Abstract

If an authorized drug is prescribed for a use that is not described in the Summary of Product Characteristics, this is defined as ‘off-label use.’ Methotrexate is often used off-label for dermatological indications. Off-label use is permitted if physicians can justify the treatment based on scientific evidence available to them. Our objective here was therefore to summarize the evidence for the effectiveness, efficacy, and safety of the dermatological off-label use of methotrexate in a systematic review. We searched MEDLINE, EMBASE, and CENTRAL for studies for evidence on the effectiveness, efficacy, and safety of the off-label use of methotrexate in dermatological indications up to November 2019. We used the GRADE system to rate the quality of the evidence. The search retrieved 34,583 hits of which 3566 were selected after the title and abstract screening. After the full-text screening, 143 studies were included, which involved 3688 patients in total. We found low-quality evidence for the effectiveness, efficacy, and safety of the off-label use of methotrexate in 31 dermatological diseases. To optimize the quality of evidence to support off-label use, we need high-quality studies in which well-characterized patients are treated with standardized treatments regimens using well-validated outcomes relevant to patients and physicians.

Keywords:

Introduction

Off-label prescriptions are common in dermatology, ranging from 14 to 73% of cases (Citation1–3). ‘Off-label use’ refers to an authorized drug (often authorized by the European Medicines Agency or the U.S. Food And Drug Administration) that is prescribed for an indication that is not described in the Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC). The SmPC contains the authorized terms of use – such as indication, dosage, and frequency – of the product (Citation4). Examples of drugs frequently prescribed for off-label use in dermatology are azathioprine and dapsone (Citation5,Citation6). The frequent prescription of off-label therapies in dermatology may be due to the time needed for market approval for specific indications and the fact that over 3000 skin diseases exist (Citation1). The high costs of designing and developing a new drug and the considerable time needed for its approval – combined with the low revenue from an expiring drug patent – may also play a role (Citation3).

Methotrexate (MTX) is regularly prescribed for off-label use in dermatology as it is only registered for psoriasis vulgaris and mycosis fungoides. A recent survey study showed that almost one-third of all participating dermatologists preferred MTX as their first choice of therapy for atopic dermatitis (AD) (Citation7). The use of MTX has many advantages: it is widely available, the safety profile is well-known and it is a low-cost treatment (Citation8,Citation9). No European-level legislation covers the prescription of drugs for off-label use; this is delegated to individual Member States (Citation10). Off-label prescription is permitted in the Netherlands as long as certain guidelines are followed (Citation11); physicians have to make sure that the patients and pharmacists concerned are aware that the drug is being prescribed for off-label use. The prescribing physicians should also be able to justify the off-label use based on the available scientific evidence and guidelines, and the risk-benefit balance of the treatment for patients must be positive (Citation1,Citation12).

Three overviews of the off-label use of MTX in dermatology have been published previously: Shen et al. and Diani et al. published reviews (Citation13,Citation14), and in 2016 the British Association of Dermatologists published a guideline for the prescription of MTX in dermatology, which also provided an overview of the available evidence in off-label MTX use in dermatology (Citation15). With our systematic review (SR) we aimed to support the clinical practice by giving a complete overview of current evidence (including case series) for the dermatoses for which MTX is being used off-label. To assess the studies in our review, where possible we used the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) system (Citation16).

Materials and methods

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

This systematic review was registered in Prospero (registration number: CRD42018081028) (Citation17). We did not publish a protocol. All randomized controlled trials (RCTs), cohort studies, and case series (with ≥5 patients) in which MTX was used off-label in a dermatological disease and in which the effectiveness, efficacy, and/or safety was discussed, were included. We made this decision since we could provide far fewer indications for which MTX is currently being used if we decided to narrow our inclusion criteria to RCTs and observational studies only. If articles discussed information about off-label MTX use in a multi-organ disease, these were included if the information on effectiveness/efficacy on dermatological abnormalities was also given. If patients had systemic disease, only those with cutaneous involvement were described. Many studies provided information on a combination of off-label MTX with other treatments. In this SR we decided to include only studies that combined corticosteroids (topical, oral, intramuscular, or intravenous) or folic acid with MTX. We excluded reviews, duplicate publications, conference abstracts, questionnaire-based surveys, articles for which the full text was not available, articles in languages other than English, French, German or Dutch, articles in which on-label, topical or intralesional use of MTX or only side-effects of MTX were discussed, animal studies, and in-vitro studies.

Literature search

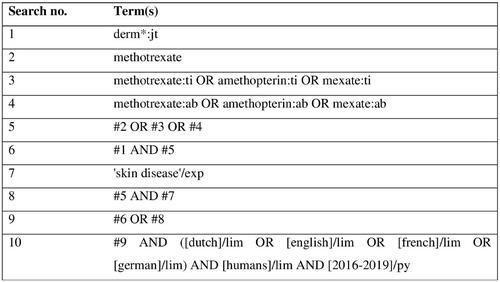

The MEDLINE and EMBASE databases were searched up to November 6, 2019. The CENTRAL database was searched up to November 13, 2019. We also searched the reference lists of the included articles for eligible articles. The complete search strategy can be found in .

Study selection and data extraction

First, all search results were merged and duplicates were removed. The titles and/or abstracts were screened by two independent researchers. Of the selected articles, the full text was retrieved and screened for eligibility by the same authors, taking the inclusion- and exclusion criteria into account. Reasons for exclusions were documented.

Data extraction was performed by two independent researchers and collected digitally on predefined data-extraction forms. We collected data on the publication date, study population (number, age, sex, type of dermatologic disease, and previous therapies), study design (study type), concomitant medication, duration of treatment and follow-up, the dosage of MTX, efficacy/effectiveness, including the type of outcomes used, time to effect and duration of remission if available, and safety data. To give a complete overview of the collected data we choose to display them in tables. Data on adverse events (AEs) and serious adverse events (SAEs) were also collected. SAEs were defined as any untoward medical occurrence during drug treatment that required inpatient hospitalization or prolonging of existing hospitalization, was life-threatening, resulted in persistent or significant disability/incapacity, was a congenital anomaly/birth defect, or was reported in the study as such or that resulted in death.

Whenever possible, data were reported with a mean and a range. For outcome measurements, changes in mean from baseline to end of treatment were reported. As a consequence of the heterogeneity of these outcome measurements, a meta-analysis was not possible.

For all stages of study selection and data extraction, discrepancies were resolved by discussion and, if needed, a third researcher (PS) was consulted.

Data-analysis – GRADE approach

For the evaluation of the quality of evidence, we used the GRADE rating system by the criteria (Citation18). This system places the quality of an outcome into one of four categories; very low, low, moderate, or high (Citation19). As the outcomes from the case series and cohort studies in the included studies would very likely be rated as very low, GRADE evidence profiles were only made for RCTs. Risk ratio’s and absolute risk differences used in GRADE evidence profiles were calculated with the Review Manager (RevMan). To ensure the quality of the reporting in this SR, we followed the PRISMA statement (Citation20). The PRISMA Checklist can be found in Supplementary Material I.

Results

Study selection and data-extraction

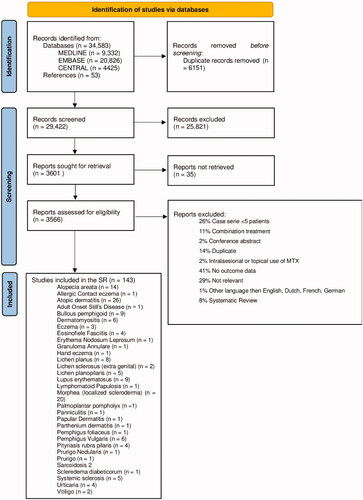

summarizes the selection process. The literature search identified 34,583 hits of which 6151 were duplicates. After screening based on title/abstract, 3566 studies were selected. Articles were mainly excluded due to lack of relevance (e.g. MTX in a non-skin disease) or due to the absence of a skin effectiveness outcome (Citation21). After the full-text screening, 143 articles were included, comprising 14 RCTs, 29 cohort studies, and 100 case series. Although some studies did not state exactly how many patients they included (Citation22), in total about 3688 patients with 31 different dermatologic diseases were included.

Data extraction

The most salient results per disease are listed below. provides an overview of the extracted study characteristics on RCTs and observational studies. Table S1 shows the details of all extracted study characteristics. Unknown values are reported as ‘Unk;’ if not reported, ranges of age, treatment duration, maximum duration, maximum dose, mean duration of remission, and male/female ratio are left empty to compress the format of the tables.

Table 1. Characteristics of included RCTs and observational studies, see Supplemental II for the characteristics of all included studies.

Concomitant medication was used in almost all included studies; in 22 articles this concomitant use was not reported. In 40 of the 143 studies corticosteroids were used in combination with MTX. Prednisone was the concomitant medication most frequently prescribed (n = 39). In 12 studies the use of systemic corticosteroids was described in general without specification of systemic or topical use. Four studies reported the corticosteroid-sparing effect of MTX as an outcome (Citation23–26). The concomitant use of folic acid was mentioned in 47 studies; the dosage ranged between 1–5 mg daily (Citation27–42) and 5–25 mg weekly (Citation43–49). Dosages or frequencies were often not described (Citation50–73). The maximum reported treatment duration was 132 months (Citation31), but most study patients were treated for a mean duration of <24 months. The dosage of MTX ranged from 0.2 mg/kg daily to 37.5 mg weekly. In children MTX was usually prescribed according to body weight: mg/kg (Citation57) or mg/m2 [74]. The outcome measures that were used were very heterogeneous; primary outcome measures from RCTs and observational studies are shown in . The details of all studies are described in Table S2. The time-to-effect and mean duration of disease remission were frequently absent, but in the studies that reported these variables they ranged from 1 to 104 weeks (time-to-effect) and from 2.5 to 121 months (mean duration of disease remission). Details of the reported AEs and SAEs are shown in Table S2. However, 21 studies did not report AEs and 61 did not report SAEs.

Table 2. Efficacy and effectiveness of included RCTs and observational studies, see Supplemental II for the efficacy and effectiveness of all included studies.

Data analysis – GRADE approach

The quality of the evidence of the RCTs is shown in the GRADE evidence profiles (Tables S3–S14).

Results per disease

Alopecia areata (AA)

We included 14 studies on this disease (Citation59,Citation60,Citation68,Citation74–84), comprising a total of 285 patients. Half of these studies were retrospective case series (n = 7); no RCTs were found, and four case series included only children (Citation59,Citation79,Citation82,Citation83). In all case series about half of the patients experienced hair regrowth of at least 50%. In the case series that reported 100% hair regrowth, MTX treatment was combined with at least one topical or systemic corticosteroid.

Juvenile and adult atopic dermatitis (AD)

We included 26 studies on AD comprising a total of 1056 patients. This was the largest group in this SR. These studies consisted of three RCTs, two observational follow-up studies, five retrospective cohorts and 16 case series (Citation22,Citation29,Citation31,Citation43,Citation44,Citation46,Citation52,Citation55,Citation57,Citation62,Citation64,Citation70,Citation85–98). In the RCT of El-Khalawany (Citation64), in which MTX was compared to ciclosporin in 40 children, no significant difference in SCORing Atopic Dermatitis index (SCORAD) reduction was found (Table S3. GRADE evidence profile). Goujon et al. (Citation29) compared MTX to ciclosporin in 147 adults (Table S4. GRADE evidence profile). On their primary endpoint (SCORAD 50, which means a SCORAD reduction of 50% after eight weeks) they found that MTX was inferior to ciclosporin, while after 20 weeks the clinical improvement was similar. Schram et al. (Citation44) compared MTX to azathioprine in 42 adults with a primary endpoint at 12 weeks and a follow-up until 24 weeks (Table S5. GRADE evidence profile). This study showed that SCORAD reduction scores from MTX treatment were similar to azathioprine treatment. These findings were confirmed by two-year observational follow-up studies: a two-year study by Roekevisch et al. (Citation43) and a five-year study by Gerbens et al. (Citation88). In the 16 case series, MTX was effective in approximately half of the patients.

Bullous pemphigoid (BP)

For this disease, we found nine case series (Citation36,Citation48,Citation63,Citation99–104) of which two were prospective. In total 249 patients were enrolled. In the study of Heilborn et al. (Citation63), a total of eleven elderly patients were treated, and all responded in the first month. Outcome measurements in all studies were clearance of disease or good response, remission of disease, or long-term disease control. These case series reported successful treatment in 80–100% of the patients.

Juvenile and adult dermatomyositis (DM)

In the literature search, six studies were found, including one RCT (Citation105), one cohort study (Citation106), and four case series (Citation26,Citation28,Citation107,Citation108) comprising a total of 119 patients. Ramanan et al. (Citation106) and Ruperto et al. (Citation105) studied the juvenile form of DM, the other studies included adults only. Ruperto et al. (Citation105) conducted a multicenter, randomized, open-label superiority trial. A total of 139 patients were included of which 47 were randomized to prednisone alone, 46 received MTX combined with ciclosporin, and 46 prednisone with MTX (Table S6. GRADE evidence profile). After six months, 51% of the patients in the prednisone group, 70% of the patients in the prednisone/ciclosporin group, and 72% patients in the prednisone/MTX group achieved the specific PRINTO20 score from the Pediatric Rheumatology International Trials Organization (Citation105) (p = .0228; the difference between prednisone alone and the two combination groups). The case series and cohort study imply MTX can be effective in prednisone tapering and disease reduction.

Eczema (other than atopic dermatitis)

We included one cohort study (Citation109) and two retrospective case series (Citation49,Citation110), comprising a total of 61 patients. The two case series focused specifically on eczema in the elderly (mean ages 74.4 [110] and 78 [49] years). The cohort study (Citation109) reported on different subtypes of eczema in one study (atopic/pompholyx/discoid/unclassified). In that study 15 of 41 patients achieved the effectiveness outcome ‘control of disease.’ In the elderly eczema studies, effectiveness was assessed as a good or complete response, which was achieved by 15 of 20 patients.

Eosinophilic fasciitis (EF)

We included four studies on this disease comprising 45 patients. The prospective cohort study from Mertens et al. (Citation45) reported a median difference in modified skin score of nine points. The retrospective cohort study from Kroft et al. (Citation71) included five patients with EF but did not report effectiveness. The included case series (Citation111,Citation112) reported improvement in 60–80% of EF patients when treated with MTX alone or combined with corticosteroids.

Lupus erythematosus (LE)

We included two RCTs, six case series, and one cohort study comprising a total of 211 patients. The RCT from Carneiro et al. (Citation113) enrolled 41 patients, of which 21 received MTX and the other 20 placebo. Only 28 patients had skin involvement (Table S7. GRADE evidence profile). Both treatment groups received concomitant systemic corticosteroids. In the MTX group, 12 patients had cutaneous lesions at the start of the study. This fell to three patients after six months of treatment. The 16 patients with placebo and cutaneous lesions showed no reduction. This difference was significant (p < .001). Islam et al. (Citation114) enrolled 42 patients with cutaneous and articular lupus erythematosus; 13 patients received MTX and 29 patients chloroquine (Table S8. GRADE evidence profile). At the start of the study, six patients in the MTX group and 19 patients in the chloroquine group had a skin rash. After 24 weeks this number fell to zero patients in the MTX group and three patients in the chloroquine group (no significant difference). In the cohort study and case series (Citation33,Citation54,Citation115–119) at least half of the patients showed a clinical response >50%.

Lichen planus (LP)

We included two cohort studies (Citation32,Citation39) and six case series (Citation27,Citation38,Citation120–123) comprising a total of 155 patients (generalized, mucocutaneous, and vulvovaginal) who were treated with MTX. Effectiveness was assessed using the percentage of patients achieving complete response, remission, or reduction in disease severity. The use of MTX for the treatment of LP led to a complete response, substantial improvement, or symptom relief in all treated patients.

Lichen planopilaris (LPP)

We included two RCTs and three retrospective case series comprising a total of 141 patients (Citation124–128). Bakhtiar et al. (Citation127) conducted an RCT in which 79 patients with generalized lichen planus were treated with MTX and 79 patients were treated with oral corticosteroids (Table S9. GRADE evidence profile). The responses were analyzed after eight weeks by a Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) from 0 to 10, where 6–7 was considered a good response and >7 an excellent response. MTX was effective in 80% of the patients and oral corticosteroids in 72%; no significant difference was found. The RCT from Naeini et al. (Citation128) enrolled 29 patients, of which 15 were treated with MTX and 14 with hydroxychloroquine for six months (Table S10. GRADE evidence profile). Efficacy was assessed using the Lichen Planopilaris Activity Index (LPPAI). After six months the mean decrease in LPPAI in the MTX group was significantly higher than in the hydroxychloroquine group (3.3. [2.09] vs. 1.51 [0.91], p = .01).

In the case series of Bulbul Baskan (Citation125), the clinical response of MTX vs. ciclosporin treatment was compared. They reported a clinical response of 100% in both groups (Citation125). In all case series, a total of 47 patients were enrolled; 80–100% of the patients showed at least partial clinical response (Citation124–126).

Morphea (M, localized scleroderma)

We included 20 studies – one RCT, four cohort studies, and 15 case series studies – comprising a total of 644 patients; 14 of these studies involved children (Citation30,Citation35,Citation41,Citation51,Citation56,Citation61,Citation67,Citation69,Citation129–134). One RCT on juvenile morphea was found (Zulian et al.) (Citation51) that enrolled 70 patients (46 in the MTX group, 24 in the placebo group). Both groups received oral prednisone for the first three months (Table S11. GRADE evidence profile). The response was quantified clinically (physician’s and patient’s global assessment and Childhood Health Assessment questionnaires), by thermography, and by a computerized scoring system (CSS). Zulian et al. reported an initial response in all patients, with a relapse in 15 MTX-treated patients (32.6%) and 17 placebo-treated patients (70.8%). The mean skin score (measured with the CSS) decreased in the MTX group, but not in the placebo group. The case series (Citation35,Citation41,Citation42,Citation50,Citation56,Citation61,Citation67,Citation69,Citation129,Citation132–137) and cohort studies (Citation30,Citation65,Citation130,Citation131) involved a total 527 patients Various outcomes were measured, including clinical response and improvement of the modified Localized Scleroderma Severity Index (mLoSSI). A good response was shown by 80–100% of the patients.

Pityriasis rubra pilaris (PRP)

We included four small case series on the use of MTX in patients with PRP (Citation138–141) comprising 24 patients in total. The responses varied from the poor response in all participants (Citation138) to complete clearance in all participants (Citation140,Citation141).

Pemphigus vulgaris (PV)

We included six case series comprising 152 patients in total. Lever et al. (Citation142) studied 24 patients with PV that were treated with MTX and prednisone. They concluded that patients who receive MTX in the early phase of their disease need less treatment duration, dosage, and maintenance use of prednisone. In all case series (Citation25,Citation34,Citation40,Citation142–144) over 80% of the patients showed improvement in the reported outcome measures.

Sarcoidosis (Sar)

We included two case studies (from 1977 and 1995) comprising 38 patients in total (Citation145,Citation146). Efficacy was assessed by counting the number of patients that were responders (n = 16) or showed clearing of skin lesions (n = 12).

Systemic sclerosis (SS)

We included four studies, i.e. one cohort study (Citation147), one prospective case series (Citation148), and two RCTs (Citation149,Citation150) comprising 150 patients in total. Van den Hoogen et al. (Citation149) performed a double-blind-RCT (Table S12. GRADE evidence profile), enrolling 29 patients: 17 received intramuscular MTX and 12 received placebo. The response to treatment was evaluated by a self-made set of criteria; the total skin score (TSS), the VAS of general well-being (0–100), lung diffusion capacity (DLco), and presence or absence of digital ulcerations. Van den Hoogen et al. reported that a significantly larger number of patients receiving MTX [n = 8 (53%)] who completed the first 24 weeks of the study responded favorably compared to patients receiving placebo [n = 1 (10%), p = .03]. Although the study sample was small, the authors concluded that low-dose MTX seems to be more effective than placebo according to their response criteria.

Pope et al. (Citation150) performed an RCT (Table S12. GRADE evidence profile) that enrolled 71 patients who were randomized to MTX (n = 35) or placebo (n = 36). Efficacy was quantified subjectively by the patient and the physician and objectively by the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) skin score and a modified Rodnan’s skin score. No significant difference was found between the two treatment groups. However, a trend in favor of the MTX treatment was seen in Rodnan skin score, ULCA skin score, DLco, and physician global assessment.

The case series and cohort study involved 98 patients treated with MTX, of which at least half were reported to be responders.

Urticaria (Ur)

We included four studies comprising a total of 77 patients (Citation58,Citation66,Citation151,Citation152). Two studies were RCTs (Citation151,Citation152) and two studies were case series (Citation58,Citation66). Leducq et al. (Citation151) performed a randomized-placebo controlled trial (Table S13. GRADE evidence profile) in which 75 patients were enrolled: 39 patients used MTX and 36 placeboes. Effectiveness was defined as complete remission. In the intention-to-treat analysis, three patients in the MTX group and 0 patients in the placebo group achieved this endpoint at week 18 (p = .24).

Sharma et al. (Citation152) performed a randomized placebo-controlled trial involving 29 patients with H1-antihistaminics resistant urticaria (Table S13. GRADE evidence profile): 14 patients used MTX and 15 patients placebo. Effectiveness was defined as −67.7% on primary outcomes (wheal score, pruritus score, wheal size, wheal duration, wheal episodes, days/week with urticaria). Three-and-a-half of the ten patients (35%) in the MTX group and 3.67 of the seven patients (52%) in the placebo group achieved a 67.7% reduction of the primary outcomes. It is unclear how to interpret this. In the case series, about 75% of the patients responded to MTX.

Vitiligo (Vi)

We included two studies comprising 31 patients in total; one randomized comparative study (Citation37) and one prospective case series (Citation47). Efficacy was assessed in Alghamdi & Khurrum (Citation37) as no change in vitiligo lesions, which occurred in all six patients. Singh et al. (Citation47) performed a prospective randomized open-label study (Table S14. GRADE evidence profile) in which 52 patients were enrolled: 26 were treated with MTX and 26 with oral mini pulse (OMP) corticosteroids. In the MTX group, six of 25 patients developed new vitiligous lesions, compared to seven of 25 patients in the OMP group. The difference was not significant. Both groups showed a similar reduction in the Vitiligo Disease Activity (VIDA) score and the Vitiligo Area Scoring Index (VASI).

Adult Onset Still’s Disease (AoSD), Allergic Contact Eczema (All CE), Erythema Nodosum Leprosum (ENL), Granuloma Annulare (GA), Hand Eczema (HE), Lichen Sclerosis (extragenital) (LS), Lymphomatoid Papulosis (LP), Panniculitis (Pa), Papular Dermatitis (PD), Parthenium Dermatitis (PrD), Pemphigus Foliaceus (PF), Palmoplantar Pompholyx (PPP), Prurigo Nodularis (PN), Prurigo (Pr), Scleredema Diabetoricum (SD), Scleroderma (Scl).

For each of these diseases we included only one (Citation23,Citation24,Citation53,Citation72,Citation73,Citation153–162) or two (Citation163,Citation164) case series. These studies all had small sample sizes and very low quality of evidence. The study from Kalyoncu (Citation153) with adult-onset Still’s Disease enrolled 202 patients who received MTX; the study from Patel (Citation154) enrolled 32 patients with allergic contact eczema and the study from Politiek (Citation156) enrolled 42 patients with hand eczema. The details of these studies are shown in Tables S1, S2.

Safety

The majority of the studies reported AEs and some studies reported SAEs as well. Most commonly reported AEs involved gastrointestinal complaints, such as nausea, vomiting or diarrhea, and elevation of liver enzymes. Details on all AEs can be found in Table S2. The following SAEs were reported: a serious pyelonephritis needing hospitalization (Citation62), a viral-induced exacerbation of asthma needing hospitalization (Citation62), bullous impetigo (Citation86), chest tightness/wheezing (Citation86), hospitalization for community acquired pneumonia (Citation86), post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis (Citation86), cholera (Citation88), exacerbations of AD (Citation43,Citation88), myocardial infarction (Citation88), respiratory problems (Citation88), hospitalization for social reasons after trauma (Citation88), hospitalization because of psychiatric comorbidity (Citation43), folliculitis (Citation95), herpetic recurrences (Citation95), six mortalities (one MTX related due to respiratory tract infection in a setting of MTX-related pancytopenia, other unknown) (Citation99), herpes encephalitis (Citation28), pancytopenia (Citation28), urothelial carcinoma (Citation28), dermohypodermitis (Citation105), paronychia (Citation105), elevation of liver enzymes (Citation27), dehydration/gastroenteritis (Citation130), death by bronchopneumonia (Citation23), leukopenia requiring hospitalization (Citation145), renal crisis (Citation149), sudden death (Citation149), cerebrovascular stroke (Citation151), and unstable angina (Citation151). In total 17 SAEs reported with an unknown origin were reported (Citation143,Citation150).

Quality

Most evidence was of very low quality. We found outcomes of low quality for only t diseases (dermatomyositis, morphea, and systemic sclerosis). All GRADE ratings are shown in Tables S3–S14.

Discussion

This SR provides a new overview of the available literature for the off-label use of MTX in dermatology. This overview was updated in comparison to the BAD guideline (Citation15) and two earlier reviews (Citation13,Citation14) and used GRADE to rate the quality of evidence of the included RCTs. It is intended as a basis for off-label MTX guidance in dermatology to ensure optimal off-label prescription in daily practice and can contribute to the development of a research agenda concerning the use of MTX in dermatology.

Conclusions and perspectives

The quality of the evidence included in this SR varied. For systemic sclerosis (Citation150), dermatomyositis (Citation105), and morphea (Citation51), we found evidence of low quality. Most evidence was found for the treatment of atopic dermatitis with MTX, which therefore appears to be a treatment option in both adults and children with AD. For other diseases, we found only very low-quality evidence. The main reason for the lack of high-quality evidence is that only 14 RCTs on dermatological off-label MTX prescriptions were found. Most other evidence involved poor-quality retrospective case series or cohort studies. In the GRADE system (Citation16) these types of studies all start with very low quality. Furthermore, they had very small sample sizes and were heterogeneous in their study characteristics, outcomes, and outcome measures. The absence of the reported AEs and SAEs in some studies could contribute to the lack of evidence regarding safety on off-label use of MTX.

The MTX dosages used in the included studies ranged widely, from 0.2 mg/kg daily up to 37.5 mg weekly. It is debatable whether the higher dosages are necessary for treating dermatological diseases. The European Dermatology Forum (EDF) guideline for psoriasis, however, recommends higher dosages: 15 mg to a maximum of 25 mg weekly (Citation165). The EDF guideline recommends using folic acid during treatment with MTX, which was done in 47 of the included studies. They also recommend administering MTX subcutaneously for psoriasis. In many of the included studies in our SR, MTX was given orally instead.

The maximum reported treatment duration was 132 months. The EDF guideline does not have a recommendation on treatment duration. In a rheumatology guideline, however, Visser et al. suggest that long-term MTX treatment is safe (Citation166). The adverse events that were most commonly reported were gastrointestinal complaints like nausea, vomiting or diarrhea, and elevation of liver enzymes. This corresponds with the important side effects reported during the treatment of psoriasis.

Strengths and limitations

Our SR highlights the lack of high-quality evidence for the off-label use of MTX in dermatology and specifies the current knowledge gaps, which can give direction to future research.

Several limitations should also be mentioned. First, as with any literature review, there is a risk of publication bias because negative results are usually not published. Second, the outcomes used in the included studies were very heterogeneous, which made comparisons and pooling impossible. Third, many studies used poorly defined outcomes, such as ‘treatment response.’ We nevertheless decided to include these studies to provide a complete overview of the current literature.

Several studies on the efficacy of MTX are ongoing according to ClinicalTrials.gov; those studies involve skin diseases, such as vitiligo, bullous pemphigoid, Takayasu arteritis, granulomatosis with polyangiitis, giant cell arteritis, and erythema nodosum leprosum. As the results of these studies were not yet published, they were not included in this SR. Therefore, we suggest that this SR should be updated frequently or evolve into a living SR (Citation167).

Despite the emergence of newer drugs like biologics, we believe that MTX still has a role in the treatment of dermatological diseases due to its low price, wide availability, and extensive experience with the drug in this specialism. High-quality evidence for MTX for different dermatosis is needed, and accompanying up-to-date guidelines are of great importance (Citation168). As physicians are ethically required to discuss off-label prescriptions with their patients, Shared Decision Making is also important when prescribing this type of treatment. In Shared Decision Making, physicians and patients decide together which treatment is the best option for the patient and base their decision on the best available evidence and the values and preferences of patients (Citation169).

To optimize the evidence for off-label use of MTX in dermatology, we need high-quality studies in which well-characterized patients are treated with standardized treatments regimens using well-validated outcomes that are relevant to patients and physicians. Ideally, core outcome sets should be used. Negative study results should also be published, especially those showing the ineffectiveness or lack of safety of the drug for certain diseases.

There is a need for harmonization of MTX dosages, how to screen for and monitor during methotrexate use, and for outcome measures used in various studies. Long-term data and safety data are also lacking.

Besides prospective RCTs which for many less frequent dermatoses should be performed by clinical trial networks, prospective cohort studies of cases in clinical practice with a clear case definition or diagnostic criteria, severity measures and patient-reported outcomes could help to improve the quality of the evidence. An example of this type of study is the international TREAT (TREating ATopic dermatitis) Registry Taskforce, which registers the use, effectiveness, and safety of systemic therapies (including MTX) in patients with atopic dermatitis (Citation170). Such studies are needed to improve the quality of care for patients for whom off-label use of MTX is prescribed.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (1.6 MB)Acknowledgments

We thank M. W. Langendam, Ph.D., and C.E.J.M. Limpens, Ph.D. from the Amsterdam UMC for their contribution to this article. We also thank the Off-Label Working Group of the Dutch Society of Dermatology and Venereology (Nederlandse Vereniging voor Dermatologie en Venereologie, NVDV).

Disclosure statement

Drs. van Huizen, Dr. Vermeulen, Drs. Bik, Dr. Borgonjen, Drs. Karsch, Drs. Kuin, and Dr. Gerbens have nothing to disclose. Prof. Dr. Ph.I. Spuls has done consultancies in the past for Sanofi 111017 and AbbVie 041217 (unpaid), was the principal investigator of the MAcAD RCTs (Citation43,Citation44,Citation88), receives departmental independent research grants for TREAT NL registry, for which she is Chief Investigator (CI), from pharma companies since December 2019, is involved in performing clinical trials with many pharmaceutical industries that manufacture drugs used for the treatment of e.g. psoriasis and atopic dermatitis, for which financial compensation is paid to the department/hospital and is one of the main investigator of the SECURE-AD registry.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Franca K, Litewka S. Controversies in off-label prescriptions in dermatology: the perspective of the patient, the physician, and the pharmaceutical companies. Int J Dermatol. 2019;58(7):788–794.

- Picard D, Carvalho P, Bonnavia C, et al. Assessment off-label prescribing in dermatology. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2003;130(5):507–510.

- Sugarman JH, Fleischer AB Jr., Feldman SR. Off-label prescribing in the treatment of dermatologic disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47(2):217–223.

- Aronson JK, Ferner RE. Unlicensed and off-label uses of medicines: definitions and clarification of terminology. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2017;83(12):2615–2625.

- Schram ME, Borgonjen RJ, Bik CM, et al. Off-label use of azathioprine in dermatology: a systematic review. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147(4):474–488.

- Ghaoui N, Hanna E, Abbas O, et al. Update on the use of dapsone in dermatology. Int J Dermatol. 2020;59(7):787–795.

- Vermeulen FM, Gerbens LAA, Schmitt J, et al. The European TREatment of ATopic eczema (TREAT) Registry Taskforce survey: prescribing practices in Europe for phototherapy and systemic therapy in adult patients with moderate-to-severe atopic eczema. Br J Dermatol. 2020;183(6):1073–1082.

- Sidbury R, Davis DM, Cohen DE, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: section 3. Management and treatment with phototherapy and systemic agents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71(2):327–349.

- Sidbury R, Kodama S. Atopic dermatitis guidelines: diagnosis, systemic therapy, and adjunctive care. Clin Dermatol. 2018;36(5):648–652.

- Weda M, Hoebert J, Vervloet M, et al. Study on off-label use of medicinal products in the European Union. Directorate-General for Health and Food Safety (European Commission); 2017. Available from: https://ec.europa.eu/health/sites/default/files/files/documents/2017_02_28_final_study_report_on_off-label_use_.pdf.

- Geneesmiddelenwet artikel 68; 2007 [cited 2021 Jun 3]. Available from: https://wetten.overheid.nl/jci1.3:c.:BWBR0021505&hoofdstuk=6&artikel=68&z=2020-04-01&g=2020-04-01

- Bieber T, Straeter B. Off-label prescriptions for atopic dermatitis in Europe. Allergy. 2015;70(1):6–11.

- Shen S, O'Brien T, Yap LM, et al. The use of methotrexate in dermatology: a review. Australas J Dermatol. 2012;53(1):1–18.

- Diani M, Grasso V, Altomare G. Methotrexate: practical use in dermatology. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2016;151(5):535–543.

- Warren RB, Weatherhead SC, Smith CH, et al. British association of dermatologists' guidelines for the safe and effective prescribing of methotrexate for skin disease 2016.[erratum appears in Br J Dermatol. 2017 jun;176(6):1678; PMID: 28581246]. Br J Dermatol. 2016;175(1):23–44.

- Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, GRADE Working Group, et al. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 2008;336(7650):924–926.

- NHS. PROSPERO – International prospective register of systematic reviews; 2017 [cited 2021 Apr 19]. Available from: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/

- Criteria for applying or using GRADE; 2016 [cited 2021 Jun 3]. Available from: https://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/docs/Criteria_for_using_GRADE_2016-04-05.pdf

- Guyatt G, Oxman A, Akl E, et al. GRADE guidelines: 1. Introduction-GRADE evidence profiles and summary of findings tables. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(4):383–394.

- Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2021;10(1):89.

- Downham TF, Chapel TA. Bullous pemphigoid: therapy in patients with and without diabetes mellitus. Arch Dermatol. 1978;114(11):1639–1642.

- Ho V, Dutz J. Methotrexate–The value of case series for older drugs. J Cutan Med Surg. 2018;22(5):537.

- Rivitti EA, Camargo ME, Castro RM, et al. Use of methotrexate to treat pemphigus foliaceus. Int J Dermatol. 1973;12(2):119–122.

- Egan CA, Rallis TM, Meadows KP, et al. Low-dose oral methotrexate treatment for recalcitrant palmoplantar pompholyx. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;40(4):612–614.

- Peck SM, Osserman KE, Samuels AJ, et al. Studies in bullous diseases. Treatment of pemphigus vulgaris with immunosuppressives (steroids and methotrexate) and leucovorin calcium. Arch Dermatol. 1971;103(2):141–147.

- Kasteler JS, Callen JP. Low-dose methotrexate administered weekly is an effective corticosteroid-sparing agent for the treatment of the cutaneous manifestations of dermatomyositis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;36(1):67–71.

- Lajevardi V, Ghodsi SZ, Hallaji Z, et al. Treatment of erosive oral lichen planus with methotrexate. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2016;14(3):286–293.

- Hornung T, Ko A, Tuting T, et al. Efficacy of low-dose methotrexate in the treatment of dermatomyositis skin lesions. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2012;37(2):139–142.

- Goujon C, Viguier M, Staumont-Salle D, et al. Methotrexate versus cyclosporine in adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: a phase III randomized noninferiority trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2017;2(6):562–569.e3.

- Torok KS, Arkachaisri T. Methotrexate and corticosteroids in the treatment of localized scleroderma: a standardized prospective longitudinal single-center study. J Rheumatol. 2012;39(2):286–294.

- Shah N, Alhusayen R, Walsh S, et al. Methotrexate in the treatment of moderate to severe atopic dermatitis: a retrospective study. J Cutan Med Surg. 2018;22(5):484–487.

- Malekzad F, Saeedi M, Ayatollahi A. Low dose methotrexate for the treatment of generalized lichen planus. Iran J Dermatol. 2012;14(58):131–135.

- Boehm IB, Boehm GA, Bauer R. Management of cutaneous lupus erythematosus with low-dose methotrexate: indication for modulation of inflammatory mechanisms. Rheumatol Int. 1998;18(2):59–62.

- Baum S, Greenberger S, Samuelov L, et al. Methotrexate is an effective and safe adjuvant therapy for pemphigus vulgaris. Eur J Dermatol. 2012;22(1):83–87.

- Christen-Zaech S, Hakim MD, Afsar FS, et al. Pediatric morphea (localized scleroderma): review of 136 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59(3):385–396.

- Kwatra SG, Jorizzo JL. Bullous pemphigoid: a case series with emphasis on long-term remission off therapy. J Dermatolog Treat. 2013;24(5):327–331.

- AlGhamdi K, Khurrum H. Methotrexate for the treatment of generalized vitiligo. Saudi Pharm J. 2013;21(4):423–424.

- Kanwar AJ, De D. Methotrexate for treatment of lichen planus: old drug, new indication. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27(3):e410–e413.

- Ilyas S, Inayat S, Khurshid K, et al. Efficacy and safety of methotrexate in lichen planus. J Pak Assoc Dermatol. 2016;26(1):41–47.

- Tran KD, Wolverton JE, Soter NA. Methotrexate in the treatment of pemphigus vulgaris: experience in 23 patients. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169(4):916–921.

- Koch SB, Cerci FB, Jorizzo JL, et al. Linear morphea: a case series with long-term follow-up of young, methotrexate-treated patients. J Dermatolog Treat. 2013;24(6):435–438.

- Shahidi-Dadras M, Abdollahimajd F, Jahangard R, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging evaluation in patients with linear morphea treated with methotrexate and high-dose corticosteroid. Dermatol Res Pract. 2018;2018:8391218.

- Roekevisch E, Schram ME, Leeflang MMG, et al. Methotrexate versus azathioprine in patients with atopic dermatitis: 2-year follow-up data. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018;141(2):825–827.e10.

- Schram ME, Roekevisch E, Leeflang MM, et al. A randomized trial of methotrexate versus azathioprine for severe atopic eczema. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128(2):353–359.

- Mertens JS, Zweers MC, Kievit W, et al. High-dose intravenous pulse methotrexate in patients with eosinophilic fasciitis. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152(11):1262–1265.

- Roberts H, Orchard D. Methotrexate is a safe and effective treatment for paediatric discoid (nummular) eczema: a case series of 25 children. Australas J Dermatol. 2010;51(2):128–130.

- Singh H, Kumaran MS, Bains A, et al. A randomized comparative study of oral corticosteroid minipulse and low-dose oral methotrexate in the treatment of unstable vitiligo. Dermatology. 2015;231(3):286–290.

- Bakker CV, Terra JB, Pas HH, et al. Bullous pemphigoid as pruritus in the elderly: a common presentation. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149(8):950–953.

- Tetart F, Joly P. Low doses of methotrexate for the treatment of chronic eczema in the elderly. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25(11):1364–1365.

- Platsidaki E, Tzanetakou V, Kouris A, et al. Methotrexate: an effective monotherapy for refractory generalized morphea. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2017;10:165–169.

- Zulian F, Martini G, Vallongo C, et al. Methotrexate treatment in juvenile localized scleroderma: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63(7):1998–2006.

- Purvis D, Lee M, Agnew K, et al. Long-term effect of methotrexate for childhood atopic dermatitis. J Paediatr Child Health. 2019;55(12):1487–1491.

- Naka F, Strober BE. Methotrexate treatment of generalized granuloma annulare: a retrospective case series. J Dermatolog Treat. 2018;29(7):720–724.

- Gansauge S, Breitbart A, Rinaldi N, et al. Methotrexate in patients with moderate systemic lupus erythematosus (exclusion of renal and central nervous system disease). Ann Rheum Dis. 1997;56(6):382–385.

- Lyakhovitsky A, Barzilai A, Heyman R, et al. Low-dose methotrexate treatment for moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis in adults. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010;24(1):43–49.

- Zulian F, Vallongo C, Patrizi A, et al. A long-term follow-up study of methotrexate in juvenile localized scleroderma (morphea). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67(6):1151–1156.

- Knopfel N, Noguera-Morel L, Hernandez-Martin A, et al. Methotrexate for severe nummular eczema in children: efficacy and tolerability in a retrospective study of 28 patients. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35(5):611–615.

- Sagi L, Solomon M, Baum S, et al. Evidence for methotrexate as a useful treatment for steroid-dependent chronic urticaria. Acta Derm Venereol. 2011;91(3):303–306.

- Lucas P, Bodemer C, Barbarot S, et al. Methotrexate in severe childhood alopecia areata: long-term follow-up. Acta Derm Venereol. 2016;96(1):102–103.

- Droitcourt C, Milpied B, Ezzedine K, et al. Interest of high-dose pulse corticosteroid therapy combined with methotrexate for severe alopecia areata: a retrospective case series. Dermatology. 2012;224(4):369–373.

- Cox D, O'Regan G, Collins S, et al. Juvenile localized scleroderma: a retrospective review of respons to systemic treatment. Iran J Med Sci. 2008;177(4):343–346.

- Deo M, Yung A, Hill S, et al. Methotrexate for treatment of atopic dermatitis in children and adolescents. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53(8):1037–1041.

- Heilborn JD, Stahle-Backdahl M, Albertioni F, et al. Low-dose oral pulse methotrexate as monotherapy in elderly patients with bullous pemphigoid. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;40(5 Pt 1):741–749.

- El-Khalawany MA, Hassan H, Shaaban D, et al. Methotrexate versus cyclosporine in the treatment of severe atopic dermatitis in children: a multicenter experience from Egypt. Eur J Pediatr. 2013;172(3):351–356.

- Mertens JS, van den Reek JM, Kievit W, et al. Drug survival and predictors of drug survival for methotrexate treatment in a retrospective cohort of adult patients with localized scleroderma. Acta Derm Venereol. 2016;96(7):943–947.

- Perez A, Woods A, Grattan CE. Methotrexate: a useful steroid-sparing agent in recalcitrant chronic urticaria. Br J Dermatol. 2010;162(1):191–194.

- Fitch PG, Rettig P, Burnham JM, et al. Treatment of pediatric localized scleroderma with methotrexate. J Rheumatol. 2006;33(3):609–614.

- Lim SK, Lim CA, Kwon IS, et al. Low-Dose systemic methotrexate therapy for recalcitrant alopecia areata. Ann Dermatol. 2017;29(3):263–267.

- Rattanakaemakorn P, Jorizzo JL. The efficacy of methotrexate in the treatment of en coup de sabre (linear morphea subtype). J Dermatolog Treat. 2017;29:197–199.

- Zoller L, Ramon M, Bergman R. Low dose methotrexate therapy is effective in late-onset atopic dermatitis and idiopathic eczema. Isr Med Assoc J. 2008;10(6):413–414.

- Kroft EB, Creemers MC, van den Hoogen FH, et al. Effectiveness, side-effects and period of remission after treatment with methotrexate in localized scleroderma and related sclerotic skin diseases: an inception cohort study. Br J Dermatol. 2009;160(5):1075–1082.

- Schanz S, Henes J, Ulmer A, et al. Response evaluation of musculoskeletal involvement in patients with deep morphea treated with methotrexate and prednisolone: a combined MRI and clinical approach. Am J Roentgenol. 2013;200(4):W376–W382.

- Breuckmann F, Appelhans C, Harati A, et al. Failure of low-dose methotrexate in the treatment of scleredema diabeticorum in seven cases. Dermatology. 2005;211(3):299–301.

- Chartaux E, Joly P. [Long-term follow-up of the efficacy of methotrexate alone or in combination with low doses of oral corticosteroids in the treatment of alopecia areata totalis or universalis]. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2010;137(8–9):507–513.

- Hammerschmidt M, Brenner FM. Efficacy and safety of methotrexate in alopecia areata. An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89(5):729–734.

- Thi Van AT, Lan AT, Anh MH, et al. Efficacy and safety of methotrexate in combination with mini pulse doses of methylprednisolone in severe alopecia areata. The Vietnamese experience. Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 2019;7(2):200–203.

- Alkeraye S, Becquart C, Delaporte E, et al. Efficacy of combining pulse corticotherapy and methotrexate in alopecia areata: real-life evaluation. J Dermatol. 2017;44(12):e319–e320.

- Anuset D, Perceau G, Bernard P, et al. Efficacy and safety of methotrexate combined with low- to moderate-dose corticosteroids for severe alopecia areata. Dermatology. 2016;232(2):242–248.

- Chong JH, Taieb A, Morice-Picard F, et al. High-dose pulsed corticosteroid therapy combined with methotrexate for severe alopecia areata of childhood. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31(11):e476–e477.

- Firooz AR, Fouladi DF. Methotrexate plus prednisolone in severe alopecia areata. Am J Drug Discov Dev. 2013;3(3):188–193.

- Joly P. The use of methotrexate alone or in combination with low doses of oral corticosteroids in the treatment of alopecia totalis or universalis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55(4):632–636.

- Landis ET, Pichardo-Geisinger RO. Methotrexate for the treatment of pediatric alopecia areata. J Dermatolog Treat. 2017;29:145–148.

- Royer M, Bodemer C, Vabres P, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of methotrexate in severe childhood alopecia areata. Br J Dermatol. 2011;165(2):407–410.

- Vano-Galvan S, Fernandez-Crehuet P, Grimalt R, et al. Alopecia areata totalis and universalis: a multicenter review of 132 patients in Spain. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31(3):550–556.

- Hegazy S, Tauber M, Bulai-Livideanu C, et al. Systemic treatment of severe adult atopic dermatitis in clinical practice: analysis of prescribing pattern in a cohort of 241 patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31(9):e423–e4.

- Dvorakova V, O'Regan GM, Irvine AD. Methotrexate for severe childhood atopic dermatitis: clinical experience in a tertiary center. Pediatr Dermatol. 2017;34(5):528–534.

- Anderson K, Putterman E, Rogers RS, et al. Treatment of severe pediatric atopic dermatitis with methotrexate: a retrospective review. Pediatr Dermatol. 2019;36(3):298–302.

- Gerbens LAA, Hamann SAS, Brouwer MWD, et al. Methotrexate and azathioprine for severe atopic dermatitis: a 5-year follow-up study of a randomized controlled trial. Br J Dermatol. 2018;178(6):1288–1296.

- Weatherhead SC, Wahie S, Reynolds NJ, et al. An open-label, dose-ranging study of methotrexate for moderate-to-severe adult atopic eczema. Br J Dermatol. 2007;156(2):346–351.

- Taieb Y, Baum S, Ben Amitai D, et al. The use of methotrexate for treating childhood atopic dermatitis: a multicenter retrospective study. J Dermatolog Treat. 2019;30(3):240–244.

- Rahman SI, Siegfried E, Flanagan KH, et al. The methotrexate polyglutamate assay supports the efficacy of methotrexate for severe inflammatory skin disease in children. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70(2):252–256.

- Syed AR, Aman S, Nadeem M, et al. The efficacy and safety of oral methotrexate in chronic eczema. J Pak Assoc Dermatol. 2009;19(4):220–224.

- Mittal A, Khare A, Gupta L, et al. Use of methotrexate in recalcitrant eczema. Indian J Dermatol. 2011;56(2):232.

- Goujon C, Berard F, Dahel K, et al. Methotrexate for the treatment of adult atopic dermatitis. Eur J Dermatol. 2006;16(2):155–158.

- Vedie AL, Ezzedine K, Amazan E, et al. Long-term use of systemic treatments for moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis in adults: a monocentric retrospective study. Acta Derm Venereol. 2016;96(6):802–806.

- Delcasso B, Goujon C, Hacard F, et al. Tolerance of methotrexate in a daily practice cohort of adults with atopic dermatitis. Eur J Dermatol. 2018;28(2):266–267.

- Baum S, Porat S, Lyakhovitsky A, et al. Adult atopic dermatitis in hospitalized patients: comparison between those with childhood-onset and late-onset disease. Dermatology. 2019;235(5):365–371.

- Politiek K, van der Schaft J, Coenraads PJ, et al. Drug survival for methotrexate in a daily practice cohort of adult patients with severe atopic dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. 2016;174(1):201–203.

- Du-Thanh A, Merlet S, Maillard H, et al. Combined treatment with low-dose methotrexate and initial short-term superpotent topical steroids in bullous pemphigoid: an open, multicentre, retrospective study. Br J Dermatol. 2011;165(6):1337–1343.

- Bara C, Maillard H, Briand N, et al. Methotrexate for bullous pemphigoid: preliminary study. Arch Dermatol. 2003;139(11):1506–1507.

- Dereure O, Bessis D, Guillot B, et al. Treatment of bullous pemphigoid by low-dose methotrexate associated with short-term potent topical steroids: an open prospective study of 18 cases. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138(9):1255–1256.

- Kjellman P, Eriksson H, Berg P. A retrospective analysis of patients with bullous pemphigoid treated with methotrexate. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144(5):612–616.

- Kremer N, Zeeli T, Sprecher E, et al. Failure of initial disease control in bullous pemphigoid: a retrospective study of hospitalized patients in a single tertiary center. Int J Dermatol. 2017;56(10):1010–1016.

- Paul MA, Jorizzo JL, Fleischer AB, Jr, et al. Low-dose methotrexate treatment in elderly patients with bullous pemphigoid. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31(4):620–625.

- Ruperto N, Pistorio A, Oliveira S, et al. Prednisone versus prednisone plus ciclosporin versus prednisone plus methotrexate in new-onset juvenile dermatomyositis: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2016;387(10019):671–678.

- Ramanan A-W,N, Ota S, Parker S, et al. The effectiveness of treating juvenile dermatomyositis with methotrexate and aggressively tapered corticosteroids. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52(11):3570–3578.

- Click JW, Qureshi AA, Vleugels RA. Methotrexate for the treatment of cutaneous dermatomyositis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68(6):1043–1045.

- Zieglschmid-Adams M, Pandya A, Cohen S, et al. Treatment of dermatomyositis with methotrexate. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32(5 Pt 1):754–757.

- Chen KS, Tan TH, Yesudian PD. Clinical, demographic and laboratory characteristics of methotrexate-responsive eczema. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30(11):e158–e159.

- Shaffrali FC, Colver GB, Messenger AG, et al. Experience with low-dose methotrexate for the treatment of eczema in the elderly. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48(3):417–419.

- Berianu F, Cohen MD, Abril A, et al. Eosinophilic fasciitis: clinical characteristics and response to methotrexate. Int J Rheum Dis. 2015;18(1):91–98.

- Lebeaux D, Frances C, Barete S, et al. Eosinophilic fasciitis (Shulman disease): new insights into the therapeutic management from a series of 34 patients. Rheumatology. 2012;51(3):557–561.

- Carneiro JR, Sato EI. Double blind, randomized, placebo controlled clinical trial of methotrexate in systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol. 1999;26(6):1275–1279.

- Islam MN, Hossain M, Haq SA, et al. Efficacy and safety of methotrexate in articular and cutaneous manifestations of systemic lupus erythematosus. Int J Rheum Dis. 2012;15(1):62–68.

- Arfi S, Numeric P, Grollier L, et al. [Treatment of corticodependent systemic lupus erythematosus with low-dose methotrexate]. Rev Med Intern. 1995;16(12):885–890.

- Boehm I. Decrease of B-cells and autoantibodies after low-dose methotrexate. Biomed Pharmacother. 2003;57(7):278–281.

- Fruchter R, Kurtzman DJB, Patel M, et al. Characteristics and alternative treatment outcomes of antimalarial-refractory cutaneous lupus erythematosus. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153(9):937–939.

- Kan H, Nagar S, Patel J, et al. Longitudinal treatment patterns and associated outcomes in patients with newly diagnosed systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin Ther. 2016;38(3):610–624.

- Wenzel J, Brahler S, Bauer R, et al. Efficacy and safety of methotrexate in recalcitrant cutaneous lupus erythematosus: results of a retrospective study in 43 patients. Br J Dermatol. 2005;153(1):157–162.

- Chauhan P, De D, Handa S, et al. A prospective observational study to compare efficacy of topical triamcinolone acetonide 0.1% oral paste, oral methotrexate, and a combination of topical triamcinolone acetonide 0.1% and oral methotrexate in moderate to severe oral lichen planus. Dermatol Ther. 2018;31(1):e12563.

- Torti DC, Jorizzo JL, McCarty MA. Oral lichen planus: a case series with emphasis on therapy. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143(4):511–515.

- Turan H, Baskan EB, Tunali S, et al. Methotrexate for the treatment of generalized lichen planus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60(1):164–166.

- Kortekangas-Savolainen O, Kiilholma P. Treatment of vulvovaginal erosive and stenosing lichen planus by surgical dilatation and methotrexate. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2007;86(3):339–343.

- Babahosseini H, Tavakolpour S, Mahmoudi H, et al. Lichen planopilaris: retrospective study on the characteristics and treatment of 291 patients. J Dermatolog Treat. 2019;30(6):598–604.

- Bulbul Baskan E, Yazici S. Treatment of lichen planopilaris: methotrexate or cyclosporine a therapy? Cutan Ocul Toxicol. 2018;37(2):196–194.

- Kerkemeyer KLS, Green J. Lichen planopilaris: a retrospective study of 32 cases in an Australian tertiary referral hair clinic. Australas J Dermatol. 2018;59(4):297–301.

- Bakhtiar R, Noor SM, Paracha MM. Effectiveness of oral methotrexate therapy versus systemic corticosteroid therapy in treatment of generalised lichen planus. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2018;28(7):505–508.

- Naeini FF, Saber M, Asilian A, et al. Clinical efficacy and safety of methotrexate versus hydroxychloroquine in preventing lichen planopilaris progress: a randomized clinical trial. Int J Prev Med. 2017;8(37):37.

- Bulur I, Erdoğan HK, Karapınar T, et al. Morphea in Middle Anatolia, Turkey: a 5-year single-center experience. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2017;34(4):334–338.

- Li SC, Torok KS, Rabinovich CE, et al. Initial results from a pilot comparative effectiveness study of three methotrexate-based consensus treatment plans for juvenile localized scleroderma. J Rheumatol. 2020;47:1242–1252.

- Mirsky L, Chakkittakandiyil A, Laxer RM, et al. Relapse after systemic treatment in paediatric morphoea. Br J Dermatol. 2012;166(2):443–445.

- Piram M, McCuaig CC, Saint-Cyr C, et al. Short- and long-term outcome of linear morphoea in children. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169(6):1265–1271.

- Uziel Y, Feldman BM, Krafchik BR, et al. Methotrexate and corticosteroid therapy for pediatric localized scleroderma. J Pediatr. 2000;136(1):91–95.

- Weibel L, Sampaio MC, Visentin MT, et al. Evaluation of methotrexate and corticosteroids for the treatment of localized scleroderma (morphoea) in children. Br J Dermatol. 2006;155(5):1013–1020.

- Kreuter A, Gambichler T, Breuckmann F, et al. Pulsed high-dose corticosteroids combined with low-dose methotrexate in severe localized scleroderma. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141(7):847–852.

- Seyger MM, van den Hoogen FH, de Boo T, et al. Low-dose methotrexate in the treatment of widespread morphea. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39(2):220–225.

- Wlodek C, Korendowych E, McHugh N, et al. Morphoea profunda and its relationship to eosinophilic fasciitis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2018;43(3):306–310.

- Allison DS, El-Azhary RA, Calobrisi SD, et al. Pityriasis rubra pilaris in children. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47(3):386–389.

- Chapalain V, Beylot-Barry M, Doutre MS, et al. Treatment of pityriasis rubra pilaris: a retrospective study of 14 patients. J Dermatolog Treat. 1999;10(2):113–117.

- Dicken CH. Treatment of classic pityriasis rubra pilaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31(6):997–999.

- Knowles WR, Chernosky ME. Pityriasis rubra pilaris. Prolonged treatment with methotrexate. Arch Dermatol. 1970;102(6):603–612.

- Lever WF. Methotrexate and prednisone in pemphigus vulgaris. Therapeutic results obtained in 36 patients between 1961 and 1970. Arch Dermatol. 1972;106(4):491–497.

- Mashkilleyson N, Mashkilleyson AL. Mucous membrane manifestations of pemphigus vulgaris. A 25-year survey of 185 patients treated with corticosteroids or with combination of corticosteroids with methotrexate or heparin. Acta Derm Venereol. 1988;68(5):413–421.

- Smith TJ, Bystryn JC. Methotrexate as an adjuvant treatment for pemphigus vulgaris. Arch Dermatol. 1999;135(10):1275–1276.

- Lower EE, Baughman RP. Prolonged use of methotrexate for sarcoidosis. Arch Intern Med. 1995;155(8):846–851.

- Veien NK, Brodthagen H. Cutaneous sarcoidosis treated with methotrexate. Br J Dermatol. 1977;97(2):213–216.

- Herrick AL, Pan X, Peytrignet S, et al. Treatment outcome in early diffuse cutaneous systemic sclerosis: the European Scleroderma Observational Study (ESOS). Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76(7):1207–1218.

- Sumanth M, Sharma VK, Khaitan BK, et al. Evaluation of oral methotrexate in the treatment of systemic sclerosis. Int J Dermatol. 2007;46(2):218–223.

- van den Hoogen FH, Boerbooms AM, Swaak AJ, et al. Comparison of methotrexate with placebo in the treatment of systemic sclerosis: a 24 week randomized double-blind trial, followed by a 24 week observational trial. Br J Rheumatol. 1996;35(4):364–372.

- Pope JE, Bellamy N, Seibold JR, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of methotrexate versus placebo in early diffuse scleroderma. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44(6):1351–1358.

- Leducq S, Samimi M, Bernier C, et al. Efficacy and safety of methotrexate add-on therapy versus placebo for patients with chronic spontaneous urticaria resistant to H1-antihistamines: a randomized, controlled trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:240–243.

- Sharma VK, Singh S, Ramam M, et al. A randomized placebo-controlled double-blind pilot study of methotrexate in the treatment of H1 antihistamine-resistant chronic spontaneous urticaria. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2014;80(2):122–128.

- Kalyoncu U, Solmaz D, Emmungil H, et al. Response rate of initial conventional treatments, disease course, and related factors of patients with adult-onset still's disease: data from a large multicenter cohort. J Autoimmun. 2016;69:59–63.

- Patel A, Burns E, Burkemper NM. Methotrexate use in allergic contact dermatitis: a retrospective study. Contact Dermatitis. 2018;78(3):194–198.

- Hossain D. Using methotrexate to treat patients with ENL unresponsive to steroids and clofazimine: a report on 9 patients. Lepr Rev. 2013;84(1):105–112.

- Politiek K, van der Schaft J, Christoffers WA, et al. Drug survival of methotrexate treatment in hand eczema patients: results from a retrospective daily practice study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30(8):1405–1407.

- Fernandez-de-Misa R, Hernandez-Machin B, Servitje O, et al. First-line treatment in lymphomatoid papulosis: a retrospective multicentre study. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2018;43(2):137–143.

- Torrelo A, Noguera-Morel L, Hernandez-Martin A, et al. Recurrent lipoatrophic panniculitis of children. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31(3):536–543.

- Moustafa FA, Sandoval LF, Jorizzo JL, et al. Systemic treatment of papular dermatitis: a retrospective study. J Dermatolog Treat. 2015;26(5):431–434.

- Spring P, Gschwind I, Gilliet M. Prurigo nodularis: retrospective study of 13 cases managed with methotrexate. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2014;39(4):468–473.

- Sharma VK, Bhat R, Sethuraman G, et al. Treatment of parthenium dermatitis with methotrexate. Contact Dermatitis. 2007;57(2):118–119.

- Klejtman T, Beylot-Barry M, Joly P, et al. Treatment of prurigo with methotrexate: a multicentre retrospective study of 39 cases. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32(3):437–440.

- Karadag AS, Akdeniz N, Ozlu E, et al. Effect of pulse corticosteroids and low dose methotrexate in cases of treatment-resistant lichen sclerosus. Dermatol Sinica. 2018;36(4):248–249.

- Kreuter A, Tigges C, Gaifullina R, et al. Pulsed high-dose corticosteroids combined with low-dose methotrexate treatment in patients with refractory generalized extragenital lichen sclerosus. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145(11):1303–1308.

- Nast A, Smith CD, Spuls PI, et al. EuroGuiderm guideline for the systemic treatment of psoriasis vulgaris; 2020 [cited 2020 Dec 13]. Available from: https://www.edf.one/dam/jcr:c80dd166-c66f-4548-a7ed-754f5e2687d0/Living_Euroguiderm_guideline_psoriasis_vulgaris.pdf

- Visser K, Katchamart W, Loza E, et al. Multinational evidence-based recommendations for the use of methotrexate in rheumatic disorders with a focus on rheumatoid arthritis: integrating systematic literature research and expert opinion of a broad international panel of rheumatologists in the 3E initiative. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68(7):1086–1093.

- Sbidian E, Chaimani A, Afach S, et al. Systemic pharmacological treatments for chronic plaque psoriasis: a network meta-analysis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;1(1):Cd011535.

- Wilkes M, Johns M. Informed consent and shared decision-making: a requirement to disclose to patients off-label prescriptions. PLOS Med. 2008;5(11):e223.

- Elwyn G, Laitner S, Coulter A, et al. Implementing shared decision making in the NHS. Br Med J. 2010;341:c5146.

- Spuls PI, Gerbens LAA, Apfelbacher CJ, et al. The international TREatment of ATopic eczema (TREAT) registry taskforce: an initiative to harmonize data collection across national atopic eczema photo- and systemic therapy registries. J Invest Dermatol. 2017;137(9):2014–2016.