ABSTRACT

Recent scholarship has argued that the concept of highbrow culture is undergoing radical changes, both in content and modes of appropriation. We introduce a new layer to this debate by bringing to the fore the format of the cultural product, distinguishing between “live” cultural products (concerts, exhibitions, live shows) and “recordings” (distributable items such as books or music albums). Using culture sections of newspapers (The Guardian, Le Monde, ABC, El País, Helsingin Sanomat, Dagens Nyheter) from 1960 to 2010 (n = 11,775) we ask what role the format of the cultural product plays for the highbrow/non-highbrow trajectories over time. We show that highbrow coverage faces a relative decline, mostly explained by the expanding non-highbrow arts coverage. Moreover, coverage on live events decreases, while coverage of recordings grows. This trend reflects the highbrow/non-highbrow divide, revealing that the “decline of the highbrow” phenomenon is under closer scrutiny a “decline of the highbrow live event”.

Introduction

Knowledge about and mastery of highbrow arts have traditionally been understood to be important conveyors of power and status in modern Western societies (Bourdieu, Citation1984; Levine, Citation1988). Highbrow arts such as classical music, opera, or ballet have been supported through public funding and institutionalised further through the establishment of codified aesthetic evaluation systems such as prizes and criticisms provided by legitimated experts. The position of highbrow arts is corroborated through their inclusion in formal school curricula that typically reward children from privileged backgrounds already familiar with the material (Bourdieu & Passeron, Citation1979; DiMaggio, Citation1982a; Lareau & Weininger, Citation2003), with teachers recognising these socially inherited and embodied skills as “cultivated naturalness” (Bourdieu, Citation1984, p. 71).

In the past decades, discussions have risen in cultural sociology about whether the status of classical highbrow culture has changed and become less significant as a conveyor of cultural capital and power. The most important debates include cultural omnivorisation, i.e. the process by which eclectic cultural practices replace previously uniquely highbrow practices as markers of high status (Peterson & Kern, Citation1996), and most recently the rise of “emerging forms” of cultural capital in which knowledge and mode of appropriation become significant assets for drawing symbolic boundaries (Prieur & Savage, Citation2011, Citation2013). While there is no consensus regarding these debates, it looks evident that the appreciation of classical highbrow arts is no longer the only indicator of cultural capital.

In this paper, we will adopt a new take on the debate of the “decline of the highbrow” and bring to the fore something which has not been thoroughly handled in previous research and that we have not been able to explore elsewhere at length (Purhonen et al., Citation2019): namely, the role and importance that the format – whether a live product or a distributable recording – of the cultural product has in the complicated highbrow/lowbrow landscape. Tackling the scarcity of longitudinal data sets that would make it possible to observe long-time trends, we use a sample of European quality newspapers’ explicit culture and arts sections between 1960 and 2010 to observe the balance between “highbrow” and “lowbrow” articles in time and assess how this is related to the format of the cultural product treated. Our main research question is: What role does the format of the cultural product play in the trajectories of highbrow and non-highbrow culture across time in quality newspapers?

Why use newspapers to observe these trends? Quality broadsheet newspapers with their special sections devoted to culture and the arts have been considered an excellent source of longitudinal data exposing the public opinions of cultural experts, thus mirroring the cultural hierarchies of different time periods (e.g. Bourdieu, Citation1993; DiMaggio, Nag, & Blei, Citation2013; Janssen, Citation1999; Janssen, Verboord, & Kuipers, Citation2011; Verboord & Janssen, Citation2015). In this paper, in order to assess the long-term trend between the format of the cultural product and its highbrow/non-highbrow status, we use a content analysis of cultural coverage of six European newspapers over a period of fifty years, from 1960 to 2010. Our expectations are that there is indeed a moderate or even a strong decline in the coverage of highbrow arts (H1) between 1960 and 2010 but that there is significant variation across different cultural areas (H2). We expect that the ease of consumption and circulation of a discussed item plays a role: namely, (H3) that the number of newspaper articles covering live cultural products has declined more than the number of articles on recorded products. We hypothesise (H4) that there is a strong link between the highbrow/non-highbrow and live/recording divides, assuming that the expected decline of highbrow arts coverage is linked to the expected decline of live coverage.

Our paper proceeds as follows: We will first discuss the decline of the highbrow thesis and the potential impact of the format of cultural products on their relevance over time. After laying out our research design and the methods employed for the analysis, we will present our empirical results. In the last section, we will reflect on the cultural trend we identify and discuss some areas that need further research.

Between brow and format

We know already that the appreciation and knowledge of classical high arts has been central for maintaining inequalities in Western societies (e.g. Bourdieu, Citation1984; De Graaf, De Graaf, & Kraaykamp, Citation2000; DiMaggio, Citation1982a; DiMaggio & Mukhtar, Citation2004; DiMaggio & Useem, Citation1978; Gans, Citation1974; Ganzeboom, Citation1982; Goffman, Citation1951; Katz-Gerro, Citation2002; Lamont, Citation1992; Purhonen, Gronow, & Rahkonen, Citation2011). However, a large volume of scholarly work has pointed out that “high” and “low” are not universal or unchanging descriptors (Daloz, Citation2010; DiMaggio, Citation1982b; Levine, Citation1988); for instance, the rise of jazz music into the “legitimate” music canon shows well the contextuality and historicity of cultural hierarchies.

Many of the discussions of cultural sociology over the last three decades, however, have revolved around the question of whether the status of classical highbrow arts have changed and, more precisely, declined. The debate on the “meltdown scenario” of highbrow arts (DiMaggio & Mukhtar, Citation2004, p. 192) questions whether the status of highbrow arts is “melting down” because of the replacement of traditional highbrow audiences with younger cohorts that are losing interest in highbrow arts. While DiMaggio and Mukhtar did not find solid evidence to support this thesis, the “greying” of highbrow cultural participation has been reported across national contexts (Bennett et al., Citation2009; Purhonen et al., Citation2011; Roose, Citation2015). Finally, and most recently, many debates on the “emerging forms” of cultural capital have argued that distinctions and hierarchies are increasingly being made within the realm of popular culture (Prieur & Savage, Citation2013).

In addition to these alleged trends, there are various other processes that are intertwined with and play a part in challenging the dominant position of classical highbrow forms. Globalisation impacts the trajectory and pace of cultural flows across borders (Appadurai, Citation1996; Janssen, Kuipers, & Verboord, Citation2008; Tomlinson, Citation1999), making new items and genres spread rapidly and adopt new kinds of legitimisations. The changes taking place in the production and distribution of culture, specifically digitalisation, have introduced novel ways to participate in culture that are radically different from traditional ceremonial ways of consuming highbrow arts such as physically visiting cultural events (Leguina, Arancibia-Carvajal, & Widdop, Citation2017; Wright, Citation2015).

We argue that the format of the cultural product could be one key of understanding better the trajectories of highbrow and non-highbrow arts. Albeit limited in number, some studies on cultural stratification have included the format of consumption in their analysis to explore its association with taste patterns. For instance, Chan and Goldthorpe (Citation2007) found that the majority of music listeners in the UK belong to mass audiences, mainly dependent on the recorded formats of the products. Meanwhile, highly educated omnivore consumers are distinctive in their continuing interest in live musical events. The same study found wide variation across genres (i.e. opera and pop-rock) in terms of the distribution of live versus media (recorded) consumption rates, showing that the supposed decline of highbrow arts might be related to the increase of recorded cultural products – focusing more typically on its more popular forms – and the ease of consumption they offer.

The format of a cultural product is also likely to influence the kinds of consumers or audiences it attracts, and this association can prove relevant in understanding the trajectory of its legitimacy. Previous research suggests that cultural participation correlates more directly with the economic capital and geographical location of the audience than other commonly used indicators such as taste and knowledge (Yaish & Katz-Gerro, Citation2012). Participation involves social action in a certain time and place and usually requires more temporal and financial investment than the domestic, long-term consumption of recorded items. Participating in live events is also bounded by the availability of the cultural items, raising barriers for audiences living outside cultural centres. Barriers are accentuated in live events through feelings of “discomfort with the social conventions of the contexts in which the arts are presented” (DiMaggio & Useem, Citation1978). In fact, recent research has shown marked differences in how insiders and outsiders conceptualise symbolic boundaries (Daenekindt, Citation2019). In this light, we can expect the shift towards portable formats to influence classifications, perhaps by loosening the links between the exclusivity of engagement and the legitimacy granted to a certain cultural product.

Research design

Our data include culture and arts sections from ABC/El País (hereafter ABC/EP) from SpainFootnote1, Dagens Nyheter (DN) from Sweden, Helsingin Sanomat (HS) from Finland, Le Monde (LM) from France and The Guardian (GU) from the UK.Footnote2 All newspapers used as data can be regarded as nationally leading major papers – quality or even “elite” papers, in contrast to tabloids (Verboord & Janssen, Citation2015) – and they share a comparable level of circulation (see Appendix A). Additionally, all tend to be politically moderate, social-democratic, or centre-left (with the exception of the Franco-era ABC). Explored elsewhere in depth (Heikkilä, Lauronen, & Purhonen, Citation2018; Purhonen et al., Citation2019), all newspapers follow roughly similar trends of for instance becoming gradually more international, replacing high arts content with more popular content and becoming more voluminous and visually more appealing. Each newspaper, though, navigates these trends in different speeds: for instance, the Spanish and Swedish newspapers seem to be “early adaptors” regarding the increase of their non-highbrow content, and the Guardian and Le Monde stand out as most focused on domestic issues. The chosen newspapers represent a limited number of centre-left voices, so it would indeed be dubious to assume that they are nationally representative cases. In this paper, because of lack of space, we do not differentiate between newspapers.

The time period studied spans from 1960 to 2010, including six time points (1960, 1970, 1980, 1990, 2000, and 2010). The idea was, first of all, to select a period long enough to make a proper longitudinal observation. Second, we wanted the first time point to cover the moment before the rise and rapid global dissemination of popular and youth culture. And finally, it was essential to be able to scrutinise explicit culture and arts sections; for instance, in 1950, many of the newspapers included in our study still did not have a proper section on culture, but articles with cultural content were sporadically placed among other news (see Heikkilä et al., Citation2018).

In order for the definition of “culture and arts” to stem from the newspapers, we only investigated explicit culture and arts sections. Hypothesising that cultural coverage might be more concentrated towards weekends or holidays and to so eliminate any seasonal variation in the cultural content, we made a systematic random sample of so-called “constructed weeks” (Janssen et al., Citation2008; Riffe, Aust, & Lacy, Citation1993). Thus we first divided each year into thirds (January-April, May-August, September-December) and then used a stratified sampling procedure to select random dates to comprise one full week for each of them. There were thus three “constructed weeks” for each full year and each newspaper. This totals to 585 daily newspaper editions, for which we collected only explicit culture and arts sections and specific similarly themed supplements (that appear mostly from 1990 onwards, see Heikkilä et al., Citation2018). The unit of our analysis is an individual article, resulting in 11,775 cases that we then coded using a coding system that consisted of forty-nine variables touching upon both the details (e.g. location on the page, illustration, writer's gender) and content (e.g. primary cultural area, country of origin of the artist) of the articles, some dichotomous (for instance, “Aesthetic dimension”, i.e. whether the article makes explicit judgements on the aesthetic value of the cultural products discussed in the article), but some with more than twenty categories (for instance, “Primary cultural area”, with 21 options). The data were collected in years 2013–2014 and coded by a team of 11 coders between 2014 and 2015. Intercoder reliability tests were conducted; the reliability expectedly varied somewhat between coders, but all variables used met a satisfactory level of reliability (Krippendorff, Citation2004). The characteristics of the data and the coding process have been described more in detail elsewhere (Purhonen et al., Citation2019).

Our key variable is the primary cultural area, which originally included 21 categories ranging from the most established arts (e.g. music, literature) and other classical highbrow arts (e.g. opera, theatre, or fine arts) to more popular and modern areas of culture (e.g. film, television, photography, and comics) and cultural areas other than conventional art forms (e.g. cultural policy). Sensitive to the arguments about an oscillating sphere of what is considered “highbrow” in the first place, regarding the analyses of this paper we decided to operationalise highbrow and non-highbrow cultural areas through a conventional classification used, for instance, by Janssen et al. (Citation2011). To do this, we recoded our primary cultural area variables into either “highbrow arts” or “non-highbrow arts”. Into “highbrow arts”, we included architecture, ballet and modern dance, classical music (including opera), literary fiction, theatre, and visual arts as well as the following subgenres: ballet and modern dance; classical music; novels, poetry, plays, and “other nonfiction”. All other primary cultural areas and subgenres were operationalised as “non-highbrow”, again according to the categories used by Janssen et al. (Citation2011).

Our second important variable is the format of the cultural product. The original coding book referred to “the physical form of the piece of art treated in the article”, resulting in a dichotomy between live (real-time cultural events like concerts, plays, or exhibitions) and recordings (recorded or distributable cultural products such as music albums, DVDs, films, books, or magazines). If the article did not make any reference to any cultural product (such as, for instance, articles on cultural policy or columns), the format of the cultural product was not coded. This decreased the number of cases under analysis to 6823.

In addition to the format of the cultural product, the main independent variable in the paper is the time point (1960, 1970, 1980, 1990, 2000, 2010), as we are tracking trends over this time span. Besides presenting descriptive analyses in the form of tables and figures about the trend in highbrow coverage and the role of the format of the cultural product in that trend, we employ binary logistic regression modelling to examine the trend in highbrow coverage more precisely. Most importantly, logistic regression allows us to formally test the magnitude and statistical significance of the interaction effect between the decade and the format of the cultural product on the prevalence of highbrow arts (versus non-highbrow arts) as the main topic of the articles. In other words, this analysis reveals whether the trend in highbrow coverage is similar between the live and recording-based cultural products. In the logistic regression, the time point is used as a continuous – rather than categorical – variable (1960 = 0, 1970 = 1, and so on). The odds ratio of the time point variable (decade) thus shows to what extent the dependent variable (highbrow coverage) has changed between our original sample intervals. After running the logistic models in several different ways, we concluded that using the time point as a categorical variable gave mostly identical findings but produced too many interaction terms to be efficiently reported in a limited space. Finally, employing logistic regression also gives us the possibility to control for other potentially important characteristics of the newspapers included in the data when examining the trend of highbrow coverage and the above-mentioned interaction effect. Thus, the newspaper itself, the number of cultural pages, the size of the article, and the type of the article were included in the models as control variables. The categories and distributions of all independent variables are presented in Appendix B.

Results

We will start by examining the basic proportions of articles on all cultural fields defined as highbrow arts according to year, as seen in . Cultural areas that do not fall into the highbrow categories are clustered together as “non-highbrow”. We can see that, taken together, the share of non-highbrow art coverage slowly increases at the cost of highbrow coverage. While in 1960 highbrow coverage still dominates, by 1970 there is more coverage of non-highbrow arts, and in 2010 only one-third of all articles cover highbrow arts. Naturally, this general trend hides many significant differences across them. Theatre shows the clearest trend in terms of coverage: Overall, it is a large area in terms of coverage, and in 1960 and 1970, it is the most covered area. After 1970, theatre coverage faces a dramatic decrease (from more than 20% to less than 5%). Visual arts show only a slightly decreasing trend. Classical music, including opera, is the most covered of the highbrow arts, and it faces a small yet pertinent decline after 1990.Footnote3 Meanwhile, literature, a substantial category in terms of the volume of coverage during the entire time span, has no clear trend. Architecture and dance have been extremely small areas in terms of coverage during the entire time period.

Table 1. The proportion of articles on different highbrow arts according to year (percentages).

explores the proportion of articles on live and recording formats of the cultural products discussed according to the year. The table shows that the balance between articles on live events and recordings did indeed turn upside down between 1960 and 2010. While in the sixties the large majority of coverage focuses on live cultural products, in 2010 they count for less than a third of all articles. It is worth keeping in mind that the general growth of the absolute number of newspaper articles is so strong that the radical decline of the live format remains a relative decline: In 1960 and 2010, there are roughly the same number of articles on live events (N = 454 and 474, respectively), whereas the absolute number of articles on recordings grows strongly between 1960 and 2010 (N = 278 and 968, respectively).

Table 2. The proportion of articles on “live” and “recording” formats of the cultural products discussed according to year (percentages).

scrutinises the relationship between the highbrow/non-highbrow and live/recording divides, using a logistic regression to predict the proportion of highbrow arts articles by the main effects of the year and the format of the cultural product (Model 1), as well by the interaction effect between the year and the format of the cultural product (Model 2).

Table 3. Articles on highbrow arts according to year, the format of the cultural product discussed in the articles, and their interaction effect. Odds ratios (with 95% confidence intervals in brackets) and Wald statistics from logistic regression analysis.

shows a very strong association between the format of the cultural product and the proportion of the articles on highbrow arts. The main finding is that the percentage of live event coverage that addresses highbrow forms, such as articles on classical music concerts or art exhibitions, has decreased much more dramatically than that of recordings. Even if the downward-going trend over time is substantial, the size of the main effect of the format of the cultural product is about eight times larger than the main effect of the year, when both (as well as the control variables) are taken into consideration (reflected in the respective Wald values, Model 1). Thus, articles on high art cover approximately four times more live cultural products than distributable recordings. Furthermore, also importantly shows that there is a statistically very significant (p < 0.001) interaction effect between the time point and the format of the cultural product. This means that the main effects of decade and the format of the cultural product have to be specified: the declining trends in highbrow arts coverage differ substantially between articles discussing live highbrow events and articles on highbrow recordings. More precisely, the interaction shows that the decline has been more dramatic in the case of live event coverage than in the coverage of recordings.

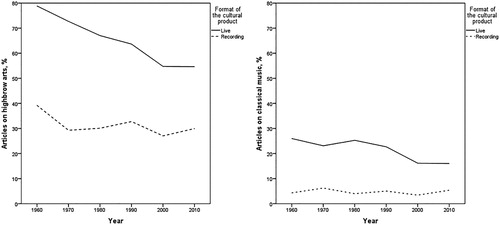

To illustrate the importance of the format of the cultural product (reflected in the statistically significant interaction shown in Model 2 of ), presents how the trends in the proportions of articles on highbrow arts are divided according to whether the format of cultural product discussed in the article is live or recording. We illustrate this by examining first all highbrow arts (the left-hand side of ) and then one art form alone, in this case classical music (the right-hand side of ), to show that the same phenomenon is seen at both the general and field-specific levels. The general trend shown on the left side of is of course partly due to the declining theatre coverage and the stable or increasing coverage of literary fiction: Theatre is almost solely live, and literary fiction is a recording format. What is important, however, is that the same trend holds in the case of music alone. The proportion of the coverage of live music events decreases more clearly than the proportion of the coverage of different music recordings.

Figure 1. The proportion of articles on all highbrow arts (left) and classical music (right) according to year and the format of the cultural product discussed in the articles (percentages).

Finally, we wanted to shed more light on our last hypothesis, which proposed that the expected decline of highbrow arts coverage would be linked to the hypothesised decline of live coverage. shows that the trend and the significance of the format of the cultural product is radically different for articles covering highbrow and non-highbrow arts. While in the realm of recorded products the proportions of highbrow and non-highbrow areas change only slightly between 1960 and 2010 in live coverage (from 39% / 61% to 30% / 70%), their proportions in general face a dramatic change – from 79% / 21% in 1960 to 55% / 45% in 2010 – meaning that out of the live coverage of all cultural areas, almost half cover non-highbrow areas in 2010. The “decline of the highbrow” seems thus to be a phenomenon strongly and intrinsically linked to the “decline of the live event”, the mirror image of the “rise of the commercially distributed cultural product”.

Table 4. The proportion of highbrow and non-highbrow articles in the newspaper data according to year; articles on “live” and “recording” formats of the cultural products discussed separately (percentages).

Discussion and conclusion

In this paper, we have tried to understand better the role of the format of a cultural product in determining its cultural status and to contribute to the “decline of the highbrow” argument by showcasing it from the point of view of the hierarchies constructed in one long-standing cultural institution. Using as a longitudinal data set culture and arts sections of quality European newspapers between 1960 and 2010, we have shown that instead of a general decline in the visibility of highbrow arts, what we see is a decline in the prominence of highbrow live events.

Drawing on the discussions in the scholarly literature on the different forms of the diminishing role of the status of traditional highbrow arts we expected that (H1) there would be a decline in the quality newspapers’ coverage of highbrow arts. Our analysis supported this, showing that, indeed, the share of articles on traditional highbrow arts declines between 1960 and 2010 – a decline which is partly explained by the fact that, while the volumes of highbrow arts coverage remain largely stable, the volumes of non-highbrow arts coverage grow exponentially between 1960 and 2010.

This rather black-and-white finding takes on more shades when explored more in depth: In line with our second hypothesis (H2), we observed significant internal variations across the journalistic attention shown to different highbrow arts. For instance, literary fiction coverage faces no decline; on the contrary, it grows, whereas theatre coverage is in a consistent decline. As evidenced by Janssen et al.'s study (Citation2011), these trends have wider resonance in other European countries, as well as in America. Observed field by field, there is a strong relative decline only in articles on theatre and classical music. This finding reflects well the recent research on cultural participation, which shows that while participation in popular culture has grown dramatically since the 1960s and become a relevant field for new kinds of cultural distinctions (Prieur & Savage, Citation2011, Citation2013), highbrow participation has remained highly stable (Daenekindt & Roose, Citation2015; Donnat, Citation2011; Kolb, Citation2001).

Returning to our aim to bring to the fore the format of the cultural products covered, differences across arts were largely in line with our expectation (H3), in that the number of newspaper articles covering live cultural products faced a stronger decline than the number of articles on recorded products. Here, we saw that the coverage of recorded highbrow cultural products faced a much less pertinent decline (if any decline at all) than the coverage of live highbrow cultural products such as theatre or classical music concerts. This is a novel finding, as previous literature paid hardly any attention to how highbrow art's format affects media visibility, and thus potentially its status and audience appreciation, as well (however, see Janssen et al., Citation2008; Leguina et al., Citation2017). This certainly directs us to ask further questions about whether or not the decline of the live event can be read in line with the supposed trend towards democratisation or instead as a path that opens new axes of differentiation and “entry problems” (DiMaggio & Useem, Citation1978) in the context of rising digitalisation. It should be emphasised that the dramatic decline of the live highbrow coverage we have traced remains a relative decline vis-à-vis the exponentially growing coverage of recordings; it does not disappear but rather stagnates and loses relative volume in the landscape of other increasing types of coverage.

Finally, we hypothesised (H4) that the highbrow/non-highbrow separation would be linked to the live/recording division: We saw that the strong decline of live coverage mostly affected highbrow arts coverage, which was further corroborated by the fact that the live coverage of non-highbrow areas increased. The highbrow/non-highbrow divide seems thus fundamentally linked to the format of the cultural product, making the only object in real decline the highbrow live performance, a finding which would fit the assumption of shrinking and greying highbrow audiences (DiMaggio & Mukhtar, Citation2004). It is these same profiles that probably most overlap with the intended readership of the rather conventional newspapers we have studied.

The main limitations of our study include that our data cover only the concrete outcome of the multiple, complex and overlapping selection, evaluation and gatekeeping processes that take place behind the scenes of quality newspapers – an at least to some extent slow-paced information outlet in the era of rapidly updated broadcast and social media. This paper is not able to tackle the questions of how newspapers’ culture and arts sections are constructed, what kind of steps take place in the selection procedures regarding the published materials and how, in general, are negotiations taking place in newsrooms and beyond (cf. Hellman & Jaakkola, Citation2012; Nørgaard Kristensen & From, Citation2018). Also, we are indeed not able to draw conclusions about how and whether the readers of these newspapers are affected by what is in the culture and arts sections and whether it alters their cultural consumption. Thus, historical studies on cultural intermediation focusing changes in cultural hierarchies like ours should ideally be combined with information from other studies also interested in cultural changes but focusing on data sources (such as sales lists, music charts etc.) that are more directly indicative of actual consumption trends (e.g. Achterberg, Heilbron, Houtman, & Aupers, Citation2011). And finally, due to the nature of our empirical research object, European quality newspapers, we have only touched on the coverage on the most traditional, well-known formats of cultural products, live and recording, thus positioning ourselves outside of the enormous and increasingly prominent culture that exists only online (cf. Wikström, Citation2009). Taking these paths remains task for future research.

Notes on contributors

Riie Heikkilä is a postdoctoral researcher at the Faculty of Social Sciences at Tampere University, Finland. Her main research interests include cultural capital, cultural consumption, and social stratification, and comparative sociology in general.

Irmak Karademir Hazır is Senior Lecturer in Sociology at the Department of Social Sciences, Oxford Brookes University, UK. Her research focuses on the lived experience of social class, inequality, embodiment, cultural classifications, and socio-cultural change.

Semi Purhonen is Professor of Sociology at the Faculty of Social Sciences, Tampere University, Finland. Between 2013 and 2018, he worked as an academy research fellow at the Academy of Finland and was the director of the research project Cultural Distinctions, Generations, and Change, which lay the ground for the present article. His research interests are in the fields of cultural sociology, consumption, lifestyles and social stratification, sociology of age, generations and social change, and comparative research and sociological theory.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 For Spain, two newspapers were used because El País, the logical equivalent of the other newspapers analysed, was not founded until 1976. ABC is used as a replacement for the two first decades of the time period studied.

2 The data gathered for this project originally included Turkish newspaper Milliyet (for a more detailed description, see Purhonen et al., Citation2019). However, the research questions posed in this paper are not relevant in the case of Milliyet since established highbrow Western arts have not enjoyed the same status in Turkey as in the other countries included in the analysis (Belge, Citation1996).

3 The declining trajectory of classical music is much more dramatic if calculated from all articles on music and thus inspected as a relative shift between musical genres. We analyse the trends of pop-rock and classical music coverage in detail elsewhere (Fernández Rodríguez, Heikkilä, & Purhonen, Citation2018; Purhonen, Heikkilä, & Karademir Hazır, Citation2017; Purhonen et al., Citation2019).

References

- Achterberg, P., Heilbron, J., Houtman, D., & Aupers, S. (2011). A cultural globalization of popular music? American, Dutch, French, and German popular music charts (1965 to 2006). American Behavioral Scientist, 55(5), 589–608. doi: 10.1177/0002764211398081

- Appadurai, A. (1996). Modernity at Large: Cultural Dimensions of Globalization. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Belge, M. (1996). Kültür: Cumhuriyet dönemi Türkiye ansiklopedisi. [Culture: Encyclopedia of the Republican era of Turkey]. İletişim Yayınları, 5, 1287–1304.

- Bennett, T., Savage, M., Silva, E., Warde, A., Gayo-Cal, M., & Wright, D. (2009). Culture, Class, Distinction. London: Routledge.

- Bourdieu, P. (1984). Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Bourdieu, P. (1993). The Field of Cultural Production: Essays on art and Literature. Cambridge, UK: Polity.

- Bourdieu, P., & Passeron, J.-C. (1979). The Inheritors: French Students and Their Relation to Culture. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Chan, T. W., & Goldthorpe, J. H. (2007). Social stratification and cultural consumption: Music in England. European Sociological Review, 23, 1–19. doi: 10.1093/esr/jcl016

- Daenekindt, S. (2019). Out of tune. How people understand social exclusion at concerts. Poetics. Advance online publication. doi:10.1016/j.poetic.2018.12.002

- Daenekindt, S., & Roose, H. (2015). De-institutionalization of high culture? Realized curricula in secondary education in Flanders, 1930–2000. Cultural Sociology, 9, 515–533. doi: 10.1177/1749975515576942

- Daloz, J.-P. (2010). The Sociology of Elite Distinction: From Theoretical to Comparative Perspectives. Basingstoke: Palgrave MacMillan.

- Davara Torrego, F. J. (2005). Los periódicos españoles en el tardo franquismo: Consecuencias de la nueva ley de prensa. Revista Comunicación y Hombre, 1, 131–147. doi: 10.32466/eufv-cyh.2005.1.69.131-147

- De Graaf, N. D., De Graaf, P. M., & Kraaykamp, G. (2000). Parental cultural capital and educational attainment in the Netherlands: A refinement of the cultural capital perspective. Sociology of Education, 73, 92–111. doi: 10.2307/2673239

- DiMaggio, P. (1982a). Cultural capital and school success: The impact of status group participation on the grades of U.S. high school students. American Sociological Review, 47, 189–201. doi: 10.2307/2094962

- DiMaggio, P. (1982b). Cultural entrepreneurship in nineteenth-century Boston: The creation of an organizational base for high culture in America. Media, Culture & Society, 4, 33–50. doi: 10.1177/016344378200400104

- DiMaggio, P., & Mukhtar, T. (2004). Arts participation as cultural capital in the United States, 1982–2002: Signs of decline? Poetics, 32, 169–194. doi: 10.1016/j.poetic.2004.02.005

- DiMaggio, P., Nag, M., & Blei, D. (2013). Exploiting affinities between topic modeling and the sociological perspective on culture: Application to newspaper coverage of U.S. government arts funding. Poetics, 41, 570–606. doi: 10.1016/j.poetic.2013.08.004

- DiMaggio, P., & Useem, M. (1978). Social class and arts consumption. Theory and Society, 5, 141–161. doi: 10.1007/BF01702159

- Donnat, O. (2011). Pratiques culturelles, 1973–2008: Dynamiques générationnelles et pesanteurs sociales. Culture Études, 7, 1–36. doi: 10.3917/cule.117.0001

- Fernández Rodríguez, C. J., Heikkilä, R., & Purhonen, S. (2018). ¿Hacia una mayor apertura cultural? Un análisis de la cobertura de artículos sobre música en la prensa de referencia de cinco países europeos (1960–2010). Revista Internacional de Sociología, 76, e092.

- Gans, H. J. (1974). Popular Culture and High Culture: An Analysis and Evaluation of Taste. New York: Basic Books.

- Ganzeboom, H. (1982). Explaining differential participation in high-cultural activities: A confrontation of information-processing and status-seeking theories. In W. Raub (Ed.), Theoretical Models and Empirical Analyses (pp. 186–205). Utrecht: E.S. Publications.

- Goffman, E. (1951). Symbols of class status. The British Journal of Sociology, 2, 294–304. doi: 10.2307/588083

- Gustafsson, K. E., & Rydén, P. (2010). A History of the Press in Sweden. Gothenburg: Nordicom.

- Heikkilä, R., Lauronen, T., & Purhonen, S. (2018). The crisis of cultural journalism revisited: The space and place of culture in quality European newspapers from 1960 to 2010. European Journal of Cultural Studies, 6, 669–686.

- Hellman, H., & Jaakkola, M. (2012). From aesthetes to reporters: The paradigm shift in arts journalism in Finland. Journalism: Theory, Practice and Criticism, 13, 783–801. doi: 10.1177/1464884911431382

- IFABC. (2013). National Newspapers Total Circulation 2011 by International Federation of Audit Bureaux of Circulations. Retrieved from http://www.ifabc.org/site/assets/media/National-Newspapers_total-circulation_IFABC_17-01-13.xls

- Janssen, S. (1999). Art journalism and cultural change: The coverage of the arts in Dutch newspapers 1965–1990. Poetics, 26, 329–348. doi: 10.1016/S0304-422X(99)00012-1

- Janssen, S., Kuipers, G., & Verboord, M. (2008). Cultural globalization and arts journalism: The international orientation of arts and culture coverage in Dutch, French, German, and the U.S. newspapers, 1955 to 2005. American Sociological Review, 73, 719–740. doi: 10.1177/000312240807300502

- Janssen, S., Verboord, M., & Kuipers, G. (2011). Comparing cultural classification: High and popular arts in European and U.S. elite newspapers. Kölner Zeitschrift für Soziologie und Sozialpsychologie, 63, 139–168.

- Katz-Gerro, T. (2002). Highbrow cultural consumption and class distinction in Italy, Israel, West Germany, Sweden, and the United States. Social Forces, 81, 207–229. doi: 10.1353/sof.2002.0050

- Kelly, M., Mazzoleni, G. and McQuail, D. (Eds.). (2014). The Media in Europe: The Euromedia Handbook. London: Sage.

- Kolb, B. M. (2001). The effect of generational change on classical music concert attendance and orchestras’ responses in the UK and US. Cultural Trends, 11, 1–35. doi: 10.1080/09548960109365147

- Krippendorff, K. (2004). Content Analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Lamont, M. (1992). Money, Morals, and Manners: The Culture of the French and the American Upper-Middle Class. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Lareau, A., & Weininger, E. B. (2003). Cultural capital in educational research: A critical assessment. Theory and Society, 32, 567–606. doi: 10.1023/B:RYSO.0000004951.04408.b0

- Leguina, A., Arancibia-Carvajal, S., & Widdop, P. (2017). Musical preferences and technologies: Contemporary material and symbolic distinctions criticized. Journal of Consumer Culture, 17(2), 242–264. doi: 10.1177/1469540515586870

- Levine, L. W. (1988). Highbrow/Lowbrow: The Emergency of Cultural Hierarchy in America. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Nørgaard Kristensen, N., & From, U. (2018). Cultural journalists on social media. MedieKultur: Journal of Media and Communication Research, 34, 76–97. doi: 10.7146/mediekultur.v34i65.104488

- Peterson, R. A., & Kern, R. M. (1996). Changing highbrow taste: From snob to omnivore. American Sociological Review, 61, 900–907. doi: 10.2307/2096460

- Prieur, A., & Savage, M. (2011). Updating cultural capital theory: A discussion based on studies in Denmark and in Britain. Poetics, 39, 566–580. doi: 10.1016/j.poetic.2011.09.002

- Prieur, A., & Savage, M. (2013). Emerging forms of cultural capital. European Societies, 15, 246–267. doi: 10.1080/14616696.2012.748930

- Purhonen, S., Gronow, J., & Rahkonen, K. (2011). Highbrow culture in Finland: Knowledge, taste and participation. Acta Sociologica, 54, 385–402.

- Purhonen, S., Heikkilä, R., & Karademir Hazır, I. (2017). The grand opening? The transformation of the content of culture sections in European newspapers, 1960–2010. Poetics, 62, 29–42.

- Purhonen, S., Heikkilä, R., Karademir Hazır, I., Lauronen, T., Fernández Rodríguez, C. J., & Gronow, J. (2019). Enter Culture, Exit Arts? The Transformation of Cultural Hierarchies in European Newspaper Culture Sections, 1960–2010. London and New York: Routledge.

- Riffe, D., Aust, C. F., & Lacy, S. R. (1993). The effectiveness of random, consecutive day and constructed week samples in newspaper content analysis. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 70, 133–139.

- Roose, H. (2015). Signs of ‘emerging’ cultural capital? Analysing symbolic struggles using class specific analysis. Sociology, 49, 556–573. doi: 10.1177/0038038514544492

- Taylor, G. (1993). Changing Faces: A History of the Guardian 1956–1988. London: Fourth Estate.

- Tomlinson, J. (1999). Globalization and Culture. Cambridge, UK: Polity.

- Tommila, P., Ekman-Salokangas, U., Aalto, E-L., & Salokangas, R. ( Eds.). (1988). Suomen lehdistön historia 5: Hakuteos Aamulehti–Kotka Nyheter. Sanoma- ja paikallislehdistö 1771–1985. [History of the Finnish press 5: Reference work Aamulehti–Kotka Nyheter]. Kuopio: Kustannuskiila.

- Verboord, M., & Janssen, S. (2015). Arts journalism and its packaging in France, Germany, The Netherlands and The United States, 1955–2005. Journalism Practice, 9, 829–852. doi: 10.1080/17512786.2015.1051369

- Wikström, P. (2009). The Music Industry: Music in the Cloud. Cambridge, UK: Polity.

- Wright, D. (2015). Understanding Cultural Taste: Sensation, Skill and Sensibility. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Yaish, M., & Katz-Gerro, T. (2012). Disentangling 'cultural capital': The consequences of cultural and economic resources for taste and participation. European Sociological Review, 28, 169–185. doi: 10.1093/esr/jcq056