Abstract

Background

Abrocitinib, a once-daily, oral Janus kinase 1 selective inhibitor, was shown to be an effective treatment for moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis in phase 2 b/3 monotherapy trials.

Methods

These analyses included data for Investigator’s Global Assessment responder (clear [0] or almost clear [Citation1] with ≥2-grade improvement) and nonresponder patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis who received abrocitinib (200 mg or 100 mg) or placebo in three abrocitinib monotherapy trials (phase 2 b, NCT02780167; two phase 3, NCT03349060/JADE MONO-1 and NCT03575871/JADE MONO-2). Outcomes measuring skin clearance, itch, and quality of life were evaluated.

Results

Both nonresponders (n = 548) and responders (n = 260) treated with abrocitinib had rapid and clinically meaningful improvement in skin clearance, itch, and quality of life compared with placebo.

Conclusion

Patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis treated with abrocitinib who did not achieve an Investigator’s Global Assessment 0/1 response at week 12 still experienced rapid, clinically meaningful improvements across several other validated measures of efficacy and quality of life.

ClinicalTrials.gov

NCT02780167, NCT03349060, NCT03575871

Introduction

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a chronic inflammatory skin disease that affects up to 20% of children and adolescents and up to 10% of adults (Citation1–3). The most bothersome symptom of AD is itch, which is associated with significantly lower quality of life (QoL) and sleep disturbance (Citation2,Citation4–6). Current AD treatment guidelines recommend emollients, topical corticosteroids, topical calcineurin inhibitors, and phototherapy, depending on the severity of the disease (Citation7–9). Systemic immunosuppressive agents (e.g. corticosteroids, methotrexate, ciclosporin, azathioprine) are used both off- and on-label in various countries to treat moderate to severe or severe refractory AD (Citation7–9). These treatments are often insufficient to manage the signs and symptoms of moderate-to-severe AD or may be associated with considerable adverse events (AEs) (Citation7,Citation10–12). Dupilumab, a biologic targeting the interleukin (IL)–4Rα receptor and consequently inhibiting IL-4 and IL-13 signaling (Citation13,Citation14), is approved in a number of countries to treat patients with moderate-to-severe AD as young as 6 years of age (Citation15–21). However, not all dupilumab-treated patients achieve response based on the most commonly used efficacy measures of AD signs (i.e. Investigator’s Global Assessment [IGA] response [clear (0) or almost clear (1) with ≥2-grade improvement] (Citation14), ≥75% improvement in Eczema Area and Severity Index [EASI-75]) and symptoms (i.e. Peak Pruritus Numerical Rating Scale [PP-NRS]) (Citation22), and patients may find the treatment inconvenient because it requires subcutaneous injection (Citation14,Citation23,Citation24). Additionally, conjunctivitis has been reported in ≥10% of patients treated with dupilumab in real-world studies (Citation25).

Abrocitinib is a Janus kinase 1 (JAK1) selective inhibitor that is administered orally once daily. It modulates the signaling of key cytokines involved in AD pathogenesis and chronic itch, including IL-4, IL-13, IL-22, IL-31, and thymic stromal lymphopoietin. AD skin lesions are characterized by overexpression of T helper type (Th)–2 cytokines (IL-4, IL-13, and IL-31) and Th22 cytokines (IL-22) that require Janus kinase–signal transducer and activator of transcription (JAK-STAT) downstream signaling for their function; thymic stromal lymphopoietin uses JAK1 and JAK2 to activate STAT5 proteins (Citation26–28). Abrocitinib was effective and well-tolerated in phase 2 b and phase 3 monotherapy trials for moderate-to-severe AD (Citation29–31). The phase 2 b trial in adults with moderate-to-severe AD showed that abrocitinib monotherapy was safe and reduced signs and symptoms of AD (Citation29). In the JADE MONO-1 and JADE MONO-2 phase, 3 monotherapy trials in adolescents and adults with moderate-to-severe AD, statistically significantly greater proportions of abrocitinib-treated (200 mg or 100 mg) patients versus placebo-treated patients achieved an IGA 0/1 response, one of the coprimary endpoints of the studies (Citation30,Citation31).

Although IGA response is used as a primary endpoint in AD trials (Citation32), this endpoint does not provide a comprehensive assessment of disease improvement in many patients. By design, IGA globally measures erythema, edema/papulation, and oozing/crusting (Citation33) but does not directly measure improvements in the percentage of body surface area (%BSA) affected, symptoms of AD (e.g. sleep loss, itch), or overall QoL. IGA response is considered one of the most stringent clinical response criteria (Citation32). Hence, patients who do not achieve an IGA response may still have clinically meaningful improvements in AD signs and symptoms, and QoL. We investigated a broad array of validated efficacy and QoL measures in patients with moderate-to-severe AD who did not achieve IGA 0/1 responses at week 12 in abrocitinib monotherapy trials.

Methods

Study design

Data from a phase 2 b trial (NCT02780167) and two phase 3 trials (NCT03349060, JADE MONO-1; NCT03575871, JADE MONO-2) were included in this analysis; primary efficacy and safety results have been previously reported (Citation29–31). All study documents and procedures were approved by the appropriate institutional review board or ethics committee at each study site. Patients were randomly assigned 1:1:1:1:1 in the phase 2 b study to receive abrocitinib (200 mg, 100 mg, 30 mg, or 10 mg) or placebo and 2:2:1 in the phase 3 studies to receive abrocitinib (200 mg or 100 mg) or placebo. Data for IGA nonresponder and responder patients who received abrocitinib 200 mg, abrocitinib 100 mg, or placebo in the three abrocitinib monotherapy trials were pooled.

All three studies were conducted in compliance with the ethical principles originating in or derived from the Declaration of Helsinki and in compliance with all the International Council for Harmonization Guideline for Good Clinical Practice. All local regulatory requirements were followed. The studies were approved by an institutional review board or ethics committee at each study site and an internal review committee monitored the safety of patients throughout the studies. All patients provided written informed consent before inclusion.

Patients

Study participants were patients aged 18 to 75 years (phase 2 b) or ≥12 years (phase 3) with a clinical diagnosis of moderate-to-severe AD (IGA ≥3, EASI ≥12 [phase 2 b] or ≥16 [phase 3], %BSA ≥10, and PP-NRS ≥4 [phase 3 only; used with permission of Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc. and Sanofi]) (Citation22) for ≥1 year and a recent (within 12 months in phase 2 b; within 6 months in phase 3) history of inadequate response to topical medications (corticosteroids or calcineurin inhibitors) given for ≥4 weeks, or an inability to receive topical treatment because it was medically inadvisable, or who had required systemic therapies for control of their disease (phase 3 only) (Citation29–31). Previous dupilumab use was permitted in the phase 3 studies if it had been discontinued >6 weeks before study initiation (Citation30,Citation31).

Patients who previously used JAK inhibitors within 12 weeks (phase 2 b) or ever (phase 3) or oral immunosuppressive agents (e.g. ciclosporin, azathioprine, methotrexate, mycophenolate mofetil, systemic corticosteroids) within 4 weeks or 5 half-lives (whichever was longer) were excluded from the studies. Rescue medication was prohibited during the studies. Full inclusion and exclusion criteria are published elsewhere (Citation29–31).

Study endpoints and efficacy measures

The primary endpoint in the phase 2 b study was the proportion of patients achieving an IGA response at week 12; the coprimary endpoints in the phase 3 studies were the proportions of patients achieving an IGA response and the proportions of patients achieving EASI-75 at week 12 (Citation29–31). Several other efficacy measures were evaluated, including ≥50% improvement in EASI (EASI-50); Pruritus-NRS (phase 2 b; self-report of itch in the last 24 h)/PP-NRS (phase 3; self-report of worst itch in the last 24 h), hereafter referred to as PP-NRS for simplicity; %BSA affected; Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure (POEM); Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI); SCORing Atopic Dermatitis (SCORAD); and Patient Global Assessment (PtGA) (Citation29–31).

Statistical analyses

Binary endpoints were analyzed using the Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test, adjusted by randomization strata. Patients who permanently discontinued the study were defined as nonresponders at all visits after the last observation. Continuous endpoints were analyzed using a mixed-effects model with repeated measures based on all observed data. The model included factors for the treatment group, randomization strata, visit, treatment-by-visit interaction, and relevant baseline value. Times to achieve ≥3-point improvement from baseline in PP-NRS (PP-NRS3) and ≥4-point improvement from baseline in PP-NRS (PP-NRS4) responses were analyzed using Kaplan-Meier methods based on observed data only (no imputations), with times to event censored at treatment discontinuation, or last observation if no response was achieved. All safety data were summarized using descriptive statistics.

Results

Demographic and baseline characteristics

Demographic and baseline characteristics were comparable among pooled monotherapy nonresponders treated with abrocitinib or given placebo (). Among 548 IGA nonresponders, 368 (67.2%) were White, 120 (21.9%) were Asian, 44 (8.0%) were Black or African American, and 21 (3.8%) were Hispanic. More than half of the patients were male (333 [60.8%]). IGA nonresponder and responder populations generally had similar demographics and baseline disease characteristics. However, a greater proportion of IGA responders had a moderate disease at baseline compared with IGA nonresponders (IGA score of 3: 72.7% vs 58.8%; moderate disease based on PtGA: 46.9% vs 42.9%), and IGA responders were older on average (37.7 years vs 32.8 years; , ). The demographic and baseline characteristics were comparable among the three included studies (Citation34).

Table 1. Demographic and baseline characteristics of IGA nonresponders.

Improvement of AD signs in IGA nonresponders and responders

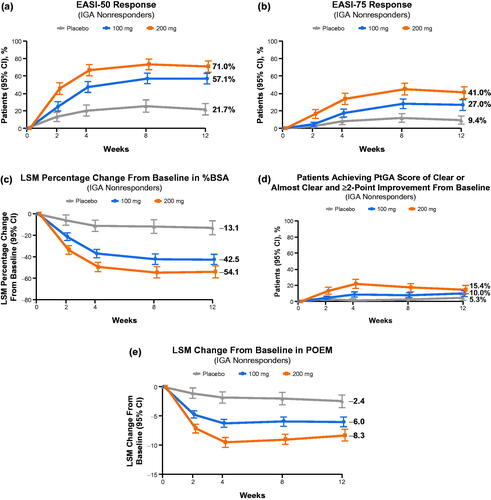

Among 548 (58.2% of total pooled monotherapy set) IGA nonresponders, the proportions of patients with EASI-50 responses at week 12 were 71.0% (95% CI: 645–77.6), 57.1% (50.6–63.5), and 21.7% (14.9–28.6) for the 200 mg, 100 mg, and placebo groups, respectively (). The proportions of patients with EASI-75 responses at week 12 were 41.0% (95% CI: 33.9–48.1) for 200 mg, 27.0% (21.2–32.8) for 100 mg, and 9.4% (4.5–14.3) for placebo (). Proportions of IGA nonresponders achieving EASI-50 and EASI-75 responses were higher with abrocitinib treatment at each time point compared with placebo, with differences observed early and persisting; the differences in response in the abrocitinib versus placebo arms were observed as early as week 2 and continued to be observed through week 12 for both doses of abrocitinib (). Among IGA responders at week 12, all achieved EASI-50, and 99.3% (95% CI: 98.0–100.0), 94.8% (90.4–99.2), and 75.0% (53.8–96.2) of IGA responders in the 200 mg, 100 mg, and placebo groups, respectively, also achieved EASI-75 ().

Figure 1. Improvement in signs and symptoms of atopic dermatitis in Investigator’s Global Assessment (IGA) nonresponders. (a) Proportions of patients who achieved EASI-50 response. (b) Proportions of patients who achieved EASI-75 response. (c) The least squares mean (LSM) percentage change from baseline in percentage of affected body surface area (%BSA). (d) Proportions of patients who achieved Patient Global Assessment (PtGA) score of clear or almost clear and ≥2-point improvement from baseline. (e) LSM change from baseline in Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure (POEM). aMinimal clinically important difference for POEM is 3.4 points (Citation35). EASI-50: ≥50% improvement on the Eczema Area and Severity Index; EASI-75: ≥75% improvement on the Eczema Area and Severity Index.

Among the IGA nonresponders, the least squares mean (LSM) change from baseline through week 12 in %BSA affected were −54.1 (95% CI: −59.9 to −48.3), −42.5 (−47.7 to −37.2), and −13.1 (−19.8 to −6.4) for the 200 mg, 100 mg, and placebo groups, respectively. The differences in response for both doses of abrocitinib versus placebo in %BSA affected were observed as early as week 2 for both doses of abrocitinib, and these benefits continued to be observed through week 12 (). Similar changes in %BSA affected were observed in IGA responders across treatment arms (–89.9 [95% CI: −92.2 to −87.7], −89.0 [–91.7 to −86.2], and −81.2 [–88.0 to −74.4]) at week 12 ().

A greater proportion of IGA nonresponders treated with abrocitinib assessed their skin as being “clear” or “almost clear” (0 or 1 on PtGA scale) at week 12 compared with IGA nonresponders treated with placebo: 15.4% (95% CI: 10.1–20.6), 10.0% (6.0–14.0), and 5.3% (1.5–9.1) for the 200 mg, 100 mg, and placebo groups, respectively. The differences in PtGA response for both doses of abrocitinib versus placebo were observed as early as week 2 (200 mg) or 4 (100 mg) and continued to be observed until week 12 (). Similar PtGA responses were observed in IGA responders across treatment arms (66.0% [95% CI: 58.2–73.7], 50.0% [40.0–60.0], and 33.3% [9.5–57.2]) at week 12 ().

For IGA nonresponders, the LSM changes in POEM from baseline to week 12 were meaningful for both doses of abrocitinib compared with placebo; −8.3 (95% CI: −9.3 to −7.3), −6.0 (−6.9 to −5.1), and −2.4 (−3.6 to −1.3) for the 200 mg, 100 mg, and placebo groups, respectively. The differences in response in the abrocitinib versus placebo arms in POEM were observed at week 2, and these benefits continued to be observed through week 12 for both doses of abrocitinib (). Similar LSM changes in POEM from baseline through week 12 were observed in IGA responders across treatment arms (–15.7 [95% CI: −16.4 to −14.9], −14.6 [–15.5 to −13.6], and −10.8 [–13.2 to −8.5]) at week 12 ().

Improvement of AD symptoms in IGA nonresponders and responders

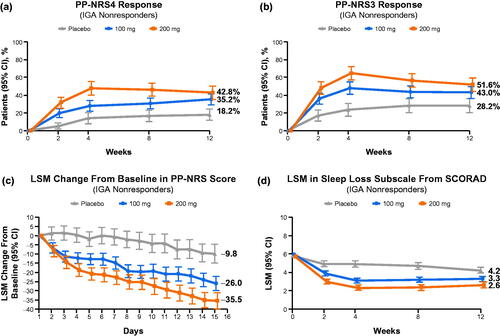

Greater proportions of IGA nonresponders treated with abrocitinib 200 mg and 100 mg achieved itch relief, as indicated by ≥4-point improvement in PP-NRS score (PP-NRS4) compared with those treated with placebo: 42.8% (95% CI: 35.1–50.4), 35.2% (28.6–41.9), and 18.2% (11.3–25.1) in the 200-mg, 100-mg, and placebo groups, respectively (). Furthermore, clinically meaningful ≥3-point improvements in PP-NRS score (PP-NRS3) were achieved by 51.6% (95% CI: 43.8–59.4), 43.0% (35.9–50.1), and 28.2% (20.1–36.4) of IGA nonresponders in the 200-mg, 100-mg, and placebo groups, respectively (). Differences in PP-NRS4 or PP-NRS3 responses between abrocitinib and placebo arms were observed when assessed at week 2 and observed at all time points thereafter (). LSM reductions in PP-NRS in abrocitinib-treated patients were greater for both abrocitinib doses versus placebo as early as day 2 (24 h after administration of the first dose) and were maintained through day 15 (). Similar results across treatment arms (PP-NRS4: 83.0% [95% CI: 76.4–89.6], 78.0% [69.1–87.0], and 57.1% [6.7–59.2]; PP-NRS3: 93.6% [89.3–97.9], 89.2% [82.5–95.8], and 64.3% [39.2–89.4]; and LSM reductions: −54.0 [–59.7 to −48.3], −41.8 [–48.8 to −34.7], and −12.8 [–30.1 to 4.5]) were observed for IGA responders at week 12 ().

Figure 2. Improvement in itch in Investigator’s Global Assessment (IGA) nonresponders. (a) Proportions of patients with PP-NRS4 response.a (b) Proportions of patients with PP-NRS3 response.a (c) Least squares mean (LSM) change from baseline in PP-NRS score. (d) LSM on the sleep loss subscale of the SCORing Atopic Dermatitis (SCORAD) scale. aMinimal clinically important difference for PP-NRS score is 2.2–4.2 points (Citation22). PP-NRS: Peak Pruritus Numerical Rating Scale; PP-NRS3: ≥3-point improvement from baseline in PP-NRS score; PP-NRS4: ≥4-point improvement from baseline in PP-NRS score.

IGA nonresponders treated with abrocitinib showed lower levels of sleep disruption measured by the sleep loss subscale of the SCORAD at week 12 compared with patients treated with placebo, as shown by final LSM subscale scores at week 12 of 2.6 (95% CI: 2.3–3.0), 3.3 (3.0–3.6), and 4.2 (3.9–4.6) for the 200 mg, 100 mg, and placebo groups, respectively. The differences in response in the abrocitinib versus placebo arms were observed as early as week 2 for both doses of abrocitinib, and these benefits continued to be observed through week 12 (). A similar trend was observed in IGA responder patients across treatment arms (0.4 [95% CI: 0.2–0.7], 0.9 [0.5–1.2], and 1.3 [0.5–2.2]) at week 12 ().

Improvement of QoL in IGA nonresponders and responders

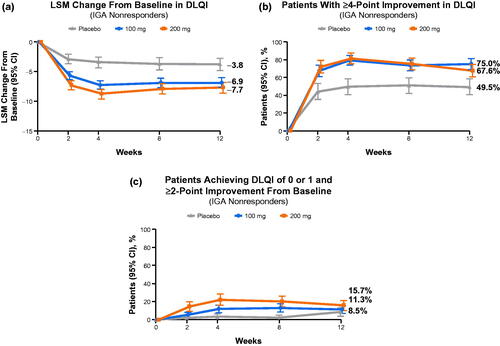

IGA nonresponders treated with abrocitinib reported meaningful QoL improvements at week 12 compared with placebo, as indicated by LSM reductions from baseline in DLQI of −7.7 (95% CI: −8.7 to −6.8), −6.9 (−7.7 to −6.0), and −3.8 (−4.9 to −2.7) for the 200 mg, 100 mg, and placebo groups, respectively (). At week 12, proportions of IGA nonresponders reporting ≥4-point improvement in DLQI were 67.6% (95% CI: 60.0–75.1), 75.0% (68.7–81.3), and 49.5% (40.2–58.9) for the 200 mg, 100 mg, and placebo groups, respectively (). Proportions of IGA nonresponders achieving DLQI of 0 or 1 (no effect on QoL) at week 12 were 15.7% (95% CI: 9.9 − 21.4), 11.3% (6.7 − 15.8), and 8.5% (3.4 − 13.5) for the 200 mg, 100 mg, and placebo groups, respectively (). In all QoL responses, the differences in the abrocitinib versus placebo arms were observed as early as week 2 and continued to be observed through week 12. A similar pattern in QoL responses was observed for IGA responders across treatment arms (LSM reductions: −12.0 [95% CI: −12.5 to −11.4], −11.1 [–11.8 to −10.4], and −9.4 [–11.1 to −7.7]; ≥4-point improvement in DLQI: 96.9% [93.8–99.9], 88.8% [81.8–95.7], and 80.0% [55.2–100.0]; DLQI 0/1: 54.3% [45.7–62.9], 51.8% [41.1–62.6], and 50.0% [23.28–76.2]) at week 12 ().

Figure 3. Improvement in quality of life in Investigator’s Global Assessment (IGA) nonresponders. (a) The least squares mean (LSM) change from baseline in Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI).a (b) Proportions of patients with ≥4-point improvement in DLQI. (c) Proportions of patients achieving DLQI of 0 or 1 and ≥ 2-point improvement from baseline. aMinimal clinically important difference for DLQI is 4 points (Citation36).

Safety of abrocitinib among IGA nonresponders and responders

Among IGA nonresponders, 71.2%, 68.1%, and 57.2% reported adverse events (AEs) in the 200 mg, 100 mg, and placebo groups, respectively. Serious AEs were reported in 3.8%, 2.7%, and 2.2% of nonresponders; 4.9%, 2.2%, and 4.3% of nonresponders discontinued treatment due to AEs. The pattern of safety events in IGA responders was similar: 75.5%, 63.9%, and 37.5% of IGA responders reported AEs in the 200 mg, 100 mg, and placebo groups, respectively. Serious AEs were reported in 1.4%, 1.0%, and 0% of responders in the 200-mg, 100-mg, and placebo groups, respectively; 0.7%, 2.1%, and 6.3% of responders discontinued treatment due to AEs.

Discussion

The results of this post hoc analysis show that IGA nonresponders achieved meaningful improvement in validated metrics of signs and symptoms of AD and health-related QoL after initiating treatment with abrocitinib (200 mg and 100 mg) compared with placebo. Although IGA is a common metric used for measuring AD lesion improvement (Citation32), IGA responder analyses do not provide a comprehensive assessment of disease improvement. The IGA does not directly measure improvements in %BSA affected, sleep loss, itch, or overall QoL. In addition, the criterion for response (0 [clear] or 1 [almost clear] with ≥2-grade improvement) is considered a high threshold (Citation37), especially when patients enrolled in clinical trials have often failed multiple systemic therapies. Overall, IGA nonresponders in this pooled analysis had more severe disease and were younger at baseline compared with IGA responders. The limitations of IGA are evident from the current analyses, which suggest that IGA nonresponders receiving abrocitinib achieve meaningful reductions in other clinical measures of AD disease severity and improvement in QoL versus placebo.

Regarding skin clearance, IGA nonresponders treated with abrocitinib still showed rapid improvement in terms of achieving EASI-50 or EASI-75 responses, which are considered clinically relevant (Citation40), compared with patients treated with placebo. Regarding AD symptoms, IGA nonresponders treated with abrocitinib showed rapid and clinically meaningful improvement in both itch and sleep loss compared with placebo. These improvements in signs and symptoms of AD translated to improvements in QoL; IGA nonresponders treated with abrocitinib achieved meaningful improvement in QoL (defined as a ≥ 4-point improvement in DLQI), and higher proportions of abrocitinib-treated IGA nonresponders achieved the stringent endpoint of DLQI 0/1 (no effect on QoL) compared with patients treated with placebo. Responses to abrocitinib followed a similar pattern in IGA nonresponders and responders, although the IGA responder population included more patients with moderate AD than the nonresponder population. In addition, this analysis showed that improvements in many signs and symptoms of AD were similar among IGA responder groups, regardless of the treatment received (i.e. abrocitinib or placebo). The findings of this analysis are also consistent with a recent dupilumab study in adolescent patients in which dupilumab improved other signs and symptoms of AD and QoL for IGA nonresponders compared with placebo (Citation38,Citation39). Although there are no direct comparisons between the efficacy of abrocitinib and dupilumab based on this pooled analysis, it does further detail the efficacy of IGA nonresponders and suggest that abrocitinib may provide greater improvements in signs and symptoms of AD in IGA nonresponders compared with dupilumab.

These analyses were limited by their post hoc nature. In addition, the Children’s Dermatology Life Quality Index was not included in this analysis; therefore, QoL improvement in adolescents (aged <18 years) was not measured. However, our results demonstrated clinically relevant QoL improvement in a large proportion (84.3%) of the IGA nonresponder population. Finally, all three primary studies included in this post hoc analysis were relatively short (12 weeks). Longer-duration studies providing further data regarding the long-term efficacy of abrocitinib will be published at a later date; a recent publication based on pooled JADE program data has demonstrated longer-term safety of abrocitinib (Citation40), supporting that with a proper patient and dose selection, abrocitinib has a manageable tolerability and safety profile for long-term use. In conclusion, the results reported here show that patients who initially do not achieve IGA response with abrocitinib can still experience clinically meaningful improvements in the signs and symptoms of AD, with improvements in QoL.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (1.2 MB)Acknowledgments

Editorial/medical writing support under the guidance of the authors was provided by Irene Park, PhD, at ApotheCom, San Francisco, CA, USA, and was funded by Pfizer Inc., New York, NY, USA, in accordance with Good Publication Practice (GPP3) guidelines (Ann Intern Med 2015; 163: 461–464).

Disclosure statement

A.B. has served as a scientific adviser and/or clinical study investigator for Pfizer, AbbVie, Aligos, Almirall, Amgen, Arcutis, Arena Pharmaceuticals, Athenex, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, Dermavant, Eli Lilly, Evommune, Forté Pharma, Galderma, Incyte, Janssen, LEO Pharma, Novartis, Rapt Therapeutics, Regeneron, Sanofi Genzyme, Sun Pharmaceuticals, and UCB Pharma. M.B. has been a clinical study investigator for Regeneron and Incyte and served as a scientific adviser or consultant for Pfizer, AbbVie, Eli Lilly, LEO Pharma, Janssen, Regeneron, and Sanofi Genzyme. P.M.B. has received personal fees from Almirall, Sanofi, Janssen, Amgen, LEO Pharma, AbbVie, Pfizer, Boehringer Ingelheim, GSK, Regeneron, Eli Lilly, Celgene, Arena Pharma, Novartis, UCB Pharma, and Biotest, and is an investigator for Pfizer (grant paid to his institution). P.C.L. has served as a scientific adviser and/or clinical study investigator for Pfizer, AbbVie, Eli Lilly, Novartis, and Sanofi Genzyme, and as a paid speaker for Pfizer, AbbVie, Eli Lilly, Novartis, Sanofi Genzyme, Janssen, Pierre Fabre, and La Roche-Posay. P.B., M.D., and S.A.F. are employees and shareholders of Pfizer. R.R. and M.C.C. are former employees and shareholders of Pfizer. M.C.C. has served as a scientific adviser for Incyte and Abbvie.

Data availability statement

Upon request, and subject to review, Pfizer Inc. will provide the data that support the findings of this study. Subject to certain criteria, conditions and exceptions, Pfizer Inc. may also provide access to the related individual de-identified participant data. See https://www.pfizer.com/science/clinical-trials/trial-data-and-results for more information.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Chiesa Fuxench ZC, Block JK, Boguniewicz M, et al. Atopic dermatitis in America Study: a cross-sectional study examining the prevalence and disease burden of atopic dermatitis in the US adult population. J Invest Dermatol. 2019;139(3):583–590.

- Silverberg JI, Hanifin JM. Adult eczema prevalence and associations with asthma and other health and demographic factors: a US population-based study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;132(5):1132–1138.

- Williams H, Robertson C, Stewart A, et al. Worldwide variations in the prevalence of symptoms of atopic eczema in the international study of asthma and allergies in childhood. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1999;103(1):125–138.

- Augustin M, Langenbruch A, Blome C, et al. Characterizing treatment-related patient needs in atopic eczema: insights for personalized goal orientation. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34(1):142–152.

- Matterne U, Apfelbacher CJ, Loerbroks A, et al. Prevalence, correlates and characteristics of chronic pruritus: a population-based cross-sectional study. Acta Derm Venereol. 2011;91(6):674–679.

- Yosipovitch G, Bernhard JD. Clinical practice. Chronic pruritus. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(17):1625–1634.

- Boguniewicz M, Fonacier L, Guttman-Yassky E, et al. Atopic dermatitis yardstick: practical recommendations for an evolving therapeutic landscape. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2018;120(1):10–22.e2.

- Eichenfield LF, Ahluwalia J, Waldman A, et al. Current guidelines for the evaluation and management of atopic dermatitis: a comparison of the joint task force practice parameter and American Academy of Dermatology Guidelines. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;139(4S):S49–S57.

- Wollenberg A, Barbarot S, Bieber T, et al. Consensus-based European Guidelines for treatment of atopic eczema (atopic dermatitis) in adults and children: part II. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32(6):850–878.

- Eichenfield LF, Tom WL, Berger TG, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: section 2. Management and treatment of atopic dermatitis with topical therapies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71(1):116–132.

- Sidbury R, Davis DM, Cohen DE, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: section 3. Management and treatment with phototherapy and systemic agents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71(2):327–349.

- Sidbury R, Tom WL, Bergman JN, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: section 4. Prevention of disease flares and use of adjunctive therapies and approaches. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71(6):1218–1233.

- Blauvelt A, de Bruin-Weller M, Gooderham M, et al. Long-term management of moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis with dupilumab and concomitant topical corticosteroids (LIBERTY AD CHRONOS): a 1-year, randomised, double-blinded, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2017;389(10086):2287–2303.

- Simpson EL, Bieber T, Guttman-Yassky E, et al. Two phase 3 trials of dupilumab versus placebo in atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(24):2335–2348.

- Dupixent (dupilumab) injection, for subcutaneous use [package insert]. Tarrytown, NY (USA): Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc; 2020.

- Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc. Dupixent [summary of product characteristics]. Amsterdam (The Netherlands); European Medicines Agency; 2020.

- Sanofi-Aventis Canada Inc. Duxipent [product monograph]. Ottawa (Canad; Health Canada; 2019 Sep 25 [cited 2021 Jan 28]. Available from: https://pdf.hres.ca/dpd_pm/00053270.PDF.

- Sanofi-Aventis Australia Pty Ltd. Duxipent [public assessment report]. Woden ACT (Australia); Therapeutic Goods Administration; 2018 Jun 12 [cited 2021 Jan 28]. Available from: https://www.tga.gov.au/sites/default/files/auspar-dupilumab-180612.pdf.

- Katoh N, Kataoka Y, Saeki H, et al. Efficacy and safety of dupilumab in Japanese Adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: a subanalysis of three clinical trials. Br J Dermatol. 2020;183(1):39–51.

- Sanofi. Duxipent® (dupilumab) approved in China for adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis [press release]. Paris (France) and Tarrytown (NY); Sanofi; 2021 Jun 19. [cited 2021 Jan 28]. Available from: https://www.sanofi.com/en/media-room/press-releases/2020/2020-06-19-13-30-00.

- Giavina-Bianchi MH, Giavina-Bianchi P, Rizzo LV. Dupilumab in the treatment on severe atopic dermatitis refractory to systemic immunosuppression: case report. Einstein. 2019;17:eRC4599.

- Yosipovitch G, Reaney M, Mastey V, et al. Peak pruritus numerical rating scale: psychometric validation and responder definition for assessing itch in moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. 2019;181(4):761–769.

- Alten R, Kruger K, Rellecke J, et al. Examining patient preferences in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis using a discrete-choice approach. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2016;10:2217–2228.

- Boeri M, Sutphin J, Hauber B, et al. Quantifying patient preferences for systemic atopic dermatitis treatments using a discrete-choice experiment. J Dermatolog Treat. 2020;1–10. DOI:10.1080/09546634.2020.1832185

- Ferreira S, Torres T. Conjunctivitis in patients with atopic dermatitis treated with dupilumab. Drugs Context. 2020;9:2020-2-3. DOI:10.7573/dic.2020-2-3

- Oetjen LK, Mack MR, Feng J, et al. Sensory neurons co-opt classical immune signaling pathways to mediate chronic itch. Cell. 2017;171(1):217–228.e13.

- Howell MD, Kuo FI, Smith PA. Targeting the Janus Kinase family in autoimmune skin diseases. Front Immunol. 2019;10:2342.

- Klonowska J, Gleń J, Nowicki R, et al. New cytokines in the pathogenesis of atopic dermatitis-new therapeutic targets. IJMS. 2018;19(10):3086.

- Gooderham MJ, Forman SB, Bissonnette R, et al. Efficacy and safety of oral Janus kinase 1 inhibitor abrocitinib for patients with atopic dermatitis: a phase 2 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155(12):1371–1379.

- Simpson EL, Sinclair R, Forman S, et al. Efficacy and safety of abrocitinib in adults and adolescents with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (JADE Mono-1): a multicentre, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2020;396(10246):255–266.

- Silverberg JI, Simpson EL, Thyssen JP, et al. Efficacy and safety of abrocitinib in patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156(8):863–873.

- Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technology in Health (CADTH). Appendix 5: validity of outcome measures. In: Clinical review report: CRISABOROLE ointment, 2% (EUCRISA) (Pfizer Canada Inc.). Ottawa (Canada); CADTH; 2019 Apr [cited 2021 Jan 28]. Available from: https://www.cadth.ca/sites/default/files/cdr/clinical/sr0570-eucrisa-clinical-report.pdf.

- Rehal B, Armstrong AW, Armstrong A. Health outcome measures in atopic dermatitis: a systematic review of trends in disease severity and quality-of-life instruments 1985-2010. PLOS One. 2011;6(4):e17520.

- Silverberg JI, Thyssen JP, Simpson EL, et al. Impact of oral abrocitinib monotherapy on patient-reported symptoms and quality of life in adolescents and adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: a pooled analysis of patient-reported outcomes. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2021;22(4):541–554.

- Schram ME, Spuls PI, Leeflang MMG, et al. EASI (objective), SCORAD and POEM for atopic eczema: responsiveness and minimal clinically important difference. Allergy. 2012;67(1):99–106.

- Basra MKA, Salek MS, Camilleri L, et al. Determining the minimal clinically important difference and responsiveness of the dermatology life quality index (DLQI): further data. Dermatology. 2015;30:27–33.

- Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technology in Health (CADTH). Appendix 5: validity of outcome measures. In: Clinical review report: DUPILUMAB (DUPIXENT) (Sanofi Genzyme, a division of sanofi-aventis Canada Inc.). Ottawa (Canada); CADTH; 2020 Jun [cited 2021 Jan 28]. Available from: https://cadth.ca/sites/default/files/cdr/clinical/sr0636-dupixent-clinical-review-report.pdf.

- Paller AS, Bansal A, Simpson EL, et al. Clinically meaningful responses to dupilumab in adolescents with uncontrolled moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: post-hoc analyses from a randomized clinical trial. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2020;21(1):119–131.

- Silverberg JI, Simpson EL, Ardeleanu M, et al. Dupilumab provides important clinical benefits to patients with atopic dermatitis who do not achieve clear or almost clear skin according to the investigator’s global assessment: a pooled analysis of data from two phase III trials. Br J Dermatol. 2019;181(1):80–87.

- Simpson EL, Silverberg JI, Nosbaum A, et al. Integrated safety analysis of abrocitinib for the treatment of moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis from the phase ii and phase iii clinical trial program. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2021;22(5):693–707.