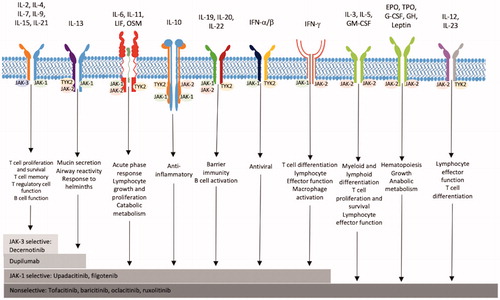

Janus kinases (JAK) are a group of intracellular non-receptor tyrosine kinases involved in the modulation of cytokines which play an integral role in immune and inflammatory processes (Citation1–3). Many autoimmune conditions are precipitated by an imbalance in cytokine function (Citation2). Obstructing this process with JAK inhibiting monoclonal antibodies can be of benefit in the treatment of conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis and inflammatory bowel disease (Citation4). JAK inhibitors repress the signaling of numerous cytokines including IL-4, IL-5, IL-13, IFN-β, and IFN-γ (Citation2,Citation3,Citation5), (). Interferon gamma (IFN-g) has a key role in preventing viral replication which make it important for limiting infection with and preventing reactivation of viruses, such as herpes viruses (Citation6). Other varieties of monoclonal antibodies target fewer components of the inflammatory pathway. For example, dupilumab, used in atopic dermatitis treatment, inhibits only IL-4 and IL-13, allowing for more targeted immune modulation (Citation7). Thus, dupilumab has a decreased risk of serious infection and no increased risk of overall infection (Citation7,Citation8). While widespread cytokine inhibition by JAK inhibitors allows them to be employed for numerous indications, this advantage is balanced with their less specific immune modulatory effect and increased risk of infection (Citation2,Citation8), ().

Figure 1. The widespread inhibition of cytokines by nonselective JAK inhibitors interferes with numerous signaling pathways, as demonstrated above. IFN-β and IFN-γ play key roles in the immune response to viral infections. Suppression of these factors can increase susceptibility to viral infections, such as herpesvirus. Figure adapted from JAK inhibition as a therapeutic strategy for immune and inflammatory diseases (Citation2).

Table 1. JAK inhibitor mechanisms.

JAK inhibitors are associated with an increased risk of herpesvirus infection (Citation9,Citation10). While JAK inhibitors may potentially increase the risk of all herpesviruses due to their modifying effect on the immune system, the literature to-date has largely focused on the risk and incidence of herpes zoster infection in the setting of JAK inhibitor use for an array of autoimmune conditions (Citation11). In the context of rheumatoid arthritis and ulcerative colitis, two of the most common diseases treated with JAK inhibitors, there is an increased risk of herpes zoster during JAK inhibitor therapy (Citation9,Citation10,Citation12,Citation13). The risk of infection associated with JAK inhibitor use and herpes simplex virus 1 and 2 has not been studied as extensively. However, the combined incidences of herpes zoster and herpes simplex virus in rheumatoid arthritis patients treated with tofacitinib was higher than with anti-tumor necrosis factor monoclonal antibodies (Citation14). Patients treated with tofacitinib had crude incidences of 3.87/100 patient-years for herpes zoster and 3.74/100 patient-years for herpes simplex virus, totaling a combined incidence of 7.61/100 patient-years. This was greater than the combined incidence rates for abatacept, rituximab, etanercept, and tocilizumab which ranged from 4.96-6.27/100 patient-years (Citation14). In addition, two case reports have documented herpes simplex virus reactivation in patients on JAK inhibitors, resulting in severe disseminated disease during treatment for myelodysplastic syndrome and rheumatoid arthritis (Citation15,Citation16).

JAK inhibitors are emerging as a treatment for atopic dermatitis, a chronic inflammatory condition of the skin (Citation17,Citation18). Patients with atopic dermatitis have an increased risk of infection due to skin defects, immune dysregulation, predominant staphylococcus aureus colonization, and decreased commensal bacteria of the skin flora (Citation19). The herpesviridae family of viruses are of particular concern, with an increased risk of herpes zoster in patients with severe atopic dermatitis (Citation20). One of the most common and severe microbial infections associated with atopic dermatitis is disseminated infection with herpes simplex virus resulting in eczema herpeticum (Citation21). Instead of being confined to a single area, eczema herpeticum presents with diffuse vesicular rash, fever, and lymphadenopathy (Citation22). Eczema herpeticum occurs in approximately 3% of patients with atopic dermatitis, and this condition has a mortality rate of up to 10% when left untreated or when it occurs in immunocompromised individuals (Citation23–25). An increased risk of herpes virus infections also occurs in patients being treated with JAK inhibitors for atopic dermatitis (Citation26,Citation27). Baricitinib increases the risk of herpes zoster and herpes simplex when used in the treatment of atopic dermatitis (Citation26–29). Although the exact magnitude of the risk is not well characterized, cases of eczema herpeticum have occurred in multiple JAK inhibitor therapy trials (Citation30–33). While JAK inhibitors are highly effective treatments for atopic dermatitis, the increased risk of infection or reactivation of latent disease including herpes virus outbreaks may be of particular importance in this population due to the propensity of patients with severe atopic dermatitis to develop eczema herpeticum (Citation12,Citation34,Citation35). Thus, there may be utility in the preventative use of antivirals during the treatment of atopic dermatitis with JAK inhibitors in order to decrease morbidity and mortality from this condition.

Outbreaks of eczema herpeticum are typically treated with acyclovir or valacyclovir. Valacyclovir is a prodrug of acyclovir that enhances its bioavailability and is rapidly converted to acyclovir when ingested orally (Citation36). Acyclovir is a DNA polymerase inhibitor that treats eczema herpeticum, oral and genital herpes simplex virus infections, and herpes zoster (Citation37). Mild cases of eczema herpeticum can be treated with oral acyclovir or valacyclovir for 7 to 21 days which typically results in an improvement in symptoms and healing of their lesions. Severe cases or outbreaks in those who are significantly immunocompromised receive intravenous acyclovir or valacyclovir until lesions start to crust, after which point they can be transitioned to an oral formulation (Citation38).

In addition to being effective treatment, valacyclovir and acyclovir are safe and well-tolerated drug with no associated toxicities and minimal adverse effects aside from crystalluria and increased creatinine levels (Citation37,Citation39,Citation40). The risk of these side effects can be mitigated with fluid administration prior to taking acyclovir and adjustment in acyclovir dosage according to renal function (Citation41). An ability to prevent reactivation of herpes simplex virus and herpes zoster coupled with this tolerability make valacyclovir and acyclovir options for prophylaxis in patients needing long-term suppression due to severe or recurrent outbreaks or extreme immunosuppression (Citation39,Citation40,Citation42,Citation43). The use of valacyclovir or acyclovir for prophylaxis in patients at risk of eczema herpeticum specifically has not yet been studied. Valacyclovir and acyclovir are equally efficacious in the treatment and prophylaxis of herpes simplex virus, but valacyclovir requires less frequent dosing due to the increased bioavailability (Citation44–46). Twice daily dosing of 500 mg of valacyclovir effectively prevents herpes simplex virus reactivation (Citation47,Citation48). A 15-day supply of this dosage could be obtained for $11 (Citation49). Prophylaxis to prevent eczema herpeticum in patients with atopic dermatitis being treated with a JAK inhibitor may only be needed until clinical improvement occurs (reducing the risk of eczema herpteticum), which may occur in as little as four weeks depending on the agent used and the patient’s response (Citation50).

Given the increased risk of herpes virus infection associated with JAK inhibitor use, the potentially devastating effect a case of eczema herpeticum could have in patients with atopic dermatitis, the effectiveness of acyclovir in preventing herpes simplex virus outbreaks, and the relatively benign side effect profile associated with acyclovir, prophylactic use of acyclovir (or valacyclovir) in patients with atopic dermatitis may be considered when beginning therapy with JAK inhibitors. This may be especially beneficial for patients that already have an established history of herpes simplex virus infection with recurrent and/or severe outbreaks.

Disclosure statement

Dr. Feldman has received research, speaking and/or consulting support from a variety of companies including Galderma, GSK/Stiefel, Almirall, Leo Pharma, Boehringer Ingelheim, Mylan, Celgene, Pfizer, Valeant, Abbvie, Samsung, Janssen, Lilly, Menlo, Merck, Novartis, Regeneron, Sanofi, Novan, Qurient, National Biological Corporation, Caremark, Advance Medical, Sun Pharma, Suncare Research, Informa, UpToDate and National Psoriasis Foundation. He is founder and majority owner of www.DrScore.com and founder and part owner of Causa Research, a company dedicated to enhancing patients’ adherence to treatment. Milaan Shah, Katherine Beuerlein, and Dr. Joseph Jorizzo have no conflicts to disclose.

References

- Furumoto Y, Gadina M. The arrival of JAK inhibitors: advancing the treatment of immune and hematologic disorders. BioDrugs. 2013;27(5):431–438.

- Schwartz DM, Kanno Y, Villarino A, et al. JAK inhibition as a therapeutic strategy for immune and inflammatory diseases. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2017;17(1):78–862.

- Kubo S, Nakayamada S, Sakata K, et al. Janus kinase inhibitor baricitinib modulates human innate and adaptive immune System. Front Immunol. 2018;9:1510.

- O'Shea JJ, Murray PJ. Cytokine signaling modules in inflammatory responses. Immunity. 2008;28(4):477–487.

- Febvre-James M, Lecureur V, Augagneur Y, et al. Repression of interferon β-regulated cytokines by the JAK1/2 inhibitor ruxolitinib in inflammatory human macrophages . Int Immunopharmacol. 2018;54:354–365.

- Liu T, Khanna KM, Carriere BN, et al. Gamma interferon can prevent herpes simplex virus type 1 reactivation from latency in sensory neurons. J Virol. 2001;75(22):11178–11184.

- Kariyawasam HH, James LK, Gane SB. Dupilumab: clinical efficacy of blocking IL-4/IL-13 signalling in chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2020;14:1757–1769.

- Eichenfield LF, Bieber T, Beck LA, et al. Infections in dupilumab clinical trials in atopic dermatitis: a comprehensive pooled analysis. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2019;20(3):443–456.

- Harigai M. Growing evidence of the safety of JAK inhibitors in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford)). 2019;58(Suppl 1):i34–i42.

- Winthrop KL, Curtis JR, Lindsey S, et al. Herpes zoster and tofacitinib: clinical outcomes and the risk of concomitant therapy. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017;69(10):1960–1968.

- Sunzini F, McInnes I, Siebert S. JAK inhibitors and infections risk: focus on herpes zoster. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis. 2020;12:1759720X20936059.

- Colombel JF. Herpes zoster in patients receiving JAK inhibitors for ulcerative colitis: mechanism, epidemiology, management, and Prevention. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2018;24(10):2173–2182.

- Winthrop KL, Melmed GY, Vermeire S, et al. Herpes zoster infection in patients with ulcerative colitis receiving tofacitinib. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2018;24(10):2258–2265.

- Curtis JR, Xie F, Yun H, et al. Real-world comparative risks of herpes virus infections in tofacitinib and biologic-treated patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75(10):1843–1847.

- Valor-Mendez L, Voskens C, Rech J, et al. Herpes simplex infection in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis treated with baricitinib: a case report. Rheumatology (Oxford). Apr 6 2021;60(4):e122–e123.

- Tong LX, Jackson J, Kerstetter J, et al. Reactivation of herpes simplex virus infection in a patient undergoing ruxolitinib treatment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70(3):e59–e60.

- He H, Guttman-Yassky E. JAK inhibitors for atopic dermatitis: an Update. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2019;20(2):181–192.

- Rodrigues MA, Torres T. JAK/STAT inhibitors for the treatment of atopic dermatitis. J Dermatolog Treat. 2020;31(1):33–40.

- Wang V, Boguniewicz J, Boguniewicz M, et al. The infectious complications of atopic dermatitis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2021;126(1):3–12.

- Rystedt I, Strannegard IL, Strannegard O. Recurrent viral infections in patients with past or present atopic dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. 1986;114(5):575–582.

- Ong PY, Leung DY. The infectious aspects of atopic dermatitis. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2010;30(3):309–321.

- Wollenberg A, Zoch C, Wetzel S, et al. Predisposing factors and clinical features of eczema herpeticum: a retrospective analysis of 100 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49(2):198–205.

- Liaw FY, Huang CF, Hsueh JT, et al. Eczema herpeticum: a medical emergency. Can Fam Physician. 2012;58(12):1358–1361.

- Finlow C, Thomas J. Disseminated herpes simplex virus: a case of eczema herpeticum causing viral encephalitis. J R Coll Physicians Edinb. 2018;48(1):36–39.

- Beck LA, Boguniewicz M, Hata T, et al. Phenotype of atopic dermatitis subjects with a history of eczema herpeticum. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;124(2):260–269, 269 e1-7.

- Bieber T, Thyssen JP, Reich K, et al. Pooled safety analysis of baricitinib in adult patients with atopic dermatitis from 8 randomized clinical trials. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2021;35(2):476–485.

- King B, Maari C, Lain E, et al. Extended safety analysis of baricitinib 2 mg in adult patients with atopic dermatitis: an integrated analysis from eight randomized clinical trials. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2021;22(3):395–405.

- Winthrop KL, Harigai M, Genovese MC, et al. Infections in baricitinib clinical trials for patients with active rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2020;79(10):1290–1297.

- Harigai M, Takeuchi T, Smolen JS, et al. Safety profile of baricitinib in japanese patients with active rheumatoid arthritis with over 1.6 years median time in treatment: an integrated analysis of phases 2 and 3 trials. Mod Rheumatol. 2020;30(1):36–43.

- Silverberg JI, Simpson EL, Thyssen JP, et al. Efficacy and safety of abrocitinib in patients with moderate-to-Severe atopic dermatitis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156(8):863–873.

- Reich K, Teixeira HD, de Bruin-Weller M, et al. Safety and efficacy of upadacitinib in combination with topical corticosteroids in adolescents and adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (AD up): results from a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2021;397(10290):2169–2181.

- K Reich JL, Costanzo A. Safety of baricitinib in patients with atopic dermatitis: results of pooled data from two phase 3 monotherapy randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled 16-week trials (BREEZE-AD1 and BREEZE-AD2). presented at: American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) 2020 - 78th Annual Meeting; 2020.

- Michal Adamczyk BW. Atopic Dermatitis during Treatment with Selective JAK1 Inhibitor: a case report. Atopic Dermatitis and Pruritus: Interesting Cases. 2021.

- Leung DY. Why is eczema herpeticum unexpectedly rare? Antiviral Res. 2013;98(2):153–157.

- Insinga RP, Itzler RF, Pellissier JM, et al. The incidence of herpes zoster in a United States administrative database. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(8):748–753.

- Perry CM, Faulds D. Valaciclovir. A review of its antiviral activity, pharmacokinetic properties and therapeutic efficacy in herpesvirus infections. Drugs. 1996;52(5):754–772.

- Gnann JW, Jr., Barton NH, Whitley RJ. Acyclovir: mechanism of action, pharmacokinetics, safety and clinical applications. Pharmacotherapy. 1983;3(5):275–283.

- Xiao A, Tsuchiya A. Eczema herpeticum. StatPearls. 2021.

- Gold D, Corey L. Acyclovir prophylaxis for herpes simplex virus infection. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1987;31(3):361–367.

- Tyring SK, Baker D, Snowden W. Valacyclovir for herpes simplex virus infection: long-term safety and sustained efficacy after 20 years' experience with acyclovir. J Infect Dis. 2002;186(s1):S40–S46.

- Perazella MA. Crystal-induced acute renal failure. Am J Med. 1999;106(4):459–465.

- Saral R, Burns WH, Laskin OL, et al. Acyclovir prophylaxis of herpes-simplex-virus infections. N Engl J Med. 1981;305(2):63–67.

- Kawamura K, Hayakawa J, Akahoshi Y, et al. Low-dose acyclovir prophylaxis for the prevention of herpes simplex virus and varicella zoster virus diseases after autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Int J Hematol. 2015;102(2):230–237.

- Tyring SK, Douglas JM, Jr., Corey L, et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled comparison of oral valacyclovir and acyclovir in immunocompetent patients with recurrent genital herpes infections. The valaciclovir international study group. Arch Dermatol. 1998;134(2):185–191.

- Gupta R, Wald A, Krantz E, et al. Valacyclovir and acyclovir for suppression of shedding of herpes simplex virus in the genital tract. J Infect Dis. 2004;190(8):1374–1381.

- Warkentin DI, Epstein JB, Campbell LM, et al. Valacyclovir versus acyclovir for HSV prophylaxisin neutropenic patients. Ann Pharmacother. 2002;36(10):1525–1531.

- Fukushima T, Sato T, Nakamura T, et al. Daily 500 mg valacyclovir is effective for prevention of varicella zoster virus reactivation in patients with multiple myeloma treated with bortezomib. Anticancer Res. 2012;32(12):5437–5440.

- Gilbert S, McBurney E. Use of valacyclovir for herpes simplex virus-1 (HSV-1) prophylaxis after facial resurfacing: a randomized clinical trial of dosing regimens. Dermatol Surg. 2000;26(1):50–54.

- 500mg Valacyclovir Prescribed Online. GoodRx. 2021.

- Guttman-Yassky E, Thaci D, Pangan AL, et al. Upadacitinib in adults with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis: 16-week results from a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;145(3):877–884.