IMPACT

Universities and public sector organizations need to work together to develop a civil service fit for the future. This article highlights several challenges associated with the development, design, and delivery of public administration (PA) programmes, such as university structures, the elevation of business management programmes, higher education’s focus on international markets and a disconnect between sectoral requirements and PA programme provision. Findings point to a strong demand for specialized public sector education. Yet, they also suggest that public administration academics should do more to promote their programmes and work more closely with professionals, so that a greater understanding of demand and supply can be achieved. To shape the future of the UK civil service, the authors recommend that universities should consider developing more bespoke programmes that better meet the needs of the UK public sector.

ABSTRACT

This research explores the teaching of public administration (PA) in UK universities. Drawing on evidence from three academic and practitioner focus groups, the authors explore debates over PA’s status and identify barriers to PA teaching. Proposed actions to address these barriers include co-design of programmes, greater engagement with accreditation bodies and locally based programmes that support public engagement and impact. The authors demonstrate that a strong demand for PA education still exists, and nuanced forces influence programme location, design, and delivery.

Introduction

Significant moves are being made, particularly in the aftermath of the Covid 19 pandemic, to develop the skills and competence of public servants. For example, the UK government created the Leadership College for Government in April 2022. First announced in the levelling-up white paper (https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/levelling-up-the-united-kingdom), it brought together the Civil Service Leadership Academy and the National Leadership Centre. The OECD has published several reports related to the skills and competencies of civil servants (OECD, Citation2016; Citation2017; Citation2019; Citation2021). The United Nations have developed a curriculum on governance for the Sustainable Development Goals (UNDESA, Citation2021) and a set of standards for public administration (PA) education and training in association with the International Association of Schools and Institutes of Administration (UN IASIA, Citation2008). While several of these initiatives pre-date the Covid 19 pandemic, this public health crisis served to highlight the importance of effective government and, at the same time, raised questions about the role of universities in society. For example, the European University Association has called on universities to be ‘united in their missions of learning and teaching, research, innovation and culture in service to society’ (EUA, Citation2023, p. 5).

Recent research has highlighted a lack of PA teaching in UK universities, and ongoing debates over the status of the subject (Elliott et al., Citation2023). This is in stark contrast to the practice and policy drives for more professional development of public servants seen, for example, in France (École Nationale d'Administration), Canada (the Canada School of Public Service) and Australia and New Zealand (Australia and New Zealand School of Government [ANZSOG]). The lack of UK university involvement (with a small number of exceptions) in supporting the professional development and education of public servants has also been articulated by the Joint University Council (JUC): ‘the State of Minnesota has 8 universities offering MPA programmes, while Scotland (with a similar population size) has only 1 MPA programme’ (JUC, Citation2022, p. 2). Yet the recent development of the UK Association for Public Administration (UKAPA: a new learned society that replaces the JUC’s Public Administration Committee [PAC] that was created in 1918) may offer an opportunity for UK universities to collaborate more closely with each other and with associated international bodies such as the UN Public Administration Network through links with the International Institute of Administrative Sciences (IIAS).

This research explores why there is an apparent lack of teaching PA in the UK and why debates over the status of PA continue. In addressing these questions, we identify barriers to the teaching of PA and propose several actions on how they can be addressed. Our research comprised three focus groups of scholars who taught PA programmes or articulated an interest in PA education in the UK: academics who teach PA; academics who research PA but do not teach the subject; and, finally, practitioners who have an interest in the professional development of public servants. Our conclusions point to important areas that will interest scholars and practitioners who want to see the development of a public service fit for purpose.

The status of public administration education in the UK

PA education continues to innovate and adapt in the UK despite existing in a challenging environment (Bottom et al., Citation2022). The development of the National Leadership Centre, the introduction of degree apprenticeships and a burgeoning postgraduate market, particularly in international students (ibid.; see also Fenwick & Macmillan, Citation2014) have all been highlighted as playing a part in subject’s continued development (Bottom et al., Citation2022). While anecdotal evidence suggests that the apprenticeship levy generated more demand for the teaching of public sector managers, this has largely benefited intakes on generalist as opposed to specialist programmes. Additionally, the levy no longer funds full degrees at Level 7 and this has seen a decline in provision and recruitment.

Specifically, in relation to postgraduate provision, a recent assessment of PA and public management (PM) programmes determined that 30 programmes were taught across 16 higher education institutions (ibid.). These numbers contrast with those seen in the 1980s when taught PA reached its zenith (Jones, Citation2012). This decline, though arguably over exaggerated (Bottom et al., Citation2022), has been attributed to several factors. The rise of business schools and concomitantly MBAs was critical (Liddle, Citation2017), as was the advent of New Public Management (NPM) (Chandler, Citation1991). In turn, New Public Governance (NPG) amplified existing uncertainty regarding the identity of PA (see Rhodes, Citation1995) and facilitated the introduction of new programmes—for example public policy—which further fragmented the market (Jones, Citation2012).

MPAs continue to dominate the UK market and only one undergraduate degree exists, although a wide variety of public sector focused programmes are delivered by further education institutions (ibid.). The majority of university programmes are campus based and commensurate with PA’s vocational nature and over two thirds offer part-time study. A sizable minority are taught via digital or blended platforms, while a handful provide micro credit, capstone, placement or apprenticeship provision (ibid.). It is notable that PA, unlike other social science subjects is taught across several disciplines. Naturally, this influences the epistemology and content of programmes (Elliott et al., Citation2023; see also Liddle, Citation2017)

Programmes remain largely traditional in focus, though the integration of more progressive content is noticeable (Bottom et al., Citation2022; Johnston Miller & McTavish, Citation2011), as are general social science options. Arguably, this eclecticism results in no small part from a lack of guidance on the discipline's parameters. While the majority of UK degrees can be designed and evaluated against subject benchmark statements, this has not been the case for PA. At the time of writing, the Quality Assurance Agency for Higher Education’s (QAA) first subject benchmark statement on public policy and public administration is in development. Its publication has the potential to reinvigorate debate on PA’s identity, programme content and discipline boundaries.

PA has been taught at the higher education level in the UK since the start of the 20th century (Chapman, Citation2007). Unlike in the USA, and several other European countries, it has never attained the standing of other taught subjects in the social sciences. PA has traditionally been considered an unattractive career option (Ritz & Waldner, Citation2011; Shand & Howell, Citation2015) and, perhaps surprisingly, the subject is not part of the secondary level school curricula (Jones, Citation2012). As a result, the potential to attract undergraduates is constrained and the subject is largely confined to postgraduate education, at comparatively few universities. Further, a lack of commitment to education and CPD in public sector practice and government has prevented higher education from establishing strong and durable educational links with the sector.

Despite its apparent resilience and adaptability, it is argued that PA suffers from a combination of disinterest from government and practitioner organizations, disregard from universities and disaffection from many academics (Elliott et al., Citation2023). A reading of the UK PA literature confirms that this status is not new but a long-standing source of frustration for those who believe it warrants greater attention. As discussed above, the internal dynamics of PA education offer some explanation for this situation but the long held ‘uneasy tension’ between universities and the state (Drewry, Citation2024, p. 326) and the legacy of generalism—not specialism—in the UK civil service are particularly instructive (ibid.).

Recently it has been argued that, despite a need for reform and significant change to the environment within which government operates, the development of civil servants has become ‘a forgotten subject’ (Bichard, Citation2020, p. 541). The Covid 19 pandemic, and fears of poly-crises or a perma-crisis, have led many to argue for greater efforts to be made in reconnecting (particularly young) people with public institutions (Eymeri-Douzans, Citation2022). Further, there have been calls for more agile, proactive and resilient policy-making (Bourdin et al., Citation2023). While the Covid 19 pandemic may have accelerated technological innovation across our public services, evidence suggests that, for it to be effective, other aspects of organizational change are necessary (Špaček et al., Citation2023). In addition, it has been suggested that in an increasingly turbulent world characterised by volatility, uncertainty, complexity and ambiguity (VUCA), there is a need for humility and empathy in how we develop a more inclusive PA (O’Flynn, Citation2022).

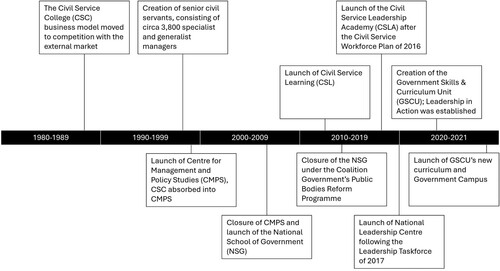

Such calls are by no means new: there is a long track record of institutes and national associations of PA across the world arguing for change. The UK government, UK universities, think tanks and others (particularly from the USA) have been instrumental in the establishment of many of these schools and associations. In the UK, efforts to professionalize the civil service through training, organization and career management have been traced back to the Fulton Report (Walker, Citation2018). It was this report that led to the establishment of the Civil Service College (CSC) in 1970 (Connolly & Pyper, Citation2020). Many of these schools and associations have published academic journals, such as Public Administration first published in 1923 by the Royal Institute of Public Administration (RIPA) (Aoki et al., Citation2022) and the International Review of Administrative Sciences, which was first published in 1928 by the IIAS. While the IIAS continues to operate, RIPA was allowed to dissolve (Chapman, Citation1992). Similarly, the CSC, later rebranded as the National School of Government, was abolished in 2012 (NAO, Citation2022). More recently a Government Skills and Curriculum Unit was established by the UK Cabinet Office to provide training through a new Government Campus (ibid.) (see ). Today it is argued that themes relating to civil service recruitment training and retention have increasingly been neglected in academic research (Bichard, Citation2020), even as the organizational context becomes more complex and fragmented.

Figure 1. Civil service leadership development activities.

Source: NAO (Citation2022), p. 15.

The introduction of the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) highlights the transnational responsibilities that cut across public, private and third sector organizations and the boundary-spanning, network governance and leadership required by the future public service workforce (Buick et al., Citation2019). Internationally, calls for developing the capability and capacity of public services in response to associated poly-crises point to the need for leadership capabilities (Gerson, Citation2020), training and capacity building (European Commission, Citation2023), and the need for practitioners to ‘develop the mindsets, competencies and skills needed to leverage data and tools that can support innovation’ (UN, Citation2023, p. xviii). The UK workforce is fragmented and operates in a decentralized and disaggregated environment (Elliott et al., Citation2022) that has prioritized private sector skills and managerialism (Hood, Citation1991; Chapman, Citation1994; Citation1998) often at the expense of the administrative traditions of probity and equity (Blick & Hennessy, Citation2019; Elcock, Citation2000; Elliott et al., Citation2023; Grimshaw et al., Citation2002; Richards & Smith, Citation2016).

Such an environment limits the ability of the sector to build the capacity and skills necessary to effectively work across public, private and third sector boundaries. Additionally, the public sector workforce has changed. Significant recruitment in recent years has increased its workforce to 5.9 million employees as of September 2023 (ONS, Citation2023a); this comprised 17.8% of the national workforce (ONS, Citation2023b). How do these public servants develop the competence and agility to meet future challenges, particularly in the context of budgetary cuts which have been noted for their deleterious effect on innovation and strategic change (Elliott, Citation2020)? Importantly, the inadequacy of in-house training is well recognized (Needham & Mangan, Citation2016). Recently, the Department for Education drew attention to how recruitment for the newly developed ‘Unit for Future Skills’ was experiencing recruitment challenges due to a shortage of analytical skills in the public sector (Department for Education, Citation2020).

To successfully negotiate, manage and exert effect in public sector environments, officials require higher-level abilities that extend beyond basic role requirements (Adam, Citation2011). Needham and Mangan (Citation2016) refer to the need for relational skills and the ability to negotiate and traverse new dilemmas, while Ongaro emphasises the value of critical thinking (2011; see also Raadschelders, Citation2005). Quinn (Citation2013) draws attention to the importance of reflexive skills and Fuertes highlights the need for expertise and knowledge that ‘could protect against administrative evil and facilitate professionals’ agency against external pressures’ (Citation2021, p. 264). For decades, the UK has steadily reduced the amount of training and development for public service professionals and, where this has taken place, it has increasingly been in professional silos rather than collaborative, generalist subject areas such as PA. While examples of good practice exist, links between the public sector and higher education in the UK are generally precarious and poorly institutionalized.

Three questions remain:

Why do academia–practice links seemingly face such obstacles in the UK?

Despite facing such obstacles, what is it that has enabled PA education to survive?

What else can be done to nurture PA education?

Methodology

The previous section has explained that PA education in the UK operates in a challenging environment. We have also highlighted that this environment appears to be at odds with the position of PA in other countries where its value for supporting a highly functioning public sector is more widely recognized. We now proceed to explore the views and experiences of academics and practitioners around how best to support the professional development of public servants. The study has been approved by university research ethics committees.

Our research has taken a thematic analysis approach. Through its theoretical freedom, thematic analysis provides a flexible and useful research tool, which can potentially provide a rich and detailed, yet complex, account of data (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006, p. 78). Interpretivism is central in this approach to thematic analysis. Braun and Clarke (Citation2006) stress that themes do not simply emerge from the data but from our perceptions of the data. Interpretivism is therefore a key component of our thematic analysis. An interpretivist approach helps make sense of the subjective viewpoints of participants (Bonache & Festing, Citation2020) and brings ‘an appreciation that there are multiple perspectives and voices to be found in relation to a setting’ (Orr & Bennett, Citation2010, p. 200). To recognize human experiences, we must understand the surrounding social milieu (Reissman, Citation1949) and environment within which these experiences take place. For this reason, we employed Braun and Clarke’s six-step approach (Citation2006, p. 87) to explore the perceptions and work–life experiences of PA academics and practitioners engaging with the academic discipline.

Our data is drawn from three separate focus groups: those currently teaching PA; those researching PA, but not teaching it; and practitioners of PA with an interest in education and professional development. In total, we collected 43,433 words of data from 266 minutes of recorded online focus groups with 15 key stakeholders across academia and practice.

Data group one: those teaching PA

Based on recent research (Bottom et al., Citation2022), and knowledge from our professional body (the JUC's PAC—now UKAPA) we identified every university master of public administration/master of public management programme taught throughout the UK. An email was sent to each course director (N = 32) and 28 responded. We asked programme directors to either attend the focus group or nominate an experienced colleague. This was a purposive sample with participants chosen because of their involvement in running and delivering PA courses. The focus group was conducted online via Zoom in June 2023 and comprised six people. The focus group lasted for 99 minutes and participants were from a range of faculties and schools including politics and social science.

Data group two: those researching PA, but not teaching it

We identified, through our professional networks and Google Scholar searches, UK-based academics who were actively engaged in PA scholarship, held journal editorial board positions and published in the top five PA journals (according to the CABS Academic Journal Guide). In total, seven were contacted and four agreed to participate in a focus group. The focus group lasted for 94 minutes, and all participants were from business schools.

Data group three: practitioners of PA with an interest in education and professional development

Our final focus group was derived through snowball sampling. Existing relationships between the PAC (now UKAPA) and practice ensured those responding had an active interest in PA education, as well as practice. This focus group lasted for 73 minutes and involved five participants from local and national government and a major local authority.

We attempted to reach a broad range of participants based on gender, ethnicity, and type of university. However, given the small number of participants, and the relatively small size of the discipline, this information is not provided to maintain anonymity. As is usual, particularly with small target populations, conclusions can only draw upon data from those who chose to participate.

Following Braun and Clarke (Citation2006), themes were identified from the literature and previous research by the authors (Elliott et al., Citation2023): identity issues; the nature of business schools; and perceptions of demand. In addition, emergent themes were identified through the focus group research: the role of equality, diversity and inclusion (EDI) in PA teaching; and the structure and flexibility of formal degree programmes.

It is important to recognize several limitations of this research. It includes findings from only three small focus groups. As such, we do not claim it to be reflective of the experiences of all UK PA academics. Our research was designed in the immediate aftermath of the Covid 19 pandemic. Future research tracking the trajectory of PA education in the UK would be advised to gather data from colleagues at national and international conferences where UK public administration comprise a critical mass (for example PSA, UKAPA and EGPA). It is important that future research examines the perspectives of public sector employers in each devolved region of the UK. These practitioners will often be the funders of such programmes and almost certainly the final beneficiaries. Furthermore, it is essential that the preferences and requirements of past and future students working in practice are ascertained. This research has surfaced the preferences of those commissioning education programmes, not those likely to be studying them.

Findings

Data demonstrated how the three focus groups perceived and discussed the education of pre- and post-experience public servants in the UK. All five themes focused on opportunities and barriers associated with PA education in higher education.

Identity issues

Focus Groups 1 and 2 (FG1 and FG2) recognized a fragmentation of PA and how a lack of understanding of the subject, combined with organizational politics, often pushed PA to the margins:

I am being moved from the politics department, where I've sat for the last 10 years into [a humanities department], which is going to be extremely confusing for my applicants, and will probably put them off in all honesty. And the argument has been that it doesn't matter where this degree sits. Nobody will care. (FG1, P1.)

… they don't really know where to put us. (P5, FG1.)

I think … there are people within politics who look down on it [PA] … that's colleagues who come from the American system … in which public administration is an applied, very separate sort of discipline, they very rarely would share a department. (P4, FG1.)

Wherever I worked, I have felt this … pressure … coming from the rankings of universities … that there are some élite universities trying to shape what the world should look like and I have observed this directly when I was … in [country] when that university decided to strongly internationalise. It became more and more difficult to keep public sector management [subject] whatever teaching there, because they felt that in order to conform with this ideal … . Well, we should do more [private sector focused teaching]. (P10, FG2.)

… what makes me particularly resentful is that … there's also a sort of disdain for the research … it's sort of like ‘I do interesting things with high-powered stats and, or, or very esoteric theory over here, and that's real political science, and you do this really boring mundane thing that no one cares about, but you make some money teaching so that I can have time off to do my important research’ … I'm laying it on thick, but that is the perception that I feel. (P4, FG1.)

So in in my school … it's always like teaching will, will be the priority … we have found it quite difficult to build up a research critical mass because everybody is doing different things because of the teaching requirement. (P5, FG1.)

I've always felt that I've sat at the interface between the more traditional business management studies and then the, the, PAM [public administration and management] fields as well as the third sector … I'll teach a subject like [subject] but will weave in all those sectoral elements across the three sectors. (P8, FG2.)

… with impact case studies, you need to have underpinning research, which means there's quite a lot of academics in business schools, one could argue then doing public management public sector research. (P9, FG2.)

The nature of business schools

All three focus groups recognized the impact of New Public Management and the dominance of the MBA in business schools. Participants in FG2 discussed the traction of MBAs for public sector professionals. One referred to how a large number of public sector professionals often chose to study an MBA but write a public sector focused dissertation:

They study an MBA and they do their research on a public sector issue. (P9, FG2.)

A sense of ‘institutional jealousy’ was recognized in FG2. One participant referred to how endeavours to develop an MPA had been suppressed, seemingly in efforts to protect existing MBAs.

Another academic from the same focus group referred to an MPA programme being withdrawn before it had been allowed to launch:

I mean we even launched it. I think we even got a couple of applications, but then the university decided to pull it out because we weren't really following the trends in the industry. (P7, FG2.)

I'm working on opening an MPA … All the discussion is about how many is it going to be? 100 plus: are you sure about it? I'm sure you will meet the demand and and so on. (P2, FG1.)

Call it part of a larger neoliberal agenda, etcetera, etcetera. But we are all sort of dancing on the same kind of tunes. So if you want to be an élite business school, you will need to have the following programmes and that's, that's it. That pretty much takes all of the resources that business schools have, if they have a bit more and they wish to improvise and experiment with a public sector focus, they, they could. But you know, they don't. (P7, FG2.)

So it's, it's amazing how uniform things are and very disappointing too. But, but yeah, we, we strive towards uniformity rather than actually doing what our consciousness as public sector, public management scholars asked us to do. (P7, FG2.)

I think that one of the difficulties that I've faced over the last eight years is that my students, who are all public sector, have been misdirected towards an MBA … So that's policing and nursing, hospital administration, social services. People have been directed towards an MBA and it's wrong of course. So I'm now seeing those students reapply a year later and coming to me. (P1, FG1.)

The relevance of business programmes integrating relevant public sector content was discussed in FG 2:

… it would be very useful even for people who are working in the private sector to realize that after all [the] private sector, let's say organizations are part of something that is much bigger than this and sometimes we forget about this. (P8, FG2.)

I think it [public sector content] should be more explicit. Absolutely. I think [it] should be more visible. I'm not sure necessarily what form that visibility should take, but certainly it needs to be more visible. (P8, FG2.)

I'm not there to teach [subject] to people just because I want them to focus on increasing profits. I want them to focus on [how] to … so that they can make informed decisions about [a] number of things, for example, decisions which may have an impact … on [a] social kind of variable. (P10, FG2.)

So for me the the question really is if we're having this body of academics … academics doing research in public policy and public management. Does that [research] enter into their teaching? Is there research informed teaching [taking place] or is it people doing public management, public policy research and then their teaching is general management? (P9, FG2.)

Business schools have awoken to the value of public administration and public management … They're different and public management is sort of the compromise they're willing to to take on. And so, I actually see quite a lot of appetite now just this year, a lot of appetite, jobs are coming out again and public management, public administration, public policy, a lot of public policy lingo in those job descriptions. And perhaps this is what the leaders understand to be the value of public sector focus. (P7, FG2.)

Perceptions of demand

Each focus group recognized the need for pre-and post-experience education of public servants. Despite ongoing austerity measures and calls from the government to reduce the size of the workforce, there was a sense amongst academics teaching PA that demand for programmes was growing:

Lots of people were concerned that we will lose our client and our contract will not be renewed because they say, well, government hasn't got money and they don't need to invest in skills … So what, what we actually saw is exactly the opposite of it. (P2, FG1.)

… it is spending to save, isn’t it? (P11, FG3.)

We, we've sort of taken an ethos that local government has a family and … you know if we invest in somebody here and they happen to progress and they go to another organization, well that's still [good]. (P15, FG3.)

I think principally they [university management] don't necessarily connect it [public administration] to student demand, certainly at … undergrad. (P9, FG2.)

… they [university management] do not see the demand for this type of programme and it's up to say an individual academic to push. (P9, FG2.)

… you look at people who entered civil service they had classic degrees, analytical skills and then they would go to Sunningdale, the National School of Government as it was, to kind of get honed in on specific sector specific skills and training. (P9, FG2.)

The … issue I think is that because over the years, new public management has eroded the idea that public administration is a specialist skill. (P9, FG2.)

The best thing about working in local government [in the UK] is like the infinite variety of roles that are available. There are so many different professions … so the role of chief of staff itself is very broad and doesn't have a specific profession attached to it. (P14, FG3.)

And there is an article that appeared in Public Money & Management a few years ago, British students were less likely … to pursue a career in the public sector than Italian students and the authors argued that this had to do with the UK experiencing New Public Management reforms.

P9 (FG2) then drew attention to how millennials tend to exhibit ‘pro-social’ (P9, FG2) behaviours and therefore should be attracted to public sector careers:

And and I think despite what I said, you know that young people may not necessarily be attracted to a career in the public service. They are quite active and vocal. The millennial generation in particular, environmental sustainability, poverty, social issues, all this … But maybe something we need to [do is] tap into [this] and go if you want to make a difference, we can give you the skills to do it … And maybe it's perhaps reaching out to … PAC [now the UKAPA] or the Academy of Social Sciences, it's like this this is something we need to do … The Academy of Social Sciences has what's the campaign for social sciences? … Maybe there should be a campaign for public service.

When you see someone who is heading the government, which is also supposed to be managing and leading on the public sector public services, saying that the private sector is superior and the public sector people should learn from the private sector. That’s it. (P10, FG2.)

The role of equality, diversity and inclusion (EDI) in public administration teaching

Participants from the third focus group stood out by articulating a concern that universities often failed fully meet the sector’s needs. One participant pointed to how the appetite for professional development had become more nuanced:

So I'd say we're [now] being a bit more intelligent and that's part of being part of a … department that that has been created around skills. (P11, FG3.)

So, so for example … we would [be] asking what's your demographic makeup … what are the characteristics of your staff at different levels [they were] not always able to give us that [answer]. (P11, FG3.)

The structure and flexibility of formal degree programmes

A lack of flexibility in higher education seemed to resonate across FG3 and several participants agreed that sustained learning over a period was too great a commitment. As stated by P14 (FG3):

… people just don't have the time to do everything that is needed.

I would probably put the challenge back out … How can we get … universities potentially, to offer accredited programmes that aren't two or three years [long]? (P13, FG3.)

I am not necessarily looking for an individual qualification … it’s about the product more than the placement. (P13, FG3.)

So I think there’s two things in particular we are after … independently derived evidence and [the ability to] respond to that [challenges] and take it a little further to be honest. (P12, FG3.)

[We need the] sort of hard-wired learning like risk management, governance, performance management, budget management, and then there's that softer piece around how do you build resilience? (P15, FG3.)

And I think we need to be thinking creatively around how we partner with the private sector so that people can really understand how, you know, the benefits of … real business understanding.

Discussion and conclusions

Clear need for investment

Without sustained long-term investment in education, training and continuous professional development, there is a risk that government becomes increasingly inefficient, ineffective, and that corruption increases. The CSC, established following publication of the Fulton Report, brought together academics (particularly through the PAC) and civil servants to enhance the teaching of PA and generate research (Chapman and Monroe, Citation1979; Chapman, Citation2007). Its demise, and that of the National School of Government and RIPA in 1992 and 2012 respectively, have been huge losses with significant consequences. Many of these consequences came to light during the Covid 19 pandemic and resultant inquiry and, while moves are being made to address this, there continues to be a lack of understanding and recognition of PA as the key subject area for public servants.

University barriers to engagement

Universities clearly have a role to play here, but our focus groups suggest that often they are either unwilling and/or unable to do so. Business schools seem at times to be actively resistant to the development of public sector relevant education, instead often offering generic business programmes that lack public sector context and basic PA content. The continued pursuit of international students and internationally significant impact feeds into this lack of willingness to invest in supporting the development of public servants at a local or even national level. The failure to recognize EDI and short, flexible course design also makes them unattractive to practitioners. Finally, a failure to recognize both international standards for the education and training of PA, and its professional standards creates further barriers. But, despite these challenges, we also recognize some significant successes that offer important insights on how PA programmes may be developed in future.

The role of learned societies

There are some examples of excellent practice, and many scholars remain committed, often despite institutional challenges, to excellence and impact in PA teaching and research. There is a clear role here for learned societies concerned with PA (such as the International Institute of Administrative Sciences) as well as UKAPA. Such platforms have the capacity to bring together academics and those with an interest in PA to share good practice and develop stronger links with practitioners. Through these networks, academics can work with key stakeholders to ensure that appropriate professional standards are designed into programmes. UKAPA will continue and extend the work of the PAC in helping to restore the voice of PA in the academy and public life, from teaching to government consultations, educational standards and engagement with practice.

Assuring quality of public administration education

Currently only two UK universities (Ulster and Edinburgh) are members of the European Master of Public Administration (EMPA) exchange network and accreditation from professional bodies such as NASPAA (the Network of Schools of Public Policy, Affairs and Administration); the European Association for Public Administration Accreditation (EAPAA); and the International Commission on the Accreditation of Public Administration and Training Programs (ICAPA) remains absent from UK MPA programmes. But the development of a new QAA subject benchmark statement for public policy and public administration offers the potential to start developing PA programmes that are more closely aligned with international standards and the needs of practitioners.

Final thoughts

Overall, this research indicates that current university programmes do not fully align with the needs of practitioners responsible for commissioning professional development in the UK public sector. The evidence presented leads us to conclude that PA scholars and universities would benefit from a greater understanding of what practice requires, while practitioners would benefit from a greater understanding of what MPA programmes can, and should, offer in terms of workforce development. We therefore see significant value in learning and development directorates within national, regional and local government working more closely with PA academics to codesign modules and programmes that maintain academic standards but are practically relevant.

Second, our focus groups revealed that the apparent prestige of MBA programmes (perhaps linked to business school accreditation requirements) comes at the expense of the MPA. In part, this obstacle could be compounded by practitioner indifference to the disciplinary origin of programmes. We assert that the disciplinary home of an MPA programme is a crucial aspect of its focus and content. It is the responsibility of PA academics to do more to convey the merits of the social science origins of their programmes and to emphasise the key public sector relevant skills and concepts conveyed in PA programmes taught by PA scholars. Having more PA programmes that are internationally accredited could be one way to both ensure appropriate content is included and that PA programmes are perceived with the prestige that they deserve. As outlined in the PA literature, and demonstrated in all three focus groups, public sector employees often have different motivation bases, operate in different contexts (with particular political and social challenges), and have different learning needs. This must be taken account of when designing and delivering PA programmes.

Third, MPAs remain attractive in universities that seek to develop in the international market and are designed accordingly. Our research shows that several PA academics perceive universities to be focused on the benefits accrued from international fees, while not recognizing the need for reinvestment from this financial intake. This is resulting in academics’ feelings of isolation and a sense of being misunderstood and undervalued. Correspondingly, very few programmes are designed exclusively with the local/national market in mind. As changes to the REF increase the importance of the research environment, and simultaneously identify engagement as part of the ‘impact’ portfolio, MPA programmes offer a key conjugate for practitioner–academic interaction. The development of such relationships can serve the public sector through providing it with the necessary skills for a modern public sector workforce, but also increase the attractiveness of such organizations as places to work. Public service is an exciting career opportunity; however, the lack of relevant undergraduate and bespoke domestic-market oriented programmes remains a cause for concern and severely limits the opportunity for the academy to influence the skills and behaviours of the civil service over time; given the increasing politicization of the civil service, this may prove to be a significant problem.

To conclude, this initial fieldwork has demonstrated a clear appetite for bespoke public sector education and a willingness of PA researchers and educators to provide this education. Perhaps now is an opportune time for UK practitioners and academics to put into practice the co-design principles they often espouse.

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by a small research grant by the JUC PAC (now UKAPA).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Ian C. Elliott

Ian C. Elliott is a Senior Lecturer in Public Policy and Administration at the University of Glasgow, UK, and co-Editor-in-Chief of ‘Public Administration and Development’. His research interests include the strategic state, organizational change, and teaching public administration. He is co-editor of the ‘Handbook of Teaching Public Administration’ and co-convenor of the EGPA Permanent Study Group IX Teaching Public Administration.

Karin A. Bottom

Karin A. Bottom is an Associate Professor in the Department of Public Administration and Policy and the Institute of Local Government Studies at the University of Birmingham. Karin is co-editor of the ‘Handbook of Teaching Public Administration’ and is currently chairing the advisory group responsible for developing the QAA’s first subject benchmark statement on public policy and public administration. Her research largely focuses on public administration as a taught discipline.

Russ Glennon

Russ Glennon is a Reader in Public Management & Strategy in the Business School’s Department of Strategy, Enterprise and Sustainability at Manchester Metropolitan University, UK. He is the chair of the British Academy of Management’s special interest group in Public Management & Governance and Research. Russ previously held senior positions in local government. His research focuses primarily on performance, accountability, value, and governance in public services.

Karl O’Connor

Karl O’Connor is Professor of Public Administration and Policy within the Centre for Public Administration at Ulster University, UK. He is also the Research Director for Social Work and Social Policy. Karl’s research examines the role of the civil servant in multiethnic societies and in international development.

References

- Adam, G. (2011). The problem of administrative evil in a culture of technical rationality. Public Integrity, 13(3), 275–286. DOI 10.2753/PIN1099-9922130307

- Aoki, N., Elliott, I. C., Simon, J., & Stazyk, E. C. (2022). Putting the international in public administration: An international quarterly. A historical review of 1992–2022. Public Administration, 100(1), 41–58. https://doi.org/10.1111/padm.12822

- Bichard, M. (2020). Editorial: An agenda for civil service change. Public Money & Management, 40(8), 541–545. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540962.2020.1816304

- Blick, A., & Hennessy, P. (2019). Good chaps no more? Safeguarding the constitution in stressful times. The Constitution Society. https://consoc.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/FINAL-Blick-Hennessy-Good-Chaps-No-More.pdf.

- Bonache, J., & Festing, M. (2020). Research paradigms in international human resource management: An epistemological systematisation of the field. German Journal of Human Resource Management, 34(2), 99–123.

- Bottom, K. A., Elliott, I. C., & Moller, F. (2022). Chapter 8: British public administration: the status of the taught discipline. In K. A. Bottom, J. Diamond, P. Dunning, & I. C. Elliott (Eds.), Handbook of teaching public administration (pp. 75–85). Edward Elgar. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781800375697.00020

- Bourdin, S., Moodie, J., Sánchez Gassen, N., Evers, D., Adobati, F., Amdaoud, M., Arcuri, G., Casti, E., Cottereau, V., Eva, M., Lőcsei, H., Iaţu, C., Iba˘nescu, B., Jean-Pierre, P., Hermet, F., Levratto, N., Löfving, L., Coll-Martinez, E., Psycharis, Y., … Remete, Z. (2023). Covid 19 as a systemic shock: curb or catalyst for proactive policies towards territorial cohesion? Regional Studies, https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2023.2242387

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Buick, F., O’Flynn, J., & Malbon, E. (2019). Boundary challenges and the work of boundary spanners. In H. Dickinson, C. Needham, C. Mangan, & H. Sullivan (Eds.), Reimagining the future public service workforce (pp. 81–92). Springer.

- Chandler, J. A. (1991). Public administration: A discipline in decline. Teaching Public Administration, 11(2), 39–45. https://doi.org/10.1177/014473949101100205

- Chapman, R. A. (1992). The demise of the Royal Institute of Public Administration (UK). Australian Journal of Public Administration, 51(4), 519–520.

- Chapman, R. A. (1994). Change in the civil service. Public Administration, 72(4), 599–610. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9299.1994.tb00811.x

- Chapman, R. A. (1998). Problems of ethics in public sector management. Public Money & Management, 18(1), 9–13. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9302.00098

- Chapman, R. A. (2007). The origins of the Joint University Council and the background to Public Policy and Administration. Public Policy and Administration, 22(1), 7. DOI: 10.1177/0952076707071500

- Chapman, R. A., & Munroe, R. (1979). Public administration teaching in the civil service. Teaching Politics, 8, 1–12.

- Connolly, J., & Pyper, R. (2020). Developing capacity within the British civil service: the case of the Stabilisation Unit. Public Money & Management, 40(8), 597–606. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540962.2020.1750797

- Department for Education. (2020). Apprenticeship starts since May 2010 and May 2015 by region, local authority and parliamentary constituency as of Q3 2019/20, Apprenticeships and traineeships data. https://www.gov.uk/government/statistical-data-sets/fe-data-library-apprenticeships.

- Drewry, G. (2024). United Kingdom. In T. Kerkhoff, & D. Moschopoulos (Eds.), The education and training of civil servants (pp. 315–341). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Elcock, H. (2000). Management is not enough: we need leadership!. Public Policy and Administration, 15(1), 15–28. https://doi.org/10.1177/095207670001500103

- Elliott, I. C. (2020). Organizational learning and change in a public sector context. Teaching Public Administration, 38(3), 270–283. https://doi.org/10.1177/0144739420903783

- Elliott, I. C., Bottom, K. A., Carmichael, P., Liddle, J., Martin, S., & Pyper, R. (2022). The fragmentation of public administration: Differentiated and decentered governance in the (dis)United Kingdom. Public Administration, 100(1), 98–115. https://doi.org/10.1111/padm.12803

- Elliott, I. C., Bottom, K. A., & O’Connor, K. (2023). The status of public administration teaching in the UK. Journal of Public Affairs Education, 9(3), 262–274. https://doi.org/10.1080/15236803.2023.2202609

- EUA. (2023). Universities without walls: A vision for 2030. https://eua.eu/downloads/publications/universities%20without%20walls%20%20a%20vision%20for%202030.pdf.

- European Commission. (2023). Enhancing the European administrative space (ComPAct). https://commission.europa.eu/system/files/2023-10/2023.4890%20HT0423966ENN-final.pdf.

- Eymeri-Douzans, J. (2022). Your country needs you! For a new policy of public service attractiveness targeting our next generations. Transylvanian Review of Administrative Sciences, 18(SI), 52–69. http://doi.org/10.24193/tras.SI2022.5

- Fenwick, J., & Macmillan, J. (2014). Public administration, what is it, why teach it and why does it matter? Teaching Public Administration, 32(2), 194–204. doi.org/10.1177/0144739414522479

- Fuertes, V. (2021). The rationale for embedding ethics and public value in public administration programmes. Teaching Public Administration, 39(3), 252–269. https://doi.org/10.1177/01447394211028275

- Gerson, D. (2020). Leadership for a high performing civil service: Towards senior civil service systems in OECD countries. OECD Working Papers on Public Governance, No. 40. OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/ed8235c8-en

- Grimshaw, D., Vincent, S., & Willmott, H. (2002). Going privately: partnership and outsourcing in UK public services. Public Administration, 80(3), 475–502. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9299.00314

- Hood, C. (1991). A public management for all seasons? Public Administration, 69(1), 3–19. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9299.1991.tb00779.x

- Johnston Miller, K., & McTavish, D. (2011). Women in UK public administration scholarship? Public Administration, 89(2), 681–697. doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9299.2010.01895.x

- Jones, A. (2012). Where has all the public administration gone? Teaching Public Administration, 30(2), 124–132. https://doi.org/10.1177/0144739412462169

- JUC. (2022). Designing a public services workforce fit for the future. Response to consultation Written evidence (FFF0023). https://committees.parliament.uk/writtenevidence/106671/pdf.

- Liddle, J. (2017). Is there still a need for teaching and research in public administration and management? A personal view from the UK. International Journal of Public Sector Management, 30(6), 575–583. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPSM-06-2017-0160

- NAO. (2022). Leadership development in the civil service. https://www.nao.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/011074-Leadership-dev-Book.pdf.

- Needham, C., & Mangan, C. (2016). The 21st century public servant: working at three boundaries of public and private. Public Money & Management, 36(4), 265–272. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540962.2016.1162592

- OECD. (2016). Engaging public employees for a high-performing civil service. https://www.oecd.org/gov/pem/engaging-public-employees-for-a-high-performing-civil-service-9789264267190-en.htm.

- OECD. (2017). Skills for a high performing civil service. https://www.oecd.org/gov/skills-for-a-high-performing-civil-service-9789264280724-en.htm.

- OECD. (2019). Recommendation of the council on OECD legal instruments public service leadership and capability. https://www.oecd.org/gov/pem/recommendation-on-public-service-leadership-and-capability.htm.

- OECD. (2021). Public employment and management 2021: the future of work in the public service. https://www.oecd.org/gov/public-employment-and-management-2021-938f0d65-en.htm.

- O’Flynn, J. (2022). A global perspective on public administration? The dynamics shaping the field and what it means for teaching and learning. In K. A. Bottom, J. Diamond, P. Dunning, & I. C. Elliott (Eds.), Handbook of teaching public administration (pp. 75–85). Edward Elgar. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781800375697.00020

- ONS. (2023a). Public sector employment, UK: September 2023, published 12 December 2023, ONS website, statistical bulletin, https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/publicsectorpersonnel/bulletins/publicsectoremployment/september2023.

- ONS. (2023b). Public sector employment as % of total employment; Source dataset: Public sector employment time series (PSE), https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/publicsectorpersonnel/timeseries/db36/pse.

- Orr, K., & Bennett, M. (2010). Editorial. Public Money & Management, 30(4), 199–203. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540962.2010.492171

- Quinn, B. (2013). Reflexivity and education for managers teaching public administration. Teaching Public Administration, 31(1), 6–17. https://doi.org/10.1177/0144739413478961

- Raadschelders, J. C. N. (2005). Government and public administration: The challenge of connecting knowledge. Administrative Theory and Praxis, 27(4), 602–627. https://doi.org/10.1080/10841806.2005.11029515

- Reissman, L. (1949). A study of role conceptions in bureaucracy. Social Forces, 27(3), 305–310. https://doi.org/10.2307/2572184

- Rhodes, R. A. W. (1995). The changing face of British public administration. Politics, 15(2), 117–126. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9256.1995.tb00129.x

- Richards, D., & Smith, M. J. (2016). The Westminster model and the ‘invisibility of the political and administrative élite’: a convenient myth whose time is up? Governance, 29(4), 499–516. https://doi.org/10.1111/gove.12225

- Ritz, A., & Waldner, C. (2011). Competing for future leaders: A study of attractiveness of public sector organizations to potential job applicants. Review of Public Administration, 31(3), 291–316. https://doi.org/10.1177/0734371X11408703

- Shand, R., & Howell, K. E. (2015). From the classics to the cuts: Valuing teaching public administration as a public good. Teaching Public Administration, 33(3), 211–220. https://doi.org/10.1177/0144739415587394

- Špaček, D., Navrátil, M., & Špalková, D. (2023). New development: Covid 19 and changes in public administration—what do we know to date? Public Money & Management, 43(8), 862–866. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540962.2023.219954

- UN. (2023). World public sector report 2023. https://publicadministration.desa.un.org/publications/world-public-sector-report-2023.

- UNDESA. (2021). Developing capacities for effective governance for the Sustainable Development Goals. UN Department for Economic and Social Affairs. https://unpan.un.org/sites/default/files/inline-files/Report%20on%20Piloting%20trainings%20of%20the%20Curriculum-min_0.pdf.

- UN IASIA. (2008). Standards of excellence for public administration education and training. https://iasia.iias-iisa.org/accf/Standards%20of%20Excellence%20English.pdf.

- Walker, D. (2018). Debate: Fulton at 50—Whitehall still doesn't get it. Public Money & Management, 38(6), 461–462. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540962.2018.1471279