and collective (Bandura, Citation2002, p. 270), we assumed that successful innovation implementation necessitates individuals’ self- and collective efficacy to actualize innovation among these modes. The basis for this assumption derives from the idea that although beliefs in collective efficacy have a socio-centric focus, the functions they serve are similar to those of personal efficacy beliefs and they operate through similar processes (Bandura, Citation1997). Considering that innovation implementation can be explained as a socially-constructed process constituted ‘in interaction with others’ (Chung & Choi, Citation2018; Cohen et al., Citation2004), the study concentrates on the factor concerned with collective implementation efficacy.

Managers’ perception of collective implementation efficacy

Scholars have underscored collective efficacy as a ‘key social cognitive element that may help to explain how groups function together’ (Lent et al., Citation2006). Collective efficacy is critical to predicting a wide array of team behaviour and effectiveness. Locke (Citation1991) theorized that collective efficacy, in conjunction with team goals, constitutes the ‘motivational hub’, which represents the processes that most directly affect action. Specific to the work-related innovation context, collective efficacy can motivate two major sets of behavioural tasks—idea generation and idea implementation, which result in innovation performance. A high level of collective efficacy has been positively associated with innovation performance and successful implementation (Liu et al., Citation2015). When employees believe that they already have the skills or resources needed to implement an innovation (high implementation efficacy), they can easily incorporate it into their related innovation tasks (Choi & Moon, Citation2013).

Efficacy belief is dependent on actual competence and is a situation-specific judgement based on the resources, opportunities, and constraints present in a given setting (Choi et al., Citation2003). In this respect, the literature finds two complementary factors shaping innovation implementation—the organizational members who put it into practice and the social organizational context constituting this interaction between the innovation and organizational members (Choi & Moon, Citation2013; Choi & Chang, Citation2009; Klein & Knight, Citation2005). Thus, we suggest that organizational members may estimate their implementation efficacy by assessing how much personal and situational resources (or constraints) are present relative to the innovation to be implemented.

Organizational climate for innovation and collective implementation efficacy

The internal environment supportive of innovation defined as an ‘organizational climate for innovation’ (OCI) (Shanker et al., Citation2017), can have a positive effect on individuals’ creativity and innovation in the workplace. Scholars suggest that the extent to which the values and norms of an organization emphasize innovation can have a vital role in leveraging individuals’ innovative work behaviour (Anderson et al., Citation2014; Park & Jo, Citation2018; Scott & Bruce, Citation1994; Shanker et al., Citation2017). It has been suggested that ‘when a unit’s climate for innovation implementation is strong and positive, employees regard innovation use as a top priority, not as a distraction from or obstacle to the performance of their real work’ (Klein & Knight, Citation2005, p. 245). Within an organizational climate for innovation where creativity and change are encouraged and employees can share and build upon each other's ideas and suggestions (Isaksen & Ekvall, Citation2010), they will likely believe in their personal and collective capability to implement the innovation. Those theoretical and empirically-based arguments collectively support our claim that OCI may be considered one antecedent of individual perception of collective efficacy within the innovation implementation stage:

H1: OCI is positively related to collective implementation efficacy.

The mediating role of creative self-efficacy

Creative self-efficacy was a core topic in the research model as it refers to an individual's perception that they are capable of achieving creative and innovative outcomes (Tierney & Farmer, Citation2002; Newman et al., Citation2018). Based on Bandura's general definition of self-efficacy, Tierney and Farmer (Citation2002) defined creative self-efficacy as ‘the belief one has the ability to produce creative outcomes’ (p. 1138). The social cognitive theory proposition that self-efficacy plays a motivational role in the process of creativity and innovation (Bandura, Citation1997) encourages researchers to examine its antecedents and consequences in workplace innovation. Scholars have suggested that, in the workplace, individuals are much more likely to engage in tasks if they assume they will accomplish something and if they regard themselves as potentially successful (Haase et al., Citation2018). Specific to innovative work behaviour and implementation-oriented behaviour, studies have found that:

Employees with a high level of creative self-efficacy likely possess confidence in their knowledge and skills to generate ideas and implement those ideas at work (Jiang & Gu, Citation2017).

These employees are also likely to feel better equipped to address the challenges and uncertainty faced when developing and implementing new ideas in the workplace (Richter et al., Citation2012).

Considering that efficacy beliefs do not exist in isolation (Bandura, Citation1997), we suggest that, within the ‘digital government’ context, the organizational climate for innovation likely influences individuals’ creative self-efficacy. This means that managers who perceive an organizational climate promoting innovation, and supporting the implementation of novel tools, technologies or services, are likely to display a high level of creative self-efficacy. This assumption derives from previous studies suggesting that organizational antecedents (such as group norms and organizational support) may influence creative self-efficacy (Puente-Díaz, Citation2016). Jaiswal and Dhar (Citation2015) found that the degree of an individual's belief about their creative capability is easily affected by such contextual factors as innovation climate. Therefore, our second hypothesis was:

H2: OCI is positively related to managers’ creative self-efficacy.

We then wondered if a climate for innovation enhances individual creative self-efficacy beliefs, which, in turn, function as a key driver in forming their perception of collective implementation efficacy. This idea is based on the positive influence of self-efficacy on collective efficacy (Borgogni et al., Citation2010; Gibson & Earley, Citation2007; Fernández-Ballesteros et al., Citation2002) and on studies which found that creative self-efficacy serves as a promising mediator between contextual and individual factors and employee creative performance (for example Gong et al., Citation2009; Puente-Díaz, Citation2016). Since efficacy beliefs nourish intrinsic motivation by enhancing perceptions of self-competence (Bandura, Citation1997) creative self-efficacy may also reflect intrinsic motivation to engage in innovation and creativity activities (Gong et al., Citation2009). A study with R&D employees found that the positive influence of self-expectations on creative performance was mediated by creative self-efficacy (Tierney & Farmer, Citation2004). Echoing a similar view, our assumption was that OCI likely affects creative self-efficacy, and this in turn influences innovation implementation efficacy:

H3: Creative self-efficacy will mediate the relationship between OCI and collective implementation efficacy.

The mediating role of leader expectations for creativity

Top management plays a critical role in encouraging employees to implement creativity and innovation work behaviour (Carmeli & Paulus, Citation2015; Tierney & Farmer, Citation2002). Hence, leader expectations for creativity are necessary to motivate subordinates to engage in creative courses of action in the workplace (Qu et al., Citation2015). Scholars have devoted close attention to the role of leadership expectations for creativity and ways in which leaders may use persuasion and other influence tactics to enhance subordinates’ workplace creativity (Carmeli & Schaubroeck, Citation2007; Jiang & Gu, Citation2017).

Tierney and Farmer’s (Citation2002) study of the ‘Pygmalion’ process within employee creativity found that supervisors holding higher expectations for employee creativity were perceived by employees as behaving more supportively. Individuals who display high levels of creative self-efficacy are more likely to consider top management’s creativity expectations, stimulating them to perceive both their leaders and organizations as encouraging and facilitating collective implementation efforts (Scott & Bruce, Citation1994). So, when line managers recognize that the organizational climate supports innovation, this climate will likely increase their creative self-efficacy which, in turn, increases their perception of leaders’ expectations for creativity, thus enhancing their collective implementation efficacy:

H4: Leader expectations for creativity will mediate the relationship between OCI and creative self-efficacy and collective implementation efficacy.

The mediating role of proactive behaviour

A proactive personality is a key determinant of commensurate proactive behaviour influencing creativity and innovation (Parker et al., Citation2010; Scott & Bruce, Citation1994). Crant (Citation2000, p. 436) defines proactive behaviour as ‘taking initiative in improving current circumstances or creating new ones; it involves challenging the status quo rather than passively adapting to present conditions’. Proactive behaviour, through two of its characteristics—acting in advance and intended impact—is enhanced especially through pressure for innovation (Grant & Ashford, Citation2008). We propose that an individual's proactive personality mediates the relationship between organizational climate for innovation and an individual's creative self-efficacy and collective implementation efficacy. We base this assumption on studies that have investigated proactivity as a mediator (Belschak & Den Hartog, Citation2010; Park & Jo, Citation2018). These studies found that team perception of organizational climate for innovation has a positive and significant cross-level effect on individual proactive attitudes (Magni et al., Citation2018). In this context, managers who recognize that the organizational climate supports innovation are likely to display a high level of creative self-efficacy, which in turn increases their own proactivity (Den Hartog & Belschak, Citation2012; Griffin et al., Citation2010; Huang, Citation2017). One should keep in mind that the linkage between proactive behaviour and performance evaluations is stronger when leaders themselves possess proactive temperaments than when they display passivity (Fuller et al., Citation2012). When individuals display proactive behaviour they seize the initiative in improving current circumstances or creating new ones (Crant, Citation2000). It is also worth noting that proactive advancement efforts have been found to be a major contributor towards the overall accomplishments of innovation projects (Bjorklund et al., Citation2013). Proactive personality is most frequently investigated in studying work performance (Parker et al., Citation2010) and innovative work behaviour, yet little consideration has been given to an examination of the ways public officials’ proactive personality affects their innovative work behaviour (Suseno et al., Citation2020) and, in particular how it influences their collective implementation efficacy. This led us to our fifth research hypothesis:

H5: Proactive behaviour will mediate the relationship between OCI and creative self-efficacy and collective implementation efficacy.

Rationale

This study has been framed within the context of public sector digital innovation to understand managers’ behaviour and perceptions within digital innovation of the public services. Following OECD recommendations for the Israeli economy, and highly influenced by the OECD agenda demanding fast-tracking of digital transformation of public services which stress increased adoption of innovation and enhanced access to public services, Israel established the National Digital Program in 2017 (Digital Israel National Initiative, Citation2017). Since then, most public sector organizations and their employees have been involved in a digital transformation directed at promoting economic prosperity, social equality and smart government. Therefore, managers who have participated in the National Digital Program are a highly appropriate ‘target population’ and should provide relevant information regarding the actual experience of implementation of service innovation by digital means.

Method

Sample and procedure

Our first procedural step was to conduct a pilot questionnaire with a sample of 30 adult students working in the public sector target population. The pilot stage instrument was pre-tested with a sampling of 30 academics and public sector officers to ensure against ambiguity in the questions. This stage identified any potential problems with the questionnaire (Dillman et al., Citation2009). Thus, the clarity and relevance of the questions to participants was ensured. A moderately sized sample on a targeted population, for instance on 30 to 50 respondents, has been found acceptable as a preliminary study (Slavec & Drnovšek, Citation2012). Data collected from this pilot test were reviewed and minor modifications made.

In the second step, data were collected using an internet-based survey administered by means of the iPanel: an Israeli public opinion institute with over 100,000 members. IPanel adheres to the most stringent ESOMAR criteria and since 2006 has provided an online platform for a wide variety of information collection services, including polls and public opinion surveys. By conducting sample designed to represented the Israeli population in most dimensions all ethics requirements were assured as well as the anonymity of all participants.

Precautions on two issues were taken. First, to reduce the potential influence of common method bias that may occur when the predictor and criterion variables are measured at the same time (Podsakoff et al., Citation2012), the survey was administered in two waves within a period of two months. In longitudinal design in public management studies, when the unit of analysis is at the individual level, two-wave studies are a common strategy (Jacobsen & Andersen, Citation2014) and can be considered as longitudinal (Stritch, Citation2017). Longitudinal research examining individual-level public employee phenomena is still limited both in the quantity of published research and the topics considered (Stritch, Citation2017). Short distances in time between waves were chosen to obviate the possibility of participants’ life circumstances changing in significant ways (Carmeli & Spreitzer, Citation2009). Second, the question of who should evaluate the implementation of innovation requires an explanation. Research has mainly been concerned with assessing the innovative and creative behaviour of employees, whether their managers have assessed them or through objective measures, or finally through self-assessment (Puente-Díaz, Citation2016). The question of self-evaluation of innovative behaviour has been raised in previous studies (Janssen, Citation2005; Madrid et al., Citation2014). Prior empirical studies found that self-reporting of creativity correlates with supervisory ratings (Axtell et al., Citation2000). In this study, managers assessed collective implementation efficacy via a self-reported measure, with the assumption that they are well aware of their work environment and their actions.

In the first wave of data collection, a total of 550 complete responses was obtained from managers in the public sector (an 82.3% response rate). In the second wave, 303 complete responses (a 55.09% response rate) were obtained. Pairing the respondents between the two waves provided complete data for 298 participants, corresponding to a total response rate of 54.18%. Respondents were categorized as belonging to one of several types of government organizations: 46% work at authorities and institutions providing public service, 29% at government service offices and 25% at local government authorities. Of these, 177 were women (60%) and 121 were men (40%). The majority of the respondents had an academic degree (72%); 60% were middle managers and 40% were team leaders.

Measures

The proposed scales were adapted from prior relevant literature. The survey was initially created in English and then translated into Hebrew. We followed McGorry's (Citation2000) procedures to ensure the accuracy of the original scales and items:

Organizational climate for innovation was measured by a six-item scale developed by Kang et al. (Citation2016). Responses were on a five-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree (α = 0.78).

Proactive behaviour was measured by an 11-item scale developed by Belschak and Den Hartog (Citation2010). The questionnaire is comprised of three subscales measuring different foci of proactive behaviours: organizational proactive behaviour; interpersonal proactive behaviour; and personal proactive behaviour. The results were rated on a seven-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 = very strongly disagree to 7 = very strongly agree (α = 0.92).

Creative self-efficacy was measured by a three-item scale developed by Tierney and Farmer (Citation2002). The results were rated on a six-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 = very strongly disagree to 6 = very strongly agree (α = 0.84).

Leader expectations for creativity was measured by a four-item scale developed by Farmer et al. (Citation2003) and modified by Carmeli and Schaubroeck (Citation2007). Responses were made on a five-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 = not at all to 5 = to a large extent (α = 0.83).

Collective implementation efficacy was measured by four-item scale developed by Choi and Chang (Citation2009). The results were rated on a five-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 = very strongly disagree to 5 = very strongly agree (α = 0.86).

Data was collected on relevant control variables which might influence innovativeness. We controlled for gender (1 = woman, 2 = man), number of years of job tenure, education (1 = elementary school, 2 = secondary school, 3 = post-secondary education, 4 = BA, 5 = MA., 6 = PhD) and age. These variables have been recognized in previous study as relating to innovative behaviour (Tierney & Farmer, Citation2004).

Results

displays means, standard deviations, and inter-correlations among research variables, and provides support for H1 and H2. All variables displayed good internal consistency, and had acceptable levels of coefficient alpha (α > 0.70) (Hair et al., Citation2014). Collinearity was tested before conducting the regression analysis, using variance inflation factors (VIFs) (see , and ). Since the tolerance level was greater than 0.10, multi-collinearity was ruled out (Hair et al., Citation2014).

Table 1. Means, standard deviations and correlations.

Table 2. Creative self-efficacy as a mediator of the organizational climate for innovation–collective implementation efficacy relationship.

H3, H4 and H5 were tested with the independent variable as well as the mediators at Time 1, and the dependent variable was measured at Time 2.

H3 predicted that creative self-efficacy would mediate the relationship between OCI and collective implementation efficacy. demonstrates a positive association between innovative climate and creative self-efficacy (β = 0.26, p < 0.01); between creative self-efficacy and collective implementation efficacy (β = 0.18, p < 0.05); and between OCI and collective implementation efficacy (β = 0.52, p < 0.001). Model d suggests that the effect of OCI on collective implementation efficacy decreased in absolute size (β = 0.50, p < 0.01) when controlling for the effect of creative self-efficacy, and therefore it partly mediated this relationship. Additionally, the final model also explained a reasonable variance in collective implementation efficacy (31%). Sobel (Citation1982) provided an approximate significance test for the indirect effect of the OCI on collective implementation efficacy via creative self-efficacy (Sobel test statistic = 1.87, p < 0.001). These findings partly confirm H3.

H4 predicted that leader expectations would mediate the relationship between OCI and creative self-efficacy and collective implementation efficacy. The results in reveal a positive association between OCI and leader expectations (β = 0.46, p < 0.001), between leader expectations and collective implementation efficacy (β = 0.31, p < 0.001), and between OCI and collective implementation efficacy (β = 0.50, p < 0.001). Model d suggests that the effect of OCI on collective implementation efficacy decreased in absolute size (β = 0.46, p < 0.001) when controlling for the effect of leader expectations, and therefore it partly mediated this relationship. The final model also explained a reasonable variance in collective implementation efficacy (32%). Sobel (Citation1982) provided an approximate significance test for the indirect effect of the OCI on the collective implementation efficacy via creative self-efficacy and leader expectations (Sobel test statistic = 2.98, p < 0.001). These findings partly confirmed H4.

Table 3. Results of examining leader expectations as a mediator of the organizational climate for innovation–collective implementation efficacy relationship.

H5 predicted that proactive behaviour would mediate the relationship between OCI and creative self-efficacy and collective implementation efficacy. The results in reveal a positive association between OCI and proactive behaviour (β = 0.54, p < 0.001), between proactive behaviour and collective implementation efficacy (β = 0.51, p < 0.001), between OCI and collective implementation efficacy (β = 0.50, p < 0.001). Model d suggests that the effect of OCI on collective implementation efficacy decreased in absolute size (β = 0.32, p < 0.001) when controlling for the effect of proactive behaviour, and therefore it partly mediated this relationship. The final model also explained a reasonable variance in collective implementation efficacy (37%). Sobel (Citation1982) provided an approximate significance test for the indirect effect of the OCI on the collective implementation efficacy via creative self-efficacy and leader expectations (Sobel test statistic = 2.17, p < 0.05). These findings partly confirmed H5.

Table 4. Results for examining proactive behaviour as a mediator of the organizational climate for innovation–collective implementation efficacy relationship.

Discussion and conclusions

The majority of our hypotheses about antecedents of managers’ collective implementation efficacy beliefs were supported by our data. The results provide several extensions to theory and research on collective implementation efficacy beliefs, with important implications for organizational and managerial practices.

Our research model delineating the effect of both contextual and individual antecedents on collective implementation efficacy yielded a number of helpful results. These effects have not been previously tested in the innovative behaviour literature. Digital innovation in the public sector is still in its early stages, and we have identified the factors that may affect its successful implementation of digital services. Consistent with our first two predictions, our findings reveal that managers’ perceptions of OCI play a role in determining their creative self-efficacy and collective implantation efficacy. Admittedly, the public sector is often characterized by a bureaucratic culture, and this makes innovation implementation a complex challenge. In this regard, Moldogaziev and Resh (Citation2016) have noted that ‘leadership in public bureaucracies may matter the most for successful implementation of adopted innovations through crafting better climates for innovations and allowing the employees greater discretion to be creative’ (p. 690). Therefore, the starting point must be determining whether public sector organizations have adopted a culture that creates an OCI.

This study reveals that OCI plays a pivotal role in enhancing both creative self-efficacy and collective implementation efficacy. Our findings support previous studies suggesting that an innovation climate constitutes an antecedent of innovative work behaviour (De Jong, Citation2006; Shanker et al., Citation2017). Further, effective leadership for innovation requires supporting such a proper climate and stimulating subordinates’ willingness to engage in creative processes (Carmeli & Schaubroeck, Citation2007). Additionally, regarding the third hypothesis, creative self-efficacy partly mediated the relationship between OCI and collective implementation efficacy. Namely, managers’ creative self-efficacy was a key driver in forming their perception of collective implementation efficacy. This finding confirms previous work stressing the positive influence of self-efficacy on collective efficacy (Borgogni et al., Citation2010; Gibson & Earley, Citation2007; Fernández-Ballesteros et al., Citation2002).

H4, predicting that leader expectations for creativity would mediate the relationship between OCI, creative self-efficacy and collective implementation efficacy was partly confirmed. In this respect, although middle managers might often have the best understanding of the need to innovate (OECD, Citation2017), innovation implementation will only bear fruit when organizational leadership has an expectation of creativity, as part of an all-sector policy. Signals originating with senior management are likely to be a particularly effective step forward toward innovation implementation (Choi & Moon, Citation2013), as management's support has been found to be a strengthening factor for collective implementation efficacy (Choi & Chang, Citation2009). These managerial perceptions may be consistent with Bandura's (Citation2002) suggestion that perceived collective efficacy bring the dynamics of group functioning to fruition.

Finally, findings concerning the fifth hypothesis, add to our existing knowledge the effect that proactive behaviour is partly mediated between creative self-efficacy and collective implementation efficacy. Our results corroborate previous studies’ findings that high self-efficacy in employees is positively correlated with proactive behaviour (Griffin et al., Citation2010; Huang, Citation2017). Our study shows that when line managers possess creative self-efficacy as well as proactive temperaments, collective implementation efficacy may be advanced. Proactive behaviour can be aimed at objectives aligned with prosocial organizational behaviour (Grant & Ashford, Citation2008; Griffin et al., Citation2010) and, as such, encourage collective implementation efficacy. Managers’ behaviour related to innovation is particularly influential in shaping related collective efficacy (Chen & Bliese, Citation2002). The findings show that expectations lead to actions through proactivity.

This study expands on social cognitive theory (Bandura, Citation2002) by offering an empirical model that simultaneously analyses both individual creative self-efficacy and collective efficacy during the innovation implementation phase. Organizational research has largely focused on outcomes of efficacy belief (Chen & Bliese, Citation2002), rather than on the factors responsible for the development of collective efficacy (Tasa et al., Citation2007). In this respect, the present study attempts a shift in direction to examine antecedents of collective implementation efficacy while including creative self-efficacy which has been found to be a key driver of employees’ innovative behaviour (Tierney & Farmer, Citation2002). The agentic perspective suggested in the current study, which is grounded in prior work indicating that when group members believe that they can achieve their goals as individuals they tend to feel more confident and make more effort to succeed collectively (Gibson & Earley, Citation2007), enriches the public management literature with the principles of social cognitive theory (Bandura, Citation2002). Our findings support the notion that successful innovation implementation necessitates individuals’ self- and collective efficacy to actualize innovation. The literature has demonstrated the positive influence of self-efficacy on collective efficacy (Borgogni et al., Citation2010; Fernández-Ballesteros et al., Citation2002) in a different organizational context than that of innovation implementation of digital services within the public sector. Therefore our proposed framework contributes to the public innovation literature by raising for discussion the enabling antecedents for implementation’s efficacy beliefs and their relationships. Despite its importance for achieving successful innovation and creativity processes, less empirical investigation has been devoted to understanding the phenomenon of implementation ideas (Mumford, Citation2003), in particular in the public management literature (Choi & Chang, Citation2009; Kim & Chung, Citation2017; Piening, Citation2011). By focusing on innovation implementations measurable at the individual level, our findings respond to researchers’ calls to extend the construct and to devoting more scientific attention to the ‘late cycle’ of idea implementation in the innovation process (De Jong & Den Hartog, Citation2008; Moldogaziev & Resh, Citation2016; Mumford, Citation2003).

Research limitations and directions for further research

Together with the interpretation of the findings and their contributions to the field, this study has some limitations. First, the study was solely conducted among managers in the public sector. Therefore, our results should only be generalized with context specificity in mind. However, this provides an opening to conduct similar studies in other sectors. One interesting extension of our work would be a comparison between sectors. Second, since the study population included only managers, it would be fruitful to cross-measure employees and managers—thus avoiding a potential common source bias. Employees may illuminate a different point of view about collective implementation efficacy, as well as the other topics analysed here. Third, the study was conducted in the specific contextual and cultural setting of Israeli organizations characterized by low power distance, a blend of individualism and collectivism, strong uncertainty avoidance and medium long-term orientation (https://www.hofstede-insights.com/product/compare-countries). Similar studies need to be conducted in other social and cultural settings before generalizability across different cultures can be claimed.

Implications for policy-makers and managerial practice

Our findings have implications for both policy-making and managerial practice. At the policy level, since there are various constraints to innovation implementation, policy-makers should prevent any additional potential contradiction within the internal organizational climate. An accelerated adoption of digitization in public services without the capacity to implement innovation exemplifies such a contradiction. Investment in training and equipping leaders with the skills they need to implement service innovation is of paramount importance. Once new digital services are adopted, it is the policy-makers’ responsibility to provide supportive, tailored programmes across the public sector organization, and to integrate training for managers leading them to create supportive organizational climate for public officials as they confront an innovation.

Considering the intensified digitalization of public administration which compels governments to ratchet up their provision of entirely novel services, which are both accurate and usefully up-to-date, it is therefore crucial to support those on the managerial level who have to deliver this process. Our research framework offers both personal and contextual topics that may well be useful in accomplishing the process of maximizing the value of digital services and the innovation process:

First, considering the positive influence of self-efficacy on collective efficacy and that both serve as key objectives in accomplishing the innovation tasks (Bandura, Citation2001; Dampérat et al., Citation2016; Ng & Lucianetti, Citation2016), organizations and public leaders should prioritize the agency perspective among public officials during the implementation of new digital services. Managers should energize subordinates to collaborate with colleagues to realize the intended benefits of new digital services for all stakeholders. It is important to note that ‘perceived collective efficacy is not simply the sum of the efficacy beliefs of individual members. Rather, it is an emergent group-level property that embodies the coordinative and interactive dynamics of group functioning’ (Bandura, Citation2002, p. 271).

Second, management’s expectation for creativity may encourage line managers’ potential to influence and promote innovation implementation.

Third, from a proactivity perspective, and considering that proactive behaviour encourages collective implementation efficacy, we suggest designing human resource practices that better identify proactive applicants in the recruitment and selection process of public managers. Practically, a manager’s proactive behaviour can be shaped through a climate for innovation and creative self-efficacy promoting collective confidence and a desire to implement digital services and innovation collectively. Our findings are applicable to lead HRM strategies oriented to sustain managers’ proactive behaviour as it is a key determinant of managers’ collective implementation efficacy during the digital innovation processes.

In sum, both policy-makers and HRM should consider that collective human perceptions at work have an impact on the successful implementation of technology and digitalization. In addition, frontline staff and middle managers often have the best understanding of the need to innovate (OECD, Citation2017) and of the factors that support collective implementation of innovative public services. Therefore, within the massive digitalization of public services and where the ‘adoption of the innovation requires targeted users undergo extensive, specialized training to learn the underlying principles of the innovation and overcome knowledge barriers to use’ (Holahan et al., Citation2004, p. 33), HRM should promote the skills and abilities required in managing and implementing digital innovation among mid-level executives and frontline managers.

Acknowledgements

The authors equally contributed to this paper. This research was supported by the committee of research and scientific activities of the Max Stern Yezreel Valley College.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Anderson, N., Potočnik, K., & Zhou, J. (2014). Innovation and creativity in organizations: A state-of-the-science review, prospective commentary, and guiding framework. Journal of Management, 40(5), 1297–1333.

- Axtell, C. M., Holman, D. J., Unsworth, K. L., Wall, T. D., Waterson, P. E., & Harrington, E. (2000). Shopfloor innovation: Facilitating the suggestion and implementation of ideas. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 73(3), 265–285.

- Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. Freeman.

- Bandura, A. (2001). The changing face of psychology at the dawning of a globalization era. Canadian Psychology/Psychologie Canadienne, 42(1), 12.

- Bandura, A. (2002). Social cognitive theory in cultural context. Applied Psychology, 51(2), 269–290.

- Barrutia, J. M., & Echebarria, C. (2019). Drivers of exploitative and explorative innovation in a collaborative public sector context. Public Management Review, 21(3), 446–472.

- Belschak, F. D., & Den Hartog, D. N. (2010). Pro-self, prosocial, and pro-organizational foci of proactive behaviour: Differential antecedents and consequences. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 83(2), 475–498.

- Bjorklund, T., Bhatli, D., & Laakso, M. (2013). Understanding idea advancement efforts in innovation through proactive behaviour. Journal of Research in Marketing and Entrepreneurship, 15(2), 124–142.

- Borgogni, L., Petitta, L., & Mastrorilli, A. (2010). Correlates of collective efficacy in the Italian Air Force. Applied Psychology, 59(3), 515–537.

- Carmeli, A., & Paulus, P. B. (2015). CEO ideational facilitation leadership and team creativity: The mediating role of knowledge sharing. Journal of Creative Behaviour, 49(1), 53–75.

- Carmeli, A., & Schaubroeck, J. (2007). The influence of leaders’ and other referents’ normative expectations on individual involvement in creative work. Leadership Quarterly, 18(1), 35–48.

- Carmeli, A., & Spreitzer, G. M. (2009). Trust, connectivity, and thriving: Implications for innovative behaviours at work. Journal of Creative Behaviour, 43(3), 169–191.

- Chen, G., & Bliese, P. (2002). The role of different levels of leadership in predicting self- and collective efficacy: Evidence for discontinuity. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87, 549–556.

- Choi, J. N., & Chang, J. Y. (2009). Innovation implementation in the public sector: An integration of institutional and collective dynamics. Journal of Applied Psychology, 94(1), 245–253.

- Choi, J. N., & Moon, W. J. (2013). Multiple forms of innovation implementation: The role of innovation, individuals, and the implementation context. Organizational Dynamics, 42(4), 290–297.

- Choi, J. N., Price, R. H., & Vinokur, A. D. (2003). Self-efficacy changes in groups: effects of diversity, leadership, and group climate. Journal of Organizational Behaviour: The International Journal of Industrial, Occupational and Organizational Psychology and Behaviour, 24(4), 357–372.

- Chung, G. H., & Choi, J. N. (2018). Innovation implementation as a dynamic equilibrium: Emergent processes and divergent outcomes. Group and Organization Management, 43(6), 999–1036.

- Cohen, L., Duberley, J., & Mallon, M. (2004). Social constructionism in the study of career: Accessing the parts that other approaches cannot reach. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 64(3), 407–422.

- Crant, J. M. (2000). Proactive behaviour in organizations. Journal of Management, 26(3), 435–462.

- Dampérat, M., Jeannot, F., Jongmans, E., & Jolibert, A. (2016). Team creativity: Creative self-efficacy, creative collective efficacy and their determinants. Recherche et Applications en Marketing (English edn, 31(3), 6–25.

- De Jong, J. (2006). Individual innovation: the connection between leadership and employees’ innovative work behaviour (No. R200604). EIM Business and Policy Research.

- De Jong, J. P., & Den Hartog, D. N. (2008). Innovative work behaviour: Measurement and validation. EIM Business and Policy Research, 8(1), 1–27.

- Demircioglu, M. A. (2020). The effects of organizational and demographic context for innovation implementation in public organizations. Public Management Review, 22(12), 1852–1875.

- Demircioglu, M. A., & Audretsch, D. B. (2017). Conditions for innovation in public sector organizations. Research Policy, 46(9), 1681–1691.

- Den Hartog, D. N., & Belschak, F. D. (2012). When does transformational leadership enhance employee proactive behaviour? The role of autonomy and role breadth self-efficacy. Journal of Applied Psychology, 97(1), 194.

- Digital Israel National Initiative. (2017). The national digital program of the government of Israel. https://www.gov.il/BlobFolder/news/digital_israel_national_plan/en/The%20National%20Digital%20Program%20of%20the%20Government%20of%20Israel.pdf.

- Dillman, D. A., Phelps, G., Tortora, R., Swift, K., Kohrell, J., Berck, J., & Messer, B. L. (2009). Response rate and measurement differences in mixed-mode surveys using mail, telephone, interactive voice response (IVR) and the Internet. Social Science Research, 38(1), 1–18.

- Donohoo, J., & Katz, S. (2019). Quality implementation: leveraging collective efficacy to make’ what works’ actually work. Corwin Press.

- Farmer, S. M., Tierney, P., & Kung-Mcintyre, K. (2003). Employee creativity in Taiwan: An application of role identity theory. Academy of Management Journal, 46(5), 618–630.

- Fernández-Ballesteros, R., Díez-Nicolás, J., Caprara, G. V., Barbaranelli, C., & Bandura, A. (2002). Determinants and structural relation of personal efficacy to collective efficacy. Applied Psychology, 51(1), 107–125.

- Fuller Jr J. B., Marler, L. E., & Hester, K. (2012). Bridge building within the province of proactivity. Journal of Organizational Behaviour, 33(8), 1053–1070.

- Gallup Organization. (2011). Innkzobarometer 2010. Analytical report: Innovation in public administration. European Commission.

- Gibson, C. B., & Earley, P. C. (2007). Collective cognition in action: accumulation, interaction, examination, and accommodation in the development and operation of group efficacy beliefs in the workplace. Academy of Management Review, 32(2), 438–458.

- Gong, Y., Huang, J. C., & Farh, J. L. (2009). Employee learning orientation, transformational leadership, and employee creativity: The mediating role of employee creative self-efficacy. Academy of Management Journal, 52(4), 765–778.

- Grant, A. M., & Ashford, S. J. (2008). The dynamics of proactivity at work. Research in Organizational Behaviour, 28, 3–34.

- Griffin, M. A., Parker, S. K., & Mason, C. M. (2010). Leader vision and the development of adaptive and proactive performance: A longitudinal study. Journal of Applied Psychology, 95(1), 174.

- Haase, J., Hoff, E. V., Hanel, P. H., & Innes-Ker, Å. (2018). A meta-analysis of the relation between creative self-efficacy and different creativity measurements. Creativity Research Journal, 30(1), 1–16.

- Hair, J. F., Black, B., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2014). Multivariate data analysis (7th edn). Pearson.

- Holahan, P. J., Aronson, Z. H., Jurkat, M. P., & Schoorman, F. D. (2004). Implementing computer technology: a multiorganizational test of Klein and Sorra’s model. Journal of Engineering and Technology Management, 21(1-2), 31–50.

- Huang, J. (2017). The relationship between employee psychological empowerment and proactive behaviour: Self-efficacy as mediator. Social Behaviour and Personality, 45(7), 1157–1166.

- Isaksen, S. G., & Ekvall, G. (2010). Managing for innovation: The two faces of tension in creative climates. Creativity and Innovation Management, 19(2), 73–88.

- Jacobsen, C. B., & Andersen, L. B. (2014). Performance management for academic researchers: How publication command systems affect individual behaviour. Review of Public Personnel Administration, 34, 84–107.

- Jaiswal, N. K., & Dhar, R. L. (2015). Transformational leadership, innovation climate, creative self-efficacy and employee creativity: A multilevel study. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 51, 30–41.

- Janssen, O. (2005). The joint impact of perceived influence and supervisor supportiveness on employee innovative behaviour. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 78, 573–579.

- Jiang, W., & Gu, Q. (2017). Leader creativity expectations motivate employee creativity: a moderated mediation examination. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 28(5), 724–749.

- Kang, J. H., Matusik, J. G., Kim, T. Y., & Phillips, J. M. (2016). Interactive effects of multiple organizational climates on employee innovative behaviour in entrepreneurial firms: A cross-level investigation. Journal of Business Venturing, 31(6), 628–642.

- Kim, J. S., & Chung, G. H. (2017). Implementing innovations within organizations: A systematic review and research agenda. Innovation, 19(3), 372–399.

- Klein, K. J., & Knight, A. P. (2005). Innovation implementation: Overcoming the challenge. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 14(5), 243–246.

- Lent, R. W., Schmidt, J., & Schmidt, L. (2006). Collective efficacy beliefs in student work teams: Relation to self-efficacy, cohesion, and performance. Journal of Vocational Behaviour, 68(1), 73–84.

- Liu, J., Chen, J., & Tao, Y. (2015). Innovation performance in new product development teams in c hina's technology ventures: the role of behavioural integration dimensions and collective efficacy. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 32(1), 29–44.

- Locke, E. A. (1991). The motivation sequence, the motivation hub, and the motivation core. Organizational Behaviour and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 288–299.

- Madrid, H. P., Patterson, M. G., Birdi, K. S., Leiva, P. I., & Kausel, E. E. (2014). The role of weekly high-activated positive mood, context, and personality in innovative work behaviour: A multilevel and interactional model. Journal of Organizational Behaviour, 35, 234–256.

- Magni, M., Palmi, P., & Salvemini, S. (2018). Under pressure! Team innovative climate and individual attitudes in shaping individual improvisation. European Management Journal, 36(4), 474–484.

- McGorry, S. Y. (2000). Measurement in a cross-cultural environment: survey translation issues. Qualitative Market Research: An International Journal, 3(2), 74–81.

- Moldogaziev, T. T., & Resh, W. G. (2016). A systems theory approach to innovation implementation: Why organizational location matters. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 26(4), 677–692.

- Mumford, M. D. (2003). Where have we been, where are we going? Taking stock in creativity research. Creativity research journal, 15(2-3), 107–120.

- Newman, A., Herman, H. M., Schwarz, G., & Nielsen, I. (2018). The effects of employees’ creative self-efficacy on innovative behaviour: The role of entrepreneurial leadership. Journal of Business Research, 89, 1–9.

- Ng, T. W., & Lucianetti, L. (2016). Within-individual increases in innovative behaviour and creative, persuasion, and change self-efficacy over time: A social–cognitive theory perspective. Journal of Applied Psychology, 101(1), 14.

- OECD (2017). Digital transformation of public service delivery. Government at a glance. https://doi.org/10.1787/gov_glance-2017-72-en

- OECD. (2022). OECD recommendation on digital government strategies. https://www.oecd.org/gov/digital-government/recommendation-on-digital-government-strategies.htm.

- Park, S., & Jo, S. J. (2018). The impact of proactivity, leader-member exchange, and climate for innovation on innovative behaviour in the Korean government sector. Leadership and Organization Development Journal, 39(1), 130–149.

- Parker, S. K., Bindl, U. K., & Strauss, K. (2010). Making things happen: A model of proactive motivation. Journal of management, 36(4), 827–856.

- Piening, E. P. (2011). Insights into the process dynamics of innovation implementation: the case of public hospitals in Germany. Public Management Review, 13(1), 127–157.

- Plimmer, G., Berman, E. M., Malinen, S., Franken, E., Naswall, K., Kuntz, J., & Löfgren, K. (2022). Resilience in public sector managers. Review of Public Personnel Administration, 42(2), 338–367.

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2012). Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annual Review of Psychology, 63, 539–569.

- Puente-Díaz, R. (2016). Creative self-efficacy: An exploration of its antecedents, consequences, and applied implications. Journal of Psychology, 150(2), 175–195.

- Qu, R., Janssen, O., & Shi, K. (2015). Transformational leadership and follower creativity: The mediating role of follower relational identification and the moderating role of leader creativity expectations. Leadership Quarterly, 26(2), 286–299.

- Richter, A. W., Hirst, G., van Knippenberg, D., & Baer, M. (2012). Creative self-efficacy and individual creativity in team contexts: cross-level interactions with team informational resources. Journal of Applied Psychology, 97(6), 1282–1290.

- Rogers, E. M. (2003). Diffusion of innovations. Free Press.

- Scott, S. G., & Bruce, R. A. (1994). Determinants of innovative behaviour: A path model of individual innovation in the workplace. Academy of Management Journal, 37(3), 580–607.

- Shanker, R., Bhanugopan, R., Van der Heijden, B. I., & Farrell, M. (2017). Organizational climate for innovation and organizational performance: The mediating effect of innovative work behaviour. Journal of Vocational Behaviour, 100, 67–77.

- Siddiq, F., Gochyyev, P., & Wilson, M. (2017). Learning in Digital Networks–ICT literacy: A novel assessment of students’ 21st century skills. Computers and Education, 109, 11–37.

- Slavec, A., & Drnovšek, M. (2012). A perspective on scale development in entrepreneurship research. Economic and Business Review, 14, 1.

- Sobel, M. E. (1982). Asymptotic confidence intervals for indirect effects in structural equation models. Sociological Methodology, 13, 290–312.

- Stritch, J. M. (2017). Minding the time: A critical look at longitudinal design and data analysis in quantitative public management research. Review of Public Personnel Administration, 37(2), 219–244.

- Suseno, Y., Standing, C., Gengatharen, D., & Nguyen, D. (2020). Innovative work behaviour in the public sector: The roles of task characteristics, social support, and proactivity. Australian Journal of Public Administration, 79(1), 41–59.

- Tasa, K., Taggar, S., & Seijts, G. H. (2007). The development of collective efficacy in teams: a multilevel and longitudinal perspective. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(1), 17.

- Tierney, P., & Farmer, S. M. (2002). Creative self-efficacy: Its potential antecedents and relationship to creative performance. Academy of Management Journal, 45(6), 1137–1148.

- Tierney, P., & Farmer, S. M. (2004). The Pygmalion process and employee creativity. Journal of Management, 30(3), 413–432.

- Wilson, C., & Mergel, I. (2022). Overcoming barriers to digital government: mapping the strategies of digital champions. Government Information Quarterly, 39(2), 1–13.