IMPACT

While both the academic literature and practice suggest that the use of accounting information is often not neutral, the factors behind a manipulative use of accounting information are under-researched—especially in the public sector context. This article is intended to stimulate the debate about ethical questions related to accounting information manipulation that are often neglected. The authors aim to increase awareness among politicians and public managers about the disputability, or even inappropriateness, of the accounting information they receive.

ABSTRACT

This article explores ethical issues of accounting information manipulation (AIM) in the political arena. After conceptualizing AIM, including its drivers, techniques, contextualities and impacts, the authors discuss underlying tensions between various types of values that emerge as a trigger for applying AIM. In that respect a distinction is made between values at the societal, organizational and individual level, such as, respectively, sustainability, transparency and honesty, and additionally between private values related to personal gain and public values.

Introduction

The preparation of accounting information and its use for analysis and interpretation of the performance of organizations is often not neutral. ‘Neutrality’ refers to actors using information for underpinning their actions in pursuing organizational goals, without serving their specific personal or partisan interests (see, for instance, Burchell et al., Citation1980). In practice, this assumption can be contested. When actors are strongly committed to these interests, they may produce and use information in a way that serves these interests. This can lead to questionable behaviour, which relates to ethical issues of accounting information manipulation (abbreviated here to AIM). The public sector, and particularly the political arena, is an intriguing context in this respect. This is because politicians, who oversee many responsibilities in policy-making and surveillance of managerial decision-making, often pursue individual interests too, like coming into power or preserving their existing power position (Cohen et al., Citation2019), in addition to administrative interests, such as assuring the realization of certain programmes or projects that are beneficial to their voters/citizens.

Ethical or moral aspects of AIM in the political domain are an under-researched area, i.e. whether these practices are understandable or defensible based on values such as honesty, fairness, transparency and organizational performance. Both a review of creative accounting in the public sector (Cardoso & Fajardo, Citation2014; see also Hodges, Citation2018), and a review of earnings management in the public sector (Bisogno & Donatella, Citation2022), either do not or only marginally discuss moral or ethical aspects of these practices. Although the ethics of AIM in the private sector are a more widely studied phenomenon (Merchant & Rockness, Citation1994; Elias, Citation2002; Gowthorpe & Amat, Citation2005), this does not apply to the public sector in general or the political arena in particular. This article attempts to fill a gap in the existing body of knowledge. Before discussing the ethical aspects of AIM in the political arena, we will first explore what AIM is, and under what circumstances it is likely to occur.

Diverging but overlapping labels

There are different labels that overlap, although they are not completely interchangeable, with AIM, among them: ‘earnings management’ (for example Bisogno & Donatella, Citation2022), ‘creative accounting’ (Cardoso & Fajardo, Citation2014), ‘accounting information distortion’ (Birnberg et al., Citation1983), and ‘impression management through accounting numbers’ (Brennan et al., Citation2009).

Earnings management received much scholarly attention and was conducted mainly in a private sector context (Healy & Whalen, Citation1999), as well as healthcare (Malkogianni & Cohen, Citation2022). Earnings management is a purposeful intervention in the external financial reporting process with the intent of obtaining some private gain (Schipper, Citation1989, p. 92). It occurs when managers of private firms use the discretion allowed by accounting rules to show a better financial performance to achieve targets that depend on reported accounting numbers (for example capital market expectations, bonus plans and debt covenants).

Birnberg et al. (Citation1983) propose a broad spectrum of what they call forms of ‘accounting information distortion’. These range from ‘smoothing’ (i.e. moving expenses or revenues from one year to the other) to emphasize or hide certain information elements in order to make the achievements of the actor more impressive (labelled as ‘biasing’, ‘focusing’ and ‘filtering’), and from ‘gaming’ (i.e. pursuing types of behaviour that are valued in existing performance measurement systems but ignore other important issues), to ‘illegal acts’ (for instance when actors move expenses from one item to the another purely to stay within the budgetary boundaries set for each of these items).

In sum, AIM can be related to operating activities, accounting information provision, and the way information is presented.

Conceptualizing accounting information manipulation

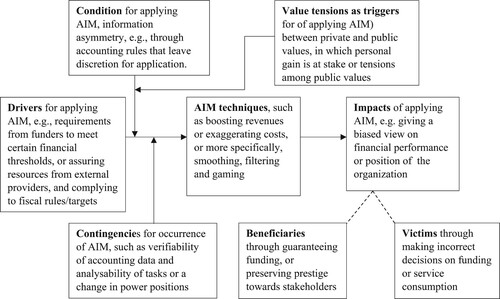

conceptualizes AIM. Drivers for applying AIM may originate from the desire to assure external funding or avoid interventions from outsiders, such as funding or oversight bodies, sometimes also assessing the compliance to fiscal targets/rules (see Hodges, Citation2018). These entities often require that a public sector organization does not show huge surpluses or deficits, so it will sometimes strive to accomplish certain financial thresholds. This impacts the AIM repertoire, as will be justified below.

Figure 1. A conceptual framework for accounting information manipulation (AIM) (source: the authors).

An agency type of relationship in the political arena is seen as condition for applying AIM, and mostly regards the relationship between an executive as agent and the members of the legislative as principal. Such a relationship assumes information asymmetry, i.e. that the manipulating actor (the agent) possesses more or better information than the stakeholder (the principal), and that the actor can benefit from this information advantage (Malkogianni & Cohen, Citation2022). Information asymmetry will be larger if accounting rules leave room for application, or if the auditing function is not well developed. Our claim is that a larger extent of information asymmetry enables a larger degree of AIM which, in turn, is triggered by various types of value tensions. In that respect a distinction can be made between, on the one hand, a tension between private values related to personal gain and public values; and, on the other hand, a tension between different public values. In line with Jones and Euske (Citation1991) and Merchant and Rockness (Citation1994), the first type of value tension is more contested than the latter. To put it simply, striving for personal gain in manipulating accounting data, like strengthening the actor’s power position, is faced with higher moral disapproval than pursuing certain organizational goals, such as assuring sufficient programme funding.

AIM techniques in the public sector can be applied either to the budget or the financial report, and range from rescheduling debt or budget recognition to capitalization of expenses to avoid operational deficits. Operational decisions can also be impacted by AIM, for example when asset sales in privatization are used to increase a surplus instead of decreasing debt (Cardoso & Fajardo, Citation2014; see also Bisogno & Donatella, Citation2022). More specific types of AIM techniques include depreciation that aims to either reduce a surplus (via an additional depreciation), or mitigate a deficit (through a reduced depreciation). This resonates with a so-called ‘around-zero approach’ (see Hodges, Citation2018) when a public sector organization (the actor) does not want to show either huge deficits or huge surpluses—often to avoid interventions by certain stakeholders, such as funding or regulatory institutions.

Manipulation in accounting documents could be distinguished from manipulation through interpretation of published accounting data, which aims to achieve political benefits without necessarily breaking accounting rules. Politicians can frame an interpretation of accounting data and purposefully use it in their public statements (compare Brennan et al., Citation2009 on impression management). This behaviour can then result in not telling the whole truth about the financial performance of the public entity, thus taking advantage from the belief of low verifiability of accounting data.

The ultimate impacts of applying AIM will be a biased presentation of financial information in budgets or reports that may potentially bring beneficiaries for the manipulating actor, but also causes victims, i.e. stakeholders making incorrect decisions because of the distorted information.

Contingencies for accounting information manipulation

Birnberg et al. (Citation1983) highlight contextual circumstances under which accounting information distortion is likely. Their contingency framework is based on two variables, i.e. the belief in measurable and verifiable data, and the belief in the analysability of tasks (see also Hodges, Citation2018). When both variables relate to a high extent of belief, there is very little room for information distortion because tasks are easily analysable and verifiable. Contrasted to this situation, a low belief in these two variables can result in many forms of distortion of data. There are also two in-between situations. On the one hand, a high degree of belief in measurable and verifiable data and a low level belief in analysability of tasks, which makes filtering and focusing acts likely. On the other hand, a minimal belief in measurable and verifiable data and a great belief in analysability of tasks, which makes smoothing, biasing, gaming and illegal acts likely. The two variables of this framework intertwine with information asymmetry: low measurability of data and low analysability of tasks increase information asymmetry.

Also, specific events might give rise to AIM. Guarini (Citation2016), for instance, illustrates that a new politician coming into power, can manipulate accounting data to accuse their predecessor of a heritage of a bad financial performance, which could justify significant austerity measures in the future. In a more general sense, Cohen et al. (Citation2019) found that Greek mayors are more susceptible to AIM when they are re-elected than when they are elected for the first time, because they are more experienced and hence in a better position to manipulate accounting data later in their career.

Tensions between values as triggers of AIM

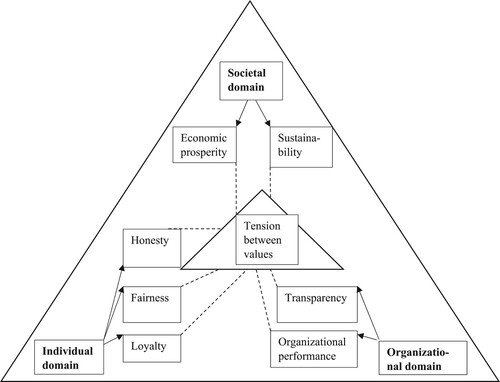

Ethical or moral considerations refer to the values to which actors in the public sector adhere. Values can be seen as the fundamental beliefs of what is good or right, and what is bad or wrong, that guide human attitude and action, including decisions on accounting issues. These values revolve around a ‘moral compass’ for those working in public sector organizations (Gabel-Shemueli & Capel, Citation2013, p. 591; see also Wal et al., Citation2006, pp. 317–318). AIM can be impacted by how people think about these values and, in particular, tensions between different values. A distinction is made between three domains of values, i.e. the societal, the organizational and the individual domain. Tensions can emerge between values within each domain or between these domains (see ). At the individual domain, the following values may exist: honesty (i.e. not withholding relevant information about events or processes), fairness (treating similar cases or persons in an equal way) and loyalty (i.e. a feeling of commitment to a person or a phenomenon). This list of values could, for instance, be expanded with values of integrity, reliability and responsibility (van der Wal et al., Citation2006, p. 332). At the organizational level, transparency/accountability (implying completeness and neutrality of information) is important, but this may conflict with the organizational performance value (which can be defined as showing goal-related results). Finally, the societal domain may include values of economic prosperity and sustainability.

The tale of value tensions

shows that drivers for applying AIM in combination with information asymmetry may be triggered by tensions between various values, and hence to ethical issues. In addition to tensions between values at diverging levels (i.e. the societal, organizational, and individual level), tensions may exist between private and public values, in which a personal gain of the actor is at stake, or among public values. The former will be faced with greater disapproval than the latter. This section presents four examples of these tensions among values, which are not meant to be exhaustive but indicative of our conceptualization in . While the first two examples are indicative of an actor having a personal interest in AIM, the second two examples concern tensions between public values:

First, tensions between values can emerge in the individual and organizational domains. The personal values of the ‘manipulating actor’, such as a member of the executive, often relate to staying in power or achieving a powerful position. This actor could be tempted or encouraged to frame their achievements in a more positive way than is warranted. It is also possible that this actor wishes to hide information about their efforts that would reveal a failure. Then the actor violates the honesty value. This personal value conflicts with the organizational value of transparency.

Second, tensions between diverging personal values, in the individual domain, can lead to AIM. A member of the legislative might, for instance, have feelings of loyalty towards a ‘political friend’, who is part of the executive, but this can conflict with values of honesty. If their political friend displays questionable behaviour, will they then accept that information about this behaviour will be hidden from other stakeholders, or do they prefer transparency about this questionable behaviour and fear the risk of losing a political friend? In these circumstances AIM will be more likely in a context of political rivalry, especially in a coalition–opposition setting.

Third, tensions between different values in the domain of a public sector organization can be a fertile soil for AIM. For instance, an elected politician, especially in an executive position, has an interest in getting things done for their institution—perhaps ensuring sufficient external funding for certain programmes or projects or avoiding interventions from external supervising (or funding) bodies. The latter interests relate to the value of organizational performance. Although holding this value is understandable, it may conflict with values related to accountability based on complete and neutral ways of reporting. Tensions might become problematic when this politician serves the values of getting things done through the manipulation of accounting data, for example by showing a close-to-zero financial result of a programme or project proposal, whereas a neutral budgeting approach would have led to either a substantial deficit or surplus.

Fourth, adherence to the societal value of sustainability might conflict with the organizational performance value in the organizational domain. This could lead to accounting information about sustainability issues, like energy consumption or equal rights for women and men in work relations, without any change in operations and just to impress external stakeholders. Impression management then underlies AIM (compare Brennan et al., Citation2009).

Research approaches

AIM is difficult to assess because it mostly remains fully or partly hidden to outsiders of a public sector organization. Ethical matters are not always (clearly) observable either, especially when they concern forms of unethical behaviour. These circumstances seriously complicate studying the ethics of AIM. Research approaches include theoretical stances and methods, and some brief indications are given in this section (see further indications for future research paths in Bisogno & Donatella, Citation2022, p. 16).

There is a long-standing tradition of investigating earnings management through financial documents (see, for instance, Cohen et al., Citation2019; Bisogno & Donatella, Citation2022). However, the investigation of ethical dimensions of AIM requires other methods, due to the need to disclose underlying reasons for applying AIM. Conducting surveys is, however, questionable, because the delicate nature of ethics is not easily assessable through pre-determined answer categories (see Merchant & Rockness, Citation1994 for a survey study). Observational studies are less suitable because they cannot unravel motives for AIM. We would suggest interview studies using so-called ‘real-life constructs’ (RLCs), which are short cases about certain dilemmas, that enable unfolding both AIM practices and ethical dimensions underlying their application (RLCs in public sector accounting are explained in Argento & van Helden, Citation2022).

Several theoretical stances for studying the ethics of AIM can be considered. This article suggests two theories: agency theory and contingency theory (see ). Contingency theory offers opportunities for studying the contextual circumstances that influence ethical dimensions of AIM (see section on contingencies) and, as such, it has the potential to contribute to literature on earnings management at national and sub-national government level, as well as to the call for more theory-informed approaches to country comparisons (Bisogno & Donatella, Citation2022, pp. 16–17). More specifically regarding AIM in the political arena, it is interesting to study the impact of the political culture of a country on AIM. Italy is, for instance, a more masculine country, while the Netherlands is a more feminine country (Hofstede, Citation2011, pp. 12–13). This can give rise to a more competitive political arena in Italy and a more caring one in the Netherlands. Drivers for AIM could then be stronger in Italy than the Netherlands. Another theoretical option is the application of institutional logics, as the broader cultural beliefs and rules that structure cognition and guide decision-making (Lounsbury, Citation2008).

This article has focused on the agency-relationship in the political arena between a member of the executive as agent, and members of the legislative as principal. However, other agency-relationships in the political arena deserve exploration, for example between members of the executive and managers, in which issues of mutual loyalty can be a fertile soil for AIM. In addition, an agency-relationship between an executive of finance and other executives is possible, in which domain-specific values may collide with transparency values.

Final reflection

To avoid, or at least mitigate, the occurrence of AIM, a better understanding is needed of the drivers that link potential benefits or rewards with intentional AIM in the budgeting and reporting process in the political arena. Our article is meant to provide pointers for this challenging research theme. Manipulating accounting data may seem harmless at first sight but it disadvantages (often innocent) users of accounting information. Manipulators need to live with the idea that they are cheating others.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Jan van Helden

Jan van Helden is Emeritus Professor of Management Accounting at the University of Groningen, The Netherlands. In the 1980s he was member of the executive of the province of Groningen, in charge of Financial and Human Resources affairs. His research is about public sector accounting and management.

Tjerk Budding

Tjerk Budding is a Full Professor in Public Sector Accounting, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, The Netherlands. He has published in leading accounting and public administration journals, including ‘Management Accounting Research’, ‘Financial Accountability & Management’ and ‘International Public Management Journal’.

Enrico Guarini

Enrico Guarini is an Associate Professor of Business Administration and Management, University of Milano-Bicocca, Italy. He does research on public financial management and governance, and he serves as Co-Chair of Local Governance SIG at the International Research Society for Public Management.

Anna Francesca Pattaro

Anna Francesca Pattaro is an Associate Professor of Public Management at the University of Modena and Reggio Emilia, Italy. Her main research interests are public financial management, transparency and accountability, inter-organizational collaborations, governance and sustainability.

References

- Argento, D., & Helden, J. van. (2022). Are public sector accounting researchers going through an identity shift due to the increasing importance of journal rankings? Critical Perspectives on Accounting, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpa.2022.102537

- Birnberg, J. G., Turopolec, L., & Young, S. M. (1983). The organizational context of accounting. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 8(2/3), 111–129.

- Bisogno, M., & Donatella, P. (2022). Earnings management in public-sector organizations: a structured literature review. Journal of Public Budgeting, Accounting & Financial Management, 34(6), 1–25.

- Brennan, N. M., Guillamon-Soarin, E., & Pierce, A. (2009). Impression management; developing and illustrating a scheme of analysis for narrative disclosures—a methodological note. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal, 22(5), 789–832.

- Burchell, S., Clubb, C., Hopwood, A., Hughes, J., & Nahapiet, J. (1980). The roles of accounting in organizations and society. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 5(1), 5–27.

- Cardoso, R. L., & Fajardo, B. G. (2014). Public sector creative accounting: a literature review. https://ssrn.com/abstract=2476593.

- Cohen, S., Bisogno, M., & Malkogianni, I. (2019). Earnings management in local governments: the role of political factors. Journal of Applied Accounting Research, 20(3), 331–348.

- Elias, R. Z. (2002). Determinants of earnings management ethics among accountants. Journal of Business Ethics, 40, 33–45.

- Gabel-Shemueli, R., & Capel, B. (2013). Public sector values; between the real and the ideal. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal, 20(4), 586–606.

- Gowthorpe, C., & Amat, O. (2005). Creative accounting: some ethical issues of macro- and micro-manipulation. Journal of Business Ethics, 57, 55–64.

- Guarini, E. (2016). The day after: newly elected politicians and accounting information use. Public Money & Management, 36(7), 499–506. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540962.2016.1237135

- Healy, P. M., & Whalen, J. M. (1999). A review of the earnings management research and its implications for standard setting. Accounting Horizons, 13(4), 365–383.

- Hodges, R. (2018). How might harmonization influence the future prevalence of public sector creative accounting? Tékhne, 16, 3–14.

- Hofstede, G. (2011). Dimensionalizing cultures: the Hofstede model in context. Online Readings in Psychology and Culture. Article, 8.

- Jones, L., & Euske, K. (1991). Strategic misrepresentation in budgeting. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 1(4), 193–228.

- Lounsbury, M. (2008). Institutional rationality and practice variation: New directions in the institutional analysis of practice. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 33(4-5), 349–361.

- Malkogianni, I., & Cohen, S. (2022). Earnings management in public hospitals: the case of Greek state-owned hospitals. Public Money & Management, 42(7), 491–500. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540962.2022.2071005

- Merchant, K. A., & Rockness, J. (1994). The ethics of managing earnings: An empirical investigation. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 13(1), 79–94.

- Schipper, K. (1989). Commentary on earnings management. Accounting Horizons, 3(4), 102–123.

- Wal, Z. van der, Huberts, L. van den Heuvel, H., & Kolthoff, E. (2006). Central values of government and business: differences, similarities and conflicts. Public Administration Quarterly, 30(3/4), 314-364.