ABSTRACT

In democratic societies, the political process ultimately is about making value judgements. Comparative cultural policy research indicates different value orientations may be behind cultural policies of different nations. It has also indicated developments that are common, such as democratisation of culture, neoliberalisation of politics and globalisation. As of yet, such value changes have not been studied at the level of cultural policy documents analysed as text. This article proposes a methodology to study value changes behind cultural policies over time and across nations. Based in the “pragmatic sociology” of Boltanski, Thévenot, and Chiapello, the article presents a big data methodology to uncover value changes of policy documents over time, between different policy agents, and across nations using material from the UK and the Netherlands. The paper explains the methodology, discusses the implications of the preliminary outcomes and provides suggestions for further comparative policy analyses.

Introduction

Public cultural policies are reflections of how a nation conceptualises culture and the role of the state towards this field. The differing histories and cultures of nation states have generated a wide variety of policy objectives and policy institutions that may not easily be compared (Dubois, Citation2015; Mulcahy, Citation2017; Rubio Arostegui & Rius-Ulldemolins, Citation2020). Some researchers have tried to conceptualise such differences using ideal types or archetypes (Rosenstein, Citation2019) of how cultural policies are conducted. Models for the organisation of cultural policies were introduced by Hillman-Chartrand and McCaughey in 1989, having gained a classic status in the field (Edelman et al., Citation2017, p. 131). While the models still aptly may describe how decisions regarding subsidy allocations are organised, the corresponding value orientations of each model, e.g. the Patron State’s focus on artistic excellence or the Architect State’s focus on career structure of artists, may no longer be valid. Mulcahy’s (Citation2017) more recent categorisation of policy traditions focuses on how the relation of the state to culture is conceptualised, implying each tradition comes with its own particular set of values.

Value orientations of cultural policies have also been impacted by varying policy legitimisation rationales. Most cultural policies in Western Europe, e.g., started from an elitist perspective, arguing the best of art and culture needed to be distributed for the enlightenment of the population. The 1960s and 1970s saw a shift towards a more democratic conception of culture, leading to the incorporation of the culture of the working class and (later) ethnic minorities in cultural policies. (Dubois, Citation2015). Elitism thus was complemented with democratic values. Various authors (e.g. Belfiore, Citation2004; Bell & Oakley, Citation2014; Myerscough, Citation1988; Van den Hoogen, Citation2010) point to the inclusion of economic legitimisation for cultural policies, for example, in response to the economic decline of the early 1980s, and later on during the early 2000s when a link between cultural policies and creative industries was established. The New Labour governments of the 1990s in the UK are emblematic of a focus on culture as an instrument for social inclusion, a focus we also find elsewhere (Belfiore, Citation2002). Neoliberalisation of public policies and the related trend of evidence-based policies, further skewed cultural policies towards market rationales and objectification of outcomes through statistics (see Belfiore, Citation2004; Van den Hoogen, Citation2010 for analyses of such developments in the United Kingdom and the Netherlands). Such changes in policy legitimisation should not be regarded as seismic shifts but rather as sedimentary developments that add layers of policy goals and policy instruments to policy systems (Dubois, Citation2015). Some of these values may align with the value orientations of agents in cultural or artistic fields, others may not be particularly congruent with them (Alexander, Citation2018; Edelman et al., Citation2017). In this paper, we aim to analyse how quantitative analyses of policy texts may help to uncover such valueFootnote1 changes over time and across nations by analysing cultural policy as text (Bell & Oakley, Citation2014). It presents a methodology to uncover value differences based on the pragmatic value sociology of Boltanski, Thévenot, and Chiapello (Citation2005, Citation2006). Comparative analysis then, can be conducted on three different levels:

Changes in policies over time. If documents spanning a longer period are researched, changes in value orientations over time can be traced.

Differences between policy agents within one system, for example, between a ministry and an independent policy advisor, or between arts councils of different subnational authorities.

Differences between nations. This is the most exploratory part of the research. Our aim here is to investigate whether the proposed methodology indeed yields reliable information on differences between nation states, reflecting the different value orientations their cultural policies may have.

We embarked on an exploratory research project to test the suitability of the methodology for comparative analyses of cultural policies between the Netherlands and the UK. We chose the Netherlands because its cultural policies have been clearly impacted by neoliberalisation and globalisation (Van Meerkerk & Van den Hoogen, Citation2018). Moreover, we could make use of the existing quantitative research data generated by Van den Hoogen and Jonker (Citation2018), also reported in Van den Hoogen (Citation2020), which encompass studies that developed the method used here as well. For the UK, we generated new quantitative data (see below under Methodology). The choice for the UK was instigated by four factors:

The mastery of the English language by both researchers, although neither are native speakers of the language.Footnote2

The fact that particularly in the UK, the debate on the instrumentalisation of cultural policies has been strong, as it has been in the Netherlands.

The devolution of cultural policies to the subnational authorities allows for comparison within the nation.

Both countries belong to a different tradition in Mulcahy’s terms: the UK is an example of the Mulcahy’s (Citation2017) Laissez-Faire tradition defining the arts as an inherently private matter granting a relatively limited role for the state, while the Netherlands belongs to his Social-Democratic tradition that sees art and culture as a means for personal development and hence access to culture is a major policy concern. We must recognise, however, that the Netherlands also demonstrates some tendencies towards the Laissez-Faire tradition (Van Meerkerk & Van den Hoogen, Citation2018).

Research methodology

The methodology for this research project is inspired by Luc Boltanski and Laurent Thévenot’s book titled On Justification: Economies of Worth (Citation2006, originally published in French in 1991). At the heart of their theory is the idea that there are six “economies of worth” or value regimes, which are basic structures of value used by people to reason and justify their actions. More specifically, Boltanski and Thévenot argue that a certain principle of order is present in each regime. This principle of order postulates what is fair and legitimate according to the values of that regime. While usually, only a few regimes are relevant in a particular situation, the six different regimes can be mutually present in any social interaction. The different regimes are modelled on Boltanski and Thévenot’s study of classical texts from political philosophy, in which they investigated how these texts present statements of judgement or justification. An additional regime was added to this list by Boltanski and Eve Chiapello in order to represent new developments in management strategies (Boltanski & Chiapello, Citation2005). As several value regimes can simultaneously be present in a situation, that is, a text or speech, clashes between regimes are common. Conflicts may arise when two agents partaking in the same social situation refer to different value regimes. When this happens, a compromise between the values may be achieved. Alternatively, one regime might take precedence over another one. In other words, multiple value regimes can coexist in any given situation, but they may not be equally powerful. Studying the prevalence of value regimes in certain situations and societies can expose the underlying principles of worth and distribution in connection to the idea of a common good in that society and situation.

Below, the value regimes as applied to the art world are briefly explained:

The inspired regime values inspiration, creativity, and religion and can thus be “associated with artistic autonomy such as quality [both in terms of] the quality of the work and the nature of the experience it affords” (Van den Hoogen & Jonker, Citation2018, p. 109). Artworks and prophecies are the primary products of this regime, which are valued because they are conceived of as products of personal investment. Artists and prophets produce them by being in touch with the mystical and the profound (Edelman et al., Citation2017, p. 69).

The domestic regime values concepts such as home and the family. It also incorporates a strong pattern of hierarchy, in which the old are valued over the young, and the male over the female. Of course, tradition, heritage and politeness are held in high esteem, whereas innovation and spontaneity have low value. For example, “heritage and the use of old aesthetic languages in the arts represent domestic values” (Van den Hoogen & Jonker, Citation2018, p. 109).

The regime of fame values public opinion, which means that recognition and reputation are very important. Gossip and rumours are tools of communication and are considered helpful. As such, the regime “revolves around press attention, public meetings and public relations” (Van den Hoogen & Jonker, Citation2018, p. 109). Consequently, journalists, press agents and celebrities are important figures in this regime in the context of the arts.

The civic regime is based on the notion of the “general interest”. Democratic processes, such as group consent, are therefore, highly valued. Unsurprisingly, in parliamentary democracies, any public policy requires reference to civic values (Edelman et al., Citation2017). Further, civic leaders act as representatives for subgroups or even society as a whole. This value regime stresses the importance of collective interests as opposed to individual gains.

The market regime is focused on principles of competition, rivalry and profit. Money and the possession of luxury goods are measures of success (Van den Hoogen & Jonker, Citation2018, p. 109). Opportunism is conceived of as good quality, as it is associated with the idea that a subject is capable of seising the right moment to engage in activities of buying and selling. The market regime is often at odds with the inspired regime, as it attaches no values to individuals or that which cannot be owned, for example, an experience (Edelman et al., Citation2017).

The industrial regime values efficacy and efficiency. As such, this regime stresses the importance of knowledge and experts (Van den Hoogen & Jonker, Citation2018, p. 109), it is future-oriented and aims for improvements. Expertise is conceived of as a form of reliability needed for development, and therefore, an industrial value. Consequently, processes must be standardised, predictable and evaluated regularly. In fact, the industrial regime is often at odds with the inspired regime, because of the unpredictability of live performances, for example. However, it should also be noted that the art world too has many industrial qualities, as it is also a professional industry and, therefore, features certain standards in its education or performance, for example. Artistry itself is a form of expertise.

The seventh regime, the project regime, values flexibility, contacts and cooperation. Indeed, it “is a project-based regime, focusing on the ability of agents to move from one project to the next” (Van den Hoogen & Jonker, Citation2018, p. 109). Both an individual’s ability to adapt quickly to new situations as well as the ability to assemble individuals with the required skills for specific situations are highly valued (Edelman et al., Citation2017). Hence, this regime can be understood to be a compromise between the inspired, market and industrial regimes. It is, therefore, not a “pure” value regime and can rather be considered as a “hybrid”, which makes it difficult to operationalise this regime in the present study. While in some studies using this methodology, the project regime is omitted for quantitative analyses (Van Winkel et al., Citation2012), we opted to give the regime a specific meaning (see below).

The values employed are always context-specific and depend on an interplay of situation and subjects involved. In other words, value regimes are not absolute. Some values, such as values from the inspired regime and the domestic regime, are more intrinsic to the art world and are, therefore, more readily associated with art and heritage. In fact, Boltanski and Thévenot make extensive use of the art world to explain the inspirational regime. On the other hand, other values, such as those from the industrial regime and the market regime, are more oriented towards efficiency. They are, therefore, closely related to managerial values that may not always align with artistic interests (Alexander, Citation2018). They may also reflect the economic instrumentalizations of cultural policies.

The theory is used to analyse texts from concrete cultural policy systems. We here closely follow Boltanski and Thévenot’s original strategy that analyses texts from political philosophy and management handbooks quantitatively using lists of words belonging to a particular regime or to two regimes in the case of compromise words. They provide lists of nouns and verbs for each regime as these refer to actions discussed (verbs) and objects and subjects that are deemed important (nouns). The present study also includes adjectives because they are frequently used to express evaluations, for example, in subsidy allocation decisions. Van den Hoogen and Jonker (Citation2018) thus developed a word list for the Dutch study that was translated into English to allow for a comparison across the two nations. A complete list with all words categorised can be found in Appendix 1. An example of compromise words is “subsidy”, as it belongs both to the market and civic regimes. In a civic context, “subsidy” refers to the money a government grants an organisation, which generally acts on behalf of the general interest. Additionally, “subsidy” in a market context simply refers to money. In such a case, the document classifier we used (see below) counts the word twice, one time for each category it belongs to. However, when in policy documents, the word “subsidy” is replaced by “investment”, this is a shift towards a more market-oriented approach (Belfiore, Citation2004) that becomes visible in the word count as “investment” belongs to the market regime only.

The actual analysis is performed using a document classifier, which is a specifically designed computer programme. First, we set up a project folder including the relevant policy documents we included in our corpus (see below under Corpus). Next, we added the word lists for every value regime to the programme. The document classifier turned the policy documents from pdf versions into text versions. Next, the programme removed punctuation and scanned every word individually per document. The programme checked whether the individual word was present in one of the word lists. If the word did not yet occur in any of the lists, the programme notified the researcher and the word had to be assigned to a category manually.

In total, we created nine categories, which consist of seven categories for the different value regimes, as well as a “discard” and “discuss” category. The “discard” category includes words such as stop-words, pronouns and numbers that do not add any meaning to the text in terms of the categories that we were analysing. Other information, such as page numbers and the colophon, were also registered in the “discard” category. Sometimes, a specific word was used in various contexts across the texts we examined. In these cases, the word was added to the “discard” category, simply because it was too generic to belong to one or more value regimes. An example of this is any variation of the verbs “to be” or “to have”. In this way, we were able to navigate the ambiguity inherent in the language in general. Because we discarded words that are too generic in their meaning and analysed the remaining words according to the value regimes, we were able to provide a framework for the language used in the context that is consistent across all documents analysed.

In this methodology, the key decision is how words are assigned to the regimes. We cannot provide a full explanation of why each word is assigned to a regime. Below, we provide an indication of frequent words in each regime.

Words such as “art”, “life”, “experience”, “creative” and “culture” were assigned to the inspired regime as they represent the nature of artistic work.

Words such as “history”, “family”, “values”, “heritage” and “generations” relate to history and ancestry and are, therefore, domestic. We also counted all references to specific locations (e.g. Wales) in this regime as art objects may be rooted in local or regional languages or traditions.

Words such as “recognize”, “priority”, “celebrate”, “media”, “important” and “promote” point to public attention and, therefore, are counted in the fame regime.

Words such as “people”, “workforce”, “policy” and “community” represent collective entities or collective action and, therefore, are counted in the civic regime.

Words such as “money”, “achievement”, “economy”, “funding” and “workforce” refer to economic issues and success and are, therefore, counted in the market regime.

Words such as “building”, “increase”, “sustainable”, “sectors”, “effectively”, “support” and “thrive” represent industrial logic, including means that serve a particular end.

Words such as “exchange”, “collaboration”, “shared”, “connections” and “relations” were counted in the project city regime as in our research, this regime was used to represent logic concerning how cultural institutions make connections to their environment, which has been a particular concern in Dutch cultural policies.

We used the “discuss” category for words that were ambiguous as to which value regime they belong to. In order to decide whether these words should be discarded or assigned to one or more value regimes, we paid close attention to these words’ contexts. In doing this, we made informed decisions about which category these words belong to. If a careful assessment of the context of the word in question would demonstrate that it belongs to several categories simultaneously, the word was added to the word lists of these categories. Finally, the document classifier generated a list containing every word that occurred per category in each text. From this, we could defer the number of words per value regime across the corpus, and of course, also identify how many times a specific word occurred in a given text. This type of information allowed us to calculate the relative presence of each value regime per text.

Corpus

This paper presents an analysis of cultural policy documents of the Netherlands and the UK. These countries have quite different policy systems, the former based in the Architect Model (Hillman-Chartrand & McCaughey, Citation1989) with a central ministry granting subsidies directly to cultural institutions informed by independent policy advice, and the latter based in the Patron State, with central arts councils allocating subsidies to institutions.Footnote3 As a result, the types of policy documents produced by these systems differ.

In the Dutch case, a clear distinction can be made between policy documents written by the Ministry and the policy advice documents written by the Council for Culture, that is, there is a difference between documents explaining policy principles and those explaining subsidy levels to individual cultural institutions. The Dutch system produces these documents on a regular basis: every four years, a policy plan and a subsidy plan are drawn up. The Dutch research, therefore, includes all policy and advisory documents produced between 1993 and 2017, spanning seven policy cycles. For the advisory documents, only those parts pertaining to the theatre (spoken theatre, dance and youth theatre) were included in the analysis.

In the UK, separate documents detailing individual subsidy allocations are not produced. We have used the strategic policy documents of the art councils, because these are available on their websites. The available documents span a period of ten years, that is, they do not allow for the same longitudinal analysis. However, the devolution of cultural policies to England, Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales allow for comparisons between these authorities. Particularly, we are interested in the Scottish situation, as the name of the arts council, Creative Scotland, seems to indicate an orientation towards the creative industries, rather than art per se, which might lead to a different value orientation. The different political situation of Northern Ireland is of interest as well, because we might expect the civic value of reconciliation to be stronger. Furthermore, in the small nations of Wales and Scotland, domestic values might be important in an effort of positioning their culture (and language) vis-à-vis the English behemoth.Footnote4

All documents included in the corpus are listed in Appendix 2.

Hypotheses

Our analysis is based on six hypotheses:

Cultural policies are essentially based on a combination of civic and inspirational regimes. This combination reflects the underlying legitimisation of cultural policies as being intrinsically good for all (Edelman et al., Citation2017; Vestheim, Citation2007).

Evidence-based policies, over time, lead to the growing importance of the industrial regime, as evidence-based policies emphasise the importance of scientific facts and quantitative analyses.

Over time the market and possibly also fame regimes become more important as these reflect instrumentalisation of cultural policies, particularly in the economic domain.Footnote5 The civic domain may also play a role when policies are instrumentalised for social development, for example, in Northern Ireland. Both developments may come at the expense of the regimes that represent autonomous values, i.e., the inspirational regime, the industrial regime (artistic expertise) and the domestic regime (heritage).

Within the Netherlands, we expect the values of the Council for Culture to be more firmly based on the inspirational, industrial (artistic expertise) and domestic (heritage) regimes than the ministerial documents.

Within the UK, we expect different values to occur for the different subnational authorities.

We expect to find value differences between the UK and the Netherlands as their cultural policies are based on different policy traditions (Mulcahy, Citation2017).

Hypothesis I reflects a common trait of public cultural policies irrespective of which tradition or model they stem from. Hypothesis II reflects the advent of evidence-based policies and hypothesis III represents instrumentalization of cultural policies. Hypotheses IV and V reflect the different roles we expect agents within policy systems will perform and hypothesis VI reflects our initial argument that policy systems of different countries may be based on very different value orientations. Below we will first present the quantitative analysis yielded by our research method and then briefly discuss to what extent the data confirms or disproves these hypotheses.

Outcomes of the exploratory empirical research

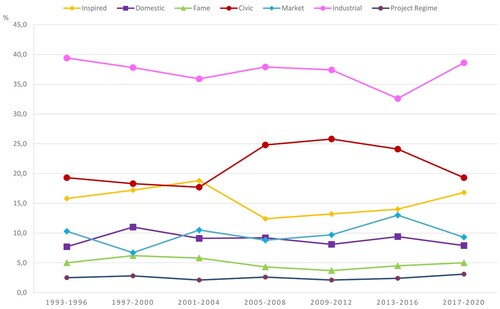

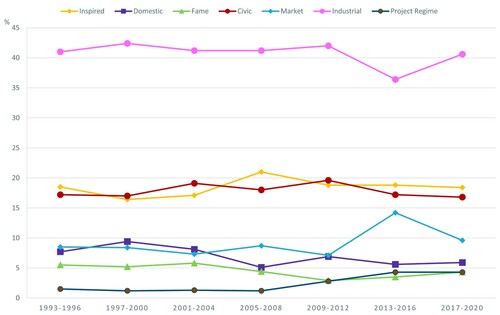

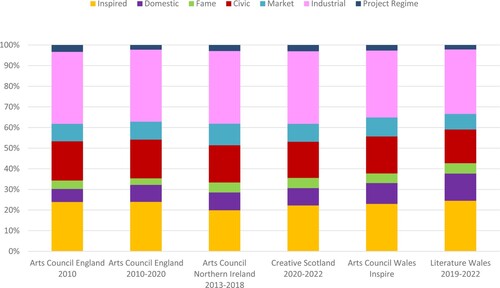

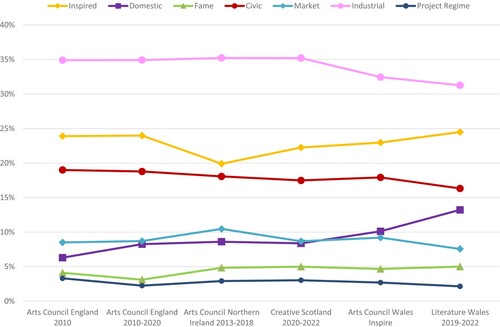

and represent the distribution of values in the Dutch policy documents (table 1) and in policy advice (table 2). and present the data for the UK research.

The most noteworthy result of the analysis is the prevalence of the industrial regime overall. For the UK data, the percentage of the industrial regime ranges around 30% for each individual arts council document, whereas in the Netherlands, this percentage is even higher, around and even above 40%. The fact that the industrial regime outweighs all of the other regimes can be explained by a number of factors. First, policy plans and strategies are indeed industrial phenomena, because they are a plan of action to achieve a certain goal. More specifically, the analysed documents are purposefully written to communicate these strategies and describe and justify cultural policy goals and procedures. Particularly, the documents by the Council for Culture elaborately explain such procedures. This is necessary because the advice provided by the Council is basically the legitimisation of individual subsidy allocations that are open to appeal in court (Van der Vlies, Citation2018). The important issue to note here is that while the policy goals as such may not be industrial, policy-implementation procedures certainly are. For this reason, it is no surprise that industrial language is extensively used in these documents.

Further, a considerable number of words that certainly belong to the industrial regime are used to refer to artistic processes. A good example is the word “performance”, which belongs to both the industrial and the inspired regimes. It is a reference to an artistic product, but performance is also a means to an end, for example, when through tours productions reach larger audiences, serving policies aimed at access to culture. Finally, we heavily rely on industrial language in our vernacular language. It is not surprising to find traces of the kind of language people use in their daily lives in documents that are written for a broad and inclusive audience. Words that are frequently used and belong to the industrial regime are, for example, “years”, “investment”, “development”, “skills”, “support” and “working”. As a consequence, these words also received a high count in all of the documents.

The second and third positions belong to the inspired and civic regimes, respectively. This corroborates hypothesis I. However, there are two instances in which a deviation becomes apparent: (1) in the Dutch data for the policy period 2013–2016, both in the policy documents and in the advice, the market regime is almost as prominent as the inspired/civic compromise and (2) for the Arts Council of Northern Ireland, the inspired regime loses importance in favour of the market regime.

The fourth and fifth positions are held by the market and domestic regime. Interestingly, these regimes are evenly distributed across all of the documents, with the exception of the documents by the arts council of Wales and Literature Wales, in which the domestic regime takes precedence over the market regime. This is especially interesting in the document of Literature Wales, where the domestic regime’s precedence is characterised by a much bigger margin. This can be explained by the Welsh government and the Arts Council’s focus on Welsh national language and heritage, which can be categorised as domestic values (see below under hypothesis V). In the case of Literature Wales, it can be noted that the increase of the domestic world comes at the expense of the market regime.

The sixth and seventh positions are held by the fame and project regimes. As mentioned above, the project regime is difficult to utilise in quantitative analysis. We, however, opted to give it a specific meaning: how art organisations make connections to their environment. Apparently, this has become a more important issue in Dutch cultural policy, as there has been a steady rise of this regime in the previous policy periods. This is represented by the policy that pays attention to the relation between nationally-funded institutions and local audiences and infrastructures. Although the distribution of National Portfolio Organisations across the country and attention to underfunded areas have been prominent policy issues, particularly in England, the UK data does not represent a similar rise in the importance of this value regime.

Hypotheses I and VI: the basic value orientations of cultural policies in the Netherlands and the UK

As predicted, the inspirational and civic value regimes turn out to be of central importance to cultural policy, both in the Netherlands and in the UK. Moreover, there does not seem to be a large difference in the relative weight of the other regimes. All in all, the results are very comparable, which leads us to conclude that though policy systems indeed may be based in different traditions and organisational forms, on the level of policy texts, their value orientations concur. However, the conclusion cannot be definite here for two reasons. First, if we were to take longer time frames into account, we might find different value orientations. Second, if we were to consider different countries, for example, the Scandinavian countries that seem to be far more firmly based in Mulcahy’s Social-Democratic tradition than a mercantile nation such as the Netherlands that also presents traces of the Laissez-Faire tradition, the data might present different value orientations.

On a more detailed level, we do find a small difference: in the Netherlands, the civic regime seems to hold somewhat more sway in the policy documents. This is logical as the analysed documents are produced by the ministry itself. Also, the Dutch advisory documents point to a more prominent position of the civic regime, as the civic regime ranks higher than the inspirational one in three out of seven policy periods. In the UK, the inspirational regime trumps the civic one in all documents. Apparently, the art councils have more leeway in focussing on inspirational values than the Dutch system, with a larger role for the ministry.Footnote6

Hypothesis II: growing importance of the industrial regime

As the industrial regime scores highest throughout the full periods researched, the data of this research does not confirm the assumption that evidence-based policies have led to a rise in industrial values at the expense of intrinsic values. The hypothesis must be rejected based on this data. Either, both the UK and the Netherlands have always been very goal-oriented, and evidence-based policies are quite “natural” to these two nations or the research method is not sensitive enough to demonstrate the value changes indicated by Van den Hoogen and Jonker (Citation2018), who in the qualitative part of their research did find a rise of industrial values over time.

Hypothesis III: instrumentalisation of cultural policies

The Dutch data do represent this trend to some extent. The rise of the market regime can be seen as indicative of this trend, particularly for the 2013–2016 period, where the market regime almost reaches the level of the crucial civic and inspirational compromise that is at the core of policy legitimisation. This is the policy period that introduced a budget cut of circa 20% to the national budget for culture. The cuts were legitimised by pointing to the “overreliance” of the cultural sector on subsidies and their meagre orientation towards the market. More stringent management and marketing criteria were introduced to the system, and they exist to date. In the advisory documents, market values, therefore, also become more important, although, in the most recent policy period, market values do recede in importance. However, they still occur at a higher level than before the policy period of 2013–2016.

The UK data does not allow for conclusions on this hypothesis. However, as the value patterns found for the arts councils in the UK and for the Dutch Council for Culture seem to be fairly consistent, we can conclude that the instrumentalisation of cultural policies does not fundamentally impact the value orientations in policy advice. The position of independent policy advisors in cultural policy systems is, therefore crucial, as they seem to be able to mitigate pressures from the policy system. However, it should be indicated that while the impact of politics on policy advice, particularly on individual subsidy allocations, may be limited, their impact on the system as a whole is fundamental, as politics determines the total public budget available for arts and culture. This point, albeit outside of the scope of this research project, is certainly important to highlight in connection to research on values in cultural policy more generally.

Hypothesis IV: differences between ministry and advisor in the Netherlands

While the policy documents demonstrate quite erratic value patterns (), the value pattern in the Council for Culture documents (), that is, the documents that legitimise actual subsidy allocations for theatre in the Netherlands, appear to be based in a fairly stable set of values. Again, this indicates the possibility of independent advisors to mitigate pressures from the political system to the cultural system.

Hypothesis V: differences between subnational authorities in the UK

Interestingly, the data presented here do not indicate different value orientations between the different subnational authorities in the UK. The documents of Creative Scotland are not more firmly based in the market regime, nor is the Northern-Irish document more firmly based in the civic regime. However, we do see more focus on the domestic regime in the documents of the art council of Wales, particularly Literature Wales, as it presents a document devoted to a sector firmly based on language.

Advantages and disadvantages of automated word count

In this closing section, we will discuss the advantages and disadvantages of the method and suggest further steps for comparative research.

One of the most apparent advantages of this automated method is the time saved by not having to assign every word per text individually to one of the categories. Instead, we only had to assign every word across the whole corpus of texts to one or more categories once. Not only did this save a great deal of time but also tremendously lowered the chances of miscounting and/or assigning words to the wrong category, while also limiting the possibilities for human error. This also allows the researchers to distance themselves from the text, which, too, provides consistency and continuity. Further, management of each category is easy as the world list are easy to manipulate, facilitating comparative research and allowing for large quantities of text to be analysed quickly. Also, new texts (e.g. from a new policy period) can be added to the existing analysis. However, the automated method also presents disadvantages.

First, the document classifier did not immediately function properly, and some mistakes only become apparent when performing the analysis, requiring some reprogramming. Also, the process of converting policy documents to PDF’s did not always go smoothly, which required considerable manual correction of the text files (for example, the programme would fail to register the letters “fi” before a word, misspelling them in the text file). Overall, however, the total workload was reduced because of the document classifier.

An additional issue we encountered frequently was word ambiguity. Of course, words may have various meanings that can change according to the context in which they appear. For example, the word “will” can have different meanings, depending on whether it operates as a verb or a noun. To solve this problem, as explained above, such ambiguous words were assigned to the discard category. Also, some words that are particular to the cultural field can have multiple meanings. This occurred in the Dutch data. For example, the word “composition” (compositie in Dutch) in this research has been assigned to the inspirational value regime, as it refers to a piece of music, ergo it is an artistic reference. However, when the composition of audiences is indicated, the meaning of the text refers to audience reach, which is a civic value.Footnote7 For such phrases, the document classifier will score both words “composition” and “audience”, i.e., both the inspirational and civic regimes. This situation is unavoidable. As long as the occurrence of such mistakes is relatively small when compared to the total number of words assigned and the mistake is made consistently, it does not invalidate the outcomes of the analysis. Therefore, the relative weight of value regimes over time presents the most important outcome of the research, not the absolute number of occurrences of words.

Some other measures enhanced the validity of the research. Assigning words to a category was done by multiple researchers. In the Dutch research, in total, four researchers were involved in checking the assigning of words in three rounds. All researchers were familiar with the Dutch policy system, and two had hands-on experience in handling subsidy allocation decisions. The UK data was processed by the two authors of this paper, one of them was part of the team for the Dutch research. In order to secure consistency between the analysis of both data sets, the word lists of the Dutch research were used as a basis of the UK analysis, although it is a notable limitation that no researchers who are familiar with the UK system itself were involved. Furthermore, triangulation of the research outcomes enhances reliability. In the original Dutch research, the quantitative analysis was accompanied by a series of interviews with officials from the Council for Culture (see Van den Hoogen & Jonker, Citation2018) that confirmed the prominent position of the industrial regime and the changes regarding the market regime. The prominent position of the industrial regime in the UK data conforms with earlier research that demonstrates how evidence-based policies have impacted on UK cultural policies (e.g. Belfiore, Citation2004). However, further triangulation with more in-depth analyses of policy documents is necessary and should be part of comparative analyses using quantitative methods such as these. Combining them with interviews of policy officials and/or in-depth content analysis of a selection of the policy documents is necessary, first to check reliability of the quantitative outcomes and, second, to contextualise changes in value orientations. The quantitative analysis can only indicate broad value changes over time, it cannot indicate why they occur and how.

A final issue concerns the differences between languages. As this methodology depends on language use, the method is vulnerable to cultural differences between national languages used in policy text. We, for instance, feared that the occurrence of composite words would compromise our research outcomes. They are treated differently in the Dutch and English language. While a composite term, such as “theatre company” in the English language, is written as two words, the document classifier will classify them separately (in the inspirational regime for theatre and the industrial for company). In Dutch, it is one word (theatergezelschap). As in the Dutch research, such composite words were scored twice based on the meaning of each part of the word (again both inspirational and industrial), this language difference did not impact our research outcomes, allowing for comparison of the data. A more prominent problem, however, resulted from the fact that we as non-native speakers of the English language, were not always able to identify subtle differences in meanings of words in the English language. Therefore, for future – more elaborate – comparative analyses, it is vital that native speakers of the language used in the policy documents conduct the research. Moreover, such native speakers will be aware of the organisational features of the cultural policy systems under scrutiny. For example, while there are many different countries in the world that use English as their first and official language, it might be worthwhile considering whether an English native speaker from England would be as competent to perform this kind of research on Australian policy documents as a native Australian, and vice versa. This will aid in choosing a correct corpus of texts for analysis and correct assignments of words. The discuss category will allow different researchers to work independently on the texts generated by their policy system, compiling a list of words that need collaborative decisions on how to assign them. As such, comparative research between nations should be feasible. Therefore, this article should be primarily read as an invitation to those native speaker researchers to use the methodology presented here in order to develop comparable research data across nations.

Value for comparative policy analysis

What new insights can this type of quantitative analysis yield for comparative policy research? Does it indeed produce new insights? We come to a mixed conclusion. On the one hand, the fact that in both policy systems – as expected – the central value perspectives stem from the inspirational and civic regimes indicate that even though instrumentalisation and neoliberalisation may have impacted on cultural policies, they are still dominated by the two most “appropriate” regimes. Laments as to the negative impacts of instrumentalisation are not supported by this data. The extent to which similar value patterns occur are, however, striking given the assumption of differences between national systems. On the one hand, this may point to the impact of general trends in cultural policies such as have been indicated in the introduction. On the other hand, this outcome may be the result of the choice of our corpus. We have limited the research to quite generic policy documents in both systems. If we were to choose more particular types of texts, such as white papers on a particular issue (international cultural collaboration, inclusion of ethnic minorities, or youth culture); public speeches by politicians or officials; subsidy allocation decisions; political party programmes; or minutes of parliamentary debates, the analysis might elucidate more subtle differences in value orientations, between different agents in the policy systems and across nations. Choosing other than formal policy texts may also solve the issue that this type of analysis skews comparative policy analysis to formal systems that tend to produce written policy documents on a regular basis.

Furthermore, we could imagine using a more subtle “grid” than Boltanski and Thévenot’s classification of only seven, quite generic, regimes. For instance, when analysing how artistic quality is defined and assessed in different systems or different art forms, the inspired regime might be “opened up” for distinguishing between situations where quality is linked to authenticity or to novelty and experimentation of form, to development of styles (giving it domestic connotations) or to technical abilities of makers (giving it industrial connotations). Alternatively, it could be worth investigating whether, within the industrial regime, it is possible to distinguish between words that relate to procedures for making policy decisions and applying for subsidies, and artistic standards or working methods. Currently, such diverse issues are conflated in a single regime. In other words, future research might use a more sophisticated “grid” of values than the seven original regimes. Such research might provide a quantitative follow-up from qualitative research that may have yielded categories that are relevant for the investigation, allowing for firmer conclusions on the relative weight of such categories in concrete policy situations.

Of course, the premise of this type of research method is that the policy systems under scrutiny actually operate on the basis of their written texts, which may not always be the case. Nonetheless, we hope this expose of preliminary research outcomes will spark interest in this type of comparative analysis.

Acknowledgements

We want to acknowledge the invaluable contribution of Travis Hammond to this research project. He developed the document classifier that was used to conduct the empirical analysis. The document classifier can be downloaded from: https://github.com/dashdeckers/DocumentAnalyzer. This website also contains an installation and user manual. The document classifier is designed to handle texts in English and a variety of European languages.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 In this introduction, we have used the word “value” in a somewhat pragmatic way, indicating general values such as democracy, equality, excellence and prosperity but also denoting particular goals of cultural policies such as social inclusion, economic benefits or image of the nation, that may be derived from such more generic values. In this research we focus on the notion of value regimes as presented by Boltanski and Chiapello (Citation2006) rather than values.

2 As one of the researchers is a German native, we originally set out to conduct a comparative analysis between Germany and the Netherlands. This would have allowed a comparison between a policy tradition based in Mulcahy’s Cultural States tradition (Germany) and a Social-democratic tradition (the Netherlands). However, as the German cultural policy system is fully local, mostly based in the Engineer State model (Hillman-Chartrand & McCaughey, Citation1989), the system does not generate policy texts and hence turned out not to be suitable for the type of analysis envisioned.

3 As of 2009 the Dutch system actually presents a mix of the Architect and Patron State models, as the ministry allocates subsidies to the central cultural institutions in the country (Basic Infrastructure), and to five independent cultural funds that serve the role of arts council towards smaller cultural institutions.

4 Such an argument resembles Mulcahy’s (Citation2017) Protectionist tradition which he models on the Canadian nation “resisting” American influences.

5 In Boltanski and Thévenot’s regime, the market regime does not coincide with what in vernacular language is called “the market” or “the market economy”. Rather, the market economy is reflected in a number of value regimes, most notably the market regime (focusing on making deals and saleability, profit being the proof of value according to this regime), the fame regime (focusing on public attention, marketing of products being considered as a profitable strategy) and the industrial regime (focusing on cost-efficiency).

6 Indeed, the criteria that the Council for Culture applies to subsidy allocations are determined by the ministry. However, the Council does have some leeway determining how such criteria are interpreted.

7 In all texts we scored references to audience as civic as in policy discourse mentioning the audience usually is related to enlarging the reach of cultural facilities. We scored words such as “youth”, “toddlers”, “children” and “elderly” in the civic regime as well as in policy documents these usually indicate particular audience segments.

References

- Alexander, V. D. (2018). Heteronomy in the arts field: State funding and British arts organizations. The British Journal of Sociology, 69(1), 23–43. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-4446.12283

- Belfiore, E. (2002). Art as a means of alleviating social exclusion: Does it really work? A critique of instrumental cultural policies and social impact studies in the UK. International Journal of Cultural Policy, 8(1), 91–106. https://doi.org/10.1080/102866302900324658

- Belfiore, E. (2004). Auditing culture; the subsidised cultural sector in the new public management. International Journal of Cultural Policy, 10(2), 183–202. https://doi.org/10.1080/10286630042000255808

- Bell, D., & Oakley, K. (2014). Cultural policy. Routledge.

- Boltanski, L., & Chiapello, E. (2005). The new spirit of capitalism. (Translated by Gregory Elliot from Le nouvel esprit du capitalisme). Gallimard Verso. (Original work published 1999)

- Boltanski, L., & Thévenot, L. (2006). On justification, economies of worth. (Translated by Catherine Porter from De la justification, Les économies de la grandeur). Gallimard & Princeton University Press. (Original work published 1991)

- Dubois, V. (2015). Cultural policy regimes in Western Europe. In J. D. Wright (Ed.), International encyclopedia of the social & behavioral sciences (pp. 460–465). Elsevier.

- Edelman, J., Hansen, L. E., & Q. L. van den Hoogen. (2017). The problem of theatrical autonomy: Analysing theatre as a social practice. Amsterdam University Press.

- Hillman-Chartrand, H., & McCaughey, C. (1989). The arm’s length principle: An international perspective. In M. C. Cummings Jr. & J. M. Davidson Shuster (Eds.), Who is to pay for the arts. The international search for models of arts support (pp. 43–79). American Council for the Arts.

- Mulcahy, K. V. (2017). Public culture, cultural identity, cultural policy comparative perspectives. Palgrave MacMillan.

- Myerscough, J. (1988). The economic importance of the arts in Britain. Policy Studies Institute.

- Rosenstein, C. (2019). Cultural policy archetypes: The bathwater and the baby. International Journal of Cultural Policy, 27(1), 16–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/10286632.2019.1691175

- Rubio Arostegui, J. A, & Rius-Ulldemolins, J. (2020). Cultural policies in the South of Europe after the global economic crisis: Is there a Southern model within the framework of European convergence? International Journal of Cultural Policy, 26(1), 16–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/10286632.2018.1429421

- Van den Hoogen, Q. L. (2010). Performing arts and the city. Municipal cultural policy in the brave new world of evidence-based policy (PhD, University of Groningen).

- Van den Hoogen, Q. L. (2020). Dutch theatre politics in crisis? In T. Fisher & C. Balme (Eds.), Theatre institutions in crisis: European perspectives (pp. 93–104). Routledge.

- Van den Hoogen, Q. L., & Jonker, F. (2018). Values in cultural policy making: Political values and policy advice. In E. van Meerkerk & Q. L. van den Hoogen (Eds.), Cultural policy in the polder: 25 Years Dutch cultural policy act (pp. 107–130). Amsterdam University Press.

- Van der Vlies, I. (2018). Legal aspects of cultural policy. In E. van Meerkerk & Q. L. van den Hoogen (Eds.), Cultural policy in the polder: 25 Years Dutch cultural policy act (pp. 41–66). Amsterdam University Press.

- Van Meerkerk, E., & Van den Hoogen, Q. L. (2018). An introduction to cultural policy in the polder. In E. van Meerkerk & Q. L. van den Hoogen (Eds.), Cultural policy in the polder: 25 Years Dutch cultural policy act (pp. 11–36). Amsterdam University Press.

- Van Winkel, C., Gielen, P., & Zwaan, K. (2012). The hybrid artist: Organisation of artistic practice in the post-industrial era [De Hybride Kunstenaar: de organisatie van de artistieke praktijk in het postindustriële tijdperk]. Breda: Expertisecentrum Kunst en Vormgeving, AKV|St.Joost (Avans Hogeschool). https://www.inholland.nl/media/10709/eindrapporthybridiseringdef.pdf

- Vestheim, G. (2007). Theoretical reflections. International Journal of Cultural Policy, 13(2), 217–236. https://doi.org/10.1080/10286630701342907

Appendices

Appendix 1. Top 30 most occurring words per value regime (UK data)

Table A1. Overview of most prominent words in each value regime (UK data).

Appendix 2. List of documents included in the corpus

The Netherlands

Policy documents (Ministry for Education, Culture and Sciences, the first document: Ministry for Welfare, Health and Culture):

Investeren in Cultuur: Nota Cultuurbeleid 1993–1996 [Investing in culture].

Pantser of Ruggengraad: Uitgangspunten voor Cultuurbeleid 1997–2000 [Armour or backbone: Principles for cultural policy 1997–2000].

Cultuur Als Confrontatie: Uitgangspunten voor het Cultuurbeleid 2001–2004 [Culture as confrontation: Principles for cultural policy 2001–2004].

Meer dan de Som: Beleidsbrief Cultuur 2005–2008 [More than the sum. Policy brief culture 2005–2008].

Adviesaanvraag Basisinfrastructuur 2009–2012 [Request for advice on base infrastructure 2009–2012].

Meer dan Kwaliteit. Uitgangspunten Cultuurbeleid 2013–2016 [More than quality. Principles for cultural policy 2013–2016].

Ruimte voor cultuur. Uitgangspunten Cultuurbeleid 2017–2020 [Space for culture. Principles for cultural policy 2017–2020].

Documents council for culture (until 1995 Council for the arts)

Advies kunstenplan 1993–1996 [Advice for the arts plan 1993–1996], general part (p. 19–36) and sections on theatre and dance.

Een Cultuur van Verandering: Advies Cultuurnota 1997–2000 [A culture of change: Advice for cultural policy 1997–2000], theatre and dance part.

Van de Schaarste Ende Overvloed: Advies Cultuurnota 2001/2004 [On scarcity and abundance. Advice for cultural policy 2001–2004], theatre and dance part.

Spiegel van de Cultuur: Advies Cultuurbeleid 2005–2008 [Mirror of culture: advice for cultural policy 2005–2008], parts 7 (Dance) and 9 (Theatre).

Basisinfrastructuur 1.0 Advies vierjaarlijkse cultuursubsidies voor instellingen, sectorinstituten en fondsen in de Basisinfrastructuur [Advice for cultural base infrastructure 2009–2012], p. 451–603 (performing arts).

Slagen in Cultuur: culturele basisinfrastructuur 2013–2016 [Succeeding in culture. Cultural base infrastructure 2013–2016], p. 36–130 (Theatre, youth theatre, dance and festivals).

Advies Culturele Basisinfrastructuur 2017–2020 [Advice for cultural base infrastructure 2017–2020], Theatre, youth theatre, festivals, production houses and dance.

United Kingdom

Arts Council England. 2010. “Achieving great art for everyone – a strategic framework for the arts”.

Arts Council England. 2013. “Great art and culture for everyone – 10 year strategic framework”.

Arts Council Northern Ireland. “Ambitions for the arts: A five year strategic plan for the arts in Northern Ireland 2013–2018”.

Arts Council of Wales. “Inspire … Our strategy for creativity and the arts in Wales”.

Creative Scotland. 2014. “Unlocking potential embracing ambition – a shared plan for the arts, screen and creative industries 2014–2024”.

Literature Wales. 2019. “Strategic plan 2019–2022”.