Abstract

Purpose

Providers who treat patients with psoriasis are unevenly distributed across the United States, with more in urban than rural areas. This retrospective claims analysis characterized disparities in access to care for US patients with psoriasis using data from the STATinMED database.

Materials and methods

Patients (≥18 years) had ≥1 claim with a psoriasis diagnosis and ≥1 claim for advanced psoriasis therapy (apremilast or biologics) between January 2015 and December 2019. Access to psoriasis care was determined using the proportion of patients with 0, 1–2, 3–4, or ≥5 providers in their local area.

Results

Overall, 179,688 patients were included in the analysis, 80.0% in urban areas. The access ratio was highest for internal medicine physicians (97.1 per 1000 patients) and lowest for dermatologists (4.4 per 1000 patients) and family practice physicians (3.9 per 1000 patients). In urban areas, 41% of patients had access to ≥5 dermatologists versus 7% in rural areas. Whereas 2% of patients in urban areas sought care outside of their local area, 75% in rural areas did so. Use of advanced therapies was low in all states (<17%).

Conclusion

Access to psoriasis-treating providers varied widely. Regardless of access, utilization of advanced treatments was low, suggesting the need for effective, easy-to-administer therapy.

Introduction

Psoriasis is a chronic, multisystem condition (Citation1). While topical medications or phototherapy are often adequate treatment for mild to moderate cases, patients with moderate to severe psoriasis require systemic treatment, which may include advanced nonbiologic and biologic therapies (Citation1). Obtaining these advanced therapies, however, may be challenging. A recent study determined that only 41% of all eligible patients with moderate to severe psoriasis in the United States received treatment. Of those who received treatment, 22% received biologics, 32% received traditional oral systemic therapy, and 42% of patients with moderate to severe psoriasis received only topical therapy (Citation2). Furthermore, approximately half of patients who received treatment allowed their prescriptions to lapse. For patients with psoriasis, lack of treatment and undertreatment for their psoriasis symptoms are common (Citation2).

Although psoriasis can be treated by various types of providers, including dermatologists, family/general practice physicians, internal medicine specialists, or nurse practitioners/physician assistants with a dermatology subspecialty, patients may need to seek care from dermatologists to access advanced biologic and nonbiologic therapies. Dermatologists, however, are distributed unevenly across the United States. Urban areas have higher concentrations of dermatology specialists compared with rural areas, and the disparity is increasing. Between 1995 and 2013, the urban–rural difference in dermatologist density grew from 3.41 per 100,000 people to 4.03 per 100,000 people. Not only is there a higher concentration of dermatologists in urban than in rural areas, but the dermatologists also tend to be younger (Citation3).

The difference in the urban–rural geographic density of all physicians also increased during the same period, rising from 220 per 100,000 to 257 per 100,000 (Citation3). While nurse practitioners and physician assistants may help improve access to care, these providers tend to be concentrated in urban areas (Citation3, Citation4). Persistent gaps in access to care in rural versus urban areas is likely to lead to increased wait times, affecting clinical outcomes and patients’ quality of life (Citation3).

To further explore current access to psoriasis-treating providers in urban and rural areas of the United States, a claims analysis of treatment patterns in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis was conducted. The objective of this study was to identify and characterize the geographic barriers and disparity in access to care for patients with psoriasis in the United States.

Methods

This retrospective, longitudinal, observational study used de-identified data from administrative commercial, Medicaid, and Medicare claims in the STATinMED all-payer database (STATinMED; Dallas, TX). This database contains medical and pharmacy claims from all provider types and sites of care (e.g., inpatient, outpatient, and accountable care organizations), and includes patients from all US geographical regions.

This study used de-identified claims data, meaning no patients were directly involved. Institutional review board approval and informed consent were not required.

All patients were adults aged 18 years or older who had ≥1 claim with a diagnosis of psoriasis and ≥1 claim for advanced psoriasis therapy (apremilast or biologics) between January 1, 2015, and December 31, 2019 (identification period). The index date was defined as the earliest date of a claim for an advanced psoriasis treatment on or after a psoriasis diagnosis during the identification period. All patients had ≥12 months of continuous health insurance enrollment before and after their index date.

Geographic type identification

The patient-specific geographic region was defined as the region in which the patent was enrolled in a health plan on the index date. States were categorized based on US Census Bureau region designations (Northeast: Connecticut, Massachusetts, Maine, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, and Vermont; North Central: Iowa, Illinois, Indiana, Kansas, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, North Dakota, Nebraska, Ohio, South Dakota, and Wisconsin; South: Alabama, Arkansas, Delaware, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maryland, Mississippi, North Carolina, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Virginia, and West Virginia; and West: Alaska, Arizona, California, Colorado, Hawaii, Idaho, Montana, New Mexico, Nevada, Oregon, Utah, Washington, and Wyoming).

Urban or rural designations were based on each patient’s ZIP code. Patients were assigned a 3-digit ZIP code prefix (referred to as zip3) based on the location of the healthcare provider they visited most frequently during the study period (January 1, 2014, through December 31, 2020). Urban or rural designations were assigned to each zip3 using the Health Resources and Services Administration Rural Assignments Identifiers (Citation5). The number of psoriasis-treating providers in each patient’s zip3 were identified and designated as either urban or rural based on the zip3. Psoriasis-treating providers were defined as those who had submitted claims for patients with a psoriasis diagnosis or who had prescribed advanced therapies for psoriasis. Advanced therapies include the biologics etanercept, infliximab, adalimumab, certolizumab pegol, ustekinumab, risankizumab, secukinumab, brodalumab, ixekizumab, guselkumab, and tildrakizumab and the oral phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitor apremilast (Citation6–17). Patient access to psoriasis-treating providers was determined by the proportion of patients with 0, 1–2, 3–4, or ≥5 providers in their zip3. If no provider was identified, the patient was designated as rural.

Results

Study population

A total of 179,688 patients with psoriasis met the inclusion criteria and were included in the analysis. The mean age was 58.5 years, 90.1% of patients were White, and 80.0% lived in an urban area (). Approximately half of patients had commercial health insurance, while 40% had Medicare. Nearly half of patients had an annual household income of less than $40,000.

Table 1. Demographics and patient characteristics.

Access to care

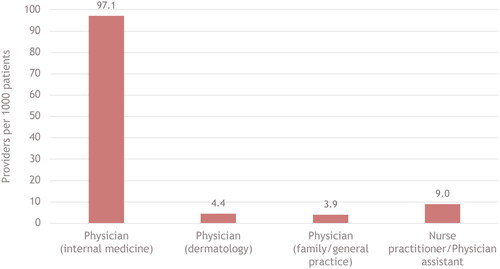

The ratio of providers to patients was highest for internal medicine physicians (97.1 per 1000 patients) and lowest for dermatologists (4.4 per 1000 patients) and family practice physicians (3.9 per 1000 patients; ). The ratio of nurse practitioners/physician assistants to patients fell above dermatologists, at 9.0%.

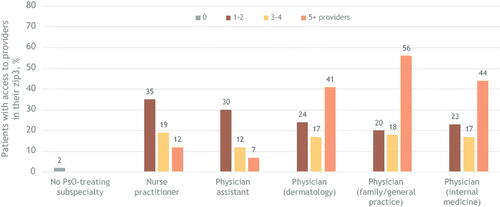

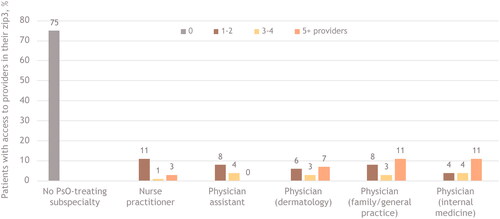

In both urban and rural areas, most psoriasis care was provided by dermatologists, family/general practice physicians, or internal medicine physicians, although access was markedly different. In urban areas, for example, 41% of patients had ≥5 dermatologists in their zip3, compared with 56% for ≥5 family/general practice physicians and 44% for ≥5 internal medicine physicians (). In comparison, in rural areas, only 7% of patients had ≥5 dermatologists in their zip3, whereas 11% had ≥5 family/general practice physicians or internal medicine physicians (). In urban areas, 12% of patients had access to ≥5 nurse practitioners and 7% had access to ≥5 physician assistants; in rural areas, those percentages dropped to 3% for nurse practitioners and 0% for physician assistants. Whereas 2% of patients in urban areas were treated by a provider outside of their zip3, 75% of those in rural areas sought psoriasis-related care outside their zip3.

Figure 2. Patient access to psoriasis-treating providers in urban areas.a

PsO, psoriasis; zip3, 3-digit ZIP code prefix based on the location of the most frequently visited primary healthcare provider during the study period.

aBars indicate the percentage of patients with access to providers in their zip3, by number of available providers. The categories are not mutually exclusive; a patient may have had multiple types of providers in their area. The ‘No PsO-treating subspecialty’ category indicates patients treated by a provider outside their identified zip3.

Figure 3. Patient access to psoriasis-treating providers in rural areas.a

PsO, psoriasis; zip3, 3-digit prefix based on the location of the most frequently visited primary healthcare provider during the study period.

aBars indicate the percentage of patients with access to providers in their zip3, by number of available providers. The categories are not mutually exclusive; a patient may have had multiple types of providers in their area. The ‘No PsO-treating subspecialty’ category indicates patients treated by a provider outside their identified zip3.

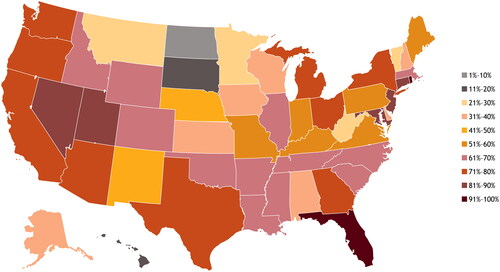

In looking at individual states as a whole, access varied widely and was not concentrated in geographical regions. Rhode Island, Florida, Nevada, Connecticut, and Utah were the 5 states with the highest access to psoriasis-treating providers, whereas Montana, West Virginia, Vermont, Minnesota, South Dakota, Hawaii, and North Dakota were the five states with the lowest access (). In the states with the highest access, 87% to 96% of patients had a psoriasis-treating dermatologist, but in states with the lowest access, fewer than one third of patients had access to a psoriasis-treating provider in their zip3.

Figure 4. Percentage of patients with access to psoriasis-treating dermatologists in their zip3, by state.

Zip3, 3-digit ZIP code prefix based on the location of the most frequently visited primary healthcare provider during the study period.

Regardless of access, a greater proportion of patients with psoriasis in all states received biologics compared with oral therapies, although no more than 17% of patients in any particular state received biologics (). In 28 states―including Hawaii, South Dakota, and Minnesota, which had comparatively low access to psoriasis-treating providers―more than 10% of patients received biologics. The states with the highest proportion of patients receiving biologics were Nevada (16.8%), Connecticut (15.5%), and Delaware (15.4%); those with the lowest proportion were New Mexico (4.3%), Vermont (5.3%), and Wyoming (6.2%). While Nevada and Connecticut were among the states with the highest access to psoriasis-treating providers (89% and 88%, respectively), Delaware was in a relatively low-access tier, with only 31% of patients having access. Vermont was among the states with the lowest access (26%), and New Mexico and Wyoming were in the middle tiers for access (50% and 61%, respectively). Access to psoriasis-treating providers was highest in Rhode Island (96%) and Florida (93%), yet only 11.5% and 8.6% of patients with psoriasis in each of those states, respectively, received treatment with biologics. North Dakota and Hawaii, the 2 states with the lowest access to psoriasis-treating providers at 1% and 11%, respectively, had 7.6% and 11.6%, respectively, receiving treatment with biologics. The proportion of patients receiving oral therapy was low across all states, with only California surpassing 7%. Nine states had fewer than 2% of patients with psoriasis receiving an oral therapy (Alaska, Alabama, Arkansas, Idaho, Iowa, Mississippi, Vermont, Washington, and Wyoming).

Table 2. Access to psoriasis-treating providers and treatment, by state.

Discussion

The findings of this retrospective claims analysis demonstrated clear disparities in psoriasis care across the United States. Notably, patients living in rural areas had limited access to psoriasis-treating providers who prescribe advanced therapies. Up to 75% of patients in rural areas sought care outside their zip3 area compared with only 2% of those living in urban areas. These care-seeking patterns illustrate the limited access to dermatology specialty care in a large portion of the United States, particularly when considering that patients living in rural areas travel greater distances to receive healthcare services compared with urban residents. In urban areas, patients may have sought specialty care outside their zip3 because of health insurance restrictions.

Access to psoriasis-treating providers, or lack thereof, did not necessarily equate to access to advanced therapies. In some cases, access to providers and biologics was consistent, whereas in others, it was conflicting. For example, Nevada and Connecticut were among the states with the highest access to psoriasis-treating providers as well as high proportions of patients with psoriasis receiving biologics, while Vermont had both low access to providers and a low proportion of patients receiving biologics. On the other hand, the 2 states with the highest access to psoriasis-treating providers (Rhode Island and Florida) had relatively low proportions of patients receiving biologics. States with the lowest access to providers were among those with more than 10% of patients with psoriasis receiving biologics, although no state had more than 17% of patients receiving biologics. The percentages of patients receiving oral therapies was consistently low among all states. The observed geographic disparities in access to psoriasis-treating providers and the low proportions of patients receiving advanced therapies raise the question of whether effective psoriasis treatments that are easy to administer (i.e., oral therapies) and require little to no monitoring would help alleviate the burden of limited access to psoriasis treatment in rural areas.

This claims analysis used data from a large database of patients diverse in terms of geographic residence, socioeconomic status, and health insurance types. However, the results should be interpreted in light of several limitations. As with all claims analyses, the data may have been subject to coding errors. Some diagnosis codes may have been included as criteria to rule out psoriasis rather than to confirm the presence of the actual disease. Claims databases also do not capture all factors that may influence outcomes or treatment choices, such as psoriasis severity, nor do they capture the actual distance that patients travel for healthcare; rather than crossing ZIP code demarcations, the number of miles traveled could portray a more accurate description of the burden of rural versus urban residency in seeking healthcare. Pharmacy claims only indicate that a prescription was filled; it is uncertain if patients actually used/took the medication as prescribed. Additionally, claims databases do not capture over-the-counter medication purchases or medications given to patients as samples. The results of this study may have been affected by differences in access to patient support services between patients using oral versus injectable biologics. This analysis was limited to claims for in-person healthcare visits and did not include the use of telemedicine services. Telemedicine has become an increasingly important tool for expanding access to health care and, while it was outside of the scope of the current analysis, it is an area for future research. Finally, this study was limited to patients living in the United States with commercial or government health insurance, and the results may not be generalizable to patients who are uninsured or living in other countries.

In conclusion, access to psoriasis-treating providers varies widely across the United States, with a large proportion of patients living in rural areas seeking care outside of their local area. Regardless of access to providers, utilization of all advanced therapies was low, suggesting the need for effective, easy-to-administer therapy.

Author contributions

Lauren Seigel, Shrushti Shah, Keshia Maughn, Keith Wittstock, and Andrew Alexis contributed to the study design. Shrushti Shah, Keshia Maughn, Miran Foster, Shrushti Shah, and Lakshmi Batchu participated in data acquisition and analysis. All authors had full access to the data and contributed to data interpretation and to the drafting, critical review, and revision of the manuscript, with the support of a medical writer provided by Bristol Myers Squibb. All authors granted approval of the final manuscript for submission.

Patient consent

No consent was required, as this study was a claims analysis using de-identified data. No patients were directly involved.

Acknowledgements

Medical writing assistance was provided by Cheryl Jones of Peloton Advantage, LLC, an OPEN Health company, and funded by Bristol Myers Squibb.

Disclosure statement

Lauren Seigel and Keith Wittstock are employees of and shareholders in Bristol Myers Squibb. Sofia Shoaib, Keshia Maughn, Miran Foster, Shrushti Shah, and Lakshmi Batchu are employees of STATinMED, which has received consulting fees from Bristol Myers Squibb. Andrew Alexis has received grants (funds to institution) from AbbVie, Almirall, Amgen, Arcutis, Bristol Myers Squibb, Cara Therapeutics, Castle Biosciences, Dermavant, Galderma, Leo Pharma, Novartis, Valeant (Bausch Health), and Vyne; served on advisory boards or as a consultant for Allergan/AbbVie, Almirall, Amgen, Arcutis, Beiersdorf, Cara Therapeutics, Castle Biosciences, Cutera, Dermavant, EPI Health (now Novan), Galderma, Incyte, Janssen, Leo Pharma, L’Oreal, Ortho, Pfizer, Sanofi-Regeneron, Swiss American CDMO, UCB, VisualDx, and Vyne; served as a speaker for Bristol Myers Squibb, Regeneron, Pfizer, and Sanofi-Genzyme; and received royalties from Springer, Wiley-Blackwell, and Wolters Kluwer Health.

Data availability statement

The Bristol Myers Squibb policy on data sharing may be found at https://www.bms.com/researchers-and-partners/independent-research/data-sharing-request-process.html

Additional information

Funding

References

- Menter A, Strober BE, Kaplan DH, et al. Joint AAD-NPF guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with biologics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80(4):1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.11.057.

- Armstrong AW, Koning JW, Rowse S, et al. Under-treatment of patients with moderate to severe psoriasis in the United States: analysis of medication usage with health plan data. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2017;7(1):97–109. doi: 10.1007/s13555-016-0153-2.

- Feng H, Berk-Krauss J, Feng PW, et al. Comparison of dermatologist density between urban and rural counties in the United States. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154(11):1265–1271. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.3022.

- Adamson AS, Suarez EA, McDaniel P, et al. Geographic distribution of nonphysician clinicians who independently billed medicare for common dermatologic services in 2014. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154(1):30–36. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.5039.

- Rural-Urban Commuting Area Codes: U.S. Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service; 2023; [25 September 2023]. Available from: https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/rural-urban-commuting-area-codes/.

- Otezla [package insert]. Thousand Oaks, CA: Amgen Inc.; 2021.

- Skyrizi [package insert]. North Chicago, IL, USA: AbbVie Inc.; 2023.

- Cimzia [package insert]. Smyrna, GA: UCB, Inc.; 2019.

- Cosentyx [package insert]. East Hanover, NJ: Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation; 2021.

- Enbrel [package insert]. Thousand Oaks, CA: Immunex Corporation; 2021.

- Humira [package insert]. North Chicago, IL: Abbott Laboratories (AbbVie); 2021.

- Stelara [package insert]. Horsham, PA: Janssen Biotech, Inc.; December 2020.

- Ilumya [package insert]. Cranbury, NJ: Sun Pharmaceutical Industries, Inc.; 2020.

- Tremfya [package insert]. Horsham, PA: Janssen Biotech, Inc.; 2020.

- Taltz [package insert]. Indianapolis, IN: Eli Lilly and Company; 2021.

- Siliq [package insert]. Bridgewater, NJ: Bausch Health US LLC; 2020.

- Remicade [package insert]. Horsham, PA: Janssen Biotech, Inc.; 2021.