IMPACT

The increasing disconnect between academia and central and local government accounting (CLGA) practices have significant implications for the quality of public sector accounting (PSA) especially for preparers as well as users of governmental accounting reports. Particularly transparency and understandability of accounting are at stake. The extinction of CLGA education at higher education institutions (HEIs) will deprive public sector organizations of the opportunity to hire graduates who are knowledgeable about the peculiarities of the public sector. This article shows how the negative self-reinforcing processes that increase the decoupling of academia from accounting practice can be reversed by rethinking the way academia collaborates with practitioners. Policy-makers and public sector managers should encourage HEIs to establish innovative competence improvement courses in PSA and increase the number of public sector PhDs. Specifically, digital micro-courses that can be offered to identify problems and propose solutions related to central and local government accounting can be a tool to reduce the practice–academia disconnect.

The development of the academia–practice disconnect is analysed in the case of Norwegian public sector accounting (PSA) education, which has experienced dramatic drops in the number of courses offered and the number of students enrolled. By mobilizing the theory of path dependency, the authors show how self-reinforcing institutional processes have led to such an extinction. It is suggested that academia can attempt to reverse the process towards extinction by developing courses for practitioners outside formal degree structures.

Introduction

The academia–practice disconnect has been a well-documented concern for decades (Bolton & Stolcis, Citation2003; Tucker & Lowe, Citation2014; Fraser et al., Citation2020; Daugherty et al., Citation2023). This disconnect is harmful because it imposes social and economic costs to our society (Wilkinson & Durden, Citation2015; Ghoshal, Citation2005; Ferraro et al., Citation2005). Academia clearly needs to enhance its societal impact (Parker et al., Citation2011; AACSB, Citation2022; Daugherty et al., Citation2023).

The field of public sector accounting (PSA) is an important example of this disconnect. Successful PSA developments rely on relevant research (Van Helden & Argento, Citation2020) and public servants receiving appropriate education and training (Sciulli & Sims, Citation2007). However, a lack of proper education and training for public servants remains a common issue in PSA (Karatzimas et al., Citation2022, p. 543). Ensuring relevant education at various levels can contribute to more competent and well-prepared public servants (Novin et al., Citation1997; Campbell et al., Citation2000; Grossi et al., Citation2023). Despite the expectation that PSA practice and academia should be closely related (Heiling, Citation2020), an academia–practice disconnect persists in the field of PSA.

Without more research in this area, academics and practitioners in PSA will continue to have limited knowledge about the factors that limit and facilitate the academia–practice disconnect (Tucker & Lowe, Citation2014). It is also necessary to unravel precisely how the current academia–practice disconnect has emerged (Daugherty et al., Citation2023).

This article examines how a serious academia–practice disconnect has developed in education and research related to central and local government accounting (CLGA) in Norway between 2010 and 2022. In just 12 years, academia has lost its position in education and research related to CLGA at Norwegian higher education institutions (HEIs). This is characterized by dramatic cuts in the number of CLGA courses offered, drops in the number of students taking CLGA courses, and diminishing research dedicated to CLGA. Soon, it is conceivable that there will be no graduates with CLGA knowledge emerging from Norwegian HEIs, nor academics doing research about CLGA. Hence, HEIs in Norway are becoming completely disconnected from CLGA practices. We realize that similar developments are taking place elsewhere. The Norwegian case, therefore, should act as a warning to other countries.

To analyse the developing academia–practice disconnect in the case of Norwegian CLGA, we mobilize the theory of path dependency, highlighting the transformative force of self-reinforcing institutional processes (Schreyögg & Sydow, Citation2011). We address the following research question:

What self-reinforcing institutional processes have contributed to the extinction of CLGA education and research in Norway and how?

Literature review and theoretical framework

Academia–practice disconnect in the field of PSA

Practitioners and academics have been described as coming from different planets (Tucker & Lowe, Citation2014). Unlike in fields such as medicine and engineering, this disconnect is widely observed in business administration, public administration and accounting (Bolton & Stolcis, Citation2003; Fraser et al., Citation2020; Daugherty et al., Citation2023). The academia–practice disconnect carries social and economic costs for society (Ghoshal, Citation2005; Ferraro et al., Citation2005; Parker et al., Citation2011; Wilkinson & Durden, Citation2015). For instance, it leads to graduates lacking essential skills (David et al., Citation2011) and research outputs that fail to enhance accounting practices (Inanga & Schneider, Citation2005) or benefit society at large (Fraser et al., Citation2020). Additionally, it diminishes research innovation and teaching quality (Van Helden & Argento, Citation2020).

The disconnect is generally attributed to existence of academic ‘echo chambers’, where academics focus on the development of an academic career in accordance with tenure policies at HEIs (Daugherty et al., Citation2023). However, within the field of PSA, this disconnect exhibits nuanced characteristics (Argento & van Helden, Citation2023; Heiling et al., Citation2023). For example PSA integrates topics not just from accounting but also public administration disciplines, focusing on a broad set of different tools beyond technical issues of financial accounting, including for example accountability, management control and performance management (Argento & van Helden, Citation2023). Yet, PSA research occupies a specialized academic niche, competing for attention alongside other disciplines and therefore facing the risk of marginalization over time (Argento & van Helden, Citation2023). The choice of research priorities and their relevance to practice depends on an HEI’s expectations and a researcher’s discretion (Tucker et al., Citation2020). Consequently, PSA academics may oscillate within the field or even shift entirely toward other research areas.

Furthermore, PSA research exhibits a tendency to shift focus away from addressing ‘technical’ accounting issues toward exploring the ‘social’ aspects of accounting. These social dimensions encompass behavioural, organizational, and societal elements (Ter Bogt & van Helden, Citation2012; Van Helden, Citation2019). By drawing insights from economics, political science and organizational disciplines, PSA research becomes interdisciplinary (Argento & van Helden, Citation2023). Understanding these ‘social’ aspects can assist practitioners in better comprehending the challenges within the accounting environment (Gomes et al., Citation2023).

However, technical aspects of PSA often vary by country, making them less appealing to the international research community compared to social accounting issues. Paradoxically, it is often the ‘technical’ aspects of accounting that seemingly hold immediate relevance for practitioners, rather than its social dimensions (Mitchell, Citation2002; Ter Bogt & van Helden, Citation2012). A shift away from the ‘technical’ toward the ‘social’ can contribute to a ‘relevance loss’ in academic research when researchers fail to formulate pertinent research questions for practical application (Inanga & Schneider, Citation2005; Ter Bogt & van Helden, Citation2012).

In addition, PSA academia can impact practice through education, although this link is not always apparent (Heiling, Citation2020; Heiling et al., Citation2023). Many countries face challenges in capacity-building programmes and designing academic curricula to support the necessary capacities in PSA (Grossi et al., Citation2023). However, PSA curricula at HEIs tend not to change quickly enough to address emerging practical problems (Pericolo et al., Citation2023). Moreover, PSA topics appear to be less relevant for research universities and are often taught in lower-level degree programmes (Reichard et al., Citation2023). In some countries, the focus on teaching PSA is reduced due to pressure to adopt private sector accounting practices driven by New Public Management reforms (Hoque, Citation2023).

Finally, PSA research can be valuable for practice, but not always in the way academics are encouraged to produce it (Talbot & Talbot, Citation2015). Academia has largely been unable to collaborate effectively with accounting professional bodies (Tucker & Schaltegger, Citation2016). However, the use of research results requires active engagement and interaction between academics, policy-makers and other stakeholders (Talbot & Talbot, Citation2015, p. 194). Therefore, academia can enhance knowledge creation for PSA practices by improving networking and engagement with stakeholders (Van Helden et al., Citation2010).

To summarize, PSA academia faces pressures to demonstrate its relevance to practice. Still, understanding this research–practice gap necessitates a better comprehension of how these pressures have developed over time (Tucker & Lowe, Citation2014; Daugherty et al., Citation2023). Different national contexts should be explored, as the disconnect can transcend geographic boundaries (Ahrens & Chapman, Citation2000; Messner et al., Citation2008; Tucker & Schaltegger, Citation2016). This study investigates the processes leading to an increasing disconnect between CLGA academia and practice in the case of Norway.

Theoretical framework: organizational path-dependence and self-reinforcing processes

The decline and disappearance of CLGA education at HEIs can be explained by path-dependence and self-reinforcing mechanisms, which derive from the collective actions of various institutions. Sydow et al. (Citation2009) demonstrate that organizations can lose their flexibility and become locked into a path-dependency due to self-reinforcing mechanisms, leading to escalating situations with unforeseen consequences (Schreyögg & Sydow, Citation2011).

Path-dependence involves a three-stage process (Schreyögg & Sydow, Citation2011):

-

In the pre-formation stage, institutional actors typically have a broad scope of actions and variation in practices. However, certain ‘small events’ (referred to as ‘critical junctures’)—such as decisions or actions taken by specific actors—can unintentionally initiate a self-reinforcing process.

-

The formation stage marks the emergence of a new regime, resulting in the establishment of a dominant action pattern among actors. Other potential alternative patterns are disregarded as this central pattern evolves over time, becoming increasingly difficult to reverse.

-

In the lock-in stage, all actors in the field become further constrained and locked into the dominant pattern. Organizational members find it challenging to see beyond this path, leading to a state of ‘entrapment’ with the risk of a downward spiral (for example Sydow & Schreyögg, Citation2013).

There are several typical organizational self-reinforcing mechanisms (Schreyögg & Sydow, Citation2011), including co-ordination effects, complementarity effects and adaptive expectation effects. The co-ordination self-reinforcing mechanism is based on the benefits of rules-guided behaviour (North, Citation1990). When many actors adhere to the same rules or routines, co-ordination costs are reduced. The more actors follow the same rules, the more attractive this behaviour becomes. Next, the complementarity self-reinforcing mechanism arises when separate but interrelated resources, rules, or practices interact (Schreyögg & Sydow, Citation2011). These interactions can create additional surplus, including cost savings by eliminating practices significantly deviating from established norms. Finally, the adaptive expectation self-reinforcing mechanism arises when organizations adopt certain practices in response to the expectations of others. If it is expected that others will follow a particular path, organizations may choose to align with that path, hoping to be on the winning side. Legitimacy seeking behaviour or signaling reinforces this process, with those not following this logic being labeled as outsiders.

Once an organization is locked into a path, breaking free becomes challenging (Sydow & Schreyögg, Citation2013). Actors often develop specific causal explanations (narratives) that construct a self-sustaining frame of reference. This prevents the organization from questioning the principles underlying past developments (Geiger & Antonacopoulou, Citation2009). To break this cycle, any intervention must overcome these ‘defensive routines’ (Sydow & Schreyögg, Citation2013).

Research context and method

The developments in central and local government financial accounting education and research between 2010 and 2022, along with the institutions involved, serve as the empirical context for this study. CLGA in Norway is our focus—both are unique hybrid accounting models that combine elements from both cash and accrual accounting systems. Notably, CLGA in Norway differs significantly from private sector accounting practices (for example Mauland & Aastvedt, Citation2008; Gårseth-Nesbakk, Citation2008; Mauland & Mellemvik, Citation2010; Gårseth-Nesbakk, Citation2011; Gårseth-Nesbakk & Mellemvik, Citation2011). The hybrid nature of CLGA has consistently posed challenges for its preparers and users (Mellemvik et al., Citation2000; Gilberg & Gårseth-Nesbakk, Citation2019). Despite attempts in 2003 and 2015 (when the Andreassen Committee and Børmer Committee respectively published official reports) there have been no significant efforts to effectively alter the CLGA model—for instance, by aligning it with private sector accounting rules or International Public Sector Accounting Standards (IPSASs). Unlike Norwegian private sector accounting and auditing, which adopted EU directives, CLGA has remained unaffected by these legislative changes. Standard-setters and practitioners in the CLGA domain have primarily focused on incremental refinements. They have often integrated solutions from other accounting models to address immediate technical accounting issues and financial information needs without altering the fundamental model itself. Notably, academia played a limited role in shaping these changes, as none of the board members or the 10 technical committee members of the Norwegian standard-setting body for the municipal sector (GKRS), established in 2000, were recruited from academia. In contrast, the chair of the standard-setting body for the private sector, and three of the nine technical committee members, including its chair, were recruited from academia.

Mastering the hybrid CLGA in Norway requires specific education, along with on-the-job training during and after completing this education. Its uniqueness, combined with the need in the public sector for specialists with this education, should theoretically incentivize academic institutions to maintain CLGA education and research offerings. However, the case of Norway reveals the opposite development.

To better understand this trend, evidence was collected documenting the developments in CLGA education and research over 12 years. The empirical part of this article relies on analysing triangulated data from various sources, including databases from the Norwegian Directorate for Higher Education and Skills (HKDIR), the National Library, and HEIs’ websites. This data allows an analysis of the changing scope of CLGA education, as well as the evolving landscape of CLGA research. Additionally, relevant publications related to CLGA in Norway were reviewed.

In addition, we found five academics, whom we identified as the most relevant and knowledgeable respondents. These experts have been involved in teaching CLGA in Norway for many years and were asked to comment on the development of CLGA in Norway based on the path-dependence theory (see ). As well, the authors of this article have reflected on their own extensive involvement in CLGA education, practice, and research spanning over a decade. In addition to analysing feedback from respondents, documents, and databases, the authors have employed memory work as a supplementary methodological approach. Memory work focuses on individual written memories and their collective analysis and theorizing, especially when researchers reflect on their own engagement in the field.

Table 1. Questions put to academics involved in PSA teaching in Norway.

The memory work is not devoid of structured processes for collecting and analysing evidence. It involves three phases for the researchers involved: individual reflection, collective reflection and further theorization of the materials (Johnson et al., Citation2018; Katila et al., Citation2020). In this context, the authors focused on written individual memories related to their engagements in practice, teaching, and research of CLGA during the period 2010 to 2022, followed by collective analysis and theorizing. Over a 10-month period, we held approximately 10 meetings. Three key topics emerged from writing individual perceptions: historical developments in CLGA; engagement in different CLGA fora and teaching experience. This process facilitated the construction of logical feedback loops to understand dynamics within the field (Sastry, Citation1998) of CLGA. Subsequently, individual narratives were presented, discussed, and synthesized into a generative narrative that sheds light on the ‘self-reinforcing’ patterns of CLGA development in Norway.

Empirical findings

Towards extinction of CLGA education in Norway

provides an historical overview of the number of CLGA courses offered by Norwegian HEIs from 2010 to 2022. Initially, the number of courses remained stable during the period 2010 to 2013, with a notable 50% increase in 2014. However, after 2014, a persistent decline occurred, plummeting from 74 courses in the peak year of 2014 to only 18 courses in 2022. Even HEIs that were previously leaders in offering CLGA courses (such as the University College of Innlandet) have significantly reduced their portfolio over time. Only seven out of 14 HEIs provide CLGA education in 2022 and their course offerings have declined significantly.

Table 2. Number of CLGA-related courses at different educational levels at Norwegian HEIs.

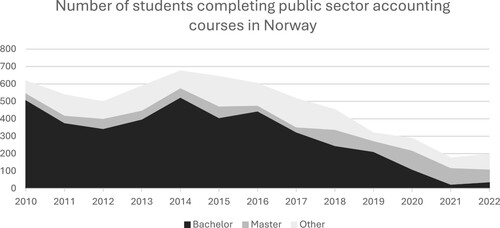

presents an overview of the number of students who have taken and completed CLGA education during the period 2010 to 2022. There is a dramatic reduction at the bachelor level since 2016 and a slight increase at the master level and other non-degree courses, which do not adequately compensate for the decline in bachelor students.

Figure 1. Number of students who have completed CLGA courses at Norwegian HEIs. Source: Compiled from data provided by the Norwegian Directorate for Higher Education and Skills (HKDIR).

The following sections provide the analysis of several processes that have shaped the changes in CLGA education in Norway.

Regulatory changes: A shift toward focusing on private sector needs

One significant process relates to changes in the external institutional environment for HEIs and how various professional accounting bodies have responded to these changes in terms of CLGA education. Professional accounting associations have emphasized an increasing need for candidates with general accounting and auditing skills for the private sector, with educational requirements for certification as a state authorized public accountant. Historically, in Norway, there were two types of auditor/accountant degrees and certifications: one at the bachelor level and one at the master level. Many Norwegian HEIs could only offer a bachelor’s degree in auditing and accounting, qualifying students to be certified as registered public accountants. The master’s degree in auditing and accounting was offered by only two HEIs—the Norwegian School of Economics (NHH) and BI Business School—qualifying graduates to become state authorized public accountants.

In 2011, the Norwegian Ministry of Education and Research initiated the discussion in relation to changes being made to the national framework for the bachelor’s degree in auditing and accounting. The rationale behind this proposal was a stronger need for candidates with business economics competences and knowledge to become more familiar with IFRS due to Norway’s commitment to EU’s accounting regulation, effective from 2005 (EC, Citation2002) and the audit directive, effective from 2008 (EC, Citation2006). The development of the national framework was co-ordinated by UHR Economics and Administration (NRØA), a disciplinary strategic unit subordinated Universities Norway (UHR). In the NRØA proposal, the CLGA course was allocated only five ECTS (credits according to The European Credit Transfer and Accumulation System) within the compulsory package of accounting and auditing courses, which totaled 95 ECTS in a three-year bachelor education in Norway (equivalent to 180 credits).

The Local Government Accounting Professional Association (Norges Kemner- og Kommuneøkonomers forbund (NKKF), Citation2012) expressed concerns about the development of accounting education in Norway. According to their statement (our translation):

NKKF has long been concerned about the content of education. The trend has shifted towards placing less emphasis on subjects relevant for work in the public sector. In our opinion, the proposed education framework has inadequately addressed the need for education that qualifies individuals to work in both the private and public sectors. Local governments and central government agencies operate with different purposes and principles for accounting and management control than private companies. Therefore, education must provide the necessary knowledge for students to be qualified to work in both the private and public sectors.

In 2016, the Ministry of Higher Education and Research established an expert committee tasked with assessing the proposal to offer auditor education exclusively at the master’s level. After receiving the expert committee’s report, the ministry invited the NRØA to consider practical aspects. All Norwegian HEIs were involved in this process.

While the course content needed to be aligned with EU requirements for this type of education, the requirements were broadly defined, allowing for some interpretation and discretion. Although the bachelor degree typically included at least one separate compulsory course in CLGA, the expert committee’s course package recommendation did not include a CLGA course. During an NRØA meeting attended by one of the authors, various ideas were discussed regarding a transition to a master’s degree. However, little attention was given to the implicit sidelining of CLGA. One member raised concerns, arguing that a CLGA course would align with EU requirements for course content. Unfortunately, no one else advocated for CLGA during that meeting, resulting in its exclusion from the national master’s education in accounting and auditing. Additionally, one of the five CLGA academics we interviewed, who was a member of the Universities Norway (UHR) subordinate unit for accounting and auditing, had addressed the need to include a PSA course in the master’s degree in accounting and auditing. This initiative was, however, turned down by the other members of the unit, all of whom were academics.

HEI responses to changing regulations – CLGA is of low strategic importance

As a result, the previous oligopoly of two universities providing the master’s degree in accounting and auditing came to an end, and some of the HEIs that were previously offering a bachelor’s programme in accounting and auditing started to offer a master’s programme in accounting and auditing instead (a total of nine HEIs in 2022).

The five CLGA academics interviewed, when asked to identify the most significant event contributing to the reduction in CLGA courses offered by HEIs, unanimously identified that the shift from a bachelor’s programme to a master’s programme was the key factor. Consequently, most HEIs that had previously offered CLGA courses discontinued them, as they were no longer compulsory at either the bachelor’s or master’s levels. The gradual decline in the number of CLGA courses coincided with the ongoing hearing process in 2016–2017, suggesting that HEIs represented at NRØA meetings likely recognized that CLGA courses would have no future.

An associated issue relates to teaching capacity. To develop and offer new programmes at HEIs, existing capacities of university lecturers and researchers were redirected from other programmes, including CLGA courses. New education incorporated regulations applicable to private companies, covering areas such as company law, the Accounting Act, good accounting practice, IFRS, the Act on Auditing and Auditors, and the legal auditing standard known as ‘good auditing practice’. CLGA courses typically cover local government law, CLGA legislation, ‘good municipal accounting practice’ (the auditing provisions of the Local Government Act) (Gilberg & Bardal, Citation2019). However, the internal lack of teaching resources and the non-mandatory status of CLGA courses led to their discontinuation in the curriculum, even as electives.

Conversations with CLGA academics also reveal that capacity constraints are only part of the story. Remarkably, CLGA has never been on the ‘strategic map’ for most of the HEIs in Norway. As one respondent stated: ‘Those in different strategic positions believed that this is what you can learn in practice’. Another respondent said: ‘Education in CLGA has never been a priority for [my HEI]. The offering was based on my personal interest’. This sentiment was echoed by another respondent: ‘[My HEI] did nothing special in creating the educational offer but allowed me to start and deliver the course. Although I intend to continue with the course, I’ve noticed similar courses being discontinued elsewhere … It’s regrettable but not surprising’.

Therefore, in many institutions, the availability of CLGA courses depended heavily on individual academic interests in the CLGA field, rather than institutional strategies. Some HEIs employed academics who were knowledgeable and passionate about CLGA (referred to as ‘academic enthusiasts’). Other HEIs lacked academic staff capable of teaching CLGA. Hence, teaching CLGA was outsourced to invited practitioners, thus bringing knowledge of the public sector into the HEIs rather than providing input from the HEIs to PSA practitioners. This also explains the limited number of academics available for us to interview. Consequently, the removal of the compulsory requirement to teach CLGA was met with approval from most HEI managers, further weakening the prioritization of CLGA in institutional education and research strategies.

Historically, there were active researcher communities addressing practical and theoretical CLGA problems in Norway (Bergevärn et al., Citation1995; Mellemvik & Pettersen, Citation1998; Mellemvik et al., Citation2005). For instance, an action research project (commonly known as the ‘Bergen experiment’) was conducted in the 1980s to address the issue of politicians using accounting reports. In the 1990s, several Norwegian CLGA researchers became members of the Comparative International Governmental Accounting Research (CIGAR) network, contributing to developments in Norwegian CLGA research that were accessible internationally. This research has explored various aspects of CLGA, including its dependence on central government regulation and the specific needs it serves.

However, over the years, the role of CLGA academic enthusiasts has faded, resulting in a decline in academic research output related to CLGA. For instance, provides an overview of PhD theses related to accounting from 2000 to 2022.

Table 3. The number of PhD theses and international publications in international journals and books in the field of CLGA.

During this period, the number of PhD theses in the field of accounting and auditing increased. However, out of 54 dissertations only nine were specifically related to CLGA, while six related to other aspects of PSA (for example accounting in healthcare). Interestingly, most of the CLGA-related dissertations focused on CLGA in other countries (for example Russia, Nepal, Sri Lanka, Pakistan), with only one dissertation specifically addressing CLGA in Norway. Notably, since 2007, there have been no PhD candidates in the field of Norwegian CLGA across all business schools in Norway, and no PhD dissertations related to CLGA have been published in Norway since 2018.

An overview of the publications by researchers in the field of CLGA from Norwegian HEIs in international journals () also demonstrates a decline in the number of publications over the years. While the number of publications related to different aspects of PSA remains stable and even growing among Norwegian HEIs, it appears that previously active researchers in CLGA have ceased conducting research and publishing in this field. Their research interests have shifted to other disciplines or from the more ‘technical’ focus of CLGA toward the ‘social’ aspects of PSA. Recent publications increasingly address such topics as accounting for smart cities, strategic management, management control, and performance management in public sector organizations.

Recruiting new academics to the CLGA research field presents challenges. One potential reason is that arguing for a PhD position in CLGA becomes difficult when CLGA is not a priority on an HEI’s strategic agenda. Additionally, language barriers pose obstacles for international PhD candidates who cannot speak Norwegian. These trends clearly indicate a waning academic interest in CLGA in Norway. The number of academics capable of conducting research and teaching CLGA is now diminishing.

In 2022 only five academics actively engage in research and provide bachelor/master level courses, including CLGA at the seven HEIs that still offer CLGA courses. When these CLGA ‘enthusiasts’ retire, there will be no academic successors available to teach and conduct research in the field of CLGA.

Potential consequences – towards hidden accounting harmonization?

If these trends continue, the most pessimistic outcome is that, in five years, there will be no HEIs offering CLGA courses in Norway and no students enrolling in CLGA courses. This potential outcome would result in lost opportunities for HEIs to educate a critical mass of students who are properly qualified to work with the existing CLGA model. Graduating students will therefore lack the necessary knowledge of the peculiarities of both the public sector in general and CLGA in particular (NKKF, Citation2012). Some of our respondents expect that this situation will lead to a ‘silent accounting harmonization’, following a degeneration of CLGA due to lack of external input.

Several accounting solutions adopted by CLGA regulators in Norway have already been ‘borrowed’ from private sector accounting. As time passes, maintaining current accounting practices in the Norwegian central and local governments will become increasingly challenging without access to qualified personnel. Since there will be no accountants and auditors who are familiar with the peculiarities of Norwegian CLGA, many professionals will need to be recruited from the private sector. Consequently, CLGA is likely to gradually converge toward private sector accounting. This shift poses significant implications for the future of accounting practices in Norway.

Concluding discussion

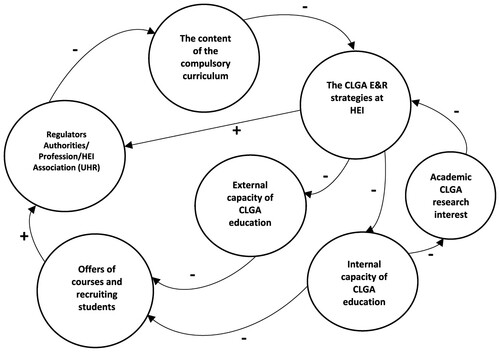

There have been several processes that have shaped changes in CLGA education in Norway towards near extinction. summarizes those processes, as well as their self-reinforcing nature.

‘Entrapment’ – reduced CLGA education offer as a result of adoption of EU rules

The theory of path-dependence is useful in explaining the development of CLGA education in Norway. The three stages of organizational path-dependence were clearly visible (Schreyögg & Sydow, Citation2011). In the pre-formation stage (2010–2014) various HEIs offered CLGA courses, reflecting a diverse landscape of CLGA education. In the formation stage (2013–2020) there was a reduction in CLGA education offerings by HEIs. Finally, in the lock-in stage (around 2020), we saw the historically lowest number of CLGA courses being offered by HEIs. The critical juncture initiating the formation stage appears to be related to the adoption of EU rules, as well as the subsequent abandonment of the bachelor’s programme in accounting and auditing with compulsory CLGA courses. These developments have significantly shaped the trajectory of CLGA education in Norway.

Self-reinforcing mechanisms: institutional co-ordination, complementarity, and adaptive expectations

Applying the theoretical framework of Schreyögg and Sydow (Citation2011) reveals self-reinforcing processes leading to a negative spiral. Initially, there was a co-ordination effect among the institutional actors involved in regulation. The new EU regulation was adapted to the Norwegian context by establishing a new rule of the game, which was that CLGA courses were not compulsory. HEIs therefore removed CLGA education from their curriculum partly because it allowed them to reduce the diversity of programmes offered. As well, in a world where the private sector’s needs for accounting and auditing professionals are clearly articulated, it was more attractive for HEIs to abandon CLGA in favour of a master’s in accounting and auditing. The UHR Economics and Administration—an institution expected to reflect academic diversity—functioned as a co-ordination centre between the HEIs, ministries, and the accounting profession to facilitate the adoption of this new rule. In this case it seemed to let the majority decide without paying much attention to the elimination of PSA course content or the impact of such a decision.

The elimination of CLGA education also had complementary effects in terms of cost savings. By discontinuing teaching practices that had begun to deviate significantly from established organizational capabilities, HEIs could save money. These capabilities were increasingly focused on providing accounting and auditing education at the master’s level, which was primarily relevant to the private sector. This is a ‘negative’ complementarity because HEIs could save costs by outsourcing the teaching of CLGA courses to practitioners and/or reducing support to academic individuals in the CLGA field, thereby saving money in an area of education that was no longer compulsory. Since CLGA courses were no longer mandatory and resources were lacking, reducing CLGA education was presumably the most efficient response by HEIs.

Finally, there was also an adaptive expectation effect in that HEIs seemed to have adjusted their preferences to reduce CLGA offerings in response to others’ expectations. Organizational narratives could have played a significant role in shaping adaptive expectations (Geiger & Antonacopoulou, Citation2009). CLGA was no longer considered important because it could be handled by practice itself. Consequently, there was no academic value in engaging in CLGA education. Warnings from public sector institutions like NKKF were ignored. In this way, adaptive expectations have created a web of related narratives, becoming a self-referential frame of reference (Foucault, Citation1980, p. 132).

Academia–practice disconnect development due to self-reinforcing processes: a ‘double marginalization’ of CLGA?

Our study demonstrates that the extinction of CLGA education highlights a disconnect between academia and practice in terms of the CLGA needs for educated accounting practitioners. Meanwhile, HEIs are increasingly prioritizing the education of accounting practitioners for the private sector. Previous literature suggests that this academia–practice disconnect can develop because academia becomes trapped in its self-created institutional structures (Wilkinson & Durden, Citation2015). We add to this literature by demonstrating that the academia–practice disconnect can be subject to self-reinforcing institutional processes, leading to a particular path-dependence and entrapment (Schreyögg & Sydow, Citation2011). Our contribution lies in shedding light on how this disconnect has developed and widened over time (Ahrens & Chapman, Citation2000; Messner et al., Citation2008; Tucker & Schaltegger, Citation2016; Daugherty et al., Citation2023).

Regarding the academia–practice disconnect in the field of PSA, our study also contributes to Argento and van Helden (Citation2023) and Gebreiter (Citation2022) by demonstrating that self-reinforcing processes can lead to a ‘double-marginalization’ of CLGA education and research—ultimately resulting in its extinction. First, CLGA is marginalized in favour of teaching private sector accounting, leading to the marginalization of CLGA educators and research (Heiling et al., Citation2023; Hoque, Citation2023). Second, CLGA is further marginalized by focusing on research and education related to the ‘social’ rather than ‘technical’ aspects of CLGA (Ter Bogt & van Helden, Citation2012).

Implications

The extinction of CLGA education at HEIs in Norway will deprive the country’s public sector organizations of the opportunity to hire graduates who are knowledgeable about the nuances and peculiarities of the public sector. As CLGA academics shift their focus to other educational and research areas, society and public sector practitioners are likely to be the biggest losers. This fading academic interest means that PSA theorizing may vanish, critical voices may become scarce, relevant textbooks may cease to exist, and formalized education may not be provided at all. All training and teaching will have to be done locally at public institutions. Accounting education will typically be reduced to meeting continuous education requirements for public sector auditors and accountants. This technical training in accounting will continue to be provided by the professional bodies. Without external input from academia, we anticipate that the CLGA education environment will resemble a fish tank rather than an open ocean. It may feel like a safe environment for practitioners, but will lead to the aforementioned degeneration of CLGA.

We are not only concerned that this will have significant implications for CLGA quality, but also supervision, enforcement, accountability, transparency, and ultimately democracy. In a case when the top-down reforms in CLGA in Norway are impossible, and the self-reinforcing processes are dominating the institutional development of academia in the field of PSA, what options do academia have?

Sydow et al. (Citation2009) discuss whether organizations can escape entrapment in organizational paths and concluded that the same actors who led organizations to lock-in will be unable to contribute to unlocking. Instead, there is a need to interrupt the logic of the self-reinforcing patterns by reflecting on the drivers that led to this development. Similarly, Wilkinson and Durden (Citation2015) argue that, to break the path, radical changes in institutional structures are needed, not just incremental changes that offer extremely limited prospects.

One way to reverse the entrapment of CLGA education and research is to rethink the way academia and HEIs collaborate with practitioners (Van Helden et al., Citation2010; Talbot & Talbot, Citation2015). For instance, academia can strengthen its knowledge creation for accounting practices in the public sector by focusing on executive teaching and networking with relevant stakeholders to cope with marginalization (Van Helden et al., Citation2010). CLGA academics need to develop a role as ‘context ambassadors’ (Antipova & Bourmistrov, Citation2013) to address problems that matter to practitioners, avoiding the ‘loss before translation’ problem when selecting relevant research topics for practitioners (Ter Bogt & van Helden, Citation2012). As the need for postgraduate studies to strengthen the competence of professionals in PSA increases (Falivena et al., Citation2023; Schuler et al., Citation2023), there should be a way to reverse entrapment by developing courses for practitioners outside formal degree structures.

This could be achieved by changing the way accounting courses are provided—for example by making them more flexible and easily accessible. Smaller courses would be easier to sign up for, whether they are organized as digital courses or in other ways that better suit participants’ needs. The use of digital courses would broaden access to new learning arenas for practising central and local government accountants. Since practising accountants often have difficulty attending degree-based programmes at the bachelor’s and master’s levels, small study programmes or course modules based on ‘micro’ credentials/degrees (including a set of micro-courses up to 2.5 ECTS each) would be a new way to extend academia’s reach.

Micro-credentials can contribute to day-to-day professional accounting training and education, stimulating creative and critical thinking and training practising accountants as potential change agents (Al-Beraidi & Rickards, Citation2006; Bourmistrov, Citation2020). Micro-courses can bridge the existing academia–practice disconnect. In the long term, these micro-credentials/degrees and courses can enable PSA academia in Norway to regain its relevance to CLGA practices. The establishment of such courses can serve as a way out of the current negative self-reinforcing development trend toward extinction—creating renewed interest in the CLGA education and research field, stimulating new recruitment of teachers, and fostering fresh research activities.

Acknowledgements

The authors express their gratitude to Senior Adviser Bjarne Mundal at the Norwegian Directorate for Higher Education and Skills (HKDIR) for facilitating access to the necessary data. We also extend our thanks to the researchers who provided insightful feedback on an earlier version of this article during the 16th Comparative International Government Accounting Research (CIGAR) workshop held in Cottbus/Berlin, 21–23 September 2022. This research is part of the TRANSACT project, supported by the Research Council of Norway (RCN), grant number 301717. Our appreciation also goes to the anonymous reviewers and the CIGAR/PMM editorial team for their constructive comments and suggestions, which have significantly enhanced our article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Anatoli Bourmistrov

Anatoli Bourmistrov is Professor of Accounting/Management Control at Nord University Business School, Norway. His research covers public sector accounting and performance management reforms, management control innovations in the public and private sectors, relationships between information and managerial attention, and issues of long-term planning via the use of scenarios. He received the Outstanding Paper award in the 2018 Emerald Literati Awards for the most exceptional work published in the Journal of Accounting & Organizational Change for 2017 and the David Solomons Prize for the best paper in management accounting research for 2013.

Brynjar Gilberg

Brynjar Gilberg is Associate Professor of Auditing at Nord University Business School, Norway, and a state authorized public accountant. He worked for many years at KPMG in Oslo and in Silicon Valley. He then worked as a special advisor at the Financial Supervisory Authority of Norway, in charge of establishing and conducting audit firm inspections, after the EU Statutory Audit Directive came into force in 2006 and held management positions in international organizations such as IFIAR and EAIG (now CEAOB). Before joining academia, he was Auditor General of Nordland.

Levi Gårseth-Nesbakk

Levi Gårseth-Nesbakk is Professor of Accounting at Nord University Business School, Norway. His research mainly covers the application of accrual accounting in the public sector; accounting representations; hybridity in accounting models; accounting harmonization; and fiscal sustainability.

References

- AACSB. (2022). Research that matters: an action plan for creating business school research that positively impacts society. https://www.aacsb.edu/-/media/publications/research-reports/research-that-matters.pdf?la=en&hash=C46DC15423E49338D14A0F7F947BA04D98CD7FAF.

- Ahrens, T., & Chapman, C. S. (2000). Occupational identity of management accountants in Germany and Britain. European Accounting Review, 9(4), 477–498.

- Al-Beraidi, A., & Rickards, T. (2006). Rethinking creativity in the accounting profession: to be professional and creative. Journal of Accounting and Organizational Change, 2(1), 25–41.

- Antipova, T., & Bourmistrov, A. (2013). Is Russian public sector accounting in the process of modernization? An analysis of accounting reforms in Russia. Financial Accountability & Management, 29(4), 442–478.

- Argento, D., & van Helden, J. (2023). Are public sector accounting researchers going through an identity shift due to the increasing importance of journal rankings? Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 96, 102537.

- Bergevärn, L. E., Mellemvik, F., & Olson, O. (1995). Institutionalization of municipal accounting—a comparative study between Sweden and Norway. Scandinavian Journal of Management, 11(1), 25–41.

- Bolton, M. J., & Stolcis, G. B. (2003). Ties that do not bind: Musings on the specious relevance of academic research. Public Administration Review, 63(5), 626–630.

- Bourmistrov, A. (2020). From educating agents to change agents: experience of using foresight in accounting education. Journal of Accounting & Organizational Change, 16(4), 607–612.

- Campbell, A., Lindsay, D. H., & Foote, P. S. (2000). Does a government/not-for-profit program requirement improve CPA exam pass rates? The Journal of Government Financial Management, 49(2), 38.

- Daugherty, B. E., Dickins, D., Pitman, M. K., & Tervo, W. A. (2023). Perceived obstacles to conducting and publishing practice-relevant academic accounting research. Accounting and the Public Interest, 1–32.

- David, F. R., David, M. E., & David, F. R. (2011). What are business schools doing for business today? Business Horizons, 54(1), 51–62.

- EC. (2002). Regulation (EC) No 1606/2002 on the application of international accounting standards. European Parliament and Council. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex%3A32002R1606.

- EC. (2006). Directive 2006/43/EC on statutory audits of annual accounts and consolidated accounts. European Parliament and Council. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:32006L0043.

- EU. (2014). Directive 2014/56/EU. Amending Directive 2006/43/EC on statutory audits of annual accounts and consolidated accounts. European Parliament and Council. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32014L0056&from=EN.

- Falivena, C., Adam, B., Brunelli, S., Heiling, J., & Karatzimas, S. (2023). New development: A prototype framework to assess the coverage of financial management topics in MPA/MPM programmes. Public Money & Management, 43(7), 75.

- Ferraro, F., Pfeffer, J., & Sutton, R. I. (2005). Economics, language and assumptions: how theories can become self-fulfilling. Academy Management Review, 30, 8–24.

- Foucault, M. (1980). Truth and power. In C. Gordon (Ed.), Power/knowledge: Selected interviews and other writings (pp. 109–133). Pantheon Books.

- Fraser, K., Deng, X., Bruno, F., & Rashid, T. A. (2020). Should academic research be relevant and useful to practitioners? The contrasting difference between three applied disciplines. Studies in Higher Education, 45(1), 129–144.

- Gårseth-Nesbakk, L. (2008). Accounting at local government level in Norway: for the accounting elite only. In S. Pozzoli (Ed.), Local authorities’ accounting and financial reporting. Trends and techniques in a multinational perspective (pp. 113–123). Franco Angeli.

- Gårseth-Nesbakk, L. (2011). Accrual accounting representations in the public sector—A case of autopoiesis. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 22(3), 247–258.

- Gårseth-Nesbakk, L., & Mellemvik, F. (2011). The construction of materiality in government accounting: a case of constraining factors and the difficulties of hybridization. Financial Accountability & Management, 27(2), 195–216.

- Gebreiter, F. (2022). A profession in peril? University corporatization, performance measurement and the sustainability of accounting academia. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 87, 102292.

- Geiger, D., & Antonacopoulou, E. (2009). Narratives and organizational dynamics: Exploring blind spots and organizational inertia. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 45(3), 411–436.

- Ghoshal, S. (2005). How bad management theories are destroying good management practice. Academy of Management Education and Learning, 4, 75–91.

- Gilberg, B., & Bardal, K. G. (2019). Revisjonskvalitet og bestillerkompetanse. In L. Gårseth-Nesbakk, K. M. Baksaas, & T. Gustavsen (Eds.), Trender og utfordringer i regnskap og revisjon (pp. 165–178). Fagbokforlaget.

- Gilberg, B., & Gårseth-Nesbakk, L. (2019). Kommunelovens krav til økonomisk bærekraft - hvordan ivaretar kommuneregnskapet en måling av økonomisk bærekraft? In L. Gårseth-Nesbakk, K. M. Baksaas, & T. Gustavsen (Eds.), Trender og utfordringer i regnskap og revisjon (pp. 195–212). Fagbokforlaget.

- Gomes, P., Teixeira, C., & Azevedo, G. (2023). Debate: Integrating new perspectives in public sector accounting education (PSAE). Public Money & Management, 43(7), 727–728.

- Grossi, G., Steccolini, I., Adhikari, P., Brown, J., Christensen, M., Cordery, C., & Vinnari, E. (2023). The future of public sector accounting research. A polyphonic debate. Qualitative Research in Accounting & Management, 20(1), 1–37.

- Heiling, J. (2020). Time to rethink public sector accounting education? A practitioner’s perspective. Journal of Public Budgeting, Accounting & Financial Management, 32(3), 505–509.

- Heiling, J., Adam, B., Jorge, S., & Karatzimas, S. (2023). Editorial: PMM CIGAR theme: Public sector accounting—educating for reform challenges. Public Money & Management, 43(7), 722–724.

- Hoque, Z. (2023). New development: New public management values and public sector accounting education in Australia—A ‘reflection-in-action’ perspective. Public Money & Management, 43(7), 750–754.

- Inanga, E. L., & Schneider, W. B. (2005). The failure of accounting research to improve accounting practice: a problem of theory and lack of communication. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 16(3), 227–248.

- Johnson, C. W., Kivel, B. D., & Cousineau, L. S. (2018). The history and methodological tradition(s) of collective memory work. In C. W. Hohnson (Ed.), Collective memory work (pp. 3–26). Routledge.

- Karatzimas, S., Heiling, J., & Aggestam-Pontoppidan, C. (2022). Public sector accounting education: A structured literature review. Public Money & Management, 42(7), 543–550.

- Katila, S., Laamanen, M., Laihonen, M., Lund, R., Merilainen, S., Rinkinen, J., & Tienari, J. (2020). Becoming academics: Embracing and resisting changing writing practice. Qualitative Research in Organizations and Management: An International Journal, 15(3), 315–330.

- Mauland, H., & Aastvedt, A. (2008). Mission impossible or an obvious option – provisions and contingent liabilities in Norwegian LGA. In S. Jorge (Ed.), Implementing reforms in public sector accounting (pp. 279–297). University of Coimbra.

- Mauland, H., & Mellemvik, F. (2010). LGA in Norway: Central norms create confusing information at the local level. In A. Bac (Ed.), International comparative issues in government accounting. Springer.

- Mellemvik, F., Bourmistrov, A., Mauland, H., & Stemland, J. (2000). Regnskap i offentlig (kommual) sektor: behov for en ny modell. HBO-rapport, 9), Høgskolen i Bodø.

- Mellemvik, F., Gårseth-Nesbakk, L., & Olsson, O. (2005). Northern lights on public sector accounting research – dominate traits in 1980-2003. In S. Jönsson, & J. Mouritsen (Eds.), Accounting in Scandinavia: the northern lights (pp. 299–319). Copenhagen Business School Press.

- Mellemvik, F., & Pettersen, I. J. (1998). Norway–a hesitant reformer? In O. Olson, J. Guthrie, & C. Humphrey (Eds.), Global Warning: Debating International Developments in New Public Financial Management (pp. 185–218). Cappelen Akademisk Forlag.

- Messner, M., Becker, A., Schäffer, U., & Binder, C. (2008). Legitimacy and identity in Germanic management accounting research. European Accounting Review, 17(1), 129–159.

- Mitchell, F. (2002). Research and practice in management accounting: improving integration and communication. European Accounting Review, 11(2), 277–89.

- NKKF. (2012). Høring – Utkast til Forskrift om Rammeplan for Bachelor i Regnskap og Revisjon. Norges Kemner- og Kommuneøkonomers forbund (NKKF). https://nkkf.no/edokumenter/kommuneregnskap/horing_utkast_til_forskrift_om_rammeplan_for_bachelor_i_regnskap_og_revisjon_nkk.pdf.

- North, D. C. (1990). Institutions, institutional change and economic performance. Cambridge University Press.

- Novin, A., Meeting, D., & Schlemmer, K. T. (1997). Educating future government accountants. The Journal of Government Financial Management, 46(1), 12.

- Parker, L. D., Guthrie, J., & Linacre, S. (2011). The relationship between academic accounting research and professional practice. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 24(1), 5–14.

- Pericolo, E., Fedele, P., Iacuzzi, S., Pauluzzo, R., & Garlatti, A. (2023). Public sector accounting education: international trends and Italian curricula. Public Money & Management, 43(7), 731–740.

- Reichard, C., Küchler-Stahn, N., & Siegel, J. (2023). Education in public sector accounting at higher education institutions in Germany. Public Money & Management, 43(7), 741–749.

- Sastry, A. (1998). Archetypal self-reinforcing structures in organizations. Proceedings of the 16th International Conference of the System Dynamics Society, Quebec.

- Schreyögg, G., & Sydow, J. (2011). Organizational path dependence: A process view. Organization Studies, 32(2), 321–335.

- Schuler, C., Grossi, G., & Fuchs, S. (2023). New development: The role of education in public sector accounting reforms in emerging economies: a socio-material perspective. Public Money & Management, 43(7), 762–768.

- Sciulli, N., & Sims, R. (2007). Public sector accounting education in Australian universities: An exploratory study. Sunway Academic Journal, 4, 44–58.

- Sydow, J., & Schreyögg, G. (2013). (Eds). Self-reinforcing processes in and among organizations. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Sydow, J., Schreyögg, G., & Koch, J. (2009). Organizational path dependence: Opening the black box’. Academy of Management Review, 34(4), 689–709.

- Talbot, C., & Talbot, C. (2015). Bridging the academic–policy-making gap: practice and policy issues. Public Money & Management, 35(3), 187–194.

- Ter Bogt, H., & van Helden, J. (2012). The practical relevance of management accounting research and the role of qualitative methods therein: The debate continues. Qualitative Research in Accounting & Management, 9(3), 265–273.

- Tucker, B., Ferry, L., Steccolini, I., & Saliterer, I. (2020). Debate: The practical relevance of public sector accounting research; time to take a stand—A response to van Helden. Public Money & Management, 40(1), 5–7.

- Tucker, B., & Lowe, A. D. (2014). Practitioners are from Mars; academics are from Venus? An investigation of the research–practice gap in management accounting. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 27(3), 394–425.

- Tucker, B., & Schaltegger, S. (2016). Comparing the research–practice gap in management accounting: A view from professional accounting bodies in Australia and Germany. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 29(3), 362–400.

- Van Helden, J. (2019). New development: The practical relevance of public sector accounting research: Time to take a stand. Public Money & Management, 39(8), 595–598.

- Van Helden, J., Aardema, H., ter Bogt, H., & Groot, T. (2010). Knowledge creation for practice in public sector management accounting by consultants and academics: Preliminary findings and directions for future research. Management Accounting Research, 21(2), 83–94.

- Van Helden, J., & Argento, D. (2020). New Development: Our hate–love relationship with publication metrics. Public Money & Management, 40(2), 174–177.

- Wilkinson, B. R., & Durden, C. H. (2015). Inducing structural change in academic accounting research. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 26, 23-36.