Abstract

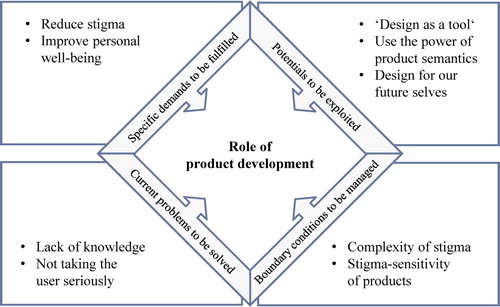

Stigma may be the Achilles’ heel of Inclusive Design, having a variety of negative effects on the user, e.g. anxiety or depression. From a product development (PD) perspective, such negative user stigmatisation can lead to the rejection of a product. PD cannot defeat stigma itself, but it can make a valuable contribution by reducing product-related stigma. Joining the battle, this contribution analyses the role of PD and identifies supports that help to reduce stigma in the respective context using an initial and a systematic literature review. The role of PD is split into four categories addressing the need to fulfil specific demands (reduce stigma and improve personal well-being), exploit potentials (see design as a tool, use the power of product semantics and design for our future selves), solve current problems (lack of knowledge and not taking the user seriously) and manage boundary conditions (complexity of stigma and the stigma-sensitivity of products). Individual, process, educational solutions or general strategies are supports that help meeting those expectations. Due to different challenges, there is still a need for action to improve those supports to deliver specific design recommendations and reduce the lack of knowledge.

Introduction

Although Inclusive Design (ID), Universal Design (UD) and Design for All (DfA) slightly differ in their focus, they are all essentially trying to address a wide range of users with only one product (Goodman-Deane, Langdon, and Clarkson Citation2010). These approaches are constantly evolving towards a broader understanding of true diversity and user needs (cf. e.g. Waller et al. Citation2015; Steinfeld Citation2013) and suggest good solutions to integrate users’ requirements but yet do not guarantee success on the market. On the one hand, to enable a concept of ‘one size fits many’, heterogeneous user groups need to be treated equally. This requires anonymisation and homogenisation of the users’ needs (Jacobson Citation2014), which often results in neutral product designs (Rønneberg Næss and Øritsland Citation2009). Such neutrality is rarely appealing to the users, which often leads to a lack of users’ acceptance. On the other hand, the context in which ID/UD/DfA is used is challenging. In many cases, the addressed products are assistive devices, which often link the prejudice of abnormality to the user (Bispo and Branco Citation2009). Both mentioned challenges may lead to negative user stigmatisation favouring product rejection (Rønneberg Næss and Øritsland Citation2009). Stockton (Citation2009) even states that stigma is the Achilles’ heel of ID. Joining the battle against stigma, this paper generally analyses the role of product development in managing product-related stigma and how existing supports can contribute to it.

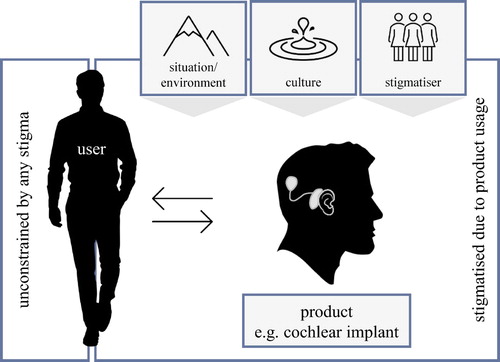

The concept of stigma is hereby versatile and complex. Goffman (Citation1963) coined the term from a sociological perspective and described it as an attribute that extensively discredits a person to be tainted and discounted instead of normal. Such attributes are often personal like a fault in character or physical abomination. Recent literature starts to open up the discussion about the cause of stigma and includes other influencing factors. van Brakel (Citation2006) adds, for instance, attitudes, discriminatory practices, services, media and materials. Bichard, Coleman, and Langdon (Citation2007) instead, understand stigma not only as an attribute but a behaviour triggered by the environment, personal circumstances or even a product. Vaes (Citation2019) also identifies the product as a driver of stigma and introduces the concept of product-related stigma (see Figure ). Whether a user is stigmatised by another person (stigmatiser) depends on the whole context of product usage including the user, the situation, culture, the stigmatiser and the product. Each aspect has different influencing factors:

the user: having or not having coping strategies, having stereotypical behaviour, personality, personal values (Vaes Citation2014) etc.

the situation/environment: social context (Shinohara and Wobbrock Citation2011), people involved or not (Vaes Citation2019), where the whole situation takes place (Major and O’Brien Citation2005) etc.

culture: cultural background of user/stigmatiser (Major and O’Brien Citation2005), cultural differences of user/stigmatiser (Yuker Citation1994) etc.

the stigmatiser: personality, personal background, attitudes and values (Vaes Citation2014), available information about the context (Yuker Citation1994) etc.

the product: visibility (Vaes Citation2014), type of product (Parette and Scherer Citation2004), stigma sensitivity (Vaes, Stappers, and Standaert Citation2016) etc.

Figure 1. Concept of product-related stigma, own illustration based on (Vaes Citation2019).

If users are stigmatised, the consequences are mostly negative. In general, the behaviour of the surrounding people towards the ones being stigmatised changes in an inappropriate manner (cf. Brookes Citation1998; Crocker, Major, and Steele Citation1998; Carneiro et al. Citation2015). Hereby, different reactions occur – people are, for example, laughed at (cf. Carneiro et al. Citation2015), insulted (cf. Vaes Citation2014) or simply less appreciated (cf. Gaffney Citation2010). This altered behaviour against people can also change their psychological well-being, e.g. in form of a reduced self-confidence (cf. Bichard, Coleman, and Langdon Citation2007; Shinohara and Wobbrock Citation2011), a changed self-awareness (cf. Wright Citation1983; Major and O’Brien Citation2005; Vaes Citation2014), a loss of self-esteem (cf. Crandall and Coleman Citation1992; Corrigan and Watson Citation2002; Major and O’Brien Citation2005; Shinohara and Wobbrock Citation2011; Vaes Citation2014), anxiety (cf. Crandall and Coleman Citation1992; Parette and Scherer Citation2004; Vaes Citation2019), depression (cf. Crandall and Coleman Citation1992) and many more.

The two main challenges from the perspective of product development are the lack of product acceptance (cf. Goffman Citation1963; Louise-Bender, Kim, and Weiner Citation2002; Jacobson Citation2014) as well as the products’ rejection (cf. Louise-Bender, Kim, and Weiner Citation2002; Parette and Scherer Citation2004; Rønneberg Næss and Øritsland Citation2009; Bichard, Coleman, and Langdon Citation2007; Shinohara and Wobbrock Citation2011; Jacobson Citation2014; Steinfeld and Smith Citation2012). Assistive technologies, such as wheelchairs, hearing aids, walkers, etc., are affected in particular, as they are often linked to disabilities and limitations (Parette and Scherer Citation2004), with which the user does not necessarily want to be associated. Besides the product type, the product shape (cf. Scherer Citation2000; Bichard, Coleman, and Langdon Citation2007; Shinohara and Wobbrock Citation2011; Vaes Citation2014; Jacobson Citation2014; Carneiro et al. Citation2018) and its visibility (cf. Bispo and Branco Citation2009; Vaes Citation2014) are of great importance. Stigma-sensitive products designed to be used invisibly usually do not cause stigmatisation. Contrary, products wouldn’t need to be hidden if the user feels safe and confident while using them (Vaes Citation2014). In some cases, hiding a product is not even possible, e.g. if the user needs a wheelchair. How stigma is perceived and how it is dealt with also depends on the user him/herself. If there are enough coping resources, he or she can successfully handle the stigma (Major and O’Brien Citation2005). However, if these resources are missing, the already mentioned negative effects may occur.

The battle against stigma is a complex, highly interdisciplinary challenge that product development alone certainly cannot solve. However, companies do have a social responsibility towards the users of their products. Product development can make a contribution to overcome stigma by trying to minimise the product-related stigma. In order to achieve this goal, there are already several methods available that contribute to different stages of the design process. Besides those that accompany the whole process and the product’s evaluation, approaches that support the designer during early design stages, like planning and clarifying the task, are especially useful to provide necessary information. Moreover, they sensitise the designer about product-related stigma and how to reduce it. Approaches that focus on the development process include, for instance, the design for social acceptance (Shinohara and Wobbrock Citation2011) or ability-based design (Wobbrock et al. Citation2011). The measurement of stigma can be carried out by using a questionnaire (Carneiro et al. Citation2018), the Product Appraisal Model for Stigma (Vaes Citation2019) or validated experimental techniques like observations (e.g. Vaes, Stappers, and Standaert Citation2016). Recommendations towards the design of products to reduce stigma are often provided via general strategies such as strengthening the individual identity of the product (Green Citation2009; Vaes Citation2019).

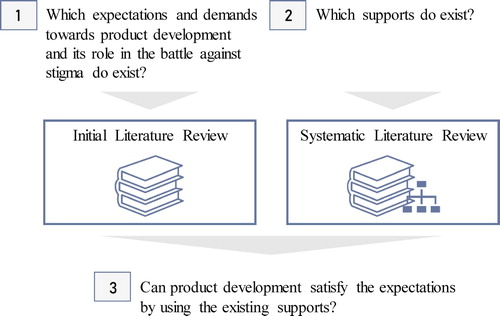

The main objective of this paper is the discussion whether product development is able to reduce product-related stigma with help of the currently available support. Thus, the three research questions that are going to be examined are as follows:

Which expectations and demands towards product development and its role in the battle against stigma do exist?

Which supports do exist?

Can product development satisfy the expectations by using the existing supports?

Methods

To properly answer the prior defined research questions an initial and a systematic literature review were conducted (see Figure ). Hereby, the scope of the initial review was more open than the systematic one as it was meant to generally gain understanding about the role of product development in the context of stigmatisation. The systematic review additionally identified existing supports to reduce product-related stigma. After that, the findings from both literature reviews were compared to discuss whether product development is able to satisfy the expectations with the supports available. Both reviews were conducted by the corresponding author, discussed by all authors and consider literature published until May 2020.

Initial literature review

The search within the initial literature review was conducted in Scopus as it is the largest database for abstracts of peer-reviewed literature. The search included scientific journal contributions, books and conference proceedings written in English. The search string examined title, abstract and keywords for the terms ‘product development’ and ‘stigma’. Synonyms and different spellings were also considered leading to the final string: ‘TITLE-ABS-KEY ((“product development” OR “engineering design” OR “product design” OR “design”) AND (“stigma” OR “stigmatization” OR “stigmatisation”))’. The paper selection started by reading the title and abstracts. To identify a paper as relevant, the inclusion criteria ‘the contribution generally deals with stigma in the context of product development’ must be met. If this was the case, the full paper was read and re-evaluated according to the inclusion criteria. The final set of contributions was further examined regarding the expected role of product development in the battle against stigma to provide answers to research question one. Thus, the authors screened the papers in terms of directly expressed expectations, demands and wishes towards product development as well as indirectly mentioned problems that necessarily be solved or potential that is not sufficiently utilised. All of the individual statements were listed, subsequently sorted according to their meaning and finally merged into four different categories.

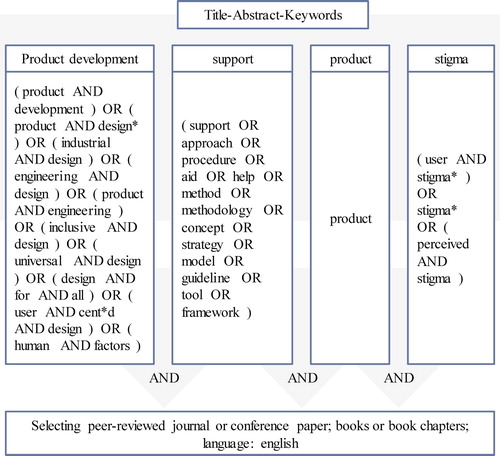

Systematic literature review

After gaining a general understanding about stigma in the respective context, the systematic literature review identified specific supports to reduce or overcome product-related stigma. Similar to the initial literature review, Scopus was the main source of contributing literature. To crosscheck the findings, the global citation database Web of Science was used. Again, the search included scientific journal contributions, books and conference proceedings written in English. The search string is illustrated in Figure .

Inclusion criteria consisted of two aspects, which both have to be met: on the one hand, the context has to be product development and on the other hand, there is at least one support against user stigma mentioned. The exclusion criteria was vice versa. Either the wrong context or the lack of a support mentioned, led to the exclusion of the contribution. The selection procedure within the review included four steps:

Preselection 1: read title, keywords and abstract | include paper if inclusion criteria ‘existing context of product development’ fits

Preselection 2: reread keywords and abstract | include if inclusion criteria ‘at least one support against user stigma is mentioned’ fits

Final Selection: read instruction and conclusion | include if both inclusion criteria fit

Read full paper | re-evaluation due to inclusion criteria

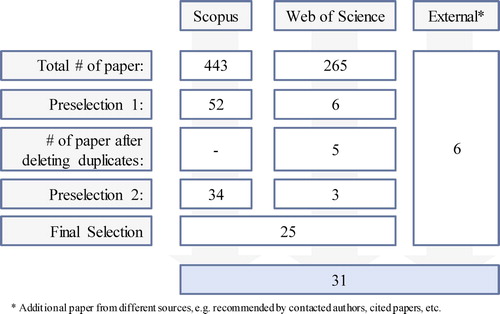

Within the systematic literature review, 31 contributions were identified (see Figure ). Besides the contributions from Scopus and Web of Science, six external papers were added due to recommendations by other researchers or citations. All papers have an academic background. None of the authors mentioned cooperation with industry. However, many papers include use cases and studies in addition to basic literature reviews. An overview of the 31 contributions including the methods used is given in detail in the Appendix.

The final set of 31 relevant contributions was then examined regarding the identification of supports to reduce or overcome product-related stigma. For this purpose, the authors listed and classified the type of support. Reliability of the contributions was mainly evaluated by assessing the methods used and the underlying data of the supports (cf. Appendix).

Results

The role of product development

Within the initial literature review, 85 relevant contributions were identified and analysed regarding the expectations towards product development. Those demands not merely come from scientists and their understanding of the topic, but also directly from people frequently facing stigma. Interviewed in various studies, they give unique insights into what is actually going wrong from the user’s perspective. We, as product developers, are often not personally affected and therefore unaware and not enough sensitised towards such a tangible topic. However, combining all different views and studies from the initial literature review, four main categories were derived to answer research question one (see Figure ).

Specific demands to be fulfilled

Reduce stigma

One of the main demands is the direct and goal-oriented reduction of stigma (Bichard, Coleman, and Langdon Citation2007). Thereby, different factors play a role, for instance access. People like to have good accessibility without perceived stigma (Covington Citation1999), regardless of whether or not personal limitations exist (Shinohara and Wobbrock Citation2011). Another important factor is aesthetics and usability. Functionality, reliability and safety are often top priority for stigma-sensitive products (e.g. assistive technology) (McCreadie and Tinker Citation2005). Unfortunately, it is not taken into account that such a product will never work well if it is neither accepted nor applied by the user (Jacobson Citation2014). Therefore, it is important to focus on an appealing and aesthetical design as well (Bichard, Coleman, and Langdon Citation2007; Li, Lee, and Xu Citation2020). A high level of product attractiveness can additionally contribute to the user’s identification with the product and can thus increase the user’s self-esteem and self-expression (Scherer Citation2000). This helps to address the personal level of the users, which in the end strengthens their self-confidence and empower them to deal with stigma more easily (Vaes Citation2014). The prevention of physical confronting moments, like people not being able to use a product because it is too heavy, is equally important (Vaes Citation2019). To achieve this, a good usability is necessary – especially for older people, who often suffer from physical impairments (Steinfeld and Smith Citation2012). Usability alone does not automatically ensure good user experience (Rebelo et al. Citation2012) and, depending on the resulting product design, can also have a negative impact on stigma. In the end, sufficient functionality should be the basis for a product with an equally good usability and an emotionally appealing product design (Scherer Citation2000). Thus, stigmatisation can be effectively reduced and a good user experience can be achieved. Another factor to reduce stigma is the need for social communication for products (Volonté Citation2010), i.e. the message a product sends out to society. Hereby, it is the responsibility of the product developer to enable a balance between his/her technical point of view and the social and personal values of the user (Vaes Citation2014).

Improve personal well-being

The second main demand is the improvement of a user’s personal well-being (Jensen Citation2009). Triggering emotions can be one possible solution to achieve this task. Products usually evoke emotions during their usage. Understanding the type of emotion enhances a better understanding of stigma (Jacobson Citation2014). For instance, it is more advisable to evoke positive emotions than negative ones to fight stigma (Sharp, Preece, and Rogers Citation2019). Such emotions can be realised, e.g. by an emotionally appealing product design tailored for the user, which, as already mentioned, can in turn lead to an increased self-confidence of the user. Personal well-being can also be increased by treating every person – disabled or not – equally (cf. Wobbrock et al. Citation2011; Shinohara and Wobbrock Citation2011). The product must therefore be able to provide users a sense of normality – let it be the pure existence of the product or which meaning is projected on the user during its usage.

Potentials to be exploited

‘Design as a tool’

One main potential in the battle against stigma is design itself with its numerous powerful and established tools. It was already mentioned, that it is beneficial to balance usability and aesthetics. If it is properly used, design has the potential to reconcile the tension between both tasks and bring them successfully together (Marti and Giusti Citation2011). Individual users can use the resulting products in turn as a tool to better fit into society or simply to better experience everyday life (Louise-Bender, Kim, and Weiner Citation2002).

Use the power of product semantics

The second main potential is the power of product semantics. Demirbilek and Sener (Citation2003) explain product semantics as ‘an attempt to identify appropriate visual, tactile and auditory messages and incorporate them into product design. […] It combines various disciplines, such as art, ergonomics, semiotics, communication, logic, philosophy, and psychology’. Using product semantics properly may lead to an emotionally appealing and intuitively usable product (Demirbilek and Sener Citation2003). Depending on the message being conveyed, the attractiveness of the product can be increased or reduced (Crilly, Moultrie, and Clarkson Citation2004). A mobile phone designed for people with motor disabilities might have big buttons and a clunky look for accessibility purposes and robustness. Yet, the message received by an average person seeing someone using the phone is not ‘this is a robust phone’ but rather ‘there is something wrong with the user’. This might not be negative at all, but it does change the way others interact with the user. Product development must be aware of the values a product transmits. This potential is vast, given that product development can also specifically influence values and attitudes through product design in a positive way (Olander Citation2011). Technology and design can thus also be used as ‘mediators of disability’ to break old structures and create new ones (Anderberg Citation2005).

Design for our future selves

Designing against stigma particularly supports people being different, e.g. because they have a different mindset, altered physical abilities or they are just getting older. In the end, anybody, including ourselves, can be affected independent of age and sex. With approaches like ID/UD/DfA, there already are methods having the potential to design for our future selves (Vaes Citation2014). This potential is not yet being exploited in practice because they are simply not used sufficiently. There are even attempts to extend the UD by an eighth principle, the principle of user equality to reduce stigma (Kaletsch Citation2009). Further alternatives for expansions of UD are emerging taking stigma into account, e.g. emotional universal design (Olander Citation2011). Even if these approaches are not yet established, the potential still exists and should be explored.

Current problems to be solved

Lack of knowledge

One major problem in the battle against stigma is the lack of knowledge about stigma, its influences and effects in product development. For example, the developer is often neither aware of the needs of people with altered abilities nor of how they can and should be integrated into the development process (Vaes Citation2014). A lack of knowledge occurs about the context of use and how affected people perceive a stigmatising product usage (Jacobson Citation2014). In the end, this may lead to a false perception of the actual user’s experience (Brookes Citation1991). This problem intensifies, if the developer and the user have strong discrepancies in their cultural values and personal preferences (Parette and Scherer Citation2004).

Not taking the user seriously

Another huge problem is that the product developer not always takes the user and his or her needs seriously (Jacobson Citation2014). Disabled people are especially endangered of being stigmatised during product usage as they are dependent on assistive devices. Those products often lag behind modern technological standards (Shinohara and Wobbrock Citation2011). Some only focus on ergonomics (Bispo and Branco Citation2009; Vaes Citation2019), others are unnecessarily difficult to use (Vaes Citation2014). Aesthetic demands and personal preferences, instead, are rarely taken into account (Shinohara and Wobbrock Citation2011; Vaes Citation2019). These are all factors that encourage stigma and must be eliminated.

Boundary conditions to be managed

Complexity of stigma

The first boundary condition is the complexity of the whole topic. For example, product semantics is mentioned as a great potential to face stigma, but it is not always under the sole control of the developer (Bispo and Branco Citation2009). Assistive technologies often communicate vulnerability or functional limitations (cf. Luborsky Citation1993; Parette and Scherer Citation2004). This association also arises from society, which makes it difficult for product development to change such established structures. In addition, products are rarely developed in a neutral way because they are usually designed by the same people in society who stigmatise (Sheldon Citation2014). Furthermore, a product alone is not solely responsible for the stigmatisation. Other influencing factors, like the situation or the cultural background, also play a role (Vaes Citation2014). Even multiple stigmatisation is possible due to social status, gender or ethnicity, etc. (Hanson Citation2004; Vaes Citation2014).

Stigma-sensitivity of products

Another boundary condition that needs to be managed is the stigma-sensitivity of products. Some products are more likely to stigmatise the user than others. Protective, assistive and medical devices, for instance, have a higher sensitivity than e.g. sports equipment (cf. Bispo and Branco Citation2009; Vaes Citation2014). Reducing stigma is much more difficult in these cases, but all the more important. Therefore, product development must decisively fight stigma in these product categories.

Existing supports to reduce product-related stigma and its benefits and challenges

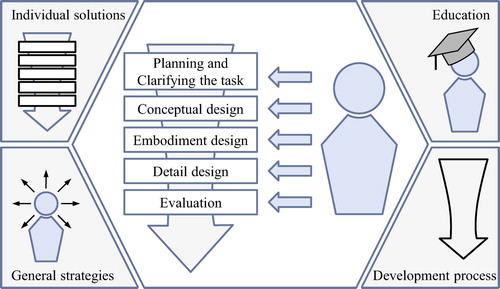

The supports identified during the systematic literature review were clustered into four categories: individual solutions, education, approaches addressing the development process and general strategies (see Figure ). The last-mentioned were not solely extracted out of the 31 papers but also from various contributions of the initial literature study as these strategies were often mentioned in short paragraphs, but not published as an independent support.

Figure 6. Overview of supports. Development process according to Pahl et al. (Citation2007).

Individual solutions

There are different individual solutions, which are applicable throughout the whole product development process (see Table ). In the early stages of product development, the available supports mostly aim for identifying requirements that have a connection to stigma. The developer can then adjust the relevant parameters in order to minimise product-related stigma. During the evaluation, measuring stigma is the main task, since this identifies the need for additional iterations in case the product-related stigma remains too high. However, there are also solutions that can be used independent throughout the whole development process.

Table 1. Overview of individual solutions.

The main benefit of the individual solutions is their independence from existing product development processes. Hence, companies can easily integrate single or a set of individual solutions that fit best into their own processes. Furthermore, in many of the presented solutions, the product developer interacts with real users (e.g. Gherardini et al. Citation2020; McCarthy, Ramírez, and Robinson Citation2017; Bright and Coventry Citation2013). On the one hand, this may sensitise the developers to better understand the problems of those being actually stigmatised. On the other hand, such data is usually biased and there is no guarantee whether the statements of the individuals are equally important to the entire target group. Additionally, finding the ‘right’ user is mandatory. In the context of stigmatisation, we have to look at people being stigmatised. As lead users might be disabled, it will be quite challenging to find people that are in fact able to contribute, e.g. in co-designing or qualitative approaches like focus groups (cf. Gherardini et al. Citation2020). We need to be aware, that working with a stigmatised person might require more time, costs and experience than classical user integration.

In addition, some individual solutions also lack a sufficient focus on stigma. While some supports are specifically designed to address stigma (e.g. Lawrence et al. Citation2010; Vaes Citation2019), there are others who see its reduction merely as a positive side effect (e.g. Bright and Coventry Citation2013; Spiru et al. Citation2019; Woodcock, Osmond, and Holliday Citation2020). This shows that although awareness of the issue is slowly increasing, it is still very low. A more practical problem is the accessibility of the solutions. Some solutions are very well documented and can easily be adapted. Lawrence et al. (Citation2010), for instance, provide the perceived stigmatisation questionnaire in the Appendix of their paper. Vaes (Citation2019) uses gamification to convey information in an understandable and playful manner. However, there are also publications in which it is not clear where some of the information comes from. Abel and Satterfield (Citation2018), for example, get their input data for the introduced divergency model from a research survey tool based on the connectivity model. It remains unclear, how this research survey tool actually works and how data is collected. This means that further effort is needed before the method can actually be used. Furthermore, qualitative approaches (like focus groups, observation, ethnography etc.) require experience to develop a study design as well as conduct the study with participants. Moreover, due to the lack of industrial applications, it is difficult to assess the actual usefulness of the methods in the respective context of product-related user stigma.

Education

Educational solutions currently relate exclusively to the training of university students. Thereby, Schneider, McDonagh, and Thomas (Citation2013) introduce a co-designing course with disabled and non-disabled. Vaes, Corremans, and Moons (Citation2011) teach empathy in different design stages, whereas Torkildsby and Vaes (Citation2019) combine critical design workshops with the stigma-free design toolkit by Vaes (Citation2019).

Educational solutions are beneficial as they increase the understanding and sensitisation of future designers, who bring knowledge into the company and thus can create change. But right now, there are only a few universities providing such courses. Therefore, the number of taught students is very small. The existing courses are also not contributing to the current misunderstanding of stigma since only university students are trained but not designers that currently work in industry. Thus, the existing situation remains unchanged.

Development process

Process solutions usually address a variety of users and can be applied to a vast amount of different products. Tools and methods used inside these processes often integrate the user directly leading to benefits and challenges that are already mentioned (see individual solutions). Besides classical approaches like ID/UD/DfA, there are also novel process solutions or extensions of those existing (see Table ).

Table 2. Overview of process solutions.

However, most of the mentioned extensions of classical approaches like UD/ID/DfA are very unspecific and rather theoretical constructs without having been used in an industrial context yet. The concept by Zöller and Wartzack (Citation2017) to add emotional satisfaction factors to the classical UD approach, for instance, was neither further developed nor used in an industrial context. Therefore, it remains a theoretical construct that is not easily adaptable by companies. This is not the only reason why it is difficult for companies to implement such processes. They may have to redesign their own development process, which can be extremely expensive. Moreover, success is not guaranteed and difficult to measure. There is also a kind of misunderstanding of the terms UD/ID/DfA. As the resulting products out of these process solutions often transport negative associations (e.g. neutral design), also the terms themselves are stigmatised negatively.

General strategies

Various strategies for reducing product-related stigma are mentioned in contributions dealing with the issue of stigma (see Table ). The strategies were divided into three main categories: product intervention, user empowerment and cultural intervention (cf. Vaes Citation2019).

Table 3. Overview of general strategies.

As the strategies are very general, they can be applied to a huge variety of different products. Applying them may improve the understanding of stigma and how to avoid it. This results in a better sensitisation of the product developer. Yet, the developer still needs prior knowledge to implement a strategy as there are no specific design recommendations and no information about the relevance of different strategies in different contexts. For instance, if a hearing aid offers the possibility to hide it, this is hardly possible for a wheelchair. Different product types require different strategies. Even a combination of different strategies can be beneficial. However, there is no weighting or ranking between the strategies. It is also unclear to what extend strategies depend on the context and especially the users and their individual preferences. In an interview conducted by Shinohara (Citation2017), for example, one participant perceived it ‘pleasant when conversations focus on mainstream technology that one can use right along with one’s peers’. Another participant of the interview instead prefers products to be attractive:

I like things attractive. Whatever adaptive equipment, I want it to look nice. […] And, as a blind person, yeah, maybe I don’t see it, but other people see it, and I want it to be, you know, just as glamorous as the next guy.

Discussion

In the following, we discuss whether the identified supports satisfy the expectations towards product development. To fulfil the specifically mentioned demands of reducing stigma and improving personal well-being, process solutions might be beneficial. However, this does cause several problems, especially the often criticised neutral design resulting from classical process solutions contradicts the desire for an emotionally appealing product design combined with good usability. Besides, the already mentioned challenges of using process solutions are very high (see section development process). A better support is offered by the use of strategies as well as some of the individual solutions (e.g. requirements/measuring stigma). However, by using them, the product developer only receives general implications instead of concrete recommendations for product design. This requires a certain degree of a priori knowledge that is often not available. The lack of background knowledge is also problematic when it comes to the desire to improve personal well-being. Here it is important to integrate tangible factors into the product design. For example, especially positive emotions should be evoked while using the product. Such soft aspects, however, have only recently been accepted as an important part of product development, if even at all. In other disciplines, however, there are approaches that can be used. One example is the research area of Affective Engineering, which is dealing with how affective user needs can be transformed into perceptible product design elements (cf. e.g. Aziz, Husni, and Jamaludin Citation2010; Norman Citation2005). In addition, the field of positive design explicitly tries to evoke certain emotions during product use (cf. e.g. Desmet Citation2002; Desmet and Pohlmeyer Citation2013). In the context of stigmatisation, such approaches have been little known so far. One reason for this may be the great interdisciplinarity of the topic. This makes it, of course, very challenging in the first instance, but it can contribute greatly to reducing stigma if methods from different research areas are better linked and used in the respective context.

To exploit the potential in the context of stigma, design as a tool, the use of product semantics and the possibility to design for our future selves are mentioned. Hereby, all three aspects interact with one another. In order to exploit the potential, they all have in common that existing methods must be accepted and applied. This is where several difficulties arise. On the one hand, many methods are not very accessible. Many strategies, for instance, are rarely structured or not published on basis of high-quality data. On the other hand, sometimes there is simply no suitable method that can be used. The consideration of product semantics is subject to this problem. Although it is mentioned in the context of single strategies, it remains unclear how it should be handled and used methodically.

Another expectation towards product development is to solve the current problem of having a lack of knowledge and not taking the user seriously. Those problems weren’t initially expected from the authors as, nowadays, more companies try to understand their users’ needs, e.g. by using user-centred design methods. Classic methods like observations or focus groups can even be found as part of the individual solutions (cf. Table ). However, in order to sufficiently use them to address stigma, designers first need to be aware of this topic. As stigma is lacking a general sensitisation in product development, available solutions remain unused. Thus, it is important to raise awareness of this issue. Not only to close the knowledge gap but also to treat stigmatised users respectfully. Educational solutions can contribute the greatest benefit here. But there are still too few of them. Strategies and individual solutions, on the other hand, sometimes have a limited ability to improve the understanding, but such methods are usually merely used when there is already an awareness of the issue. In the end, it is a vicious circle that needs a lot of educational work to escape.

Considering the boundary conditions stigma entails (its complexity and stigma-sensitivity of products), the existing methods alone are not enough. Here, again, a change in awareness of what is necessary is important, which probably cannot be achieved solely by the education of future developers. At least, stigma-sensitivity can be identified by using the available evaluation methods for stigma. But still, as it is already mentioned before, without having at least small knowledge about stigma, the individual solutions and strategies are not easy to use and implement in the development process.

The discussion shows that not only the expectations towards product development varies but also the supports that are beneficial in the respective context. The results section provides a brief overview of the individual benefits and limitations of the supports and may be a starting point to choose the right method. Still, the decision which support is useful and efficient always remains highly individual and dependent on the use case. Independent of individual weaknesses of single supports, the biggest challenge is the developers’ unawareness in combination with unspecified support. However, these circumstances can be dealt with. The aim may not necessarily be to develop another full process solution, but rather to combine concrete methods with general strategies in a way that is easy to understand and entails a positive learning effect while using them. This effect is not intended to replace fundamental educational concepts for future designers. Quite the contrary, educational approaches have to be expanded and integrated as a standard module in classical engineering courses. Still, the concept of ‘learning by doing’ can also contribute to reducing the prevailing lack of knowledge. In this context, strategies must be further investigated and individual solutions must be further or newly developed so that they can both be connected. The interdisciplinarity of the topic should additionally be used as an opportunity to implement methods from other research areas in order to overcome stigma. Furthermore, stigma should not be dismissed as a casual side effect, because in the end it can be the difference between product use and rejection.

Concluding, stigma remains complex and product development will not win this battle alone. Reducing product-related stigma, however, is an efficient contribution to actively counteract it. This is also an important signal for all users living with stigma and its negative effects every day. Joining the battle against stigma, this contribution discovered the role of product development and the currently available supports to reduce product-related stigma. As it turns out, to be able to fulfil the various expectations product development is facing, supports need to be improved and misunderstanding about stigma needs to be reduced.

Tina Schröppel http://orcid.org/0000-0001-8063-0042

Jörg Miehling http://orcid.org/0000-0002-8610-1966

Sandro Wartzack http://orcid.org/0000-0002-0244-5033

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abel, T. D., and D. Satterfield. 2018. “The Divergency Model: UX Research for and with Stigmatized and Idiosyncratic Populations.” In Human Interface and the Management of Information: Information in Applications and Services, edited by Sakae Yamamoto and Hirohiko Mori, 3–11, 10905. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Anderberg, Peter. 2005. “Making Both Ends Meet.” Disability Studies Quarterly 25 (3).

- Attaianese, E. 2011. “Special Needs in Pleasure- Based Products Design: A Case Study.” In Human Factors and Ergonomics in Consumer Product Design: Uses and Applications, edited by W. Karwowski, M. M. Soares, and N. A. Stanton, 407–418. Boca Raton: CRC Press.

- Aziz, F. A., H. Husni, and Z. Jamaludin. 2010. “Affective Engineering: What is it Actually?” In Proceedings of Knowledge Management 5th International Conference 2010, edited by F. Baharom, M. Mahmuddin, Y. Yusof, W. H. W. Ishak, and M. A. Saip, 394–398. Sintok: Universiti Utara Malaysia.

- Bichard, J.-A., R. Coleman, and P. Langdon. 2007. “Does My Stigma Look Big in This? Considering Acceptability and Desirability in the Inclusive Design of Technology Products.” In Universal Access in Human Computer Interaction. Coping with Diversity: 4th International Conference on Universal Access in Human-Computer Interaction, UAHCI 2007, Held as Part of HCI International 2007, Beijing, China, July 22–27, 2007, Proceedings, Part I, edited by Constantine Stephanidis, 622–631. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer.

- Bispo, Renate, and Vasco Branco. 2009. “Designing out Stigma: The Potential of Contradictory Symbolic Imagery.” In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Inclusive Design (Include ‘09), edited by Royal College of Art, 532–537. London: Royal College of Art, Helen Hamlyn Research Centre.

- Brandl, C., P. Rasche, C. Bröhl, S. Theis, M. Wille, C. M. Schlick, and A. Mertens. 2017. “Incentives for the Acceptance of Mobility Equipment by Elderly People on the Basis of the Kano Model: A Human Factors Perspective for Initial Contact with Healthcare Products.” In Advances in Human Factors and Ergonomics in Healthcare and Medical Devices: Proceedings of the AHFE 2017 International Conferences on Human Factors and Ergonomics in Healthcare and Medical Devices, July 17–21, 2017, The Westin Bonaventure Hotel, Los Angeles, California, USA, edited by Vincent Duffy and Nancy Lightner, 161–171. Basel: Springer International Publishing.

- Bright, A. K., and L. Coventry2013. Assistive Technology for Older Adults: Psychological and Socio-Emotional Design Requirements.

- Brookes, N. A. 1991. “Users’ Responses to Assistive Devices for Physical Disability.” Social Science & Medicine 32 (12): 1417–1424.

- Brookes, N. A. 1998. “Models for Understanding Rehabilitation and Assistive Technology.” In Designing and Using Assistive Technology: The Human Perspective, edited by David B. Gray, Louis A. Quatrano, and Morton L. Lieberman, 3–11. London: Paul H. Brookes.

- Carneiro, Luciana, Francisco Rebelo, Ernesto Filgueiras, and Paulo Noriega. 2015. “Usability and User Experience of Technical Aids for People with Disabilities? A Preliminary Study with a Wheelchair.” Procedia Manufacturing 3: 6068–6074. doi:10.1016/j.promfg.2015.07.736 .

- Carneiro, Luciana, Francisco Rebelo, Paulo Noriega, and J. Faria Pais. 2018. “Could the Design Features of a Wheelchair Influence the User Experience and Stigmatization Perceptions of the Users?” In Advances in Ergonomics in Design, edited by Francisco Rebelo and Marcelo Soares, Vol. 588, 841–850. Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Choi, S. 2006. Emotional Universal Design – Beyond Usability of Products. Design and Emotion, Chalmers University of Technology, Department of Product and Production Development. In Proceedings from the 5th International Conference on Design & Emotion 2006, edited by M. Karlsson, P. Desmet, and J. van Erp. Gothenburg: Chalmers Univ. of Technology.

- Corrigan, Patrick W., and Amy C. Watson. 2002. “The Paradox of Self-Stigma and Mental Illness.” Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice 9 (1): 35–53. doi:10.1093/clipsy.9.1.35 .

- Covington, George A. 1999. “The Trojan Horse of Design.” Disability Issues 19 (1).

- Crandall, Christian S., and Robert Coleman. 1992. “Aids-Related Stigmatization and the Disruption of Social Relationships.” Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 9 (2): 163–177. doi:10.1177/0265407592092001 .

- Crilly, Nathan, James Moultrie, and P. John Clarkson. 2004. “Seeing Things: Consumer Response to the Visual Domain in Product Design.” Design Studies 25 (6): 547–577. doi:10.1016/j.destud.2004.03.001.

- Crocker, J., B. Major, and C. Steele. 1998. “Social Stigma.” In The Handbook of Social Psychology, edited by Daniel T. Gilbert, Susan T. Fiske, and Gardner Lindzey, 504–553. Boston: McGraw-Hill.

- de Barros, Ana C., Carlos Duarte, and Jose B. Cruz. 2011. “The Influence of Context on Product Judgement – Presenting Assistive Products as Consumer Goods.” International Journal of Design 5 (3): 99–112.

- Demirbilek, Oya, and Bahar Sener. 2003. “Product Design, Semantics and Emotional Response.” Ergonomics 46 (13–14): 1346–1360. doi:10.1080/00140130310001610874 .

- Desmet, Pieter. 2002. Designing Emotions. Delft: Delft University of Technology.

- Desmet, P. M. A., and A. E. Pohlmeyer. 2013. “Positive Design: An Introduction to Design for Subjective Well-Being.” International Journal of Design 7 (3): 5–19. Accessed February 19, 2018.

- Gaffney, Clare. 2010. “An Exploration of the Stigma Associated with the use of Assisted Devices.” Socheolas: Limerick Student Journal of Sociology 3 (1): 67–78.

- Gherardini, Francesco, Andrea Petruccioli, Enrico Dalpadulo, Valentina Bettelli, Maria T. Mascia, and Francesco Leali. 2020. “A Methodological Approach for the Design of Inclusive Assistive Devices by Integrating Co-Design and Additive Manufacturing Technologies.” In Intelligent Human Systems Integration 2020, edited by Tareq Ahram, Waldemar Karwowski, Alberto Vergnano, Francesco Leali, and Redha Taiar, Vol. 1131, 816–822. Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Goffman, Erving. 1963. Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity. London: Penguin.

- Goodman-Deane, Joy, Patrick Langdon, and John Clarkson. 2010. “Key Influences on the User-Centred Design Process.” Journal of Engineering Design 21 (2–3): 345–373. doi:10.1080/09544820903364912 .

- Green, Gill. 2009. The End of Stigma? Changes in the Social Experience of Long-Term Illness. London: Routledge.

- Grieg, J., M. M. Keitsch, and C. Boks. 2014. “Widening the Interpretation of Assistive Devices – A Designer’s Approach to Assistive Technology.” In Proceedings of NordDesign 2014 Conference, edited by M. Laakso and K. Ekman, 303–314. Aalto: Aalto University.

- Hanson, Julienne. 2004. “The Inclusive City: Delivering a More Accessible Urban Environment Through Inclusive Design.” In Proceedings of Cobra 2004, the International Construction Conference: Responding to Change, edited by Robert Ellis and Malcom Bell, 1–39. London: RICS Foundation.

- Hyung, J. O., C. K. Hyo, H. Hwan, and G. J. Yong. 2013. User Centered Inclusive Design Process: A ‘Situationally-Induced Impairments and Disabilities’ Perspective 8004 LNCS.

- Jacobson, Susanne. 2014. Personalised Assistive Products: Managing Stigma and Expressing the Self. Aalto: Aalto University School of Arts, Design and Architecture.

- Jensen, Lilly. 2009. “User Perspective on Assistive Technology: A Qualitative Analysis of 55 Letters from Citizens Applying for Assistive Technology.” In Assistive Technology from Adapted Equipment to Inclusive Environments, edited by P. L. Emiliani, L. Burzgali, A. Como, F. Gabbanini, and A.-L. Salminen, 589–559. Amsterdam: IOS Press.

- Kaletsch, Konrad. 2009. “The Eighth Principle of Universal Design.” Design for All Institute of India 4 (3): 66–72.

- Kang, Sunghyun, and Debra Satterfield. 2009. “Connectivity Model: Evaluating and Designing Social and Emotional Experiences.” In Proceedings of IASDR2009: Design Rigor & Relevance, edited by Korea Society of Design Science, 2247–2256. Sungnam: Korea Design Center.

- Lawrence, John W., Laura Rosenberg, Ruth B. Rimmer, Brett D. Thombs, and James A. Fauerbach. 2010. “Perceived Stigmatization and Social Comfort: Validating the Constructs and Their Measurement Among Pediatric Burn Survivors.” Rehabilitation Psychology 55 (4): 360–371. doi:10.1037/a0021674 .

- Li, Chen, Chang-Franw Lee, and Song Xu. 2020. “Stigma Threat in Design for Older Adults: Exploring Design Factors that Induce Stigma Perception.” Int. J. Des. 14 (1): 51–64.

- Louise-Bender, Pape T., J. Kim, and B. Weiner. 2002. “The Shaping of Individual Meanings Assigned to Assistive Technology: a Review of Personal Factors.” Disability and Rehabilitation 24 (1–3): 5–20. doi:10.1080/09638280110066235 .

- Luborsky, Mark R. 1993. “Sociocultural Factors Shaping Technology Usage: Fulfilling the Promise.” Technology and Disability 2 (1): 71–78. doi:10.3233/TAD-1993-2110 .

- Major, Brenda, and Laurie T. O’Brien. 2005. “The Social Psychology of Stigma.” Annual Review of Psychology 56: 393–421. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.56.091103.070137 .

- Marti, Patrizia, and Leonardo Giusti. 2011. “Bringing Aesthetically-Minded Design to Devices for Disabilities.” In Proceedings of the 2011 Conference on Designing Pleasurable Products and Interfaces, edited by Alessandro Deserti, Francesco Zurlo, and Francesca Rizzo, 1–8. New York: ACM.

- McCarthy, G. M., E.R.R. Ramírez, and B. J. Robinson. 2017. “Participatory Design to Address Stigma with Adolescents and Young Adults with Type 1 Diabetes.” In DIS 2017 – Proceedings of the 2017 ACM Conference on Designing Interactive Systems, edited by O. Mival, M. Smyth, and P. Dalsgaard, 83–94. New York: Association for Computing Machinery.

- McCreadie, Claudine, and Anthea Tinker. 2005. “The Acceptability of Assistive Technology to Older People.” Ageing and Society 25 (1): 91–110. doi:10.1017/S0144686X0400248X .

- McNeill, A., and L. Coventry. 2015. An Appraisal-Based Approach to the Stigma of Walker-Use. Cham: Springer Verlag.

- Molenbroek, J.F.M., T.J.J. Groothuizen, and R. de Bruin. 2011. Design for All: Not Excluded by Design. With the Assistance of J. F. M. Delft, R. de Bruin, and J. Mantas, Assistive Technology Research Series 27.

- Moody, L., and A. J. Cobley. 2020. MATUROLIFE: Using Advanced Material Science to Develop the Future of Assistive Technology. Cham: Springer.

- Norman, Donald A. 2005. Emotional Design: Why We Love (or Hate) Everyday Things. New York: Basic Books.

- Olander, Elin. 2011. Design as Reflection. Lund: Lund University.

- Pahl, Gerhard, Wolfgang Beitz, Jörg Feldhusen, and Karl-Heinrich Grote. 2007. Engineering Design. London: Springer London.

- Parette, Phil, and Marcia Scherer. 2004. “Assistive Technology Use and Stigma.” Education and Training in Developmental Disabilities 39 (3): 217–226.

- Partheniadis, Konstantinos, and Modestos Stavrakis. 2019. “Design and Evaluation of a Digital Wearable Ring and a Smartphone Application to Help Monitor and Manage the Effects of Raynaud’s Phenomenon.” Multimedia Tools and Applications 78 (3): 3365–3394. doi:10.1007/s11042-018-6514-3 .

- Rebelo, Francisco, Paulo Noriega, Emília Duarte, and Marcelo Soares. 2012. “Using Virtual Reality to Assess User Experience.” Human Factors 54 (6): 964–982. doi:10.1177/0018720812465006 .

- Renda, G., S. Jackson, B. Kuys, and T. W. A. Whitfield. 2016. “The Cutlery Effect: Do Designed Products for People with Disabilities Stigmatise Them?” Disability and Rehabilitation: Assistive Technology 11 (8): 661–667. doi:10.3109/17483107.2015.1042077 .

- Rønneberg Næss, Ingrid, and Trond A. Øritsland. 2009. “Inclusive, Mainstream Products.” In Inclusive Buildings, Products and Services: Challenges in Universal Design, edited by Tom Vavik, 182–191. Trondheim: Tapir.

- Scherer, Marcia J. 2000. Living in the State of Stuck: How Assistive Technology Impacts the Lives of People with Disabilities. Cambridge: Mass. Brookline Books.

- Schneider, Sheila M., Deana McDonagh, and Joyce K. Thomas. 2013. “Disability + Relevant Design: a Portfolio of Approaches.” In Design Education – Growing Our Future: Proceedings of the 15th International Conference on Engineering and Product Design Education, Dublin, Dublin Institute of Technology, Bolton Street, Dublin, Ireland, 5th to 6th September 2013, edited by Erik Bohemia, William Ion, Ahmed Kovacevic, John Lawlor, Mark McGrath, Chris McMahon, Brian Parkinson, Ger Reilly, Michael Ring, Robert Simpson, David Tormey, 440–445. Westbury, Wiltshire, UK: Institution of Engineering Designers; The Design Society.

- Sharp, Helen, Jennifer Preece, and Yvonne Rogers. 2019. Interaction Design: Beyond Human-Computer Interaction. 5th ed. Hoboken: Wiley & Sons.

- Sheldon, Alison. 2014. “Changing Technology.” In Disabling Barriers – Enabling Environments, edited by John Swain, Sally French, Colin Barnes, and Carol Thomas, 3rd ed., 173–180. Los Angeles: SAGE.

- Shinohara, Kristen. 2017. “Design for Social Accessibility: Incorporating Social Factors in the Design of Accessible Technologies.” Dissertation.

- Shinohara, Kristen, and Jacob O. Wobbrock. 2011. “In the Shadow of Misperception: Assistive Technology use and Social Interactions.” In CHI 2011: Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, edited by Desney Tan, Geraldine Fitzpatrick, Carl Gutwin, Bo Begole, and Wendy A. Kellogg, 705–714. New York, NY: ACM.

- Spiru, L., M. Marzan, C. Paul, M. Velciu, and A. Garleanu. 2019. “The Reversed Moscow Method. A General Framework for Developing age-Friendly Technologies.” In Multi Conference on Computer Science and Information Systems, MCCSIS 2019 – Proceedings of the International Conference on e-Health 2019, edited by, edited by M. Macedo and L. Rodrigues, 75–81. Lisbon: IADIS Press.

- Steinfeld, Edward.2013. “Creating an Inclusive Environment.” In Trends in Universal Design: An Anthology with Global Perspectives, Theoretical Aspects and Real World Examples, edited by Norwegian Directorate for Children, Youth and Family Affairs. Tønsberg: The Delta Centre, 52–57.

- Steinfeld, Edward, and Roger O. Smith. 2012. “Universal Design for Quality of Life Technologies.” Proceedings of the IEEE 100 (8): 2539–2554. doi:10.1109/JPROC.2012.2200562 .

- Stockton, Glynn. 2009. “Stigma: Addressing Negative Associations in Product Design.” In Creating a Better World: Proceedings of the 11th Engineering and Product Design Education Conference, Brighton, edited by A. Clarke, C. McMahon, W. Ion, and P. Hogarth, 546–551. Glasgow: The Design Society.

- Thomas, J., and D. McDonagh. 2013. “Empathic Design: Research Strategies.” Australasian Medical Journal 6 (1): 1–6.

- Torkildsby, A. B., and K. Vaes. 2019. “Addressing the Issue of Stigma-Free Design Through Critical Design Workshops.” In Towards a New Innovation Landscape: Proceedings of the 21st International Conference on Engineering and Product Design Education, Department of Design, Manufacture and Engineering Management, University of Strathclyde, United Kingdom, 12th to 13th September 2019, edited by Erik Bohemia, Ahmed Kovačević, Lyndon Buck, Ross Brisco, Dorothy Evans, Hilary Grierson, William J. Ion, and Robert I. Whitfield, 1–6. Glasgow: The Design Society; Institution of Engineering Designers.

- Vaes, Kristof. 2014. “Product Stigmaticity: Understanding, Measuring and Managing Product-Related Stigma.” Dissertation.

- Vaes, K. 2019. “Design for Empowerment, the Stigma-Free Design Toolkit.” In Proceedings of the 20th Congress of the International Ergonomics Association (IEA 2018), edited by Sebastiano Bagnara, Riccardo Tartaglia, Sara Albolino, Thomas Alexander, and Yushi Fujita, Vol. 824, 1012–1030. Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Vaes, K., J. Corremans, and I. Moons. 2011. “Educational Model for Improved Empathy: ‘The Pleasure Mask Experience’.” In Design Education for Creativity and Business Innovation: The 13th International Conference on Engineering and Product Design Education, City University London, UK, 8–9 September 2011, edited by Lyndon Buck, Peter Hogarth, and Ahmed Kovacevic, 227–232. Glasgow: The Design Society.

- Vaes, Kristof, Pieter J. Stappers, and Achiel Standaert. 2012. “Stigma-Free Product Design: An Exploration in Dust Mask Design.” In Design Education for Future Wellbeing: Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on Engineering and Product Design Education, Artesis University College, Antwerp, Belgium 6th-7th September 2012, edited by L. Buck, G. Frateur, W. Ion, C. McMahon, C. Baelus, G. de Grande, and S. Vervulgen, 141–146. Wiltshire: The Design Society.

- Vaes, Kristof, Pieter J. Stappers, and Achiel Standaert. 2016. “Measuring Product-Related Stigma in Design.” In Proceedings of DRS2016: Design + Research + Society, edited by Peter Lloyd and Erik Bohemia, 3329–3348. London: Design Research Society.

- Vaes, K., P. J. Stappers, A. Standaert, and K. Desager. 2012. Contending Stigma in Product Design Using Insights from Social Psychology as a Stepping Stone for Design Strategies.

- van Brakel, Wim H. 2006. “Measuring Health-Related Stigma – a Literature Review.” Psychology, Health & Medicine 11 (3): 307–334. doi:10.1080/13548500600595160 .

- Volonté, Paolo. 2010. “Communicative Objects.” In Design Semiotics in use, edited by Susann Vihma, 112–128. Helsinki: Aalto University.

- Waller, Sam, Mike Bradley, Ian Hosking, and P. J. Clarkson. 2015. “Making the Case for Inclusive Design.” Applied Ergonomics 46: 297–303. doi:10.1016/j.apergo.2013.03.012 .

- Wobbrock, Jacob O., Shaun K. Kane, Krzysztof Z. Gajos, Susumu Harada, and Jon Froehlich. 2011. “Ability-Based Design: Concept, Principles, Examples.” ACM Trans. Access. Comput. 3 (3): 1–27.

- Woodcock, A., J. Osmond, and N. Holliday. 2020. The Development of a Feature Matrix for the Design of Assistive Technology Products for Young Older People. Cham: Springer.

- Wright, Beatrice A. 1983. Physical Disability: A Psychological Approach. New York: Harper & Row.

- Wu, Y.-H., J. Wrobel, M. Cornuet, H. Kerhervé, S. Damnée, and A.-S. Rrigaud. 2014. “Acceptance of an Assistive Robot in Older Adults: A Mixed-Method Study of Human-Robot Interaction Over a 1-Month Period in the Living lab Setting.” Clinical Interventions in Aging 9: 801–811. doi:10.2147/CIA.S56435 .

- Yuker, H. E. 1994. “Variables That Influence Attitudes Toward People with Disabilities: Conclusions from the Data.” Journal of Social Behavior & Personality 9 (5): 3–22.

- Zöller, S. G., and S. Wartzack. 2017. “Universal Design-an old-Fashioned Paradigm?” In Emotional Engineering, edited by S. Fukuda, Vol. 5, 55–67. Basel: Springer International Publishing.