Abstract

Purpose: Prurigo nodularis (PN) is a skin disease characterized by intensely itchy skin nodules and is associated with a significant healthcare resource utilization (HCRU). This study aimed to estimate the HCRU of patients in England with PN overall and moderate-to-severe PN (MSPN) in particular.

Methods: This retrospective cohort study used data from the Clinical Practice Research Datalink and Hospital Episode Statistics in England. Patients with Mild PN (MiPN) were matched to patients with MSPN by age and gender for the primary analysis. Patients were enrolled in the study between 1st April 2007 and 1st March 2019. All-cause HCRU was calculated, including primary and secondary care contacts and costs (cost-year 2022).

Results: Of 23,522 identified patients, 8,933 met the inclusion criteria, with a primary matched cohort of 2,479 PN patients. During follow up, the matched cohort’s primary care visits were 21.27 per patient year (PPY) for MSPN group and 11.35 PPY for MiPN group. Any outpatient visits were 10.72 PPY and 4.87 PPY in MSPN and MiPN groups, respectively. Outpatient dermatology visits were 1.96 PPY and 1.14 PPY in MSPN and MiPN groups, respectively.

Conclusion: PN, especially MSPN, has a high HCRU burden in England, highlighting the need for new and improved disease management treatments.

Introduction

Prurigo nodularis (PN), is a skin disease characterized by multiple, intensely itchy skin nodules in symmetrically distributed areas of the extremities, trunk, and head [Citation1–3]. It is a chronic-relapsing, systemic neuroimmune-mediated skin condition and results in substantial physical, mental, emotional, and socio-economic effects on a patient’s quality of life [Citation1–3].

The epidemiology of PN is poorly defined in the UK and Europe, affecting 0.58-11.10 per 10,000 population in European populations [Citation4–6]. PN is estimated to be most common in females and middle-aged adults and disproportionately affects those of African descent. It is associated with several systemic conditions, including human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), chronic kidney disease, and diabetes [Citation3, Citation7, Citation8]. A significant proportion of patients with PN suffer with other atopic-related diseases including atopic eczema/dermatitis, rhinitis/conjunctivitis and asthma [Citation3, Citation5].

Patients with PN experience a range of debilitating symptoms including itch, skin lesions, pain, depression and anxiety [Citation1–3]. All aspects of patients’ lives and mental health are affected, leading to reduced participation in activities, decreased productivity and substantial resource use [Citation1–3, Citation9, Citation10]. Despite this, there are few published studies that examine healthcare resource utilization (HCRU) in patients with PN. A 2020 study conducted by Huang et al. examined the HCRU and costs of patients with prurigo nodularis in the US using a healthcare insurance database [Citation9]. This study concluded that PN incurred higher healthcare visits and costs compared to other inflammatory skin conditions such as atopic dermatitis (AD) and psoriasis [Citation9]. The majority of patients with PN were treated within the dermatology speciality (85·9%) and/or internal/family medicine (69·8%) [Citation9]. The study estimated that patients with PN were more than five times more likely to be treated within the dermatology speciality when compared with AD or psoriasis (p < 0.001) illustrating the high economic burden incurred by patients in both primary and secondary care [Citation9].

Similarly, a 2019 study by Whang et al. examined the inpatient burden of patients with PN in the US [Citation10]. This study showed that hospitalized patients with PN incurred an increased cost of care and length of stay relative to patients without PN. Patients diagnosed with PN had a mean length of hospital stay of 6.51 days vs. 4.62 days, (p < 0.001) and a cost of care $14,772 vs. $11,728, (p < 0.001) compared with patients without PN [Citation10]. These findings further highlight the high healthcare burden and costs incurred by PN patients while hospitalized.

There have been no studies that have assessed the full economic impact of PN in Europe, particularly in England, and explored how costs associated with PN treatment are affected. There is also a lack of understanding about the association of PN with HCRU in the UK, and HCRU associated with differing severities of PN.

Methods

Data source

Patients were selected from the Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD). CPRD is a longitudinal, anonymised research database derived from over 2000 primary-care practices in the UK. CPRD consists of two primary care datasets; CPRD GOLD and CPRD Aurum [Citation11].

Primary-care data in CPRD includes data on demographics, diagnoses, hospital referrals, prescriptions written in primary care, as well as other details of patient care [12]. Roughly 90% of practices in Aurum are presently linked to other data sources, including the Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) dataset and the Office for National Statistics (ONS) mortality dataset [Citation12, Citation13]. Diagnostic information in the CPRD primary-care dataset is recorded using the SNOMED classification and Read codes in Aurum and GOLD, respectively [Citation14].

Patient population

Patients with PN were selected using one or more medical code(s) indicative of PN (Read code M1830 or SNOMED code 63501000) or an ICD-10 (L28.1) recorded in CPRD or linked HES inpatient data respectively.

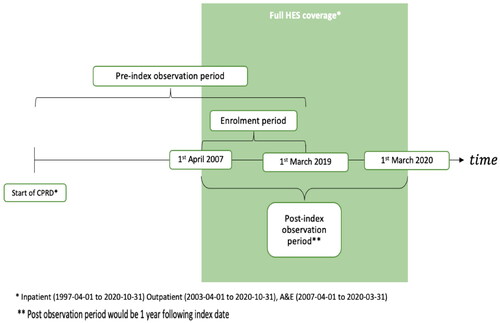

The index date for patients with PN was defined as the patient’s first ever record with a PN diagnosis in either CPRD or HES. The enrollment period for the study started on the 1st April 2007 and finished on the 1st March 2019 ().

Patients that had acceptable research quality data, were eligible if they met the following inclusion criteria:

Their index date fell within the enrollment period.

Had a wash-in period of 180 days (from beginning of patient record to index date).

Had a minimum of one year follow-up

Gender recorded as either male or female.

Aged over 18 years old.

Eligible for HES linkage.

The patient follow-up period spanned the period from the beginning to the end of the patient record defined as the earliest of; transfer out date, death date, last data collection date at practice level, last data collection date under HES linkage HES21 or 01/03/2020.

In addition to the overall PN population, patients with MSPN were matched 1:1 to patients with mild PN (MiPN), matching for age and gender (primary matched cohort).

Patients were classed as having MSPN if they had a record of a prescription for systemic immunosuppressants (methotrexate, ciclosporin, mycophenolate mofetil, lenalidomide, tacrolimus, sirolimus, everolimus, mercaptourine, pimecrolimus, pomalidomide, teriflunomide, cyclophosphamide, long term cortico-steroids and azathioprine) or gabapentinoids following a diagnosis of PN (1). In the absence of other recorded measures of severity in the record, the use of systemic treatments stands as a proxy for moderate to severe disease. Patients with mild PN (MiPN) were defined as any patient with a PN code in either primary or secondary care with no record of a prescription for systemic immunosuppressants or gabapentinoids.

A sensitivity analysis on comorbidity-matched patients was also conducted.

Healthcare resource use (HCRU)

All-cause HCRU, defined as HCRU which occurred during all of follow up and for any reason, not solely for PN, included the following components: primary care visits, all outpatient department visits, outpatient dermatology visits, all inpatient admissions and inpatient dermatology admissions.

Statistical analysis

Baseline characteristics were calculated for the PN cohort and the matched MSPN vs. MiPN cohort. Continuous variables were summarized as mean and standard deviation. Categorical variables were summarized as counts and percentages. Differences between groups were examined using appropriate statistical tests (t-test for continuous data and chi2 for categorical data).

HCRU was calculated for all patients with PN and the matched MSPN vs. MiPN cohort for the entire follow up period. HCRU was also calculated for a subset of patients with at least one visit to outpatient dermatology. Contacts and costs were summarized as rates per patient year. Through use of a generalized linear model (GLM) (adjusted for disease severity, BMI categories, Charlson Comorbidity Index, prior conditions and prior treatments), contacts (Poisson) and costs (Gamma) were modeled using MSPN/MiPN as a variable along with demographic characteristics, prior conditions and prior therapies at index date. An adjusted incidence rate ratio (aIRR) and adjusted cost rate ratio (aCRR) were derived from these models.

Primary care consultations were identified from consultation tables in CPRD and excluded administrative contacts. These were assigned an average cost according to the Unit Cost of Health and Social Care 2022 [Citation15].

Inpatient admissions were identified from the HES inpatient dataset and processed into Healthcare Resource Groups (HRGs) using the HRG-grouper. HRGs were linked to the National Tariff after adjusting for the nature of the admission and the length of stay.

Outpatient appointments were identified from the HES outpatient dataset and costed using specialty codes to designate each appointment to an outpatient tariff, depending on whether the consultation was a first or follow-up visit. Outpatient appointments with no specialty information codes were assigned an average first or follow-up cost.

Results

8,933 patients with PN meeting the inclusion criteria for the study were selected of whom 2,498 patients were classified as moderate-severe. The primary matched cohort contained 2,462 (99%) patients compared to 1,419 (57%) patients in the sensitivity analysis matched cohort.

The mean age of those diagnosed with PN was 61 years old. 57% of all patients with PN were female. A high proportion of patients with PN had prior atopic comorbidities, with higher prevalence in the MSPN group. For example, 39% of all patients with PN had prior AD, with 36% in the MiPN versus 46% in the MSPN cohort (p-value= <0.001). Respective figures for asthma were 33% for patients with PN, 29% of MiPN patients versus 44% of MSPN patients (p < 0.001; and ). A total of 832 (33%) and 367 (15%) patients in the MSPN cohort were treated with gabapentinoids and immunosuppressants, respectively, prior to PN diagnosis.

Table 1. Demographic characteristics in patients with PN and patients with moderate-to-severe PN versus patients with mild PN.

Table 2. Prior conditions in patients with PN and patients with moderate-to-severe PN versus patients with mild PN.

The rate of primary care attendances for patients with PN was 14.27 per patient year (PPY) equating to a cost of £359 PPY. The visit rate for attendances to any outpatient department was 6.68 PPY and incurred a cost of £755 PPY. The rate of visits with a specific coding for outpatient dermatology (OPD) was 1.76 PPY, with an associated cost of £165 PPY (58.54% of patients had a visit to OPD visit during all follow up). In the subset of patients with at least one OPD record (n = 5,229), the rate of visiting was 3.2 PPY, costing £298 PPY while the rate for any outpatient department was 8.89 PPY, costing £979 PPY. All inpatient admissions occurred was 1.07, equating to a cost of £286 PPY ( and ).

Table 3. Healthcare resource use (rate of visits (PPY)) in patients with PN and patients with moderate-to-severe PN versus patients with mild PN.

Table 4. Cost (£PPY) of patients with PN and patients with moderate-to-severe PN versus patients with mild PN.

The primary matched cohort showed the rate of primary care visits during all follow up for the MSPN arm was higher (21.27 PPY) compared to the MiPN arm (11.35 PPY) (p-value < 0.0001). The costs for primary care in the MSPN arm were almost double of those in the MiPN arm (£537 PPY vs. £274 PPY; p-value < 0.0001). Visits and costs to any outpatient department were more than double (10.72 PPY and £1,213 PPY) in the MSPN arm compared to the MiPN arm (4.87 PPY and £563 PPY) (p-value < 0.0001). OPD visits were also higher in the MSPN arm (1.96 PPY) compared to the MiPN arm (1.14 PPY), costing £180 PPY for MSPN and £111 PPY for MiPN (p-value < 0.0001). Similarly, inpatient admissions and costs were higher in the MSPN arm compared to the MiPN arm (1.75 PPY and £382 PPY vs. 0.66 PPY and £192 PPY) (p-value < 0.0001). In the subset of patients with at least one OPD record, the rate of visiting an OPD during all follow up was 3.52 PPY for the MSPN arm and 2.22 PPY for the MiPN arm (p-value < 0.0001), while the costs were £324 PPY and £216 PPY for MSPN and MiPN respectively (p-value = 0.4460). Visits to any outpatient department was 12.85 PPY, costing £1,421 PPY and 6.27 PPY, costing £707 PPY for MSPN and MiPN respectively (p-value < 0.0001). Inpatient admissions and costs were higher in the MPN arm compared to the MiPN arm (1.97 PPY and £383 PPY vs. 0.73 PPY and £194 PPY) (p-value < 0.0001) ( and ).

For the primary matched cohort, after adjusting for MSPN/MiPN along with demographic characteristics, prior conditions and prior therapies at index date, the aIRR for visits was 1.39 for primary care visits, 1.57 for any outpatient visits, 1.16 for outpatient dermatology visits, 1.28 for any inpatient admissions and 2.41 for inpatient dermatology admissions. The aCRR for costs was 1.55 for primary care visits, 1.62 for outpatient visits, 1.63 outpatient dermatology visits, 1.74 for any inpatient admissions and 4.12 for inpatient dermatology admissions ( and ).

The sensitivity analysis for comorbidity-matched patients exhibited the same trends as the primary matched cohort. Primary care visits during all follow up were 19.18 PPY for patients with MSPN and 11.34 PPY for patients with MiPN (p-value < 0.0001). The costs for primary care were also higher in the MSPN arm (£474 PPY vs. £273 PPY) (p-value < 0.0001). OPD visits during all follow up were 1.88 PPY for patients with MSPN and 1 PPY for patients with MiPN, while the costs were £166 PPY and £97 PPY for MSPN and MiPN respectively (p-value < 0.0001). Visits to any outpatient department were 9.15 PPY, costing £1,035 PPY and 4.53 PPY, costing £516 for patients with MSPN and MiPN respectively (p-value < 0.0001). Inpatient admissions and costs were higher in the MPN arm compared to the MiPN arm (0.95 PPY and £326 PPY vs. 0.48 PPY and £179 PPY) (p-value < 0.0001). The rate of OPD visits in the subset of patients with at least one OPD record during all follow up was 3.38 PPY and 1.92 PPY (p-value < 0.0001), costing £299 PPY and £187 PPY (p-value = 0.0037) for patients with MSPN and MiPN respectively. Visits to any outpatient department was 10.89 PPY, costing £1,195 PPY and 5.74 PPY, costing £638 PPY for MSPN and MiPN respectively (p-value < 0.0001). Similarly, inpatient admissions and costs were higher in the MPN arm compared to the MiPN arm (1.03 PPY and 0.52 PPY (p-value < 0.0001) vs. £334 PPY and £172 PPY (p-value = 0.0036)) (Supplementary Tables 1 and 2).

For the sensitivity analysis matched cohort, after adjusting for moderate-severe PN/mild PN along with demographic characteristics, prior conditions, and prior therapies at index date, the aIRR for visits was 1.30 for primary care visits, 1.53 for any outpatient visits, 1.25 for outpatient dermatology visits, 1.59 for any inpatient admissions and 1.37 for inpatient dermatology admissions. The aCRR for costs was 1.51 for primary care visits, 1.65 for outpatient visits, 1.74 outpatient dermatology visits, 1.65 for any inpatient admissions and 1.70 for inpatient dermatology admissions (Supplementary Tables 1 and 2).

Discussion

Despite very few studies examining the epidemiology of PN, the demographic characteristics found for our study population were consistent with the previously published data. Mean age of PN was 61 years [Citation5, Citation8]. Females were disproportionately affected by PN with 57% of all patients with PN being female [Citation5, Citation7, Citation8].

Patients with PN displayed the highest rate of visits in primary care (14.27 PPY) when compared to visits to other departments whereas the highest costs were shown in visits to any outpatient department (£755 PPY). The percentage of patients with PN with visits to any outpatient department were similar compared to OPD visits in a previous US study (93.1% vs. 85.9%), but the percentage of OPD visits were considerably lower when compared to OPD visits in the aforementioned study (58.5% vs. 85.9%) [Citation9]. This may reflect a coding artifact in the UK. In the subset of patients with at least one OPD appointment, the rate of visits and costs were higher, signifying the higher HCRU need in these patients.

A US based study of the HCRU of visits for PN calculated the aIRR was 1.09 for family/internal medicine [Citation9]. This is analogous to primary care within the UK, for which our study found that patients with MSPN had an aIRR of 1.39. Differences between these aIRRs may be explained due the differences in the data source for the studies. In the US, data was from a database containing records of insured patients which may not be comparable to the CPRD which represents universal healthcare provision.

Despite there being no published reports examining HCRU for MSPN, there is published evidence for HCRU in the closely related disease, uncontrolled moderate to severe AD [Citation16]. A published case notes review found that prior to the introduction of a biologic treatment, there were 6.6 visits to dermatology clinics PPY over the observation period [Citation16]. Our study found 1.96 visits PPY to outpatient dermatology and 10.72 visits PPY any outpatient department for the patients with MSPN in the primary matched cohort. Methodological differences exists between the two studies which may explain the. The AD study was based on a patient record review which enrolled patients with confirmed moderate-to-severe AD (based on clinician opinion). The study presented here takes a wider perspective and attempts to capture HCRU for all patients with a coding for PN and a proxy for severity. Therefore, it may be the case that a conservate estimate of the HCRU in MSPN is presented here. Differences between both diseases should be considered when comparing the HCRU.

Previously published data has compared HCRU and costs of patients with PN to those without PN [Citation9, Citation10]. These studies have shown that the HCRU and costs are higher in the PN cohort compared to the cohort without PN [Citation9, Citation10]. Although we did not compare to a population without PN, our study attempts to elucidate the differences in HCRU according to PN disease severity by comparing MSPN to MiPN. This research shows that visits and costs in primary and secondary care were consistently higher in patients with MSPN compared to MiPN. The highest rate of visits was seen in primary care. In the primary matched cohort, primary care visits during all follow up were exceptionally high at 21.27 PPY for patients with MSPN and 11.35 PPY (aIRR = 1.39; p-value <0.0001) for patients with MiPN reflecting the very high burden of disease in primary care. OPD visits during all follow up was 1.96 PPY for patients with MSPN and 1.14 PPY for patients with MiPN (aIRR = 1.16; p-value <0.0001). Likewise, the cost of patients with MSPN was almost double of patients with MiPN (£537 PPY vs. £274 PPY; aCRR = 1.55; p-value < 0.0001). The rate of visits to any outpatient department was higher in the MSPN arm compared to the MiPN arm (10.72 PPY vs. 4.87 PPY; aIRR = 1.57; p-value <0.0001). This trend also extended to the costs (£1,213 PPY vs. £563 PPY; aCRR = 1.62; p-value < 0.0001). This demonstrates the additional HCRU burden of MSPN for the NHS compared to a mild form of the disease. The sensitivity analysis for comorbidity -matched patients showed the same trends as the primary matched cohort whereby the MSPN arm displayed considerably higher HCRU compared to the MiPN arm, although it exhibited slightly lower figures.

The CPRD-HES linkage is the best available data source to examine HCRU at the population level in England. However, the study may have a few limitations. Firstly, it is worth noting that this study may still underestimate the overall HCRU impact of PN, as accurate diagnosis and coding of PN is not yet universally consistent. Furthermore, we have not included patients with a record of other psychotropic medication and psychological interventions in the MSPN population (e.g. selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors) as this fell outside the scope of the study. We recognize that this could be an area for future research. Secondly, the classification of MSPN based on treatment with gabapentinoids and immunosuppressants, although is a pragmatic approach, might have a few constraints. Some of the cases prescribed with immunosuppressants and gabapentinoids in secondary care would not have been captured in the CPRD and hence the most severe PN patients might be underrepresented in this study. On the contrary, gabapentinoids might have also been prescribed for other pain symptoms not related to PN. Hence the results of this study may require further studies to confirm.

Conclusion

This is the first study to examine the HCRU due to PN in England. The findings complement previously published HCRU estimates and contribute the first HCRU estimates for MSPN. Visits to primary and secondary care for patients with PN were shown to be high, primarily made up of primary care attendances, outpatient and OPD visits. PN and even more so, MSPN has a high disease burden in England indicating the need for new and more effective treatments to better manage the disease.

Ethics statement

This manuscript does not contain data from any clinical trial. Dataset utilized is based from the Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD) database. CPRD is a longitudinal, anonymised research database derived from over 2000 primary-care practices in the UK. The CPRD has broad National Research Ethics Service Committee (NRES) ethics approval for purely observational research using the primary care data and established data linkages.

Supplemental Material

Download ()Acknowledgements

Medical writing support was provided by Human Data Sciences and funded by Sanofi and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc. This study is based in part on data from the Clinical Practice Research Datalink obtained under licence from the UK Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. The data is provided by patients and collected by the NHS as part of their care and support. The interpretation and conclusions contained in this study are those of the author/s alone. The RDG number for this study is 21_001632. HES data (Copyright © 2023), re-used with the permission of The Health & Social Care Information Centre. All rights reserved.

Disclosure statement

DB and JT are employees of Sanofi France. RH, OD, RM, and SW are employees of Sanofi UK. OB was an employee of Sanofi UK during the time the study was conducted, and the manuscript was written. EM, BH and EH are employees of Human Data Sciences and received funding from Sanofi. AB is an employee of Barts Health NHS Trust and Queen Mary University and has provided ad hoc consultancy for Sanofi, Abbvie, Almirall, Sanofi, UCB, Lilly, Novartis, Galderma and Leo pharma, Janssen for outside submitted work during the conduct of study.

Data availability statement

The data used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

References

- British Association of Dermatologists. 2022. accessed 28 Oct 2022. Nodular Prurigo. https://www.bad.org.uk/pils/nodular-prurigo/.

- Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center. 2022. accessed 28 Oct 2022. Prurigo Nodularis. https://rarediseases.info.nih.gov/diseases/7480/prurigo-nodularis.

- National Organization for Rare Disorders. 2022. Prurigo Nodularis. rarediseases.org (accessed 28 Oct 2022.

- Ständer S, Ketz M, Kossack N, et al. Epidemiology of Prurigo Nodularis compared with Psoriasis in Germany: A Claims Database Analysis. Acta Derm Venereol. 2020;100(18):1. doi: 10.2340/00015555-3655.

- Morgan C, Thomas M, Ständer S, et al. Epidemiology of prurigo nodularis in England: a retrospective database analysis. Br J Dermatol. 2022;187(2):188–7. doi: 10.1111/bjd.21032.

- Ryczek A, Reich A. Prevalence of Prurigo Nodularis in Poland. Acta Derm Venereol. 2020;100(10):adv00155. doi: 10.2340/00015555-3518.

- Fostini AC, Girolomoni G, Tessari G. Prurigo nodularis: an update on etiopathogenesis and therapy. J Dermatolog Treat. 2013;24(6):458–462. doi: 10.3109/09546634.2013.814759.

- Iking A, Grundmann S, Chatzigeorgakidis E, et al. Prurigo as a symptom of atopic and non-atopic diseases: aetiological survey in a consecutive cohort of 108 patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27(5):550–557. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2012.04481.x.

- Huang AH, Canner JK, Williams KA, et al. Healthcare resource utilization and payer cost analysis of patients with prurigo nodularis. Br J Dermatol. 2020;183(1):182–184. doi: 10.1111/bjd.18925.

- Whang KA, Kang S, Kwatra SG. Inpatient Burden of Prurigo Nodularis in the United States. Medicines (Basel). 2019;6(3):88. doi: 10.3390/medicines6030088.

- Herrett E, Gallagher AM, Bhaskaran K, et al. Data resource profile: clinical practice research datalink (CPRD). Int J Epidemiol. 2015;44(3):827–836. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyv098.

- Hospital Episode Statistics. 2022. Health and Social Care Information Centre. accessed 28 Oct 2022. http://www.hscic.gov.uk/hes.

- Office for National Statistics. 2022. Deaths Registration Data. accessed 28 Oct 2022. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birth sdeathsandmarriages/deaths.

- Benson T. The history of the Read codes: the inaugural James Read memorial lecture 2011. Inform Prim Care. 2011;19(3):173–182. doi: 10.14236/jhi.v19i3.811.

- Curtis L, Burns A. Unit Costs of Health and Social Care 2022. Canterbury: Personal Social Services Research Unit, University of Kent; 2022.

- Hudson RDA, Ameen M, George SM, et al. A real-world data study on the healthcare resource use for uncontrolled moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis in secondary care in the United Kingdom prior to the introduction of biologic treatment. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res. 2022;14:167–177. doi: 10.2147/CEOR.S333847.