Abstract

Background/Purpose

Amidst the emergence of new therapeutic options, traditional therapeutic plasmapheresis (TPE) used in diseases involving a toxic substance in the plasma, remains a viable alternative for cases of recalcitrant solar urticaria (SU). We emphasize the importance of documenting successful experience with repeated plasmapheresis to increase awareness amongst physicians and dermatologists regarding this effective treatment option.

Material and Method

We reported a case of recalcitrant SU that had not responded to a combination of H1-antihistamines, immunosuppressants, omalizumab and intravenous immunoglobulin. We introduced serial TPE, which involved two consecutive days of procedures for each course was introduced. We detailed the regimen and highlighted the clinical and objective benefits observed with multiple treatments. Additionally, we compared this to other plasmapheresis regimens and their treatment responses previously reported for solar urticaria.

Results

Our patient underwent serial TPE, totaling 42 procedures over five years. Following the last TPE session, phototesting showed a sustained prolongation of minimal urticating doses (MUDS), which exceeded the maximum tested doses across nearly all ultraviolet (UV) and visible light ranges, with the exception of the two short ultraviolet B (UVB) wavelengths. MUDs increased to 25 from 6 mj/cm2 at 307.5± 5nm, and to 500 from 15 mj/cm2 at 320 ± 10nm, before the initial TPE. In our review, we included five articles covering eight SU patients who received TPE. Of these, the five patients with positive intradermal tests responded particularly well immediately after treatment. However, the condition relapsed within two weeks in one patient and within two months in another. In contrast, the other three patients with negative intradermal tests, showed no significant benefits from the treatment. No serious side effects from TPE were reported amongst the patients.

Conclusions

This review underscores the efficacy of serial plasmapheresis procedures in treating refractory cases of SU, highlighting the robust results observed.

Introduction

Solar urticaria (SU) is a rare photodermatosis that can be extremely disabling. The pathogenesis is likely to be multifactorial (Citation1). This involves the complexity of the interactions between solar electromagnetic radiation, cutaneous microenvironment and skin chromophores (Citation2) binding of specific IgE crosslinking to mast cells in the skin causing FcεRI complex activation (Citation3) and mast cell degranulation. Early infiltration and degranulation of neutrophils, alongside several key innate immune pathways, have been recently identified in a detailed time course. Many of these prominent upstream regulators observed in SU exhibit similarities to those in chronic spontaneous urticaria (CSU) (Citation3). This leads to release various bioactive molecules, including histamine. Circulating autoantibodies that activate mast cells has been also reported (Citation4).

Treatment of SU is challenging. Many recalcitrant cases have been reported worldwide. For those who do not respond to high-dose H1 non-sedating antihistamines, there have been reports of successful treatment with systemic immunosuppressants, including methotrexate, cyclosporine, chloroquine, monoclonal IgE anti-body (Citation5,Citation6), intravenous immunoglobulin, phototherapy (Citation7) and plasmapheresis (Citation8). We report the initial case of refractory SU successfully treated with serial plasmapheresis, totaling 42 procedures over five years, with a long-term follow-up outcome.

Materials and methods

We present a 56-year-old lady was referred to our photobiology clinic in 2007 with a long-standing history of suspected photosensitivity. She reported the development of marked confluent erythema and swelling on her face and the other sun exposed areas within a few minutes of sun exposure, with resolution within 1 h. She never had systemic symptoms including angioedema.

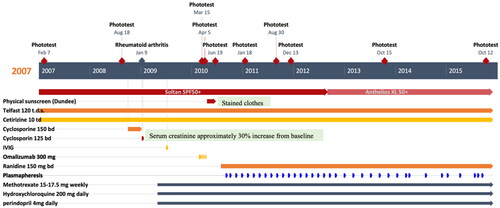

The clinical diagnosis was SU. Fexofenadine (Telfast®)120mg three times a day and cetirizine 10 mg three times a day had been commenced since her first visit by a primary physician. Rheumatoid arthritis was diagnosed in Febuary 2009. She had been also treated with methotrexate 15–17.5 mg weekly, hydroxychloroquine 250 mg daily and perindopril 4 mg daily since May 2009. She could not have ultraviolet B (UVB) desensitization as another combined treatment due to unavailability of the facilities at her local hospital.

Diagnostic assessment

Phototesting was undertaken one week following the discontinuation of the antihistamines. A monochromator, Mk II Ninewells Phototherapy (PHTH) Monochromatic light source (Bentham®) was used. The patient’s unaffected lower back skin was exposed to the following wavebands: 300 ± 5 nm, 307.5 ± 5 nm, 320 ± 10 nm, 340 ± 20 nm, 360 ± 20 nm, 380 ± 20 nm and 400 ± 20 nm. Responses were positive within 1 h with erythema, wheal, and flare reactions at all ranges of ultraviolet (UV) wavebands with minimal urticating doses (MUD) (). Lupus serology (Antinuclear, anti-Ro and La antibodies) was negative. Plasma spectrofluorimetry was negative for porphyrins. SU with an action spectrum through the UVB and ultraviolet A (UVA) wavebands was diagnosed in 2007.

Table 1. A long-term follow-up of minimal urticating dose (mj/cm2) by phototesting with a monochromator, Mk II Ninewells Phototherapy (PHTH) monochromatic light source (Bentham®).

Therapeutic intervention

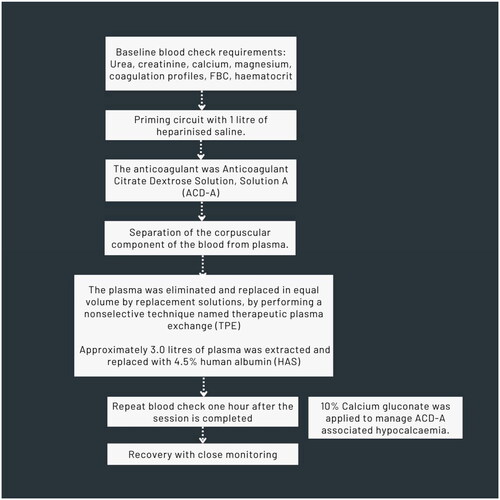

She had been advised to continue the combination of antihistamines and additional broad-spectrum sunscreen and physical sun protection. She had not noticed improvement with the treatments given. She still consistently developed the eruption within 5 min of sun exposure despite the sunlight around September time in the UK. She also failed to benefit from the combination of antihistamines and ciclosporine (). Single dose of Intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) (July 2009) and omalizumab 300 mg bi-weekly for four doses (February–April 2010) were also administered. She still had at least one episode per week within 5 min of sun exposure. She felt her daily lifestyle restricted particularly when she was on her holidays abroad in tropical countries. Physical sunscreen was also introduced as well as ranitidine 300 mg daily (July 2010). She had also been given an adrenaline auto-injector (EpiPen®) in order that she could travel on her holidays to hot countries including Africa, in case, she had a severe reaction. In June 2010, plasmapheresis was considered as an additional treatment. Therapeutic plasmapheresis (TPE) was introduced along with the combination of antihistamines, broad-spectrum sunscreen, methotrexate, and hydroxychloroquine (September 2010) (). The treatment regimen initially involved two consecutive days of procedures, followed by two similar procedures occurring in two weeks apart. During each procedure, approximately 3000 ml of plasma were extracted and replaced with 4.5% human albumin (HAS). Essential screening blood tests were conducted both before and after each procedure (). Subsequently, she underwent a set of two procedures every six weeks for three years (October 2013). The frequency of the procedure was then adjusted to every nine weeks for an additional two years (September 2015). The only observed side effect after treatment was hypocalcemia associated with anticoagulant citrate dextrose, solution A (ACD-A), for which 10% calcium gluconate was administered. TPE was otherwise generally well-tolerated.

Follow-up and outcomes ()

At six-month review after TPE six-weekly, she reported benefits with increased duration of light exposure required for symptoms provocation which corresponded to significant increase of MUDS across all UV wavebands, undertaken on 30 August 2011 ().

After 10 months of two-day TPE procedures, from September to November 2011, the patient reported that the provocation time for her condition had increased from 5 to 20 min, which resulted in improvement in her quality of life. After 18 months of plasmapheresis six-weekly, the patient reported stable condition of photosensitivity. Her maximum daytime exposure still was 20 min. At 28 months, the patient’s condition was still stable. Her MUDS on 15 October 2013 was stable and continued to improve. The interval of TPE treatment was reduced to once every nine weeks due to improvement of the patient’s condition. She was now affected by photosensitivity only when she traveled abroad. After two years of TPE every nine weeks, the patient could still tolerate up to 20 min of sun exposure before getting the eruption. This treatment also significantly liberated the patient in term of the patient’s activities of daily living particularly in the UK. The phototest on 12 October 2015 (Supplementary Figure 1) following her last therapeutic plasmapheresis (TPE) session (September 2015), revealed a persistent prolongation of MUDS, exceeding the maximum tested doses across all the UV and visible light ranges except two short UVB wavelengths. MUDs were 25 from 6 mj/cm2 before the first TPE at 307.5 ± 5 nm and 500 from 15 mj/cm2 at 320 ± 10 nm. She managed a holiday to a tropical country without significant problems with photosensitivity. Her sun tolerance had increased from immediate to 15 min of direct strong sunlight. She had been lost to a follow-up since the last phototest reading visit in October 2015.

Discussion

SU is a rare photodermatosis. It accounts for between 0.08% (Citation9) to 0.4% (Citation10) of all urticarias and 0.7% to 1.6% (Citation11) of photodermatoses. The classical presenting skin eruptions are wheals marked by erythematous raised plaques and itching, burning sensation (Citation12) and limited to sun-exposed areas. SU is reported to occur concomitantly with other types of physical urticarias (Citation13) and be aggravated by clothes (Citation14,Citation15). The urticarial response usually develops within 5 to 10 min after exposure to a corresponding eliciting wavelength, predominantly in UVA and visible light range (Citation16) and resolves within 24 h. Some patients can present with systemic symptoms including headache, nausea, dizziness, wheezing, syncope (Citation17) and rarely anaphylaxis. Treatment of SU is challenging. Many recalcitrant cases have been reported worldwide. For those who do not respond to high-dose H1 non-sedating antihistamines, there have been reports of successful treatment with systemic immunosuppressants, including methotrexate, cyclosporine, chloroquine, monoclonal IgE anti-body (Citation5,Citation6), intravenous immunoglobulin and plasmapheresis. Phototherapy is also reported as a treatment with variable efficacy (Citation2,Citation7). As circulating chromophores and autoantibodies have been identified in certain cases of SU (Citation18–20) and chronic spontaneous urticaria patients (Citation4), TPE serves as a strategy to eliminate large-molecular-weight substances and albumin-bound toxins including pathologic factors, circulating chromophores and autoantibodies in this case, whilst replacing them with a large volume of isotonic fluid solution. In addition to the removal of the pathologic factors which is the primary focus of its mechanism of action, TPE may also contribute beneficial effects in SU through increase in susceptibility of the antibody-producing cells to immunosuppressants and alteration in the immune system (Citation21). The first successful plasma exchange (Citation22) was reported in one SU patient with positive intradermal testing for circulating photoproduct. In that patient the treatment increased six folds the MUD to UVA and doubled it to visible light, resulting in one year without symptoms after the treatment. The summary of the outcome of TPE therapy in eight SU patients (Citation8,Citation22–27) reported was demonstrated in . Five (Citation8,Citation23,Citation25,Citation26) of them with positive intradermal test seemed to tolerate very well particularly immediately after the treatment. One (Citation26) of the five patients failed to response to the first treatment. TPE increased from 5 to more than 31 times as much as the pretreatment MUDs at UVA range; increased from 10 to 120 times as much as the pretreatment MUD at visible light range; increased around three times as much as the pretreatment MUD at UVB range. However, the condition was reported to relapse after TPE in two weeks in one (Citation26) and two months in another patient (Citation25). Combining TPE to UVA or psoralen ultraviolet light A (PUVA) therapy prolongs remission period (Citation8) and increase tolerance of sun exposure in patients sensitive to UVA (Citation8) and UVB (Citation8,Citation25). The relapse of symptoms is attributed to the temporary reduction of target substance levels achieved through TPE (Citation3). Conducting multiple procedures and maintaining systemic immunosuppressants, as seen in the previous case reported using UV phototherapy, are crucial to minimize antibody production following further sun exposure. By contrast, two of the SU patients treated with TPE had negative intradermal tests. Both of them appeared to have no significant benefits from the treatment. None of the patients received TPE had serious side effects reported. Our case had been suffering from severe and recalcitrant SU with broad eliciting wavebands from UVB to visible light confirmed by monochromator phototesting. She failed to sufficiently respond to the combination of antihistamines and ciclosporine (), nor to a single dose of IVIG and a total of four doses of omalizumab (300 mg every two weeks) (Supplementary Figure 2). Omalizumab provides a rapid effect as early as week 1 (Citation28,Citation29) and is effective in patients with low baseline serum IgE levels, in both CSU (Citation30) and chronic inducible urticaria (CIdU) (Citation29). Whilst the majority of patients with CIdU, approximately 75% achieved an optimal response (UAS 1–6) or complete remission, at four months, after completing four doses of omalizumab (300 mg every four weeks), approximately 10% of CIdU patients benefited from a fifth dose of omalizumab to achieve an optimal response (UAS 1–6) or complete remission at five months (Citation31). Increased exposure to the drug (Citation32), including higher doses, longer treatment durations and re-administrations after the first long-term cycle (Citation31), may be necessary in certain patients with chronic inducible urticaria (CIdU). We did not conduct baseline serum total IgE testing. It is possible that our patient may have benefited from a longer treatment duration of omalizumab.

Table 2. Literature review of the detailed procedures of plasmapheresis for solar urticaria.

Furthermore, she had not had intradermal testing done before TPE. We monitored our patient’s response by phototesting for MUDs (). She had subjectively noticed greater tolerance toward sun exposure in the UK since TPE was introduced. There was a slight change of MUDs one month after the fifth course of TPE. Since significant improvement of MUDs observed from immediately up to one week (Citation8) following TPE, this transient beneficial effect declines considerably at two weeks (Citation26) unless there is another systemic immunosuppressant as a treatment combination (Citation25). The negligible improvement of MUDs across UV wavebands was observed one month following the last TPE in our patient can be attributed to this. Unlike correcting symptoms of hyperviscosity in patients with WaldenstrÖm macroglobulinaemia, where TPE could provide an immediate result, the cumulative effect of multiple procedures enhances the efficacy of TPE to potentially achieve maximum outcome (Citation33–35). Considerable improvement of MUDs six weeks after the ninth course when compared to the baseline MUDs was subsequently demonstrated, eight to 16 times greater than baseline to UVB range and four to eight times greater than baseline to UVA range.

Interestingly, MUDs continued to gradually increase following consecutive treatments at both UV ranges during the eighth year following disease onset. The patient had her final phototest visit with us (Supplementary Figure 1) 12 days after the last TPE sessions, totaling 42 sessions. The result revealed a persistent prolongation of MUDs, which generally exceeded the maximum tested doses across all the UV and visible light ranges except two short UVB wavelengths. Specifically, MUDs were observed to be 4 times higher at 307.5 ± 5 nm and 33 times higher at 320 ± 10 nm compared to pre-TPE doses. Since approximately one-third of SU patients reported complete resolution in five years (Citation16) as well as 5 in 12 patients had temporal evolution in action spectrum and photosensitivity in seven years (Citation1), spontaneous resolution could not be ruled out in our case. Long-term serial TPE is an effective and safe treatment option for patients with SU which does not respond to any other treatments. However, successful implementation of therapeutic plasmapheresis requires highly specialized facilities, which are considered complex and costly. The clinical feasibility of this procedure in many medical care providers is subject to debate.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (313.1 KB)Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr B. Oberai (St David’s Health Centre, Middlesex, TW19 7HT) for referring the patient for investigations and specialist care; Dr Ying Xin Teo (Department of Dermatology, Southampton General Hospital, University Hospitals Southampton NHS Foundation Trust, SO16 6YD) for supportive information; Dr SL Walker and Mrs H. Naik (Photodermatology Unit, St John’s Institute of Dermatology, Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust, London, SE1 9RT, UK) for their technical expertise performing phototesting.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

References

- McSweeney SM, Sarkany R, Fassihi H, et al. Pathogenesis of solar urticaria: classic perspectives and emerging concepts. Exp Dermatol. 2022;31(4):1–7. doi: 10.1111/exd.14493.

- Schwarz T. UVA rush hardening - a new therapy of solar urticaria [German]. Aktuelle Derm. 2004;30(3):55–58.

- Rutter KJ, Peake M, Hawkshaw NJ, et al. Solar urticaria involves rapid mast cell STAT3 activation and neutrophil recruitment, with FcεR1 as an upstream regulator. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2024;153(5):1369–1380.e15. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2023.12.021.

- Aleksandraviciute L, Malinauskiene L, Cerniauskas K, et al. Plasmapheresis: is it a potential alternative treatment for chronic urticaria? Open Med. 2022;17(1):113–118. doi: 10.1515/med-2021-0399.

- Morgado-Carrasco D, Giácaman-Von der Weth M, Fustá-Novell X, et al. Clinical response and long-term follow-up of 20 patients with refractory solar urticaria under treatment with omalizumab. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;88(5):1110–1111. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2019.05.070.

- Hershkovitz Y, Khanimov I, Rubin L, et al. Successful ligelizumab treatment of severe refractory solar urticaria. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2023;11(8):2576–2577. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2023.01.052.

- Lyons AB, Peacock A, Zubair R, et al. Successful treatment of solar urticaria with UVA1 hardening in three patients. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2019;35(3):193–195. doi: 10.1111/phpp.12447.

- Hudson-Peacock MJ, Farr PM, Diffey BL, et al. Combined treatment of solar urticaria with plasmapheresis and PUVA. Br J Dermatol. 1993;128(4):440–442. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1993.tb00206.x.

- Chong WS, Khoo SW. Solar urticaria in Singapore: an uncommon photodermatosis seen in a tertiary dermatology center over a 10-year period. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2004;20(2):101–104. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0781.2004.00083.x.

- Champion RH. Urticaria: then and now. Br J Dermatol. 1988;119(4):427–436. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1988.tb03246.x.

- Nakamura M, Henderson M, Jacobsen G, et al. Comparison of photodermatoses in African-Americans and Caucasians: a follow-up study. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2014;30(5):231–236. doi: 10.1111/phpp.12079.

- Pesqué D, Ciudad A, Andrades E, et al. Solar urticaria: an ambispective study in a long-term follow-up cohort with emphasis on therapeutic predictors and outcomes. Acta Derm Venereol. 2024;104:adv25576. doi: 10.2340/actadv.v104.25576.

- Diehl KL, Erickson C, Calame A, et al. A woman with solar urticaria and heat urticaria: a unique presentation of an individual with multiple physical urticarias. Cureus. 2021;13(8):e16950. doi: 10.7759/cureus.16950.

- Gardeazabal J, González-Pérez R, Bilbao I, et al. Solar urticaria enhanced through clothing. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 1998;14(5-6):164–166. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0781.1998.tb00036.x.

- de Gálvez MV, Aguilera J, Navarrete-de Gálvez E, et al. An unusual case of solar urticaria exacerbated by clothing: confirmation through phototesting. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2023;39(4):403–406. doi: 10.1111/phpp.12845.

- McSweeney SM, Kloczko E, Chadha M, et al. Systematic review of the clinical characteristics and natural history of solar urticaria. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;89(1):138–140. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2023.01.039.

- Ramsay CA. Solar urticaria. Int J Dermatol. 1980;19(5):233–236. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1980.tb00314.x.

- Horio T, Minami K. Solar uticaria. Photoallergen in a patient’s serum. Arch Dermatol. 1977;113(2):157–160. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1977.01640020029003.

- Horio T. Photoallergic urticaria induced by visible light. Arch Dermatol. 1978;114(12):1761–1764. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1978.01640240003001.

- Kojima M, Horiko T, Nakamura Y, et al. Solar urticaria. Arch Dermatol. 1986;122(5):550–555. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1986.01660170080024.

- Reeves HM, Winters JL. The mechanisms of action of plasma exchange. Br J Haematol. 2014;164(3):342–351. doi: 10.1111/bjh.12629.

- Duschet P, Leyen P, Schwarz T, et al. Solar urticaria: treatment by plasmapheresis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1986;15(4 Pt 1):712–713. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(86)80103-7.

- Duschet P, Leyen P, Schwarz T, et al. Solar urticaria–effective treatment by plasmapheresis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1987;12(3):185–188. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.1987.tb01891.x.

- Leenutaphong V, Hölzle E, Plewig G, et al. Plasmapheresis in solar urticaria. Photodermatol. 1987;4(6):308–309.

- Leenutaphong V, Hölzle E, Plewig G, et al. Plasmapheresis in solar urticaria. Dermatologica. 1991;182(1):35–38. doi: 10.1159/000247734.

- Collins P, Ahamat R, Green C, et al. Plasma exchange therapy for solar urticaria. Br J Dermatol. 1996;134(6):1093–1097. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1996.d01-908.x.

- Bissonnette R, Buskard N, McLean DI, et al. Treatment of refractory solar urticaria with plasma exchange. J Cutan Med Surg. 1999;3(5):236–238. doi: 10.1177/120347549900300503.

- Saini S, Rosen KE, Hsieh H-J, et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled, dose-ranging study of single-dose omalizumab in patients with H1-antihistamine-refractory chronic idiopathic urticaria. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128(3):567 e1–573 e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.06.010.

- Veleiro-Pérez B, Alba-Muñoz J, Pérez-Quintero O, et al. Delayed pressure urticaria: clinical and diagnostic features and response to omalizumab. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2022;183(10):1089–1094. doi: 10.1159/000524887.

- Kaplan AP, Joseph K, Maykut RJ, et al. Treatment of chronic autoimmune urticaria with omalizumab. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;122(3):569–573. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.07.006.

- Damiani G, Diani M, Conic RRZ, et al. Omalizumab in chronic urticaria: an Italian survey. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2019;178(1):45–49. doi: 10.1159/000492532.

- Maurer M, Metz M, Brehler R, et al. Omalizumab treatment in patients with chronic inducible urticaria: a systematic review of published evidence. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018;141(2):638–649. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2017.06.032.

- Pineda AA. Selective therapeutic extraction of plasma constituents, revisited. Transfusion. 1999;39(7):671–673. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1999.39070671.x.

- Derksen RH, Schuurman HJ, Meyling FH, et al. The efficacy of plasma exchange in the removal of plasma components. J Lab Clin Med. 1984;104(3):346–354.

- Derksen RH, Schuurman HJ, Gmelig Meyling FH, et al. Rebound and overshoot after plasma exchange in humans. J Lab Clin Med. 1984;104(1):35–43.