IMPACT

This article explores how local governments adapt their financial management systems during the chaos and uncertainty of war; the authors use the recent military conflict in Ukraine as a case study. This article has lessons for public managers and policy-makers—especially at the local government level. The authors emphasise the importance of aligning state and local financial systems, and the need for flexibility in financial decision-making during periods of high uncertainty. The article also highlights the uneven effects of wars in different local areas, urging policy-makers to ensure that top-level strategies accurately reflect local realities. The insights from this article deepen our understanding of how we should approach disaster recovery, contributing to more effective and resilient responses to future crises.

ABSTRACT

As a human-made disaster, war causes unprecedented stress and high uncertainty at the local government level. Local authorities need to normalize financial management, given real-time damages and losses, while maintaining delivery of critical public services. As well, they need to forecast and plan for future needs. The research literature on financial management and accounting during disasters is rich in terms of cases of natural and human-made disasters affecting or addressed by accounting practices; however, with the exception of a few studies, the nuances of local financial management during wars have been overlooked. Using complexity theory, the authors explore local financial management as a complex adaptive system and how it develops under an armed conflict.

It is not enough to win a war; it is more important to organize the peace (Aristotle).

Complexity theory focuses on storylines through time, different from place to place and evolving (Teisman & Klijn, Citation2008, p. 288).

Introduction

Wars cause significant economic and societal problems (Harrison, Citation2022; Akbulut-Yuksel, Citation2022). When wars last, their devastating consequences accumulate, resulting in a serious lack of resources which further impacts multiple spheres of human lives. After infrastructure is destroyed, collective action is needed to ensure the continuity of societal systems. It is impossible to detach damages and losses from reconstruction and recovery. The complexity of the recovery process is determined by its multifaceted and intricate character—it is not just about the restoration of physical damage but also requires re-establishment of socio-economic and institutional stability to enable a return to a peaceful life (Barakat, Citation2005).

The research literature on financial management and accounting during disasters is rich in terms of cases of natural and human-made disasters affecting or addressed by accounting practices (Chwastiak, Citation2001; Chwastiak, Citation2006; Chwastiak & Lehman, Citation2008; Matilal & Hopfl, Citation2009; Cho, Citation2009; Sargiacomo, Citation2015; Sargiacomo & Walker, Citation2022; Cifuentes-Faura, Citation2023a, Citationb). However, with the exception of a few studies (for example Ilievski & Taleski, Citation2009; Abazi, Citation2004; Serwer, Citation2019), the nuances of local financial management during wars have been overlooked. Local governments (LGs) are the first to face a human-made disaster and its effects, for example ruined infrastructure, increased needs for defence, humanitarian support, and healthcare services. One of the major challenges to be handled locally is addressing constantly emerging, and sometimes contradictory, needs with limited institutional capacity and fragile social, economic and security conditions (Makdisi & Soto, Citation2023). Given the critical role that LGs play in providing essential services to their populations and maintaining social infrastructure, it is crucial to fill this gap in the literature. Therefore this article explores how LGs normalize and re-plan a complex financial management system given uncertainty caused by a war.

The article is contextualized around the warfare that started on 24 February 2022 after Russia invaded Ukraine. The Russian invasion caused the biggest military conflict in Europe since the Second World War, triggering deep humanitarian, economic, social and geopolitical crises (Grossi & Vakulenko, Citation2022) which have spread beyond the European continent. The war had (and continues to have) a negative impact on Ukraine. It has led to a reduction in the country’s economic potential, causing a decrease in production and exports, deterioration of investments, devaluation of the national currency, and inflation (National Bank of Ukraine, Citation2023). In addition to the urgent need to fund large-scale military operations on a daily basis, enormous resources are necessary to keep the Ukrainian economy functioning (IMF, Citation2022).

Since the first days of the war, Ukrainian LGs were thrown into a complex and dynamic environment, in which they had to adapt to new realities and balance competing needs and priorities. To explore this struggle, we mobilize complexity theory which has not been widely used to date used in the accounting and public administration literature (Teisman & Klijn, Citation2008). Complexity theory explains how organizations self-organize, adapt to their environments and cope with uncertainty (MacIntosh et al., Citation2006; Mitleton-Kelly, Citation2003; Stacey, Citation1995). This theoretical lens may offer alternative insights on how LGs during a wartime normalize and re-plan complex financial management systems in highly stressful conditions responding to changing circumstances and demands.

The remainder of this article is structured as follows. The next section provides a literature review on local financial management practices challenged by disasters; next, our theorical framework is introduced to explain how local financial management, as a complex system, reacts to a human-made disaster. A methods section follows. Our findings illustrate how Ukrainian LGs changed their financial management systems during the first year of the full-scale war. In our discussion, we show how LGs self-organized to navigate between immediate and long-term needs in highly uncertain and complex context. The article closes with conclusions, practical implications, limitations and suggestions for future research.

Literature review

Local financial management in course and aftermath of a human-made disaster

Essentially ‘local financial management’ refers to processes and strategies that LGs use to manage local financial resources. The two key elements of local financial management systems are resources and actors.

LGs rely on stable revenue planning to ensure sufficient funds to cover local needs (Menifield, Citation2017). Local financial management connects generating revenues by raising funds from various sources (for example property taxes, fees and charges, grants and inter-governmental transfers), spending funds to provide services to local population (Jones & Pendlebury, Citation2010) and balancing the two. In this way, under normal conditions, local financial management ensures the stability and sustainability of a local community.

A disaster is an event that critically disturbs the functioning of a society (United Nations, Citation2009). Typically, disasters are divided into two broad groups—depending on whether they have been caused by nature or humans. On one hand, natural disasters (like earthquakes) affect different territories, organizations and societies, often resulting in multiple deaths, economic collapse and a humanitarian emergency (for example Sargiacomo, Citation2015; Sargiacomo & Walker, Citation2022). On the other hand, armed conflicts and wars are human-made disasters and lead to loss of life, human displacement (Zibulewsky, Citation2001) and many other subsequent crises.

Considering the effects on security, economy, social and democratic institutions that states at war face during human-made disasters, the impact on local financial management has, surprisingly, rarely been studied. There are some publications on local finances in the context of armed conflicts in the Balkans in 1990s (Woodward, Citation1995; Ilievski & Taleski, Citation2009; Serwer, Citation2019). The destruction of infrastructure, human displacement and economic disruption impaired the collection of local revenues, the management of expenditures, and the maintenance of financial stability. Balkan LGs responded by reframing their financial practices, for example by establishing emergency funds to support social welfare programmes and repair their infrastructure. In Bosnia and Herzegovina, for example, a reconstruction and development fund was created with the support of international aid to facilitate recovery projects. In Kosovo, a United Nations mission played a significant role in updating the system of tax management and financial reporting, which improved local accountability and strengthened public trust in local financial system. International donors supported the Balkan states by providing technical assistance and financial support and facilitated LGs with establishing emergency funds, restoring financial systems, and strengthening their financial management capacity (Abazi, Citation2023; Citation2004). While, in some cases, the support of international institutions can have positive results in emergency normalization of financial management systems, they have been known to fail because they have been unable to address the highly turbulent local habitat (Vakulenko, Citation2021).

To date, the majority of the academic publications on wartime local financial management have highlighted the value of international funding, the establishment of security measures and political disclosures. Most studies considered complex socio-economic matters only tangentially or superficially, despite the multiple effects of wars (Del Castillo, Citation2008). As military conflicts differ in duration and intensity, their devastating consequences touch human, social, economic and natural spheres of local communities causing interwoven sets of challenges (see World Bank, Citation1998; Kreimer et al., Citation1998; World Bank, Citation2022; Cifuentes-Faura, Citation2023a), for example:

Decline in human development and security indicators, for example life expectancy, infant mortality, and access to healthcare and education.

Destruction of civil infrastructure. for example transport, communications, water, energy and housing.

Displacement of the population causing humanitarian risks and brain drain (emigration of skilled workers).

Increase in demand for social assistance by vulnerable groups.

A drop in economic potential and increased public debts.

Withdrawal of foreign investments.

International and local trade disruption.

Environmental damage, including irreparable losses within ecosystems.

Ensuring transparency and accountability in government performance.

While there is no perfect recipe for managing local finances during wartime, there is international experience of possible transformation of fiscal policies, reporting, debt and tax management to address local challenges during the war. However, there is still a lack of nuanced understanding about the way local financial management is normalized and re-planned during a war, which we address in this article using complexity theory.

Complexity theory

Complexity theory examines how phenomena develop under different influences and how the non-linearity of this development can be explained (Turner & Baker, Citation2019). The main theoretical assumption rejects that a world consists of defined linearly-connected elements, and complexity theory takes a more dynamic approach than several traditional theoretical streams follow (Teisman & Klijn, Citation2008). However, ‘like many other scientific theories, the complexity theory is not a unified and homogeneous perspective’ (Teisman & Klijn, Citation2008, p. 288). Deriving from natural sciences and biology (Schneider & Somers, Citation2006), the universal assumptions of this theory have influenced other sciences like organization theory and management (Stacey, Citation1995; Maguire & McKelvey, Citation1999), economics (Arthur, Citation1999), neuroscience (Sporns, Citation2016), and ecology (Levin, Citation1998). Despite its interdisciplinary application, the main intention of complexity theory is to study system change and system dynamics as result of complex interactions (MacIntosh et al., Citation2006; Klijn, Citation2008). This theoretical lens can explain how organizations become resilient, adapt and innovate (Uhl-Bien et al., Citation2007).

Complexity theory is built around two key phenomena: complex systems and their behavioural patterns. Complex systems contain ‘numerous interacting identities (parts), each of which is behaving in its local context according to some rule(s), law(s) or force(s)’ (Maguire & McKelvey, Citation1999, p. 26). Social systems, inhabited by ‘self-reflecting agents who try to understand the social systems they themselves are in (the double hermeneutics problem)’ (Giddens, Citation1984; in Teisman & Klijn, Citation2008, p. 290) are one of distinctive examples of such a complex system. The individual parts of social systems respond to contextual influences and produce patterns (Klijn, Citation2008). The emergence means that complex forms merge from microscale interactions. In this way, behaviour of relatively autonomous individual agents boosts emergence, which further results in complex dynamic developments of a social system.

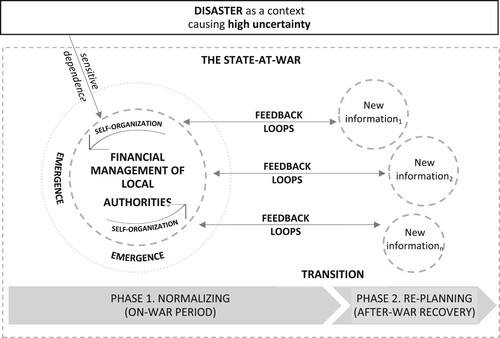

From a complexity theory perspective, systems are characterized by self-organization, emergence, sensitive dependence on contextual conditions, feedback loops and phase transitions (Mitchell, Citation2009). illustrates these in the context of local financial management during a human-made disaster.

Figure 1. Local financial management during a human-made disaster from complexity theory perspective.

Self-organization represents the system’s capacity to spontaneously arrange its components into an organized pattern without external control (Camazine et al., Citation2001). The economic system may reorganize itself in response to a massive disruption like a war (Camazine et al., Citation2001). In such situations, ‘actors are self-organizing, creating their own perception of what they want and how to behave in the landscape they are in’ (Teisman & Klijn, Citation2008, p. 289): for example, as observed in autopoietic systems (Luhmann, Citation1986), self-referential or dissipative or adaptive behavioural patterns (Teisman & Klijn, Citation2008).

Emergence relates to appearance of complex patterns arising from simpler components. This means that minor changes in the initial state of a system may result in considerably different outcomes (Lorenz, Citation1993): the so-called a ‘butterfly effect’. In particular, actions of multiple actors from different sectors combine in a way that to produce effects that cannot be traced to the behaviour of the individual agents alone (Klijn, Citation2008, p. 302).

Sensitive dependence on contextual conditions depicts a situation when an event can cause unpredictable effects due to sensitivity to initial conditions (Lorenz, Citation1993). As ‘seemingly stable equilibriums can be suddenly disrupted by unexpected events’ (Klijn, Citation2008, p. 302), actors need to adjust their behaviour to fit a new context.

Feedback loops refer to a system’s cycles of information or causality, for example feedback on market condition, new policies, or the progress of a war (Sterman, Citation2000). These feedback loops can lead to unintended consequences, which requires actors to adapt as needed.

Phase transitions are changes in systems’ behaviour due to a shift in external conditions (Kauffman, Citation1993). This may include rapid changes and reconfigurations in response to a warfare escalation or de-escalation (Kauffman, Citation1993).

In summary, from a complexity theory perspective, wartime local finances are challenged by unpredictable dynamics requiring actors to self-organize considering feedback from new inputs of information and, thereafter, emergent properties. This perspective provides a new insight on how LGs embrace complexity and uncertainty by adjusting local finances to navigate immediate and long-term effects of a wartime.

Methodology

Cases

A qualitative case study (Yin, Citation2018) is one of the most commonly used strategies in management research (Priya, Citation2021). A case study explores a phenomenon bound by time and actions (Creswell, Citation2014), which means that the analysis is conducted within its natural setting, i.e. in a real-life context (Yin, Citation2018). Case study research is the best way to investigate ‘complex and dynamic phenomena where many variables are involved’, where there are observed ‘actual practices, including the detail of significant activities that may be ordinary, unusual or infrequent’, and where there are present ‘phenomena in which the context is crucial because the context affects the phenomena being studied’ (Cooper & Morgan, Citation2008, p. 160). Accordingly, given the research aim of our article, a qualitative case study method seemed to be the best methodological tool to explore local financial management of war-affected Ukrainian LGs. In this way, our research methodology complements and extends recent literature on the war that mostly applies quantitative methods with a focus on corruption, transparency and accountability (Cifuentes-Faura, Citation2023a, Citationb).

Representing the lowest level of self-government, our selected LGs present several different scenarios in terms of their locations in different regions, their size and the effects that the war has had on them (see ). The motivation for choosing our case study LGs was:

They enabled us to analyse different behavioural patterns of LGs during the war, thus providing a richer insight into local financial management system as a phenomenon.

In each LG co-authors had acquaintances which allowed a ‘snowball effect’ in terms of reaching more relevant informants.

Table 1. Characteristics of the case study Ukrainian LGs.

Data collection and analysis

The timeframe for our study was February 2022 to February 2023. Data collection was performed between November 2022 and June 2023 in three stages:

Four background interviews with representatives of Ukrainian NGOs and university scholars with expertise in local governance. These interviews enabled us to understand the wartime challenges faced by Ukrainian local authorities and served as a foundation for further stages.

Analysis of secondary data (see ) including the Ukrainian central government legislature and reports of several international donor agencies. This analysis allowed us to build a solid contextual knowledge about the impact of the war and to narrow our focus to local financial management.

Data collection from LGs: this included interviews with representatives from local administrations and/or councils with experience in financial management, accounting, and budgeting (see ). The consent of informants to participate in the research was obtained upon the condition of anonymity.

Table 2. Secondary sources analysed for contextualization.

Table 3. Information about interviewees.

Primary data was triangulated with local documentation, i.e. city council reports, local budgets, financial statements and policy documents, and the information gathered during the first two stages.

Based on abductive reasoning (Mantere & Ketokivi, Citation2013), the collected data was reviewed and structured in line with a pre-defined theoretical approach after each stage. Main concepts of complexity theory, i.e. self-organization, emergence, sensitive dependence, feedback loops, and phase transitions, served as thematic strings for the analysis. The richest dataset obtained during the third stage was analysed tracing LGs behavioural patterns in normalizing and re-planning financial management during the wartime in Ukraine.

Credibility and reliability

The credibility and reliability of qualitative case studies is important, since ‘without rigor, research is worthless, becomes fiction, and loses its utility’ (Morse et al., Citation2002, p. 14). To ensure credibility, i.e. that the findings are congruent with the real world (Merriam, Citation1998), we triangulated our data sources. In particular, interviews were conducted with divergent groups of actors engaged in local financial management in Ukraine and coupled with an analysis of secondary data. Together these multiple sources of data provided a rich and accurate overview of the changes in LG financial management.

Reliability is ensured by demonstrating that the findings are consistent and can be repeated (Yin, Citation2018). For this study, we followed objective criteria for selecting cases, used an interview guide and followed data analysis stages based on complexity theory. This was done to ensure that the research process was both rigorous and comprehensive.

Empirical findings

The war and intrinsic nature of Ukrainian local finances

To explore local financial management systems, we needed, first, to define the composition of financial resources; and, second, to discover the local financial management processes, i.e. local actors’ decision-making on collecting and allocating resources. As the war is a critical contextual factor, the following is a snapshot of Ukrainian legislative framework is presented that regulates local financial management before 24 February 2022 and the changes that occurred up to 24 February 2023.

In Ukraine, local revenues are divided into money collected by LGs (‘own’) and ‘transferred’ by the state: also called ‘inter-budgetary transfers’.

When it comes to local expenditures, according to the Budget Code of Ukraine (2010), several classifications exist:

Functional: depending on executed expenditure-related functions.

Economic: based on the economic characteristics of operations during which expenses incurred, i.e. current, capital and borrowing and repayments.

Departmental: varies between administrative unit using funds.

Programme: depending on budgetary programmes.

Local revenues and expenditures are divided into general and special funds depending on how they are planned and distributed. The general fund is used for LGs’ basic functions (salaries, energy carriers, medicines, housing and communal management and others). When local resources are insufficient to cover these expenses, extra-budgetary transfers are applied. The special fund is used to finance specific needs (for example development expenses including work on repairs, reconstruction and restoration). Additionally, an LG can set up a reserve fund to be used for emergencies or other urgent, unexpected problems.

The introduction of martial law in Ukraine affected both the structure of local financial sources and the way local finances could be managed during the war. A detailed overview of key legislative acts adopted by the Ukrainian central government from February 2022 to February 2023 is available from the authors upon request.

During the early part of the war, the main legislative changes were oriented towards strengthening national security, easing taxation for private entities, reducing excise duties and regulating for the use of charitable transfers and donations. The classification of local expenditures was expanded to include expenditures related to providing support and assistance to internally displaced and/or evacuated persons due to the war. In addition, a change was made to provide a sequence of local expenditures under martial law.

The primary/prioritized expenditures are:

Expenses of administrators (recipients) of budget funds performing tasks related to the introduction and implementation of measures of the legal regime of martial law.

Repayment of local debt.

Local debt servicing costs.

Fulfilment of warranty obligations.

Expenditures on salaries of public employees, social security, purchase of medicines, drinking water supply, provision of food, communal services, heating, and services for people with disabilities.

Payment of social services, purchase of stationery, communication services, payment of Internet providers, purchase of notification and public information systems, funeral services, payment for maintenance of burial places, improvement of settlements.

Payment for services for maintenance and repair of road transport, purchase of materials for urban electric transport, insurance, cleaning of sewage systems, maintenance of electrical networks, laundry services, operational maintenance of roads.

A summary of pre-war local revenues and expenditures vis-à-vis the introduced legislative changes is outlined in .

Table 4. Changing structure of local revenues and expenditures in Ukraine before and during the war.

presents a technical overview of local financial management in Ukraine before the war and the changes after one year under martial law, but the picture it resents is rather static. Several legal acts allowed more flexibility for LGs in using their resources, while the destructive context of the war created high uncertainty for LGs. As we were interested in ‘making films of how phenomena develop under a variety of influences’ (Teisman & Klijn, Citation2008, p. 288), we needed to look at how different LGs normalized and re-planned their financial management systems.

Phase 1: Normalizing

Ukraine has been exposed to Russian aggression since 2014, when the eastern Ukrainian territories were occupied, and the Crimean Peninsula was annexed. The full-scale war began on 24 February 2022 threatening the whole country and caused extraordinary challenges for Ukrainian society. The first couple of days were marked with military actions of high intensity, as Russian troops crossed several Ukrainian borders. Additionally, rocket attacks around the country destroyed production facilities, transport hubs, critical infrastructure, and civil utilities. This affected the system of local financial management, which had to be regulated manually to ensure quick response to challenges and normalization (in the short term) of the local financial management system.

An overall shrinkage in local revenues, which is the major resource for municipal funding (IMF, Citation2022), was observed in all Ukrainian LGs, yet the situation was exceptionally stressful for the LGs under Russian occupation (LG A) or those situated close to the zone of active military action (LG B).

A decrease in their own revenues in LGs A and B related to pausing the activities of local public institutions and businesses. Several public institutions in the spheres of education (schools and universities), culture, sports, and community services stopped functioning in the first months of the war. This happened due to the destruction of premises and the impossibility of work caused by the danger of hostilities:

Occupation was a nightmare … Around 60 civilians lost their lives when trying to evacuate. The [occupying soldiers] damaged more than 300 residential buildings, leaving hundreds of families homeless. They ruined our infrastructure. A medical clinic, a school, a water tower, and a water purification station were destroyed. This impacted the life of our community and, of course, affected our financial management system. (Interviewee 3.1, LG A.)

For all LGs, tax revenues decreased, as central authorities granted exemptions for certain categories of taxpayers for paying single and environmental taxes, property tax, tax on immovable property other than land and reducing excise tax on fuel imports. While main sources of revenue remained pretty much the same for LGs, the main change concerned the volume of collected financial sources:

Despite being occupied, the main source of our local revenues was tax revenues, with personal income tax reaching 65.72% and the single tax [enterprise income tax]: 10.29%. However, the volume [of our income] was reduced due to the outflow of population and destruction of some enterprises that were the main taxpayers of the pre-war period. (Interviewee 3.2, LG A.)

As the war started, we changed our approach to local financial management. From strategic, it became operational. At the beginning, generation of revenues was not [our] main concern; we were worried about how to allocate resources as much as needed as quickly as possible to as many people as possible. The first days and weeks we were addressing needs of citizens urgently and much was done voluntarily. (Interviewee 3.12.)

We are located close to the active military zone. So, for us, especially during the first months, there was high uncertainty on the volume of collected revenues, so we decided to suspend expenses. We reduced [the] salaries of officials who were away; we also reduced expenditures on land management. Since capital expenditures were prohibited by the central government, we did not use funds for capital restoration. We wanted to use funds effectively [and] to save in case the money does not come to the budget at all [i.e. shortfalls in the budget]. (Interviewee 3.6, LG B.)

To stabilize the life of our community and the functioning of its critical infrastructure, we redistributed funds for the implementation of anti-crisis measures. Our priority was expenditures for the support of local defence units, social support for internally displaced persons and local residents. We additionally funded measures to prevent the consequences of emergency situations, for example arranging shelters, purchase of generators, and others. (Interviewee 3.14, LG D.)

Phase 2: Re-planning

The phase that was directed towards re-planning emerged around June–July 2022. It did not replace the normalizing phase but, rather, layered over it. LGs did not only have to be ready to adjust their local financial management systems to possible emergencies, but also they needed to start thinking strategically about how to combine scarce resources in planning reconstruction and recovery.

With many LGs facing a lack of funds in the general fund to cover all emerging needs, the central government allowed LGs to transfer resources from special to general funds to spend on urgent needs:

LGs in Ukraine have different needs, as some are recovering after occupation, others are in the war zone, and others are providing the rear. Therefore, allowing them to transfer funds from the special fund to the general fund helps finance their needs more effectively. (Interviewee 1.3.)

Local financial resources are never sufficient to ensure the full implementation of all powers. The more financial resources we have, the more opportunities to use them for development and meeting the needs of citizens. We directed most of the funds to the social sphere—education, social protection, and healthcare. In 2022, the educational subvention [was] reduced, so we plan to compensate [for this] from the local budget. Luckily, we have not experienced significant war-related destructions, but we are carrying out ongoing road repairs and infrastructure development. This will improve the conditions for the [military] brigades stationed here and create favourable conditions for new businesses. As for the remaining funds, we directed almost all of them to help the Armed Forces. (Interviewee 3.9, LG C.)

In July 2022, the Ukrainian government developed a recovery plan for Ukraine. The growing restoration needs and constantly changing scale and character of losses made the recovery plan rather ambiguous but, nevertheless, it served as a roadmap for LGs’ planning. The central government introduced an additional subsidy from 2023 for the implementation of the powers of local self-government bodies in de-occupied, temporarily occupied and other territories of Ukraine that had been negatively affected by the war. In addition, a fund for the mitigation of the consequences of armed aggression was added to the state budget for the restoration of destroyed infrastructure:

The funding provided by the state is for the restoration of critical infrastructure facilities, houses and other priority measures. The country-wide destructions are extensive; thus, the funds are not enough [to] help all LGs in planning their recovery. In addition to a destroyed school to be restored, we need to address the ecological consequences of the war [and] organize de-mining of the territory; this requires huge additional funds. Therefore, we are actively reaching out to [the] international community to establish direct contact and co-operate to ensure recovery. (Interviewee 3.1, LG A.)

While still facing high uncertainty due to rather active military actions, we need to plan our future. We combine emergency response and plans for sustainable development. Therefore, we plan expenses for the restoration of infrastructure and increase revenues to local budgets. Already now, we see that the government is making changes to the priority of spending by responding to new challenges faced locally. We search for available financial resources, these can be national programmes to support LGs, the fund for mitigation of the consequences of armed aggression, as well as grants and soft loans from international partners. (Interviewee 3.7, LG B.)

From October [2023], we [will] lose a major source of our revenue—personal income tax of military officers … the redistribution of personal income tax from local to the state budget. Given this, we [will] gradually re-plan our revenues by focusing on land tax. We will work on developing our agricultural potential to attract more businesses to use our lands. (Interviewee 3.10, LG C.)

Discussion

‘The seemingly stable equilibrium’ of Ukraine has been ‘suddenly disrupted by the unexpected event’ (Klijn, Citation2008, p. 302) represented by the Russian invasion. Accordingly, the war caused uncertainty and complexity due to its unpredictable character, which paved the way for the so-called ‘non-linear dynamics’ of the financial management system (Teisman & Klijn, Citation2008). This article has connected the immediate and prospective timeframes of financial management through a complexity theory lens—demonstrating the highly dynamic nonlinear nature of local financial management systems in war scenarios.

When trying to navigate between instant and long-term perspectives, in an uncertain and complex landscape, Ukrainian LGs demonstrated a high level of self-organizing capacities, acting ‘as interdependent parts of a complex whole’ (Eppel, Citation2017, p. 853). LGs did not simply follow established laws and principles (Teisman & Klijn, Citation2008, p. 288), but they organized the elements of their own system (local financial resources), which were further integrated into a larger compounded whole (i.e. local financial management in a specific LG).

The complexity perspective presented local financial management as being composed of many interconnected parts (including resources and actors) that interact with each other. The system’s behaviour, as a whole, cannot always be predicted by looking at its separate parts. In their search for survival, ‘agents’ respond to external pressures from constantly changing ‘landscape’ (Teisman & Klijn, Citation2008, p. 289). explains the nonlinear dynamics of Ukrainian wartime local financial management based on the view provided by complexity theory.

Table 5. The non-linear dynamics of wartime local financial management in Ukraine as a complex system.

The dynamics of LG financial management can be visualized in two phases that, in time, are repeated to achieve new ‘punctuated equilibrium’ (ibid., p. 292).

The war has transited through different phases requiring behavioural changes of complex systems. The critical changing point was in July 2022. This appeared when LGs normalized their local financial management systems (during the first months of the war), the subsequent re-planning phase layered over the normalization requiring LGs to balance between urgent and long-term needs. According to one our interviewee 3.7, this transition required a constant revision of local priorities and allocation of sufficient resources to meet completed needs. Moreover, a need for additional funding emerged to reconstruct a post-war city (for example road repairs and infrastructure development: interviewee 3.9) thus triggering (again) a new transition phase in the budgeting process.

The changing dynamics of the war also resulted in policy updates from the central government (see ). Changes in the legislative framework created ‘feedback loops’ (i.e. new pieces of information) affecting local financial management (Sterman, Citation2000) that either amplified or reduced the effects of those changes and these sometimes created unintended consequences. For example, in LG B (according to interviewee 3.6), the funding for land management measures was reduced which led to a decline in the quality of land management, which, in turn, further decreased the LG’s income.

At the same time, all LGs demonstrated self-organization capabilities. They adapted and reorganized their local financial management systems in response to changes in their respective landscapes. As being those most affected by the war, LGs A and B simplified and optimized their management structures to increase efficiency and effectiveness of use of local resources on the normalizing phase. In the re-planning phase, LGs started seeking new funding sources and adjusted their expenditures (see Interviewee 3.7) in response to changing circumstances. During the war, LGs interacted with different actors, thus displaying emergent properties (Klijn, Citation2008, p. 302) by adjusting their finances to address emerging local needs. In particular, from the analysis of investigated case studies we fund solutions like multi-actor engagement into local reconstruction, defence, humanitarian aid and others.

The behavioural patterns that emerged from the interactions taking place in these complex financial management systems are synthetized as follows. During the normalization phase, LGs were trying to adjust their financial management system to meet urgent needs arising from the war. These included many simultaneous events (increasing security measures, placement of people, relocation of business and damages of infrastructure) that had to be addressed that the raise of complexity. While focusing on short-term measures, LGs initiated developing long-term plans for the local recovery. When LGs normalized the system, they started re-planning but in highly uncertain conditions. The use of complexity theory enabled tracing LGs’ engagement into interactions with multiple actors seeking for additional sources of income, at the same time being ready to address new damages as the war continued. By so doing, the emerging ‘non-linear dynamics’ of local financial managements systems, although proceeding through different variations, will necessarily pass through different states of ‘punctuated equilibrium’, ‘normalizing’ and ‘re-planning’ phases, as long as the war lasts.

Conclusion

The ongoing military conflict between Ukraine and Russia has significantly impacted Ukraine’s economy, causing a reduction in economic potential, production and exports, as well as a deterioration of the investment climate, a fall in the value of the national currency, and inflation.

We used complexity theory for our analyses—the theory suggests that solutions to complex problems are often found through experimentation and learning rather than through top-down planning and control (Holland, Citation1996). LGs in Ukraine demonstrated that they have been adopting a flexible approach to their financial management in a way that was appropriate to their local needs. Despite the challenges that LGs faced in managing their finances during the war (i.e. reduced revenues from local taxes, increased expenditures on security and humanitarian needs, the need to rebuild physical infrastructure and the need to restore human capital), LGs self-organized in normalizing and re-planning their financial management systems by navigating through several revenue sources and changing the structure of their expenditures.

The limitation of our study relates to our relatively few case studies. Although a qualitative case study is considered to be an adequate tool to investigate complex and dynamic phenomena (Cooper & Morgan, Citation2008, p. 160), we acknowledge that we used primary sources drawn from a limited number of selected LG cases. The alternative methodological approach that could yield wider results on the financial condition of LGs is a quantitative analysis of a selected array of financial indicators. It could also be applied to a wider sample of LGs. This could be a starting point for future studies on local financial management during a human-made disaster. Other research directions might include a nuanced analysis of public–private partnerships, hybrid organizations, international humanitarian organizations and financial donors in supporting LGs affected by the war. Specifically, how various types of assistance, such as technical support, financial aid, and capacity-building initiatives are combined. Additionally, exploring the role of the state in managing the intricate and complex recovery process could shed light on challenges and opportunities of co-ordinating across different governmental levels, as well as connecting political and economic in addressing the challenges LGs face during a human-made disaster.

Moving forward

The practical implications of our findings relate to the importance of state and local financial systems being aligned. During high uncertainty, LGs might require more flexibility in financial decision-making to ensure timely and accurate responses, yet they also rely on state guarantees on ‘protected’ expenditures to gain stability and to normalize their local financial system. Wars cause uneven effects in different areas; therefore policy-makers need to ensure that strategies designed at the top level accurately reflect local realities.

We hope that this article will convince the accounting and public management research community to devote much more attention to effective public financial management during and after human-made disasters.

Acknowledgment

The authors extend their sincere gratitude to the editorial team for their excellent follow-up and to the two anonymous reviewers for their invaluable comments, which greatly contributed to the improvement of this paper. This article is part of the Quality of Accounting and Auditing in the Public Sector (QAAPS) project at Nord University Business School, funded by the Norwegian Research Council (project number 314460). We are deeply thankful for the support received throughout the process of writing and publishing this research on Ukraine.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Veronika Vakulenko

Veronika Vakulenko is an Associate Professor at Nord University Business School, Norway. Her research directions cover, but are not limited to, public sector management, in particular public accounting, budgeting, finance, and auditing; social accountability; emergency governance and organizational changes. In her research Veronika applies behavioural and institutional theoretical approaches, and conducts interdisciplinary studies. The context of research is developing countries, emerging economies, or those in transition, and specifically Ukraine.

Massimo Sargiacomo

Massimo Sargiacomo is a Professor at D’Annunzio University of Chieti-Pescara, Italy. Massimo is President of the Italian Society of Accounting History, and prior President of the Academy of Accounting Historians. His current research is focused on accounting and management practices in the aftermath of disasters, accounting and corruption/fraud in the public sector, immigration management, accounting and calculative practices for mega-projects, research assessment and university performance management systems.

Veronika Klymenko

Veronika Klymenko holds a master’s in public sector economy from Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv, Ukraine and Nord University, Norway (2023). Veronika specializes in financial management, particularly for local authorities in Ukraine, during and after conflicts, assessment of financial health of local governments and long-term management for post-war recovery.

References

- Abazi, E. (2004). The role of the international community in conflict situations.: Which way forwards? The case of the Kosovo/a conflict. Balkanologie: Revue d’études pluridisciplinaires, 8(1), 9–31.

- Abazi, E. (2023). Kosovo’s foreign policy and bilateral relations. Routledge.

- Addison, T., Billon, P. L., & Murshed, S. M. (2001). Finance in conflict and reconstruction. Journal of International Development, 13(7), 951–964.

- Akbulut-Yuksel, M. (2022). Unaccounted long-term health cost of wars on wartime children. https://cepr.org/voxeu/columns/unaccounted-long-term-health-cost-wars-wartime-children.

- Arthur, W. B. (1999). Complexity and the economy. Science, 284(5411), 107–109.

- Barakat, S. (2005). After the conflict: Reconstruction and development in the aftermath of war. I.B. Tauris.

- Bertaux, D., & Kohli, M. (1984). The life story approach: A continental view. Annual Review of Sociology, 10(1), 215–237.

- Bird, N., & Amaglobeli, D. (2022). Policies to address the refugee crisis in Europe related to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. IMF Notes No 2022/003.

- Bourdieu, P., & Balazs, G. (1999). The weight of the world: social suffering in contemporary society. Stanford University Press.

- Camazine, S., Deneubourg, J.-L., Franks, N. R., Sneyd, J., Theraula, G., & Bonabeau, E. (2001). Self-organization in biological systems. Princeton University Press.

- Cho, C. (2009). Legitimation strategies used in response to environmental disaster: A French case study of Total SA’s Erika and AZF incidents. European Accounting Review, 18(1), 33–62.

- Chwastiak, M. (2001). Taming the untamable: planning, programming and budgeting and the normalization of war. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 26(6), 501–519.

- Chwastiak, M. (2006). Rationality, performance measures and representations of reality: planning, programming and budgeting and the Vietnam war. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 17(1), 29–55.

- Chwastiak, M., & Lehman, G. (2008). Accounting for war. Accounting Forum, 32(4), 313–326.

- Cifuentes-Faura, J. (2023a). The role of accountability and transparency in government during disasters: the case of Ukraine–Russia war. Public Money & Management, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540962.2023.2243131.

- Cifuentes-Faura, J. (2023b). Government transparency and corruption in a turbulent setting: The case of foreign aid to Ukraine. Governance, 37(2).

- Cooper, D. J., & Morgan, W. (2008). Case study research in accounting. Accounting Horizons, 22(2), 159–178.

- Creswell, J. W. (2014). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed method approaches (4th edn.). Sage.

- Del Castillo, G. (2008). Rebuilding war-torn states: The challenge of post-conflict economic reconstruction. Oxford University Press.

- Eppel, E. (2017). Complexity thinking in public administration’s theories-in-use. Public Management Review, 19(6), 845–861.

- Giddens, A. (1984). The constitution of society: outline of the theory of structuration. MacMillan.

- Grossi, G., & Vakulenko, V. (2022). New development: Accounting for human-made disasters—comparative analysis of the support to Ukraine in times of war. Public Money & Management, 42(6), 467–471.

- Gubrium, J. F., & Holstein, J. A. (eds.). (2002). Handbook of interview research: Context and method. Sage.

- Harrison, M. (2022). Economic warfare and Mançur Olson: Insights for great power conflict. https://cepr.org/voxeu/columns/economic-warfare-and-mancur-olson-insights-great-power-conflict.

- Holland, J. H. (1996). Hidden order: How adaptation builds complexity. Basic Books.

- Humphreys, M. (2003). Economics and violent conflict. Harvard School of Public Health.

- Ilievski, Z., & Taleski, D. (2009). Was the EU's role in conflict management in Macedonia a success? Ethnopolitics, 8(3-4), 355–367.

- IMF. (2022). Press release. https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/CR/Issues/2022/12/21/Ukraine-Program-Monitoring-with-Board-Involvement-Press-Release-Staff-Report-and-Statement-527288.

- IMF. (2023). UKRAINE: staff report for the 2023 article IV consultation, second review under the extended arrangement under the extended fund facility, and requests for modification of performance criteria and a waiver of nonobservance of performance criterion. Country Report No. 2023/399.

- Jones, R., & Pendlebury, M. (2010). Public sector accounting (6th edn). Financial Times/Prentice Hall.

- Kauffman, S. A. (1993). The origins of order: Self-organization and selection in evolution. Oxford University Press.

- Klijn, E. H. (2008). Complexity theory and public administration: What's new? Key concepts in complexity theory compared to their counterparts in public administration research. Public Management Review, 10(3), 299–317.

- Kreimer, A., Eriksson, J., Muscat, R., Arnold, M., & Scott, C. (1998). The World Bank’s experience with post-conflict reconstruction. World Bank Group.

- Levin, S. A. (1998). Ecosystems and the biosphere as complex adaptive systems. Ecosystems, 1(5), 431–436.

- Lorenz, E. N. (1993). The essence of chaos. UCL Press.

- Luhmann, N. (1986). The autopoiesis of social systems. In F. Geyer, & J. van der Douwen (Eds.), Sociocybernetic paradoxes: observation, control and evolution of self-steering systems. Sage.

- MacIntosh, R., MacLean, D., Stacey, R., & Griffin, D. (2006). Complexity and organization: readings and conversations. Routledge.

- Maguire, S., & McKelvey, B. (1999). Complexity and management: moving from fad to firm foundations. Emergence, 1(2), 19–61.

- Makdisi, S., & Soto, R. (2023). The aftermath of the Arab uprisings. Routledge.

- Mantere, S., & Ketokivi, M. (2013). Reasoning in organization science. Academy of Management Review, 38(1), 70–89.

- Matilal, S., & Hopfl, H. (2009). Accounting for the Bhopal disaster: Footnotes and photographs. Accounting Auditing & Accountability Journal, 22(6), 953–972.

- Menifield, C. E. (2017). The basics of public budgeting and financial management: A handbook for academics and practitioners (3rd edn). Hamilton Books.

- Merriam, S. B. (1998). Qualitative research and case study applications in education. Jossey-Bass.

- Mitchell, M. (2009). Complexity: a guided tour. Oxford University Press.

- Mitleton-Kelly, E. (2003). Ten principles of complexity and enabling infrastructures. In E. Mitleton-Kelly (Ed.), Complex systems and evolutionary perspectives of organizations: the application of complexity theory to organizations. Elsevier.

- Morse, J. M., Barrett, M., Mayan, M., Olson, K., & Spiers, J. (2002). Verification strategies for establishing reliability and validity in qualitative research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 1(2), 13–22.

- National Bank of Ukraine. (2023). Inflation report. https://bank.gov.ua/ua/news/all/inflyatsiyniy-zvit-sichen-2023-roku.

- OECD. (2022a). Administrative service delivery during war time. OECD policy responses on the impacts of the war in Ukraine.

- OECD. (2022b). Turning to regions and local governments to rebuild Ukraine. OECD policy responses on the impacts of the war in Ukraine.

- OECD. (2023a). Assessing the impact of Russia’s war against Ukraine on Eastern partner countries.

- OECD. (2023b). Public procurement in the post-war reconstruction of Ukraine—main challenges. OECD Policy responses on the impacts of the war in Ukraine.

- Priya, A. (2021). Case study methodology of qualitative research: key attributes and navigating the conundrums in its application. Sociological Bulletin, 70(1), 94–110.

- Sargiacomo, M. (2015). Earthquakes, exceptional government and extraordinary accounting. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 42, 67–89.

- Sargiacomo, M., & Walker, S. P. (2022). Disaster governance and hybrid organizations: accounting, performance challenges and evacuee housing. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 35(3), 887–916.

- Schneider, M., & Somers, M. (2006). Organizations as complex adaptive systems: Implications of Complexity Theory for leadership research. The Leadership Quarterly, 17(4), 351–365.

- Serwer, D. (2019). From war to peace in the Balkans, the Middle East and Ukraine. Springer Nature.

- Sporns, O. (2016). Networks of the brain. MIT Press.

- Stacey, R. (1995). The science of complexity: an alternative perspective for strategic change processes. Strategic Management Journal, 16, 477–495.

- Sterman, J. (2000). Business dynamics: Systems thinking and modeling for a complex world with CD-ROM. McGraw-Hill Professional.

- Stewart, F. (2009). Policies towards horizontal inequalities in post-conflict reconstruction. In T. Addison, & T. Brück (Eds.), Making peace work: the challenges of social and economic reconstruction. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Teisman, G. R., & Klijn, E. H. (2008). Complexity theory and public management: An introduction. Public Management Review, 10(3), 287–297.

- Turner, J., & Baker, R. (2019). Complexity theory: an overview with potential applications for the social sciences. Department of Learning Technologies, University of North Texas.

- Uhl-Bien, M., Marion, R., & McKelvey, B. (2007). Complexity Leadership Theory: Shifting leadership from the industrial age to the knowledge era. The Leadership Quarterly, 18(4), 298–318.

- United Nations. (2009). Global assessment report on disaster risk reduction. https://www.undrr.org/publication/global-assessment-report-disaster-risk-reduction-2009.

- United Nations. (2023). UN annual results report 2022: early recovery efforts in Ukraine.

- Vakulenko, V. (2020). Roles played by global and local agents in implementing converging and diverging changes. Nord University Business School. PhD thesis, nr 79.

- Vakulenko, V. (2021). International donors as enablers of institutional change in turbulent times? Journal of Public Budgeting, Accounting & Financial Management, 34(1), 162–185.

- Vakulenko, V., Iermolenko, O., & Bourmistrov, A. (2024). Chapter 6: Addressing accountability challenges with theory of change: the case of a social partnership in Ukraine. In G. Grossi, & J. Vakkuri (Eds.), Handbook of accounting and public governance. Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Woodward, S. L. (1995). Balkan tragedy: Chaos and dissolution after the Cold War. Brookings Institution Press.

- World Bank. (1998). Post-conflict reconstruction: The role of the World Bank.

- World Bank. (1999). World development report: Entering the 21st century—development. Oxford University Press.

- World Bank. (2022). Aid, recovery, and sustainable reconstruction: Providing assistance to Ukraine in meeting immediate and medium-term economic needs. (In Ukranian.) https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/099547405052230400/pdf/IDU063b2f81900861047a70b5540e3e950f93a8c.pdf.

- World Bank, Government of Ukraine, & European Commission. (2022). Ukraine rapid damage and needs assessment.

- World Bank, Government of Ukraine, European Union, United Nations. (2023). Ukraine rapid damage and needs assessment: February 2022—February 2023.

- Yin, R. K. (2018). Case study research and applications: Design and methods (6th edn). Sage.

- Zibulewsky, J. (2001). Defining disaster: the emergency department perspective. Baylor University Medical Center Proceedings, 14(2), 144–149.