Abstract

Objectives: This retrospective analysis of the IMS PharMetrics Plus claims database aimed to describe the current real-world treatment patterns for metastatic melanoma in the USA.

Methods: Included patients (aged ≥18 years) had ≥1 prescription for ipilimumab, vemurafenib, temozolomide or dacarbazine between 1 January 2011 and 31 August 2013; diagnosis of melanoma and metastasis before first use (index date); no index drug use prior to the index date; continuous health plan enrollment for ≥6 months before and ≥3 months after index date. Proportion of days covered (PDC) was defined as days exposed to index therapy divided by continuously enrolled days between index date and last prescription date.

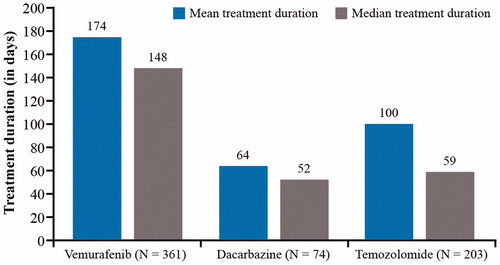

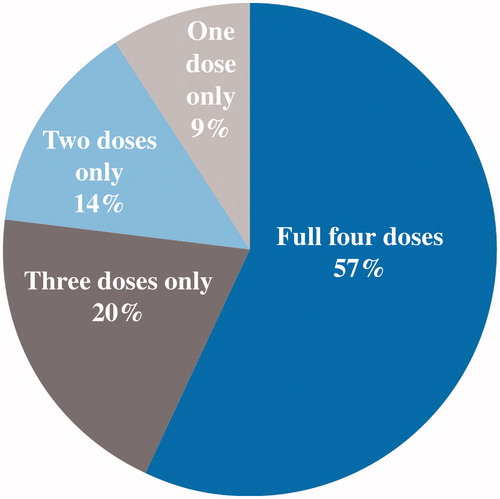

Results: Overall, 1043 patients were included (median age 57 years, 63% male), of whom 39% received the index drug ipilimumab, 35% vemurafenib, 19% temozolomide and 7% dacarbazine. Mean treatment duration (days) was 174 (vemurafenib), 100 (temozolomide) and 64 (dacarbazine). Mean PDC was 81% (vemurafenib), 67% (temozolomide) and 51% (dacarbazine). For patients receiving ipilimumab, 58% had the full 4 doses, 20% 3 doses, 14% 2 doses and 9% 1 dose only for the first induction course; 4% received re-induction, and none had a second re-induction.

Conclusions: This study provides insights into the treatment patterns for metastatic melanoma, including newer agents, in real-world clinical practice.

Introduction

Melanoma is a rare but serious skin cancer that can rapidly infiltrate deep, vascular skin layers and frequently metastasizes (Citation1,Citation2). Melanoma represents only a small proportion of all skin cancer cases (<5%) (Citation3), but is responsible for approximately 90% of skin cancer-related deaths (Citation4). Although melanoma affects people of all ages, 34% of patients are younger than 55 years old at diagnosis (Citation5). Metastatic melanoma is associated with significantly reduced functional well-being for patients (Citation6) and substantial productivity losses due to mortality (Citation7).

Overall, more years of life per patient are lost to melanoma than to many other cancers, and patients with metastatic melanoma die an average of 20 years prematurely (Citation7,Citation8). Melanoma was expected to cause an estimated 9940 deaths in the US in 2015; between 2007 and 2011, annual death rates due to melanoma decreased by 2.6% in the <50-year age group but increased by 0.6% in the ≥50-year age group (Citation3). Historically, the 5-year survival rate for patients with regional metastases (stage III disease) ranges from 40% to 78%, depending on stage (IIIA, IIIB, IIIC), and prognosis for patients with distant metastases (stage IV melanoma) remains poor, with 1-year survival rates ranging from 33% to 62%, depending on sub-stage (Citation9).

For melanomas detected at an early stage (no lymph node involvement), surgical excision often provides the definitive and usually curative therapy (Citation3,Citation10), but additional treatment for metastatic melanoma may include radiation and systemic therapy (Citation11). For stage III in transit melanoma, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) recommendations for primary treatment include (among others) clinical trial entry, surgical excision, intra-lesional injection such as talimogene laherparepvec, radiation therapy (for unresectable disease) and systemic therapy; followed by observation or adjuvant treatment with interferon alfa (for surgically removed disease) or clinical trial entry. For metastatic or unresectable disease, first-line treatment recommendations now include newer therapies such as immunotherapy or targeted therapy if BRAF is mutated, or clinical trial (Citation10).

Rates of response to older chemotherapy agents such as temozolomide and dacarbazine range from <5% to 15% (Citation11,Citation12), and these agents have not been shown to prolong the overall survival of patients with metastatic melanoma (Citation11,Citation13). Promise has been shown, however, by the immunotherapy ipilimumab in patients with metastatic melanoma. Ipilimumab, an antibody directed against cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 (CTLA-4), is thought to act by inhibiting T-cell inactivation, thus allowing expansion of naturally occurring, melanoma-specific cytotoxic T-cells. Ipilimumab was approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2011 (14) and has shown a survival benefit over conventional therapies (Citation14,Citation15). Prolonged survival (overall and/or progression-free) has been observed in patients with BRAF mutations (which occur in 40–50% of cutaneous melanomas) who received treatment with a BRAF inhibitor (vemurafenib (Citation16), the first BRAF inhibitor to be approved by the FDA in 2011 (Citation17), or dabrafenib (Citation18), approved in 2013 (Citation19)). Recent approvals include pembrolizumab and nivolumab (2014), and talimogene laherparepvec (2015), which were not included in this study.

Although a large amount of clinical trial data on these agents is available; since the approval of the earliest newer agents in 2011, there have been few published real-world studies examining to which extent these treatments were used in patients with metastatic melanoma. The objective of the present study was to describe real-world treatment patterns in patients with metastatic melanoma in the US.

Materials and methods

Study design and patient population

A retrospective cohort analysis was conducted using the IMS PharMetrics Plus Health Plan Claims Database. This database comprises adjudicated claims for more than 150 million unique patients across the USA, with approximately 40 million active in the most recent calendar year and covering both pharmacy and medical claims. Data are available from 2006 onwards, with a typical lag of 3–4 months due to claims adjudication. PharMetrics Plus data include diverse representations of geography, employers, payers, providers and therapy areas, with data from 90% of US hospitals, and over 90% of all US doctors (Citation20).

This study is based on Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA)-compliant data retrieved from the PharMetrics Plus claims database; no ethical approval was required for this retrospective analysis.

During the time frame of the study, new agents (ipilimumab and vemurafenib) and old agents (dacarbazine and temozolomide) were commercially available in the USA.

Patients eligible for inclusion were aged ≥18 years on the index date (the date of the first prescription claim of therapy of interest) and had:

At least one prescription claim with a drug code (National Drug Code [NDC], Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System [HCPCS],) for ipilimumab, vemurafenib, dacarbazine or temozolomide between 1 January 2011 and 31 August 2013,

At least one claim with a diagnosis of melanoma (International Classification of Diseases (9th Revision), Clinical Modification [ICD-9-CM] 172.xx, V10.82) on or before the index date,

At least one claim with a diagnosis of metastasis (ICD-9-CM: 196.xx-198.xx) on or before the index date,

No use of the index drug at any time prior to the index date,

No other primary cancer diagnoses 6 months prior to the index date,

Continuous health plan enrollment ≥6 months before and ≥3 months after the index date,

No missing demographic or health plan information.

Study outcomes

Treatment duration was measured for vemurafenib, dacarbazine and temozolomide from the index date until a gap in supply of >90 days or until the end of follow-up, whichever came first. A new therapy (after discontinuing a therapy) could be included in the study as well, if the new therapy was one of the four drugs of interest and it was the first time that the patient received the therapy. Adherence to index therapy with vemurafenib, dacarbazine or temozolomide was measured by the proportion of days covered (PDC), which was defined as the number of days exposed to index therapy divided by the number of days in the observation period.

Given the unique fixed course of treatment for ipilimumab (administered every 3 weeks for a total of four doses (Citation14)), the number of doses and treatment courses were calculated for this drug.

Statistical analysis

All analyses are descriptive. Mean, standard deviation (SD) and median were calculated for continuous variables, while percentages were calculated for categorical variables. Treatment patterns, including duration of treatment of vemurafenib, dacarbazine and temozolomide and percentages of doses of ipilimumab, are presented descriptively. All data were analyzed using SAS® V9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, US).

Results

A total of 1043 patients with metastatic melanoma were included in the analysis. Of them, 405 (39%) received ipilimumab at index, whereas 361 (35%) received vemurafenib, 74 (7%) received dacarbazine and 203 (19%) received temozolomide.

Patients’ demographic characteristics according to the treatment group are shown in . The mean age was 56 (12) years; 57% of patients were older than 55 years, and 63% were male. Reflecting the commercial nature of the health plan database used for this analysis, 98% the patients were commercial or self-insured at the time of therapy.

Table 1. Baseline demographic characteristics.

shows the patients’ baseline clinical characteristics. The most common sites (not mutually exclusive) of metastasis were the lung (42%), brain (34%), liver (28%) or bone (24%). During the 6-month pre-index period, most patients (97%) had a Charlson Comorbidity Index ([CCI], excluding cancer) score ≥6; hypertension was the most frequently observed comorbid condition (43%, ).

Table 2. Baseline clinical characteristics.

Treatment duration tended to be longer for the newer agents than for the older agents; for the therapies with continuous dosing schedules, the mean (median) treatment durations were 174 (148) days with vemurafenib, 64 (52) days with dacarbazine and 100 (59) days with temozolomide ().

With regard to treatment adherence, the mean PDC was 81% for vemurafenib, 51% for dacarbazine and 67% for temozolomide.

shows the distribution of the treatment doses for ipilimumab, which reflects the unique dosing characteristics of this drug (Citation14). Of patients receiving ipilimumab, 58% (234/405) had the full four doses, 20% (79/405) had only three doses, 14% (57/405) had only two doses and 9% (35/405) had only one dose in the first treatment course; 4% (10/234) received re-treatment, and no patient had a second re-treatment.

Discussion

This study aimed to evaluate patterns of treatments for metastatic melanoma in the US. Of the therapies evaluated, the two newer agents ipilimumab and vemurafenib were the most frequently used, indicating rapid adoption of these treatments by prescribers. In addition, treatment duration was longer for newer agents such as vemurafenib than for the older agents.

Although a study by Toy et al. (Citation21) focused mainly on treatment costs and resource utilization, it reported limited information on treatment patterns in patients with metastatic melanoma. Toy et al. (Citation21), using a slightly earlier database (spanning from 2010 to 2012), reported the frequency of patients receiving therapy in 834 patients with metastatic melanoma: ipilimumab and vemurafenib were the most frequently used agents (265 [32%] ipilimumab, 234 [28%] vemurafenib). Other therapies evaluated were paclitaxel (used by 174 patients), interleukin-2 (104 patients), dacarbazine (46 patients) and temozolomide (11 patients) (Citation21). In the population examined in the current study, temozolomide is more commonly used (19%) than in Toy et al., although both uses were lower than that reported in an earlier study of melanoma treatment patterns between 2005 and 2010, which found that 49% of patients received temozolomide (Citation22).

Patients receiving vemurafenib were slightly younger than those receiving ipilimumab, in agreement with the findings from Toy et al. (Citation21). The current study reported longer treatment duration for vemurafenib (mean: 174 days) than that reported in Toy et al. (mean: 112 days), which may reflect a longer available follow-up time since the regulatory approval of vemurafenib (August 2011). Treatment duration for dacarbazine was similar in the current study (64 days) compared with that reported in Toy et al. (69 days), while temozolomide treatment duration was longer in the current study (100 days) than in Toy et al. (33 days). Toy et al. reported a mean treatment time of 50 days for patients receiving ipilimumab; however, this may not be an appropriate measure, considering its unique fixed dosing schedule.

Of the patients receiving ipilimumab, 58% received all four doses; this was slightly lower than that of the population from the ipilimumab pivotal Phase III clinical trial, in which 64% of patients received all four doses of ipilimumab (Citation15). In addition, 4% received re-treatment, similar to the Phase III trial in which 5.9% of patients received re-treatment, 1% had a second re-treatment and 0.1% had a third re-treatment course (Citation23). Data from an expanded access program in Italy showed that 6% of patients received re-treatment (Citation24).

In a clinical trial of vemurafenib (Citation25), the median duration of treatment was 4.2 months for vemurafenib and 0.8 months for dacarbazine. Therefore, the real-world evidence of treatment duration for vemurafenib and dacarbazine (median: 148 days and 52 days, respectively) in the current study was longer than that in the vemurafenib clinical trial (median: 126 days and 24 days, respectively). Treatment duration for temozolomide has not been found in clinical trials. This study provided evidence on temozolomide treatment duration in real-world clinical practice.

There are some limitations to the study. Claims data are collected for billing and reimbursement rather than research purposes, thus assumptions were made when interpreting the prescription data. A cancer diagnosis can be found as an ICD-9 diagnosis code in the data but no information on stage or histology is included in the claims data. The results are based on a minimum of 3-month follow-up period and may differ with a longer observation period. The treatment landscape is evolving rapidly, and newer therapies approved (dabrafenib, trametinib, nivolumab, pembrolizumab and talimogene laherparepvec) were not available for inclusion in the database. There is a need to update this analysis to include agents that have been approved since 2013 once longer follow-up data become available. Additionally, the current study did not examine line of therapy and factors potentially associated with treatment duration, which were outside of the scope of the study. However, these topics should be examined in the future once longer-term follow-up data and a larger sample size become available. Finally, data within the PharMetrics Plus database are weighted toward a commercially insured population; therefore these findings may be less generalizable to patients with other payer types (i.e., Medicare or self-pay), or uninsured individuals.

As limited data is available on the patterns of treatment for metastatic melanoma since the introduction of newer agents, this study provides insights into the treatment patterns up to 2013 using newer and older agents to treat metastatic melanoma in real-world clinical practice. Further observational studies are warranted to examine these patterns after the recent approvals of immunotherapies and oncolytic viral therapy are added to the current guidelines and used in clinical practice of melanoma treatment.

Acknowledgements

Sponsorship for this study and article processing charges were funded by Amgen Inc. Medical writing support was provided by ApotheCom Ltd, funded by Amgen Inc. All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this manuscript, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given final approval to the version to be published.

Disclosure statement

This research was funded by Amgen Inc. Qiufei Ma, Nicolas Batty, Beth Barber and Zhongyun Zhao are employees of Amgen Inc. and hold stocks of Amgen. Dionne Hines and Julie Munakata are employees of IMS Health and hold stocks of IMS Health. Yaozhu Juliette Chen was an employee of IMS Health when this study was conducted.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Meier F, Nesbit M, Hsu MY, et al. Human melanoma progression in skin reconstructs: biological significance of bFGF. Am J Pathol. 2000;156:193–200.

- Tas F. Metastatic behavior in melanoma: timing, pattern, survival, and influencing factors. J Oncol. 2012;2012:647684. doi:10.1155/2012/647684.

- American Cancer Society [Internet]. Cancer Facts & Figures. US: American Cancer Society; 2015 [cited 2016 Aug 16]. Available from: http://www.cancer.org/acs/groups/content/@editorial/documents/document/acspc-044552.pdf.

- Garbe C, Peris K, Hauschild A, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of melanoma: European consensus-based interdisciplinary guideline. Eur J Cancer. 2010;46:270–83.

- International Agency for Research on Cancer [Internet]. Globocan. France: IARC; 2015 [cited 2016 Aug 16]. Available from: http://globocan.iarc.fr/Default.aspx.

- Barbato MT, Bakos L, Bakos RM, et al. Predictors of quality of life in patients with skin melanoma at the dermatology department of the Porto Alegre Teaching Hospital. An Bras Dermatol. 2011;86:249–56.

- Ekwueme DU, Guy GP Jr, Li C, et al. The health burden and economic costs of cutaneous melanoma mortality by race/ethnicity-United States, 2000 to 2006. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:S133–S43.

- Thiam A, Zhao Z, Quinn C, Barber B. Years of life lost due to metastatic melanoma in 12 countries. J Med Econ. 2016;19:1–6.

- Balch CM, Gershenwald JE, Soong SJ, et al. Final version of 2009 AJCC melanoma staging and classification. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:6199–206.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network [Internet]. NCCN Clinical Guidelines in Oncology. Melanoma. USA: NCCN; 2016 [cited 2016 Aug 16]. Available from: http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/f_guidelines.asp.

- Bhatia S, Tykodi SS, Thompson JA. Treatment of metastatic melanoma: an overview [review]. Oncology (Williston Park, N.Y.). 2009;23:488–96.

- Lui P, Cashin R, Machado M, et al. Treatments for metastatic melanoma: synthesis of evidence from randomized trials [review]. Cancer Treat Rev. 2007;33:665–80.

- Serrone L, Zeuli M, Sega FM, Cognetti F. Dacarbazine-based chemotherapy for metastatic melanoma: thirty-year experience overview. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2000;19:21–34.

- Bristol-Myers Squibb [Internet]. Yervoy prescribing information. USA: Bristol-Myer Squibb; 2011 [cited 2016 Aug 16]. Available from: http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2011/125377s0000lbl.pdf.

- Hodi FS, O'Day SJ, McDermott DF, et al. Improved survival with ipilimumab in patients with metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:711–23.

- Chapman PB, Hauschild A, Robert C, et al. Improved survival with vemurafenib in melanoma with BRAF V600E mutation. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2507–16.

- Genentech [Internet]. Zelboraf Prescribing Information. USA: Genentech; 2015 [cited 2016 Aug 16]. Available from: http://www.gene.com/download/pdf/zelboraf_prescribing.pdf.

- Hauschild A, Grob JJ, Demidov LV, et al. Dabrafenib in BRAF-mutated metastatic melanoma: a multicentre, open-label, phase 3 randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2012;380:358–65.

- GlaxoSmithKline [Internet]. Tafinlar Prescribing Information. USA: Novartis; 2015 [cited 2016 Aug 16]. Available from: http://www.pharma.us.novartis.com/product/pi/pdf/tafinlar.pdf.

- IMS Health [Internet]. PharMetrics Plus Data Dictionary. USA: IMS Health; 2013. [cited 2016 Aug 16]. Available from: http://tri.uams.edu/files/2015/08/Pharmetrics-Plus-Data-Dictionary-Jan-2013.pdf.

- Toy EL, Vekeman F, Lewis MC, et al. Costs, resource utilization, and treatment patterns for patients with metastatic melanoma in a commercially insured setting. Curr Med Res Opin. 2015;31:1561–72.

- Zhao Z, Wang S, Barber BL. Treatment patterns in patients with metastatic melanoma: a retrospective analysis. J Skin Cancer. 2014;2014:371326. doi:10.1155/2014/371326.

- Hodi FS, O'Day SJ, McDermott DF, et al. Re-induction with ipilimumab, gp100 peptide vaccine, or a combination of both from a phase III, randomized, double-blind, multicenter study of previously treated patients with unresectable stage III or IV melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:15_suppl 8509.

- Chiarion-Sileni V, Pigozzo J, Ascierto PA, et al. Ipilimumab retreatment in patients with pretreated advanced melanoma: the expanded access programme in Italy. Br J Cancer. 2014;110:1721–26.

- Sosman JA, Kim KB, Schuchter L, et al. Survival in BRAF V600-mutant advanced melanoma treated with vemurafenib. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:707–14.