Abstract

Background

Methotrexate (MTX) is a systemic treatment for plaque-type psoriasis. At the time of approval, no dose-ranging studies were performed. Nowadays, a uniform dosing regimen is lacking. This might contribute to suboptimal treatment with the drug.

Objective

To summarize the literature involving the MTX dosing regimens in psoriasis patients.

Methods

In this SR, RCTs and documents with aggregated evidence (AgEv) on the MTX dosing regimen in psoriasis were summarized. All randomized controlled trials (RCTs) in which oral, subcutaneous or intramuscular MTX was used in patients with psoriasis and AgEv, were included. The MEDLINE, EMBASE and CENTRAL databases were searched up to June 20, 2022. This SR was registered in PROSPERO.

Results

Thirty-nine RCTs had a high risk of bias. Test dosages were given in only 3 RCTs. In the RCTs, MTX was usually prescribed in a start dose of 7.5 mg/week (n = 13). MTX was mostly given in a start dose of 15 mg/week, in the AgEv (n = 5). One guideline recommended a test dose, in other aggregated evidence a test dose was not mentioned or even discouraged.

Conclusions

There is a lack of high-quality evidence and available data for dosing MTX in psoriasis is heterogeneous.

Introduction

Methotrexate (MTX, a dihydrofolate reductase inhibitor), is a systemic treatment for psoriasis. (Citation1–3) The effectiveness and safety of this drug are acknowledged in guidelines and studies from around the world. (Citation4–6) Even in the era of biological treatments, MTX is an important drug, being globally available and relatively affordable. (Citation7)

Since the drug was approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) before dose ranging studies were performed, a uniform dosing regimen of MTX in psoriasis is lacking. In the first years of use, Rees et al. reported a daily dosage of 1.5–2 mg which should be administered for 3–12 days in a row. (Citation8) In 1969, a weekly oral dosage of 25 mg MTX was described by Roenigk et al. (Citation9) Three years later, Weinstein and Frost reported a three weekly divided dose in which 2.5–5 mg of the drug was administered every 12 h. (Citation10)

Also in clinical practice there is a wide variety in the different aspects related to MTX dosing, as can be concluded by a global survey from 2015 (Citation11) and a systematic review (SR) on the oral use of this drug in psoriasis (23 RCTs, 11 documents with aggregated evidence, search till September 2013) (Citation12). The variability in dosing regimens might contribute to suboptimal treatment with MTX or can lead to early discontinuation of treatment due to limited efficacy or side effects.

To give a summary of the available literature on this varying dosing and corresponding efficacy, effectiveness and safety, we present an update of our earlier performed SR (Citation12) in which RCTs and documents with aggregated evidence (AgEv, a term which was used for the included expert meetings, SRs with treatment recommendations and guidelines) were included. The inclusion criteria for RCTs from our earlier performed SR, which were limited to oral administration, were extended to oral, subcutaneous and intramuscular administration of MTX. The population selection criteria were extended from adult patients to adult and pediatric patients. This SR was the basis for a consensus process and served to identify future research projects.

Materials and methods

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

This systematic review (SR) was registered in PROSPERO (Citation13) with registration number CRD42022303486. The SR was reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for SRs and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) statement. (Citation14) We did not publish a protocol.

All randomized controlled trials (RCTs) in which oral, subcutaneous or intramuscular MTX was used in >10 adults or children with psoriasis (>75% chronic plaque psoriasis) were included. These inclusion criteria are extended compared to our earlier performed SR. We excluded RCTs in which no skin effectiveness outcome (e.g. PASI score) was reported, studies that used topical or intralesional MTX, duplicate publications, articles for which the full text was not available, or papers in languages other than Dutch, English, French or German.

For the aggregated evidence, all expert meetings, SRs with treatment recommendations and guidelines starting from 2010 that were found were included. We choose 2010 to include only most up to date expert meeting reports, SRs and guidelines, to prevent inclusion of outdated information.

Literature search

For RCTs and documents with AgEv, the MEDLINE, EMBASE and CENTRAL databases were searched up to June 20, 2022 by a clinical librarian. As a consequence of the extended inclusion criteria, the literature search was iterated from inception. The complete search strategy can be found in . We choose to select RCTs during the selection process, instead of adding specific RCT search terms to the search strategy.

Table 1. Search strategy for MEDLINE, EMBASE, and CENTRAL.

We searched TRIP (Citation15), the International Psoriasis Council (IPC) website (Citation16) and Skin Inflammation and Psoriasis International Network (SPIN) website (Citation17) (search date June 21, 2022) for documents with AgEv, complemented with guidelines known to the authors.

Study selection

The RCT search results were merged and duplicates were removed. Hereafter, two authors independently selected all articles for eligibility, taking the inclusion and exclusion criteria into account. Articles were screened based on title, abstract and full-text. A third author was consulted in case of disagreements.

As described above, apart from the year of publication, no specific exclusion criteria were used for the documents with AgEv.

Risk of bias assessment

The risk of bias of the RCTs was assessed by two authors using the revised risk of bias tool from Cochrane; ‘RoB 2′ (Citation18). This tool consists of five domains: randomization process, deviations from the intended interventions, missing outcome data, measurement of the outcome and selection of the reported result. We assessed the risk of bias for the primary efficacy outcomes of all studies.

For the documents with AgEv, no quality assessments were performed.

Data extraction

For the RCTs and documents with AgEv, data extraction was independently performed by two authors and collected on predefined data-extraction forms. Collected study characteristics for RCTs and -when available- documents with AgEv, included: publication date, number of patients, age, gender, previous treatments, concomitant medication, duration of treatment, duration of follow-up, outcome tool used, efficacy (skin outcome, e.g. PASI score), time to effect, duration of remission, side-effects and serious side-effects. On dosing regimen the data collection for RCTs and -when available- documents with AgEv involved: test dose (a dose was included as test dose, when the authors named this accordingly), start dose, maintenance dose, dose adjustments like increasing and decreasing the dose, maximum weekly dose, whether there is a maximum cumulative dose, whether treatment was stopped in case of efficacy, route of administration, dosing scheme, whether the route of administration was switched because of lack of effect, whether the route of administration was switched because of side-effects and the use and dosing regimen of folic acid. Data on the different aspects of the dosing regimen were collected for adults and children separately.

Meta-Analysis

If the included RCTs were clinically (e.g. dosing schemes) and methodologically (e.g. outcome measurements) homogeneous and had a low risk of bias, a meta-analysis of the used MTX dosing (start dose or maintenance dose) in relation to the efficacy outcomes (PASI score or other skin outcome) was performed. If the studies were not homogeneous, data pooling was not possible.

Results

Study selection

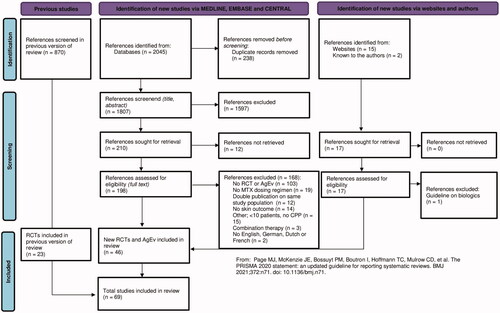

summarizes the selection process. The update from the literature search identified 2045 references of which 46 references (22 RCTs and 24 documents with AgEv; expert meetings, SRs with treatment recommendations and guidelines) were included. In the 45 RCTs in total (earlier performed SR and update), 5350 patients were randomized. Only one RCT involved children. Most RCTs compared MTX to another treatment (n = 41), 4 studies compared two different MTX dosing regimens. In these studies, MTX 7.5 mg/week vs. MTX 15 mg/week (Citation19,Citation20), MTX 10 mg/week vs. MTX 25 mg/week (Citation21) and MTX 2.5 mg 6 days/week vs. MTX 15 mg/week were investigated (Citation22).

Data extraction

See for different aspects on dosing regimens and efficacy of the included RCTs. Since the inclusion criteria for this update SR were extended, we iterated the data-extraction for the RCTs from our earlier performed SR. See for details on dosing regimens of the documents with AgEv. In Table S1a all details on the characteristics of the included references can be found. See Table S1b for all extracted data involving the MTX dosing regimen. All four tables are separated for adults and children. Salient results from the RCTs and documents with AgEv per dosing item can be found below.

Table 2. Dosing regimens and efficacy from the included RCTsa.

Table 3. Dosing regimens from included aggregated evidence.

Meta-Analysis

As a consequence of the many dosing regimens included (differences in start-dose, dosing regimen, adjustments in dosing, and folic acid dosing) and the diversity in outcome reporting (PASI in many ways and at different time-points), the studies were clinically and methodologically heterogeneous. Therefore, no data was pooled in a meta-analysis.

Risk of bias in the RCTs

According to the Cochrane RoB 2 Tool, 39 RCTs had a high risk of bias, indicating a low quality of evidence. Four studies had a low overall risk of bias (Citation23–26), for two studies there were only some concerns (Citation27,Citation28). See for details on the RoB.

Table 4. Risk of Bias assessment of included RCTs.

Test dose

A MTX test dose can be given to detect early toxic effects, e.g. idiosyncratical bone marrow failure. (Citation29) Three RCTs used a test dose. In a study from Fallah Arani et al. (Citation30), the test dose was 5 mg/week. Lab controls were performed three days and one week after start. Hereafter, gradually dose increase was possible. In a RCT from Soliman et al. (Citation31), a test dose of 7.5 mg in a three divided dose was prescribed, gradually increasing the dose by 5 mg/week in the next weeks until the effective dose was achieved. In a recent RCT from Verma et al. (Citation28) a test dose of 2.5 mg was given, patients were observed 48 h for any side effects. Hereafter, a start dose of 15 mg/week was given.

One recent guideline from 2020 (Citation5), recommended the use of a test dose in elderly and patients with relative contra-indications. The remaining documents with AgEv do not mention a test dose, or even discourage it. (Citation4,Citation32)

Start dose and maintenance dose

In the 45 RCTs, 7.5 mg/week was usually the starting dosage (n = 13 (Citation20,Citation24,Citation27,Citation30,Citation33–40)). A specific maintenance dose was not reported, although some studies did not change the MTX dosing after start, see also .

The efficacy of the different start doses could not be compared, since the included studies used different outcomes on different time points. Besides, the definition of efficacy was varying: it involved for example the number of patients that achieved PASI50 on week 4 (Citation38) and week 8 (Citation41) or the achievement of PASI75 without a specific time point (Citation42).

A few studies used comparable outcomes. After 12 weeks, we found a mean percentage of patients with 7.5 mg/week that achieved a PASI75, of 39.1%. (Citation30,Citation33,Citation35,Citation39,Citation43) For 15 mg/week, this percentage was 75%. (Citation44) See also .

Table 5. Mean percentage of patients that achieved PASI75 from included RCTs at week 8, week 12 and week 16a.

In the documents with AgEv, advised ranges were 5–15 mg/week, (Citation45,Citation46), 7.5–15 mg/week (Citation47) or 15–25 mg/week (Citation32). The dosage could be based on individual factors. The most frequently advised start dose was 15 mg/week (n = 5 (Citation4,Citation6,Citation32,Citation48,Citation49)). A specific maintenance dose was not reported.

Dose adjustments

Thirteen studies (Citation19–22,Citation34,Citation39,Citation44,Citation50–55) prescribed MTX according to a fixed dosing scheme. Pre-defined dosing regimens involved dose adjustments on settled time points in 5 studies (Citation24,Citation43,Citation56–58) or a set dose increase of 2.5 mg per 2 weeks in one study (Citation59). Ten studies based their dose adjustments on clinical efficacy (Citation12,Citation23,Citation25,Citation31,Citation38,Citation41,Citation42,Citation60–63). Lajevardi et al. (Citation27,Citation37) used the BMI from their patients to adjust the MTX dosages. In children, one RCT based their dose adjustments on efficacy (Citation26), and one guideline on concentration-time profiles (Citation64).

Five documents with AgEv advised to base the dose adjustments on clinical response (Citation4,Citation45,Citation64–66). In the British Association of Dermatology guideline, no dose adjustments were advised and it was recommended to switch to subcutaneous administration or another treatment, in case of clinical inefficacy of MTX. (Citation67)

Administration forms

In the included RCTs, MTX was primarily administered orally (n = 35). MTX was administered orally or subcutaneously in two RCTs (Citation25,Citation63) or with injections (not reported whether they were subcutaneous or oral) in another study (Citation68). We found one RCT (Citation63) investigating the difference in efficacy between oral and subcutaneous administration. In this RCT from Choonhakarn et al. (Citation63), similar effects in PASI score improvements were found. This is in contrast with a controlled clinical trial from 2019, where the subcutaneous administration of MTX showed significant better PASI reduction compared to oral administration. (Citation69) As this study was no RCT, it was not included in our SR.

In 5 documents with AgEv (Citation6,Citation45,Citation61,Citation64,Citation70), the authors recommended to start the administration of MTX subcutaneously. In 4 documents with AgEv, MTX could be started subcutaneously or orally. (Citation4,Citation47,Citation66,Citation71,Citation72) In 5 other documents with AgEv, even IM (Citation32,Citation46,Citation48,Citation73) or IV (Citation46,Citation74) administration was mentioned as administration option, next to oral or subcutaneous administration. In 9 documents with AgEv, no recommendation for a specific administration form was given. (Citation12,Citation65,Citation67,Citation73,Citation75–78)

Dosing schedule

Twenty-six RCTs (Citation21,Citation23–25,Citation27,Citation28,Citation31,Citation33,Citation39,Citation41,Citation42,Citation50–53,Citation55–57,Citation60,Citation68,Citation79–84) prescribed MTX in a once weekly dosing schedule. Other schedules used were: Weinstein schedules (n = 7) (Citation20,Citation30,Citation34,Citation35,Citation43,Citation58,Citation62), weekly divided schedules (n = 3) (Citation37,Citation40,Citation54) or combinations of different dosing schedules (n = 5) (Citation19,Citation22,Citation38,Citation63,Citation85). In the remaining articles the dosing schedule was not reported.

Three recent documents with AgEv (Citation6,Citation64,Citation70), recommended a once weekly dosing schedule. The other documents with AgEv reported a weekly dose (Citation32,Citation45,Citation48,Citation64,Citation65,Citation67,Citation73) or a combination of weekly and weekly divided dose (Citation4,Citation47,Citation74). The remaining documents with AgEv did not mention the dosing schedule in their recommendations (Citation46,Citation61,Citation66,Citation72,Citation75–78,Citation86).

Maximum dose

The maximum dosage of MTX differed among the RCTs: in 7 studies (Citation28,Citation30,Citation35,Citation37,Citation66,Citation84) a dose of 15 mg/week was reported, and in 2 studies (Citation6,Citation70) the maximum dosage was 20 mg/week (25 mg/week in individual cases). Other reported maximum dosages were 25 mg/week (Citation25,Citation36,Citation63,Citation64), 25–30 mg/week (Citation45) or 30 mg/week (Citation4,Citation31,Citation38,Citation46,Citation47,Citation62,Citation65).

The maximum dose of MTX was 20 mg/week (Citation45,Citation87), 25 mg/week (Citation12,Citation64) or 30 mg/week (Citation4,Citation47,Citation65) in the documents with AgEv. In one guideline, the maximum dose of MTX was 15 mg/week (Citation66). The other 16 documents with aggregated evidence did not report a specific maximum dose.

Cumulative dose

Except for three RCTs (Citation31,Citation84,Citation88), in which a cumulative dose was only reported without clinical consequences, the cumulative dosage of MTX was not mentioned in the included RCTs.

In one guideline from 2010 (Citation47), a specific MTX cumulative dose was reported. In this guideline, it is stated that dermatology patients have more issues with hepatotoxicity, probably due to confounding factors as nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. The authors stated that the cumulative dose for patients without these comorbidities can be increased from 1–1.5 gram to 3.5–4 gram. In the other documents with AgEv the use of a cumulative dose was not described.

Use of folic acid

Thirty-six studies (Citation4,Citation6,Citation12,Citation21,Citation23–25,Citation30–33,Citation35,Citation37–39,Citation43,Citation45,Citation46,Citation50,Citation51,Citation56,Citation57,Citation59,Citation63–67,Citation70,Citation72–74,Citation76,Citation79,Citation82,Citation85,Citation86,Citation88) used folic acid supplementation and in 4 studies (Citation22,Citation58,Citation62,Citation81) no folate was prescribed. The remaining studies did not mention the use of folic acid. Most authors recommended the daily use of 1 mg folic acid (Citation27,Citation37,Citation43,Citation59) or the weekly use of 5 mg folic acid (Citation23,Citation24,Citation35,Citation38,Citation57,Citation63).

In the Dutch guideline (Citation4) it is advised to increase the dosage of folic acid to 10 mg/week when ≥15 mg/week of MTX is prescribed. This was based on recommendations from rheumatologists in the guideline working group.

Safety

In the RCTs frequently described side effects were elevated liver enzymes in (18 RCTs) (Citation21,Citation22,Citation24,Citation25,Citation30,Citation35,Citation37,Citation39,Citation40,Citation42,Citation43,Citation52,Citation57,Citation62,Citation63,Citation79,Citation82,Citation88), headache (14 RCTs) (Citation22–25,Citation34,Citation35,Citation37–39,Citation42,Citation57,Citation63,Citation79,Citation83,Citation85,Citation88) and GI-complaints (30 RCTs) (Citation21–25,Citation28,Citation31,Citation33–35,Citation37–39,Citation42,Citation43,Citation50,Citation52,Citation54,Citation56–58,Citation60,Citation62,Citation63,Citation81,Citation83–85,Citation88). Serious side effects that were mentioned were strong elevated liver enzymes (Citation53), severe nausea (Citation53), serious infections (Citation79) laboratory adverse effects leading to exclusion (anemia, thrombocytopenia, elevated liver enzymes, increase of creatinine, or hypertension) (Citation83), and unknown serious side effects (Citation23,Citation24,Citation26,Citation57). Fourteen RCTs (Citation22,Citation33,Citation35,Citation39,Citation42,Citation43,Citation50,Citation52,Citation54,Citation56,Citation58,Citation60,Citation62,Citation85) stated there were no serious adverse events, in the 20 remaining studies the occurrence of serious side effects was not reported. Details on safety information can be found in .

Discussion

Since the registration of MTX by the FDA, dermatologists have gained a large quantity of experience with this drug and it has been extensively studied in RCTs and observational studies. Our SR summarizes articles in which different aspects of dosages, dosage schedules and the use of folic acid are studied in psoriasis.

The starting dosage frequently advised in the RCTs and documents with AgEv was 7.5 mg/week and 15 mg/week, respectively. Most included studies reported a weekly dosing schedule in which MTX was administered orally. No papers were found supporting the use of a Weinstein schedule or a weekly divided schedule over a weekly administration schedule. The majority prescribed a maximum MTX dose of 15 mg/week or 30 mg/week. The use of folic acid might be beneficial, although this has not been studied in a randomized controlled study. The dosage however, is controversial (Citation88–90), and is mostly 1 mg/day or 5 mg/week. Safety data found in the included RCTs is in line with the AEs described in AgEv.

It is not possible to give recommendations on the most efficient and safe dosing regimen of MTX in psoriasis, since the quality of the literature is low, with only four studies with a low risk of bias (Citation23–26). One of those studies was the RCT from Reich (Citation23) et al. in which 36.2% of the patients achieved a PASI75 score after 12 weeks. Patients were treated with a dosage of 5 mg in week 0, 10 mg in week 1 and 15 mg from week 2, with further increase of the dose based on clinical response. Another high quality study, namely from Saurat (Citation57) et al., reported that 35.5% of the patients achieved PASI75 after 12 weeks. Patients started with 7.5 mg, received 10 mg in week 2–3 and 15 mg in week 4–7. Based on the efficacy of the drug, MTX dosages could be increased with 5 mg if < PASI50 at week 8 or week 12. Warren (Citation25) et al. presented a PASI75 response in 37 patients after 16 weeks. Patients were treated with 5–15 mg/week or 2.5–5 mg/week in case of renal impairment. The last high quality study was from Papp (Citation26) et al. They presented a mean PASI reduction of 13 in pediatric and adolescent patients treated with 0.1 mg/kg/week (up to 7.5 mg/kg/week) MTX. The dosage could be titrated upwards according to response or downwards in case of intolerance.

Strengths and limitations

To the best of our knowledge, this update is the first study summarizing the literature on the MTX dosing regimens in psoriasis patients including studies with oral, subcutaneous and intramuscular administration of the drug.

The extended inclusion criteria for the administration forms of MTX make this study of interest for daily practice. The addition of the subcutaneous administration form to the inclusion criteria, is of special importance for the prescription of MTX in Europe, since the recent European Dermatology Forum (EDF) guideline (Citation6) advised to start with subcutaneous administered MTX. In the EDF guideline, the primary administration of the subcutaneous form of MTX was advised due to safety risks, since the use of oral tablets had a higher risks for overdosing. In this SR, we did not find any RCTs in which the subcutaneous administration of MTX is compared to orally prescribed tablets.

Another strength of this study is the complete and recent overview of the risk of bias of the included studies, which is a consequence of the use of the most recent Cochrane Risk of Bias tool.

A limitation is the narrowing of our SR in the selection of RCTs and documents with AgEv. We excluded case reports and case series to prevent the development of an overly extensive SR. The inclusion criterion of 75% of the patients with CPP is a limitation as well. Based on a preparatory literature search we expected to oversight studies if we would narrow our SR to studies with a 100% of patients with CPP. The inclusion criterion of a minimum of 10 patients was chosen arbitrarily to reduce the chance of missing small RCTs.

Another limitation is the selection of languages that were considered; only studies in Dutch, English, French and German were included. This decision was made, since the authors were not able to extract data from studies written in other languages.

Clinical implications and future perspective

Our consensus study (Citation91) and this SR are a first step to optimize the treatment of psoriasis patients with MTX. However, our consensus should be supported with more evidence. High-quality RCTs or observational studies (e.g. cohort studies) comparing different dosing regimens of MTX are needed, especially for subpopulations as children.

Based on the literature included in this SR we performed a previously published consensus project (Citation91), resulting in the following recommendations for daily practice: a test dose may not be needed in adults, children and vulnerable patients (elderly, patients with renal insufficiency). The start dose of MTX could be 15 mg/week, 10 mg/m2/week in children and 7.5–15 mg/week in vulnerable patients. MTX can be administered once a week. The maximum weekly dose of MTX is 25 mg/week in adults and vulnerable patients and 15 mg/m2/week in children. Start with the administration of MTX in oral tablets, a switch to the subcutaneous form can be made in case of inefficacy or gastro-intestinal adverse events. Folic acid should be supplemented in all patients once a week and at least 24 h after MTX intake. Since the dosage of folic acid depends on prescription habits and the available evidence is controversial, no recommendations on dosage of folic acid can be made. (Citation91)

In future research, focus could lay on the use of folic acid for which the evidence is still quite controversial and depends on habits and local availability. (Citation91)

Other knowledge gaps involve the administration forms of MTX: in a low-quality study (Citation69) not included in this SR, we found indications that the subcutaneous administration form of the drug might be more effective. (Citation69)

Although there is no financial incentive for pharmaceutical companies to perform studies with MTX, the drug is used for many diseases in dermatology. It is, for example, prescribed off-label in alopecia areata, atopic dermatitis and morphea. (Citation92) Unfortunately, experience from the past has taught that dosing mistakes can result in fatal outcomes. (Citation93) Since MTX remains a significant and relatively affordable drug in the treatment of psoriasis patients in western and non-western countries, we should keep a future research focus on MTX.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (293.5 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors thanks clinical librarians Jacqueline Limpens and Nerissa Denswil for their advice on the design of the search strategy and for performing the search in MEDLINE, CENTRAL and EMBASE.

Disclosure statement

AH is involved as sub-investigator in clinical trials and observational studies from Abbvie, Janssen, LeoPharma, Lilly, Sanofi and UCB. RS, AC and SM report no conflict of interest. PS has done consultancies in the past for Sanofi 111017 and AbbVie 041217 (unpaid), receives departmental independent research grants for TREAT NL registry, for which she is Chief Investigator (CI), from pharma companies since December 2019, is involved in performing clinical trials with many pharmaceutical industries that manufacture drugs used for the treatment of e.g. psoriasis and atopic dermatitis, for which financial compensation is paid to the department/hospital.

References

- Gubner R, August S, Ginsberg V. Therapeutic suppression of tissue reactivity. II. Effect of aminopterin in rheumatoid arthritis and psoriasis. Am J Med Sci. 1951;221(2):176–182.

- Edmundson WF, Guy WB. Treatment of psoriasis with folic acid antagonists. AMA Arch Derm. 1958;78(2):200–203.

- Said S, Jeffes EW, Weinstein GD. Methotrexate. Clin Dermatol. 1997;15(5):781–797.

- Van Der Kraaij GE, Spuls Ph I, Balak DMW, et al. Update richtlijn psoriasis 2017. [dutch]. Nederlands Tijdschrift Voor Dermatologie en Venereologie. 2017;274:170–173.

- Menter A, Gelfand JM, Connor C, et al. Joint American academy of Dermatology-National psoriasis foundation guidelines of care for the management of psoriasis with systemic nonbiologic therapies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82(6):1445–1486.

- Mrowietz U, Nast A. The EuroGuiDerm Guideline for the systemic treatment of psoriasis vulgaris - 1.4 Methotrexate (MTX). European Dermatology Forum; 2021. https://www.edf.one/dam/jcr:299d47a3-617b-4981-8d3c-f57370da0898/8_Methotrexate_Oct_2021.pdf

- Methotrexate Prices, Coupons and Patient Assistance Programs. 2022. https://www.drugs.com/price-guide/methotrexate2022

- Rees RB, Bennett JH, Bostick WL. Aminopterin for psoriasis. AMA Arch Derm. 1955;72(2):133–143.

- Roenigk HH, Jr., Fowler-Bergfeld W, Curtis GH. Methotrexate for psoriasis in weekly oral doses. Arch Dermatol. 1969;99(1):86–93.

- Weinstein GD, Frost P. Methotrexate for psoriasis. A new therapeutic schedule. Arch Dermatol. 1971;103(1):33–38.

- Gyulai R, Bagot M, Griffiths CE, et al. Current practice of methotrexate use for psoriasis: results of a worldwide survey among dermatologists. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29(2):224–231.

- Menting SP, Dekker PM, Limpens J, et al. Methotrexate dosing regimen for plaque-type psoriasis: a systematic review of the use of test-dose, start-dose, dosing scheme, dose adjustments, maximum dose and folic acid supplementation. Acta Derm Venereol. 2016;96(1):23–28.

- PROSPERO. 2022. PROSPERO: international prospective register of systematic reviews: Centre for reviews and dissemination. York, UK: University of York.

- Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2021;10(1):89.

- Trip. Trip medical database. 2022. https://www.tripdatabase.com/

- IPC. International Psoriasis Council website. 2022. https://www.psoriasiscouncil.org/2022.

- SPIN. Skin inflammation & psoriasis international network website. 2022. https://www.spindermatology.org/

- Sterne JAC, Savović J, Page MJ, et al. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2019;366:l4898.

- Chladek J, Grim J, Martinkova J, et al. Low-dose methotrexate pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics in the therapy of severe psoriasis. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2005;96(3):247–248.

- Chladek J, Grim J, Martinkova J, et al. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of low-dose methotrexate in the treatment of psoriasis. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2002;54(2):147–156.

- Dogra S, Krishna V, Kanwar AJ. Efficacy and safety of systemic methotrexate in two fixed doses of 10 mg or 25 mg orally once weekly in adult patients with severe plaque-type psoriasis: a prospective, randomized, double-blind, dose-ranging study. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2012;37(7):729–734.

- Radmanesh M, Rafiei B, Moosavi ZB, et al. Weekly vs. daily administration of oral methotrexate (MTX) for generalized plaque psoriasis: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Int J Dermatol. 2011;50(10):1291–1293.

- Reich K, Langley RG, Papp KA, et al. A 52-week trial comparing briakinumab with methotrexate in patients with psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(17):1586–1596.

- Saurat JH, Stingl G, Dubertret L, et al. Efficacy and safety results from the randomized controlled comparative study of adalimumab vs. methotrexate vs. placebo in patients with psoriasis (CHAMPION). Br J Dermatol. 2008;1583:558–566.

- Warren RB, Mrowietz U, von Kiedrowski R, et al. An intensified dosing schedule of subcutaneous methotrexate in patients with moderate to severe plaque-type psoriasis (METOP): a 52 week, multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2017;389(10068):528–537.

- Papp K, Thaci D, Marcoux D, et al. Efficacy and safety of adalimumab every other week versus methotrexate once weekly in children and adolescents with severe chronic plaque psoriasis: a randomised, double-blind, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2017;390(10089):40–49.

- Lajevardi V, Kashiri A, Ghiasi M, et al. Evaluating the efficacy of ursodeoxycholic acid plus methotrexate vs methotrexate alone in the treatment of moderate to severe plaque-type psoriasis: a randomized clinical trial. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33(4):e13455.

- Verma KK, Kumar P, Bhari N, et al. Azathioprine weekly pulse versus methotrexate for the treatment of chronic plaque psoriasis: a randomized controlled trial. IJDVL. 2021;87:509–514.

- Roenigk HH, Jr., Auerbach R, Maibach H, et al. Methotrexate in psoriasis: consensus conference. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;38(3):478–485.

- Fallah Arani S, Neumann H, Hop WC, et al. Fumarates vs. methotrexate in moderate to severe chronic plaque psoriasis: a multicentre prospective randomized controlled clinical trial. Br J Dermatol. 2011;164(4):855–861.

- Soliman A, Nofal EA, Nofal A, et al. Combination therapy of methotrexate plus NBUVB phototherapy is more effective than methotrexate monotherapy in the treatment of chronic plaque psoriasis. J Dermatolog Treat. 2015;26(6):528–534.

- Rademaker M, Gupta M, Andrews M, et al. The australasian psoriasis collaboration view on methotrexate for psoriasis in the australasian setting. Australas J Dermatol. 2017;58(3):166–170.

- Abidi A, Rizvi D, Saxena K, et al. The evaluation of efficacy and safety of methotrexate and pioglitazone in psoriasis patients: a randomized, open-labeled, active-controlled clinical trial. Indian J Pharmacol. 2020;52(1):16–22.

- Ali ME, Rahman GMM, Akhtar N, et al. Efficacy and safety of leflunomide in the treatment of plaque type psoriasis. J Pak Assoc Dermatol. 2009;191:18–22.

- Flytstrom I, Stenberg B, Svensson A, et al. Methotrexate vs. ciclosporin in psoriasis: effectiveness, quality of life and safety. A randomized controlled trial. Br J Dermatol. 2008;158(1):116–121.

- Gordon KB, Betts KA, Sundaram M, et al. Poor early response to methotrexate portends inadequate long-term outcomes in patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis: evidence from 2 phase 3 clinical trials. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77(6):1030–1037.

- Lajevardi V, Hallaji Z, Daklan S, et al. The efficacy of methotrexate plus pioglitazone vs. methotrexate alone in the management of patients with plaque-type psoriasis: a single-blinded randomized controlled trial. Int J Dermatol. 2015;54(1):95–101.

- Reich K, Augustin M, Thaci D, et al. A 24-week multicentre, randomised, open-label, parallel-group study comparing the efficacy and safety of ixekizumab to fumaric acid esters and methotrexate in patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis naive to systemic treatment. Br J Dermatol. 2020;182(4):869–879.

- Yan H, Tang M, You Y, et al. Treatment of psoriasis with recombinant human LFA3-antibody fusion protein: a multi-center, randomized, double-blind trial in a chinese population. Eur J Dermatol. 2011;21(5):737–743.

- Tam HTX, Thuy LND, Vinh NM, et al. The combined use of metformin and methotrexate in psoriasis patients with metabolic syndrome. Dermatol Res Pract. 2022;2022:1–7.

- Reich K, Puig L, Paul C, TRANSIT Investigators, et al. One-year safety and efficacy of ustekinumab and results of dose adjustment after switching from inadequate methotrexate treatment: the TRANSIT randomized trial in moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2014;170(2):435–444.

- Sandhu K. e psoriasis. Abstract 1277 international investigative dermatology. The 4th joint meeting of the ESDR, japanese SID & SID, 30th april-4thMay 2003, Florida, USA. J Invest Dermatol. 2003;1211:213. Efficacy and safety of cyclosporine versus methotrexate in sever

- Akhyani M, Chams-Davatchi C, Hemami MR, et al. Efficacy and safety of mycophenolate mofetil vs. methotrexate for the treatment of chronic plaque psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010;24(12):1447–1451.

- Gupta SK, Dogra A, Kaur G. Comparative efficacy of methotrexate and hydroxyurea in treatment of psoriasis. J Pak Assoc Dermatol. 2005;153:247–251.

- Raaby L, Zachariae C, Ostensen M, et al. Methotrexate use and monitoring in patients with psoriasis: a consensus report based on a danish expert meeting. Acta Derm Venereol. 2017;97(4):426–432.

- Armstrong AW, Aldredge L, Yamauchi PS. Managing patients with psoriasis in the busy clinic: Practical tips for health care practitioners. J Cutan Med Surg. 2016;20(3):196–206.

- Carretero G, Puig L, Dehesa L, Grupo de Psoriasis de la AEDV, et al. Guidelines on the use of methotrexate in psoriasis. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2010;101(7):600–613. [

- Raboobee N, Aboobaker J, Jordaan HF, Working Group of the Dermatological Society of South Africa, et al. Guideline on the management of psoriasis in South Africa. S Afr Med J. 2010;100(4 Pt 2):257–282.

- Barker J, Horn EJ, Lebwohl M, International Psoriasis Council, et al. Assessment and management of methotrexate hepatotoxicity in psoriasis patients: Report from a consensus conference to evaluate current practice and identify key questions toward optimizing methotrexate use in the clinic. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25(7):758–764.

- Bhuiyan MSI, Sikder MA, Rashid MM, et al. Role of oral colchicine in plaque type psoriasis. A randomized clinical trial comparing with oral methotrexate. J Pak Assoc Dermatol. 2010;203:146–151.

- El-Eishi NH, Kadry D, Hegazy RA, et al. Estimation of tissue osteopontin levels before and after different traditional therapeutic modalities in psoriatic patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27(3):351–355.

- Gupta R, Gupta S. Methotrexate-betamethasone weekly oral pulse in psoriasis. J Dermatolog Treat. 2007;18(5):291–294.

- Malik T, Ejaz A. Comparison of methotrexate and azathioprine in the treatment of psoriasis: a randomized controlled trial. J Pak Assoc Dermatol. 2010;203:152–157.

- Shehzad T, Dar NR, Zakria M. Efficacy of concomitant use of PUVA and methotrexate in disease clearance time in plaque type psoriasis. J Pak Med Assoc. 2004;54(9):453–455.

- Karapetyan S, Davtyan H, Khachikyan K, et al. Impact of supplemental essential phospholipids on treatment outcome and quality of life of patients with psoriasis with moderate severity. Dermatol Ther. 2022;35(4):e15335.

- Gumusel M, Ozdemir M, Mevlitoglu I, et al. Evaluation of the efficacy of methotrexate and cyclosporine therapies on psoriatic nails: a one-blind, randomized study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;259:1080–1084.

- Saurat JH, Langley RG, Reich K, et al. Relationship between methotrexate dosing and clinical response in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis: subanalysis of the CHAMPION study. Br J Dermatol. 2011;165(2):399–406.

- Heydendael VM, Spuls PI, Opmeer BC, et al. Methotrexate versus cyclosporine in moderate-to-severe chronic plaque psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(7):658–665.

- Choi CW, Kim BR, Seo E, et al. The objective psoriasis area and severity index: a randomized controlled pilot study comparing the effectiveness of ciclosporin and methotrexate. Br J Dermatol. 2017;177(6):1740–1741.

- Ranjan N, Sharma NL, Shanker V, et al. Methotrexate versus hydroxycarbamide (hydroxyurea) as a weekly dose to treat moderate-to-severe chronic plaque psoriasis: a comparative study. J Dermatolog Treat. 2007;18(5):295–300.

- Mrowietz U, de Jong EM, Kragballe K, et al. A consensus report on appropriate treatment optimization and transitioning in the management of moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014;28(4):438–453.

- Ho SG, Yeung CK, Chan HH. Methotrexate versus traditional chinese medicine in psoriasis: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial to determine efficacy, safety and quality of life. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2010;35(7):717–722.

- Choonhakarn C, Chaowattanapanit S, Julanon N, et al. Comparison of the clinical efficacy of subcutaneous vs. oral administration of methotrexate in patients with psoriasis vulgaris: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2022;47(5):942–948.

- Menter A, Cordoro KM, Davis DMR, et al. Joint American academy of Dermatology-National psoriasis foundation guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis in pediatric patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82(1):161–201.

- Mijuskovic ZP, Kandolf-Sekulovic L, Tiodorovic D, et al. Serbian association of dermatovenereologists’ guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of psoriasis. Serb J Dermatol Venereol. 2016;82:61–78.

- Amatore F, Villani AP, Tauber M, Psoriasis Research Group of the French Society of Dermatology (Groupe de Recherche sur le Psoriasis de la Société Française de Dermatologie), et al. French guidelines on the use of systemic treatments for moderate-to-severe psoriasis in adults. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2019;33(3):464–483.

- Warren RB, Weatherhead SC, Smith CH, et al. British association of dermatologists’ guidelines for the safe and effective prescribing of methotrexate for skin disease 2016. Br J Dermatol. 2016;175(1):23–44.

- El-Hanafy GM, El-Komy MHM, Nashaat MA, et al. The impact of methotrexate therapy with vitamin D supplementation on the cardiovascular risk factors among patients with psoriasis; a prospective randomized comparative study. J Dermatol Treat. 2022;33(3):1617–1622.

- Attwa EM, Elkot RA, Abdelshafey AS, et al. Subcutaneous methotrexate versus oral form for the treatment and prophylaxis of chronic plaque psoriasis. Dermatol Ther. 2019;32(5):e13051.

- Nast A, Altenburg A, Augustin M, et al. German S3-Guideline on the treatment of psoriasis vulgaris, adapted from EuroGuiDerm - Part 1: Treatment goals and treatment recommendations. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2021;19(6):934–150.

- Tangtatco JAA, Lara-Corrales I. Update in the management of pediatric psoriasis. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2017;29(4):434–442.

- Kolios AGA, Yawalkar N, Anliker M, et al. Swiss S1 guidelines on the systemic treatment of psoriasis vulgaris. Dermatology. 2016;232(4):385–406.

- Gisondi P, Altomare G, Ayala F, et al. Italian guidelines on the systemic treatments of moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31(5):774–790.

- Kalb RE, Strober B, Weinstein G, et al. Methotrexate and psoriasis: 2009 national psoriasis foundation consensus conference. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60(5):824–837.

- Arnone M, Takahashi MDF, Carvalho AVE, et al. Diagnostic and therapeutic guidelines for plaque psoriasis - Brazilian society of dermatology. An Bras Dermatol. 2019;94(2 Suppl 1):76–107.

- Papp K, Gulliver W, Lynde C, et al. Canadian guidelines for the management of plaque psoriasis: overview. J Cutan Med Surg. 2011;15(4):210–219.

- Dauden E, Puig L, Ferrandiz C, the Spanish Psoriasis Group of the Spanish Academy of Dermatology and Venereology, et al. Consensus document on the evaluation and treatment of moderate-to-severe psoriasis: Psoriasis group of the spanish academy of dermatology and venereology. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30(Supplement 2):1–18.

- Samarasekera E, Sawyer L, Parnham J, Guideline Development Group, et al. Assessment and management of psoriasis: summary of NICE guidance. BMJ. 2012;345:e6712.

- Barker J, Hoffmann M, Wozel G, et al. Efficacy and safety of infliximab vs. methotrexate in patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis: results of an open-label, active-controlled, randomized trial (RESTORE1). Br J Dermatol. 2011;165(5):1109–1117.

- Revicki D, Willian MK, Saurat JH, et al. Impact of adalimumab treatment on health-related quality of life and other patient-reported outcomes: results from a 16-week randomized controlled trial in patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2007;158(3):549–557.

- de Jong EM, Mork NJ, Seijger MM, et al. The combination of calcipotriol and methotrexate compared with methotrexate and vehicle in psoriasis: results of a multicentre placebo-controlled randomized trial. Br J Dermatol. 2003;148(2):318–325.

- Yousefzadeh H, Azad FJ, Banihashemi M, et al. Clinical efficacy and quality of life under micronutrients in combination with methotrexate therapy in chronic plaque of psoriatic patients. Dermatol Sinica. 2017;35(4):187–194.

- Singh SK, Singnarpi SR. Safety and efficacy of methotrexate (0.3 mg/kg/week) versus a combination of methotrexate (0.15 mg/kg/week) with cyclosporine (2.5 mg/kg/day) in chronic plaque psoriasis: a randomised non-blinded controlled trial. IJDVL. 2021;87:214–222.

- Banerjee S, Das S, Roy A, et al. Comparative effectiveness and safety of methotrexate Versus PUVA in severe chronic stable plaque psoriasis. Indian J Dermatol. 2021;664:371–377.

- Chladek J, Simkova M, Vaneckova J, et al. The effect of folic acid supplementation on the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of oral methotrexate during the remission-induction period of treatment for moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2008;644:347–355.

- Echeverría C, Kogan N, Stengel FM, et al. Argentine guidelines for the systemic treatment of moderate to severe psoriasis in adult patients. 2021.

- Nast A, Altenburg A, Augustin M, et al. German S3-Guideline on the treatment of psoriasis vulgaris, adapted from EuroGuiDerm - Part 2: Treatment monitoring and specific clinical or comorbid situations. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2021;19(7):1092–1115.

- Salim A, Tan E, Ilchyshyn A, et al. Folic acid supplementation during treatment of psoriasis with methotrexate: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Br J Dermatol. 2006;154(6):1169–1174.

- van Ede AE, Laan RF, Rood MJ, et al. Effect of folic or folinic acid supplementation on the toxicity and efficacy of methotrexate in rheumatoid arthritis: a forty-eight week, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44(7):1515–1524.

- Ortiz Z, Shea B, Suarez Almazor M, et al. Folic acid and folinic acid for reducing side effects in patients receiving methotrexate for rheumatoid arthritis. Cochrane Database System Rev. 2002;:Cd000951.

- van Huizen AM, Menting SP, Gyulai R, SPIN MTX Consensus Survey Study Group, et al. International eDelphi study to reach consensus on the methotrexate dosing regimen in patients with psoriasis. JAMA Dermatol. 2022;158(5):561.

- van Huizen AM, Vermeulen FM, Bik C, et al. On which evidence can we rely when prescribing off-label methotrexate in dermatological practice? - a systematic review with GRADE approach. The Journal of Dermatol Treat. 2022;33(4):1947–1966.

- Verduijn MM, van den Bemt BJ, Dijkmans BA, et al. Correct use of methotrexate. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2009;153:A696.