ABSTRACT

This paper explores the interface between the state, the cultural industries and the financial market by focusing on a policy experiment from South Korea: using venture capital for public cultural investment. This policy experiment has significantly increased capital injection to the cultural industries and has provided a fertile ground for the industries to quickly grow. Challenging the dichotomist understanding of the state-market relations, this paper views the government’s use of venture capital as a “state-led regulated financialisation” project, in which the cultural ministry has created, expanded and “tamed” the cultural venture capital market. Venture capital companies' profit maximisation is seriously limited by not only government regulations but also strategic behaviour of private investors (cultural distributors). Yet, the paper points out that involving the financial market further complicates cultural industry policy, which already entails tension between culture and industry.

Introduction

Using finance is an important part of cultural industry policy. The examples include loans (Creative England’s debt financing),Footnote1 loan guarantees for banks who lend money to cultural businesses (France’s IFCIC, Creative Europe’s loan guarantee facility, South Korea’s completion guarantee, and the UK’s Creative Industries Finance, 2012–2017) and incentives for private investors (France’s SOFICA scheme and the UK’s Enterprise Investment Scheme) (EAO, Citation2014; Jäkel, Citation2003; Morawetz et al., Citation2007; Walkley, Citation2018). However, cultural policy researchers' unfamiliarity with the financial market and their limited access to financial institutions mean that there is a surprising lack of scholarly investigation in those areas. This is problematic because using finance in public cultural investment – i.e. bringing financial institutions and products to the domain of cultural policy – raises many challenging questions on the relationship between culture, the state and the (financial) market.

Against such a backdrop, this paper presents an original research that explores the interface between cultural policy and finance by looking into the South Korean government’s use of venture capital. It was the beginning of the new millennium when the Korean cultural ministry and the film council began partnering with venture capital companies to raise public-private funds dedicated to the cultural and film industries. This unprecedented, bold policy experiment has had significant impact on the cultural industries by increasing capital provision, creating a “cultural venture capital market” and transforming the structure of cultural investment. Questioning the dichotomist understanding of state-market relations, this paper demonstrates that the development of cultural venture capital financing in South Korea is a “state-led regulated financialisation” project. In this project, the government has played strategic roles in creating, growing and “taming” the cultural venture capital market. Importantly, profit maximisation in this market is seriously limited by not only government regulations but also the strategic behaviour of private investors (cultural distributors).

In the following sections, I will first theorise the central roles played by the Korean state in promoting the cultural industries, and then examine what motivated the government to institutionalise venture capital financing for public cultural investment. Next, the distinct nature of the cultural venture capital market is explored in relation to the fundamental features of cultural financing, that is, high risk, the prevalence of project financing and the lack of finance capital. Then, I will analyse the tensions and negotiations between three participants in this peculiar financial market. Last but not least, I will critically reflect on the Korean cultural policy’s increasing dependence on the financial market against the broad trend of the financialisation of economy and public policy.

For this research, I used a mixed methodology: a review of policy documents and news reports on cultural financing and venture capital; an observation of a networking event among venture capital firms and cultural businesses and attending a lecture by a fund manager on cultural investment; and interviews in May–June and October–November 2019. The 15 anonymous interviewees included fund managers, venture capital experts, policy makers and a film distributor/venture capital investor. As the details of venture capital funds are not disclosed to non-investors, sources of information included the available public data published by Korea Venture Investment Corp., Korean Venture Capital Association and Disclosure Information of Venture Capital Analysis.

The following discussion will focus on film financing: the film industry was the initial policy target when the cultural ministry began using venture capital in the early 2000s; and it has been regarded as the most profitable among the cultural industries and attracts the half of the government-backed VC investment today. However, the use of venture capital should be seen as a cultural industry policy rather than a film policy as it covers a wide range of cultural businesses and increasingly facilitates cross-industry investment within the broader cultural sector.

The state as “a visible hand”

The South Korean state demonstrates a distinct approach to supporting the cultural industries: instead of passively addressing market failures, it willingly creates markets to channel resources to the industries. As such, a fundamental aspect of the Korean cultural industry policy is the state’s active role as “a visible hand” that steers the cultural market economy (Hong, Citation2019; Lee, Citation2019, Citation2020).

Commentators often highlight the ever-increasing public support for cultural businesses since the 1990s against the backdrop of neoliberal reform and globalisation, hinting that the conventional discourse (and critique) of neoliberal policy does not easily capture what has happened in Korea (Chung, Citation2019; Jin, Citation2014; Kwon & Kim, Citation2014; Otmazgin 2011; Ryoo & Jin, Citation2020). For example, Jin (Citation2014) notes that state power has not diminished but has even reinforced when it comes to cultural policy. Despite observing a fluctuation of the level of state interventionism across different governments (Ryoo & Jin, Citation2020), he concludes that the “developmental state” in Korea is not dead and neoliberalism makes no fundamental change to the underlying shapes of its cultural policy (Jin, Citation2014). Similarly, Chung (Citation2019) argues that the Korean cultural industry policy is “neo-developmental” as the characteristics of the developmental cultural policy maintain while the understanding of culture and the making of cultural policy has been democratised since the 1990s. However, the usefulness of “developmental” as an analytical concept is dubious. The developmental state refers to the strong state in East Asian countries such as South Korea, Taiwan, Singapore and Japan that steered the nation’s rapid industrial catch-up by making active interventionist industrial policy (Onis 1991; Woo-Cumings, Citation1999; White, Citation1988). Importantly, the developmental state of Korea from the 1960s to 1980s had an extremely strong cultural dimension – a comprehensive authoritarian cultural policy characterised by statist propaganda and heavy censorship. Thus, it is problematic to use “developmental” (e.g. Kwon & Kim, Citation2014; Jin, Citation2014; Otmazjin, Citation2011) as a label for the state-led cultural policy in democratic Korea. Here, it would be helpful to consider that Japan has never had a developmental cultural policy and the authoritarian cultural policy in China today looks closer to Korea’s developmental cultural policy of the 1970s.

It is within such a context that I have explored the complexity and inherent conflict within the policy, as a product of the parallel movement of democracy and the market economy (Lee Citation2019 and Citation2020). That is, contemporary Korea as a “new patron state” goes far beyond being a benevolent patron for culture to dynamically facilitate the cultural market economy. The unevenness of the neoliberal reform means that traditional industries and big businesses are under more neoliberal pressures whilst the government shows a big commitment to new industries such as tech start-ups and cultural businesses. When it comes to cultural industry policy, what is notable is the Korean government’s “contextualised” understanding of the market – not as the unitary, self-regulating system but as a set of economic activities and institutions situated in a specific policy environment (Mazzucato, Citation2013; Polanyi Citation2001[1944]). That is, the development of the cultural industries requires state interventions and there is “nothing unusual” in state support for cultural producers and enterprises. The government is keen to identify sectors/sub-sectors to develop, invest in technology, push private sector actors to growth areas and initiate strategic collaboration with private sector actors (Jin, Citation2014; Kwon & Kim, Citation2014; Lee, Citation2019, chapter 5; Lee, Citation2020). Its support includes infrastructure provision, subsidies, export support and so-called “policy finance” including investment via venture capital (VC) funds. Such an active policy has provided a fertile ground for the Korean cultural industries to quickly expand: between 1999 and 2018, the film industry grew by 890% (to the revenue of 5,889.9 billion won), the broadcasting industry by 625% (to 19,762.2 billion won), the music industry by 1,605% (to 6,097.9 billion won) and the games industry by 1,585% (to 14,290.2 billion won).Footnote2

However, there exists inherent tension in the cultural industry policy because it is often treated as an industrial policy and the industrial concerns are not necessarily coincided with cultural concerns. The policy promotes small and independent productions to increase the diversity in the nation’s cultural life; at the same time, it is very keen to expand the overall size of the cultural industries and their export capacity. As a following section will show, these different policy goals and agendas are mixed in the government use of venture capital. Furthermore, using the financial market and financial actors add more complexity to the policy. It is because the logic of finance – the maximisation of short-term profit and shareholder values – can contradict the policy’s cultural concerns and does not necessarily translate into long-term growth of the industries. This means that, in order to use finance as an effective means of cultural industry policy, the government should be capable to “collibrate”Footnote3 (Jessop, Citation2016, pp. 171–172; Lee, Citation2019, p. 13) the different – cultural, industrial and financial – logics. This challenging task involves carefully regulating and incentivising venture capital companies as well as private investors.

The emergence of finance as a cultural policy tool

It was the mid-1990 when the cultural industries began drawing attention of venture capitalists. Ilshin Investment Co. made news headlines by being the first VC company which invested in film production by covering entire production costs of several film projects and even directly distributing the resultant films (Korea Economic Daily, Citation1998). Its huge success quickly made the financial industry see film making as a potentially profitable business. Soon several private VC funds were created and filled some gaps in cultural financing caused by the withdrawal of business conglomerates from cultural business – after having invested in cultural production for some years in the 1990s – in the aftermath of the 1997 Asian financial crisis (Kim, Citation2015; Paquet, Citation2005, pp. 43–44). The trend of financialisation of cultural investment continued with the emergence of several “netizen funds” that were raised by profit-seeking Internet users and covered fractions of film and musical production costs (DongA Ilbo, Citation2002; KOFIC, Citation2000). Still, private VC funds and netizen funds hardly stabilised cultural financing as investors were hypersensitive to the whims of the market. Film production relied mostly on so-called “Chungmuro capital” (named after Korea’s film district) raised by film distributors; other cultural businesses were still emerging and lacking stable funding sources. Thus, the cultural industries – especially the highly-organised film industry – lobbied the government for stronger support, including an increased “capital” provision (KOFIC, Citation2000).

The arrival of the liberal Kim Dae-Jung government (1998–2003) was a significant turning point. His presidential election manifesto included complete abolishment of cultural censorship,Footnote4 creating an arm’s length film council, and introducing VC funds for cultural and film industries (Interviewees 7 and 8). These measures had been put forward by cultural activists, who were involved in the protectionist “screen quota movement” in the mid-1990s, and were taken up by Kim’s election camp. The Kim government willingly implemented them. The emerging consensus was that “government intervention via finance was necessary” (Interviewee 8) because the existing policy tool (subsidy) alone could not increase capital supply for the cultural sector. Using VC funds was seen as a useful policy tool as they would involve matching funding. Policy makers thought that this would give “powerful support [to the industries] although the budget was not as big as that in France” (Interviewee 1).Footnote5 This policy proposal as welcomed by cultural producers who struggled to secure bank loans due to the lack of collateral (Interviewees 5 and 7). It was also justified by the belief that supporting the cultural industries would benefit ordinary people who enjoy popular culture whilst arts subsidy serves for only a limited number of people (Interviewee 5).

It will be useful to consider the overall restructuring of the Korean economy after the 1997 financial crisis. The expansion of the venture capital market after the crisis was an outcome of the government’s deliberate push. In order to boost financing for tech start-ups and SMEs (so-called ventures businesses), the Korean state grew a venture capital market by directly providing capital and partnering with venture capital companies (Baygan, Citation2003). Indeed, the emergence of a cultural venture capital market was part of the bigger package of the state-led creation of capital markets. The establishment of the KOSDAQ stock market in 1996 also reinforced the growth of the VC market. In 2000, a state venture capital company was established to make direct investments into select start-ups and SMEs and to provide management know-how. At the same time, the government and its agencies began working closely with private venture capital companies to create VC funds by matching private investments. In this way, numerous public-private VC funds were quickly set up in several policy areas. As such, cultural industry policy in the post-1997 years was heavily influenced by what was going on in the broader economic sectors in the country.

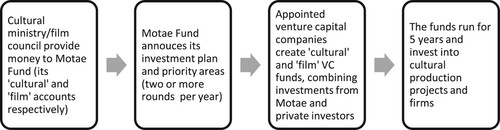

In 2000, the cultural ministry and the film council began directly partnering with several venture capital companies to create cultural and film VC funds. In 2006, the government centralised state venture capital investment by setting up a massive Motae Fund (fund of funds, or “mother fund” in Korean) under the SME ministry. The Motae Fund invests in numerous VC funds (“offspring funds”) for start-ups and SMEs in the various industries from bio to healthcare, ITC to culture. Consequently, on behalf of the cultural ministry and the film council, the Motae Fund began investing in the cultural and film industries from 2006 and 2010 respectively. Although Motae works with venture capital companies, it is the government (and the film council) who define the rules of the game by setting goals for the funds and regulating their operation.

Cultural and film VC funds are essentially hybrid (public-private) funds, where Motae’s initial investment is matched by private money. Selected VC companies function as a general partner of the funds (“limited partnership funds”) while investors participate as limited partners. A fund is typically made up of money from Motae (50-60%), the venture capital company (1-10%) and 3–4 private investors (40%) (Interviewee 13).Footnote6 They are professionally run by fund managers for five years. The following summarises how cultural and film VC funds are created every year ().

This method of state VC investment differs from the policies that are focused on tax expenditure. For example, the French government offers tax deductions to investors of SOFICA (an investment vehicle specialised in backing film and audiovisual production) (EAO report; Walkley, Citation2018, pp. 71–72). Similarly, the UK’s Enterprise Investment Scheme (EIS) offers tax relief to encourage venture capital investment in high-risk companies, including film production companies (GOV.UK, Citation2020). In contrast, the Korean government (and the film council) directly provide venture capital and take a more hands-on approach to regulating and monitoring the operation of each VC fund.

Cultural venture capital market

Venture capital company refers to a financial institution that raises and provides capital to start-ups and SMEs that have competitiveness but lack capital for further growth (Gompers & Lerner, Citation2001; KVCA, Citation2019b). Typically, a venture capital company acquires and keeps a stake in these firms for several years, until it realises capital gains, ideally through the firms' successful IPOs in the public stock market. As of 2018, approximately 160 venture capital companies operate in the broad venture capital market in Korea, running 806 VC funds (KVCA, Citation2019a, p. 19).Footnote7 Although a remarkable amount of venture capital is put into cultural businesses such as film, games and commercial musical productions (which altogether represents more than 10% of the total venture capital raised in Korea), the broader VC market still regards “culture” as a very “special area”. A venture capital expert says:

In comparison with manufacturing and ITC, culture along with bio are regarded as special areas. It is because investing in these two areas can be carried out only when there are specialised fund managers. For cultural investment, fund managers should have knowledge in cultural industries and experience in project investment. (Interviewee 11)

Now, I will briefly explain how cultural VC investment works in relation to three peculiar features of cultural production. First, it is widely known that cultural production is a risky business due to supply and demand uncertainty (Caves, Citation2000; Cohen, Citation2017; Hesmondhalgh, Citation2019; Morawetz et al., Citation2007). Big cultural companies such as Hollywood studios and Korean cultural conglomerates whose business integrates film production and distribution (and exhibition too in the case of Korea) are in a better position to manage risk by cross-subsidisation within the firms. However, the business of micro-, small- and medium-sized cultural producers has no such buffer, finding it difficult to attract investment. Hence, the government’s design of VC funds focuses on motivating private investors by boldly sharing their risk (by 50-60% in many cases). A policy maker aptly sums up how this works:

[Without Motae], the failure of private investment would mean 100% loss of the money. If [Motae] is putting money by a certain percentage, the risk is shared by that percentage. In short, the government provide a certain guarantee. (Interviewee 5)

We should notice that the government played key roles in institutionalising VC investment in cultural “projects” via relevant legislation. The Regulations on the Registration and Management of Venture Capital Companies Specialised in Investing in SMEs designates cultural production projects as one of the “legitimate” areas for venture capital investment in Korea.Footnote10 This allows cultural production projects to access public support initially designed for start-ups and tech ventures. In turn, cultural producers are required to set up a temporary cultural SPC – special purpose company that temporarily exists during the project period only – to keep their project finance separate from personal finance and keep the former transparent.Footnote11 These measures made cultural production projects more appealing to venture capitalists.

Third, cultural VC investment hardly attracts “finance capital”, that is, money from financial institutions such as banks and pension funds. Simply speaking, financial institutions in Korea are not convinced “if cultural business can really generate profit” (Interviewee 12). The situation is very unlike Hollywood, where studios and large independent producers draw capital from commercial banks, so-called entertainment banks, wealthy individuals, and hedge and private equity funds (Cohen, Citation2017; Dewaard, Citation2017; Landry & Greenwald, Citation2018; Morawetz et al., Citation2007). Unable to access finance capital, Korean cultural producers traditionally relied on personal capital (e.g. personal borrowing) and “industry capital” (money raised within the cultural industries, especially from distributors). Interestingly, state-led VC investment has not broken away from this practice; rather, it channels industry capital to cultural producers via the cultural VC market. In the other words, private investors of cultural and film VC funds tend to be cultural distributors (film distributors, games publishers and broadcasters), licensing companies, online ticketing companies, online platforms, big production companies, and toy makers (in the case of animation).

The government’s use of VC has had a notable “crowding-in” effect, luring in private investments and consistently increasing the pool of capital for cultural industries, though there were ups and downs depending on the overall economic environment. The following table shows that several cultural funds have been created annually by the combination of public and private money ().

Table 1. VC funds under Motae’s cultural account 2006–2016 (unit: 100 million won).Footnote14

Between 2006 and 2016, cultural and film funds together raised a total of 1,868.1 billion won (approx. US$1.61 billion) and invested in more than1,600 projects and companies in the broader cultural industries (MCST, Citation2017, p. 1). The most popular areas for investment are film (54% of cultural and film funds), musical shows (12%) and games (11%) (p. 2). A policy maker aptly points out, “as you can see from the ending credit of a film, films cannot be produced without these funds” (Interviewee 2).

Tensions, negotiations and balancing acts

The creation of a cultural venture capital market was a “state project”, but its operation requires intricate balancing between different goals held by different stakeholders. As the most resourceful and powerful actor in this market, the government sets the basic rules of the game, while depending on capital input from private investors and the financial expertise and brokerage provided by venture capital companies. In this sense, Korea’s cultural venture capital market is an “overlapping zone” among different interests (Vestheim, Citation2012).

Government agendas and regulations

In addition to expanding and stabilising cultural financing, policy makers also want VC funds to promote diversity of cultural forms and genres and attract private investments to riskier areas (KOFIC, Citation2019, p. 2). For example, 100% of film funds (backed by Motae’s film account) should be invested in domestic film production with focus on pre-production, early-stage production, small-and-medium budget film, independent film, etc. For instance, the following shows the key requirement for “small-and-medium budget film funds”:

The funds should invest the 100% of its money into Korean film. 45% or more of the total fund should be invested in the production of medium-budget film, and 15% in small-budget film production … Investing into the following sectors is recognised as investment into small-budget film production: 1) investing in planning and pre-production; 2) investing in films funded by the film council (indie film, small-budget film, animation film and planning and preproduction). (Korea Venture Investment Corp, Citation2019: 3)

Table 2. Motae Fund cultural account’s investment plan for 2019 (billion won).

The VC companies should invest 60% of each fund in its priority area while they can invest 40% in more lucrative areas such as blockbuster film production or a games company. 30% of the fund can be invested in non-cultural business which could be more profitable. Such terms and conditions are designed to incentivise venture capital companies by allowing cross-subsidisation within a fund as well as regulating their profit seeking at the same time.

There are also regulations on investors and investees. For example, the VC funds are banned from investing in production projects directly run by private investors. A few years ago, the government even banned all funds from investing in films that would be distributed by cultural conglomerates (large film distributors). However, such restrictions on cultural funds were removed in 2019 as the film industry’s boom was burst in 2018 and there was an urgent call for Motae’s support (Kukmin Ilbo, Citation2019); still, the rules for film funds remain stricter (cultural conglomerates cannot be investors, nor can the VC funds invest in the films that they distribute).

Private investors' pursuit of strategic interests

As mentioned earlier, private investors of cultural and film funds tend to be cultural distributors. Their ultimate concern is to access cultural content which they can distribute, publish, license and exploit in various ways and to secure capital investment into cultural products that they will distribute. This is why they are called “strategic investors” as opposed to “financial investors” (such as financial institutions) whose only concern is return on investment. However, private investors’ strategic behaviour causes some visible tension. A widely talked-about issue is the tendency that they enlarge capital injection into their chosen projects by using Motae’s money as a leverage. For example, a distributor invests 200 million won into a Motae-backed VC fund, with an expectation that the fund will invest 400 million won or more into the production of the content it distributes. What is notable here is the investors’ prioritisation of strategic interests over the immediate profitability of the fund itself; in case of big film distributors (conglomerates) who own cinema chains, profit from ticket sales is treated as more important than return on their VC investment (as mentioned earlier, cultural VC funds can invest in films that are distributed by those conglomerates) (Interviewee 12). A fund manager observes:

When deciding to invest into the VC funds, private investors used to consider the stable supply of money to projects of their choice and their access to valuable content, over the issue of profitability. This is the same today. […] They are not even bothered about individual investment decisions of the VC funds because strategic interests are their utmost priority. (Interviewee 13)

Such strategic behaviour looks irrational from the financial viewpoint; as fund managers say, “prioritising the strategic interests of industry capital does not necessarily lead to good profit” (Interviewees 10 and 12; Kim, Citation2015). The leverage investment is often criticised by media and cultural activists as abusing public money (Interviewee 3). In 2013, the Motae Fund found that a venture capital company promised a big film distributor a leverage investment in a secret agreement (Kukmin Ilbo, Citation2019). It was also revealed that some film distributors selectively used VC funds to maximise their advantages (e.g. they directly invested in promising projects while using VC funds to bring in external investments to the rest of their distribution line-up). What is more, the profit rate of those funds used for leverage investments was much lower (−19.7%) than that of funds without leverage investments (17.3%) (Kukmin Ilbo, Citation2019). Yet, it is interesting to remember that a similar practice exists in Hollywood: very profitable projects (such as sequels to blockbuster films and animated films) are generally excluded from so-called slate financing that involves external investors such as banks and hedge funds (Cohen, Citation2017, 30). Both the cultural ministry and venture capital companies see private investors' strategic behaviour as problematic. Yet, they tend to reluctantly tolerate it because cultural VC financing depends on industry capital. Any written agreement on leverage investment is banned yet this practice still appears to prevail.

Another very important finding is that the government’s use of VC financing in public cultural investment has resulted in the overall transformation of the cultural investment and risk-sharing structure. Since the 2000s, networked financing, which actively uses the VC market, has become a dominant mode of cultural financing, especially film financing. That is, a film producer directly receives “main” funding (20-30%) from its distributor, and partial funding (70-80%) from various Motae-backed VC funds – in which the distributor takes part as an investor – as well as other investors (Kim, Citation2015, p. 17). It is argued that this way of stabilisation of capital provision substantially contributed to the strengthening of the film industry’s competitiveness (p. 12). VC funds allow investors to spread risk as the funds invest in multiple productions, sometimes including productions funded by their competitors (Interviewee 12). They also facilitate investment across different branches of cultural industries and non-cultural industries to maximise risk dispersal. For example, internet platforms, via VC funds, invest in a diverse range of productions from drama, comics, film, games to e-commerce to maximise their strategic interests and spread risk as widely as possible.

Via intra-industry, inter-industry and trans-industry investments coordinated by venture capital companies, Korean cultural investors today manage risk though cross-subsidisation within their investment portfolio. Such networked financing is comparable to “slate deals” and “co-production deals” that are two well-known risk-reduction strategies developed in Hollywood (Landry & Greenwald, Citation2018, pp. 70–73)Footnote12 and Japan’s “production committee system” (Kawashima, Citation2019) that distributes investment opportunity and risk-bearing among different branches of cultural industries. Those financing practices are purely driven by market forces in two of the world’s biggest cultural economies. In contrast, a similar but more extensive system of investment- and risk-sharing has developed in Korea’s smaller cultural economy because of active intervention by the state.

Limited financial returns for venture capital companies

Cultural venture capital companies are part of the nation’s booming financial industry, but their management of Motae-backed VC funds is tied to government regulations and investors' strategic interest. This seriously constrains profit maximisation and thus results in overall low return (Kim, Citation2015). It is reported that the average profit rate of all 21 closed cultural funds for the five years up to 2018 was −3.82%, which is comparable to that of Motae’s SME funds (7.5%) or the average profit rate of all funds backed by Motae (3.43%) (The Bell, Citation2018; Yonhap News, Citation2018). The low returns seem to be inevitable as the funds often prioritise riskier areas. Another reason is the dominance of project investment whose maximum return is limited. Still, VC companies are strongly incentivised by the management commission (2.5% of the fund) as it provides them with a stable source of income for five years. If their investment goes well, they receive a bonus on top of the return on their own investment into the funds. For their long-term survival and reputation as cultural venture capitalists, working with Motae (the government and the film council) is vital as it is “very hard to create a fund for cultural investment, without money from Motae” (Interviewee 4). In addition, the Motae brand signals reliability and stability, thereby attracting private investors.

The current generation of fund managers in charge of cultural and film funds have a background in cultural or entertainment businesses and self-identify as supporters of the cultural industries. A venture capital expert observes:

Basically, there are many fund managers who have good understanding of and passion for the cultural industries. They want the industries as a whole to grow. They are from film production, film distribution, games production and entertainment companies. They hope the industries further grow and produce high-quality content. (Interviewee 10)

One of our past funds yielded very high profit because of its successful equity investments into an internet media company, a games company, an entertainment management firm, an internet shopping site, a TV drama production house, etc. Project investment alone cannot generate profit. In the case of investing in animation production projects, it can lead to a huge loss (−50%). Then, equity investment fills the gap. (Interviewee 4)

Of course, venture capital companies aspire to be more in line with the rest of the financial sector and pursue profit maximisation more freely. For this to happen, they would need an influx of private finance capital and deregulation. Attracting finance capital could expand the cultural VC market per se and restore financial rationality. It is interesting to see fund managers justifying the need for finance capital in terms of “artistic autonomy” and “freedom”. For instance, the investees would be free from the strategic interests of distributors (e.g. using commercially proven conventions preferred by distributors or giving the investors access to IP), and cultural financing would become less submissive to the power of industry capital (Interviewees 4 and 12). Yet, securing finance capital is hard because financial institutions are still wary of betting their money on culture and are sensitive to the ups and downs of the market. There are exceptional cases of banks investing in cultural industries, but these are rather accidental as their motivations are not entirely financial; e.g. the head of the bank has an interest in culture, or the bank is under heavy governmental influence (Interviewees 4 and 13).

In the pursuit of profit, VC companies also wish for deregulation of the Motae Fund. But they are not (yet) in a strong position to loudly call for deregulation or actively negotiate with the government.

We would want deregulation … as those rules are obstacles for running the funds. In particular, the threshold for the minimum investment in the priority area should be lowered. […] Then, the funds would generate more profit and private investors would be more attracted. (Interviewee 4)

Only a couple of investments out of many generate good profits so our funds need more flexibility. For this reason, we hope things could be deregulated. (Interviewee 13)

All Motae-backed VC funds should deliver both public interest and profitability. But the rules for those culture/film-related ones are tighter and more complicated, reflecting the internal tension and complexity in cultural industrial policy itself. The government tries to find a balance between the logic of cultural policy and that of finance by incrementally finetuning its regulations depending on the circumstance. For example, the regulations become stricter when the cultural industries thrive and more easily attract private investors; and they become loosened and more incentives are provided when the industries struggle with raising capital (e.g. the slump of the film market in 2018 or the Covid crisis since 2020). Being aware of the tensions between different interests held by different parties, the cultural ministry regularly engages in conversations with other parties (Interviewees 4 and 6) and constantly modifies relevant regulations. VC companies, in turn, try to nurture their long-term relationship with the government and private investors not only through good performance (meeting policy goals, assisting investors’ strategic interests and generating decent capital gains) but also through informal meetings and socialising. A fund manager notes, “Motae will want to work with a VC company again even though the return of its previous fund was not good, if the fund successfully addressed the policy agendas” (Interviewee 4).

State-driven, regulated financialisation

We should reflect on the Korean cultural policy’s use of venture capital against the backdrop of the global trend of “financialisation” of economy, society and public policy. Financialisation broadly refers to “the increasing role of financial motives, financial markets, financial actors and financial institutions in the operation of the domestic and international economies” (Epstein, 2005: 3 cited in Sawyer, Citation2013, p. 6). As a multifaceted phenomenon, it not only means deregulation and expansion of financial markets, increasing profits accrual through financial channels and shifting power from industry to finance but it also involves cultural and behavioural changes in non-financial businesses (their taking of shareholder value maximisation as a core principle of corporate management) and the government’s rising dependence on the financial markets (Krippner, Citation2005; Palley, Citation2008; Sawyer, Citation2013; Van der Zwan, Citation2014; Vercelli, Citation2019). Furthermore, manifesting in the form of housing bubbles and credit-driven consumption, financialisation greatly affects our everyday life. Being associated with the economic policy focusing on globalisation, small government and labour market flexibility, it is criticised for having engendered many socio-economic problems such as declining investment in productive activities, tepid real economic growth, rising household debts, manufacturing job loss, wage stagnation and widening income inequality (Palley, Citation2008).

Obviously, the Korean cultural ministry’s use of venture capital financing is an extension of financialisation into the sphere of culture and also as an indicator of the rising influence of financial imperatives in policy making. This is in line with the financial turn in industrial policy in Korea and policy makers’ increasing reliance on the financial markets. Now the nation’s SMEs and start-ups are supposed to attract capital via the financial market rather than relying upon government protection and subsidy (Baygan, Citation2003); the venture capital industry itself – as a new post-industrial economic sector and a product of active state intervention – has grown quickly thanks to the financialisation of the industrial policy. It is telling that cultural policy makers of the early 2000s thought that using VC was more “market-friendly” and giving a new identity (“venture business”) to cultural businesses would help them to access state support (Interviewees 2 and 5). The investment of Motae-backed VC funds is managed by financial actors and any discussion of it in the media or policy circles essentially employs a financial vocabulary.

However, we should resist taking a dichotomist view of the relationship between the state and the (financial) market. Instead of simply seeing the use of VC for public cultural investment as an example of financialisation (thus neoliberal cultural policy), we should develop a more nuanced understanding by looking into its multivalent nature and inner dynamics. First, I argue that the development of the cultural VC market should be seen as a “state-driven and regulated financialisation”. This regulated financialisation was triggered not by financial institutions’ ruthless intrusion into the realm of culture for profit seeking but by a series of purposeful policy initiatives: legislation, the introduction of a new organisational form (“special purpose company”) and norms (e.g. separating project finance from the producer’s personal finance),Footnote13 the government’s capital injection, and regulation. As such the state has played “absolutely important roles” creating and maintaining the cultural VC market, and these roles are “irreplaceable” (Interviewees 2 and 5). A fund manager states,

Without Motae, we would not be able to create cultural or film funds at all. If Motae’s investment disappears, the consequence would be more than a proportionate reduction of capital to 40-50% of the currently available amount (as Motae supply 50-60% of the capital for a fund). As such, it is important for [this capital market]. (Interviewee 13)

Second, I want to draw attention to the social and sector-specific characteristics of this financial market. The aforementioned policy initiatives have relied on “social process”, in which mutually dependant participants develop long-term relationships, communicate via both formal and informal channels and share an understanding that the government’s capital injection is essential for the stability of the market. Moreover, sectoral specificities critically limit the operation of financial logic in this peculiar financial market. Typically, venture capital companies heavily affect the management of invested firms via business coaching and by intensely monitoring the firms’ performance. However, in the current structure of cultural financing in Korea, venture capital companies’ input into investees’ business and management is quite limited. It is because one-off project investment prevails and private money comes from cultural distributors who have strategic interests. Unlike what the theory of financialisation says, profits for investors are accrued from activities in the real economy (e.g. ticket sales and access to IP) rather than from financial activities (e.g. return on VC investment). Because the investors, as insiders of the cultural industries, do not suffer from information asymmetry, the main task of venture capital companies is reduced to mobilising capital, coordinating investment and managing risk for the investors. Indeed, cultural financing functions as “the central risk distribution mechanism” for the cultural industries and an important shaper of their business strategies (Morawetz et al., Citation2007, p. 422). As such, the use of VC for cultural financing in Korea is an interesting case of regulated financialisation in which the drive to maximise short-term profit and shareholder value is greatly constraint by the specific sectoral conditions (Christophers, Citation2015; Van der Zwan, Citation2014).

However, it is also observed that forces of financialisation come from the government itself. The cultural and film accounts in the Motae Fund are under increasing pressure from the parliament and the economic ministry that seek “value for money”. For years, some members of the parliament have criticised the high proportion of public money within the VC funds and the funds’ low profitability (The Bell, Citation2018b; Yonhap News, Citation2018). Similarly, the economic ministry’s evaluation of the Motae Fund narrowly focuses on profitability, making its operator, the Korea Venture Investment Corp., sensitive to the profit rate of VC funds (Interviewees 3 and 9). Wanting to demonstrate a more persuasive and quantifiable policy effect, the cultural ministry began highlighting the importance of equity investment in firms: e.g. nurturing potential “unicorns” (i.e. a privately held start-up valued at 1 trillion won, or US$1 billion) (Interviewee 9). There are several cultural firms which received an investment via Motae-backed funds in the past that have been successful enough to be potential unicorns: e.g. Bluehole (the maker of Battlegrounds, the globally popular game) and Big Hit Entertainment (the talent agency managing BTS). As their successes have set a benchmark, policy makers have begun to believe that it is not impossible for cultural investment to generate very handsome capital gains via IPOs. Similarly, the cultural ministry wishes to attract finance capital to expand the cultural venture capital market and curtail the power of big distributors. For instance, Motae’s announcement in May 2019 states that it would prefer venture capital companies who attract “private financial investors who are not part of cultural industries” (Korea Venture Investment Corp., Citation2019, p. 6). Yet, the government’s increasing embrace of the financial logic and expectations results in an oxymoron. It is because if cultural investment can produce handsome returns and attract enough private money (especially finance capital), then the cultural VC market would not need state investment in the first place.

Conclusion

This paper has presented an original research into the use of finance in state cultural investment and provided rare insights into the operation of cultural venture capital financing. The South Korean case aptly demonstrates how the government can strategically uses venture capital companies and the venture capital market to expand capital provision for the cultural industries and achieve other policy goals. Significantly, this process has been part of the Korean state’s project to create a broad institutional environment – formal and informal rules, relations and organisational arrangements – within which a certain set of cultural producers, firms and activities are organised as “cultural industries” and these industries grow. The Korean government’s purposeful utilisation of market forces to channel resources to the cultural industries not only questions the dichotomist perception of the state vs. the market. But it also challenges the neoliberal idea of the market as a singular self-regulated system by showing how the venture capital market is created, nurtured and tamed by the state. I have also pointed out the importance of sector-specific business relations and the dominance of industry capital in shaping the operation of this financial market. Unlike the neoliberal idea of the market as asocial and autonomous, markets (including financial markets) are socially embedded, and each of them shows distinct sector-specific features.

Observing how much the cultural industries – or cultural economy – are shaped by state intervention and social relations, we realise that cultural policy has potentially substantial scope to play active roles in supporting cultural producers and businesses. Using finance is one of the ways to do this. International cultural policy makers who want to use finance for cultural investment can learn helpful lessons from the Korean case, especially the importance of creating a policy that helps to reduce risk borne by private investors, constrains profit-seeking of financial actors, and flexibly responds to the ups and downs of the cultural market. It is also critical to consider the broader impact of state intervention: for example, the restructuring of cultural investment and risk-sharing structure in Korea was an unintended but remarkable consequence of the government’s use of venture capital.

Finally, I suggest the following two issues need further thought. First, the convoluted tension within cultural industry policy. What is interesting about the Korean case is the government’s refusal to choose either “culture” or “industry” and its attempt to nurture both through exceptionally active support from the state. While there is a strong consensus on state support, how the two goals of cultural industry policy can be aligned discursively, institutionally and organisationally is yet to be explored theoretically and empirically. Bringing in finance to cultural industry policy generates further complexity. So far, the Korean cultural ministry has kept the forces of financialisation under control. But as long as it uses the financial market, it cannot avoid the situation where its policy is evaluated in terms of the return on investment. Even among policy makers, there are divergent perspectives of the purpose of Motae-backed cultural and film funds. If the cultural ministry focuses more on “cultural” and “industrial” concerns, some members of parliaments and the economic ministry are keen to address “financial” concerns. How cultural ministry negotiates with those other policy makers will hint how the regulated financialisation can sustain in the environment where the success of public policy is increasingly determined by its performance in the financial market.

Second, this research draws our attention to the difference between industrial actors (investors-cum-distributors) and financial actors in terms of their motivations and behaviour. Whilst the investors' opportunistic behaviour is criticised, it should be noted that they are insiders of the cultural industries and have stakes in cultural production. In contrast, financial investors such as banks would bet on cultural businesses only when there is satisfactory return on their investment and would quickly leave for higher return elsewhere at any time when the cultural market enters a downturn. This makes us to freshly realise the importance of industry capital and consider possible ways to increase it and make it feed a “long-term” growth of the cultural industries. In this sense, it will be also interesting to critically contemplate the roles played by big cultural conglomerates and distributors in cultural financing, especially the conditions under which their commercial (industrial) interests could serve as a buffer against financial investors' pursuit for capital gains and shareholder value maximisation. This inquiry will be relevant to the cultural industries and cultural financing elsewhere such as the US and the UK, in which the operation of financial actors is more visible.

Post-script

Covid-19 has severely hit South Korean cultural industries. In addition to an emergency rescue package (subsidy), the government has recently announced a plan to increase its input to the cultural VC market and take more risk. As many kinds of markets have stopped functioning properly, however, we need to observe how the cultural VC market will respond to this. As physical cinemas are one of the worst victims of the pandemic, the viability of film distributors’ current business model and their strategic investment behaviour might be called to question.

Acknowledgements

I thank Karin Ling Fung Chau, Takao Terui and anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments and suggestions.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Hye-Kyung Lee

Hye-Kyung Lee is Reader in Cultural Policy, Culture, Media and Creative Industries, King’s College London, UK. Her research is centred on state policies on the arts and the cultural industries. Her publications include Cultural Policies in East Asia (Palgrave Macmillan 2014), Cultural Policy in South Korea: Making a New Patron State (Routledge 2018), Asian Cultural Flows: Cultural Policy, Creative Industries and Media Consumers (Springer 2018) and Routledge Handbook of Cultural and Creative Industries in Asia (2018). She is working on a book on the cultural industries and the state in South Korea.

Notes

1 See https://www.creativeengland.co.uk/creativegrowthfinance/ (accessed on 7 February 2021).

2 For more details, see Ministry of Culture and Tourism (2002) Munhwasaneopbaekseo (Cultural Industries White Book) and Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism (2019) Kontencheusaneop baekseo (Content Industries White Book).

3 ‘Collibration’ refers to effectively managing the co-existence and co-working of different modes of governance such as exchange (the market), command (the state), dialogue (network) and solidarity (civil society; social movement). When there is governance failure or different governing modes are in conflict, the state is expected to ‘collibrate’, altering the weight of individual modes of governance and find a balance so that public policy can better adapt to social change or solve problems (see Jessop, Citation2016, pp. 171–172). This notion is useful to describe the role of the Korean state in balancing the multiple logics operating in the cultural VC market and keeping them compatible within the policy framework.

4 Officially, cultural censorship in South Korea was abolished by 1996 with the constitutional court’s ruling that film censorship was anti-constitutional. Still, soft censorship was carried out on popular cultural content such as film and entertainment in the form of ‘postponement of classification’ until 2001.

5 Korean policy makers were conscious of overseas examples of good cultural policy. When it comes to cultural industry policy, the main reference point was France where there was a strong support policy for a wide range of cultural industries. In the Korea-France cultural policy forum organised by the Korean film council in 2001, the French film council (CNC)’s support for film and audiovisual industries (1,343.8 million francs; approx. USD 207 million, 1999, except TV funding) was referred to (KOFIC, 2001, p, 9). It was much higher that the Korean film council’ spending including expenditure on managing venues and human resource (KRW 16.18 billion: approx. USD 14.2 million, 1999) (my communication with the KOFIC 2020).

6 Especially at the beginning of the policy, the government and the film council took more risk by offering 60-70% of the total investment for funds. For example, early film funds were raised in this way. Their ‘first-taking’ of loss also incentivised private investors. Today, Motae normally provides 50%–60% of the funds, and the risk and potential financial loss (or profit) are shared equally among all investors according to the size of their stake.

7 The Korean venture capital market significantly relies on public money: about 40% of VC funds is raised from public investors, including more than 20% from the Motae Fund and the rest from the Korea Development Bank and other public financial institutions. In general, private investors include commercial financial institutions, pension and endowment funds, business corporations, individual investors and so on.

8 For example, Daesung Venture Capital, Union Investment Partners, Isu Venture Capital, Solaire Partners, Timewise Investment and Ilshin Investment Co.

9 For VC companies, perspective project investment has both pros and cons. The biggest merit is its quick return: the first return for film investment occurs six months after the release; similarly, the investors for a commercial musical production normally collect the return in a few months because most musicals have a short run (Interviewees 1 and 3). But its notable limitation is that, even in the case of a box office hit, it is not likely to bring the investor an extremely high return that an equity investment can generate via a successful IPO. Meanwhile, games studios attract equity investment even from mainstream VC companies. This means that games along with bio, healthcare, ITC and service businesses is now a recognisable part of Korean VCs’ investment portfolio (KVCA, Citation2019a).

10 See article 7 of the Regulations at https://www.law.go.kr/LSW//admRulLsInfoP.do?chrClsCd=&admRulSeq=2100000178943 (accessed on 1 March 2021).

11 This requirement was introduced because, in the past, cultural producers such as film producers did not separate project financing from their personal financing, often leading to a situation where producers regarded investment into their projects as their personal income (interviewee 4). The Korean cultural ministry introduced ‘cultural SPC’ – as a temporarily existing paper company – in order to increase transparency in project financing and, thus, facilitate investment.

12 These are two popular methods of financing films in Hollywood. Slate deals (i.e., investing in a group of films produced by a studio, not a single film) are designed to reduce risk by spreading it across multiple films and multiple investors such as the studios, distributors, ‘senior lenders’ (banks, hedge funds or private equity funds), ‘mezzanine lenders’ (private equity funds or investment banks) and equity investors. Co-production financing refers to two or more studios sharing financing for a film. See Landry and Greenwald (Citation2018, chapter 4).

13 See end note 11.

14 Two funds that were being created as of 2016 (65 billion won; among these Motae’s contribution was 20.8 billion won) are excluded. The amount of funds fluctuated, reflecting the fluctuation of the venture capital market due to the lack of confidence of investors in the early and mid-2010s. The tightening of Motae’s regulations also made it hard to create VC funds.

15 The contribution of Motae among the VC funds varies depending on the nature of the funds. It tends to be smaller when it comes to commercially promising funds such as those dedicated to ‘converged content’, ‘culture-ITC convergence’ and ‘global content production’.

References

- Baygan, G. (2003). Venture capital policies in Korea. OECD working paper.

- The Bell (13.21.2018). Yesansakgam jeongchigwon munmae … suikseong nakje hupokpung (Heavily criticised by politicians and threatened of budget cuts … backlash against [Motae’s] low profitability).

- Caves, R. (2000). Creative Industries: Contract Between Art and Commerce. Harvard University Press.

- Christophers, B. (2015). The limits to financialization. Dialogues in Human Geography, 5(2), 183–200. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/2043820615588153

- Chung, J.-E. (2019). The neo-developmental cultural industries policy of korea: Rationales and implications of an eclectic policy. International Journal of Cultural Policy, 25(1), 63–74. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10286632.2018.1557646

- Cohen, J. N. (2017). Investing in Movies: Strategies for Investors and Producers. Routledge.

- Dewaard, A. (2017). Derivative media: The financialization of film, television, and popular music, 2004-2016 (Doctoral dissertation), UCLA. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/69w0v6n3 (accessed on 1 February 2020).

- DongA Ilbo. (2002). Netijeun peondeu munhwasaneop ‘keunson’ (Netizen funds, a big hand in the cultural industries).

- EAO (European Audiovisual Observatory). (2014). Impact analysis of fiscal incentive schemes supporting film and audiovisual production in Europe. Strasbourg: EAO.

- Gompers, P., & Lerner, J. (2001). The venture capital revolution. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 15(20), 145–168. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.15.2.145

- GOV.UK. (2020). Tax relief for investors using venture capital schemes https://www.gov.uk/guidance/venture-capital-schemes-tax-relief-for-investors (accessed on 8 February 2020)

- Hesmondhalgh. (2019). The Cultural Industries (4th ed.). Sage.

- Hong, K. (2019). Editorial: Culture and politics in korea: The consequences of statist cultural policy. International Journal of Cultural Policy, 25(1), 1–4. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10286632.2018.1557652

- Jäkel, A. (2003). European Film Industries. BFI.

- Jessop, B. (2016). The State: Past, Present, Future. Polity.

- Jin, D. Y. (2014). The power of the nation-state amid neo-liberal reform: Shifting cultural politics in the new Korean wave. Public Affairs, 87(1), 71–92.

- Kawashima, N. (2019). The production consortium system in Japanese film financing. In L. Lim & H.-K. Lee (Eds.), Routledge handbook of cultural and creative industries in Asia. (pp. 166–176). Routledge.

- Kim, Y. (2015). Hanguk yeonghwasaneobui tujagujowa sisajeom (Investment structure and implications of the Korean film industry). Seoulgyeongje May issue: 11-20. https://www.si.re.kr/node/52162 (accessed on 13 April 2020)

- KOFIC. (2000). Hangugui yeonghwasaneopgwa yeonghwajeongchaek (Korean film industry and film policy).

- KOFIC (Korea Film Council). (2019). Motaepeondeu yeonghwagyejeong eommu chonggwal hyeonhwang (A comprehensive report on the operation of Motae Fund film account).

- Korea Economic Daily. (22/06/1998). Gimseungbeom ilsinchangeoptuja suseoksimsayeok, maideoseuui son (Kim Seung-Beom in Ilshin Investment Co.’s lead fund manager, his Midas’s hands).

- Korea Venture Investment Corp. (2019). Hangungmotaepeondeu 2019 nyeon 2 cha jeongsi chuljasaeop gyehoek gonggo (Announcement of the second round of Korean Motae Fund’s investment plan 2019).

- Krippner, G. (2005). The financialization of the American economy. Socio-Economic Review, 3(2), 173–208. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/SER/mwi008

- Kukmin Ilbo. (2019.4.16). Manghal yeonghwa gateumyeon naratdon sseun yeonghwabaegeupsa (Film distributors spending public money for films destined to fail).

- KVCA (Korean Venture Capital Association). (2019a). 2019 KVCA Yearbook & Venture Capital Directory. KVCA.

- KVCA (Korean Venture Capital Association). (2019b). Kontencheutuja Paeseuteuteuraek (Content Investment Fast Track). KVCA.

- Kwon, S.-H., & Kim, J. (2014). The cultural industry policies of the Korean government and the Korean wave. International Journal of Cultural Policy, 20(4), 242–248. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10286632.2013.829052

- Landry, P., & Greenwald, S. (2018). The Business of Film: A Practical Introduction (2nd ed.). Roultedge.

- Lee, H.-K. (2019). Cultural Policy in South Korea: Making a New Patron State. Routledge.

- Lee, H.-K. (2020). “Making Creative industries policy in the real world: Differing configurations of the culture-market-state nexus in the UK and South Korea”. International Journal of Cultural Policy, 26(4), 544–560. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10286632.2019.1577401

- Mazzucato, M. (2013). The Entrepreneurial State: Debunking Public vs. Private Sector Myths. Anthem.

- MCST. (2017). 2017 nyeondo motaepeondeu munhwagyejeong unyonggyehoek (2017 operational plan of Motae cultural account). Sejong City: MCST.

- MCST. (2019). Motaepeondeu Munhwagyejeong Gaeyo (A Summary of Motae Fund Cultural Account).

- Morawetz, N., Hardy, J., Haslam, C., & Randle, K. (2007). Finance, policy and industrial dynamics - the rise of co-productions in the film industry. Industry and Innovation, 14(4), 421–443. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13662710701524072

- Otmazjin, N. (2011). A tail that wags the dog? Cultural industry and cultural policy in Japan and South Korea. Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis, 13(3), 307–325. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13876988.2011.565916

- Palley, T. I. (2008). Financialization: What it is and why it Matters. Düsseldorf.

- Paquet, D. (2005). The Korean film industry: 1992 to the present. In C.-Y. Shin, & J. Stringer (Eds.), New Korean Cinema (pp. 32–50). University of New York Press.

- Polanyi, K. (2001[1944]). The Great Transformation: The Political and Economic Origins of Our Time. Beacon.

- Ryoo, W., & Jin, D. Y. (2020). Cultural politics in the South Korean cultural industries: Confrontations between state-developmentalism and neoliberalism. International Journal of Cultural Policy, 26(1), 31–45. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10286632.2018.1429422

- Sawyer, M. (2013). What is financialization? International Journal of Political Economy, 42(4), 5–18. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2753/IJP0891-1916420401

- Van der Zwan, N. (2014). Making sense of financialization. Scio-Economic Review, 12(1), 99–129. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/ser/mwt020

- Vercelli, A. (2019). Finance and Democracy: Towards a Sustainable Financial System. Palgrave.

- Vestheim, G. (2012). Cultural policymaking: Negotiations in an overlapping zone between culture, politics and money. International Journal of Cultural Policy, 18(5), 530–544. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10286632.2012.708862

- Walkley, S. (2018). Cultural diversity in the French film industry: Defending the cultural exception in a digital age. Palgrave Macmillan.

- White, G. (ed.). (1988). Developmental States in East Asia. Macmillan.

- Woo-Cumings, M. (ed.). (1999). The Developmental State. Cornell University Press.

- Yonhap News. (2018). Munchebu chulja motaepeondeu suingnyul −28% yeonghwaeman tuja jipjung (The cultural ministry-sponsored Motae Fund’s profit rate: −28% … Investment concentrated on film).