IMPACT

How should complex infrastructure projects be managed? A survey of practitioners in public–private partnership (PPP) projects and 35 interviews with these practitioners provided a detailed picture of the management of these projects. The survey research revealed that strict contract management (monitoring performance criteria and sticking to the contract) did not show a significant relationship to either the performance of, or innovation in, these projects. Network management (for example connecting involved parties and exploring new solutions), however, was significant—especially in terms of performance. In the interviews, practitioners highlighted that the complexity of these projects meant that a collaborative relationship between the public and private parties was essential to overcome unforeseen problems. It is therefore advisable to make process agreements at the start of contracts that provide for unexpected issues. The authors conclude that the contract is certainly important but will not generate good performance without active network management and making process rules about how parties can collaborate.

ABSTRACT

Based on economic and governance theories, this article uses survey and interview data to examine the relationship between contract management and network management on the one hand and collaboration, innovation and performance on the other. A positive relationship was found between network management and collaboration and performance. Contract management demonstrated no significant relationship with either collaboration or performance. Additionally, while there was a positive association between network management and innovation, it was not statistically significant. Qualitative data emphasized the complexity of projects and limitations of contracts as a possible explanation.

Introduction

Large public infrastructure projects, like road and railways, have great impact on public space. However, given their complexity, public infrastructure projects are often faced with cost and time overruns (for example Flyvbjerg et al., Citation2003). In an attempt to realize good performance and innovation in these large and complex projects, various management mechanisms have been suggested. These mechanisms have different theoretical underpinnings. On the one hand, economic theories, such as principal–agent theory (De Palma et al., Citation2009) and institutional economics (Williamson, Citation1996), suggest contract-based management styles in which monitoring and performance indicators are key. On the other hand, governance theories, including network and collaborative governance theories (Scharpf, Citation1978; Kickert et al., Citation1997; Ansell & Gash, Citation2008; Torfing, Citation2019), suggest a different type of management that includes a focus on collaboration, joint decision-making and shared interests.

Managerial styles and their theoretical underpinnings

A predominantly economic perspective on managing infrastructure projects would emphasize the risk of opportunistic behaviour. The contract will be presented as a core instrument to manage interactions between partners in large infrastructure projects (for example Jensen & Meckling, Citation1976). Contract management focuses on monitoring the performance based on the agreed performance criteria (De Palma et al., Citation2009). It is designed to keep the project within the agreed timeframe and budget, using the potential for penalties as a sanction mechanism. Strict contract management ensures the collaboration of both partners by punishing opportunistic behaviour but also secures performance and innovation due to the use of clear performance indicators. Against this economic perspective, we might place a more collaboration-oriented perspective on managing infrastructure projects.

In this article, the wide range of literature on network theory and network governance that emphasizes that public policy is formed and implemented in networks (see Rhodes, Citation1997; Kickert et al., Citation1997; Provan & Kenis, Citation2008), and the closely connected literature on collaborative governance (see Ansell & Gash, Citation2008; Emerson & Nabatchi, Citation2015), are presented as the theoretical underpinnings for the network management style. Although there are (conceptual) differences and nuances between network governance and collaborative governance theory, the core assumptions also share significant similarities.

This perspective emphasizes that public infrastructure projects are first and foremost collaborative endeavours and have to be managed as such. It stresses the importance of forms of collaborative or network management, focusing on shared interests and trust building (Agranoff & McGuire, Citation2003; Huxham & Vangen, Citation2005; Steijn et al., Citation2011; Emerson & Nabatchi, Citation2015). It also points out that contracts cannot foresee all unexpected events and developments and consequently co-ordinate the behaviour of partners in these situations. Managing the daily interactions and relationships between partners using collaborative or network management strategies then is essential for achieving good outcomes (Warsen et al., Citation2018).

This article contributes to this ongoing discussion on how to manage large and complex public infrastructure projects. Our research question was:

Which managerial style, contract management or network management, shows the strongest correlation with collaboration, performance and innovation in public infrastructure projects?

The next section of this article elaborates the theoretical framework. An extensive explanation of the research methodology and data collection follows. Next, the empirical findings from the survey are provided; to explore this relationship further and reflect on possible explanations we also use the additional interviews that were done in this research. The article finishes with conclusions and reflections.

Conceptual framework: collaboration, contract- and network management and their influence on performance

As mentioned in the introduction, various management styles have different theoretical underpinnings. Two important different theoretical perspectives on managing infrastructure projects are an economic perspective and a governance perspective. The economic perspective starts from a rational behaviour assumption. Actors act opportunistically. Arrangements, like contracts, performance indicators and penalties are required to avoid opportunistic behaviour and to ensure collaboration between actors. In contrast, the governance perspective focuses much more on the interdependencies between actors and the dynamic and uncertain process of collaboration. This perspective assumes there is a need for continuously fostering collaboration to achieve results. summarizes the main differences between the two perspectives.

Table 1. Two theoretical perspectives on managing public infrastructure projects.

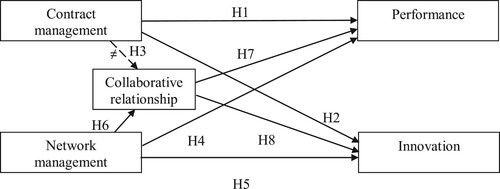

The two theoretical perspectives and their assumptions informed our decision to focus on contract management and network management as the central management styles in this study. The two theoretical perspectives were used to develop a conceptual model on the relationship between managerial style, collaboration, performance and innovation, which could be tested empirically. In the remainder of this section, we first turn to the dependent variables: (performance and innovation) and the intermediate variable (collaboration). Then we further explore the managerial styles and their effect on public infrastructure performance in order to formulate our hypotheses. These hypotheses result in the conceptual model that we test in this study.

Collaboration as key to public service delivery

The need for collaboration and interactions between actors emerges from the dependency of actors on each other’s resources (Rogers & Whetten, Citation1982; Huxham & Vangen, Citation2005). To achieve their goals, actors need each other. Collaboration therefore implies, to some degree, the pooling of resources (Grey, Citation1985; Emerson & Nabatchi, Citation2015). Actors who pool their resources also need to interact and undertake activities regarding the use of these resources. Collaboration can therefore be considered as:

A range of activities—for example information-sharing, coordination interactions and dealing with conflicts (Rogers & Whetten, Citation1982; Huxham & Vangen, Citation2005; Ansell & Gash, Citation2008; Klijn & Koppenjan, Citation2016).

An attitude of considering problems a joint responsibility and acting on that (see also Rogers & Whetten, Citation1982; Agranoff & McGuire, Citation2003).

The importance of collaboration between actors is closely related to the notion of performance and innovation. After all, due to the different interests of actors, for effective performance and innovation there is a need to build interaction structures. Moreover, actors need to engage in the exchange of information (see Ansell & Gash, Citation2008; Emerson & Nabatchi, Citation2015). Sharing information is vital as actors bring in different assets, different knowledge and have different orientations (see Torfing, Citation2019).

Both the collaborative and network governance literature (Warsen et al., Citation2018; Ansell & Gash, Citation2008), as well as the literature on principal–agent and transaction cost theory (Williamson, Citation1996; De Palma et al., Citation2009), acknowledge the need for collaboration and for organizational arrangements in case of (resource) dependency. However, regarding the type of organizational agreement and the way this dependency relationship needs to be managed, the ideas vary widely. The economic perspective emphasizes the use of contracts and contract management as the core organizational arrangement and monitoring and the application of sanctions to ensure that compliance with the selected arrangement (De Palma et al., Citation2009). Collaborative and network governance literature tends to emphasize the interactive character of collaboration and the need for an intensive process and a management style focused on facilitating interaction (see Ansell & Gash, Citation2008; Klijn & Koppenjan, Citation2016; Emerson & Nabatchi, Citation2015).

Performance and innovation in infrastructure projects

The performance of public infrastructure projects is an often-studied topic (for example Khan et al., Citation2021; Locatelli et al., Citation2017). However, evaluating the performance of public infrastructure projects poses a challenge as performance is a multidimensional concept. Hence, various criteria can be used:

Cost performance is one of the most often used criteria to assess the performance of (transport) infrastructure projects, focusing on cost overruns and on budget delivery (see Mantel, Citation2005; Flyvbjerg et al., Citation2003). Various recent studies have shown that such projects often do not manage to stay within their intended budgets (Locatelli et al., Citation2017; Moschouli et al., Citation2018). •After cost performance, schedule or ‘time’ performance is an important evaluation criterion. On time delivery, and meeting the deadlines agreed on in the contract, are important elements of performance (see Mantel, Citation2005; Verweij & Van Meerkerk, Citation2020; Warsen et al., Citation2019). The contract often creates financial incentives for timely delivery and availability. This might not be surprising as infrastructure projects, in particular large projects, are often characterized by a long time span—sometimes taking decades.

The quality of the delivered infrastructure is an important performance indicator (for example Verweij & Van Meerkerk, Citation2020). Recent studies address quality in light of the sustainability of the public infrastructure assessing whether the infrastructure is sustainable over time and how emissions, pollution and material consumption are taken into account in the delivery of the infrastructure (for example Amiril et al., Citation2014).

The satisfaction of the project partners with the project can also be considered an important aspect of performance (Verweij & Van Meerkerk, Citation2020).

Another concept closely related to performance is the notion of ‘innovation’. Innovation, which can be defined as an ‘idea, practice, or object that is perceived as new by an individual or other unit of adoption’ (Rogers, Citation2003, p. 12), is increasingly studied in relation to public infrastructure projects (Callens et al., Citation2022; Carbonara & Pellegrino, Citation2020; Himmel & Siemiatycki, Citation2017). As the definition above shows, innovation is perceived differently by various actors, based on whether or not an actor considers the idea, practice, or object ‘new’ (Callens et al., Citation2022). When it comes to innovation, a distinction is often made between product and process innovations. The first concerns the product that is being made. This might also refer to materials from which the product is made (for example a new type of asphalt). Process innovations deal with the way in which the product is realized and used (De Vries et al., Citation2016; Torfing, Citation2019). For public infrastructure, new ways to organize the construction (for example modular building) and a highway maintenance are clear examples.

To realize innovation in public infrastructure projects, the two central perspectives in this study both suggest different ways to stimulate innovation. The economic perspective focuses mainly on the role of procurement for innovation logics. To stimulate private partners to innovate, this should be part of the public client’s demands. This might be explained using the concept of ‘risk’. Innovation is closely related to risk. Innovation, the adoption of something new, implies uncertainty and, with that, risk (Himmel & Siemiatycki, Citation2017). Partners carrying a great deal of risk in a project might be hesitant to increase their risks. The contract should therefore include requirements that stimulate creative thinking and provide room for exploration (Barlow & Martina, Citation2008; Callens et al., Citation2022). On the other hand, carrying risks might stimulate partners to innovate in order to mitigate risks or save costs. Consequently, risk allocation might affect the realization of innovation. In contrast to traditional contracts, integrated contracts in which private partners are responsible for the Design, Build, Finance & Maintenance (DBFM) of the infrastructure carry the assumption that the long-term and associated risks would stimulate private partners to innovate as they are able to invest more in the quality of the asset and benefit from their innovations in the long run. However, due to the uncertainty of innovations, Roumboutsos and Saussier (Citation2014) suggest that integrated contracts only lead to minor incremental innovations. In their study, Himmel and Siemiatycki (Citation2017) confirmed that innovations in integrated contracted projects mainly focus on lowering the project cost and risk. Instead of revolutionary innovations, innovations ‘are better characterized as ingenuities, defined as clever or inventive ways of doing things’ (Himmel & Siemiatycki, Citation2017, p. 761). More revolutionary innovations are not often achieved. In contrast, the governance perspective ties in with the literature on collaborative innovation logics, in which collaboration is seen as a crucial driver for innovation (Brogaard, Citation2017). As collaboration may lead to close interaction between project partners and information-sharing, this stimulates the realization of innovations. In a recent study, Callens et al. (Citation2022) show that both logics can be mixed and procurement elements, as well as collaborative elements, are found in innovative infrastructure projects.

Strict contract management as a solution: the economic perspective on management

Based on the economic perspective, contract management is considered essential in managing public infrastructure projects. It includes the specifications of the product or service that needs to be delivered, specifies agreements regarding payment, sanctions and monitoring and consequently secures ‘compliance’ of all contract partners. This line of reasoning—based on the principles of (bounded) rationality and opportunistic behaviour—is well known in transaction economics (see Williamson, Citation1996; Jensen & Meckling, Citation1976; Brown et al., Citation2016). Contracts mitigate the risk of opportunistic behaviour because output specifications are laid down in the contract (Brown et al., Citation2016; Mantel, Citation2005). Strict monitoring and—if necessary—the application of sanctions when performance criteria are not met, prevent opportunistic behaviour, keep contract partners in line and stimulate them to achieve the agreements on performance and innovations (Jensen & Meckling, Citation1976; Williamson, Citation1996). Following this line of reasoning, our first two hypotheses regarding the use of strict contract management were:

H1: More strict contract management is positively associated with the performance of public infrastructure projects.

H2: More strict contract management is positively associated with the innovation level of public infrastructure projects.

H3: There is no significant association between (strict) contract management and the collaborative relationship between partners in infrastructure projects.

Network management as a solution: the governance perspective on management

The extensive literature on network and collaborative governance and management takes a rather different approach. It recognizes that, in situations of interdependency, the interactions between actors are moving between co-operation (due to resource dependency) and conflict (due to different interests) (for example Klijn & Koppenjan, Citation2016). The literature stresses that it is highly unlikely that contracts are sufficient to deal with the uncertainty and changing events found in complex situations. Consequently, contracts alone do not lead to high performance or high levels of innovation. Instead, performance and innovations are very unlikely to emerge without collaboration. Intensive managerial efforts are required to realize communication, information-sharing, shared perceptions among partners (Gage & Mandell, Citation1990; Kickert et al., Citation1997; Torfing, Citation2019). Managerial activities include:

Fostering interactions (Scharpf, Citation1978; Klijn & Koppenjan, Citation2016).

Exploring different perceptions of actors (Huxham & Vangen, Citation2005; Ansell & Gash, Citation2008).

Managing conflicts (Ansell & Gash, Citation2008; Emerson & Nabatchi, Citation2015).

Realizing organizational arrangements (Provan & Kenis, Citation2008; Agranoff & McGuire, Citation2003).

Drafting process rules (Klijn & Koppenjan, Citation2016).

H4: More network management activities are positively associated with the performance of public infrastructure projects.

H5: More network management activities are positively associated with the innovation level of public infrastructure projects.

H6: More network management activities are positively associated with a collaborative relationship between partners in public infrastructure projects.

H7: A more collaborative relationship between partners is positively associated with performance.

H8: A more collaborative relationship between partners is positively associated with innovation.

Method

In this section we first address the method used in this study. Next, we turn to the indicators used to measure the core variables in our studies. Finally, we discuss the data analysis and explain our use of structural equation modelling.

A survey among public and private professionals

To test all the hypothesis we conducted a survey among public and private professionals working in either Design & Construct (D&C) or DBFM infrastructure projects commissioned by the Rijkswaterstaat (the Dutch ministry of infrastructure). The survey was part of a systematic evaluation of DBFM projects in The Netherlands (compared to more traditionally procured public infrastructure projects) commissioned by Rijkswaterstaat and the umbrella organization of construction firms (Bouwend Nederland). In total, 396 respondents received an invitation: 160 project and contract managers working for the Rijkswaterstaat and 236 project managers working for private construction companies. This meant that the majority of project managers involved in these types of public infrastructure project were invited to participate in the survey and all possible respondents for the DBFM and D&C projects studied (but we studied all DBFM projects but not all the D&C projects of Rijkswaterstaat).

The data were collected from October 2019 to February 2020. We received 163 completed questionnaires—a response rate of 41%. The response rates for the public and private sector were comparable, although the response rate from Rijkswaterstaat (44%, N = 71) was slightly higher than that from the construction firms (39%, N = 92). Each respondent was asked to complete the survey for a specific project they were involved in. As DBFM projects were compared to more traditionally tendered projects in the evaluation study, both were included in our dataset. DBFM projects (N = 110) were somewhat over represented compared to traditionally procured projects (N = 51); two respondents participated in a project with a different contractual form (Design, Build, Maintenance) and they were excluded. Respondents who did not provide information on all key variables were also removed prior to the analysis, resulting in data from 158 respondents being used for this study.

Finally, the evaluation study also included interviews with 34 public and private professionals working on public infrastructure projects. In the interviews, respondents were asked to share their experiences with DBFM projects and compare the performance of this particular type of contract to more traditionally tendered public infrastructure projects. Although the interviews addressed a broader variety of topics than the variables included in this study, they provided some interesting insights into the mechanisms behind the relationships we were testing in this study. We analysed the interviews, which were transcribed and coded using ATLAS.ti, and used them to illustrate and support the findings of the statistical analysis.

Measuring the items

In line with the theoretical section, performance was measured using indicators regarding goal achievement, cost overrun and the cost–benefit ratio. For innovation, three items from a proven scale were used (see Klijn & Koppenjan, Citation2016). Two items were added to this scale (see I3 and I4 in ), to distinguish between the development of new technologies and their actual use. Network management was measured using five items from a larger scale developed by Klijn et al. (Citation2010). The original scale consisted of 16 items but, due to restrictions in the length of the survey, we selected the items related to exploring and connecting network management strategies, as these strategies had proved to be the most important in the earlier research (see Klijn et al., Citation2010). Contract management was measured using items focused on agreements regarding the budget, deadlines and regarding the monitoring (Mantel, Citation2005). Collaboration was measured using a single item in which respondents were asked to indicate the strength of the collaborative relationship on a scale from 1 to 10. To avoid overlap with the two managerial variables in our study, coordination activities that could also be considered part of collaboration were not included. lists the items for each variable and shows good factor loadings and a good validity.

Table 2. Items and factor loadings for all variables.

Finally, three control variables regarding the characteristics of the project were selected. We included the type of contract (DBFM versus D&C), the complexity of the project and the project size in our model as performance and innovation are more difficult to achieve in complex and large projects. In the process of testing the theoretical model, we also controlled for the background of respondents in terms of whether they were public or private sector respondents. Although we found that public respondents rated the performance of infrastructure projects higher than their private counterparts, this variable did not affect the outcomes of our model regarding the hypotheses. For reasons of clarity, we therefore only present the model in which we controlled for the type of contract (DBFM versus D&C), complexity and project size in this article.

Common source bias

We were interested in experiences related to our key variables from people involved in infrastructure projects and used a cross-sectional survey to gain insight in those experiences. We therefore had to accept a potential common source bias—a frequent criticism of cross-sectional surveys with self-reported data. Following George and Pandey (Citation2017) and Podsakoff et al. (Citation2012), we employed design and statistical remedies to minimize any common source bias. First, respondents were encouraged by their employers (i.e. the Rijkswaterstaat and the building companies involved) to fill out the survey, highlighting the importance of their participation. Second, in the questionnaire, survey questions were clearly separated, by using different shading for multi-item variables and by presenting different variables on separate pages, encouraging respondents to answer the questions independently. In addition, post hoc statistical remedies did not show any common source bias. Following Podsakoff et al. (Citation2012), a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted and a common factor model was estimated. The confirmatory factor analysis showed a reasonable fit (CMIN/DF = 1.64, TLI = 0.91, CFI = 0.93, RMSEA = 0.064 and PCLOSE = 0.052). Subsequently, the results indicated that the difference between the CFA model and a common latent factor model was not significant (χ2 difference = 1.5, df = 1 and p = 0.221). Thus, adding a common latent factor did not improve the model. All in all, while acknowledging the potential of common source bias, there were no indications of any inflated relationships in our data.

Structural equation modeling and convergent validity

The hypotheses were tested by conducting structural equation modeling (SEM) in AMOS version 27. There are multiple advantages in using a structural model as opposed to regression analysis (Byrne, Citation2010). First, all variables can be analysed simultaneously, calculating both direct and indirect effects. Second, SEM uses latent variables, meaning that both unobserved and observed variables are included in the model. Third, the analysis is more accurate, as SEM provides estimates for error variance parameters (Byrne, Citation2010). When conducting structural equation modeling, the first step is to perform a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to assess measurement reliability and validity. This is referred to as the measurement model. In the second step, we tested the structural model with latent variables (see Anderson & Gerbing, Citation1988).

To assess the validity of the model, a CFA was conducted to examine factor loadings of the items used in this study (factor loadings are depicted in ). The fit indices of the measurement model showed a reasonable fit: CMIN/DF = 1.64, TLI = 0.91, CFI = 0.93, RMSEA = 0.064 and PCLOSE = 0.052. Moreover, all factor loadings were above 0.4 (ranging from 0.55 to 0.88). These results verify the posited relationships among the indicators and constructs, therefore showing evidence for convergent validity. To further assess the convergent validity, the average variance extracted (AVE) was calculated. shows that the AVE for most constructs was well above the 0.5 threshold—demonstrating a satisfactory convergent validity (Fornell & Larcker, Citation1981). The AVE for contract management, however, was lower than 0.5. Nonetheless, we can accept an AVE of 0.4 if the composite reliability (CR) is above 0.7. shows that the CR of all constructs, including contract management, was higher than this threshold, so we can conclude that the convergent validity is adequate.

Results

This section presents single correlations between the variables (see ). Among various significant relations, the relationship between network management and collaboration was strongest.

Table 3. Means, standard deviations and correlations among variables.

The structural model

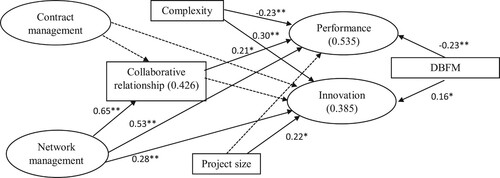

In the second step of structural equational modeling, we modified the structural model when necessary. One of the procedures used to enhance the model was to correlate factor errors of questionnaire items that were similarly worded (Brown, Citation2015). Following this procedure, we correlated the factor errors of contract management (item 1 and 2). Relationships with the lowest significance (i.e. significance levels exceeding 0.05) were deleted, to obtain the most parsimonious model. The structural model that resulted from this yielded a reasonable overall fit: CMIN/DF = 1.63, TLI = 0.91, CFI = 0.93, RMSEA = 0.063 and PCLOSE = 0.060. Therefore we could interpret the results regarding our hypotheses (see also ). The first two hypotheses stated that there is a positive association between stricter contract management and performance (H1) on the one hand and innovation (H2) on the other hand. Both hypotheses are rejected since the association between contract management and both outcome variables were found to be not significant (p > 0.05).

Figure 2. Empirical model.

Notes: The squared multiple correlations are between brackets. Standardized regression coefficients are reported, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01. Latent variables are modelled but not depicted because of visual ease. Non-significant results are visualized by non-continuous arrows.

H3 stated that there is no significant association between strict contract management and a collaborative relationship between partners in infrastructure projects. H3 is confirmed as no significant association was found between contract management and a collaborative relationship (p > 0.05).

H4 and H5 stated that network management is positively associated with performance and innovation of infrastructure projects respectively. We can confirm H4 as the model revealed a significant and strong positive association between network management and performance (β = 0.53, p < 0.001). Related to H5, we did see a positive and significant association between network management and innovation. (β = 0.28, p < 0.001), meaning that H5 is also confirmed.

H6 stated that network management is positively associated with a collaborative relationship between partners in infrastructure projects and was confirmed by the model (β = 0.65, p < 0.001).

The last two hypotheses stated that a collaborative relationship is positively associated with performance of infrastructure projects on the one hand and innovation on the other hand. H7 was confirmed since there was a significant association between a collaborative relationship and performance (β = 0.21, p < 0.05). H8, however, is rejected as a collaborative relationship has a positive but not significant association with the innovation of infrastructure projects (p > 0.05).

With respect to control variables, we found that there is a positive and significant association between both complexity of the project and the size of the project and innovation (β = 0.30, p < 0.001 for complexity and β = 0.22, p < 0.05 for project size). Interestingly, there is a negative and significant association between complexity and performance (β = -0.23, p < 0.01). Related to the type of contract, we found that DBFM contracts seem to result in lower performance (β = -0.23, p < 0.01) but they are more innovative (β = 0.16, p < 0.05). So, the conclusion here might be that larger and more complex projects provide more possibilities for innovations but are more difficult to keep on track in terms of time and budget. The latter has, of course, been mentioned more than once (see Flyvbjerg et al., Citation2003)

What did our qualitative data tell us?

The analysis shows a strong relationship between network management and performance. The effects of collaboration were limited. There was a small, yet significant, relationship with performance but no significant relationship with innovation. Interestingly, several respondents emphasized the importance of collaboration, also for the performance of these projects, in the interviews.

The qualitative data shows that respondents emphasize the activity of collaboration more than the orientation (as measured in the survey). Respondents did not make a distinction between collaborative activities and network management strategies, which they perceived as unavoidably linked to each other. Hence, in their answers, we can actually see support for the importance of network management in public infrastructure projects:

The more you invest in the team, the tender and the implementation the better it is … If you reach a solution in an early stage together with the public client, problems are more manageable (Respondent [R]15—private contractor).

Real relationship management, you can achieve so much with that … Don’t focus on the contract right away, but discuss things first in a meeting and then make sure it is formalized according to the contractual guidelines. That helps to gain better insights in each other’s interests. (R20—private contractor).

Overall, respondents were positive about the contribution of collaboration and network management to the performance of their projects. They addressed, for example, the opportunity to share information, joint problem solving and the importance of open communication for gaining insight in each other’s interests:

Because we need to search for solutions. You need to continue with each other and you need each other in the entire process. So, you’ll have to sit down together, especially when you are presented with huge challenges. And these challenges are shared in projects that run smoothly, because it needs to be solved (R12—private contractor).

Knowledge is power. And sharing knowledge is much more powerful. That’s how I feel about it. I believe you need to share knowledge. Because it only makes you stronger (R19—private contractor).

Just the mere fact that we have a conversation about it already implies that you are working on bringing each other’s interests together. Then, it is no longer a conflicting interest, but it becomes a shared interest … If we don’t tell Rijkswaterstaat [public client] that—hypothetically—we budgeted 12 million euros too short, they can’t brainstorm with us. At the moment that they don’t tell us that they have issues with stakeholders in the environment of the project, we can’t think about solutions for it (R23—private contractor).

The public client used to say: ‘I have put a contract in the market, private contractors have signed for the contract’ … and then we came to the conclusion that this is not the way to co-operate … The damage is only getting worse if you do not engage in conversation with each other (R34—financier).

People by now have the experience to deal with the contract much more easily. And that does not mean they become lazy, they just deal with it better. So, what we call contract management, now also really is managing the contract. In the past, it used to be enforcing the contract. So: ‘I am going to search which article of the contract addresses this issue and tell you what the contract says’. But I already knew that, right? But, how do we manage the contract in light of the best interest of the project? That has improved greatly in the past years. On both sides (R16—private contractor).

There are only a few projects that fully run according to plan. That is not a problem. It is part of the job we do … But then [when things don’t go according to plan] you really need each other (R5—public client).

I think collaboration might work really well … but that does not mean that it was always smooth sailing or that it never hurt, because these are after all very large, complex projects and it involves a lot of money. It is easier to get over a tear in the relationship involving 100 euros than a tear of 100 million euros. Once the amounts grow and the interests grow, then it just becomes, than the relationship comes under pressure (R4—public client).

With the [first] co-operative sessions, the first priority was: how are we going to work together? And then create the 10 golden rules and hold each other to those rules (R22—private contractor).

Overall, the qualitative data provided extra depth to our quantitative analysis. It emphasized the importance of network management. Furthermore, it offered additional explanations as to why network management activities are important and how collaboration improves performance. In line with Brown et al. (Citation2016), our respondents pointed out that the complexity of long-term public infrastructure projects simply makes it impossible to govern these projects by contracts only. Less strict contract management, and the use of network management strategies, allow partners to show some degree of flexibility and jointly search for a solution that satisfies all of their interests.

Conclusions and reflections

This study aimed to analyse the role of contract and network management on the performance and innovation of public infrastructure. The quantitative analysis shows no significant association between contract management on the one hand and collaboration, performance and innovation on the other. This is surprising, as based on economic theories on rational and opportunistic behaviour, we expected at least a significant relationship with performance. In contrast, network management is significantly associated with collaboration and both performance and innovation but more strongly to performance than innovation. Thus innovation in public infrastructure seems to build predominantly on collaborative innovation logics (see also Brogaard, Citation2017). All in all, our study aligns more with the assumptions underlying the governance perspective on managing public infrastructure. The qualitative interview data shows that the complexity of infrastructure projects leading to unexpected developments are important in explaining the importance of network management strategies. Complexity limits the effectiveness of contract management, as strict contract management struggles to deal with unexpected developments taking place regularly in complex infrastructure projects. In general, our study confirms the findings of previous studies that show that strict contract management is not crucial but network and collaborative management styles are very significant to the performance of public infrastructure projects (for example Klijn & Koppenjan, Citation2016; Warsen et al., Citation2018; Citation2019). We are not saying that contracts are not important but, rather, that contract management needs to be complemented with other forms of management to be effective (see also the findings of Warsen et al., Citation2019; Callens et al., Citation2022).

Limitations

As with any study, this study has its limitations. First, the fact that our study was conducted in The Netherlands—a country that has a strong network approach—might affect the findings of this study. Consequently, the question might arise if, and to what degree, the relationship between network management, performance and innovation exists in countries with different administrative cultures, making this a topic suited for further research. Second, the interviews used in addition to the qualitative analysis were part of a larger research project. Hence, they provide only a first indication of the findings and its underlying mechanisms. Future research might want to dig deeper into the mechanisms underlying the relationships found in this study.

Lessons

These findings lead to some important insights for practitioners. First and foremost, although elaborate contracts exist in public infrastructure, it is very important to assess how a contract can be managed in a way that does justice to its underlying principles and takes into account any unforeseen events that may arise. This can best be done by the development of network management strategies, including process agreements. It is also clear that it is not easy to manage public infrastructure projects. Complexity presents a challenge for achieving excellent performance. Moreover, respondents acknowledge that the complexity of the project not only leads to incomplete contracts but also presents a challenge to the collaboration between the public sector client and the private contractor. This means that, even when contract and network management strategies are used, managing large infrastructure projects is always going to be a challenging task. So any simple solution for these projects should be judged with suspicion because it almost certainly cannot be true.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Erik Hans Klijn

Erik Hans Klijn is Professor of Public Administration in the Department of Public Administration and Sociology, Erasmus School of Social and Behavioral Sciences, Erasmus University Rotterdam, The Netherlands.

Samantha Metselaar

Samantha Metselaar is a PhD researcher in the Department of Public Administration and Sociology, Erasmus School of Social and Behavioral Sciences, Erasmus University Rotterdam, The Netherlands.

Rianne Warsen

Rianne Warsen is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Public Administration and Sociology, Erasmus School of Social and Behavioral Sciences, Erasmus University Rotterdam, The Netherlands.

References

- Agranoff, R., & McGuire, M. (2003). Collaborative public management: new strategies for local governments. Georgetown University Press.

- Amiril, A., Nawawi, A. H., Takim, R., & Latif, S. N. F. (2014). Transportation infrastructure project sustainability factors and performance. Procedia—Social and Behavioural Sciences, 153, 90–98.

- Anderson, J. C., & Gerbing, D. W. (1988). Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103(3), 411–423.

- Ansell, C., & Gash, A. (2008). Collaborative governance in theory and practice. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 18(4), 543–571.

- Barlow, J., & Martina, K.-G. (2008). Delivering innovation in hospital construction: Contracts and collaboration in the UK’s private finance initiative hospitals program. California Management Review, 51(2), 126–143.

- Brogaard, L. (2017). The impact of innovation training on successful outcomes in public–private partnerships. Public Management Review, 19(8), 1184–1205.

- Brown, T. A. (2015). Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research. Guilford Publications.

- Brown, T. L., Potoski, M., & Van Slyke, D. (2016). Managing complex contracts: A theoretical approach. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 26(2), 294–308.

- Byrne, B. M. (2010). Structural equation modeling with AMOS: Basic concepts, applications and programming (2nd edn). Routledge/Taylor & Francis.

- Callens, C., Verhoest, K., & Boon, J. (2022). Combined effects of procurement and collaboration on innovation in public-private-partnerships: A qualitative comparative analysis of 24 infrastructure projects. Public Management Review, 24(6), 860–881.

- Carbonara, N., & Pellegrino, R. (2020). The role of public private partnerships in fostering innovation. Construction Management and Economics, 38(2), 140–156.

- De Palma, A., Leruth, L. E., & Prunier, G. (2009). Towards a principal–agent based typology of risks in public-private partnerships. International Monetary Fund.

- De Vries, H., Bekkers, V., & Tummers, L. (2016). Innovation in the public sector: A systematic review and future research agenda. Public Administration, 94(1), 146–166.

- Emerson, K., & Nabatchi, T. (2015). Collaborative governance regimes. Georgetown University Press.

- Flyvbjerg, B., Holm, M. S., & Buhl, S. (2003). How common and how large are cost overruns in transport infrastructure projects? Transport Reviews, 23(1), 71–88.

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(3), 382–388.

- Gage, R. W., & Mandell, M. P. (eds.). (1990). Strategies for managing intergovernmental policies and networks. Praeger.

- George, B., & Pandey, S. K. (2017). We know the yin—but where is the yang? Toward a balanced approach on common source bias in public administration scholarship. Review of Public Personnel Administration, 37(2), 245–270.

- Grey, B. (1985). Conditions facilitating interorganizational collaboration. Human Relations, 38(1), 911–936.

- Himmel, M., & Siemiatycki, M. (2017). Infrastructure public–private partnerships as drivers of innovation? Lessons from Ontario, Canada. Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space, 35(5), 746–764.

- Huxham, C., & Vangen, S. (2005). Managing to collaborate: The theory and practice of collaborative advantage. Routledge.

- Jensen, M. C., & Meckling, W. H. (1976). Theory of the firm: Managerial behaviur, agency costs and ownership structure. Journal of Financial Economics, 3(4), 305–360.

- Khan, A., Waris, M., Panigrahi, S., Sajid, M. R., & Rana, F. (2021). Improving the performance of public sector infrastructure projects: Role of project governance and stakeholder management. Journal of Management in Engineering, 37(2).

- Kickert, W. J. M., Klijn, E. H., & Koppenjan, J. F. M. (1997). Managing complex networks: strategies for the public sector. Sage.

- Klijn, E. H., & Koppenjan, J. (2016). The impact of contract characteristics on the performance of public–private partnerships (PPPs). Public Money & Management, 36(6), 455–462. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540962.2016.1206756

- Klijn, E. H., Steijn, B., & Edelenbos, J. (2010). The impact of network management strategies on the outcomes in governance networks. Public Administration, 88(4), 1063–1082.

- Locatelli, G., Invernizzi, D. C., & Brookes, N. J. (2017). Project characteristics and performance in Europe: An empirical analysis for large transport infrastructure projects. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 98, 108–122.

- Mantel, S. J. (2005). Core concepts of project management. Wiley.

- Moschouli, E., Soecipto, R. M., Vanelslander, T., & Verhoest, K. (2018). Factors affecting the cost performance of transport infrastructure projects. European Journal of Transport and Infrastructure Research, 18(4).

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2012). Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annual Review of Psychology, 63, 539–569.

- Provan, K. G., & Kenis, P. (2008). Modes of network governance: Structure, management and effectiveness. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 18(2), 229–252.

- Rhodes, R. A. W. (1997). Understanding governance: Policy networks, governance, reflexivity and accountability. Open University Press.

- Rogers, D. L., & Whetten, D. A. (eds.). (1982). Inter-organizational coordination: theory, research and implementation. Iowa State University Press.

- Rogers, E. M. (2003). Diffusion of innovations (5th edn). Free Press.

- Roumboutsos, A., & Saussier, S. (2014). Public-private partnerships and investments in innovation: The influence of the contractual arrangement. Construction Management and Economics, 32(4), 349–361.

- Scharpf, F. W. (1978). Interorganizational policy studies: issues, concepts and perspectives. In K. I. Hanf, & F. W. Scharpf (Eds.), Interorganizational policy making: limits to co-ordination and central control. Sage.

- Steijn, A. J., Klijn, E. H., & Edelenbos, J. (2011). Public private partnerships: Added value by organizational form or management? Public Administration, 89(4), 1235–1252.

- Torfing, J. (2019). Collaborative innovation in the public sector: The argument. Public Management Review, 21(1), 1–11.

- Verweij, S., & Van Meerkerk, I. F. (2020). Do public-private partnerships perform better? A comparative analysis of costs for additional work and reasons for contract changes in Dutch transport infrastructure projects. Transport Policy, 99, 430–438.

- Warsen, R., Klijn, E. H., & Koppenjan, J. F. M. (2019). Mix and match: How contractual and relational conditions are combined in successful public–private partnerships. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 29(3), 375–393.

- Warsen, R., Nederhand, J., Klijn, E. H., Grotenbreg, S., & Koppenjan, J. F. M. (2018). What makes public-private partnerships work? Survey research into the outcomes and the quality of co-operation in PPPs. Public Management Review, 20(8), 1165–1185.

- Williamson, O. E. (1996). The mechanisms of governance. Oxford University Press.