Abstract

Purpose

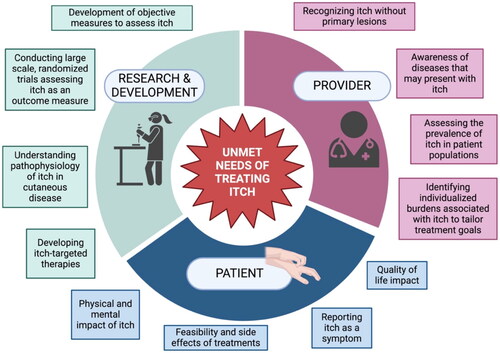

Pruritus is an unpleasant sensation that creates the urge to scratch. In many chronic conditions, relentless pruritus and scratching perpetuates a vicious itch-scratch cycle. Uncontrolled itch can detrimentally affect quality of life and may lead to sleep disturbance, impaired concentration, financial burden, and psychological suffering. Recent strides have been made to develop guidelines and investigate new therapies to treat some of the most common severely pruritic conditions, however, a large group of diseases remains underrecognized and undertreated. The purpose of this article is to provide a comprehensive review of the challenges hindering the treatment of pruritus.

Methods

An online search was performed using PubMed, Web of Science, Google Scholar, and ClinicalTrials.gov from 1994 to 2024. Included studies were summarized and assessed for quality and relevance in treating pruritus.

Results

Several barriers to treating pruritus emerged, including variable presentation, objective measurement of itch, and identifying therapeutic targets. Itch associated with autoimmune conditions, connective tissue diseases, genodermatoses, cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, and pruritus of unknown origin were among the etiologies with the greatest unmet needs.

Conclusion

Treating pruritus poses many challenges and there are many itchy conditions that have no yet been addressed. There is an urgent need for large-scale controlled studies to investigate potential targets for these conditions and novel therapies.

1. Introduction

Itch is the most common complaint associated with skin conditions, which are the fourth leading cause of nonfatal disease burden (Citation1). Pruritus is a driving factor for seeking treatment, with more than one-third of individuals visiting a dermatological practice endorsing pruritus and nearly 20% of the general population suffering chronically from itch that lasts longer than 6 weeks (Citation2).

While new therapies are continuously emerging for pruritus, there remains a great unmet need for providing symptom relief. Certain common dermatoses, such as atopic dermatitis (AD), have been comprehensively reviewed for gaps in treatment (Citation3–5). Further, more than 20 novel targeted therapies have been investigated for type 2 chronic inflammatory diseases, many of which present primarily with pruritus (Citation6). However, there are numerous other diseases associated with debilitating pruritus that lack adequate treatments and awareness. In this review, we explore the landscape of unmet needs associated with treating pruritus. Through this lens, we illuminate many of the underrecognized pruritic conditions stemming from autoimmune, genetic, and cancerous processes, as well as those affecting special populations.

2. General challenges to treating itch

2.1. Early diagnosis and variable clinical presentation

Pruritus has an extensive range of potential etiologies and variable clinical presentation, which can make diagnosis challenging. Many providers may not be aware of the signs and symptoms of the rarer etiologies of pruritus, especially if primary lesions are absent (Citation7). This can lead to extensive periods of work-up and delayed diagnoses or even misdiagnoses due to the mimicking presentations (Citation7). In many chronic inflammatory conditions associated with pruritus, early diagnosis and control of the underlying processes are pivotal to preventing disease progression (Citation7).

The patient experience of itch is subjective and may depend on demographic factors such as gender, race, and ethnicity. For instance, women are more likely to seek medical care for itch that worsens with psychosomatic factors, neuropathic symptoms, and secondary lesions from scratching, whereas men reporting itch are more likely to have systemic comorbid conditions (Citation8,Citation9). Further, pruritic dermatoses are not uniform across racial and ethnic groups. African American patients have a higher likelihood of experiencing a greater severity of itch secondary to AD, Prurigo Nodularis (PN), and primary biliary cholangitis than Caucasian patients (Citation10). African American patients are also at increased risk of having systemic disorders associated with itch, such as end-stage renal disease and HIV-related pruritus (Citation11). Increasing awareness of the differing presentations of chronic pruritic skin conditions across all specialties, including internal medicine, primary care, rheumatology, neurology, and genetics, is an important step in early diagnosis.

2.2. Identifying therapeutic targets

Research over the last two decades has yielded an abundance of information regarding the pathogenic drivers of itch. Numerous specific cytokines, including interleukin (IL)-4, IL-13, and IL-31 have been implicated in the type 2 inflammatory process associated with pruritus, along with mast cells, eosinophils, neuropeptides, and janus kinases (JAKs) (Citation6). Targeted drugs have been developed for several pruritic conditions, such as the anti-IL-4/IL-13 monoclonal antibody, dupilumab, which is approved for AD and prurigo nodularis (PN). Nemolizumab is an IL-31 inhibitor that recently demonstrated efficacy in reducing the itch associated with AD and PN in phase III trials and will likely be approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (Citation12). JAK inhibitors have also proven to be key players in controlling pruritus (Citation13). Ruxolitinib 1.5% cream is a JAK 1/2 inhibitor that was the first-in-class drug to be approved by the FDA for the treatment of AD. Moreover, abrocitinib and upadacitinib, selective inhibitors against JAK1, have been approved for the treatment of moderate to severe atopic dermatitis. While many advances have been made toward targeting some of the most common immune-mediated pruritic conditions, there remains an abundance of conditions with poorly understood pathophysiology.

As such, broad-spectrum immunosuppressants, such as systemic corticosteroids, cyclosporine, methotrexate, and azathioprine are often used as a default treatment option for those conditions thought to have an immune component (Citation7). While this approach may be effective, these agents primarily function via widespread prevention of T-cell activation or proliferation and may be associated with poor safety profiles (Citation14). Newer immunomodulators that target specific points in the pruritic pathway have shown promise in alleviating pruritus with fewer adverse effects (Citation14). Unfortunately, drug development for many pruritic conditions has been hindered by the lack of available information on the distinct immune components at play. Thus, the identification of predictive biomarkers is at the forefront of medical needs (Citation7).

2.3. Objectively measuring itch

A challenge in investigating antipruritic agents is adequately capturing the patient experience of pruritus. While the development of the visual analog scale (VAS) and itch numeric rating scale (NRS) was a breakthrough in objectively measuring pruritus in clinical trials, they are unidimensional and do not fully encompass the itch characteristics (Citation15). Such information could be extremely helpful in evaluating the efficacy of treatments for specific causes of pruritus. There is thus a need for the development of additional tools to translate subjective itch into a more robust primary endpoint in clinical trials.

We will not be able to cover all itchy disease states as that is beyond the scope of this review, however, we will describe some of the most pressing conditions with unmet needs for treating itch.

3. Chronic pruritus of unknown origin (CPUO)

Chronic pruritus of unknown origin defines a prolonged period of pruritus without a single identifiable cause. As CPUO is a diagnosis of exclusion, patients often undergo extensive testing and work-up to rule out potential etiologies. This process can lead to years of suffering without answers (Citation16). CPUO is highly underrecognized and underdiagnosed.

While it is not possible to select a singular cause of CPUO, there may be clues that point toward a particular contributing system. Taking a thorough clinical history and physical exam with special attention to the distribution and characteristics of lesions, if present, can help identify a direction for treatment. These may include primary dermatoses, systemic, neuropathic, or psychogenic causes, or a mix (Citation17). Emerging biomarkers may also serve as predictors of disease. Select cells of the type 2 immune system, for instance, have also been identified as potential causative candidates of pruritus, including memory-type T-helper 2 (Th2) cells, mast cells, and basophils (Citation18,Citation19). These cells are thought to interact with neuronal circuits throughout the periphery, creating neuroimmune axes that contribute to itch sensations (Citation19,Citation20). B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP), is an itch-selective neuropeptide that is strongly correlated with itch severity in patients with CPUO and should be included in the diagnostic workup (Citation21). Implementing this information in the training of dermatologists, primary care providers, and even physicians from specialties commonly seeing itch in their patients, such as neurology, nephrology, hepatology, and psychiatry, will help meet the unmet need of increasing education and awareness of CPUO.

One of the biggest hurdles to approaching CPUO is that there is no FDA-approved treatment and no true therapeutic guidelines (Citation22). As such, many providers struggle to select a treatment that will achieve relief, especially in refractory cases. Fortunately, there is an abundance of treatment options available for treating CPUO with additional studies and clinical trials underway, although there is an unmet need for a unified path to selecting an agent. Of note, abrocitinib, a selective JAK1 inhibitor approved for the treatment of AD, recently completed phase II testing with the majority of CPUO patients achieving itch relief within 12 weeks (Citation23). Although abrocitinib is one of only a few agents to undergo testing in randomized controlled trials (RCTs) for CPUO to date, it demonstrates the potential for the expanded use of drugs on the market. Furthermore, a major phase III trial is currently underway to evaluate the efficacy and safety of dupilumab in adults with CPUO aged 18–90 (NCT05263206). The results of this study are highly anticipated and may provide evidence to support establishing a standardized treatment option for CPUO. The wide age range of individuals included in this ongoing trial is of utmost importance for addressing CPUO specifically in the elderly population.

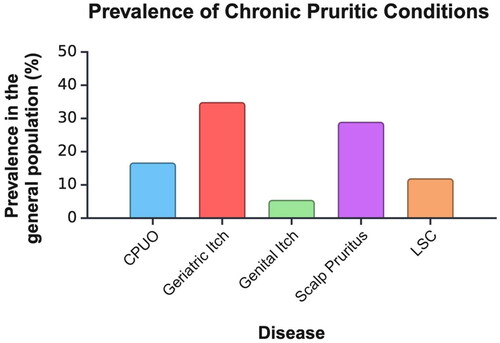

4. Pruritus in the elderly

Geriatric itch is defined as chronic itch in individuals over the age of 65. It is the most common skin disorder in the elderly, with studies reporting a prevalence ranging from 11–68% () (Citation24–26). Further, the prevalence of itch has been shown to increase with age within this population as assessed in both the inpatient and outpatient settings. A study analyzing over 4000 geriatric patients who had been admitted to a single hospital reported chronic pruritus in 12% of patients over the age of 65 and nearly 20% of patients over the age of 85 (Citation26). A subsequent cross-sectional study of 2076 adults found that a striking 46% of patients over the age of 80 in a primary care setting suffered from chronic pruritus, illustrating a significant unmet need for adequate treatment (Citation27).

Figure 1. The overall prevalence of conditions presenting with chronic pruritus in the general population. Prevalence data has been extracted from epidemiological studies referenced in this article.

CPUO: chronic pruritus of unknown origin, LSC: lichen simplex chronicus

Chronic pruritus in the elderly population may be partially attributed to physiologic changes in the skin structure (Citation28). Over time, the skin loses its ability to regenerate, and environmental effects provoke decreased barrier function and skin hydration (Citation29). While the vast majority of geriatric itch has an unknown cause, it is important to be aware of certain diagnosable pathologic changes. For instance, the presence of intraepidermal acantholysis on histology and a pruritic papulovesicular eruption on the trunk of a white male may represent transient acantholytic dermatosis, or Grover’s disease (Citation30). Grover’s disease has been diagnosed in 0.1–0.8% of the population and can be extraordinarily itchy (Citation31). While it is not limited to the elderly population, it is most common in men around the age of 60 years or later. Although rare and often self-limited, Grover’s disease may be associated with malignancy or cancer therapy and should be distinguished from CPUO (Citation32).

Managing chronic pruritus in the elderly population comes with unique challenges, including co-morbid conditions, long medication lists, diminished cognitive function, and physical limitations (Citation33). Upon devising an initial treatment plan, it is important for providers to consider quality of life and treatment goals (Citation34). When presenting with several systemic and perhaps severe conditions, a patient’s complaint of pruritus may seem obsolete. Yet, pruritus in the elderly population can lead to clinical depression and sleep impairment, which not only affects morbidity but has also been shown to increase mortality by up to 17% in certain patient populations (Citation35). It is thus imperative for both patients and their providers to prioritize the implications of this symptom. The current hallmark of treating chronic pruritus in elderly patients is topical therapy (Citation33). Systemic medications may also be prescribed with increased caution (Citation33). Several novel drugs and approved medications with new indications are under investigation and have the potential to dramatically improve the quality of life in older adults. () However, clinicians face the fear of adding powerful drugs to a perhaps already lengthy medication list. A patient’s age should be a factor, but not the sole deterrent in selecting a systemic agent. With sufficient supporting evidence and a shared decision-making process, such treatments should be highly considered in refractory cases and when not contraindicated. Aside from systemic therapy, a holistic approach may also help improve the treatment of geriatric itch. Psychological interventions such as habit reversal, relaxation, and cognitive behavioral therapy may help reduce stress and dysfunctional illness perceptions (Citation34,Citation36).

Table 1. Summary of treatments approved by the FDA and current trials under investigation for the treatment of itch in various diseases.

5. Localized pruritus

5.1. Scalp pruritus

The skin on the scalp is unique in that it contains densely innervated hair follicles and dermal vasculature (Citation37). While it is commonly associated with physical findings such as scaling, flaking, or erythema, such as in psoriasis and seborrheic dermatitis, it can also appear without any skin lesions (Citation37). There are several barriers to treating an itchy scalp. Like other chronic pruritic conditions discussed above, epidemiological studies of prevalence in the general population are greatly lacking. To date, the prevalence of scalp pruritus in various populations has been described between 13–45% (Citation38). Another unmet need for treating this condition is understanding the pathophysiology, which may be prurioreceptive, neuropathic, neurogenic, or psychogenic (Citation38). An associated disease may not be identifiable after conducting a thorough history and physical exam, in which case a diagnosis of scalp pruritus of undetermined origin is appropriate (Citation38). These patients are often told that they have a sensitive scalp, leaving them with no answers and no treatment (Citation38). Sensitive skin is a syndrome defined by the occurrence of unpleasant sensations (stinging, burning, pain, pruritus, and tingling) in response to stimuli that normally should not provoke such sensations (Citation39). It has been reported that about one-third of the population suffers from a sensitive scalp, with increasing frequency as age advances (Citation40).

Unfortunately, management of scalp itch can be challenging due to its complex and multifactorial nature. General first-line approaches include topical therapy with anti-inflammatory properties and avoidance of chemical and physical irritants (Citation38). The inherent characteristics of the scalp also make it difficult to treat. For instance, the presence of hair and the thickness of the scalp may prevent adequate penetration of agents. Furthermore, ointments and creams are undesirable to many patients due to a greasy cosmetic appearance, leading to decreased compliance (Citation38). Accordingly, there is a need to develop treatment options for scalp pruritus that are easier to apply and prioritize patient preferences.

5.2. Ano-genital itch

Anal and genital itch greatly affects men and women and has a well-established link with worsened quality of life, especially regarding psychiatric comorbidities. Among hospitalized patients, those with genital pruritus have a higher inpatient burden with increased odds of admission for a psychiatric disorder as well as longer hospital stays (Citation41). Similarly, anal itch, also known as pruritus ani, has a significant influence on the level of depressive symptoms a patient experiences (Citation42). Itch involving the genital and anus is associated with an uncontrollable desire to scratch in an area deemed to be socially unacceptable, leading to embarrassment in public scenarios (Citation43).

Pruritus ani occurs in 1–5% of the adult population and is more common in males than females (Citation44). There are numerous potential causes of pruritus ani, ranging from dermatologic conditions such as perianal eczema, psoriasis, and hidradenitis suppurativa, to local irritants, candidal infections, drug-induced, and neuropathic causes (Citation45). Benign anorectal conditions like hemorrhoids and fissures are often the most common causes of anal itch, along with frequent diarrhea or loose stools (Citation46). However, malignancy must be considered given that colorectal cancer, Paget’s disease, and squamous cell carcinoma are all possible contributors to secondary anal pruritus (Citation47). Additionally, underlying neuropathic disease is highly likely (Citation48). In a study of 20 patients with anogenital pruritus, 80% were found to have lumbosacral radiculopathy (Citation49). Currently goals of treating pruritus ani focus on restoring the perianal skin to a clean, dry, and intact state (Citation50). Following additional preventive recommendations of irritant removal, and barrier creams, treatment options for pruritus involving the anus are generally limited to those providing temporary relief, such as topical calcineurin inhibitors or topical corticosteroids (TCS), and may have adverse effects if used long-term (Citation51,Citation52). Oral antihistamines may have some benefit in addressing nocturnal pruritus, although this is likely a product of their sedating properties (Citation47). This illuminates the need for the development of feasible conservative treatments for patients and perhaps a focus on systemic therapy. A novel, lidocaine-based topical ointment recently demonstrated resolution of anal pruritus in 90% of patients during a two-week study (Citation50). Initially trialed over two decades ago, injections of methylene blue may be an effective approach for treating intractable idiopathic anal pruritus according to a recent systematic review and meta-analysis, however higher quality studies are necessary to confirm (Citation53). Gaba - ergic drugs are particularly helpful for those cases associated with lumbosacral neuropathy (Citation48). There may also be a role for repurposing of currently approved antipruritic drugs for pruritus ani, as cases have been reported of anal itch reduction with the use of dupilumab (Citation54).

Estimating the true prevalence of itch in the genitalia is challenging, as most epidemiological reports to date have focused on individual conditions involving genital itch as opposed to the sensation of itch itself. Further, reports of genital itch in women are much more robust than in men, revealing the need for additional large-scale studies to better characterize the magnitude of impact. Despite the lack of research on genital itch in males, there is evidence demonstrating a substantial clinical impact. In an international study of 354 patients with genital psoriasis, 87% reported itch, and male sex was a significantly predisposing characteristic for the development of genital involvement (Citation55).

According to the data available, vulvar pruritus affects 5–10% of women (Citation56,Citation57) This is likely an underrepresentation of vulvar itch, as many women feel uncomfortable discussing the topic with their physicians. Likewise, vulvar itch carries a component of social embarrassment associated with the urge to scratch in public and negative impacts on sexual functioning (Citation58). While vulvar pruritus may be caused by various inflammatory, infectious, and neoplastic processes, skin conditions affecting the genital area are usually responsible (Citation58,Citation59). As such, it is critical to expand the awareness of conditions affecting the vulva to primary care providers and gynecologists to improve timely diagnoses. Common causes include AD, contact dermatitis, seborrheic dermatitis (SD), lichen simplex chronicus, genital psoriasis, lichen planus (LP), and lichen sclerosus et atrophicus (LSA), which will be discussed in the following section (Citation59).

In general, there is very little evidence to support the specific management of genital itch. The hallmark of conservative therapy focuses on avoiding potential triggers, such as wearing silk underwear to diminish external irritation (Citation60). Expert committees have recommended potent to very potent TCS for persistent AD, SD, genital psoriasis, LP, and LSA based on level I/II evidence from experimental studies (Citation59,Citation61). Although it may be difficult to establish a primary or secondary cause of vulvar pruritus, both are managed similarly at first, so it is appropriate to initiate antipruritic therapy as soon as possible to avoid prolonged suffering (Citation58). In addition to recommending a treatment, patients must be informed how to correctly apply these agents, as the genital area is incredibly sensitive to TCS. A pea-sized amount should be sufficient to provide a thin layer of coverage while decreasing the risk of developing atrophy and striae (Citation59). The only other level I evidence supporting genital itch treatment is for the use of topical vitamin D analogues in genital psoriasis (Citation59). Other recommended treatments based on expert opinion or subjective clinical experience include topical antifungals and calcineurin inhibitors, although these may be associated with burning on application (Citation59). In general, ointments with high fat content are preferred to creams on the anogenital skin due to their lipid-replenishing properties and reduced need for preservatives, thus lowering the risk of contact allergy (Citation56,Citation61). On this premise, there is a gap in RCTs investigating treatments for genital itch that should be explored.

5.3. Notalgia paresthetica and Brachioradial pruritus

Notalgia paresthetica (NP) is a cutaneous neuropathy that presents with unilateral localized pruritus, predominantly in the interscapular region of the back (Citation62). Brachioradial pruritus (BRP) is a neuropathic pruritus over the dorsolateral aspects of arms and forearms (Citation63). Pathophysiology is thought to be a product of damaged or entrapped spinal nerves, typically at the T2–T6 and C4–C7 levels in NP and BRP respectively, due to spinal compression or degenerative changes (Citation48,Citation64,Citation65). The exact prevalence of both conditions is unknown, although NP seems to be more common than BRP (Citation62,Citation66).

Both conditions are resistant to several traditional antipruritic therapies, including antihistamines and topical glucocorticoids, and greatly impact the lives of suffering patients (Citation48,Citation67). Variable antipruritic benefit has been reported with lidocaine infusions, intradermal botulinum toxin, capsaicin patches, gabapentin, and amitriptyline, although no first-line choice has been established (Citation62). In the authors’ clinical experience, gabapentin and pregabalin seem to be the most effective for reducing itch in these conditions. However, these unpublished benefits are accompanied by adverse effects, especially in females, in whom weight gain is a common complaint. A recent cross-sectional interview study of 30 participants with NP found that >50% experienced severe to very severe itch for nearly 3 years, with 73% receiving no treatment at the time of the study (Citation68). Another study demonstrated that itch in 76 patients with BRP and NP had a significant impact on their quality of life with BRP having a greater association with QOL than NP (Citation69). This emphasizes the patient burden of the pruritus associated with these neuropathies and the unmet need for additional therapeutic options. Currently there are no FDA-approved therapies for NP or BRP. Breakthrough studies have begun to emerge for the treatment of NP, with great interest in the selective kappa opioid receptor agonist, difelikefalin. In a phase II trial, difelikefalin was found to reduce worst-itch intensity scores by 4.0 points compared to 2.4 points in placebo over 8 weeks (Citation67). However, adverse effects were prominent, causing 19% of patients in the intervention group to discontinue treatment (Citation67). Larger scale studies are ongoing.

5.4. Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus

LSA is a chronic inflammatory dermatosis that predominantly affects women and has a high preference for the vulvar and perianal regions, although it may occasionally be generalized (Citation70). LSA affects women up to ten times more often than men and peaks in two age groups: prepubertal girls (0.1%) and postmenopausal women (3%) (Citation71). This condition is notorious for presenting with intractable itch and white, polygonal papules that coalesce into thin, atrophic, white plaques or patches (Citation71). Notably, repeated scratching in LSA may lead to ecchymoses scarring, sensory abnormalities, and negative psychosexual impact (Citation72). Furthermore, genital LSA carries a risk of malignant transformation to squamous cell carcinoma in 2–6% of women, emphasizing the importance of early control and lifelong monitoring (Citation71,Citation73,Citation74).

LSA is frequently underdiagnosed. A content review of 527 public online forum entries posted by women with LSA revealed several common themes of concern, including that women attribute frequent misdiagnosis or delayed diagnosis to an overall lack of knowledge, experience significant frustrations and social justice issues, and rely on finding online communities to provide support (Citation75). LSA is also a diagnostic challenge in pediatric patients. An analysis of 38 children with LSA found a delay in diagnosing 80% of the study’s patients (Citation76).

Despite several published management guidelines, treatment options for LSA are limited, especially for ameliorating itch (Citation77). The gold standard treatment recommendation for adult patients with LSA is clobetasol propionate 0.05% or mometasone furoate 0.1% ointment for up to 3 months or intralesional glucocorticoids (Citation72). Several other topical and systemic options may be suggested as 2nd and 3rd-line options, with lower levels of supporting evidence. There is thus not only a great unmet need for disease-specific medication in LSA, but also increased knowledge, awareness, and support from healthcare providers.

5.5. Lichen simplex chronicus

Lichen simplex chronicus (LSC) is one of the most common forms of chronic localized pruritus affecting an estimated 12% of the general population (Citation78). LSC starts with an intractable itch that leads to thickening and scaling of the skin with repeated mechanical manipulation (Citation79). This secondary dermatitis often presents in symmetrical areas of the body that are easy to reach, namely the extremities, upper back, and genitalia (Citation79). Much like LSA, LSC impacts women with a greater frequency than men, although it is more prevalent between the ages of 30 and 50 as opposed to postmenopausal and prepubertal (Citation78). The knowledge of the pathophysiology underlying LSC has made significant advances in recent years, however, a large portion remains unclear and the etiology seems to be multifactorial. As such, treatments tend to be broad and aim to repair barrier function, reduce inflammation, and most importantly, interrupt the relentless itch-scratch cycle. Currently, there are no comprehensive evidence-based guidelines for therapy, and very few randomized controlled clinical trials have been conducted in this population (Citation80). One of the agents currently being investigated for antipruritic effect in LSC is KM-001, a topical inhibitor of transient receptor potential vanilloid-3 (TRPV3) (Citation81). TRPV3 is an ion channel that is highly expressed in keratinocytes and plays a key role in inflammation and chronic pruritus (Citation81). Results are highly anticipated and may help address the urgent unmet need for novel drugs to treat itch in LSC.

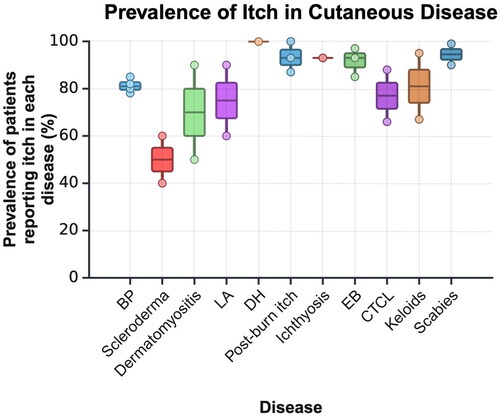

5.6. Lichen amyloidosis

Lichen amyloidosis (LA) is characterized by chronic pruritus and deposition of amyloid in the papillary dermis. It is thought that scratching is the precipitating factor for local inflammation and the transformation of apoptosed keratinocytes into amyloid deposits (Citation82). As such, LA may sometimes be considered a variant of LSC, given the parallel processes of primary itch and secondary dermatitis appearing as domed scaly hyperkeratotic papules largely on the shins (Citation83). Unlike the other the cutaneous lichenoid processes described above, LA affects males more than females and is more common in South America and Asia, where the prevalence is about 0.01% (Citation84). There is an unmet need for epidemiological studies in the general population and Caucasian individuals. Pruritus is a prominent and debilitating feature of LA and is present in 60–90% of patients (Citation85,Citation86). While the pathophysiology is not entirely clear, reduced nerve fiber density in the epidermis and dermo-epidermal junction may be responsible for the severe itch in LA via sensitizing and damaging existing fibers (Citation87). Additionally, pruritus is likely partially attributed to an association between hypersensitivity of cutaneous nerve fibers and increased IL-31 receptors (Citation86).

The treatment of pruritus in lichen amyloidosis is difficult, as many cases are refractory to conventional therapy or recur after a period of minimal relief. Given the emerging knowledge of key players in LA, there is a need for clinical trials investigating targeted therapies. Agents targeting the IL-31 receptor and its subunit, oncostatin-M receptor β, warrant further exploration (Citation88). Data from case series, case reports, and small uncontrolled studies note some success with therapies including phototherapy, laser therapy, methotrexate, and oral retinoids, however, their efficacy on itch has not been directly compared. Increasing the study of targeted therapy for LA may lead to the development of standard management guidelines, which do not currently exist.

6. Pruritic autoimmune conditions

6.1. Bullous pemphigoid

Bullous pemphigoid (BP) is the most common autoimmune subepidermal blistering skin disease. It presents more frequently in females and older patients, with tense blisters and itchy urticarial erythema primarily on the trunk and extremities (Citation7,Citation89). The incidence of BP has increased by 1.9–4.3-fold over the past two decades with an exponential rise in cases in patients older than 80 years old (Citation90). The severe itching associated with BP affects 85% of this disease population and has proven difficult to control () (Citation89,Citation91). Continued research on the pathophysiology underlying BP may help illuminate the key itch mediators at play. Currently, it has been clearly demonstrated that eosinophils, substance P, neurokinin 1 R, IL-31, IL-31 receptor A, oncostatin M receptor-ß (OSM-R ß), IL-13, periostin, and basophils are involved in BP-associated pruritus (Citation89). Circulating IgG antibodies against hemi-desmosomal proteins BP180 and BP230, as well as IgE autoantibodies, have been implicated in the pathogenesis of itch in BP (Citation92–95). Moreover, high-affinity IgE receptors are present on mast cells and eosinophils. When bound, proinflammatory cytokine release leads to the degradation of BP180 and ultimately, blister formation (Citation96).

Figure 2. The prevalence of itch in patients diagnosed with various genetic, autoimmune, and cancerous cutaneous diseases. The prevalence for each condition was extracted from epidemiological studies referenced in this review. Where multiple studies were available, all values were combined into boxes showing the 2nd and 3rd quartiles. The upper- and lowermost points on the vertical axis represent the minimum and maximum prevalences reported in each condition. Where only one epidemiological study was found, a horizontal line represents the prevalence instead of a box.

BP: bullous pemphigoid, LA: lichen amyloidosis, DH: dermatitis herpetiformis, EB: epidermolysis bullosa, CTCL: cutaneous t-cell lymphoma

A highly underrecognized challenge to treating BP is arriving at the correct diagnosis as early as possible. BP may appear as an atypical combination of pruritus and a prurigo-, urticaria-, or eczema-like presentation without blisters in up to 20% of cases, contributing to its misdiagnosis (Citation90,Citation97,Citation98). Notably, a systematic review of 132 cases found that the absence of frank bullae delayed diagnosis for nearly two years (Citation99). In current practice, many providers largely rely on clinical signs of bullae to consider BP. Recently, it has been recommended that the minimal criteria for diagnosing pemphigoid be expanded to include pruritus and/or cutaneous blisters, a biopsy demonstrating linear IgG and/or complement 3c deposits by direct immunofluorescence (IF), and/or positive epidermal side staining of IgG by indirect IF on salt-split skin substrate in a serum sample (Citation100). This would allow for the identification of both bullous and non-bullous variants. Despite advances in diagnostic recommendations, there remains a great unmet need for increasing awareness of the variable patterns of BP. Continuing education for both patients and providers, including those outside the field of dermatology, is warranted. A schematic highlighting the unmet needs of treating itch from various perspectives is shown in .

The mainstay of treatment for patients with BP is high-potency TCS, with the addition of systemic corticosteroids, immunosuppressants, plasma exchange, or intravenous immunoglobulins (IVIG) when appropriate (Citation101,Citation102). Oral tetracyclines were also found to be effective in the short-term control of blisters with fewer long-term safety concerns, although their impact on reducing pruritus was not specifically reported (Citation103). Treatment with steroids generally leads to pruritus remission in greater than 90% of patients, but their long-term use frequently causes serious adverse effects, especially in the elderly population (Citation104,Citation105). Furthermore, relapses are very common, and if initial treatment is insufficient, the threshold for recurrence is low (Citation7). In recent years, several promising molecules have been identified as potential targets for the treatment of itch in BP, including the type 2 cytokines IL-13 and IL-31, IgE, eosinophils, substance P and its receptor, neurokinin 1, OSM-R ß, and periostin (Citation89). Omalizumab, for instance, is a humanized monoclonal antibody that selectively binds to IgE and has demonstrated a rapid amelioration of BP-associated pruritus in just a few days (Citation96). There is thus a great opportunity for the development of novel agents. Further, the use of currently available targeted biological therapy has demonstrated efficacy in alleviating the burden of pruritus in patients with BP and should be considered in the guidelines of treatment (Citation106,Citation107).

6.2. Dermatitis herpetiformis

Dermatitis herpetiformis (DH) is a cutaneous manifestation of gluten sensitivity and celiac disease that affects 0.01–0.075% of the U.S. and European populations (Citation108,Citation109). Of note, DH only occurs in about 10–25% of individuals with celiac disease (CD), which occurs in about 1.4% of the population (Citation110). Further, DH presents in males 1.5 − 2 times as often as in females and is very uncommon among Asian and African American individuals (Citation111). DH presents with severely pruritic papulovesicles with overlying excoriation that are symmetrically located on the extensor surfaces, scalp, back, and buttocks (Citation108,Citation112). Importantly intense pruritus is such a strong leading symptom in DH and a complaint of nearly all affected patients, that its absence suggests an alternative etiology (Citation113). The pruritus may even occur several hours to months before the appearance of skin lesions and greatly diminishes the quality of life (Citation113).

Several challenges impede the treatment of DH, beginning with the pathophysiology of pruritus. While the general cause of DH is well-known to be due to circulating autoantibodies against tissue and epidermal transglutaminase (TG2 and TG3) triggered by dietary gluten, the cause of pruritus is much more ambiguous (Citation112). There are likely multiple pathways involved, including neurogenic inflammation, dysesthesia, and the release of inflammatory cytokines (Citation113). Recent studies have reported evidence supporting the role of Th2-type cytokines in DH. A subsequent study demonstrated an elevated concentration of IL-31 specifically in the serum and skin (Citation114). Given the well-known role of IL-31 in chronic pruritus and type 2 inflammation, it is highly possible that it also contributes to the itch in DH (Citation113). Additional research is needed to confirm this finding.

First-line management of DH is well-established and is centered on a strict gluten-free diet with supplemental dapsone or other sulfonamides for control of flares (Citation113). Unfortunately, a change in diet may take several months to control DH. Dapsone works quickly to resolve pruritus and prevent new blister formation, however, if the underlying disease is not already diet-controlled and medication is halted, the return of symptoms and rash within 48 hours is nearly inevitable (Citation112). Moreover, dapsone poses a risk of methemoglobinemia and hemolysis and requires workup for glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency in all patients. There is thus a great unmet need for additional non-dietary therapeutic strategies to provide fast-acting relief and long-term effects for patients. The development of targeted therapies, particularly concerning IL-31, may improve the pruritus burden associated with DH (Citation113).

7. Pruritic connective tissue diseases

Cutaneous autoimmune connective tissue diseases (ACTDs) represent a heterogeneous group of multisystemic disorders that heavily involve the skin. Pruritus is one of the most common symptoms and is reported in 57% of patients with autoimmune CTDs, regardless of the diagnosis (Citation115). The clinical findings of many of these conditions are overlapping, and in such cases, the prominence of pruritus may serve as a distinguishing factor (Citation116). Despite its prevalence, itch in CTDs is under-evaluated and under-treated (Citation115).

7.1. Scleroderma

Scleroderma is a group of rare diseases that causes chronic fibrosis of the skin and internal organs. Scleroderma can be localized, known as morphea, or systemic, known as systemic sclerosis (SSc) (Citation117). Very little information is available on the prevalence of pruritus in morphea, although its intensity is lower than in other ACTDs (Citation117). Conversely, pruritus in SSc has been well-established, with a prevalence ranging from 40–60% (Citation118–121). Itch has repeatedly been described as the most troublesome skin symptom of early cutaneous SSc. (). The severity of itch in SSc is correlated with certain aspects of QOL, including sleep, difficulty concentrating, depressive symptoms, and fatigue (Citation119,Citation122). Interestingly, the presence of itch in SSc does not appear to be associated with common biomarkers of systemic disease, such as anti-nuclear antibodies and anti-double-stranded DNA antibodies (Citation119).

A major challenge in treating SSc-associated pruritus is that the underlying pathophysiology and triggers are poorly understood. To date, only symptomatic treatments are available. Emerging hypotheses posit that increased lysophosphatidic acid near unmyelinated nerve endings, small nerve fiber damage due to compression in late disease, and pro-fibrotic activity of cannabinoid receptor CB2 may contribute to itch in SSc (Citation120,Citation123,Citation124). Opiate-mediated neurotransmission may also play a role and some case series demonstrate the anti-pruritic effect of low-dose naloxone and naltrexone (Citation125,Citation126). The default choice for cutaneous symptoms is immunosuppression with the typical agents used in inflammatory diseases, including methotrexate (MTX) and mycophenolate mofetil (MMF), which have antipruritic effects (Citation127). Nonetheless, there is evidence to show that patients receiving these therapies continue to experience itch, posing the question of whether there may be a neuropathic origin to the scleroderma-associated itch (Citation119). Glucocorticoids may also reduce itch, however they carry a risk for scleroderma renal crisis and should be used with caution (Citation128). There is a substantial unmet need for additional studies on treating pruritus in systemic sclerosis. Importantly, studies using skin symptoms as primary outcome measures are greatly lacking. While pruritus in SSc may not be life-threatening like the cardiorespiratory and renal involvement, it still bears importance as a predictor of morbidity and needs to be addressed (Citation128).

The lack of clinical trials and uncertain mechanisms of itch in SSc have further led to a lack of expert and evidence-based recommendations. While many drugs have been FDA-approved to target specific manifestations of SSc, predominantly interstitial lung disease, there does not appear to be a consensus in the literature on treating pruritus (Citation129,Citation130). Two sets of guidelines exist for the treatment of systemic sclerosis: the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) and the British Society for Rheumatology/British Health Professionals in Rheumatology (BSR/BHPR). The BSR/BHPR provides one class III recommendation for itch in SSc using antihistamines, while EULAR does not include itch as a symptom of SSc at all (Citation131,Citation132). This demonstrates the striking gap in awareness of pruritus in patients with SSc.

7.2. Dermatomyositis

Dermatomyositis (DM) is an inflammatory autoimmune disease characterized by muscle weakness, skin rashes, and lung involvement. The cutaneous manifestations of DM negatively impact QOL, perhaps even more so than in other severely pruritic conditions, such as AD and psoriasis (Citation133). Further, the improvement of cutaneous disease activity is associated with improved QOL (Citation134). The prevalence of itch in dermatomyositis is incredibly significant. At least 50–90% of the patient population has noted pruritus, even when muscle involvement is well-controlled. () (Citation115,Citation116). Compared to other CTDs including systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), Sjogren syndrome, SSc, and mixed CTD, DM has the highest rate of pruritus (Citation115). Pruritus tends to be especially prominent in the scalp in patients with DM and may be the initial presenting symptom (Citation135).

The treatment of itch in DM is therefore a top priority, although there are currently no concrete therapeutic guidelines (Citation124). A substantial hurdle to managing cutaneous DM is that symptoms like pruritus are often more resistant to therapy than muscle involvement. Traditional treatment with antimalarial medications alone is often not sufficient, and thus secondary agents such as cytotoxic agents and IVIG are needed (Citation136). There is also a lack of data from RCTs using consistent, validated measures of cutaneous response to therapy (Citation135). Many clinical trials focus on muscle involvement as an outcome measure, thereby limiting our knowledge of antipruritic effects.

The pathophysiology of pruritus in DM is not entirely understood, although it is thought to be inflammatory, and increased IL-31 may play a driving role (Citation116). This suggests that immunosuppressants could be a valuable option, although conventional anti-inflammatory regimens have not been universally effective. Strides have been taken in recent years to illuminate non-immunosuppressing medications for treating itch in DM. For instance, a synthetic cannabinoid receptor type 2 agonist, lenabasum, downregulates IL-31 and IL-4 in addition to other inflammatory cytokines. It has demonstrated antipruritic efficacy in refractory cutaneous DM and diffuse SSc in phase 2 trials (Citation116). Unfortunately, lenabasum failed to meet the primary endpoint in subsequent phase 3 testing (Citation137,Citation138).

8. Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma

Cutaneous T-cell lymphomas (CTCLs) are a rare group of lymphoproliferative disorders that are highly associated with pruritus, with a prevalence reaching 88% (Citation139,Citation140). CTCL may be classified into various subtypes, including Sézary syndrome (SS) and mycosis fungoides (MF). SS and MF are the most common forms and tend to present with the most severe itch, requiring specific treatment outside of the designated lymphoma regimen (Citation15). Importantly, this pruritus is usually long-lasting and refractory to conventional antipruritic therapy, such as topical corticosteroids and oral antihistamines (Citation15). Moreover, pruritus in CTCL has numerous aggravating factors, including heat, water, and nocturnal worsening, which contribute to its burden on quality of life, especially sleep and mental health (Citation141). Despite pruritus being well-established as the most frequent and earliest-appearing sign of CTCL, it may occur without lesions or other symptoms, making timely diagnosis difficult (Citation141). The pruritus associated with CTCL generally increases in severity as the disease progresses, and therefore early intervention is critical.

The last decade of CTCL research has brought great advances in understanding the pathophysiology contributing to itch. Notably, the Th2 cytokine, IL-31, has been found to be increased in the serum of patients with CTCL in multiple studies as well as in the epidermis and dermal infiltrate of those with pruritus (Citation142–144). An increased expression of the IL-31 receptors, IL-31RA and oncostatin M receptor beta (OSMRβ), has also been reported in the epidermis of itchy CTCL patients (Citation142). Although a recent study by Van Santen et al. was unable to confirm these results, the consistent evidence presented by Nattkemper et al. and Abreu et al. provides strong support for the association of IL-31 with CTCL (Citation142,Citation143,Citation145). Furthermore, the elevated level of IL-31 has demonstrated a correlation with itch severity, and improvement in pruritus led to IL-31 reduction, thus supporting its role as a valuable biomarker (Citation146,Citation147). Mogalizumab, a novel monoclonal antibody targeting the chemokine receptor type 4, significantly reduced pruritus and decreased IL-31 expression, further supporting this association (Citation146). According to the most up-to-date literature, cytokine receptors, mas-related G-protein coupled receptors, and TRP channels appear to be of likely importance and should be explored further (Citation148).

The backbone of treatment for pruritus in CTCL is high-potency TCS, although other topical therapies are emerging. For instance, mu-opioid receptor antagonists, such as naltrexone and naloxone, have demonstrated successful reduction of pruritus in CTCL patients (Citation148). In the last decade, we have identified several pruritus-associated mediators and their receptors that may play a role in CTCL, including chemokines and cytokines, proteases, and neuropeptides (Citation142,Citation148). Despite recent advances, the underlying pathophysiology of pruritus in CTCL is not entirely clear. Overall, treating itch in CTCL is difficult and thus far has systemically focused on controlling the general lymphoma. There is a desperate need for specific itch-targeted therapies to provide relief to these patients. Notably, mogamulizumab is one of the few drugs that has been studied for its antipruritic effect and recently received FDA approval (Citation149). Other approved therapies that have demonstrated relief of itch in CTCL include romidepsin, bexarotene, and vorinostat, among others (Citation150,Citation151). Despite inconsistent evidence described above, there is still great interest in evaluating the potential benefit of targeting the IL-31 pathway in CTCL patients with pruritus (Citation152). Additionally, naloxone hydrochloride 0.5% lotion has been evaluated in a phase III trial in which the primary endpoint assessed was a change from baseline itch NRS (NCT02811783). This novel investigational agent was granted orphan drug status and fast track designation from the FDA in 2010 and 2013, respectively, and results are highly anticipated.

9. Pruritus following injury and infection

9.1. Post-burn itch

Pruritus during the process of healing from burns is a complaint in nearly all (87–93%) recovering patients (Citation153). The itching is frequently described as persistent, unrelenting, and unpredictable with variability dependent on environmental context (Citation154). Awareness of this problem was minimal until relatively recently, leaving many patients to suffer in silence (Citation153,Citation155). Post-burn pruritus can persist extensively after healing from injury, as demonstrated in a cross-sectional study of burn survivors in which 72% and 44% of individuals continued to experience itch after 17 and 30 years, respectively (Citation156). Treating pruritus in burn survivors is obstructed by an incomplete understanding of the pathophysiology as well as a lack of validated tools to measure treatment efficacy. When skin is injured with thermal trauma, as in burns, there is a significant impact on mast cells, leading to the release of plasma histamine, free radicals, and well as many local neuropeptides and pruritogenic, inflammatory mediators (Citation157–159). These substances bind to peripheral C fiber receptors and transmit itch information. The mechanism of itch in post-burn patients also appears to have neuropathic aspects that may be more prominent than the pruritogenic components (Citation154).

Several treatments are available to improve the symptoms of pruritus in post-burn patients, though there does not seem to be a consistent algorithm for management. Historically, the mainstay of treatment has been antihistamines and emollients. However, there is evidence to show that antihistamines are largely ineffective in post-burn pruritus (Citation153,Citation155,Citation160). Other systemic agents that have shown antipruritic efficacy include pregabalin and gabapentin, which interestingly, were shown to be more effective and faster-acting than cetirizine (95% reduction in VAS score compared to 52%, respectively) (Citation160–162). In 2010, a multidisciplinary panel used the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) classification to assess therapeutic agents for post-burn pruritus (Citation163). At that time, 16 of the 23 studies analyzed were observational. First-line recommendations were antihistamines and gabapentin, with ondansetron and loratadine as second-line options (Citation163). Of note, there have been very few additional controlled studies added to the literature since then. Moreover, a recent systematic review and meta-analysis found that current interventions do not achieve clinically significant reduction in pruritus (Citation164). There is thus an urgent need for a well-established therapeutic approach to post-burn pruritus that is refractory to first-line agents. Some of the agents of great interest target the debilitating hypertrophic scars that develop during healing and are associated with itch. Physical maneuvers such as massaging may be an effective therapy, in addition to laser therapy, which may reduce itch by decreasing vascularity in the associated capillaries (Citation165,Citation166).

9.2. Keloids

Keloids are scars that result after cutaneous injury. Unlike traditional scars, keloids extend beyond the margins of the insult and often present as raised, pigmented lesions with pain and pruritus (Citation167). Several studies have confirmed that pruritus is incredibly common in keloids, presenting as a symptom in 67–95% () (Citation168–170). Of note, keloids also disproportionally affect African American patients, who report a greater association of pruritic keloids compared to other populations (Citation171). The high prevalence of keloid-associated pruritus illuminates the urgent need for increased awareness and prioritization of treating this complaint in dermatology practice.

The mechanisms underlying pruritic keloid formation are thought to be multifactorial, involving type 2 inflammation with increased dermal mast cell density, pro-fibrotic cytokines, and small C-fiber neuropathy (Citation168,Citation172). Treatments for keloids are abundant, ranging from topical steroids, antibiotics, and 5-fluorouracil to intralesional agents such as cytotoxins, botulinum, and immune-response modifiers, as well as laser therapy, cryotherapy, radiotherapy, and excision (Citation173). Despite the broad therapeutic scope, many of these studies focus on halting the proliferation of the keloid but have not measured or reported a reduction in pruritus as a study endpoint (Citation167). Conversely, others focus on symptom control, such as pruritus, but do not alter the underlying process driving keloid formation (Citation167). Given a high recurrence rate of >45% in surgically excised lesions, addressing the root process is critical (Citation174). There is thus an urgent need for keloid therapies that measure the efficacy of altering the mechanisms underlying keloids as well as their associated itch. Innovational multimodal approaches using a combination of therapies listed have shown promising results with respect to clinical efficacy, low recurrence rate, and minimal adverse effects (Citation175–177). Large-scale trials investigating the antipruritic effects of such approaches are of paramount importance.

9.3. Scabies and post-scabetic syndrome

Scabies itch is the intense, pruritic sensation that occurs with the infestation of the Sarcoptes scabiei mite and is frequently described as ‘the worst itch ever’ (Citation178). The presence of pruritus is reported in 90–99% of cases according to the literature () (Citation179). According to a study of scabies itch in 82 subjects, the average itch intensity is severe, (7.2/10) and lasted about 3 months before reaching a proper diagnosis and initiating treatment (Citation180). This illuminates the unmet need for early diagnosis. Notably, there is a profound impact on QOL, and especially on sleep quality, which may be attributed to the worsened severity of scabies itch during the night (Citation181). In addition to causing grave discomfort, scabies itch can also lead to a host of consequences including entry of pathogens from excoriation injuries, stigmatization, and psychosocial and economic burden (Citation178). It is of utmost importance for providers to recognize that itch is present in nearly all scabies patients and must be addressed (Citation179).

The mechanism of itch in scabies is thought to involve both immediate and delayed hypersensitivity reactions, but may also be attributed to components of host-mite interaction, secondary microbial infections, and neural sensitization (Citation178). Specific molecules that are proposed to play a key role in this process include keratinocytes, mast cells, and protease release from the scabies mite (Citation178). As such, primary management of scabies itch relies on removing the scabies mites and their eggs. Despite the use of scabicides, scabies itch is often persistent and may even be aggravated with the destruction of the mites (Citation182). Antihistamines have long been used to treat the remnants of scabies itch, however, these agents have no effect as scabies itch is mediated by non-histaminergic itch fibers (Citation183). There is thus an urgent need for additional therapies to manage itch in post-scabetic patients. Emerging therapeutic targets of interest include the protease-activated receptor-2 and the Mas-related G-protein-coupled receptor X2, which are both present on mast cells (Citation178). In addition, it is relevant to keep in mind the economic cost of treating scabies, especially given its geographic prevalence in third-world countries.

10. Genodermatoses

Ichthyosis, palmoplantar keratodermas (PPK), and epidermolysis bullosa (EB) are three of the most common hereditary skin diseases, with a prevalence of 25%, 13%, and 7%, respectively (Citation184). These genodermatoses are highly associated with pruritus. Of note, the conditions discussed in this section may also be acquired later in life due to various etiology outside of genetics. For the purpose of this article, we will only be focusing on the inherited forms.

10.1. Epidermolysis bullosa

EB presents as fragile skin with widespread blistering, erosions, and scaring, as well as lesions on the mucous membranes, when severe (Citation185). EB is classified into simplex, junctional, and dystrophic subtypes based on specific gene mutations involved in the maintenance of dermal-epidermal structural and functional integrity (Citation186). To date, up to 20 different causative genes have been identified and new genes continue to be discovered (Citation187). This review will focus on dystrophic EB, specifically recessive dystrophic EB (RDEB), which causes patients to experience the most itch compared to other forms of EB (Citation188). In a comprehensive study of 50 individuals with RDEB, 93% endorsed itch in the previous month, of which just over half were using medication to treat the itch (Citation189). The itch associated with RDEB has been described similarly in severity to that of AD, PN, and chronic urticaria (Citation190,Citation191). It occurs predominantly in areas of healing wounds and the surrounding skin and repeated scratching contributes to a persistent, vicious, itch-scratch cycle (Citation191). This illuminates the debilitating impact of itch in RDEB and the need for personalized, effective treatments.

RDEB is caused by mutations in the collagen type VII alpha 1 chain (COL7A1) gene (Citation191). There is no known cure for any of the subtypes of EB. Existing therapies aim to control itch and pain, promote wound healing, and prevent complications (Citation187). There is only one topical therapy that has been approved for dystrophic EB: beremagene geperpavec (B-VEC), a gene replacement therapy delivering human COL17A1 (Citation192,Citation193). B-VEC led to faster wound healing than the placebo, although its antipruritic effect was not explicitly explored (Citation194). Evidence from some studies has also demonstrated a reduction of itching with the topical agents SD-1-1 (6% allantoin), calcipotriol, diacerein 1% ointment, and henna (Citation195–197). However, none of these agents are incredibly effective, and they do not alter the underlying disease process. In addition, the severe types of EB involve internal organs, requiring a systemic approach (Citation197). Therefore, there is a paramount unmet need to develop new therapeutic options to control itch in dystrophic EB. A case-control study recently demonstrated that there is prominent Th2 signaling in the lesional skin of dystrophic EB pruriginosa (EBP), suggesting that targeting mediators of type 2 inflammation may be a promising strategy for treating itch in DEB (Citation198). These findings are supported by anecdotal reports, particularly a case of EBP that improved following treatment with dupilumab (Citation199). Another promising treatment on the horizon is the technology of gene editing and RNA to correct mutations at their endogenous loci, as opposed to replacing the function of the mutant gene as described above (Citation197). This form of precision medicine would eliminate the risk of mutations resulting from random transgene integrations. Additional novel emerging treatments include cell-based therapy with mesenchymal stem cells, fibroblasts, and induced pluripotent stem cells, as well as protein replacement therapy (Citation197). While these approaches are somewhat more feasible to conduct systemically than gene therapy, they do not offer long-term correction.

10.2. Ichthyosis

Ichthyosis is comprised of a wide array of rare genetic diseases caused by over 50 distinct genes that impact skin barrier function (Citation200). Ichthyosis usually presents at birth or early in life with generalized hyperkeratosis, variable erythema, and scaling, itchy skin (Citation201). Until a few years ago, no clinical studies had evaluated the burden of itch in ichthyosis. A multicenter study of 94 patients with several different disease subtypes found that itch occurred in 93% of all patients, with 63% reporting that it was often or always present () (Citation202). This illuminates a critical need for pediatric providers to be educated on the signs and symptoms of ichthyosis, allowing for early diagnosis with genetic testing if desired, and a discussion on treatment.

Here we discuss the forms of ichthyosis that are thought to have the most robust itch profiles. Ichthyosis vulgaris (IV) is caused by loss-of-function mutations in the filaggrin gene that lead to a lack of natural moisturizing factors (Citation203). A large portion of patients with this condition also suffer from eczema, and experience substantial itch. Few emerging treatments have demonstrated antipruritic effects against IV in recent years, one of which is topical 7.5–10% urea (Citation204,Citation205). Lamellar ichthyosis (LI) is another form of this burdensome disease that is highly pruritic and commonly caused by a mutation in the gene encoding transglutaminase 1 (Citation206). It presents at birth with a tight, clear collodion membrane covering the body that peels away and leaves behind large scales (Citation206). Netherton syndrome, a rare autosomal recessive disorder caused by mutations in the serine protease inhibitor Kazal-type 5 (SPINK5) gene, appears to be the branch of ichthyosis with the highest frequency, severity, and duration of itch (Citation202). These parameters have been reported as comparable to those that present in atopic dermatitis and may lead to its misdiagnosis (Citation202). Netherton syndrome characteristically presents with a triad of ichthyosiform erythroderma, hair shaft abnormalities with thin, fragile, hair, and immune dysregulation (Citation207).

Despite increasing progress in understanding the mechanisms underlying ichthyoses, no cure has been found. First-line therapy for ichthyosis consists of topical compounds that aim to increase hydration, moisturization, and keratolysis (Citation208). While these agents often reduce itch, they may be difficult to apply if large body surface areas are involved. Systemic therapy is currently centered on oral retinoids, although this is not a viable option for all patients given its side effect profile and teratogenicity (Citation208). Given these barriers, there remains an unmet need for novel formulations to treat ichthyoses. Fortunately, there is an abundance of exciting work cumulating in the field of replacement therapy using nanotechnology, gene therapy, and reprofiling of biological and chemical drugs, that may potentially transform the management of ichthyoses (Citation209,Citation210).

10.3. Hereditary keratodermas

Palmoplantar keratoderma is a group of heterogenous cutaneous diseases that presents with hyperkeratosis of the palms and soles caused by mutations in up to 45 genes encoding the proteins involved in cornification (Citation211,Citation212). This is the process of keratinocytes undergoing terminal differentiation and programmed cell death to form the outermost skin barrier. Similar to the other genodermatoses, PPK is not life-threatening, although it impairs quality of life due to pain, itching, and reduced mobility. Lesions can also become infected and malodorous.

The degree of pruritus is widely varied; however, it appears to be more severe in syndromic PPK (Citation213). Olmsted syndrome, for instance, is a genetic disorder characterized by PPK and periorificial lesions, in addition to potential systemic involvement of other organs (Citation214). Olmsted syndrome is considered to be extremely itchy and is related to a gain-of-function mutation in the TRPV3 itch-sensitive ion channel (Citation215). Pruritus has been reported in about 16% of cases worldwide, although this estimate is limited to case report data (Citation215). The itch associated with PPK is especially detrimental with regard to developing insomnia and difficulty with walking and grasping (Citation215). Diagnosis is often clinical but may require molecular and genetic studies, which are high in cost. This may hinder appropriate diagnosis, genetic counseling, and management in resource-poor clinical settings (Citation211). PPK is incurable, and available treatments for itch are lacking, offering only temporary or partial relief of symptoms. Furthermore, topical therapies are cumbersome to maintain. Targeting the underlying pruritic course of disease in PPK is thus of great interest. The use of targeted gene therapy against the autosomal dominant forms, such as TRPV3 antagonists (KM-001) and inhibitors of epidermal growth factor receptor (erlotinib), may be an effective therapeutic approach (Citation215,Citation216). Additional research is needed to assess the burden of pruritus in PPK and evaluate effective management.

11. Conclusion

Pruritus affects a significant patient population across a wide spectrum of diseases. The effective treatment of itch has made impressive progress in recent years regarding a select group of common dermatoses. However, numerous conditions associated with debilitating pruritus remain underrecognized and dramatically impact quality of life. We emphasized the burden of several autoimmune, genetic, and generalized chronic forms of pruritus, as well as their barriers to treatment. There is a desperate need for increased awareness of pruritus in these conditions to facilitate early diagnosis. Increased understanding of underlying pathophysiology is of utmost importance to identifying therapeutic targets. Additional randomized studies are warranted to evaluate the antipruritic impact of novel treatments and new indications of existing agents.

Disclosure statement

Dr. Gil Yosipovitch has received funding or grants from Sanofi, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc., Pfizer, Escient Health, Novartis, Eli Lilly, Celldex, and Kiniksa Pharmaceuticals. He has participated on a Data Safety Monitoring/Advisory board and received consulting support from Abbive, Arcutis, Escient Health, Eli Lilly, Galderma, LEO Pharma, Novartis, Pfizer, Pierre Fabre, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc., Sanofi, Trevi Therapeutics, Vifor, Kamari, Kiniksa, and GSK. Patents include Topical Acetaminophen Formulations for Itch Relief.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Hay RJ, Johns NE, Williams HC, et al. The global burden of skin disease in 2010: an analysis of the prevalence and impact of skin conditions. J Invest Dermatol. 2014;134(6):1–23. doi:10.1038/jid.2013.446.

- Pereira MP, Ständer S. Assessment of severity and burden of pruritus. Allergology International. 2017;66(1):3–7. doi:10.1016/j.alit.2016.08.009.

- Lobefaro F, Gualdi G, Di Nuzzo S, et al. Atopic dermatitis: clinical aspects and unmet needs. Biomedicines. 2022;10(11):2927. doi:10.3390/biomedicines10112927.

- Silverberg JI, Mohawk JA, Cirulli J, et al. Burden of disease and unmet needs in atopic dermatitis: results from a patient survey. Dermatitis. 2023;34(2):135–144. doi:10.1089/derm.2022.29015.jsi.

- Buhl T, Werfel T. Atopic dermatitis - perspectives and unmet medical needs. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2023;21(4):349–353.

- Kolkhir P, Akdis CA, Akdis M, et al. Type 2 chronic inflammatory diseases: targets, therapies and unmet needs. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2023;22(9):743–767. doi:10.1038/s41573-023-00750-1.

- Ujiie H, Rosmarin D, Schön MP, et al. Unmet medical needs in chronic, non-communicable inflammatory skin diseases. Front Med (Lausanne). 2022;9:875492. doi:10.3389/fmed.2022.875492.

- Ständer S, Stumpf A, Osada N, et al. Gender differences in chronic pruritus: women present different morbidity, more scratch lesions and higher burden. Br J Dermatol. 2013;168(6):1273–1280. doi:10.1111/bjd.12267.

- Kursewicz C, Fowler E, Rosen J, et al. Sex differences in the perception of itch and quality of life in patients with chronic pruritus in the United States. Itch. 2020;5(3):e41–e41. doi:10.1097/itx.0000000000000041.

- Peters MG, Di Bisceglie AM, Kowdley KV, et al. Differences between Caucasian, African American, and Hispanic patients with primary biliary cirrhosis in the United States. Hepatology. 2007;46(3):769–775. doi:10.1002/hep.21759.

- Nzerue CM, Demissochew H, Tucker JK. Race and kidney disease: role of social and environmental factors. J Natl Med Assoc. 2002;94(8 Suppl):28s–38s.

- Galderma announces regulatory filing acceptance for its investigational treatment in prurigo nodularis and atopic dermatitis in the U.S. and EU; February 14, 2024 [press release].

- Han Y, Woo YR, Cho SH, et al. Itch and Janus Kinase Inhibitors. Acta Derm Venereol. 2023;103:adv00869. doi:10.2340/actadv.v103.5346.

- Fourzali K, Yosipovitch G. Safety considerations when using drugs to treat pruritus. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2020;19(4):467–477. doi:10.1080/14740338.2020.1728252.

- Farrah G, Spruijt O, McCormack C, et al. A systematic review on the management of pruritus in patients with cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Itch. 2021;6(2):e55–e55. doi:10.1097/itx.0000000000000055.

- Kim BS, Berger TG, Yosipovitch G. Chronic pruritus of unknown origin (CPUO): uniform nomenclature and diagnosis as a pathway to standardized understanding and treatment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81(5):1223–1224. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.07.080.

- Roh YS, Choi J, Sutaria N, et al. Itch: epidemiology, clinical presentation, and diagnostic workup. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86(1):1–14. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.07.076.

- Okano M, Hirahara K, Kiuchi M, et al. Interleukin-33-activated neuropeptide CGRP-producing memory Th2 cells cooperate with somatosensory neurons to induce conjunctival itch. Immunity. 2022;55(12):2352–2368.e2357. doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2022.09.016.

- Wang F, Kim BS. Itch: a paradigm of neuroimmune crosstalk. Immunity. 2020;52(5):753–766. doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2020.04.008.

- Wang F, Trier AM, Li F, et al. A basophil-neuronal axis promotes itch. Cell. 2021;184(2):422–440.e417. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2020.12.033.

- Nattkemper LA, Kim BS, Yap QV, et al. Increased systemic levels of centrally acting B-type Natriuretic Peptide are associated with chronic Itch of different types. J Invest Dermatol. 2024. doi:10.1016/j.jid.2024.02.026.

- Ju T, Labib A, Vander Does A, et al. Therapeutics in chronic pruritus of unknown origin. Itch. 2023;8(1):e64–e64. doi:10.1097/itx.0000000000000064.

- Kwatra S, Bordeaux Z, Pritchard T, et al. Efficacy, safety, and mechanism of action of abrocitinib in the treatment of prurigo nodularis and chronic pruritus of unknown origin. Presented at: European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology Congress 2023; 2023 October 11-14, Berlin, Germany.

- Valdes-Rodriguez R, Mollanazar NK, González-Muro J, et al. Itch prevalence and characteristics in a Hispanic geriatric population: a comprehensive study using a standardized itch questionnaire. Acta Derm Venereol. 2015;95(4):417–421.

- Gunalan P, Indradevi R, Oudeacoumar P, et al. Pattern of skin diseases in geriatric patients attending tertiary care centre. jemds. 2017;6(20):1566–1570. +. doi:10.14260/Jemds/2017/344.

- Yalçin B, Tamer E, Toy GG, et al. The prevalence of skin diseases in the elderly: analysis of 4099 geriatric patients. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45(6):672–676. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2005.02607.x.

- Silverberg JI, Hinami K, Trick WE, et al. Itch in the general internal medicine setting: a cross-sectional study of prevalence and quality-of-life effects. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2016;17(6):681–690. doi:10.1007/s40257-016-0215-3.

- Chung BY, Um JY, Kim JC, et al. Pathophysiology and treatment of pruritus in elderly. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(1):174. doi:10.3390/ijms22010174.

- Garibyan L, Chiou AS, Elmariah SB. Advanced aging skin and itch: addressing an unmet need. Dermatol Ther. 2013;26(2):92–103. doi:10.1111/dth.12029.

- Bellinato F, Maurelli M, Gisondi P, et al. Clinical features and treatments of transient acantholytic dermatosis (Grover’s disease): a systematic review. J Deutsche Derma Gesell. 2020;18(8):826–833. doi:10.1111/ddg.14202.

- Aldana PC, Khachemoune A. Grover disease: review of subtypes with a focus on management options. Int J Dermatol. 2020;59(5):543–550. doi:10.1111/ijd.14700.

- Gantz M, Butler D, Goldberg M, et al. Atypical features and systemic associations in extensive cases of Grover disease: a systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77(5):952–957.e951. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.06.041.

- Fourzali KM, Yosipovitch G. Management of itch in the elderly: a review. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2019;9(4):639–653. doi:10.1007/s13555-019-00326-1.

- Shevchenko A, Valdes-Rodriguez R, Yosipovitch G. Causes, pathophysiology, and treatment of pruritus in the mature patient. Clin Dermatol. 2018;36(2):140–151. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2017.10.005.

- Pisoni RL, Wikström B, Elder SJ, et al. Pruritus in haemodialysis patients: international results from the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study (DOPPS). Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2006;21(12):3495–3505. doi:10.1093/ndt/gfl461.

- Schut C, Mollanazar NK, Kupfer J, et al. Psychological interventions in the treatment of chronic itch. Acta Derm Venereol. 2016;96(2):157–161. doi:10.2340/00015555-2177.

- Bin Saif GA, Ericson ME, Yosipovitch G. The itchy scalp–scratching for an explanation. Exp Dermatol. 2011;20(12):959–968. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0625.2011.01389.x.

- Rattanakaemakorn P, Suchonwanit P. Scalp pruritus: review of the pathogenesis, diagnosis, and management. Biomed Res Int. 2019;2019:1268430–1268411. doi:10.1155/2019/1268430.

- Misery L, Ständer S, Szepietowski JC, et al. Definition of sensitive skin: an expert position paper from the special interest group on sensitive skin of the international forum for the study of itch. Acta Derm Venereol. 2017;97(1):4–6.

- Misery L, Rahhali N, Ambonati M, et al. Evaluation of sensitive scalp severity and symptomatology by using a new score. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25(11):1295–1298. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3083.2010.03968.x.

- Choragudi S, Andrade L, Yosipovitch G. Genital pruritus is associated with longer hospital stays, higher costs and increased odds of psychiatric hospitalization among inpatient adults with pruritus in the United States—National inpatient sample (2012–2015). JEADV Clinical Practice. 2023;3(1):233–238. doi:10.1002/jvc2.281.

- Hadasik K, Arasiewicz H, Brzezińska-Wcisło L. Assessment of the anxiety and depression among patients with idiopathic pruritus ani. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2021;38(4):689–693. doi:10.5114/ada.2021.108906.

- Schubert MC, Sridhar S, Schade RR, et al. What every gastroenterologist needs to know about common anorectal disorders. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15(26):3201–3209. doi:10.3748/wjg.15.3201.

- Swamiappan M. Anogenital pruritus - an overview. J Clin Diagn Res. 2016;10(4):We01-03–WE03. doi:10.7860/JCDR/2016/18440.7703.

- Parés D, Abcarian H. Management of common benign anorectal disease: what all physicians need to know. Am J Med. 2018;131(7):745–751. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2018.01.050.

- Daniel GL, Longo WE, Vernava AM.3rd. Pruritus ani. Causes and concerns. Dis Colon Rectum. 1994;37(7):670–674. doi:10.1007/BF02054410.

- Jakubauskas M, Dulskas A. Evaluation, management and future perspectives of anal pruritus: a narrative review. Eur J Med Res. 2023;28(1):57. doi:10.1186/s40001-023-01018-5.

- Rosen JD, Fostini AC, Yosipovitch G. Diagnosis and management of neuropathic itch. Dermatol Clin. 2018;36(3):213–224. doi:10.1016/j.det.2018.02.005.

- Cohen AD, Vander T, Medvendovsky E, et al. Neuropathic scrotal pruritus: anogenital pruritus is a symptom of lumbosacral radiculopathy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52(1):61–66. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2004.04.039.

- Felemovicius I, Ganz RA, Saremi M, et al. SOOTHER TRIAL: observational study of an over-the-counter ointment to heal anal itch. Front Med (Lausanne). 2022;9:890883. doi:10.3389/fmed.2022.890883.

- Weichert GE. An approach to the treatment of anogenital pruritus. Dermatol Ther. 2004;17(1):129–133. doi:10.1111/j.1396-0296.2004.04013.x.

- Albuquerque A. Anal pruritus: don’t look away. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2024;16(3):112–116. doi:10.4253/wjge.v16.i3.112.

- Jia W, Li Q, Ni J, et al. Efficacy and safety of methylene blue injection for intractable idiopathic pruritus ani: a single-arm metaanalysis and systematic review. Tech Coloproctol. 2023;27(10):813–825. doi:10.1007/s10151-023-02825-y.

- Yang EJ, Murase JE. Recalcitrant anal and genital pruritus treated with dupilumab. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2018;4(4):223–226. doi:10.1016/j.ijwd.2018.08.010.