Abstract

Background There is a need for safe, effective treatment for atopic dermatitis (AD) in the Middle East.

Objective To propose a practical algorithm for the treatment of AD throughout the Middle East.

Methods An international panel of six experts from the Middle East and one from Europe developed the algorithm. The practical treatment guide was based on a review of published guidelines on AD, an evaluation of relevant literature published up to August 2016 and local treatment practices.

Results Patients with an acute mild-to-moderate disease flare on sensitive body areas should apply the topical calcineurin inhibitor (TCI), pimecrolimus 1% cream twice daily until clearance. For other body locations, a TCI, either pimecrolimus 1% cream, tacrolimus 0.03% ointment in children or 0.1% ointment in adults, should be applied twice daily until clearance. Emollients should be used as needed. Patients experiencing acute severe disease flares should apply a topical corticosteroid (TCS) according to their label for a few days to reduce inflammation. After clinical improvement, pimecrolimus for sensitive skin areas or TCIs for other body locations should be used until there is a complete resolution of lesions.

Conclusions These recommendations are expected to optimize AD management in patients across the Middle East.

Introduction

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a chronic inflammatory, relapsing and pruritic skin disease, which commonly presents during infancy, but can affect patients at any age (Citation1–4). The disease has a multifactorial pathogenesis involving interactions between environmental factors (such as pollution and the microbiome), defects in innate and adaptive immunity and epidermal barrier dysfunction (Citation5–7). AD is often the first manifestation of the atopic march in which allergen penetration into the skin is believed to lead to the subsequent development of allergic rhinitis and asthma (Citation8). Across the Middle East, many patients with AD have atopic co-morbidities. For example, studies have shown that 10.1% of Iranian children with AD have asthma, and 21.5% have allergic rhinitis (Citation9). AD is also associated with other non-atopic co-morbidities such as cardiovascular disease, metabolic diseases, gastrointestinal problems and psychological disorders through underlying long-term systemic inflammation (Citation10,Citation11).

Although AD is a common condition in countries throughout the Middle East, there is a need for a safe, effective treatment as studies show that the prevalence of the disease in this region is rising (Citation12,Citation13). Prevalence estimates vary according to the age of the studied participants and the methods used to identify people suffering from the disease. Studies using the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood questionnaire have reported eczema prevalence rates in adolescents aged 13–14 years of 3.9% in Syria (Citation14), 10.1% in Iran (Citation15), 11.3% in Kuwait (Citation16) and 14.4% in Oman (Citation17). The highest prevalence of AD was recorded in a study of 854 citizens of Taif, Saudi Arabia, where 45.4% of adolescents and adults suffered from the disease (Citation18).

It has also been shown that AD has a substantial negative impact on patients, their families and healthcare systems. For example, studies in countries across the Middle East have demonstrated the strong negative impact AD has on the quality of life (QoL) of patients and their families (Citation19–22). Itching and scratching had the greatest impact on QoL in children with AD, followed by the child’s mood and the time it took for the child to get to sleep (Citation19). In comparison, parents’ QoL was affected by factors such as sleep disturbance, increased monthly expenditure and emotional distress (Citation21,Citation22). The negative impact of AD on QoL increases in both patients and parents as the severity of the disease rises (Citation20–22). Furthermore, AD creates a substantial burden for affected families and healthcare systems due to the direct medical costs and indirect costs resulting from time lost from work (Citation23).

Corticophobia is common across cultures and may impact adherence and treatment outcomes for patients with AD (Citation24). As such, safe and effective alternatives to topical corticosteroids (TCS) and a new therapeutic approach are required for the treatment of AD. This article therefore proposes a practical algorithm for the treatment of patients with AD in daily practice, in countries throughout the Middle East.

Methods

An international panel of six experts from countries across the Middle East and one from Europe was convened to develop a practical algorithm for the treatment of AD patients in the Middle East. The practical treatment guide was developed based on a review of published international and national guidelines on AD (Citation3,Citation25–29) an evaluation of relevant literature published up to August 2016 and local treatment practices.

Practical algorithm for the topical treatment of AD in the Middle east

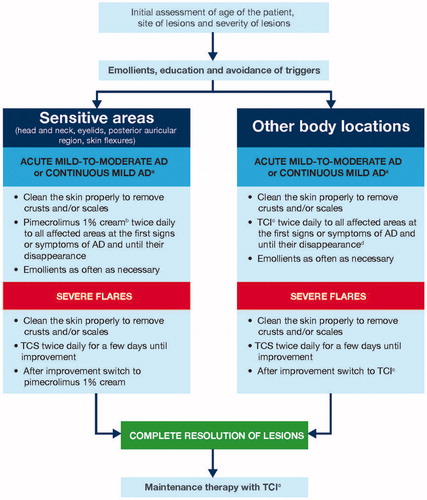

An algorithm for the treatment of AD in children, adolescents and adults from the Middle East is outlined in . In order to assess the severity of a patient’s AD, the Investigator’s Global Assessment (IGA) or the SCORing Atopic Dermatitis (SCORAD) index can be used (Citation30,Citation31). In the first instance, for those patients presenting with AD, it is recommended that the skin is cleaned to remove crusts and/or scales prior to any initial anti-inflammatory therapy. It is further advised that all patients should apply emollients when required and as often as necessary.

Figure 1. Algorithm for the treatment of atopic dermatitis in patients (children, adolescents and adults) from the Middle East. aChildren, adolescents and adults. bIn these areas a cream is better accepted by patients than an ointment. cTCI = Pimecrolimus 1% cream; tacrolimus 0.1% ointment for adults; or tacrolimus 0.03% ointment for children. Pimecrolimus is indicated for mild-to-moderate AD while tacrolimus is indicated for moderate-to-severe cases. dIf inflammation is not controllable with TCIs, brief treatment with TCS may be recommended. AD: atopic dermatitis; TCI: topical calcineurin inhibitor; TCS: topical corticosteroid.

If a patient has an acute mild-to-moderate disease flare on a sensitive body area, we suggest applying a topical calcineurin inhibitor (TCI), in particular pimecrolimus 1% cream twice daily, until the signs and symptoms have resolved. Pimecrolimus is the preferred TCI due to its formulation, favorable tolerability profile, and superior acceptance by patients (see further details below). For other body locations, apply a TCI, either pimecrolimus 1% cream, tacrolimus 0.03% ointment in children or 0.1% ointment in adults, twice daily until the signs and symptoms of AD have resolved. However, in some moderate cases, TCS may be used for a few days before applying a TCI.

In patients experiencing an acute severe disease flare, TCS according to their label should be used for a few days to reduce inflammation. Once there has been a clinical improvement, it is recommended to switch to pimecrolimus for sensitive skin areas or TCIs for other body locations until there is a complete resolution of lesions. Although the signs and symptoms of a patient’s AD may have resolved, it is important they continue to apply TCIs to the previously affected area twice or three times weekly to ensure symptoms do not return. In addition, liberal use of emollients on the entire body is also recommended.

TCI use for sensitive body areas in mild-to-moderate AD flares

The majority of patients suffering from AD in countries from the Middle East have mild-to-moderate AD, rather than a severe form of the disease (Citation12,Citation21). A TCI is therefore recommended in this group of patients. The American Academy of Dermatology (AAD), the European and the German guidelines also favor the use of TCI over TCS for these delicate body areas in the topical long-term management of AD (Citation3,Citation27,Citation32). Evidence from several clinical studies and studies of real-life clinical practice supports the first-line use of pimecrolimus for AD in sensitive skin areas, such as the face, neck, genital area and inguinal folds, where the disease commonly presents (Citation33).

The Petite study was the longest and largest intervention study to be conducted in infants with mild-to-moderate AD. A total of 2418 infants with AD were enrolled in this 5-year study and were randomized to either ‘as needed’ treatment with pimecrolimus 1% cream or low-to-medium potency TCS, in order to compare safety and efficacy (Citation34). The results showed that pimecrolimus was highly effective for the treatment of facial dermatitis with 61% of pimecrolimus-treated infants achieving a facial IGA score of 0 or 1, indicating they were clear or almost clear of disease after only 3 weeks of treatment. At the end of the 5-year study, this increased to 97% (Citation34). This supports the use of pimecrolimus as a first-line treatment of mild-to-moderate AD in sensitive areas in both infants and children.

In a shorter-term clinical study, a significantly greater proportion of adolescents and adults were cleared or almost cleared of facial AD (47% Vs 16%, p < .001) and achieved clearance of eyelid dermatitis (45% Vs 19%, p < .001) after 6 weeks of treatment with pimecrolimus compared with vehicle (Citation35). Similarly, 6 weeks of pimecrolimus treatment in children led to a greater proportion of patients being cleared or almost cleared of facial AD compared with vehicle (75% Vs 51%, p < .001) (Citation36). Furthermore, in a real-life study of 947 AD patients, pimecrolimus was highly effective for the treatment of facial AD when used at the first signs or symptoms of the disease, with over 40% of patients in all age groups with AD of different severities being clear or almost clear of facial AD after 6 months (Citation37).

Other key clinical benefits of pimecrolimus include the rapid and sustained improvements in the overall signs and symptoms of AD (Citation34), including a rapid reduction in pruritus within 48 h of treatment being initiated (Citation38,Citation39), reduction in the progression to disease flares (Citation40–43) and significant improvements in the QoL of both patients and their carers (Citation40,Citation44,Citation45).

Further reasons as to why pimecrolimus should be the treatment of choice for sensitive skin areas is that the cream formulation is easier to apply and rub-in to sensitive areas compared with the greasy ointment formulation of tacrolimus (Citation46). In a comparative study of pimecrolimus 1% cream and tacrolimus 0.03% ointment for 6 weeks in 141 pediatric patients with moderate AD, patients and their caregivers expressed a strong preference for the cream formulation of pimecrolimus () (Citation46). A greater proportion of the patients in the pimecrolimus group considered it to be suitable for use on sensitive skin, easy to apply and rub-in, and that it had a non-sticky feel (Citation46). Patient preference should be taken into account, as it is likely to improve their adherence to treatment.

Table 1. Comparative acceptability of pimecrolimus 1% cream and tacrolimus 0.03% ointment in pediatric patients with moderate atopic dermatitis (Citation46).

Secondly, this study also indicated that pimecrolimus may be more effective than tacrolimus for the treatment of sensitive skin areas as pimecrolimus was associated with a 54% reduction from baseline in the head and neck area that was affected by AD compared to a decrease of 35% with tacrolimus (Citation46). Although these differences between treatment groups were not statistically significant, there was evidence for increased efficacy with pimecrolimus. For instance, pimecrolimus 1% cream had a greater effect on the head and neck region whereas, tacrolimus 0.03% ointment was associated with greater changes on the legs (Citation46). A broader comparison of the efficacy of TCI in a network meta-analysis of 19 studies involving 6413 children with AD, showed that there was no significant difference between pimecrolimus 1% cream and tacrolimus 0.03% or 0.1% ointments in terms of their ability to improve AD and safety profile (Citation47). However, there is some controversy as other studies report superiority of tacrolimus 0.1% (Citation48).

Thirdly, the permeation of pimecrolimus through the skin is lower than that of tacrolimus, as pimecrolimus is 8-fold more lipophilic and has a higher binding affinity for skin proteins (Citation49,Citation50). This is a particularly important consideration for the treatment of sensitive skin areas where the skin is thinner. Systemic exposure following topical application of pimecrolimus 1% cream is minimal (even in patients with extensive disease) and lower than for tacrolimus 0.1% ointment (Citation51,Citation52). In addition, evidence suggests more pronounced immunosuppressive activity with tacrolimus compared with pimecrolimus, with impairment in lymphocyte activation reported following tacrolimus treatment (Citation53).

A common adverse event of TCI is a transient sensation of burning and stinging at the application site. In a comparative study of TCI in pediatric patients, there were fewer and shorter application site reactions with pimecrolimus 1% cream compared with tacrolimus 0.03% ointment (Citation46). After 4 days of treatment, a lower proportion of pimecrolimus versus tacrolimus-treated patients experienced erythema/irritation (8% Vs 19%; respectively; p = .039) and itching (8% Vs 20%; respectively; p = .073) (Citation46). On Day 4, the duration of erythema/irritation was significantly shorter with pimecrolimus with no patients in this group experiencing erythema/irritation for more than 30 min compared with 85% of patients in the tacrolimus group (p < .001). Continuous erythema/irritation was experienced by 0% of patients in the pimecrolimus group and 23% of patients in the tacrolimus group (Citation46). Local burning may also be greater with tacrolimus, with up to 36% of pediatric patients and 37% of adults experiencing this side effect after application of the 0.03% ointment compared with 7.4% of pediatric patients and 10.4% of adults after using pimecrolimus 1% cream (Citation54,Citation55).

Finally, results from preclinical studies have demonstrated that topical pimecrolimus has a more favorable balance of anti-inflammatory versus immunosuppressive potential than tacrolimus showing that pimecrolimus has a selective activity profile, suited for the safe effective treatment of inflammatory skin diseases such as AD (Citation53).

Overall, however, the safety profile of pimecrolimus has been more extensively investigated than that of tacrolimus, particularly in infants with AD, with a comprehensive body of clinical studies, post-marketing surveillance and epidemiological investigations revealing no safety concerns with pimecrolimus (Citation56–58). Together, patients’ preference for pimecrolimus and its more favorable safety profile, in terms of lower systemic exposure, less immunosuppressive activity and fewer application site reactions, compared with tacrolimus may lead to better adherence to pimecrolimus, which will ultimately improve clinical outcomes.

TCI versus TCS for sensitive skin areas in mild-to-moderate AD flares

Pimecrolimus also has many advantages compared with TCS for the treatment of mild-to-moderate disease flares in sensitive skin areas. The main advantage of pimecrolimus is that, unlike TCS, it does not cause skin atrophy or further impairment of the epidermal barrier. A randomized 4-week clinical study showed that the TCS, triamcinolone acetonide and betamethasone-17-valerate, both induced a significant reduction in skin thickness compared with pimecrolimus of 12.2% and 7.9%, respectively (p < .001) with significant differences appearing after only 8 days of treatment (Citation59). An additional 3-week study showed an improvement in the ultrastructure of the epidermal barrier after treatment with pimecrolimus, but not betamethasone-17-valerate (Citation60). The detrimental effect of TCS on the epidermal barrier may be due to their negative effect on the expression of certain genes encoding proteins responsible for normal skin barrier function, for example involucrin, which, in contrast, is not observed with pimecrolimus (Citation61,Citation62).

Another study showed that a 2-week single course of topical treatment with a mildly potent steroid can cause transient epidermal thinning, an effect not seen in the pimecrolimus group. Long-term or repeated use of even mild-potency topical corticosteroids at delicate sites such as the face may therefore be of greater concern. Authors concluded that pimecrolimus may be safer for the treatment of AD in sensitive skin areas such as the face, particularly when repeated treatment is required (Citation63).

A study consisting of 972 patients, showed that tacrolimus 0.1% was slightly better, by the physician’s assessment, than low-potency TCS on the face and neck and mid-potency TCS on the trunk and extremities (risk ratio [RR] (95% confidence interval [CI]) 1.32 [1.17, 1.49]) (Citation64), although skin burning was more frequent in those using tacrolimus than TCS (Citation64–67). Similarly, application site burning has been reported in a greater proportion of patients using pimecrolimus when compared with those using TCS (reported in 25.9% and 10.9% of adult patients, respectively) (Citation68). However, several studies indicate that application site burning occurs more frequently in patients using tacrolimus (experienced by up to 36% of pediatric patients (Citation54) and 37% of adult patients using tacrolimus 0.03% ointment (Citation55), and by up to 47% of adult patients applying tacrolimus 0.1% ointment (Citation55,Citation69)) compared with pimecrolimus (experienced by 6.8–7.4% of pediatric patients and 6.8–10.4% of adult patients using pimecolimus 1% cream (Citation40,Citation54,Citation70)).

Although pimecrolimus was shown in the Petite study to have comparable efficacy to low or medium potency TCS (Citation34), evidence has shown that pimecrolimus may even reverse the skin atrophy that is induced by TCS, showing further benefits to its use. In a 6-week clinical study, a significantly greater proportion of patients with TCS-induced skin atrophy, who were treated with pimecrolimus, experienced improved skin atrophy than those treated with vehicle (46.5% Vs 17.6%, p = .02) (Citation35). In addition, the safety profile of pimecrolimus is more favorable than TCS for AD in sensitive areas, as prolonged use of TCS is associated with atrophy, striae, petechiae, telangiectasia, acne and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis suppression (Citation5,Citation71). These side effects are due to the unspecific mode of action of TCS. Furthermore, the permeation of TCS through the skin is 70–110-fold higher than for pimecrolimus, which may increase the risk of systemic side effects further (Citation49). Fear of these side effects have contributed to growing corticophobia over recent years from 72.5% in a study conducted in 2000 (Citation72) to 80.7% in a study conducted in 2011 (Citation73). Correspondingly, the percentage of patients who are not adherent to TCS therapy has increased from 24% (Citation72) to 36% (Citation73) over this time period, indicating that corticophobia leads to suboptimal AD treatment in many patients.

Of relevance to the issue of corticophobia and the multiple side effects associated with TCS is the steroid-sparing effect associated with the use of pimecrolimus. For example, in the Petite study, pimecrolimus-treated patients used TCS for a median of 7 days compared with 178 days in the TCS group over the 5-year study; 36% of patients in the pimecrolimus group did not use any TCS at all during the study (Citation34). The StabiEL study, a 4-month observational study of 3200 patients reported that a greater percentage of TCS-treated patients had concerns about using this treatment on sensitive skin areas compared with those treated with pimecrolimus (79% Vs 27%, respectively) (Citation74). This study showed that pimecrolimus is preferred by patients and their caregivers to TCS over a wide range of treatment considerations including ease of application, tolerability, sleep quality, QoL, well-being, flare prevention, skin stabilization and overall disease control (Citation74). Patients’ preference for pimecrolimus over TCS, together with its more favorable safety profile, may lead to improved adherence with pimecrolimus treatment.

Use of TCI in other body locations

Either pimecrolimus or tacrolimus may be applied as first-line therapy at the first signs and symptoms of AD on other body locations. A network meta-analysis of short- and long-term clinical studies in children and adults with AD have shown that the two TCIs have similar efficacy (Citation47). The results of a comparative study of pimecrolimus 1% cream and tacrolimus 0.03% ointment showed that both TCIs effectively treated AD on the trunk, and upper and lower limbs in pediatric patients with moderate disease (Citation46).

In contrast, a 6-week study in 281 adults with moderate to very severe AD showed that tacrolimus 0.1% ointment was more effective than pimecrolimus 1% cream leading to significantly greater reductions in the Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI), and the percentage of the total body surface area affected (Citation75). Although, less suitable than pimecrolimus for sensitive skin areas, tacrolimus has been shown in clinical studies to provide reductions in the signs and symptoms of AD, improvements in pruritus, improvements in the QoL of AD patients and decreases in the EASI and the percentage body surface area affected in other body locations (Citation76–84).

TCS use for the treatment of severe AD flares

In the current algorithm, TCS are reserved for the short-term treatment of severe disease flares; TCS of class 2 or 3 potency are recommended (Citation71). A low to medium potency TCS should be used to treat severe disease flares on the face and other sensitive areas, whereas a higher potency TCS can be used on other body locations (Citation71). The clinical benefits of TCS for the treatment of AD have been extensively investigated in over 110 randomized controlled trials (Citation27,Citation85). They effectively and rapidly control disease flares through their anti-inflammatory, anti-proliferative and immunosuppressive actions (Citation2,Citation5). The results of a real-life study in which 2034 patients used pimecrolimus at the first signs or symptoms of eczema and in which severe flares were treated with TCS showed that after 3 months, 59.0% of patients were clear or almost clear of disease (Citation70). Although potent, TCS can effectively resolve severe AD flares however, their use should be restricted to short-term intervention, due to their potential for multiple local and systemic side effects (Citation71).

TCI use for proactive therapy

Proactive therapy with TCI is recommended in current treatment guidelines (Citation3,Citation27,Citation29). It usually involves the application of TCI to previously affected areas of the skin, in a twice-weekly regimen. This helps reduce the risk of subsequent relapses and decreases the need for TCS. Proactive treatment with pimecrolimus applied to previously affected areas of skin has been shown to effectively prevent AD flares. The results of one study showed that only a minority of patients had a disease relapse, defined as AD worsening requiring TCS use, with proactive pimecrolimus treatment over 16 weeks (Citation86). In addition, proactive treatment with tacrolimus has also been shown to be associated with clinical benefits such as a significantly greater number of disease-free days (mean: 174 days for tacrolimus Vs 107 days for vehicle, p = .0008), a significant reduction in the number of flares and a significantly longer time to first relapse compared with the vehicle (116 days for tacrolimus Vs 31 days for vehicle, p = .04) (Citation87–91). Robust long-term safety data on TCI also supports their use as standard-of-care proactive therapy (Citation58). However, the use of TCS for proactive therapy over a prolonged period of time is unsuitable due to their negative effect on the epidermal barrier and their multiple treatment-related side effects (Citation71).

Conclusions

AD is a common skin disease in countries across the Middle East and has a major impact on the QoL of patients and their families. The treatment algorithm presented here is the first specifically developed for AD patients in the Middle East. Evidence has shown that pimecrolimus should be recommended as the treatment of choice for mild to moderate AD affecting sensitive skin areas. This recommendation is based on the overall efficacy, patient preference and safety profile of pimecrolimus compared with tacrolimus for the treatment of such areas. TCS are considered unsuitable for sensitive areas as they cause skin atrophy and further impairment of the epidermal barrier. Furthermore, studies have shown patients prefer pimecrolimus to both tacrolimus and TCS. Both TCIs are recommended for moderate AD on other body locations (pimecrolimus is indicated for mild-to-moderate AD while tacrolimus is indicated for moderate-to-severe cases), whereas TCS should be reserved for the short-term treatment of severe flares. These recommendations are therefore expected to optimize the management of AD in patients across the Middle East who suffer from this distressing skin disease.

Acknowledgments

Medical writing assistance in the preparation of this manuscript was provided by David Harrison, (Medscript Ltd) and Laura Brennan (CircleScience, an Ashfield Company, part of UDG Healthcare plc).

Disclosure statement

AMR, AE, AIE, MSA, MSQ, MMRA reported no conflict of interest. TL has conducted clinical trials or received honoraria for serving as a member of the Scientific Advisory Board for Abbvie, Biogen-IDEC, Celgene, CERIES, Galderma, Eli-Lilly, Janssen-Cilag, La Roche Posay, Maruho, Meda, MSD, Mundipharma, Mylan, Novartis, Pfizer, Sandoz, Sanofi-Aventis, Symrise and Wolff.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Akdis CA, Akdis M, Bieber T, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of atopic dermatitis in children and adults: European Academy of Allergology and Clinical Immunology/American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology/PRACTALL Consensus Report. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;118:152–169.

- Wollenberg A, Oranje A, Deleuran M, et al. ETFAD/EADV Eczema task force 2015 position paper on diagnosis and treatment of atopic dermatitis in adult and paediatric patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:729–747.

- Ring J, Alomar A, Bieber T, et al. Guidelines for treatment of atopic eczema (atopic dermatitis) part I. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26:1045–1060.

- Garmhausen D, Hagemann T, Bieber T, et al. Characterization of different courses of atopic dermatitis in adolescent and adult patients. Allergy. 2013;68:498–506.

- Watson W, Kapur S. Atopic dermatitis. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol. 2011;7(Suppl 1):S4.

- Wollina U. Microbiome in atopic dermatitis. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2017;10:51–56.

- Kabashima K, Otsuka A, Nomura T. Linking air pollution to atopic dermatitis. Nat Immunol. 2016;18:5–6.

- Spergel JM, Paller AS. Atopic dermatitis and the atopic march. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;112:S118–S127.

- Farajzadeh S, Esfandiarpour I, Sedaghatmanesh M, et al. Epidemiology and clinical features of atopic dermatitis in Kerman, a desert area of Iran. Ann Dermatol. 2014;26:26–34.

- Darlenski R, Kazandjieva J, Hristakieva E, et al. Atopic dermatitis as a systemic disease. Clin Dermatol. 2014;32:409–413.

- Hjuler KF, Bottcher M, Vestergaard C, et al. Increased prevalence of coronary artery disease in severe psoriasis and severe atopic dermatitis. Am J Med. 2015;128:1325–1334.

- Wohl Y, Wainstein J, Bar-Dayan Y. Atopic dermatitis in Israeli adolescents - a large retrospective cohort study. Acta Derm Venereol. 2014;94:695–698.

- Romano-Zelekha O, Graif Y, Garty BZ, et al. Trends in the prevalence of asthma symptoms and allergic diseases in Israeli adolescents: results from a national survey 2003 and comparison with 1997. J Asthma. 2007;44:365–369.

- Mohammad Y, Tabbah K, Mohammad S, et al. International study of asthma and allergies in childhood: phase 3 in the Syrian Arab Republic. East Mediterr Health J. 2010;16:710–716.

- Rahimi Rad MH, Hejazi ME, Behrouzian R. Asthma and other allergic diseases in 13-14-year-old schoolchildren in Urmia, Iran. [corrected]. East Mediterr Health J. 2007;13:1005–1016.

- Behbehani NA, Abal A, Syabbalo NC, et al. Prevalence of asthma, allergic rhinitis, and eczema in 13- to 14-year-old children in Kuwait: an ISAAC study. International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2000;85:58–63.

- Al-Riyami BM, Al-Rawas OA, Al-Riyami AA, et al. A relatively high prevalence and severity of asthma, allergic rhinitis and atopic eczema in schoolchildren in the Sultanate of Oman. Respirology. 2003;8:69–76.

- Sabry EY. Prevalence of allergic diseases in a sample of Taif citizens assessed by an original Arabic questionnaire (phase I) A pioneer study in Saudi Arabia. Allergol Immunopathol (Madr). 2011;39:96–105.

- Alzolibani AA. Impact of atopic dermatitis on the quality of life of Saudi children. Saudi Med J. 2014;35:391–396.

- Mozaffari H, Pourpak Z, Pourseyed S, et al. Quality of life in atopic dermatitis patients. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2007;40:260–264.

- Al Robaee AA, Shahzad M. Impairment quality of life in families of children with atopic dermatitis. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2010;18:243–247.

- Al Shobaili HA. The impact of childhood atopic dermatitis on the patients’ family. Pediatr Dermatol. 2010;27:618–623.

- Kemp AS. Cost of illness of atopic dermatitis in children: a societal perspective. Pharmacoeconomics. 2003;21:105–113.

- Li AW, Yin ES, Antaya RJ. Topical Corticosteroid Phobia in Atopic Dermatitis: A Systematic Review. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:1036–1042

- Ring J, Alomar A, Bieber T, et al. Guidelines for treatment of atopic eczema (atopic dermatitis) Part II. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26:1176–1193.

- Eichenfield LF, Tom WL, Chamlin SL, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: section 1. Diagnosis and assessment of atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:338–351.

- Eichenfield LF, Tom WL, Berger TG, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: section 2. Management and treatment of atopic dermatitis with topical therapies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:116–132.

- Sidbury R, Davis DM, Cohen DE, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: section 3. Management and treatment with phototherapy and systemic agents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:327–349.

- Sidbury R, Tom WL, Bergman JN, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: Section 4. Prevention of disease flares and use of adjunctive therapies and approaches. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:1218–1233.

- Breuer K, Braeutigam M, Kapp A, et al. Influence of pimecrolimus cream 1% on different morphological signs of eczema in infants with atopic dermatitis. Dermatology (Basel). 2004;209:314–320.

- Severity scoring of atopic dermatitis: the SCORAD index. Consensus Report of the European Task Force on Atopic Dermatitis. Dermatology. 1993;186:23–31.

- Werfel T, Schwerk N, Hansen G, et al. The diagnosis and graded therapy of atopic dermatitis. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2014;111:509–520.

- Luger T, De Raeve L, Gelmetti C, et al. Recommendations for pimecrolimus 1% cream in the treatment of mild-to-moderate atopic dermatitis: from medical needs to a new treatment algorithm. Eur J Dermatol. 2013;23:758–766.

- Sigurgeirsson B, Boznanski A, Todd G, et al. Safety and efficacy of pimecrolimus in atopic dermatitis: a 5-year randomized trial. Pediatrics. 2015;135:597–606.

- Murrell DF, Calvieri S, Ortonne JP, et al. A randomized controlled trial of pimecrolimus cream 1% in adolescents and adults with head and neck atopic dermatitis and intolerant of, or dependent on, topical corticosteroids. Br J Dermatol. 2007;157:954–959.

- Hoeger PH, Lee KH, Jautova J, et al. The treatment of facial atopic dermatitis in children who are intolerant of, or dependent on, topical corticosteroids: a randomized, controlled clinical trial. Br J Dermatol. 2009;160:415–422.

- Lübbe J, Friedlander SF, Cribier B, et al. Safety, efficacy, and dosage of 1% pimecrolimus cream for the treatment of atopic dermatitis in daily practice. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2006;7:121–131.

- Kaufmann R, Bieber T, Helgesen AL, et al. Onset of pruritus relief with pimecrolimus cream 1% in adult patients with atopic dermatitis: a randomized trial. Allergy. 2006;61:375–381.

- Fowler J, Johnson A, Chen M, et al. Improvement in pruritus in children with atopic dermatitis using pimecrolimus cream 1%. Cutis. 2007;79:65–72.

- Meurer M, Folster-Holst R, Wozel G, et al. Pimecrolimus cream in the long-term management of atopic dermatitis in adults: a six-month study. Dermatology (Basel). 2002;205:271–277.

- Wahn U, Bos JD, Goodfield M, et al. Efficacy and safety of pimecrolimus cream in the long-term management of atopic dermatitis in children. Pediatrics. 2002;110:e2.

- Sigurgeirsson B, Ho V, Ferrandiz C, et al. Effectiveness and safety of a prevention-of-flare-progression strategy with pimecrolimus cream 1% in the management of paediatric atopic dermatitis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:1290–1301.

- Gollnick H, Kaufmann R, Stough D, et al. Pimecrolimus cream 1% in the long-term management of adult atopic dermatitis: prevention of flare progression. A randomized controlled trial. Br J Dermatol. 2008;158:1083–1093.

- McKenna SP, Whalley D, de Prost Y, et al. Treatment of paediatric atopic dermatitis with pimecrolimus (Elidel, SDZ ASM 981): impact on quality of life and health-related quality of life. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venerol. 2006;20:248–254.

- Staab D, Kaufmann R, Brautigam M, et al. Treatment of infants with atopic eczema with pimecrolimus cream 1% improves parents’ quality of life: a multicenter, randomized trial. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2005;16:527–533.

- Kempers S, Boguniewicz M, Carter E, et al. A randomized investigator-blinded study comparing pimecrolimus cream 1% with tacrolimus ointment 0.03% in the treatment of pediatric patients with moderate atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:515–525.

- Huang X, Xu B. Efficacy and Safety of Tacrolimus versus Pimecrolimus for the Treatment of Atopic Dermatitis in Children: A Network Meta-Analysis. Dermatology. 2015;231:41–49.

- Paller AS, Lebwohl M, Fleischer AB Jr, et al. Tacrolimus ointment is more effective than pimecrolimus cream with a similar safety profile in the treatment of atopic dermatitis: results from 3 randomized, comparative studies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:810–822.

- Billich A, Aschauer H, Aszodi A, et al. Percutaneous absorption of drugs used in atopic eczema: pimecrolimus permeates less through skin than corticosteroids and tacrolimus. Int J Pharm. 2004;269:29–35.

- Weiss HM, Fresneau M, Moenius T, et al. Binding of pimecrolimus and tacrolimus to skin and plasma proteins: implications for systemic exposure after topical application. Drug Metab Dispos. 2008;36:1812–1818.

- Allen BR, Lakhanpaul M, Morris A, et al. Systemic exposure, tolerability, and efficacy of pimecrolimus cream 1% in atopic dermatitis patients. Arch Dis Child. 2003;88:969–973.

- Draelos Z, Nayak A, Pariser D, et al. Pharmacokinetics of topical calcineurin inhibitors in adult atopic dermatitis: a randomized, investigator-blind comparison. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:602–609.

- Grassberger M, Steinhoff M, Schneider D, et al. Pimecrolimus – an anti-inflammatory drug targeting the skin. Exp Dermatol. 2004;13:721–730.

- Lynde C, Barber K, Claveau J, et al. Canadian practical guide for the treatment and management of atopic dermatitis. J Cutan Med Surg. 2005;8(Suppl 5):1–9.

- Ruzicka T, Bieber T, Schopf E, et al. A short-term trial of tacrolimus ointment for atopic dermatitis. European Tacrolimus Multicenter Atopic Dermatitis Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:816–821.

- Luger T, Boguniewicz M, Carr W, et al. Pimecrolimus in atopic dermatitis: consensus on safety and the need to allow use in infants. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2015;26:306–315.

- Langley RG, Luger TA, Cork MJ, et al. An update on the safety and tolerability of pimecrolimus cream 1%: evidence from clinical trials and post-marketing surveillance. Dermatology (Basel). 2007;215 (Suppl 1):27–44.

- Siegfried EC, Jaworski JC, Kaiser JD, et al. Systematic review of published trials: long-term safety of topical corticosteroids and topical calcineurin inhibitors in pediatric patients with atopic dermatitis. BMC Pediatr. 2016;16:75.

- Queille-Roussel C, Paul C, Duteil L, et al. The new topical ascomycin derivative SDZ ASM 981 does not induce skin atrophy when applied to normal skin for 4 weeks: a randomized, double-blind controlled study. Br J Dermatol. 2001;144:507–513.

- Jensen JM, Pfeiffer S, Witt M, et al. Different effects of pimecrolimus and betamethasone on the skin barrier in patients with atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;124:R19–R28.

- Grzanka A, Zebracka-Gala J, Rachowska R, et al. The effect of pimecrolimus on expression of genes associated with skin barrier dysfunction in atopic dermatitis skin lesions. Exp Dermatol. 2012;21:184–188.

- Jensen JM, Scherer A, Wanke C, et al. Gene expression is differently affected by pimecrolimus and betamethasone in lesional skin of atopic dermatitis. Allergy. 2012;67:413–423.

- Aschoff R, Schmitt J, Knuschke P, et al. Evaluation of the atrophogenic potential of hydrocortisone 1% cream and pimecrolimus 1% cream in uninvolved forehead skin of patients with atopic dermatitis using optical coherence tomography. Exp Dermatol. 2011;20:832–836.

- Cury Martins J, Martins C, Aoki V, et al. Topical tacrolimus for atopic dermatitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;CD009864.

- Reitamo S, Harper J, Bos JD, et al. 0.03% Tacrolimus ointment applied once or twice daily is more efficacious than 1% hydrocortisone acetate in children with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis: results of a randomized double-blind controlled trial. Br J Dermatol. 2004;150:554–562.

- Reitamo S, Van Leent EJ, Ho V, et al. Efficacy and safety of tacrolimus ointment compared with that of hydrocortisone acetate ointment in children with atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2002;109:539–546.

- Ashcroft DM, Dimmock P, Garside R, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of topical pimecrolimus and tacrolimus in the treatment of atopic dermatitis: meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 2005;330:516.

- Luger TA, Lahfa M, Folster-Holst R, et al. Long-term safety and tolerability of pimecrolimus cream 1% and topical corticosteroids in adults with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis. J Dermatolog Treat. 2004;15:169–178.

- Reitamo S, Wollenberg A, Schopf E, et al. Safety and efficacy of 1 year of tacrolimus ointment monotherapy in adults with atopic dermatitis. The European Tacrolimus Ointment Study Group. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:999–1006.

- Ring J, Abraham A, de Cuyper C, et al. Control of atopic eczema with pimecrolimus cream 1% under daily practice conditions: results of a >2000 patient study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:195–203.

- Hengge UR, Ruzicka T, Schwartz RA, et al. Adverse effects of topical glucocorticosteroids. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:1–15. quiz 16–18.

- Charman CR, Morris AD, Williams HC. Topical corticosteroid phobia in patients with atopic eczema. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:931–936.

- Aubert-Wastiaux H, Moret L, Le Rhun A, et al. Topical corticosteroid phobia in atopic dermatitis: a study of its nature, origins and frequency. Br J Dermatol. 2011;165:808–814.

- Gollnick H, Luger T, Freytag S, et al. StabiEL: stabilization of skin condition with Elidel–a patients' satisfaction observational study addressing the treatment, with pimecrolimus cream, of atopic dermatitis pretreated with topical corticosteroid. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:1319–1325.

- Fleischer AB, Jr., Abramovits W, Breneman D, et al. Tacrolimus ointment is more effective than pimecrolimus cream in adult patients with moderate to very severe atopic dermatitis. J Dermatolog Treat. 2007;18:151–157.

- Boguniewicz M, Fiedler VC, Raimer S, et al. A randomized, vehicle-controlled trial of tacrolimus ointment for treatment of atopic dermatitis in children. Pediatric Tacrolimus Study Group. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1998;102:637–644.

- Kang S, Lucky AW, Pariser D, et al. Long-term safety and efficacy of tacrolimus ointment for the treatment of atopic dermatitis in children. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44:S58–S64.

- Paller A, Eichenfield LF, Leung DY, et al. A 12-week study of tacrolimus ointment for the treatment of atopic dermatitis in pediatric patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44:S47–S57.

- Hanifin JM, Ling MR, Langley R, et al. Tacrolimus ointment for the treatment of atopic dermatitis in adult patients: part I, efficacy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44:S28–S38.

- Chapman MS, Schachner LA, Breneman D, et al. Tacrolimus ointment 0.03% shows efficacy and safety in pediatric and adult patients with mild to moderate atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:S177–S185.

- Reitamo S, Rustin M, Harper J, et al. A 4-year follow-up study of atopic dermatitis therapy with 0.1% tacrolimus ointment in children and adult patients. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159:942–951.

- Drake L, Prendergast M, Maher R, et al. The impact of tacrolimus ointment on health-related quality of life of adult and pediatric patients with atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44:S65–S72.

- Kawashima M. Quality of life in patients with atopic dermatitis: impact of tacrolimus ointment. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:731–736.

- Poole CD, Chambers C, Allsopp R, et al. Quality of life and health-related utility analysis of adults with moderate and severe atopic dermatitis treated with tacrolimus ointment vs. topical corticosteroids. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;24:674–678.

- Hoare C, Li Wan Po A, Williams H. Systematic review of treatments for atopic eczema. Health Technol Assess. 2000;4:1–191.

- Ruer-Mulard M, Aberer W, Gunstone A, et al. Twice-daily versus once-daily applications of pimecrolimus cream 1% for the prevention of disease relapse in pediatric patients with atopic dermatitis. Pediatr. Dermatol. 2009;26:551–558.

- Paller AS, Eichenfield LF, Kirsner RS, et al. Three times weekly tacrolimus ointment reduces relapse in stabilized atopic dermatitis: a new paradigm for use. Pediatrics. 2008;122:e1210–e1218.

- Reitamo S, Allsopp R. Treatment with twice-weekly tacrolimus ointment in patients with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis: results from two randomized, multicentre, comparative studies. J Dermatolog Treat. 2010;21:34–44.

- Breneman D, Fleischer AB Jr, Abramovits W, et al. Intermittent therapy for flare prevention and long-term disease control in stabilized atopic dermatitis: a randomized comparison of 3-times-weekly applications of tacrolimus ointment versus vehicle. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:990–999.

- Thaci D, Reitamo S, Gonzalez Ensenat MA, et al. Proactive disease management with 0.03% tacrolimus ointment for children with atopic dermatitis: results of a randomized, multicentre, comparative study. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159:1348–1356.

- Wollenberg A, Reitamo S, Girolomoni G, et al. Proactive treatment of atopic dermatitis in adults with 0.1% tacrolimus ointment. Allergy. 2008;63:742–750.