Abstract

Purpose: Patients with atopic dermatitis (AD) require both skills and support to effectively manage life with the disease. Here, we developed an agenda-setting tool for consultations with patients with AD to establish a collaborative agenda that enhances patient involvement and prioritizes on self-management support.

Materials and methods: Using the design thinking process, we included 64 end-users (patients and healthcare professionals (HCPs)) across the different phases of design thinking. We identified seven overall categories that patients find important to discuss during consultations, which informed the development of a tool for co-creating a consultation agenda (conversation cards, CCs).

Results: Through iterative user testing of the CCs, patients perceived the cards as both inspiring and an invitation from HCPs to openly discuss their needs during consultations. Healthcare professionals have found the CCs easy to use, despite the disruption to the typical consultation process.

Conclusion: In summary, the CCs provide a first-of-its-kind agenda-setting tool for patients with AD. They offer a simple and practical method to establishing a shared agenda that focuses on the patients’ needs and are applicable within real-world clinical settings.

Introduction

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a chronic skin disease that requires continuous self-management from patients, adapting to fluctuating symptoms, medical treatment, and activities of everyday life (Citation1,Citation2). Furthermore, the impact of AD on patients and their families is considerable, with persistent itching, pain, sleep disturbance, and psychological and social burdens that lead to a diminished quality of life (Citation1,Citation2).

AD is the most prevalent chronic inflammatory skin disease, affecting up to 20% of children and 10% of adults in high-income countries (Citation3,Citation4). Due to its range of signs and symptoms, it is complex to design a universally effective treatment approach (Citation5). Thus, prioritizing optimal patient-centered care is essential from both a well-being and economic perspective (Citation6,Citation7). In the consensus-based European guidelines for treating AD, patient education and the cultivation of self-management skills are baseline recommendations (Citation8). As such, patients often find self-management complex, thus frequently seeking patient-centered professional support (Citation1,Citation9,Citation10). In a qualitative study, patients expressed a desire for guided participation in agenda-setting during consultations, emphasizing their need for self-management support (Citation11).

Incorporating agenda-setting into consultations can enhance self-management by involving patients in decision-making and optimizing consultation time (Citation12–14). By mutually establishing an agenda, patients can actively participate in defining a shared focus for the consultation and receive support in addressing sensitive topics that may otherwise be challenging to discuss (Citation11,Citation12,Citation14). However, for this approach to succeed, co-creating the agenda-setting process with a patient-centered tool for intervention is critical (Citation11,Citation12). The literature includes several studies focused on developing and testing patient-centered tools such as patient-reported outcome measures (PROMS) (Citation15–17), question prompt lists (QPLs) (Citation15,Citation18,Citation19), and conversation cards (CCs) (Citation12,Citation20). Patient-centered tools aim to capture a patient’s perspective on the disease, with agenda-setting serving as a primary or secondary objective. Within the realm of AD, several patient-centered tools exist for both objective and subjective symptom tracking (Citation21) and educational interventions (Citation22). However, we identified only one tool (Citation19) developed to collaboratively establish the consultation framework and address the patient’s specific requirements for self-management support. This particular tool was developed in Japan but did not incorporate user-centered design principles to meet end-users needs. The development of a new tool tailored to Western culture and involving end-users in its creation might increase the benefit to patients with AD.

The aim of this study was to closely collaborate with end-users – patients and healthcare professionals (HCPs) – to develop a patient-centered agenda-setting tool for use in AD consultations and to accomplish initial evaluations of its use in a real-world clinical setting. This resource is intended to co-create the consultation framework starting with patients’ needs for self-management support.

Method

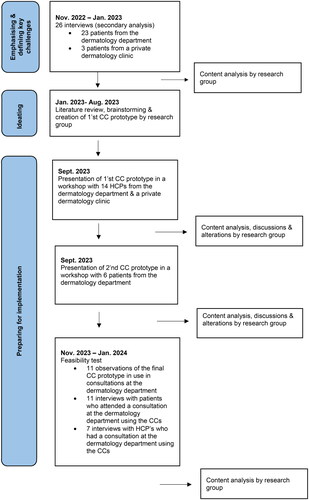

To increase the likelihood of developing an agenda-setting tool that (1) meets the needs of patients with AD, (2) fulfills the requirements of HCPs who provide care for patients with AD, and (3) is applicable in real-world clinical settings, we applied a design thinking approach. Design thinking is a non-linear, iterative method for developing patient-centered interventions that involve emphasizing and defining key challenges (assessing needs), ideating (proposing solutions), and preparing for implementation (iteratively user-testing the prototype in the clinical setting and preparing for forthcoming controlled trial) (Citation23,Citation24). presents a flowchart of the design thinking process, including dates, methods, settings, and number of participants.

Figure 1. Flowchart of the design thinking process, including dates, methods, setting, and participants.

Design thinking

To emphasize and define key challenges and identify the topics that patients deemed essential to address during consultations to support their self-management needs, a secondary data analysis (Citation25) was completed on 26 semi-structured interviews, primarily conducted and analyzed between September 2022 and January 2023, and published in a separate article (Citation11). The secondary analysis was performed using conventional content analysis (Citation25), which involved inductively immersing in the data through careful transcript review and labeling topics that patients described as important for self-management support. These topics were then grouped into broader categories that covered what emerged from the interviews.

For ideating, the literature was reviewed for different agenda-setting tools developed for patients with chronic conditions. The authors brainstormed and discussed insights drawn from patient interviews informing the first phase of the design thinking process and clinical experience to identify the best solution to creating an initial prototype.

To prepare for implementation, workshops with end-users were applied to facilitate a creative space for knowledge sharing and idea generation with the aim of fulfilling end-user expectations to achieve something related to their own interests (Citation26). The workshops had a pre-prepared script (see Table S1a + b) but with the flexibility to follow the lead of patients or HCPs if needed. The agenda-setting tool’s initial prototype was presented in a workshop with HCPs. Following adjustments informed by feedback offered in this workshop, the secondary prototype was presented in a workshop with patients. In both workshops, HCPs and patients were asked for feedback and were encouraged to discuss (1) overall impressions of the prototype, (2) user perception, (3) layout/design, and (4) its usefulness in a consultation setting. The authors facilitated the workshops. Audio recordings were made during both workshops to ensure a comprehensive record of all discussions was captured, while a designated nurse experienced in observation took detailed notes. Workshops were analyzed using conventional content analysis (Citation25) to identify how the initial and secondary prototype was perceived by patients and HCPs. Adjustments from the initial prototype to the secondary version and ultimately to the final prototype were guided by the analysis of workshop feedback and extensive discussions among the authors. Lastly, a feasibility test comprising observations in consultations followed by interviews with HCPs and patients was conducted to evaluate the acceptability and usability of the final prototype in a clinical setting. Observations were applied to capture contextual information, and the interviews were subsequently done to substantiate the observational data and further explore end-users thoughts (Citation27). The first author participated in the consultations as a participating observer (Citation27). The semi-structured observations (Citation27) were guided by an observational guide that focused on (1) how the HCP introduced and used the final prototype, (2) the patient’s initial reaction, (3) the duration of the consultation, and (4) the amount of consultation time explicitly devoted to the agenda-setting tool. Following the consultation, the first author interviewed both the patient and HPC individually. All interviews were guided by an interview guide for respectively patients and HCPs. The patient interviews addressed (1) their overall impression of the agenda-setting tool, (2) user perception, (3) layout/design, and (4) usefulness in consultation. The interviewed HCPs were asked to elaborate on their immediate experience using the final prototype in consultations. Throughout the observations and interviews, notes were taken, and sentences describing thoughts on the final prototype were written down verbatim. The observations and interviews were analyzed using conventional content analysis (Citation25) to identify how the final prototype was used and influenced the clinical practice as well as positive and less positive perceptions of its use.

Inclusion of participants and settings

Participants included in various phases of this study comprised patients with AD and HCPs (physicians, nurses, and nurse assistants).

The patient cohort included individuals of all ages with an AD diagnosis, who spoke and understood Danish, and attended consultations at either a dermatology department or a private dermatological clinic. The patients in all three steps of the design thinking process were selected using purposive sampling (Citation28) to achieve diversity in age, sex, and disease severity. For patients under the age of 15 years, a parent or caregiver participated. To address the complexity of our study aim, we based the number of patients included on an estimated information power (Citation29). We had a specific aim, did not use a specific theory, analyzed across cases, had good quality dialogue, and had a dense specificity as all participants were well experienced with AD consultations. Thus, we aimed for a minimum of 20 patients in the interviews used to inform the ideation phase – see a thorough description of this in a separate article (Citation11). We also aimed to include six patients in the workshops and nine patients in the feasibility test, used to inform the implementation phase. The HCPs were affiliated with a dermatology department or a private dermatological clinic located around a university city. All were experienced in treating and caring for patients with AD. In all three steps of the design thinking process, HCPs were selected through convenience sampling (Citation28), which included all HCPs responsible for managing the overall treatment regimens that support patients with AD. The patients or HCPs were not offered financial compensation for their participation.

The Danish Data Protection Agency approved the study protocol (ID no. P-2022-298). According to Danish law, qualitative studies are not required to be shared with the Regional Committee on Health Research Ethics for approval. All participants received oral and written information on the study before confirming participation and they provided written consent.

Finally, a female patient advisor with eczema, affiliated with a private dermatological clinic commended the study’s findings and the dissemination of the publication.

Results

Emphasizing and defining key challenges

The secondary analysis of the 26 interviews yielded a list of 17 topics that the patients identified as essential to address in consultations to support their self-management. The topics were covered by seven categories: Everyday life with eczema, Medication and treatment plans, Thoughts and feelings, Sexuality and intimacy, Work/study/school, Economy, and Hay fever, asthma, and food allergies.

Ideation

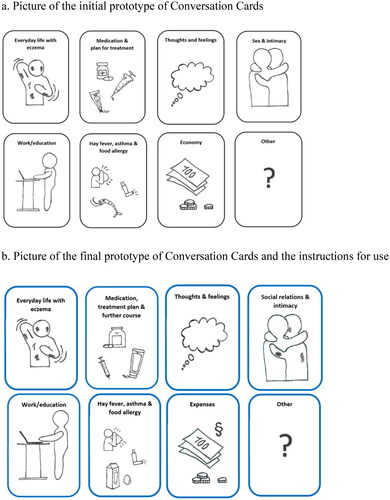

Based on insights drawn from patient interviews, literature review, clinical experience, and discussions between the authors, CCs were considered an appropriate solution for integrating agenda-setting into consultations. We developed the initial CC prototype based on the results (i.e., the seven categories) from the secondary analysis of the interviews with patients with AD. The initial CC prototype consisted of eight pocket-sized cards, each featuring a heading and a hand-drawn illustration (see ). In addition to the cards representing the seven categories identified in the secondary analysis, we included a CC with a question mark to ensure patients always had the opportunity to introduce topics during consultations that they deemed important but were not covered by the predefined CCs. The CCs were developed for use by adults, parents, and young patients.

Figure 2. Pictures of the initial and final prototype of conversation cards. (a) Picture of the initial prototype of conversation cards. (b) Picture of the final prototype of conversation cards and the instructions for use.

Instructions for use

Introduce yourself and welcome the patient;

In random order, introduce the conversation cards to the patient;

Encourage the patient to look at the conversation cards and think about what they would like to discuss in the present consultation;

Initiate a shared agenda setting by listening to the patient’s selection of conversation cards and possibly add one or more conversation cards based on your professional assessment of needs;

If more than one conversation card is chosen, encourage the patient to jointly prioritize the order of the conversation cards included in the consultation;

The HCP can refer to the conversation cards throughout the visit to make it clear to the patient that the conversation cards constitute the agenda of the consultation. However, be aware not to exclude the possibility of new topics that may appear along the way.

Preparing for implementation

User-testing of the CC prototype

The first workshop included 14 participating HCPs, comprising physicians (N = 4), nurses (N = 7), and nurse assistants (N = 3). Among these participants, one physician, one nurse, and three nurse assistants were from the private dermatology clinic; the remaining HCPs were affiliated with the dermatological department. During the workshop, the HCPs provided several minor suggestions for improvement, primarily focusing on refining the comprehensiveness and precision of the headings and illustrations. See Table S2 for a description of each suggestion, along with the rationale and proposed solution. The HCPs emphasized the importance of keeping the number of CCs to a minimum.

The second patient-focused workshop included two adult patients with AD, two young patients with AD, and two parents of children with AD (the mother of one of the children with AD also had AD herself). See for details on each patient’s gender, age, disease severity, treatment, educational level, and employment status. In their feedback, patients reported the CCs as comprehensive and adequately addressing essential aspects of living with AD. They also perceived the CCs as very open and versatile, offering various associations for patients based on their current life situation. The CCs were described as a potential means to gain knowledge and promote more holistic consultations. Patients provided one suggestion for improvement: changing the heading of the CC Intimacy and sex to Social relations and intimacy (see Table S2). Although one patient suggested a card with alternative treatment, most patients, like the HCPs, believed it was essential to keep the number of CCs to a minimum; therefore, this suggestion was not included. Patients also discussed whether notes appearing on the backside of a CC could help. However, one patient participant indicated that this update may lengthen the time spent looking through the CCs and could render the CCs less open for interpretation. Lastly, the patients discussed whether they should receive the CCs prior to consultations to allow more time to select which CCs they wished to discuss. Opinions were divided on this matter, where half of the participants thought it may be easier and less stressful, whereas the other half viewed it as additional homework.

Table 1. Description of patients included in workshops, observations, and interviews.

Following the patient workshop, the final prototype with user instructions was developed (see ). The instructions were based on CCs used in diabetes consultations with minor adjustments (Citation12).

Feasibility test of the final CC prototype

The feasibility test (observations and interviews) was conducted between November 2023 and January 2024. The feasibility test comprised seven HCPs and 11 patients with AD who participated in consultations using the CCs. Descriptions of each patient’s gender, age, disease severity, and selected CCs are available in .

The observations covered eight total consultations, including a physician, nurse, and patient (across four different physicians and one nurse) and three consultations, including a nurse and a patient (across three different nurses). Consultations with a physician and a nurse lasted approximately 11 min (ranging between 8 and 15 min). Consultations with a nurse alone, on average, lasted 27 min (ranging between 25 and 30 min). During consultations with the physician and nurse (together), the patients opted to use between one and three CCs. During consultations with a nurse, the patients opted to use between two and four CCs. The CC Medication, treatment, and further course were selected in all consultations. The HCPs, while using different words to introduce the CCs, followed the instructions to lay them all out and present them as a way to co-create the consultation agenda. The observations revealed that patients generally responded positively and showed interest when presented with the CCs. One patient’s mother exclaimed, ‘Wow, such a good idea’. Another patient said, ‘I know you (spoke to the HCP she had been seeing for many years), so I just speak whatever is on my mind, but I guess the cards might remind me of something’. On average, all patients participating in the observations spent between 30 s and one minute deciding which CCs they wished to discuss. The topics selected by patients using the CCs guided the focus of most of the consultation time in observed sessions.

In the interviews following the observations, the CCs were generally positively perceived. Several patients expressed how the CCs encouraged them to share things they might not have otherwise mentioned. For example, a mother to a two-year-old child said, ‘I don’t think I would have told you that I often wake up at night worrying about my daughter’s eczema if the CC Thoughts and feelings had not been shown’. A 14-year-old female patient said, ‘The CCs worked well because it can sometimes be challenging to figure out what to say or ask about, and the CCs served as examples. We talked about some things that we haven’t discussed before’. This girl’s mother added, ‘It was nice to influence the consultation’. A man aged 67 shared, ‘Normally, the consultation is just like check, check and check, but the CCs made me stop and think about what I needed’. While many were positive, a few patients described the CCs as irrelevant. One patient, a 71-year-old woman, said, ‘It’s amazing to focus the consultation on the patient’s life, and it might be very good for some patients. I would always say what’s on my mind also without CCs. But it’s not a problem to look at them because then you know as a patient that you are welcome to talk about these topics, and I guess that’s nice’. None of the interviewed patients provided feedback on the headings and illustrations. Ten patients found the number of CCs adequate and the categories relevant. However, one patient suggested that fewer CCs might be more manageable to review. None of the patients in the feasibility test thought it was necessary to receive CCs in advance. The reasons for this included: (1) having other tasks to complete in the waiting room, such as questionnaires for databases, etc.; (2) feeling no need to review them in advance; (3) they preferred to review the CCs together with the HCP to share responsibility. Additionally, no patients expressed a desire for the backside of the CCs to be utilized, as it would increase the reading load and decision-making time during consultations.

In the post-observation interviews with HCPs, the CCs were described as easy to use, although naturally integrating them into consultations required some practice. The main concerns raised by HCPs included: (1) using the CCs during consultations with new patients would not be ideal due to the need to gather extensive information and initiate treatment, which typically requires a considerable amount of time; (2) although patients were invited to select the CCs they wished to discuss, HCPs might not have the time to accommodate all preferences within the allotted consultation time; (3) there was a concern about losing control over consultation topics, which could disrupt the sense of comfort and confidence in conducting these consultations. None of the HCPs interviewed offered any comments on the headings and illustrations, and they found the number of CCs adequate and the categories relevant.

Discussion

In this study, we found that CCs can offer a highly adaptable solution for mutual agenda-setting during consultations. Patients perceived the CCs as a positive addition that allowed them to feel included and express themselves more clearly. Nevertheless, integrating CCs into consultations inevitably alters the ‘usual’ approach for HCPs, necessitating some training until comfort and familiarity develop.

The decision to develop CCs, rather than opting for other patient-centered tools (e.g., PROMS and QPL), was driven by the fact that the primary function of CCs is agenda-setting. Furthermore, CCs allow patients to freely interpret a topic while guiding the conversation, do not require technical expertise, and combine text and visual elements, which can enhance health literacy (Citation28). Additionally, insights from the field of diabetes, where CCs have been previously developed and evaluated, were leveraged in this study (Citation12,Citation30).

The seven categories featured in our developed CCs are echoed in studies outlining the framework of various self-management support programs, underscoring their significance for patients with AD worldwide (Citation31–34). As recommended in the national guidelines for AD (Citation35), all patients with AD should receive self-management support. As such, CCs should be part of a broader set of implementation strategies aimed at enhancing self-management support. By aligning the desire for integrated, patient-specific self-management support in routine healthcare (Citation36,Citation37) using CCs and self-management support programs offering more general comprehensive therapeutic patient education and peer-to-peer support (Citation32), there is a greater opportunity to extend support to a broader diversity of patients. This alignment is beneficial to promoting equality in the provision of care.

To address the concerns raised by HCPs regarding the disruption of standard consultations, we recognize that CCs may not be ideal for patients seeing a physician in the clinic for the first time but can be incorporated into subsequent consultations. Additionally, it is important to prioritize the number and order of CCs in mutual agenda-setting. Therefore, both the patient and HCP must be aligned in how to best use consultation time. If there is a need for additional self-management support, studies have indicated that nurse consultations can effectively leverage the competencies and time of various HCPs to benefit patients (Citation11,Citation38,Citation39).

In this study, 14 out of 17 patients reported a preference to view the CCs for the first time during consultations with HCPs. However, patients typically took only about 30 s to select which CCs they wished to discuss in the consultation, indicating that patients may feel compelled to quickly review the CCs to avoid ‘wasting’ time. This inclination may undermine the concept of the CCs facilitating genuine patient involvement in shared agenda-setting and should be further investigated. Another perspective to explore is whether consultations involving CCs significantly differ from those without CCs. Patients in this study assessed the CCs as a way to positively engage in consultations. However, it is unclear whether this sentiment arises simply from being invited to participate in agenda-setting or if CCs offer tailored support from HCPs that would otherwise be lacking. Currently, CCs are undergoing testing in a controlled trial (clinicaltrial.gov NCT06032403) to examine these questions.

Some strengths and limitations of this study are acknowledged. The first author’s role as a participating observer during observations may have affected patients’ willingness to openly share their perspectives on the CCs in post-observation interviews. To minimize the impact of potential biases, the first author encouraged patients to provide detailed descriptions, ensuring that the analysis was grounded in authentic data rather than personal or clinical assumptions (Citation27). Additionally, patients were assured that there were no right or wrong answers, as the interviews aimed to understand how the CCs were perceived. Due to practical constraints, the feasibility test did not include HCPs and patients from the private clinic. Consequently, the study included more patients with moderate to severe eczema compared to those with mild eczema who are typically seen in private clinics. However, the inclusion of 64 participants (43 patients and 21 HCPs) from both the hospital department and the private clinic in various phases of the study renders the CCs relevant within AD care in a local context of the healthcare system. The combination of various qualitative methods and researcher triangulation bolstered the study’s validity (Citation40). Nevertheless, we must exercise caution when generalizing based on a limited number of participants. Although these findings may not be generalizable to all patients with AD, they provide insights into the experiences and descriptions of a subgroup of patients that may align with those at other institutions in Denmark and other parts of the world.

In conclusion, the CCs provide a first-of-its-kind agenda-setting tool for patients with AD. Our findings demonstrate that CCs offer a simple and practical way to establish a shared agenda centered on the patient’s needs and applicable in real-world clinical settings. However, further validation of the CCs requires testing in a larger context.

Author contributions

AK: planning the study design and data collection; collection of data; data analysis and interpretation; manuscript writing. KL: planning the study design and data collection; data analysis and interpretation; manuscript writing; supervision. LS: planning the study design and data collection; data analysis and interpretation; manuscript writing; supervision. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Table 2_supplementary files.docx

Download MS Word (15.9 KB)Table 1_supplementary files.docx

Download MS Word (18.7 KB)Acknowledgements

We thank all patients and healthcare professionals who agreed to participate and openly shared their thoughts on developing a feasible and beneficial agenda-setting tool for optimizing consultations.

Disclosure statement

Anna Krontoft has received funding from Almirall, Sanofi, and The Danish Dermatology Nurse Society and honoraria as a consultant from UCB, Almirall, and Pierre Fabre. Professor Lomborg has received honoraria as a speaker for AbbVie, AstraZeneca, Boehringer-Ingelheim, and Novo Nordisk. Professor Skov has received research funding from Almirall, Sanofi, Novartis, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, the Danish National Psoriasis Foundation, and the LEO Foundation, as well as honoraria as a consultant and/or speaker for AbbVie, Eli Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer, and LEO Pharma, Janssen Cilag, UCB, Almirall, Galderma, Stada, BI, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Sanofi.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Teasdale E, Muller I, Sivyer K, et al. Views and experiences of managing eczema: systematic review and thematic synthesis of qualitative studies. Br J Dermatol. 2021;184(4):1–9. doi: 10.1111/bjd.19299.

- Fasseeh AN, Elezbawy B, Korra N, et al. Burden of atopic dermatitis in adults and adolescents: a systematic literature review. Dermatol Ther. 2022;12(12):2653–2668. doi: 10.1007/s13555-022-00819-6.

- Langan SM, Irvine AD, Weidinger S. Atopic dermatitis. Lancet. 2020;396(10247):345–360. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31286-1.

- Ali F, Vyas J, Finlay AY. Counting the burden: atopic dermatitis and health-related quality of life. Acta Derm Venereol. 2020;100(12):adv00161. doi: 10.2340/00015555-3511.

- Johnson JK, Loiselle AR, Butler L, et al. Action plans for atopic dermatitis: a survey of patient and caregiver attitudes. JAAD Int. 2023;12:184–185. doi: 10.1016/j.jdin.2023.06.011.

- Birkner T, Siegels D, Heinrich L, et al. Itch, sleep loss, depressive symptoms, fatigue, and productivity loss in patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: analyses of TREATgermany Registry Data. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2023;21(10):1157–1168. doi: 10.1111/ddg.15159.

- Augustin M, Misery L, von Kobyletzki L, et al. Unveiling the true costs and societal impacts of moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis in Europe. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2022;36(Suppl. 7):3–16. doi: 10.1111/jdv.18168.

- Wollenberg A, Barbarot S, Bieber T, et al. Consensus-based European guidelines for treatment of atopic eczema (atopic dermatitis) in adults and children: part I. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32(5):657–682. doi: 10.1111/jdv.14891.

- Neale H, Schrandt S, Abbott BM, et al. Defining patient-centered research priorities in pediatric dermatology. Pediatr Dermatol. 2022;40(2):250–257. doi: 10.1111/pde.15199.

- Capozza K, Funk M, Hering M, et al. Patients’ and caregivers’ experiences with atopic dermatitis-related burden, medical care, and treatments in 8 countries. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2023;11(1):264–273.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2022.10.032.

- Krontoft ASB, Skov L, Ammitzboell E, et al. Self-management support for patients with atopic dermatitis: a qualitative interview study. J Patient Exp. 2024;11:23743735241231696. doi: 10.1177/23743735241231696.

- Lomborg K, Munch L, Holmberg Krøner F, et al. “Less is more”: a design thinking approach to the development of the agenda-setting conversation cards for people with type 2 diabetes. Pec Innov. 2022;1:100097. doi: 10.1016/j.pecinn.2022.100097.

- Singh Ospina N, Phillips KA, Rodriguez-Gutierrez R, et al. Eliciting the patient’s agenda – secondary analysis of recorded clinical encounters. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(1):36–40. doi: 10.1007/s11606-018-4540-5.

- Wyld K, Hendrieckx C, Griffin A, et al. Agenda-setting by young adults with type 1 diabetes and associations with emotional well-being/social support: results from an observational study. Intern Med J. 2022;53(8):1347–1355. doi: 10.1111/imj.15919.

- Licqurish SM, Cook OY, Pattuwage LP, et al. Tools to facilitate communication during physician–patient consultations in cancer care: an overview of systematic reviews. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69(6):497–520. doi: 10.3322/caac.21573.

- Pattinson RL, Trialonis-Suthakharan N, Gupta S, et al. Patient-reported outcome measures in dermatology: a systematic review. Acta Derm Venereol. 2021;101(9):adv00559. doi: 10.2340/00015555-3884.

- Makhni EC, Hennekes ME. The use of patient-reported outcome measures in clinical practice and clinical decision making. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2023;31(20):1059–1066. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-23-00040.

- McDarby M, Silverstein HI, Carpenter BD. Effects of a patient question prompt list on question asking and self-efficacy during outpatient palliative care appointments. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2022;65(4):285–295. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2022.12.010.

- Ogawa S, Uchi H, Fukagawa S, et al. Development of atopic dermatitis-specific communication tools: interview form and question and answer brochure. J Dermatol. 2007;34(3):164–171. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2007.00243.x.

- Möller UO, Pranter C, Hagelin CL, et al. Using cards to facilitate conversations about wishes and priorities of patients in palliative care. J Hosp Palliat Nurs. 2020;22(1):33–39. doi: 10.1097/NJH.0000000000000607.

- Leshem YA, Chalmers JR, Apfelbacher C, et al. Measuring atopic eczema control and itch intensity in clinical practice: a consensus statement from the Harmonising Outcome Measures for Eczema in Clinical Practice (HOME-CP) Initiative. JAMA Dermatol. 2022;158(12):1429–1435. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2022.4211.

- Lejay S, Darrigade A-S, Dupre D, et al. Use of therapeutic patient education tools for atopic dermatitis: a French National Survey. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2023;37(11):e1271–e1273. doi: 10.1111/jdv.19244.

- Roberts JP, Fisher TR, Trowbridge MJ, et al. A design thinking framework for healthcare management and innovation. Healthcare. 2016;4(1):11–14. doi: 10.1016/j.hjdsi.2015.12.002.

- Brown T, Wyatt J. Design thinking for social innovation. Stanford Soc Innov Rev. 2009;8(1):31–35.

- Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277–1288. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687.

- Ørngreen R, Levinsen K. Workshops as a research methodology. Electron J e-Learn. 2017;15(1):70–81.

- Weston LE, Krein SL, Harrod M. Using observation to better understand the healthcare context. Qual Res Med Healthc. 2021;5(3):9821. doi: 10.4081/qrmh.2021.9821.

- Campbell S, Greenwood M, Prior S, et al. Purposive sampling: complex or simple? Research case examples. J Res Nurs. 2020;25(8):652–661. doi: 10.1177/1744987120927206.

- Malterud K, Siersma VD, Guassora AD. Sample size in qualitative interview studies: guided by information power. Qual Health Res. 2016;26(13):1753–1760. doi: 10.1177/1049732315617444.

- Munch L, Stensgaard S, Feinberg MB, et al. Evaluating the effect of conversation cards on agenda-setting in annual diabetes status visits: a multi-method study. Patient Educ Couns. 2023;119:108084. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2023.108084.

- Traidl S, Lang C, Schmid-Grendelmeier P, et al. Comprehensive approach: current status on patient education in atopic dermatitis and other allergic diseases. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2022;268:487–500. doi: 10.1007/164_2021_488.

- Wilken B, Zaman M, Asai Y. Patient education in atopic dermatitis: a scoping review. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol. 2023;19(1):89. doi: 10.1186/s13223-023-00844-w.

- Sivyer K, Teasdale E, Greenwell K, et al. Supporting families managing childhood eczema: developing and optimising eczema care online using qualitative research. Br J Gen Pract. 2022;72(719):e378–e389. doi: 10.3399/BJGP.2021.0503.

- Greenwell K, Ghio D, Sivyer K, et al. Eczema care online: development and qualitative optimisation of an online behavioural intervention to support self-management in young people with eczema. BMJ Open. 2022;12(4):e056867. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-056867.

- Wollenberg A, Barbarot S, Bieber T, et al. Consensus-based European guidelines for treatment of atopic eczema (atopic dermatitis) in adults and children: part II. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32(6):850–878. doi: 10.1111/jdv.14888.

- Schulman-Green D, Jaser SS, Park C, et al. A metasynthesis of factors affecting self-management of chronic illness. J Adv Nurs. 2016;72(7):1469–1489. doi: 10.1111/jan.12902.

- Chong AC, Schwartz A, Lang J, et al. Patients’ and caregivers’ preferences for mental health care and support in atopic dermatitis. Dermatitis. 2024;35(S1):S70–S76. doi: 10.1089/derm.2023.0111.

- Brunner C, Theiler M, Znoj H, et al. The characteristics and efficacy of educational nurse-led interventions in the management of children with atopic dermatitis – an integrative review. Patient Educ Couns. 2023;116:107936. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2023.107936.

- Aubert H, Thormann K, Barbarot S, et al. The role of nurses in the management of atopic dermatitis: results of an international survey. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2022;1(2):144–149. doi: 10.1002/jvc2.28.

- Malterud K. Qualitative research: standards, challenges, and guidelines. Lancet. 2001;358(9280):483–488. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)05627-6.