Abstract

Purpose: Data are lacking on the burden of chronic idiopathic urticaria (CIU) versus other dermatologic conditions. This analysis compared the burden of chronic urticaria (CU, proxy for CIU) with psoriasis.

Methods: Data from CU (N = 747) and psoriasis patients (N = 5107) came from 2010 to 2012 US National Health and Wellness Surveys. Outcomes included SF-12v2/SF-36v2 mental and physical component summary scores (MCS and PCS, respectively) and other health/activity-related measures.

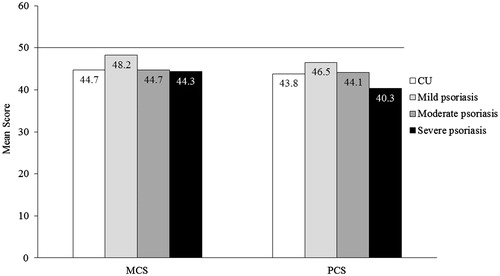

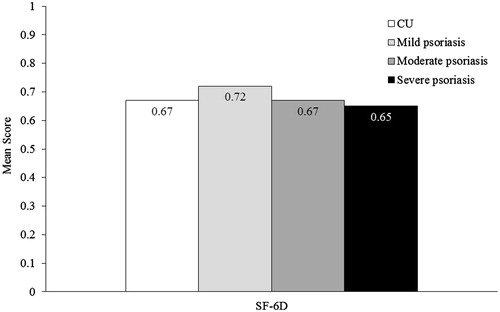

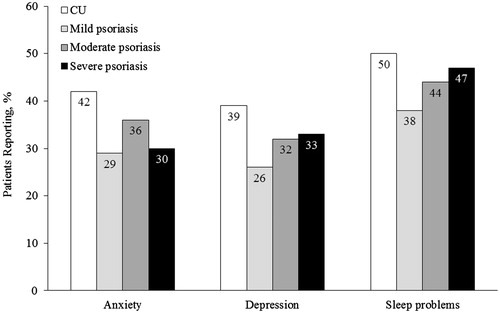

Results: MCS score was 44.7 for CU, and 48.2, 44.7 and 44.3 for mild/moderate/severe psoriasis, respectively (US norm = 50). PCS score was 43.8 for CU, and 46.5, 44.1 and 40.3 for mild/moderate/severe psoriasis. Health utility score was 0.67 for CU, and 0.72, 0.67 and 0.65 for mild/moderate/severe psoriasis. More CU patients reported depression (39%), anxiety (42%) and sleep difficulties (50%) than psoriasis patients (any severity). Overall work impairment was 29% for CU, and 19%, 26% and 31% for mild/moderate/severe psoriasis. Activities impairment was 39% for CU, and 28%, 37% and 43% for mild/moderate/severe psoriasis. CU and psoriasis patients had frequent healthcare visits.

Conclusions: Patients with CU had impaired mental/physical health and work/non-work activities, similar to moderate-to-severe psoriasis patients. Results suggest that better disease management of CU is needed. This analysis should also reflect the significant burden of CIU.

Introduction

Chronic urticaria (CU) is characterized by itchy red hives/wheals that persist for more than six weeks (Citation1). Chronic idiopathic urticaria (CIU; also known as chronic spontaneous urticaria) excludes all underlying causes of CU and represents the vast majority of CU cases (66–93%) (Citation2). Based on the few available studies, the estimated prevalence of CIU is approximately 0.5%–1.0% in the general population (Citation2). First-line recommended treatment for CIU is continuous H1 antihistamine (Citation1,Citation3). However, up to 60% of patients remain uncontrolled with H1 antihistamines, even at higher than approved doses (Citation4). For these patients, recommended add-on therapies differ between United States and international guidelines but could include first generation H1 antihistamines, H2 antihistamines, montelukast, omalizumab, immunosuppressants like cyclosporine A, or other anti-inflammatory agents including hydroxychloroquine, sulfasalazine and dapsone (Citation1,Citation3).

CIU is not life-threatening, but has been demonstrated to have a substantial impact on the physical and psychological health of patients (Citation5,Citation6). Furthermore, symptoms last more than five years in up to 14% of patients, which suggests a long-term impact of this disorder (Citation7) In the National Health and Wellness Survey (NHWS), United States and European patients with CU (survey did not evaluate CIU) treated with prescription medications were found to have substantially lower health-related quality of life (HRQL), greater work impairment and a greater prevalence of depression, anxiety and sleep problems when compared with matched controls who never experienced CU (Citation8,Citation9). Data quantifying the mental, physical, and healthcare resource burden of CU, or its most common form, CIU, compared with other dermatological conditions known to impact HRQL are lacking. To this end, psoriasis was chosen as the benchmark dermatological condition in the current analysis. Psoriasis is a chronic skin disorder characterized by scaly, itchy and painful skin lesions. Studies have demonstrated that patients with psoriasis have a reduced HRQL, and display psychological issues such as depression (Citation10–12).

Compared with well-characterized dermatological disorders, such as psoriasis, the burden of illness and need for treatment in CIU may not be as acknowledged by physicians and payers. The objective of this analysis was to evaluate the burden of illness associated with CIU (using CU as a proxy) according to patient-reported outcomes in US adults compared with psoriasis of varying severity levels.

Methods

Study design and data source

This was a retrospective, cross-sectional analysis of self-reported data collected from the NHWS in the United States in 2010, 2011 and 2012. The NHWS is a self-administered internet-based questionnaire from a sample of adults in various countries designed to reflect health in the general population (Citation13). The protocol and questionnaire for the NHWS was approved by Essex Institutional Review Board (Lebanon, NJ). Comparisons of patients with CU treated with prescription medications and matched non-CU controls within the NHWS in the United States and Europe have been previously presented (Citation8,Citation9).

Patient selection and characterization

Potential NHWS respondents were identified through participation in opt-in survey panels, with stratified random sampling within the survey panel to ensure a representative sample in terms of age, sex and white versus nonwhite race. For respondents who completed the survey more than once, the most recent response was used. Respondents were required to be ≥18 years of age, be able to read and write English, and provide informed consent. The current study included respondents who reported ever having had physician-diagnosed CU or psoriasis; respondents who reported both conditions were excluded. The survey asked the respondent to indicate which conditions he/she had ever experienced from a provided list; respondents who indicated experiencing a condition were then asked if that condition had been diagnosed by a healthcare provider. “Psoriasis” was listed as “psoriasis” whereas CU was listed as “chronic hives (experiencing six weeks or more)”. Those respondents who indicated being diagnosed CU served as the proxy cases for CIU, since this latter diagnosis was not specifically assessed in the NHWS. Information was also collected on demographics, general health characteristics, and comorbidities. The Charlson comorbidity index (CCI) was calculated from self-reported diagnosed conditions.

Respondents with psoriasis were also asked about severity (mild versus moderate versus severe), which was assessed using a question that asks respondents to consider the proportion of their body surface area (BSA) affected by psoriasis, using the palm of their hand as 1% to assist them in estimation. The 2010 and 2011 items indicated categories as mild (<2% BSA), moderate (2–10% BSA), and severe (>10% BSA). The 2012 survey had a 1% higher threshold for moderate psoriasis consistent with National Psoriasis Foundation categories: (Citation14) mild (<3% BSA), moderate (3–10% BSA), and severe (>10% BSA). Differences in the distributions using the different cutoffs were minor across years, so the categories were combined for analysis. Severity was not assessed for CU patients in the surveys.

Assessments and variables

The 2010 and 2011 NHWS surveys included the standard recall form (four-week recall period) of the revised Medical Outcomes Study 12-Item Short Form Survey Instrument (SF-12v2), which is a multipurpose, general (not disease-specific) health status instrument comprised of 12 questions (Citation15). Two summary scores are calculated from the responses, the physical component summary (PCS) and the mental component summary (MCS) scores. The 2012 survey included the Short Form 36 version 2 (SF-36v2) (Citation16), which contains the same metrics as the SF-12v2, allowing data from all three years to be pooled for analysis. PCS and MCS summary scores have a mean of 50 and a standard deviation of 10 for the US population.

Health state utilities were generated through application of the SF-6D, which utilizes six items from the SF-12v2 (Citation17). The SF-6D is a preference-based single index measure for health using UK general population values. The SF-6D index has interval scoring properties and yields summary scores on a theoretical 0–1 scale. Higher scores indicate better quality of life.

Survey respondents were asked to indicate whether they had experienced depression, sleep problems (i.e. insomnia and/or sleep difficulties), and different types of anxiety (i.e. anxiety, general anxiety disorder, panic disorder, phobia, post-traumatic stress and obsessive compulsive disorder) in the past 12 months.

The impact of CU or psoriasis on labor force participation was measured by coding employment status as currently in the labor force (full-time employed, part-time employed, self-employed, or unemployed but looking for work) versus not currently in the labor force (retired, disabled, unemployed and not looking for work, etc.).

Work productivity and activity impairment was assessed using the Work Productivity and Activity Impairment – General Health (WPAI-GH) questionnaire, a six-item validated instrument which consists of four metrics: absenteeism (the percentage of work time missed because of one's health in the past seven days), presenteeism (the percentage of impairment experienced while at work in the past seven days because of one's health), overall work productivity loss (an overall work impairment estimate that is a combination of absenteeism and presenteeism), and activity impairment (the percentage of impairment in daily activities because of one's health in the past seven days) (Citation18). Only respondents who reported being full-time, part-time, or self-employed provided data for absenteeism, presenteeism, and overall work impairment. All respondents provided data for activity impairment.

Healthcare resource use was measured by the number of office visits and the proportion of patients with office visits to traditional medical providers during the previous six months. Traditional providers were defined as primary care providers, allergists, dermatologists, psychiatrists, psychologist/psychotherapists, and “other” traditional providers. The proportion of patients who visited nontraditional providers was also assessed, although the number of visits was not captured in the survey. Nontraditional providers included herbalists, acupuncturists, chiropractors, nutritionists, and massage therapists. In addition, the number of all-cause emergency room (ER) visits and hospitalizations, and the proportion of respondents with ER visits and hospitalizations, in the previous six months was assessed.

Statistical analyzes

Descriptive statistics were provided for all assessments for patients with CU, and for patients with varying severity of psoriasis, respectively. Means and standard deviations were calculated for continuous and count variables, and percentages and frequencies were calculated for categorical variables. All analyzes were conducted using SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

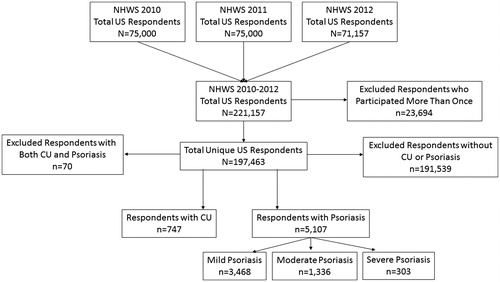

Approximately 75,000 NHWS respondents answered the survey in the United States each year, giving a total of 221,157 respondents () in three years (2010, 2011 and 2012). Of these, 747 unique respondents reported CU and 5107 reported psoriasis (n = 3468 mild, n = 1336 moderate, and n = 303 severe). Overall, a higher proportion of patients with CU were women compared to patients with psoriasis (74% versus 49%, respectively). Patients with CU were slightly younger than patients with psoriasis (mean 50.5 y versus 52.6 y, respectively), were less likely to be obese, were more likely to have never smoked, and were more likely to have exercised in the past month (). Concomitant nasal allergies, dermatologic conditions other than CU or psoriasis, severe allergic asthma and dyspepsia were more common in patients with CU compared to patients with psoriasis. The overall CCI was higher in patients with CU compared to patients with psoriasis (mean 1.1 versus 0.8, respectively). Several factors appeared to correspond to the severity of psoriasis, including obesity, current smoking status, lack of exercise and the presence of autoimmune conditions and severe allergic asthma ().

Figure 1. Flow chart of respondent selection. CU: chronic urticaria; NHWS: National Health and Wellness survey.

Table 1. Patient demographics, characteristics and comorbidities.

Health-related quality of life

The MCS score (mean ± SD) among CU (44.7 ± 12.3), moderate psoriasis (44.7 ± 12.0), and severe psoriasis (44.3 ± 12.0) indicated markedly lower mental health scores than the US norm of 50 (. The mental health status of patients with mild psoriasis was slightly lower than the US norm, with a mean MCS score of 48.2 ± 10.9. The PCS scores (mean ± SD) indicated physical status among patients with CU and psoriasis were also lower than the US norm, at 43.8 ± 12.4 for CU patients, and 46.5 ± 11.1, 44.1 ± 11.5 and 40.3 ± 13.1 for mild, moderate and severe psoriasis, respectively (. The SF-6D utility score (mean ± SD) of CU patients (0.67 ± 0.15) was similar to moderate psoriasis patients (0.67 ± 0.14; . The SF-6D utility score of CU patients was lower than that of patients with mild psoriasis (0.72 ± 0.14), indicating a lower HRQL, and higher than that of patients with severe psoriasis (0.65 ± 0.16).

Self-reported anxiety, depression, and sleep problems

The proportions of patients with CU who reported mental health or sleep problems were higher compared to patients with psoriasis (. Anxiety in the previous 12 months was reported by 42% of CU patients, and 29%, 36% and 30% of mild, moderate, and severe psoriasis patients, respectively. Depression was reported by 39% of CU patients, and 26%, 32% and 33% of mild, moderate and severe psoriasis patients. Sleep problems were reported by half (50%) of CU patients, and 38%, 44% and 47% of mild, moderate and severe psoriasis patients, respectively.

Figure 4. Self-reported anxiety, depression, and sleep problems in the previous 12 months in patients with CU and psoriasis. Sleep problems included insomnia and/or sleep difficulties; anxiety included different types of anxiety (i.e. anxiety, general anxiety disorder, panic disorder, phobia, post-traumatic stress and obsessive compulsive disorder). CU: chronic urticaria.

Labor force participation

The proportions of patients who were employed was similar among patients with CU (56%) and patients with mild, moderate and severe psoriasis (57%, 58% and 54%, respectively).

Work and non-work activity impairment

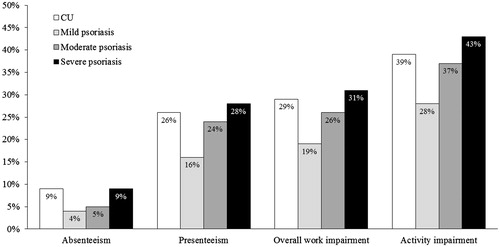

The impact of CU on work productivity was substantial and fell between moderate and severe psoriasis (. Absenteeism for the previous seven days was 9% in patients with CU, and 4%, 5% and 9% in patients with mild, moderate and severe psoriasis, respectively; presenteeism was 26% in patients with CU, and 16%, 24% and 28% in patients with mild, moderate and severe psoriasis. Mean overall work impairment of 29% was observed for patients with CU, and 19%, 26% and 31% of patients with mild, moderate and severe psoriasis. Mean impairment of activities was also substantial, with 39% for CU, and 28%, 37% and 43% for mild, moderate, and severe psoriasis (.

Figure 5. Work productivity and activity impairment in patients with CU and psoriasis. Absenteeism was defined as the percentage of work time missed because of one's health in the past seven days, presenteeism was defined as the percentage of impairment experienced while at work in the past seven days because of one's health, and overall work impairment is an overall impairment estimate that is a combination of absenteeism and presenteeism. Activity impairment was defined as the percentage of impairment in daily activities because of one's health in the past seven days. CU: chronic urticaria.

Healthcare resource utilization

Patients with CU and psoriasis were frequent users of traditional healthcare resources, with 7.1 mean healthcare visits in the past six months for CU, and 5.2, 5.6 and 6.6 mean healthcare visits for patients with mild, moderate and severe psoriasis (). The proportions of patients with visits to traditional healthcare providers were 92% of patients with CU, and 88% for each of the subgroups of patients with psoriasis. Patients with CU averaged 0.3 visits to allergists, 0.4 visits to psychiatrists, and 0.6 visits to psychologist/psychotherapists in the previous six months, whereas patients with psoriasis had 0.1, 0.2–0.3 and 0.3–0.5 visits to allergists, psychiatrists, and psychologist/psychotherapists, respectively (). The proportion of patients with CU who sought nontraditional healthcare was 22%, and was 17%, 16% and 15% in patients with mild, moderate and severe psoriasis ().

Table 2. Healthcare resource use in patients with CU and psoriasis.

The mean number of ER visits per patient in the previous six months was 0.4 for patients with CU, and 0.2, 0.3 and 0.2 in patients with mild, moderate and severe psoriasis, respectively. The mean number of hospitalizations per patient in the previous six months was 0.3 for patients with CU, whereas patients with mild, moderate, and severe psoriasis had 0.1, 0.2 and 0.1 hospitalizations.

Discussion

This analysis demonstrated that CU had a negative impact on mental and physical HRQL using patient-reported responses to a general nationwide health survey in the United States. The level of impairment in mental status scores was similar between CU and moderate and severe psoriasis patients. The physical impairment reflected by PCS scores was similar between CU and moderate psoriasis, but was greatest for severe psoriasis patients. More patients with CU reported depression, anxiety and sleep difficulties compared with psoriasis of any severity. CU was associated with reduced work and non-work activities, with levels observed between those with moderate and severe psoriasis. Healthcare resource use was common in CU and psoriasis patients. Considering the chronic nature of CU, with symptoms that can persist or recur for years (Citation7), the data indicate that the burden of illness with CU is substantial and may be comparable to moderate or severe psoriasis.

The characteristics of patients with CU in the current analysis were consistent with those previously described in the literature. For example, in the current analysis, 74% of patients with CU were women. This finding is consistent with retrospective database analyzes and other surveys where up to 70% of patients with CU and CIU were women (Citation19,Citation20). In addition, in the current analysis, 46% of patients with CU reported a history of nasal allergies, which was greater than the overall 28% of patients with psoriasis, and is comparable to the 43% of patients in the United States with CIU who reported a history of allergic rhinitis in a retrospective database analysis (Citation19).

HRQL in patients with CU was found to be similar to moderate psoriasis, and below the US norm. The results in the current study support the findings in the study by Grob et al. that compared the HRQL of 1161 patients with CU, psoriasis and atopic dermatitis using a validated HRQL instrument (VQ-Dermato) and adjusting for sex, age and severity of the disorder (Citation21). Compared with psoriasis, CU patients reported a significantly greater impact on daily living activities and physical discomfort domains, whereas psoriasis patients were more impacted on self-perception, leisure activities, social functioning and treatment-induced restrictions domains. The domain of “mood state” was not significantly different between patients with CU and psoriasis. The authors concluded that CU severely impairs HRQL. The HRQL of CU has also been compared against a serious non-skin disease. O’Donnell and colleagues collected CU-specific questionnaires and Nottingham health profiles from patients with CU, and compared them to responses from patients with ischemic coronary artery disease awaiting coronary bypass surgery (Citation22). Between these two groups of patients, lack of energy, social isolation and emotional upset were nearly identical, whereas sleep disturbance was greater in patients with CU, and physical mobility and pain were less in patients with CU.

Despite their low CCI indicating a lack of mortality-related medical conditions, patients with CU had frequent healthcare visits, and an average of 0.4 ER visits and 0.3 hospitalizations in the previous six months. It is likely that some of these visits were for concomitant conditions. For example, the frequency of ER visits in patients with CU may be reflective of visits for angioedema episodes that occur in approximately one-third to two-thirds of patients with certain types of CU, including CIU (Citation2). Furthermore, visits to psychiatrists and psychologists/psychotherapists were numerically higher in patients with CU compared to patients with psoriasis, which is consistent with the increased anxiety, depression, and sleep problems reported in patients with CU. In a survey of 100 patients with CIU (defined as chronic spontaneous urticaria), nearly half were found to have at least one mental disorder, such as anxiety disorders, depressive disorders, hypochondria and obsessive compulsive disorder (Citation23). The presence of such mental disorders may also have played a role in the frequent healthcare visits observed in the current analysis in patients with CU compared to patients with psoriasis.

The NHWS is a useful source of information, and has been demonstrated to provide results consistent with other sources (Citation24,Citation25). Although a potential limitation of this survey is that patients could not select the type of CU (i.e. idiopathic versus inducible), the results should be generalizable to CIU given that it is the largest subgroup of CU, accounting for 66%–93% of CU cases (Citation2).

Another potential limitation of this analysis is that concurrent angioedema was unable to be determined. Patients frequently have concomitant CU and angioedema and it is possible that angioedema could have had an impact on the burden of illness. However, in a study of patients with various types of urticarial conditions, subgroup analysis of DLQI results found that angioedema did not confer any additional disability compared to CIU alone (Citation26). Similarly, in a questionnaire-based study, the presence or absence of angioedema did not have a significant impact on the impaired quality of life observed with CU compared with matched healthy controls (Citation27).

An additional limitation of this analysis is that the outcomes measured may depend upon whether symptoms were experienced in the past or at the time of the survey. The symptoms associated with CU occur spontaneously and may not be continuous. Since the recall periods of some of the outcomes measured (work and activity impairment) for both CU and psoriasis patients were as short as the prior seven days, whereas some of the other outcomes (e.g. psychological complaints) were for the prior 12 months, not all of the outcomes may have been experienced at the time of the survey and might be underestimated. Likewise, the measure of severity in psoriasis was via self-report, which may differ from clinical measures of severity; the severity of CU was not collected.

Compared with better characterized dermatologic conditions such as psoriasis, the burden of CU may be less acknowledged by physicians and payers. However, the results of this analysis indicate that CU can have a notable detrimental impact on a patient’s daily life, and better management is needed. Given that up to 60% of patients do not respond adequately to first-line treatment (Citation4), add-on therapies may need to be implemented in these patients. The ASSURE-CSU study assessing burden of CIU in patients with inadequate control with first-line therapy provide additional and some deeper insights into this patient population with high, under-recognized, unmet need (Citation28).

Conclusions

Patients with CU indicated mental health impairment to a similar level as moderate and severe psoriasis, and physical impairment similar to moderate psoriasis. Work and non-work activity levels were between those of moderate and severe psoriasis. High levels of depression, anxiety, and overall healthcare use among CU patients suggest a need for better management of patients with this disease. Given CIU accounts for the vast majority of patients with CU, this analysis should also reflect the burden of illness seen in patients with CIU. Additional research specifically in patients with CIU should be considered.

Geolocation information

This research is specific to the United States.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by Novartis Pharmaceutical Corporation and Genentech, Inc. Prakash Navaratnam and Howard Friedman of DataMed Solutions, LLC, provided statistical and analytical assistance for the project, and reviewed the manuscript. This assistance was funded by Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation and Genentech, Inc. Medical writing and editorial assistance was provided by Erin P. Scott, PhD of Scott Medical Communications, LLC. This assistance was funded by Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation and Genentech, Inc.

Disclosure statement

Susan Gabriel, Meryl H. Mendelson and Haijun Tian are employees of Novartis Pharmaceutical Corporation. Jonathan A. Bernstein is a primary investigator for Novartis and Genentech, Dyax, Shire, CSL Behring and Biocryst, is a speaker for Novartis and Genentech, Dyax, Shire, Greer, Baxalta and CSL Behring, and is a consultant for Dyax, Shire and CSL Behring. Maria-Magdalena Balp is an employee of Novartis Pharma AG. Jeffrey Vietri is an employee of Kantar Health, which received fees from Novartis for data access and analysis. Mark Lebwohl is an employee of the Mount Sinai Medical Center which receives research funds from AbGenomics, Amgen, Anacor, Boehringer Ingleheim, Celgene, Ferndale, Lilly, Janssen Biotech, Kadmon, LEO Pharmaceuticals, Medimmune, Novartis, Pfizer, Sun Pharmaceuticals and Valeant.

References

- Zuberbier T, Aberer W, Asero R, et al. The EAACI/GA(2) LEN/EDF/WAO Guideline for the definition, classification, diagnosis, and management of urticaria: the 2013 revision and update. Allergy. 2014;69:868–87.

- Maurer M, Weller K, Bindslev-Jensen C, et al. Unmet clinical needs in chronic spontaneous urticaria. A GA(2)LEN task force report. Allergy. 2011;66:317–30.

- Bernstein JA, Lang DM, Khan DA, et al. The diagnosis and management of acute and chronic urticaria: 2014 update. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133:1270–7.

- Kaplan AP. Treatment of chronic spontaneous urticaria. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2012;4:326–31.

- Barbosa F, Freitas J, Barbosa A. Chronic idiopathic urticaria and anxiety symptoms. J Health Psychol. 2011;16:1038–47.

- Engin B, Uguz F, Yilmaz E, et al. The levels of depression, anxiety and quality of life in patients with chronic idiopathic urticaria. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:36–40.

- Toubi E, Kessel A, Avshovich N, et al. Clinical and laboratory parameters in predicting chronic urticaria duration: a prospective study of 139 patients. Allergy. 2004;59:869–73.

- Vietri J, Turner SJ, Tian H, et al. Effect of chronic urticaria on US patients: analysis of the National Health and Wellness Survey. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2015;115:306–11.

- Balp MM, Vietri J, Tian H, Isherwood G. The impact of chronic urticaria from the patient's perspective: a survey in five European countries. Patient. 2015;8:551–8.

- Cohen BE, Martires KJ, Ho RS. Psoriasis and the risk of depression in the US population: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2009–2012. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:73–9.

- Van Voorhees AS, Fried R. Depression and quality of life in psoriasis. Postgrad Med. 2009;121:154–61.

- Wahl A, Loge JH, Wiklund I, Hanestad BR. The burden of psoriasis: a study concerning health-related quality of life among Norwegian adult patients with psoriasis compared with general population norms. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:803–8.

- The National Health and Wellness Survey Fact Sheet. 2015. Available from http://www.kantarhealth.com/docs/datasheets/Kantar_Health_NHWS_datasheet%20.pdf. Accessed January 13 2016.

- About Psoriasis 2016. Available from https://www.psoriasis.org/about-psoriasis. Accessed February 10 2016.

- Ware J, Kosinski M, Turner-Bowker D, Gandek B. How to Score Version 2 of the SF-12 Health Survey. Lincoln: QualityMetric, Inc., 2002.

- Maruish M, ed. User's Manual for the SF-36v2 Health Survey, 3rd ed. Lincoln: QualityMetric, Inc., 2011.

- Brazier JE, Roberts J. The estimation of a preference-based measure of health from the SF-12. Med Care. 2004;42:851–9.

- Reilly MC, Zbrozek AS, Dukes EM. The validity and reproducibility of a work productivity and activity impairment instrument. Pharmacoeconomics. 1993;4:353.

- Broder MS, Raimundo K, Antonova E, Chang E. Resource use and costs in an insured population of patients with chronic idiopathic/spontaneous urticaria. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2015;16:313–21.

- Zuberbier T, Balke M, Worm M, et al. Epidemiology of urticaria: a representative cross-sectional population survey. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2010;35:869–73.

- Grob JJ, Revuz J, Ortonne JP, et al. Comparative study of the impact of chronic urticaria, psoriasis and atopic dermatitis on the quality of life. Br J Dermatol. 2005;152:289–95.

- O'Donnell BF, Lawlor F, Simpson J, et al. The impact of chronic urticaria on the quality of life. Br J Dermatol. 1997;136:197–201.

- Staubach P, Dechene M, Metz M, et al. High prevalence of mental disorders and emotional distress in patients with chronic spontaneous urticaria. Acta Derm Venereol. 2011;91:557–61.

- Bolge SC, Doan JF, Kannan H, Baran RW. Association of insomnia with quality of life, work productivity, and activity impairment. Qual Life Res. 2009;18:415–22.

- Liu GG, DiBonaventura M, Yuan Y, et al. The burden of illness for patients with viral hepatitis C: evidence from a national survey in Japan. Value Health. 2012;15:S65–S71.

- Poon E, Seed PT, Greaves MW, Kobza-Black A. The extent and nature of disability in different urticarial conditions. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140:667–71.

- Staubach P, Eckhardt-Henn A, Dechene M, et al. Quality of life in patients with chronic urticaria is differentially impaired and determined by psychiatric comorbidity. Br J Dermatol. 2006;154:294–8.

- Weller K, Maurer M, Grattan C, et al. ASSURE-CSU: a real-world study of burden of disease in patients with symptomatic chronic spontaneous urticaria. Clin Transl Allergy. 2015;5:29.