The development of biologic therapies, from TNF-inhibitors to IL-12/IL-23, IL-17, and IL-23 inhibitors, has revolutionized our ability to treat psoriasis. With so many great treatment options now available, deciding which biologic agent to choose can be daunting. Comorbidities may affect this decision, with the most common comorbidity being psoriatic arthritis (PsA). While many biologic therapies have been approved for PsA; some, such as risankizumab and brodalumab, are not. How much should the presence of PsA, and whether or not a biologic is FDA-approved for PsA, affect the treatment choice?

FDA approval guarantees that a drug is more effective, on average, than placebo. At the same time, lack of FDA-approval does not mean that a drug is necessarily ineffective. The FDA approval process is not what makes a drug effective. Following the publication of phase 3 clinical trial results, the Pfizer and Moderna COVID-19 vaccines were in use for at least 8 months prior to FDA approval, and they were highly effective before they received approval. Similarly, we have extensive data that brodalumab, risankizumab, and tildrakizumab – three FDA-approved psoriasis treatments that are not yet approved for PsA – are effective for PsA (). In phase 3 clinical trials, brodalumab [NCT02024646] and risankizumab [NCT03675308] were more effective than placebo at improving PsA symptoms. Tildrakizumab improved PsA symptoms in phase 2 trials. Brodalumab PsA trial results were published in February 2021 (Citation1), and FDA standard review, a 10-month process, for approval of risankizumab for PsA began in April 2021 (Citation2). While not yet FDA-approved for PsA, brodalumab, risankizumab, and tildrakizumab are certainly likely to improve PsA in many patients.

Table 1. FDA-approved drugs for psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis.

Do we need to choose a treatment that is FDA-approved to ‘prevent joint progression’ for psoriasis patients with psoriatic arthritis? Several FDA-approved PsA treatments are also approved for the inhibition of progression of structural damage, one of the main goals of therapy in patients with PsA, and some are not. Structural damage is measured by the modified Sharp van der Heijde score for PsA (SvdH), a radiographic scoring method that assigns scores for bony erosions and joint space narrowing in the hands, wrists, feet, and DIP joints (Citation3). Progression is indicated by a positive change in the SvdH score over time. While many FDA-approved psoriasis treatments are statistically significantly more effective than placebo in preventing SvdH change, or progression, most patients (>80%) in both treatment and placebo groups had a sub-threshold SvdH change (Citation4). In other words, no measurable progression was observed in the majority of patients in both groups. If most patients do not progress, then few patients will likely get more benefit from a drug that is FDA-approved to inhibit progression than from a drug that isn’t FDA-approved to inhibit joint progression. If most patients actually do progress, and the study periods are just not long enough to capture meaningful progression data, then the identified treatment effects of the trials upon which approval was based were likely small (Citation3). On the flipside, golimumab, ustekinumab, and tofacinitib, which are approved by the European Medicines Agency for the inhibition of structural progression, likely inhibit joint progression despite lack of FDA approval for doing so. Approval may not equate to meaningful benefit for many of our patients; lack of approval is similarly ambiguous.

The relative value of FDA approval should be factored into a discussion of tradeoffs. Tradeoffs occur when weighing the different factors in our decision of biologic choice. Since most patients might see little difference in PsA outcomes between psoriasis treatments that are or are not FDA-approved for PsA, small differences in safety or long term benefit for psoriasis control might weigh more heavily in the decision of which biologic to choose than FDA approval for PsA. For example, choosing an IL-17 inhibitor for a psoriasis patient because it is approved for PsA would need to be balanced against the small risk of inflammatory bowel disease. It may not necessarily be sensible to choose a treatment that is FDA-approved for PsA just because a psoriasis patient has joint pain.

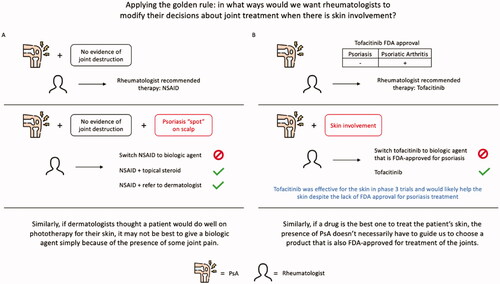

The ideal management strategy for psoriasis patients with PsA may involve a partnership between dermatologists and rheumatologists. One way to consider the impact PsA should have on dermatologists’ treatment decisions is by applying the ‘golden rule’ (). In what ways would we want rheumatologists to modify their decisions about joint treatment when there is skin involvement? Assume for a moment a rheumatologist evaluated a patient’s joints—finding no evidence of joint destruction – and thought an NSAID was appropriate treatment. If the patient asked, ‘I also have a spot of psoriasis on my scalp; will the NSAID clear that up, too?’ would we want the rheumatologist to switch from the NSAID to a biologic to get control of both the joints and the skin? Heavens no; we’d want the rheumatologist to either give the patient a topical steroid to use for the spot or, if the rheumatologist were at all unsure of appropriate treatment, refer the patient to a dermatologist. Similarly, if we thought a patient would do well on phototherapy for their skin, it may not be best to give a biologic simply because of the presence of some joint pain.

Figure 1. The ‘golden rule’ for dermatologists in the management of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. To understand how a dermatologist should modify treatment when there is joint pain, we can ask whether we would want rheumatologists to modify joint treatment when there is skin involvement. A) For example, a rheumatologist might recommend an NSAID for a patient’s psoriatic arthritis (PsA). Dermatologists would not want the rheumatologist to instead prescribe a biologic agent for the joints just because the patient had skin involvement. Topical steroids might have been the choice of treatment for the skin. Similarly, then, dermatologists probably should not be giving patients who don’t need a biologic for their skin a biologic just because there is some arthritis. An NSAID might have been the rheumatologist’s choice of treatment. B) In a second example, if the rheumatologist thought that tofacitinib, which is FDA-approved for PsA but not psoriasis, is the best therapy for the patient’s joints, we would not want the rheumatologist to instead switch to a biologic just because there is skin involvement. In phase 3 randomized trials, tofacitinib was more effective than placebo for improving psoriasis and would likely help this patient’s skin in addition to joints. Similarly, when a psoriasis patient has joint pain, we do not need to choose a PsA-approved agent over what would otherwise have been the best therapy for our patient’s skin.

If a rheumatologist thought tofacitinib – a drug approved for PsA and not for psoriasis, despite its effectiveness for psoriasis—would be the best treatment for the joints, would we want the rheumatologist to switch to a biologic if the patient also had skin involvement? We don’t think so; the tofacitinib would likely help the skin despite the lack of FDA-approval for psoriasis treatment. Similarly, if we think a drug is the best one to treat the patient’s skin, the presence of PsA doesn’t necessarily have to guide us to choose a product that is also FDA-approved for treatment of the joints.

As new psoriasis treatments become available, we should consider the available data and the limitations of FDA approval when choosing therapies for our psoriasis patients with PsA. For many patients, choosing what we think is best for the skin may be fine, as treatments that get rid of the inflammation in the skin are likely to also be effective for the joints, too, with or without FDA-approval.

Conflicts of interest

Feldman has received research, speaking and/or consulting support from Eli Lilly and Company, GlaxoSmithKline/Stiefel, AbbVie, Janssen, Alovtech, vTv Therapeutics, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Samsung, Pfizer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Amgen Inc, Dermavant, Arcutis, Novartis, Novan, UCB, Helsinn, Sun Pharma, Almirall, Galderma, Leo Pharma, Mylan, Celgene, Valeant, Menlo, Merck & Co, Qurient Forte, Arena, Biocon, Accordant, Argenx, Sanofi, Regeneron, the National Biological Corporation, Caremark, Advance Medical, Suncare Research, Informa, UpToDate and the National Psoriasis Foundation. He is also the founder and majority owner of www.DrScore.com [drscore.com] and founder and part owner of Causa Research. Mr Warren H. Chan and Mr. Rohan Singh have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- Mease P, Helliwell P, Hjuler K, et al. Brodalumab in psoriatic arthritis: results from the randomised phase III AMVISION-1 and AMVISION-2 trials. Ann Rheum Dis. 2021;80(2):185–193.

- AbbVie News Center. AbbVie submits regulatory applications for SKYRIZI® (risankizumab) in psoriatic arthritis to FDA and EMA. [cited 2021 Aug 26]. Available from: https://news.abbvie.com/news/press-releases/abbvie-submits-regulatory-applications-for-skyrizi-risankizumab-in-psoriatic-arthritis-to-fda-and-ema.htm

- van der Heijde D, Gladman DD, Kavanaugh A, et al. Assessing structural damage progression in psoriatic arthritis and its role as an outcome in research. Arthritis Res Ther. 2020;22(1):1–9.

- Gottlieb A, Merola J. Psoriatic arthritis for dermatologists. J Dermatolog Treat. 2020;31(7):662–679.