Abstract

Background: Rosacea treatment success is usually defined as a score of 1 (‘almost clear’) or 0 (‘clear’) on the 5-point Investigator Global Assessment (IGA) scale.

Objective: To evaluate whether, after successful treatment, ‘clear’ subjects had better outcomes than ‘almost clear’ subjects.

Methods: A pooled analysis was performed on 1366 rosacea subjects from four randomized controlled trials with IGA before and after treatment (ivermectin, metronidazole or vehicle). Assessments included the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) questionnaire and subject assessment of rosacea improvement. In one trial, patients were followed after the treatment period to measure time to relapse (IGA score ≥2).

Results: At end of treatment, more ‘clear’ than ‘almost clear’ subjects had a clinically meaningful difference in DLQI (59% vs. 44%; p < .001) and a final DLQI score of 0–1 indicating no effect on quality of life (84% vs. 66%; p < .001). More ‘clear’ subjects reported an ‘excellent’ improvement in their rosacea (77% vs. 42%; p < .001). The median time to relapse was more than 8 months for ‘clear’ vs. 3 months for ‘almost clear’ subjects (p < .0001).

Conclusions: Achieving an endpoint of ‘clear’ (IGA 0) vs. ‘almost clear’ (IGA 1) is associated with multiple positive patient outcomes, including delayed time to relapse.

Introduction

Rosacea is a chronic inflammatory skin disease characterized by a number of different symptoms, including inflammatory papules and pustules (lesions) and transient or persistent erythema (Citation1). The pathophysiology of rosacea, although not fully understood, appears to be multifactorial, involving an augmented immune response and neuroimmune/neurovascular dysregulation (Citation2). Demodex folliculorum mites are frequently found in elevated counts in skin surface biopsies of patients with papulopustular rosacea (Citation3–5). Other possible triggers include UV exposure, temperature change, stress, spicy or hot foods and heavy exercise (Citation6). Although rosacea is often considered as a relatively benign disease, it has a significant impact on quality of life since the various signs and symptoms are readily visible on the face and may cause physical discomfort, for example, painful stinging and burning (Citation7–9).

Recent publications describing objectives for rosacea treatments focus mainly on controlling the disorder by delaying or preventing progression, minimizing the discomfort and alleviating symptoms, improving appearance, and sustaining remission with prolonged therapy, as well as lifestyle modification to avoid triggers (Citation10,Citation11). Treatment goals in rosacea should be based on perceived severity and psychosocial burden to achieve patient satisfaction by treating individual features, regardless of severity (Citation12). Current recommendations, in addition to patient education aimed at improving general skin care and the avoidance of triggers, include achieving clear/almost clear skin and improving patient-reported outcomes (visible and non-visible) (Citation12). In recent years, regulatory authorities and payers have commonly used an Investigator Global Assessment (IGA) final score of 1 (‘almost clear’) or 0 (‘clear’) to define ‘success’ after treatment for rosacea with inflammatory lesions. The IGA is a composite 5-grade score widely used in clinical trials for rosacea, which includes the evaluation of reduction in erythema as well as reduction in inflammatory lesions ().

Table 1. Investigator global assessment (IGA) scale.

The objective of this pooled analysis was to compare the groups of ‘clear’ and ‘almost clear’ subjects at the end of treatment period, whatever their rosacea severity at baseline and irrespective of treatment received, to evaluate differences in patient-reported outcomes (e.g. quality of life [QoL] and subject-assessed improvement in their rosacea) and time to relapse after achievement of treatment success.

Methods

Studies analyzed

This pooled analysis of published and unpublished data aimed to summarize the evidence from four previous Galderma-sponsored studies evaluating the use of ivermectin 1% cream (IVM; Soolantra®, Galderma) in the treatment of inflammatory papules and pustules of rosacea. In a previously unpublished, phase-2, dose-ranging study, 296 subjects with papulopustular rosacea and at least 15 inflammatory lesions as well as at least mild erythema were randomized to receive treatment (IVM or metronidazole [MTZ]) or vehicle for 12 weeks (Study A, data on file). In two phase-3 pivotal studies, 683 and 688 subjects with moderate or severe rosacea (IGA ≥ 3) and 15–70 facial inflammatory lesions were randomized to receive 12 weeks of IVM 1% cream once daily (QD) or vehicle (Studies B and C) (Citation13). In a phase-3 study, 962 subjects with moderate to severe rosacea (IGA ≥ 3) and 15–70 facial inflammatory lesions were randomized to receive IVM 1% cream QD or MTZ 0.75% cream twice daily (BID) for 16 weeks (Study D) (Citation14), followed by a 36-week extension period in successfully treated subjects (IGA 1 or 0) (Citation15) ().

Table 2. Demographic and clinical characteristics of subjects (intent-to-treat) included in the pooled analysis.

Efficacy assessments

For all studies, inflammatory papulopustular rosacea severity had been assessed before and after treatment by Investigator Global Assessment (IGA) () and inflammatory lesion count.

Patient-reported outcomes

At the end of the treatment period, patient-reported outcomes were assessed on pooled data from all treatment groups using the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) (Citation16) and subject assessment of rosacea improvement on a 4-point scale from ‘no improvement’ to ‘excellent improvement’.

The 10 DLQI questions had four possible responses from not at all (0) to very much (3) and the total score was calculated by summing the score of each question; the maximum score is 30 (extremely large effect on patient’s life) and minimum is 0 (no effect on patient’s life) (Citation16). The 10 questions cover six domains and DLQI subscale scores were calculated for symptoms and feelings, daily activities, leisure, work and school, personal relationships and treatment.

Time to relapse

Relapse times of ‘clear’ vs. ‘almost clear’ subjects were assessed from one trial by pooling data from both treatment groups (IVM and MTZ). At the end of a 16-week treatment period, the study treatment was discontinued and patients considered as being successfully treated (IGA 0 or IGA 1) were followed every 4 weeks for up to 36 additional weeks (252 days) to measure time to relapse, which was defined as an IGA score ≥2 (‘mild’) (Citation15). Subjects were assessed for relapse at each 4-weekly visit.

Statistical analysis

All pooled ‘clear’ (IGA 0) subjects after the treatment period, whatever the treatment received whether IVM, MTZ or vehicle, were compared with ‘almost clear’ (IGA 1) subjects and analyzed by chi2 or Fisher’s exact test. Differences between groups in terms of percentage reduction in inflammatory lesions from baseline and in the total DLQI score were analyzed using the Wilcoxon rank sum test. The DLQI score was also analyzed in terms of minimal clinically important difference (MCID). A change in DLQI score of at least four points is considered as a MCID that suggests there has been a meaningful change in the patient’s quality of life since the previous DLQI measurement (Citation17). The percentage of subjects with a DLQI MCID at the end of the treatment period in each group was analyzed using the chi2 test.

The difference between groups in terms of median time to relapse (time when 50% of subjects had relapsed) was analyzed using the log-rank test (Kaplan–Meier method).

Analysis was performed using SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

Demographic data

Data were available for a total of 1366 subjects with rosacea and the demographic and baseline characteristics were similar for both groups (). Overall, at baseline, most subjects had moderate rosacea with an IGA score of 3 (79.7%) or severe rosacea with an IGA score of 4 (14.3%). At baseline, the subjects had a mean lesion count of 31.3 lesions, which was almost identical in both groups ().

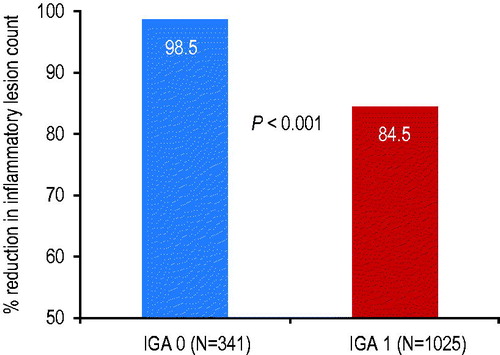

Inflammatory lesion count reduction

Between baseline and the end of the treatment period, the mean percentage reduction in inflammatory lesion count for ‘clear’ subjects was 14% greater compared to ‘almost clear’ subjects (98.5% vs. 84.5% respectively; p < .001) (). The percentage of subjects with 100% reduction in inflammatory lesions at end of treatment was 86.5% vs. 4.9% for the ‘clear’ and ‘almost clear’ subjects, respectively.

Quality-of-life data

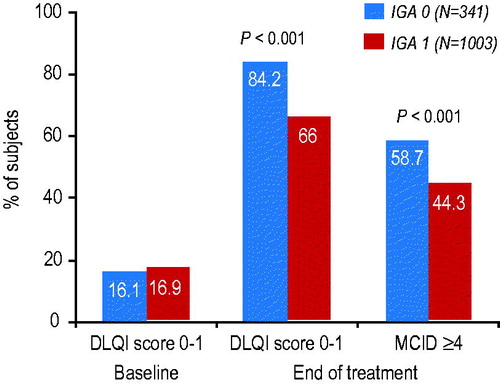

At baseline, the percentages of ‘clear’ and ‘almost clear’ subjects with a total DLQI score of 0–1 indicating no negative effect on quality of life were similar at 16.1% and 16.9%, respectively. At the end of the treatment period, the percentages of subjects with a total DLQI score of 0–1 had increased to 84.2% for ‘clear’ subjects compared to 66.0% for ‘almost clear’ subjects, that is, 18% more ‘clear’ subjects than ‘almost clear’ subjects reported no effect on quality of life at the end of treatment (p < .001) ().

Figure 2. Percentage of ‘clear’ subjects (IGA 0) vs. ‘almost clear’ subjects (IGA 1) with a DLQI score of 0–1 indicating no effect on quality of life at baseline and end of treatment, and a minimal clinically important difference (MCID) in DLQI score between baseline and the end of the treatment period.

The mean change (reduction) in DLQI total score from baseline to end of treatment was 6.1 for ‘clear’ subjects compared to 4.0 for ‘almost clear’ subjects (p < .001). Better mean improvements were observed for the ‘clear’ subjects in all of the six domains covered by the DLQI, especially leisure (1.19 IGA 0 vs. 0.68 IGA 1) and personal relationships (0.89 IGA 0 vs. 0.45 IGA 1) (all p < .001).

Furthermore, more ‘clear’ subjects than ‘almost clear’ subjects (58.7% vs. 44.3%; p < .001) had a clinically meaningful difference (≥4 points) in DLQI from baseline to last visit, which confirms clinically relevant treatment effectiveness ().

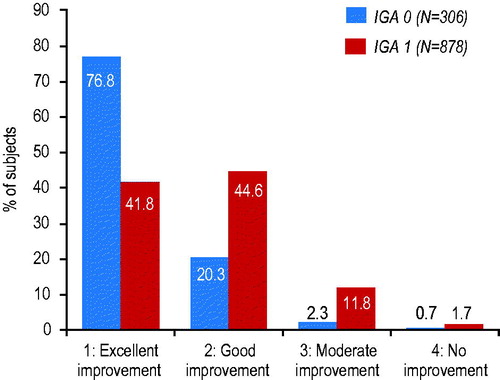

Subject-assessed rosacea improvement data

The improvement in QoL was consistent with the subject-assessed improvement in rosacea severity. At the end of the treatment period, 35% more ‘clear’ subjects than ‘almost clear’ subjects (76.8% vs. 41.8%) reported an ‘excellent’ improvement in their rosacea ().

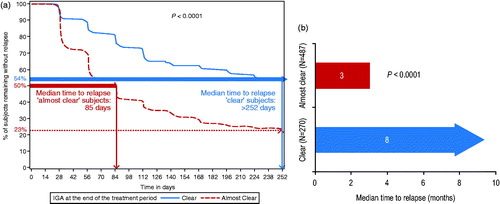

Relapse data

After stopping treatment at the end of the initial 16-week treatment period for ‘clear’ and ‘almost clear’ subjects, median time to relapse to an IGA score of ≥2 (‘mild’) when 50% of subjects had already relapsed was 85 days (i.e. 3 months after stopping treatment) for ‘almost clear’ subjects and was not even reached at the end of the study at 252 days (8 months) for ‘clear’ subjects (p < .0001; ). Hence, the median number of days free of treatment was at least 167 days (more than 5 months) longer for ‘clear’ subjects than ‘almost clear’ subjects.

Figure 4. Time to relapse after stopping treatment at the end of the 16-week treatment period for ‘clear’ subjects (IGA 0) vs. ‘almost clear’ subjects (IGA 1) (p < .0001), as shown by (a) Kaplan–Meier curve and (b) bar chart. The median time to relapse was 85 days (3 months) for ‘almost clear’ subjects and was not reached at 252 days (8 months) for ‘clear’ subjects.

At the end of the study at 252 days (8 months), 54% of ‘clear’ subjects had still not relapsed compared to 23% of ‘almost clear’ subjects, that is, over twice as many ‘clear’ subjects than ‘almost clear’ subjects were still free of treatment 8 months after the initial treatment period ().

Discussion

In interventional studies for inflammatory papules and pustules of rosacea, being ‘almost clear’ on IGA may be defined as success despite falling short of what many patients and doctors consider a fully successful treatment. No previous studies have investigated differences in outcomes between ‘clear’ and ‘almost clear’ subjects and this study addresses whether patients are satisfied when they still have a very few remaining small papules and pustules and/or very mild erythema.

Although the various studies included in this post hoc analysis were different in terms of study design, objective, treatment, duration and rosacea severity, most subjects (80%) had moderate rosacea with a mean number of 31 papules and pustules at baseline. Achieving ‘clear’ (IGA 0) after the respective treatment period was associated with a greater reduction in inflammatory lesions, improved quality of life and subject self-assessment, as well as extended time to relapse.

At end of treatment, ‘clear’ subjects had a 14% higher mean inflammatory lesion count reduction than ‘almost clear’ subjects, which is a difference of more than a noninferiority margin (10%). It is noteworthy that the reduction in lesions for ‘clear’ subjects was not in fact 100% since the IGA is an overall impression but closer, careful inspection may reveal one or two papules or pustules in a small percentage of subjects (and similarly the presence of papules or pustules for a few subjects rated as ‘almost clear’ may not be confirmed on closer examination). At end of treatment, ‘clear’ subjects had a greater improvement in QoL with greater improvements in all six domains of the DLQI, especially improved quality of leisure time and personal relationships. The greater improvement in symptoms for ‘clear’ subjects was confirmed by more ‘clear’ subjects noticing changes in their condition than ‘almost clear’ subjects with 35% more clear subjects reporting an ‘excellent’ improvement in their rosacea (77% vs. 42%, respectively).

The dermatology-specific DLQI has been validated extensively (Citation18). Since the extent of improvement in QoL total scores lack a direct clinical meaning, the concept of MCID was used to describe the smallest change in an outcome that a patient would identify as important (Citation17,Citation19). Between baseline and last visit, one-third more ‘clear’ subjects than ‘almost clear’ subjects (59% vs. 44%) had a clinically meaningful difference (≥4 points) in DLQI score. It might be expected that an even greater difference between ‘clear’ and ‘almost clear’ subjects would be observed in QoL improvement in subjects with severe rosacea at baseline.

As is the case for many dermatological diseases, rosacea is a chronic disease with remissions and exacerbations. Improving treatment options with earlier effective treatment and longer remission times might not only control symptoms, but also delay progression of the disease. Achieving ‘clear’ delayed time to first relapse by more than 5 months compared to ‘almost clear’ subjects, which may contribute to improved quality of life and satisfaction with treatment over the long term. During an 8-month follow-up period after stopping the initial treatment, twice as many ‘clear’ subjects than ‘almost clear’ subjects were still free of treatment (54% vs. 23% respectively). Furthermore, continuing a maintenance treatment after reaching ‘clear’ may be expected to further extend time to relapse.

In this pooled analysis, ‘clear’ vs. ‘almost clear’ subjects were analyzed independently of the treatment (topical IVM, MTZ or vehicle) or the severity of the rosacea at baseline. Currently, FDA approved topical therapies for inflammatory lesions of rosacea include IVM 1% cream QD, MTZ 0.75% cream BID or azelaic acid 15% gel BID (Citation20,Citation21). A combination of systemic oral doxycycline (40 mg modified-release) with topical IVM 1% cream may be required for severe rosacea (Citation22,Citation23). The therapeutic efficacy of MTZ and azelaic acid topical treatments can be attributed to their anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects, whereas IVM has demonstrated activity against Demodex in addition to anti-inflammatory properties (Citation10,Citation13,Citation24,Citation25).

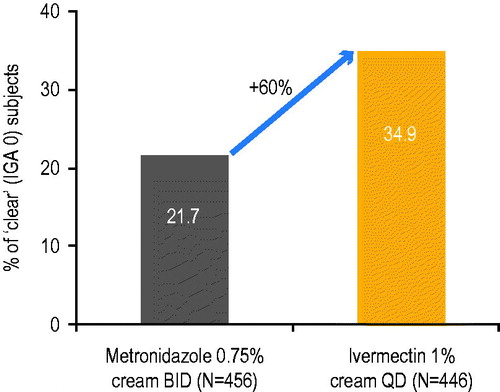

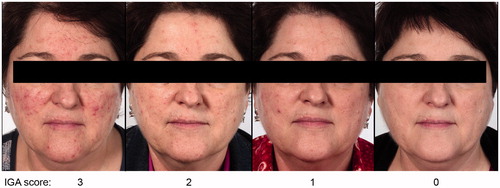

Although all approved treatments have demonstrated efficacy in several randomized-controlled trials, the percentage of ‘clear’ subjects was not usually specified and methodologies differed. Also, many studies were too short to observe the effect of treatment on time to relapse (Citation26,Citation27). In a comparative study of IVM 1% cream QD vs. MTZ 0.75% cream BID in moderate to severe rosacea patients, more subjects reached ‘clear’ with IVM compared to MTZ after 16 weeks treatment (34.9% for IVM vs. 21.7% for MTZ) (Study D (Citation14)) (). Furthermore, in the subpopulation of severe subjects from the same study, over twice as many subjects reached ‘clear’ with IVM 1% cream QD than MTZ 0.75% cream BID (27.5% vs. 12.3%, respectively) (Citation28). The median time to first relapse was also significantly longer for subjects initially treated with IVM 1% cream QD than with MTZ 0.75% cream BID (115 days vs. 85 days, respectively) (Citation15). Representative archive photographs demonstrate a subject who became ‘clear’ (IGA 0) of papules/pustules and erythema after treatment with IVM 1% cream QD monotherapy ().

Figure 5. Percentage of ‘clear’ subjects (IGA 0) after 16 weeks treatment with once-daily ivermectin 1% cream vs. twice-daily metronizadole 0.75% cream.

Figure 6. Representative photographs with the corresponding Investigator Global Assessment (IGA) scores after treatment with once-daily ivermectin 1% cream.

The impact on global success rate, time to relapse, retreatment duration and time free of treatment are also important from a pharmacoeconomic perspective and further studies are warranted to evaluate the overall economic benefit of achieving ‘clear’ vs. ‘almost clear’ (Citation29).

A limitation of this pooled analysis is the limited number of studies. However, the pooled analysis included a large sample size of 1366 subjects and the various analyses consistently showed significant differences between ‘clear’ subjects and ‘almost clear’ subjects. The effectiveness of rosacea treatments on inflammatory lesions and erythema should thus be assessed using a 5-point categorical scale that includes ‘clear’ and ‘almost clear’ (as well as ‘mild’, ‘moderate’ and ‘severe’) as these two grades are of unequivocal clinical relevance. Achieving ‘clear’ on IGA with no papules and pustules and no erythema is clinically meaningful for the patient and easily quantifiable by the investigator.

Conclusions

Subjects achieving an endpoint of ‘clear’ on IGA with no inflammatory papules and pustules and no erythema after treatment of rosacea, however long it takes, have improved quality of life and extended time to relapse compared to ‘almost clear’ subjects.

Acknowledgements

Editorial and medical writing support was provided by Helen Simpson, PhD, of Galderma R&D.

Disclosure statement

GW has been an adviser for Galderma, Allergan, Valeant, Dermira, Cutanea, Aclaris, Alexar, Janssen, SolGel, and Foamix. MS has been an advisory board member for Bayer, Galderma and Marpinion within the past two years and has received lecture fees from AbbVie, Bayer Healthcare, Galderma, and La Roche-Posay. JT has been an advisor, consultant, investigator and/or speaker for Bayer, Cipher, Dermira, Galderma, Roche and Valeant. JMJ has served as an advisor, consultant, speaker and/or investigator for Abbvie, Accuitis, Aclaris, Actelion, Alexar, Amgen, Celgene, Dermira, Galderma, Janssen, Lilly, Medimetriks, Novartis, Pfizer, Promius, and TopMD. NK and GS are full-time employees of Galderma.

References

- Schaller M, Almeida LM, Bewley A, et al. Rosacea treatment update: recommendations from the global ROSacea COnsensus (ROSCO) panel. Br J Dermatol. 2017;176:465–71.

- Del Rosso JQ, Gallo RL, Kircik L, et al. Why is rosacea considered to be an inflammatory disorder? The primary role, clinical relevance, and therapeutic correlations of abnormal innate immune response in rosacea-prone skin. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:694–700.

- Forton F, Germaux MA, Brasseur T, et al. Demodicosis and rosacea: epidemiology and significance in daily dermatologic practice. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:74–87.

- Forton FM, De Maertelaer V. Two consecutive standardized skin surface biopsies: an improved sampling method to evaluate demodex density as a diagnostic tool for Rosacea and Demodicosis. Acta Derm Venereol. 2017;97:242–8.

- Casas C, Paul C, Lahfa M, et al. Quantification of Demodex folliculorum by PCR in rosacea and its relationship to skin innate immune activation. Exp Dermatol. 2012;21:906–10.

- Steinhoff M, Schauber J, Leyden JJ. New insights into rosacea pathophysiology: a review of recent findings. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:S15–26.

- Aksoy B, Altaykan-Hapa A, Egemen D, et al. The impact of rosacea on quality of life: effects of demographic and clinical characteristics and various treatment modalities. Br J Dermatol. 2010;163:719–25.

- Moustafa F, Lewallen RS, Feldman SR. The psychological impact of rosacea and the influence of current management options. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:973–80.

- van der Linden MM, van Rappard DC, Daams JG, et al. Health-related quality of life in patients with cutaneous rosacea: a systematic review. Acta Derm Venereol. 2015;95:395–400.

- Elewski BE, Draelos Z, Dréno B, et al. Rosacea – global diversity and optimized outcome: proposed international consensus from the Rosacea International Expert Group. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25:188–200.

- Weinkle AP, Doktor V, Emer J. Update on the management of rosacea. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2015;8:159–77.

- Tan J, Almeida LM, Bewley A, et al. Updating the diagnosis, classification and assessment of rosacea: recommendations from the global ROSacea COnsensus (ROSCO) panel. Br J Dermatol. 2017;176:431–8.

- Stein L, Kircik L, Fowler J, et al. Efficacy and safety of ivermectin 1% cream in treatment of papulopustular rosacea: results of two randomized, double-blind, vehicle-controlled pivotal studies. J Drugs Dermatol. 2014;13:316–23.

- Taieb A, Ortonne JP, Ruzicka T, Ivermectin Phase III study group, et al. Superiority of ivermectin 1% cream over metronidazole 0·75% cream in treating inflammatory lesions of rosacea: a randomized, investigator-blinded trial. Br J Dermatol. 2015;172:1103–10.

- Taieb A, Khemis A, Ruzicka T, Ivermectin Phase III Study Group, et al. Maintenance of remission following successful treatment of papulopustular rosacea with ivermectin 1% cream vs. metronidazole 0.75% cream: 36-week extension of the ATTRACT randomized study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:829–36.

- Finlay AY, Khan GK. Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI)-a simple practical measure for routine clinical use. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1994;19:210–16.

- Basra MK, Salek MS, Camilleri L, et al. Determining the minimal clinically important difference and responsiveness of the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI): further data. Dermatology (Basel). 2015;230:27–33.

- Basra MK, Fenech R, Gatt RM, et al. The Dermatology Life Quality Index 1994-2007: a comprehensive review of validation data and clinical results. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159:997–1035.

- Jaeschke R, Singer J, Guyatt GH. Measurement of health status. Ascertaining the minimal clinically important difference. Control Clin Trials. 1989;10:407–15.

- van Zuuren EJ, Fedorowicz Z. Interventions for Rosacea. JAMA. 2015;314:2403–4.

- Schaller M, Schöfer H, Homey B, et al. Rosacea management: update on general measures and topical treatment options. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2016;14:17–28.

- Steinhoff M, Vocanson M, Voegel JJ, et al. Topical ivermectin 10 mg/g and oral doxycycline 40 mg modified-release: current evidence on the complementary use of anti-inflammatory Rosacea treatments. Adv Ther. 2016;33:1481–501.

- Schaller M, Schöfer H, Homey B, et al. State of the art: systemic rosacea management. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2016;14 Suppl 6:29–37.

- Layton A, Thiboutot D. Emerging therapies in rosacea. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69(6 Suppl 1):S57–S65.

- Holmes AD, Steinhoff M. Integrative concepts of rosacea pathophysiology, clinical presentation and new therapeutics. Exp Dermatol. 2017. [Epub ahead of print]. doi:10.1111/exd.13143.

- Hopkinson D, Moradi Tuchayi S, Alinia H, et al. Assessment of rosacea severity: a review of evaluation methods used in clinical trials. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:138–43.e4.

- Elewski BE, Fleischer AB Jr, Pariser DM. A comparison of 15% azelaic acid gel and 0.75% metronidazole gel in the topical treatment of papulopustular rosacea: results of a randomized trial. Arch Dermatol. 2003;139:1444–50.

- Schaller M, Dirschka T, Kemény L, et al. Superior efficacy with ivermectin 1% cream compared to metronidazole 0.75% cream contributes to a better quality of life in patients with severe papulopustular rosacea: a subanalysis of the randomized, investigator-blinded ATTRACT study. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2016;6:427–36.

- Taieb A, Stein Gold L, Feldman SR, et al. Cost-effectiveness of ivermectin 1% cream in adults with papulopustular rosacea in the United States. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2016;22:654–65.