IMPACT

Municipally owned corporations (MOCs) exist across the globe and have become increasingly common. They are motivated by the need for flexibility, a desire to cut costs and to increase efficiency. This article summarizes Swedish experiences with MOCs. It shows that the stated motivations are not necessarily wrong, but that relying heavily on MOCs may have unintended and adverse side-effects. Such side-effects include blurring the role of local politicians, increasing corruption risks and giving rise to complex organizational structures within local governments. Ultimately, transparency and democratic accountability may suffer because of an excessive reliance on MOCs. In particular, councillors, mayors and MOC chief executive officers will benefit from reading these results, and ask themselves what kind of MOCs their municipality should operate, how many MOCs are appropriate to run, and also how members of MOC boards need to be educated.

ABSTRACT

Over the past 30 years, the use of municipally owned corporations (MOCs) has increased rapidly in Sweden. Proponents of MOCs claim that they promote efficiency. However, at the same time, critics stress that MOCs risk blurring accountability, harbour anti-competitive elements and may negatively affect public ethics. The authors review and summarize contemporary research into Swedish MOCs. They highlight that municipalities that create and own relatively more MOCs have higher perceived corruption levels—but not lower taxes, more satisfied citizens or a better business climate. Municipalities with relatively more MOCs display less transparent and more complex organizational structures, where the same politicians hold offices as both principals and agents simultaneously. This runs the risk of short-circuiting accountability chains, thus making it difficult to hold decision-makers accountable. Ultimately, the article contributes to the literature by highlighting the need for taking adverse and unintended side-effects of MOCs into account to better understand their implications for public administration ethics as well as accountability.

Introduction

In Sweden, as well as in several other countries, it has become increasingly common for municipalities to organize their activities in the form of municipally owned corporations (MOCs). However, the hybrid design of MOCs is not uncontroversial. In Sweden, MOCs simultaneously operate under private law (aktiebolagslagen) and public law (kommunallagen). This has led some commentators to conclude that those working within MOCs must navigate in ‘a land of ambiguity’ (Thomasson, Citation2009).

While MOCs, in the broader literature, are often assessed and analysed from a cost-effectiveness perspective, this article sheds light on issues that are often overlooked in the discussion about MOCs—namely issues related to corruption risks and democratic accountability. Both these aspects are unintended and undesirable consequences associated with service delivery by means of MOCs. We ground our arguments by providing empirical illustrations from the Swedish context, where the number of MOCs has been on the rise for at least five decades.

The article is structured as follows. First, we contextualize the issue of MOCs in Sweden by providing some basic numbers and displaying the development over time. Second, we give our perspective on the Swedish development to create better understanding as to why MOCs have become a more common way to operate municipalities’ operations. Third, we discuss MOCs as a particular danger zone for corruption and, fourth, we present dilemmas regarding democratic accountability and whose interests’ politicians—who, in Sweden, almost exclusively are board members of MOCs—should represent. We conclude by summarizing our main findings and highlight the policy implications of them. Although Sweden is our case in focus, we are convinced that some of the Swedish experiences can serve as a cautionary tale as there are some important general lessons to be drawn from the Swedish case and our empirical findings.

The context

Before we delve deeper into the empirical findings from the analyses we have previously conducted, a description of the basic features of Swedish MOCs is warranted. In 2021, corporations with municipalities as majority owners employed approximately 62,000 individuals. This is slightly more than 6.5% of all individuals who are employed by Sweden’s 290 municipalities. The total turnover of MOCs is around SEK 240 billion, which is close to 4.5% of the Sweden’s GDP.

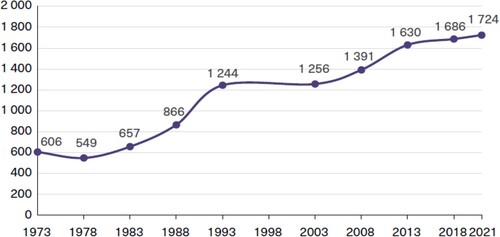

As the pattern in reveals, the MOC trend has been steadily increasing since at least the beginning of the 1970s. Although the number of municipalities has increased (from 278 to 290), the number of corporations per municipality has risen from two to almost six. In per capita terms, the number of MOCs has more than doubled, from one corporation per 13,000 inhabitants in 1973 to one per 6,000 inhabitants in 2021. In reality, the figure is even higher because MOCs that are owned jointly by two or more municipalities are not included in these statistics.

As a result of this substantial increase, MOCs have become important agents in the Swedish economy. They are an important source of revenue for municipalities, particularly in larger cities where positive revenues often come from MOCs operating in housing and real estate (SOU, Citation2015, p. 330).

The most common policy area in which Swedish MOCs operate is public housing and real estate (43% of all MOCs), followed by various technical or ‘hard’ activities such as electricity, gas, heating, cooling, water and sewage (25% of all MOCs). However, as the number of MOCs has increased, their character has become more differentiated and varied. Nowadays, they include activities that for all intents and purposes deviate from what is typically viewed as ‘core’ municipal activities. For instance, there are now MOCs in the fields of culture, entertainment and leisure, as well in the operation of hotels and restaurants. In addition, a handful of MOCs are involved in the repair of cars and motorcycles.

The average number of MOCs for Swedish municipalities is six. However, the variation between municipalities is large: 15 municipalities have more than 20 corporations. The highest number is for Gothenburg with 71 MOCs (Bergh et al., Citation2022). Interestingly, a few years ago, the Confederation of Swedish Enterprise (Svenskt Näringsliv) counted over 90 internal and external corporations in which the city was a full or partial owner (Ryberg, Citation2017). Moreover, over a decade ago, an investigation into corruption problems in the city of Gothenburg found that Gothenburg had ownership interests in about 130 corporations (Amnå et al., Citation2013). The fact that the exact number of corporations in some municipalities is difficult to determine—due to mergers, reorganizations. and divestments—is a strong indication that MOCs tend to contribute to a complex and opaque organizational structure.

The trend that municipalities are creating more and more corporations has been observed across the globe (for example see Andrews, Ferry, Skelcher, & Wegorowski, 2020; Van Genugten et al., Citation2023). Unfortunately, there are few high-quality comparative statistics on MOCs. That said, at least around the turn of the millennium, Sweden was viewed as one of the countries where municipalities had gone the furthest in creating and operating corporations of their own (Dexia Crediop, Citation2004). Other countries—such as Germany, Italy and the Netherlands—seem recently to have had an even stronger growth in MOCs than Sweden (see Grossi & Reichard, Citation2008; Van Genugten et al., Citation2023), but Swedish municipalities undeniably belong to the group of countries that has gone comparatively far in corporatizing parts of their operations.

It should be noted that reliable data before 1970 is unavailable. However, historical records suggest that, in Sweden, a critical debate about the potential negative side-effects of MOCs dates back at least to the late 1960s. For instance, in the early 1970s, the newspaper Göteborgs Handels- och Sjöfartstidning (14 August 1972) pointed out that what they referred to as a ‘jungle’ of MOCs in Gothenburg had grown rapidly in recent years and, also, an editorial in the newspaper Göteborgstidningen (17 December 1971) criticised the increased use of MOCs. Interestingly, and somewhat strikingly, the sceptical arguments put forward more than 50 years ago—which was a fear of deteriorated conditions for accountability, blurred corporate governance and distorted competition—essentially were the same as those in today’s debates.

In one of the earliest papers that we co-authored on this subject—where some worries about the increased use of MOCs by Swedish municipalities were expressed (Erlingsson et al., Citation2008)—we also reviewed a couple of examples of older criticism vis-á-vis Swedish municipalities’ increased use of MOCs. One criticism was made by Torsten Gavelin (Citation1996), then a member of parliament for the Liberal Party. In an opinion piece, this MP maintained that MOCs tend to short-circuit the democratic process and cause scandals because, as he puts it, politicians ‘want to play business-men’ (our translation) although they lack a fundamental understanding about who the company is ultimately for and whose money is at risk (i.e. the tax-payer’s, the citizen’s). Similar lines of argument have also been made by the then director of the Swedish public prosecution authority, Christer van der Kwast, who argued that the relative lack of public control and the higher speed of decision processes—which is a defining characteristic of MOCs—increases the risk of individual’s abusing their power.

Also, the Professor Hans L. Zetterberg (Citation2000) touched upon a similar theme, although with a slightly different take. He did not focus on the lack of public control, but on the increased incentives for individuals to engage in self-interested and shady behaviours when municipalities transferred their activities to MOCs. His observation was that when a bulk of the conversions to MOCs were made in 1991–1994, they were intended to be initial steps towards a straight out privatization of some of the municipalities’ activities. However, subsequent steps towards this final goal were never taken—the privatization projects were halted midway. Local politicians took over the chairmanship of the boards, and basically all seats on all boards (SOU, Citation2015), and by doing this, acquired strong personal incentives to not privatize the activities because the board members, chairmen and chief executive officers still received the same remuneration and ‘golden parachutes’ as if they were working for private enterprises facing fierce competition. The unbundling of the public sector into MOCs in Sweden became, according to Zetterberg, a breeding ground for corruption.

Over the past two decades, criticism of MOCs has intensified and it has been levied from several quarters. For instance, the Swedish Competition Authority, some economists, as well as employers’ organizations, have raised concerns that MOCs carry out activities and provide services that are also provided (or potentially could be provided) by private enterprises on an open market. Therefore. many of the Swedish MOCs may risk distorting fair competition (Konkurrensverket, Citation2014; Lundbäck & Daunfeldt, Citation2013; Indén, Citation2008; Laurent, Citation2007). Entrepreneurs do, in fact, frequently complain that competing with MOCs is unfair, in part due to under-pricing and in part due to municipalities providing financial guarantees and subsidies to their MOCs. The café and restaurant business is a common example of this alleged ‘unfair’ competition. Note that the problem is that the municipality is engaged in activities that compete with private firms, and not necessarily the corporate form as such.

In addition, political scientists and public administration scholars have pointed out that corporate management practices in MOCs are typically weak, unclear—even outright contradictory—and that the corporate form itself tends to worsen transparency and makes auditing and investigative journalism tougher than it ought to be for public organizations (for example SKR, Citation2021; Bergh et al., Citation2019; Thomasson, Citation2009). As a result, MOCs are thought to contribute to a weakening of accountability in local government.

Intimately related to issues concerning accountability, the Swedish National Council for Crime Prevention has noted that corruption cases involving MOCs have tended to increase (Brå, Citation2012). In addition, the Swedish Agency for Public Management found that the awareness of corruption risks within MOCs is low. This, the authors maintain, was particularly disconcerting because the corruption risks associated with organizing one’s operations in the form of MOCs is viewed to be higher compared with public administration proper (Statskontoret, Citation2012).

How can the increase be understood?

The increase depicted in has thus taken place despite harsh and recurrent criticism from a variety of stakeholders. The development makes it essential to understand why the growth in MOCs has taken place. For Italy, Bognetti and Robotti (Citation2007) describe the use of MOCs as a middle-of-the-road strategy to capture economies of scale while simultaneously avoiding loss of political control. For Portugal, Tavares and Camões (Citation2010) note that left-leaning local governments are more likely to use MOCs.

In Bergh et al. (Citation2022) we did not explicitly study the relationship between local government ideology and MOCs. However, re-examining the same dataset reveals a pattern similar to that found in Portugal: municipalities with left-wing local governments had more MOCs in 2013. The tendency for left-wing municipalities to have MOCs, however, does not explain the strong trend in .

In our view there is thus no single, overarching explanation that accounts for the increase. Nevertheless, three plausible circumstances are likely to have been key contributing factors:

First, in the 1980s, Swedish public sector faced criticism for being rigid, overregulated and over-bureaucratized. Back then, corporatizing parts of the municipalities’ operations was seen as a way of enhancing public sector’s flexibility and efficiency by mimicking market mechanisms—not least as a response to efficiency problems in the public sector. Indeed, MOCs were perceived to provide clearer accountability for results, greater financial freedom of action, faster decision-making processes more flexible staffing policies.

Second, after the centre-right victory in the 1991 national election, corporatization of local government operations was intended to be used as a first step in a planned complete privatization of some public sector activities. Here, privatization was politically motivated as many municipalities became governed by centre-right parties after a prolonged period of social democratic rule. However, fully-fledged privatization plans came to a halt after the 1994 elections when many municipalities (re)elected left, centre-left or left-green governments. Thus, without any explicit political force, the lasting effect in many places was that full privatization did not take place, while the corporate form persisted.

Both the points above also suggest that MOCs should be viewed as an integral part of New Public Management (NPM), precisely since they are close to perfect illustrations of the trend towards ‘quasi-privatization’, or ‘middle ground’, in public sector reform (Torsteinsen & Bjørnå, Citation2012; Christensen & Lægreid, Citation2003; see also Thynne, Citation1994). Interestingly, Sweden—and in particular its municipalities—have been argued to have gone comparatively far in implementing NPM reforms by introducing various forms of market mechanisms and the use of performance-based budgeting (see Green-Pedersen, Citation2002). MOCs can be viewed as a part of this trend.

Third, the two explanations above are naturally not exhaustive. The increase in MOCs has continued since 1994 and shows no immediate signs of slowing down. On the contrary. The news outlet Dagens Samhälle (Citation2022) drew attention to an additional explanation for the popularity of MOCs. Several municipalities have recently considered corporatizing their administration of elderly care simply for tax reasons, incidentally an argument that municipalities are frequently blunt about (see Laurent, Citation2007). Tax ‘optimization’ (or ‘avoidance’) is thus an additional explanation for the increased introduction of MOCs. As mentioned, there have been recent reports of municipalities that have already transformed—or are considering transforming—their activities within, for instance, elderly care, with the explicit aim of saving money since MOCs are subject to more generous VAT legislation. This argument for corporatization is not new. According to an estimate made by the Swedish Tax Agency, municipalities withheld at least 600 million SEK annually from the state—but probably far more—through various tax arrangements linked to their MOCs. To the Tax Agency, this was worrying. The agency maintains that since municipalities are tax-funded, non-profit associations—that receive significant contributions from the government—their tax planning can erode trust in the tax system and affect the general willingness to pay taxes (Swedish Tax Agency, Citation2013, p. 21).

MOCs—a danger zone for corruption?

It is difficult to say anything unequivocal about the consequences at the municipal level of having and operating MOCs. It is up to the municipalities themselves to choose whether they want to have them at all, as well as how many corporations they want to own and operate. It is entirely possible that a certain type of municipality is more inclined to organize their activities in the form of corporations.

It is, however, a legitimate endeavour to make systematic comparisons between municipalities to describe what distinguishes municipalities with many corporations from those that own and operate few. Theoretically, there are two ideal-typical and opposing views of MOCs: one rather optimistic and the other slightly more pessimistic.

According to the optimistic view, MOCs contribute to running municipalities’ operations smoothly and more efficiently, thus giving citizens better value for their tax money. The idea is not unreasonable. Compared to public administration proper, MOCs allow more operational flexibility. Indeed, a review article by Voorn et al. (Citation2017) noted that efficiency gains are often realized, particularly for technical operations such as waste collection, water supply, sewage and transportation.

According to the more pessimistic view, corporations run the risk of decreasing transparency, making auditing and accountability more difficult and negatively affecting public ethics, as well as increasing the risk of corruption and distorting free-market competition (see for example Erlingsson et al., Citation2008).

Together with our colleague Emanuel Wittberg, we have empirically contrasted these two opposing approaches (Bergh et al., Citation2022). We examined how the number of corporations varies between Swedish municipalities, how municipalities differ in terms of business climate (as measured by the Confederation of Swedish Enterprise’s annual surveys of local entrepreneurs), how satisfied citizens are with the service provided by their municipality (measured by Statistics Sweden asking citizens about their satisfaction with municipal services), the level of municipal tax rates and an unique, original measure of the perceived level of corruption in the municipality developed by Dahlström and Sundell (Citation2013).

Our results revealed that municipalities with more MOCs have larger perceived corruption problems. Additionally, municipalities who operate many MOCs tend to have slightly higher municipal tax rates while, at the same time, citizens in these municipalities are not more satisfied with municipal services. In addition, municipalities characterized by having many MOCS do not have a better local business climate as measured by the Confederation of Swedish Enterprise (see www.foretagsklimat.se).

All in all, the patterns we observed in Sweden do not support the optimistic view of MOCs. On the contrary, a somewhat more pessimistic view prevails. The relationship between perceived corruption and the number of MOCs was statistically significant at the 1% level (which means that it is very unlikely that the pattern is explained by chance). However, it should be noted that the effect is relatively small. Municipalities with 10 or more corporations have on average 0.12 units higher perceived corruption on a scale from 1 to 7. The effect is not quite as small as this relationship suggests because corruption is rare in most Swedish municipalities (the mean on the 1 to 7 scale is 1.66 and the standard deviation is 0.38).

It is important to note that the correlation between perceived corruption and the number of MOCs in a municipality does not imply that MOCs cause corruption. It is completely plausible that municipalities with higher corruption problems could be more inclined to run their operations through MOCs. A high number of MOCs could thus be seen as a symptom of some underlying problems in the municipality. Theoretically, both mechanisms are reasonable (i.e. that MOCs both cause and are caused by corruption problems). At least to us, this indicates that—in the Swedish setting—there is a risk that MOCs and corruption problems might reinforce each other and spark off vicious circles.

Our study also found the relationship to be weak among municipalities that operated fewer than 10 corporations. It is not at all an implausible interpretation that a smaller number of corporations that operate activities which are well suited to the corporate form is less problematic—or even unproblematic and something to strive for—while municipalities with very many corporations are more prone to problems related to governance and accountability, and thus also constitute corruption risks. Reinforcing this interpretation is the fact that the organizational structure of municipalities quickly becomes more complex and less transparent as the number of MOCs grows and, in complex organizational structures, it is more common for municipal politicians to hold several offices—both as principals and agents—simultaneously (Bergh et al., Citation2019). In the international debate about publicly owned corporations, this has been described as problematic. In situations where individuals that represent the owners (i.e. councillors) regularly are found on the boards of MOCs, in addition to short-circuiting accountability chains, the risk political meddling is always there (for example World Bank, Citation2014; OECD, Citation2018).

An illustration is the City of Gothenburg. When Amnå et al. (Citation2013, p. 181) tried to get to the bottom of why the organizational culture of the City of Gothenburg seemed particularly plagued by corruption problems, they highlighted the far-reaching inclination of Gothenburg’s politicians to create, own and operate MOCs. Amnå and his co-authors found that the municipality had transformed the municipal structures into semi-private corporate structures—without the public sector accountability mechanisms of openness and due process, yet making no effort to ensure that the culture of the MOCs was up to scratch. Amnå’s commission also raised the problem that a municipality with many corporations almost by definition has a precarious problem. Politicians who have seats both on the municipal council and on the boards of MOCs are, on the one hand (as members of the municipal council), responsible for corporate governance and the drafting of ownership directives, while, on the other hand (as members of the boards of MOCs), they are responsible for implementing corporate governance and acting for the good of the company. As highlighted elsewhere in our work (Bergh et al., Citation2019), this way of going about one’s business short-circuits chains of accountability in local government.

What should local politicians do on the boards of MOCs?

Somewhat intriguingly, it turns out to be quite hard to answer the questions that Torsten Gavelin MP raised back in 1996:

Whose interests should the board members of MOC ultimately represent and defend?

On the one hand, Swedish municipalities have a very strong tradition of representative democracy and party loyalty. Politicians on the boards of MOCs come from both the ruling majority and from the opposition and they may or may not also have a seat on the municipal board and the municipal council. In this tradition, it follows that board members who are appointed by political parties also should be loyal to their party (or to their constituents or to their own judgement, depending on how the political mandate is interpreted).

On the other hand, the Swedish Corporation Act is usually interpreted as requiring the board to always look after the best interests of the corporation—not with any other interests. This, in turn, can be interpreted as meaning that party politics should be put aside on the boards of MOCs in favour of constructive and pragmatic work with the best interests of the company in mind. However, the meaning of the term ‘best interests of the corporation’ is ambiguous as far as MOCs are concerned. For privately owned listed corporations, the best interests of the corporation are usually interpreted as the interests of the shareholders as articulated by the shareholders themselves. For a corporation owned by a municipality, it is therefore unclear if board members should give priority to the interests of the municipality or those of the corporation or those of the voters.

What ultimately is in the best interest of the municipality is both difficult to define and the answer is plausibly quite political. Different parties may well have different ideas about what the objectives of MOCs ought to be. It is also worth noting that while private limited companies are often run for profit, under the Municipal Act 2018 (Chapter 3, Section 17), municipalities are—as a rule—not allowed to run their corporations for profit; and all activities carried out by MOCs must have a purpose that is aligned with the interests of the municipality.

We have analysed anonymous responses from 648 local politicians who were asked how they view their mandate (Bergh & Ó Erlingsson, Citation2020). The survey was conducted in spring 2017 in 30 municipalities that were selected both strategically (to include municipalities with different types of corporate structures) and randomly (to increase the possibility of capturing general patterns across Swedish municipalities).

As it turned out, and confirming expectations about ambiguity, politicians are divided on which interests they view as most important—i.e. the municipality’s or the company’s. There are also marked differences of opinion about the role of party politics. Our results can be summarised in three main points:

The view that the interests of the company are more important than those of the municipality was significantly more common among respondents who were themselves represented only on an MOC board compared with politicians who were only represented in the council.

Respondents who were only represented on a company board or only on the council were sceptical about the idea that company board members should represent their own party’s interests. In contrast, respondents were on both a company board and the municipal council (12% of all respondents) tended to be positive about the idea that company board members should represent their party's interests.

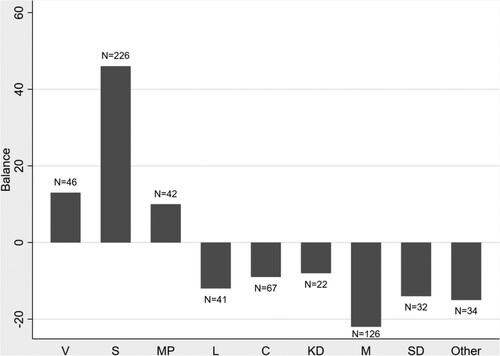

Politicians from social democratic party, the green party and the left party were more likely than others to think that board members should represent their party's interests (see ).

Figure 2. Should MOC board members represent the interests of their political party?

Notes: Balance refers to the percentage of respondents who answered ‘to a great extent’/’to some extent’ minus the percentage who answered ‘not at all/somewhat’. Parties: V = the left party (Vänsterpartiet), S = the social democrats, MP = the green party (Miljöpartiet), L = the liberal party, C = the centre party, KD = the Christian democrats, M = the conservative party (Moderaterna), SD = the Sweden democrats (Sverigedemokraterna). The difference between V, S & MP and the other parties is statistically significant at conventional levels. N is the number of respondents.

Lessons and conclusions

In Sweden, the number of MOCs has grown rapidly in the past three decades. From an NPM perspective, this development could be understood as a rational response to red tape and an inefficient and rigid bureaucracy. And there is no question about it: MOCs have definitely been shown to contribute to strengthening the fiscal performance of the Swedish municipalities (SOU, Citation2015), which is a result fully in line with international experiences (for example Voorn et al., Citation2017). Nonetheless, there seem to be a few drawbacks and unintended side-effects of MOCs that we believe are often overlooked and underestimated both by policy-makers and the broader research community. Below, we briefly list the more prominent controversies that have come to the fore in the past decade’s public debate in Sweden:

The first concerns cases where MOCs display a tendency to distort competition when they enter markets in which private companies are already active (for example Konkurrensverket, Citation2014; Lundbäck & Daunfeldt, Citation2013; Agnorelius & Larsson, Citation2006).

The second concerns problems regarding lack of transparency in the activities of MOCs—not only for citizens and journalists, but also auditors have experienced this (Haglund et al., Citation2021; Haraldsson & Thomasson, Citation2020; Erlingsson & Wittberg, Citation2018; SKR, Citation2021; SKL, Citation2013; SOU, Citation2011; Hyltner & Velasco, Citation2009).

The third is that some municipalities are using their MOCs strategically for (lawful) tax-avoidance schemes (Swedish Tax Agency, Citation2013; Laurent, Citation2007; for example Dagens Samhälle, Citation2022).

The fourth concerns legal ambiguities and ethical concerns when MOCs choose to economically support individuals, events and clubs—particularly élite sports clubs (for example Erlingsson & Hessling, Citation2018).

The fifth concerns a debate about whether Swedish municipalities are competent—or even appropriate—as owners of corporations. For instance, a decade ago, Levander and von Hofsten (Citation2013) complained that only one third of the municipalities regularly evaluated the performance of the boards of their MOCs—and, when they did it, they tended to go about it the wrong way. In a government investigation, SOU (Citation2015, p. 24) devoted an entire chapter to the question about how the boards of MOCs are appointed. The worries expressed here concerned that it almost exclusively was politicians that were appointed to the boards and that female representation on MOC boards was exceptionally poor.

Moreover, our results ought to alert practitioners to the following fact:

Creating, owning and operating MOCs that extend beyond what could pass as basic public good provisions (for example areas such as social housing, technical operations such as electricity, gas, heating, as well as water and sewage) may not only distort private markets but, also, it makes the public sector harder to govern through democratic measures, lowers transparency and blurs accountability.

Given the worrying signals from the public debate, and a few unsettling findings from existing research, it is unfortunate that the critical debates occur in isolation. In view of the growing importance of MOCs in the Swedish municipalities’ economies, we believe that the Swedish government should launch a thorough investigation into the role and importance of MOCs in Sweden. Their numbers have been on the rise over a long period of time (and for a variety of reasons) and there are no signs that the pace is slowing down.

Finally, it bears noting that Swedish research—with the notable exception of Ohlsson’s (Citation2003) now 20-year-old study—has not been particularly interested in empirically studying the cost-efficiency of MOCs. Given the proliferation of MOCs in Swedish local government, this is a surely a research gap that needs to be amended. This is because it is often claimed, but seldom demonstrated, that they are—from a cost-efficiency perspective—a superior way to run the operations of municipalities. That said, the international research literature on MOCs, to us, has something to learn from the Swedish public debate and the research presented in this article. It almost completely lacks the perspective employed here, i.e. that MOCs must be evaluated not only based on their consequences for costs and cost-efficiency, but also from the perspectives of effects on public ethics, transparency, accountability and risks for corruption.

Acknowledgement

This article builds and expands on an essay that has previously been published in Swedish (Bergh & Ó Erlingsson, Citation2022). The authors are grateful to SNS, the Center for Business and Policy Studies, for encouragement to further develop the Swedish version for publication in English.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Andreas Bergh

Andreas Bergh is Associate Professor in Economics at Lund University in Sweden and at the Research Institute of Industrial Economics (IFN) in Stockholm. His research concerns the welfare state, institutions, development, globalization, trust, and populism.

Gissur Ó. Erlingsson

Gissur Ó. Erlingsson is Professor in Political Science at Centre for Local Government Studies, Linköping University, Sweden. His research concerns local democracy, public administration, public corruption, and the values of local self-government.

References

- Agnorelius, J., & Larsson, F. (2006). Osund konkurrens—kommunalt företagande för miljarder. Svenskt näringsliv

- Amnå, E., Czarniawska, B., & Marcusson, L. (2013). Tillitens gränser. City of Gothenburg.

- Andrews, R., Ferry, L., Skelcher, C., & Wegorowski, P. (2020). Corporatization in the public sector: explaining the growth of local government companies. Public Administration Review, 80(3), 482–493. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.13052

- Bergh, A., Ó Erlingsson, G., Gustafsson, A., & Wittberg, E. (2019). Municipally owned enterprises as danger zones for corruption? How politicians having feet in two camps may undermine conditions for accountability. Public Integrity, 21(3), 320–352. https://doi.org/10.1080/10999922.2018.1522182

- Bergh, A., & Ó Erlingsson, G. (2020). Kommunala bolag—i vems intresse? Nordisk Administrativt Tidsskrift, 97(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.7577/nat.4107

- Bergh, A., & Ó Erlingsson, G. (2022). Kommunala bolag—fler nackdelar än fördelar? Studieförbundet Näringsliv och Samhälle.

- Bergh, A., Ó Erlingsson, G., & Wittberg, E. (2022). What happens when municipalities run corporations? Empirical evidence from 290 Swedish municipalities. Local Government Studies, 48(4), 704–727. https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930.2021.1944857

- Bognetti, G., & Robotti, L. (2007). The provision of local public services through mixed enterprises: The Italian case. Annals of Public and Cooperative Economics, 78(3), 415–437. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8292.2007.00340.x

- Brå. (2012). Korruption i kommuner och landsting [Appendix to Statskontoret (2012) Köpta relationer]. Statskontoret.

- Christensen, T., & Lægreid, P. (2003). Coping with complex leadership roles: The problematic redefinition of government-owned enterprises. Public Administration, 81(4), 803–831. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0033-3298.2003.00372.x

- Dagens Samhälle. (2022). Stark kritik mot moms-systemet: ‘I grunden skatteplanering’. www.dagenssamhalle.se/offentlig-ekonomi/kommunal-ekonomi/hard-kritik-mot-momsupplagget-i-grunden-ren-skatteplanering/.

- Dahlström, C., & Sundell, A. (2013). Impartiality and corruption in Sweden. The Quality of Government Institute. https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/43558839.pdf.

- Dexia Crediop. (2004). Local public companies in the 25 countries of the European Union (Dexia and Fédération Des Sem Report No. 2). Dexia. Retrieved from http://www.lesepl.fr/pdf/carte_EPL_anglais.pdf.

- Erlingsson, GÓ, Bergh, A., & Sjölin, M. (2008). Public corruption in Swedish municipalities—trouble looming on the horizon? Local Government Studies, 34(5), 595–608. https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930802413780

- Erlingsson, G. Ó., & Hessling, J. (2018). Hur regleras kommunala bolags möjligheter att sponsra? Centrum för kommunstrategiska studier.

- Erlingsson, GÓ, & Wittberg, E. (2018). They talk the talk—but do they walk the walk? On the implementation of right to information-legislation in Sweden. Scandinavian Journal of Public Administration, 22(4), 3–20.

- Gavelin, T. (1996). Rensa i bolagsdjungeln. Västerbottens-Kuriren (12 September).

- Green-Pedersen, C. (2002). New public management reforms of the Danish and Swedish welfare states. Governance, 15(2), 271–294. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0491.00188

- Grossi, G., & Reichard, C. (2008). Municipal corporatization in Germany and Italy. Public Management Review, 10(5), 597–617. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719030802264275

- Haglund, A., Eklöf, A., & Ricklander, L. (2021). Fem förslag för utveckling av lekmannarevisionen i kommunala aktiebolag. Sveriges Kommuner och Regioner.

- Haraldsson, M., & Thomasson, A. (2020). Lekmannarevisorn—flitig gäst på bolagsstämman? In GÓ Erlingsson, & A. Thomasson (Eds.), Kommunala bolag: styrning, öppenhet och ansvarsutkrävande. Studentlitteratur.

- Hyltner, M., & Velasco, M. (2009). Kommunala bolag—laglöst land. Den Nya Välfärden.

- Indén, T. (2008). Kommunen som konkurrent. Iustus.

- Konkurrensverket. (2014). Kartläggning av kommunala bolags försäljningsverksamhet i konflikt med privata företag.

- Laurent, B. (2007). Varför kommunala bolag? Svenskt Näringsliv.

- Levander, J., & von Hofsten, A. (2013). Våga utvärdera bolagsstyrelserna. Dagens Samhälle (6 November).

- Lundbäck, M., & Daunfeldt, S.-O. (2013). Kommunala bolag som konkurrensbegränsning. Ratio.

- OECD. (2018). State owned enterprises and corruption: What are the risks and what can be done? https://www.oecd.org/corporate/SOEs-and-corruption-what-are-the-risks-and-what-can-be-done-highlights.pdf.

- Ohlsson, H. (2003). Ownership and production costs: Choosing between public production and contracting-out in the case of Swedish refuse collection. Fiscal Studies, 24(4), 451–476. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-5890.2003.tb00091.x

- Ryberg, K. (2017). Göteborg och de kommunala bolagen. https://www.svensktnaringsliv.se/regioner/vastra-gotaland/goteborg-och-de-kommunala-bolagen_1121430.html.

- SKL. (2013). Lekmannarevision i praktiken: Demokratisk granskning av kommunala bolag. Sveriges Kommuner och Landsting.

- SKR. (2021). Fem förslag för utveckling av lekmannarevision i kommunala aktiebolag. Sveriges Kommuner och Regioner.

- SOU. (2011). Offentlig upphandling från eget företag?!—och vissa andra frågor. Fritzes.

- SOU. (2015). En kommunallag för framtiden. Fritzes.

- Statskontoret. (2012). Köpta relationer. Statskontoret.

- Swedish Tax Agency. (2013). Slutrapport: Skatteplanering bland företag som är intressegemenskap med skattebefriade verksamheter [Memo 2013-06-25]. Skatteverket.

- Tavares, A. F., & Camões, P. J. (2010). New forms of local governance: A theoretical and empirical analysis of municipal corporations in Portugal. Public Management Review, 12(5), 587–608. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719031003633193

- Thomasson, A. (2009). Navigating the landscape of ambiguity. Lund University.

- Thynne, I. (1994). The incorporated company as an instrument of government: A quest for comparative understanding. Governance, 7(1), 59–82. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0491.1994.tb00169.x

- Torsteinsen, H., & Bjørnå, H. (2012). Agencies and transparency in Norwegian local government. Scandinavian Journal of Public Administration, 16(1), 5–25. https://doi.org/10.58235/sjpa.v16i1.16201

- Van Genugten, M., Voorn, B., Andrews, R., Papenfuss, U., & Torsteinsen, H. (2023). Corporatisation in local government. Palgrave MacMillan.

- Voorn, B., van Genugten, M. L., & van Thiel, S. (2017). The efficiency and effectiveness of municipally owned corporations: a systematic review. Local Government Studies, 43(5), 820–841. https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930.2017.1319360

- World Bank. (2014). Corporate governance of state-owned enterprises: A toolkit.

- Zetterberg, H. L. (2000). Den kommunala maktbjässens bolag. Dagens Nyheter (1 January).