Abstract

Background

Psoriasis is often treated with biologic therapies. While many patients see improvement in their symptoms with treatment, some achieve only partial success.

Objective and Methods

In this post-hoc analysis we assess Psoriasis Area Severity Index (PASI) and Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) results from patients who switched to RZB due to suboptimal results that originally received ADA (N = 53, IMMvent NCT02694523) or UST (N = 172, UltIMMa-1 [NCT02684370], UltIMMa-2 [NCT02684357]).

Results

For patients originally treated with ADA, after three doses of RZB, 83.3% of PASI 50 to <75 patients improved to PASI ≥75 and for PASI 75 to <90 patients, 77.1% improved to PASI ≥90. For patients originally treated with UST, after 7 doses of RZB, 86.8% of PASI <75 patients improved to PASI ≥75 and 75.5% of PASI 75 to ≤90 patients improved to PASI ≥90. No patients demonstrated worsening from their initial PASI group after switching. There were no significant safety events associated with switching patients to RZB without a washout period.

Conclusion

For patients with an inadequate or incomplete response to UST or ADA, switching to RZB improved PASI scores and DLQI for patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis with no significant safety risks.

Introduction

Psoriasis is an inflammatory disease that causes red, itchy, scaly patches on the skin (Citation1). These lesions can reduce the quality of life in patients due to physical discomforts such as pain, stinging, or itching at the lesion site. Patients may also have a reduced quality of life from feelings of self-consciousness, embarrassment, or interfering with everyday life activities. For psoriasis patients, achieving and maintaining clear skin is a high priority, but quality of life is also an essential measure of patients’ satisfaction with their current treatment (Citation2).

Patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis have a variety of treatment options, including steroidal and non-steroidal topical agents, phototherapy, systemic non-biologics, and systemic biologics (Citation3). Common biologics for the treatment of moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis include tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) inhibitors, an interleukin (IL-) 12 and interleukin 23 (IL-12/23) inhibitor, IL-17 inhibitors, and IL-23 specific inhibitors.

Many patients treated with biologics achieve clear skin and reduced psoriasis symptoms, but some patients achieve only partial improvement of their symptoms. Patients may struggle reaching their treatment goals, which may differ, and in fact, be higher than those of the physician (Citation4,Citation5). Some patients also struggle with barriers to treatment due to difficulty obtaining a referral, lack of follow-up after initial treatment, and therapeutic failure (Citation4). Additionally, a patient’s initial response to a drug may decrease over time. Patients may also encounter clinical inertia, defined as the failure to initiate or intensify care when treatment goals are not met (Citation4). To meet patient needs and goals, switching biologic treatments is a viable option for patients with an inadequate response to their current treatment.

Risankizumab (RZB) is an IL-23 inhibitor that binds to the p19 subunit to specifically inhibit IL-23. RZB has demonstrated superiority over the IL-12/23 inhibitor, ustekinumab (UST), through 52 weeks of treatment (Citation6), in the treatment of moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis. RZB has also demonstrated superiority over adalimumab (ADA), a TNF-α inhibitor, for the treatment of moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis (Citation7).

Here, we report the improvements in PASI and DLQI results of switching to RZB in patients with a suboptimal response to UST or ADA to provide clinicians much needed data on the improvement and speed of patient responses after switching.

Materials and methods

ADA switch population

Patients (N = 53) who achieved 50% improvement in Psoriasis Area Severity Index (PASI 50) to less than PASI 90 were rerandomized to switch from ADA to RZB at week 16 in the phase 3 trial, IMMvent (NCT02694523). This trial enrolled patients who had moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis for at least six months as defined by a body surface area affected ≥10%, a PASI score of ≥12, or a static Physicians Global Assessment score of greater than or equal to three. Patients also needed to be a candidate for systemic therapy with ADA. Key exclusion criteria were patients with non-plaque forms of psoriasis, drug-induced psoriasis or an active inflammatory disease other than psoriasis, prior exposure to RZB or ADA, known acute or chronic infections, and active, suspected, or a history of malignancy within the past five years except appropriately treated skin and uterine carcinomas. Further details regarding the initial population have been reported in Reich et al. (Citation7).

UST switch population

Patients who switched from UST to RZB (N = 172) were initially randomized to UST in the UltIMMa-1 (NCT02684370) and UltIMMa-2 (NCT02684357) studies and switched to RZB upon entry to the open-label extension trial LIMMitless. Patients had a history of chronic moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis and were candidates to continue into the prolonged open-label RZB treatment (LIMMitless NCT03047395). Key exclusion criteria included premature discontinuation of UltIMMa-1 or -2, development of erythrodermic, pustular, or drug-induced psoriasis, development of HIV, hepatitis B, hepatitis C, or active tuberculosis infections, and active or suspected malignancies excluding treated basal cell carcinoma of the skin or in situ carcinoma of the uterine cervix. Further details regarding the initial population have been reported available in Gordon et al. (Citation6).

Study design

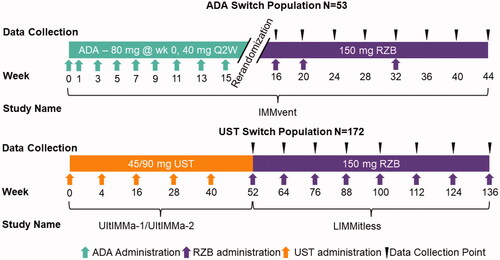

Patients in the ADA switch population received the approved dose of ADA for psoriasis; 80 mg of ADA at week 0, and 40 mg at week 1 (). They continued to receive 40 mg of ADA every other week thereafter (). At week 16, patients receiving ADA with PASI 50 to <90 were rerandomized to either continue ADA or switch to RZB without a washout period (). Patients that were rerandomized to receive RZB received 150 mg at weeks 16, 20, and 32 ().

Patients in the UST switch population received the approved dose for psoriasis in the USA, either 45 mg (<100 kg) or 90 mg (>100 kg) of UST at weeks 0, 4, and every 12 weeks thereafter through week 52 during the UltIMMa-1 and -2 studies (). Without a defined washout period, patients entered the LIMMitless trial and received open label 150 mg RZB every 12 weeks without a RZB loading dose ().

The studies were conducted in accordance with the protocol, International Council for Harmonization of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use guidelines, applicable local regulations and Good Clinical Practice guidelines governing clinical study conduct, and ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. All study-related documents (including study protocols) were approved by an institutional review board or independent ethics committee at each study site; all patients provided written informed consent prior to study participation. Further details can be found in the original reports for these studies (Citation6,Citation7).

Assessments and statistics

PASI scores and patient-reported outcomes from the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) were used to assess efficacy. For the ADA switch population, an inadequate response was defined as PASI ≥50 to <75 and an incomplete response was defined as PASI ≥75 to <90. In the UST switch population, an inadequate response was defined as PASI <75 and an incomplete response was defined as PASI ≥75 to <90. The Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) is a patient-driven quality-of-life survey for patients with dermatological diseases. A DLQI reduction of 5 points is considered the minimal clinically important difference. A DLQI score of 0 or 1 is considered the disease having no effect on the patient’s life (Citation8).

Data were described using summary statistics and were analyzed using SAS software version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC, USA). Statistical results were imputed using last observation carried forward (LOCF), observed cases (OC), non-responder imputation (NRI), or modified non-responder imputation (mNRI) where a non-response is imputed for treatment failures, defined as patients who have a worsening of psoriasis symptoms. Safety was assessed in all patients who received at least one dose of RZB.

Results

Baseline demographics

Baseline characteristics for ADA and UST switch populations are presented in . In the ADA switch population, the mean age was 49.5 years and 48.0 years in the UST switch population. The mean baseline PASI was 20.4 in the ADA switch population and 18.94 in the UST switch population. The mean baseline percent of body surface area (BSA) affected was 27.6% and 22.6% in the ADA and UST switch populations, respectively. Seventeen percent of ADA switch patients and 21.5% of UST switch patients had prior treatment with TNF-α inhibitors.

Table 1. Baseline demographics of the ADA and UST switch populations.

Patients switching from ADA to RZB

For patients switching from ADA with an inadequate response (PASI ≥50 to <75), the mean absolute PASI score was 7.1 before the switch and 5.0 after one RZB administration (Supplemental Table S1). For patients with an incomplete response (PASI ≥75 to <90), the mean absolute PASI score was 3.1 before the switch and 1.8 after one administration of RZB (Supplemental Table S1). At week 44, the mean improvement from baseline for patients switching to RZB was 92.9% (ANCOVA, p < .001) (Citation9). PASI 90 and 100 achievement rates also increased after switching to RZB (Citation7).

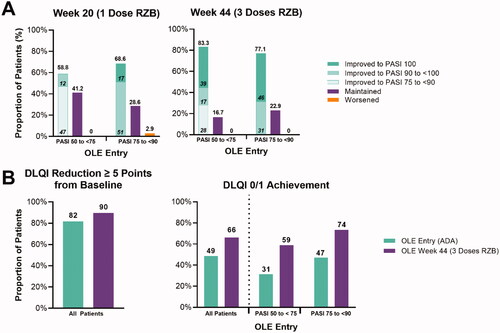

Rates of achieving PASI response thresholds also increased for patients switching from ADA to RZB. For patients with an inadequate response (PASI 50 to <70) to ADA, 58.8% of patient’s improved their PASI scores after one dose of RZB, and 83.3% had improved PASI scores after three doses (). After three doses, 38.9% of inadequate responders improved to PASI 100, 16.74% achieved PASI 90 to <100 and 16.7% maintained their response (). No patient’s PASI score dropped below their response category (inadequate or incomplete) at the time of switch (). For patients with an incomplete response (PASI 75 to <90) to ADA, 68.6% of patients improved after the first dose, and 77.1% improved after three doses of RZB (). After three doses, 45.7% of patients improved to PASI 100, 31.4% improved to PASI 90 to <100, 22.9% maintained their response, and no patient’s PASI score dropped below their response category (inadequate or incomplete) at the time of switch ().

Figure 2. Changes to PASI and DLQI for ADA switch patients. (A) Proportion of patients with improved, maintained, or worsened PASI scores after switching to RZB from ADA reported by LOCF. (B) Proportion of patients with reduced DLQI by five or more points and achieving DLQI of 0/1 reported by NRI for all patients and LOCF for stratified patients. RZB: risankizumab; ADA: adalimumab; LOCF: last observation carried forward; OLE: open label extension; PASI: Psoriasis Area and Severity Index; DLQI: Dermatology Life Quality Index; NRI: non-responder imputation.

A DLQI reduction of ≥5 points from baseline was achieved by 81.6% (LOCF 87%) of patients receiving ADA before switching. This number increased to 89.8% (LOCF 93.6%) after three doses of RZB (). At the switch from ADA to RZB, 31.3% (LOCF 51.4%) of inadequate responders had a DLQI of 0/1. After three doses of RZB, 58.8% (LOCF 68.6%) of patients achieved a DLQI of 0/1. Similarly, for incomplete responders to ADA, 73.5% of patients achieved a DLQI of 0/1 after switching and receiving three doses of RZB, compared to 47.1% prior to switching.

Patients switching from UST to RZB

For patients with an inadequate response (PASI <75) to UST, the mean absolute PASI at the time of RZB switch was 8.97, and after one treatment, the mean PASI score decreased to 2.96 (Supplemental Table S1). Patients with an incomplete (PASI ≥75 to <90) response to UST had a mean absolute PASI score of 3.31 at the time of RZB switch and 1.42 after their first dose (Supplemental Table S1). The mean percentage improvement in PASI score increased to 93.2% within 12 weeks of switching from UST to RZB (Citation10). After the first treatment of RZB (Week 64), 72.7% of patients achieved PASI 90, and 51.2% achieved PASI 100 (OC, Supplemental Table S2). PASI 90 achievement levels continued to increase after the second treatment and 83.1% of patients achieved PASI 90 after seven treatments (OC, Supplemental Table S2). PASI 100 rates showed a similar trend, with 52.7% achieving PASI 100 after two doses and 56.6% achieving PASI 100 after seven doses. These results are similar to those seen in patients switching from ADA to RZB in the IMMvent study (Citation7).

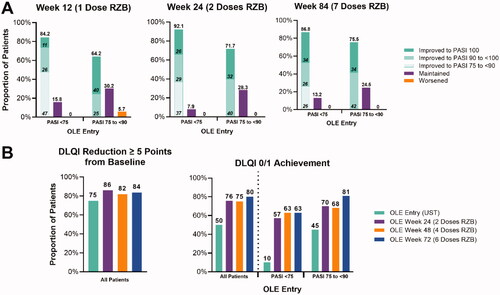

After switching from UST to RZB, a single dose of RZB resulted in 84.2% of patients with an inadequate response to UST improving their PASI scores (). Of these patients, 11% achieved PASI 100, 26% achieved PASI 90 to <100, and 47% improved to the PASI 75 to <90 range (). These results were maintained after two and seven doses (). After seven doses, no patient’s PASI score dropped below their response category (inadequate or incomplete) at the time of switch ().

Figure 3. Changes to PASI and DLQI for UST switch patients. (A) Proportion of patients with improved, maintained, or worsened PASI scores after switching to RZB from UST reported by LOCF. (B) Proportion of patients with reduced DLQI by five or more points and achieving DLQI of 0/1 reported by mNRI for all patients and LOCF for stratified patients. RZB: risankizumab; UST: ustekinumab; LOCF: last observation carried forward; OLE: open label extension; PASI: Psoriasis Area and Severity Index; DLQI: Dermatology Life Quality Index; mNRI: modified non-responder imputation.

For patients with an incomplete response (PASI 75 to <90), 64.2% had improved PASI scores after the first dose, 71.7% were improved after the second dose, and 75.5% were improved after seven doses compared to PASI score at time of switch (). Of the incomplete responders that improved their PASI score, 40% reached PASI 100, and 25% reached PASI 90 to <100 after one dose. These improvements were similar after two and seven doses (). After seven doses, no patient’s PASI score dropped below their response category (inadequate or incomplete) at the time of switch ().

Quality of life also improved for patients switching from UST to RZB. Prior to switching from UST to RZB, 74.9% (LOCF 85%) had achieved a DLQI reduction of ≥5 points compared to baseline in UltIMMa-1/2. After two doses of RZB, 86.0% (LOCF 98%) of patients achieved a DLQI reduction of ≥5 points compared to baseline in UltIMMa-1/2. A similar proportion of patients achieved a DLQI reduction of ≥5 points compared to baseline in UltIMMa-1/2 (). For patients switching from UST to RZB, prior to the first dose of RZB, 50.0% (mNRI, OC, and LOCF) of patients had achieved a DLQI status 0/1. After 2 doses of RZB, 75.6% (75.7% OC and LOCF) of patients had achieved a DLQI of 0/1. After 6 doses of RZB, 80.2% (81.2% by OC, 82.8% by LOCF) achieved a DLQI of 0/1.

For inadequate responders (PASI <75), prior to the switch from UST to RZB, 10% of patients had a DLQI of 0/1. Two doses of RZB increased this percentage to 57%, and after four and six doses, 63% of inadequate responders had a DLQI of 0/1. For incomplete responders (PASI 75 to <90), 45% of patients had a DLQI of 0/1 prior to switching from UST to RZB. A DLQI of 0/1 was achieved by 70% of patients after two doses, 68% after four doses, and 81% after six doses of RZB.

Safety

When compared with data from 52-week RZB treatment in UltIMMa-1 and -2, rates of treatment-emergent AEs were comparable for patients treated with RZB following the switch from UST without washout (). AEs were reported at 124.2 events per 100 patient years (PY). Eighteen serious AEs (6.2/100 PY) and 19 severe AEs (6.5/100 PY) were reported. Two serious infections occurred (0.7/100 PY). There were no AEs leading to death or hypersensitivities. A similar safety profile was seen for patients switching from ADA to RZB (Citation7). During the switch from ADA to RZB (week 16 to 44), four serious AEs, four severe AEs, and no deaths were reported (Citation7).

Table 2. Treatment-emergent adverse events during the LIMMitless study.

Discussion

Patients that switched to RZB from UST or ADA showed improvements in PASI responses and DLQI outcomes. Additionally, there were no significant safety events associated with switching patients to RZB without a washout period.

This analysis reflects a more “real-world” switch scenario without a washout period in patients who have failed to meet PASI treatment thresholds. In the clinical setting, it is not always apparent when to switch patients to a new treatment or what criteria best define when a patient may need a different treatment. In this analysis, there were no significant new safety signals despite the lack of washout period, and no patient demonstrated a worsening of their initial PASI response upon switch. Our analysis shows that patients switched to RZB did not lose their initial treatment response, providing clinical information on the relative benefit-risk of a switch in treatment. Switching treatments for patients with an inadequate response has also been explored between other IL-23 inhibitors, guselkemab and UST (Citation11).

Safety during treatment changes is an important consideration for clinicians and their patients. Published reports on the safety of RZB from 17 clinical trials, including those presented within this manuscript have shown that RZB demonstrated a favorable safety profile in both short- and long-term treatments (Citation12).

There are limitations inherent to this post-hoc analysis. Patients switched from UST to RZB in the single-arm, open-label extension and thus, there is no comparator for how patients do on continuous UST treatment compared to switching to RZB. However, our results still demonstrate a numerical improvement for patients after their switch. For the ADA to RZB switch population, a smaller patient population switched from ADA to RZB, and these patients had a shorter duration of follow-up. However, IMMvent directly assessed the switch from ADA to RZB compared to continuous ADA treatment in intermediate responders and was adequately powered to assess for superiority. In this direct comparator analysis, switching to RZB was superior for patients with an intermediate response than patients remaining on ADA after rerandomization (Citation7).

For patients with an inadequate or incomplete response to UST or ADA, switching to RZB improved PASI 90 and PASI 100 achievement and quality of life for patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis. Additionally, no patient’s PASI score dropped below their response category (inadequate or incomplete) at the time of switch, and no new significant safety risks were noted. These results are particularly impactful given the achievement of high treatment targets for patients. Clinicians may find that a patient’s quality of life and symptoms are improved by switching incomplete and inadequate responders to an alternative treatment option.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (112.9 KB)Acknowledgements

AbbVie and the authors thank all study investigators for their contributions and the patients who participated in this study. The authors would like to thank Kristian Reich for their contributions to the development of the manuscript outline. The authors would also like to thank Trisha A. Rettig. PhD, of AbbVie for medical writing support and Angela T. Hasdell of AbbVie for editorial support in production of this publication.

Disclosure statement

B Strober has served as a consultant (received honoraria) for AbbVie, Almirall, Amgen, Arcutis, Arena, Aristea, Asana, Boehringer Ingelheim, Immunic Therapeutics, Bristol Myers Squibb, Connect Biopharma, Dermavant, EPI Health, Evelo Biosciences, Janssen, Leo, Eli Lilly, Maruho, Meiji Seika Pharma, Mindera Health, Novartis, Ono, Pfizer, UCB Pharma, Sun Pharma, Regeneron, Sanofi-Genzyme, Union Therapeutics, Ventyxbio, vTv Therapeutics, has stock options with Connect Biopharma, Mindera Health, has served as a speaker for AbbVie, Eli Lilly, Incyte, Janssen, Regeneron, Sanofi-Genzyme, is a scientific co-director for CorEvitas (formerly Corrona) Psoriasis Registry, has served as an investigator for Dermavant, AbbVie, CorEvitas Psoriasis Registry, Dermira, Cara, Novartis, and received honorarium for serving as the Editor-In-Chief of the Journal of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis.

A Armstrong reported receiving grants and personal fees from AbbVie, Eli Lilly, Leo Pharma, and Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corp; personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim/Parexel, Bristol Myers Squibb, Celgene, Dermavant, Janssen Pharmaceuticals Inc, Merck, Modernizing Medicine, Ortho Dermatologics, Pfizer Inc, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Sanofi Genzyme, Science 37 Inc, Genentech, GlaxoSmithKline, and Valeant; and grants from Dermira, Janssen-Ortho Inc, Kyowa Hakko Kirin, and UCB Pharma outside the submitted work.

S Rubant, M Patel, T Wu, and H Photowala are full-time salaried employees of AbbVie and may own stock/options.

J Crowley has received research/grant support from AbbVie, Amgen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Janssen, Lilly, MC2 Therapeutics, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, Regeneron, Sandoz, Sanofi, Sun Pharma, UCB, and Verrica. He has served as a consultant for AbbVie, Amgen, Celgene, Dermira, Lilly, Novartis, Sun Pharma, and UCB; and has worked on speakers bureaus for AbbVie, Janssen, Lilly, Novartis, Regeneron, Sanofi, and UCB.

Data availability statement

AbbVie is committed to responsible data sharing regarding the clinical trials we sponsor. This includes access to anonymised, individual, and trial-level data (analysis data sets), as well as other information (eg, protocols and clinical study reports), as long as the trials are not part of an ongoing or planned regulatory submission. This includes requests for clinical trial data for unlicensed products and indications. This clinical trial data can be requested by any qualified researchers who engage in rigorous, independent scientific research, and will be provided following review and approval of a research proposal and statistical analysis plan and execution of a data sharing agreement. Data requests can be submitted at any time and the data will be accessible for 12 months, with possible extensions considered. For more information on the process, or to submit a request, visit the following link: https://www.abbvie.com/our-science/clinical-trials/clinical-trials-data-and-information-sharing/data-and-information-sharing-with-qualified-researchers.html.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Armstrong AW, Read C. Pathophysiology, clinical presentation, and treatment of psoriasis: a review. JAMA. 2020;323(19):1945–1960.

- Lebwohl MG, Bachelez H, Barker J, et al. Patient perspectives in the management of psoriasis: results from the population-based multinational assessment of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis survey. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70(5):871–881 e1-30.

- Elmets CA, Korman NJ, Prater EF, et al. Joint AAD-NPF guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with topical therapy and alternative medicine modalities for psoriasis severity measures. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84(2):432–470.

- Strober BE, van der Walt JM, Armstrong AW, et al. Clinical goals and barriers to effective psoriasis care. Dermatol Ther. 2019;9(1):5–18.

- Armstrong AW, Siegel MP, Bagel J, et al. From the medical board of the national psoriasis foundation: treatment targets for plaque psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76(2):290–298.

- Gordon KB, Strober B, Lebwohl M, et al. Efficacy and safety of risankizumab in moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis (UltIMMa-1 and UltIMMa-2): results from two double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled and ustekinumab-controlled phase 3 trials. Lancet. 2018;392(10148):650–661.

- Reich K, Gooderham M, Thaci D, et al. Risankizumab compared with adalimumab in patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis (IMMvent): a randomised, double-blind, active-comparator-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2019;394:576–586.

- Hongbo Y, Thomas CL, Harrison MA, et al. Translating the science of quality of life into practice: What do dermatology life quality index scores mean? J Invest Dermatol. 2005;125(4):659–664.

- Ryan C, Crowley J, Valdecantos W, et al. Discussed E-poster presentations. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2019;33(S3):20–44.

- Strober B, Eyerich K, Chih-Ho Hong H. editors. Long-term efficacy and safety of switching from ustekinumab to risankizumab: results from the open-label extension LIMMitless. P1714. 28th European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (EADV) Congress2019.

- Langley RG, Tsai TF, Flavin S, et al. Efficacy and safety of guselkumab in patients with psoriasis who have an inadequate response to ustekinumab: results of the randomized, double-blind, phase III NAVIGATE trial. Br J Dermatol. 2018;178(1):114–123.

- Gordon KB, Lebwohl M, Papp KA, et al. Long-term safety of risankizumab from 17 clinical trials in patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2022;186(3):466–475.