ABSTRACT

Decolonising the curriculum is a global imperative that takes different forms and urgency depending on the context. Developments across the globe such as BlackLivesMatter and student responses to the pandemic and online learning have raised new questions about the curriculum – critically questioning higher education institutions’ plans about not only providing access to resources but about the (cultural) authority of curricula, pedagogical and research practices that are still dominated by Western discourses. This paper examines three experiences of curriculum decolonisation in cultural policy and management, an applied subject that has culture as its object, in three different contexts, Serbia, Puerto Rico and South Africa: namely how the pursuit of a pluriversal knowledge ecology found expression in the curriculum, content and pedagogical practices deployed to deliver locally relevant education; and how educators resolved the ontological and epistemic discontinuities between the standard disciplinary canon and local realities to embed and contextualise the discipline.

Introduction

Decolonising the curriculum is a global imperative that takes different forms and urgency depending on the context. Developments across the globe such as BlackLivesMatter, student responses to the pandemic and online learning have raised new and similar questions about the curriculum – critically questioning higher education institutions’ plans to migrate the academic programme online and suggesting that it was not only about providing access to resources, but also about the (cultural and moral) authority of curricula, pedagogical and research practices that are still dominated by Western discourses.

We follow this lead. In this paper, we focus on three different contexts from Serbia, in the semi periphery of Europe, Puerto Rico, South Africa on the southern tip of the African continent. All four authors have been directly involved in restructuring curricula in their schools, acting as academic activists: opening controversial issues and creating platforms for North–South research dialogues. At the same time, the authors were mutually collaborating through UNESCO programmes, ENCATC and other scholarly networks.

In South Africa, since democracy began in 1994, transformation has been an ongoing project with calls for Africanisation and indigenisation, and, more universally, since the #FMF movement, about decolonising the curriculum as well as the university. Decolonisation gained urgency since #RhodesMustFall began in early 2015. It was a huge rupture in the symbolic understandings of the university which continued through #FeesMustFall and #EndOutsourcing in 2015 and 2016 and the response of some students and academics to emergency remote teaching during the pandemic. In many respects, it was challenging the universities to adopt a decolonial response to the pandemic. In this way, decolonisation has become an urgent “exciting” and daunting “impetus for praxis” in South Africa.

Serbia, in the Balkans, was colonised from the East, by Ottoman Turkey in the fifteenth century though Balkan self-liberation in the nineteenth century was followed by “self-colonisation” by Western knowledge (Kiossev, Citation1995), sending into oblivion not only Ottoman heritage, but also the traditions and knowledge legacies of Greek (Byzantine), Serbian, Bulgarian and Romanian medieval states. So, the Byzantine history and culture erased from memory by Ottoman rule have yet to find place in Balkan national curricula. The creation of Yugoslavia in 1918 commanded further Westernisation, seen as progress, emancipation and enlightenment. After 1945 a Yugoslav socialist regime emerged (distinct from Soviet socialism).

The 1990s breakup of Yugoslavia, the inter-ethnic wars, embargo, inflation, media manipulation and autocratic rule divided society, creating social and value conflicts – prompting the rejection of socialist values but also unwillingness to accept capitalism, perceived as Western values. Hence the numerous efforts at rewriting history and creating new national narratives, mostly in the political and media spheres. Still, university autonomy prevented radical nationalist “revision” of knowledge and curricula. After 2001, society faced crucial but conflicting questions: valuing the local knowledge created during socialism (in the nineties rejected as “communist” or “anti-Serbian”); introducing Global North knowledge and vocabulary in a country with strong anti-American, anti-EU feelings, anti-capitalist and anti-individualist traditions; reforming cultural policy and the cultural sector without replicating the self-governing socialist system, or the Global North’s, predicated on the commercialisation of culture and market as solutions (as propounded by UK, USA, German and French “capacity building” training provision to “upskill” cultural managers and help redesign the local cultural system).

Puerto Rico, an Island with 3.3 million inhabitants located in the Caribbean, was invaded by the US Army in July 1898 as part of the Spanish-American War. Since that moment, a process of assimilation and militarisation began, which was reflected in the public education system and other government programmes. It was not until 1952 that the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico was created, a form of political association that altered the colonial regime for purposes of international law. However, since that time, a large part of the educational, economic and legal models has been directly influenced by North American politics.

This political relationship influenced cultural policy. The creation of cultural institutions began in 1955. Although there has never been a ministry of culture, the functions and cultural policy actions of the first decades followed a very similar scope, a growing trend in the rest of Latin America. Starting in the 1980s, partly influenced by local governments that promoted statehood for Puerto Rico, the role of cultural institutions became limited, from being the custodian of cultural policy, to reproduce the approach of government as a facilitator, similar to the role of the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) (Hernández-Acosta, Citation2015).

While this was happening, many Latin American countries were transitioning to democracy (Martinell, Citation2009). Culture, thought from a much broader perspective, assumed a key role in promoting diversity and equity in multicultural settings. Cultural organisations assumed a role of custodians of cultural policy beyond managing arts programming, a new practice later termed “cultural agency” i.e. the exercise of “social interventions through creative practices” (Sommer, Citation2006).

The cultural policy and management curriculum

In the field of cultural policy and management we need to ask: whose culture, whose voices, whose writing and what bodies of knowledge are we imposing in our classrooms? In addition, what is the positionality of the student cohort in our courses which makes it more urgent to confront the “feelings that [the cultural and historical] gaze and knowledge production evoke in the students/learners” (Godsell, Citation2021, p. 5). Designing a curriculum requires critical choices and priorities about what and how to teach, why it has been chosen, how it will be assessed, with what pacing and sequence. It is also about the purpose of the curriculum, and understanding who the student cohort is.

There is a strong relationship between how we conceive of curriculum making and the decolonisation project since the curriculum “shape[s] how we see, think and talk about, study and act on the education made available to our students” (Cornbleth, Citation1988, p. 85); it “conveys views of reality, truth and knowledge in its practice” (Smith & Lovat, Citation1995, p. 13).

Those of us based in the Global South recognise that context-specific comes easily, if implicitly to us, with unplanned and unforeseen events in the curriculum that either enhance or detract from deep learning and engagement – a curriculum packed with (theoretical) “knowledge” detracts from the time needed to process this knowledge, assess its relevance and interrogate its usefulness. Though we are increasingly recognising the importance of explicitly identifying or communicating the epistemic virtues and transformations we want to instill in our students.

Bernstein’s pedagogic device (Citation1990) allows us to understand what knowledge is at the heart of the curriculum and frames the curriculum decolonisation process. He models the relationship between the fields of (knowledge) production, recontextualisation (of knowledge into curriculum) and reproduction (transmitting knowledge through pedagogy). It underscores the idea that theoretical knowledge is “socially powerful knowledge” so that all curricula, including vocational, must include theoretical knowledge (Shay, Citation2013, p. 564). The question of whose knowledge is foregrounded – a key argument in decolonisation – can be understood better if we recognise that the pedagogic device’s production, recontextualisation and reproduction fields are a social space of conflict and competition operated by the relevant agencies (curriculum authorities, tertiary and higher education institutions and government departments). It goes to the heart of how educators frame their relationship to the complex, changing cultural and creative sector while at the same time encouraging students to interrogate and critically analyse its internal contradictions.

Decolonising the curriculum

It is useful to unpack the many ways in which we speak about decolonisation. As educators we need to recognise how deeply the colonial project affected (and still affects) countries and their citizens. Overcoming the legacy of colonialism, involves decolonising the intellectual landscape of the country in question, and, ultimately, the mind of the formerly colonised. Fanon argues for the need “to liberate the black man from the arsenal of complexes that germinated in the colonial situation” (Citation2008, p. 14).

The corollary of this recognition is an acceptance and understanding of white privilege; the deep racial construction of the identity of white people everywhere and particularly those of the colonisers. As Vice writes,

It is by now standard […] to think of whiteness as consisting in the occupation of ‘a social location of structural privilege in the right kind of racialised society', as well as the occupation of the epistemic position of seeing the world ‘whitely' (Citation2010, p. 324).

In designing our curriculums and developing our pedagogic practice we need to be mindful of three concepts: epistemic silences, negation and grand erasure. Epistemic silences refer to the ways in which indigenous/local culture is displaced. Mignolo talks about the “unveiling of epistemic silences of Western epistemology” (Citation2009, p. 162) while South African decoloniality scholar Ndlovu-Gatsheni, defines epistemicide as “displacing African culture, pushing it to the margins of society, and unleashing epistemological violence against indigenous epistemology” (Citation2013, p. 181). Coined by South African sociologist Bongani Nyoka, negation in turn comprises African knowledge epistemicide, the exclusion of African theorists and theories, imposition of Western ideals and structures, and application of Western theories (Nyoka, Citation2013). Grand erasure highlights theoretical reflections which emanate principally from the intentions of metropolitan society to dominate our concerns which then erase the “experience of the majority of humankind […] from the foundations of social thought” (Connell, Citation2007, p. 47).

This means that decolonising the curriculum is not a once off action but a deeply activist concept which requires “epistemic disobedience” i.e. “de-linking (epistemically and politically) from the web of imperial knowledge” (Mignolo, Citation2009, p. 178); and the “dismantling of relations of power and conceptions of knowledge that foment the reproduction of racial, gender and geo-political hierarchies” (Ndlovu-Gatsheni, Citation2013, p. 14). Despite research, articles and books aiming to speak from the voice of the Global South, the marginalised and the subaltern, and to challenge Western thinking while developing concepts premised on local conditions, the achievement of decoloniality is a long-term process to be undertaken by students and faculty, challenging the ways in which curricula and delivery reproduce relations of power, inequality and deep racism.

Thus, decolonisation does not mean throwing out the canons of the field, or the authors from the Global North, but it does require us to question, interrogate, offer and apply alternative thinking. It is important that curricula give students access to this socially important knowledge as this “will determine whether they are part of society’s important conversations” (Shay, Citation2013, p. 580). As Mbembe writes:

… the Western archive is singularly complex. It contains within itself the resources of its own refutation. It is neither monolithic, nor the exclusive property of the West. Africa and its diaspora decisively contributed to its making and should legitimately make foundational claims on it. Decolonizing knowledge is therefore not simply about de-Westernization. (Citation2015, p. 24) (italics added).

Besides different bodies of knowledges, there are the different bodies in our classrooms with expectations or assumptions about their ways of coming to know. Decolonising the curriculum requires us to think differently about the pedagogic practices we employ in delivering the curriculum – from assessment strategies to pedagogies such as experiential learning and the transformations we expect in our student cohort. The bodies that inhabit our classrooms come with deep professional knowledge and cultural insights – we cannot ignore nor disrespect the worlds that students bring into classes and must recognise that students experience university as alienating, even as perpetrating a violence on their being (Mann, Citation2001). The decolonisation project has its core objective to fundamentally alter this experience.

An activist challenge to the global academic ecosystem is needed. It requires lecturers to be alert to what knowledges are being privileged as well as the distinction between knowledge of the powerful and powerful knowledge (Young, Citation2008) and to “the spaces, interactions, experiences, opportunities and settings in which formal learning takes place” (Knight, Citation2001, p. 374) so that our courses draw deeply on the lived experiences and professional lives of our participants to help shape the discussion, make sense of and interrogate theory in the contexts examined.

This means that academics and students must make their voices and perspectives present, changing the intellectual landscape in order to overcome the white male Western bias under which it still operates. This underscores that knowledge is at the heart of the curricula and the idea that it can influence being (Barnett, Citation2009, p. 435) - our students attest to the fact that our programmes have a transformative effect. The focus on enhancing and fostering the imagination thus needs to be combined with “pedagogies of presence”. Behind skills, competencies, knowledge, mental dispositions and value, “lies a substantive issue about the character and purpose of the curriculum” (Bridges, Citation1993, p. 44) and the social relations and institutional formats within which they occur – which takes us to an alternative conception of university.

Embracing a pluriversity approach

Faced with instrumentalisation, skills-based pragmatism and industry productivity many cultural policy and management programmes are frustrated by the corporatisation of the university, by the way in which the marketisation and managerialism of higher education are becoming benchmarks of institutional innovation (Dragićević Šešić & Jestrovic, Citation2017; Muller & Subotzky, Citation2001).

Mbembe (Citation2015) emphasises the importance of imagining what an alternative to the current university model would look like. Rather than replacing one system with another, or asserting a new absolute truth, it requires adopting a very broad kind of relativism - the belief that knowledge, truth and morality are all relative to the culture in which they operate so that we would still learn about Western practices, but they would become one possible idea, not absolute truth.

Grosfoguel describes a similar structure, what he calls a “pluri-versity”: a system that allows for epistemic diversity, instead of “uni-versity” where only one system of knowledge is considered as the absolute truth (Citation2012, pp. 84–85). He believes that a diverse range of knowledge and perspectives will contribute not only to the decolonisation of academia, but also to broad scale socio-political and economic liberation (Citation2012, p. 88).

The cases below illustrate decolonisation processes from three different contexts and social realities including the imperative that we privilege local theories and grounded views of reality, truth and knowledge; that space is provided for students to interrogate and question lecturers’ choices; and, that there is agency for students to embody the epistemic virtues and transformations they deem important.

Cultural policy and management case studies

School of Arts, University of the Witwatersrand, South Africa

South Africa’s apartheid legacy has left an indelible mark on the institutions, demographics and curricula of Higher Education. SA’s democratic dispensation did not ignore these glaring challenges (Mzangwa, Citation2019); the 1996 NCHE policy framework, for instance, drew an important distinction between closed knowledge systems driven by canonical norms of traditional disciplines, and open knowledge systems in a fluid and dynamic interaction with external social interests (NCHE, Citation1996). During the 1990s and 2000s, the focus was on transformation, to redress some of Apartheid’s political and economic violences; of structural inequality, racialised poverty, and in which HEIs are characterised as rich and white, or poor and black. The post #Feesmustfall era showed the spotlight on a third area of violence, the sphere of knowledge production itself, to question not only what and how we are teaching, but also the nature of the university. The epistemic violence wrought by a Western and colonial curricula and pedagogy gives priority to our agenda to decolonise higher education to reframe the curricula and pedagogy to achieve epistemic justice (Pillay, Citation2015).

It was only in the early 2000s, in response to increasing attention paid to the cultural sector – the 1996 White Paper on Arts, Culture and Heritage, the 1998 Cultural Industry Growth Strategy and establishment of Create SA, the skills development and training agency – that a cultural policy and management (CPM) programme was conceived. The professional management of institutions and events, encapsulated in this programme, was initiated by the late Paola Beck based at the University of the Witwatersrand’s Graduate School of Public and Development Management. It was later elaborated by two UK academics working in Johannesburg on cultural and infrastructure projects in 2001 who suggested that a postgraduate humanities cultural management programme would “feed” the work of the city of Johannesburg. The city co-funded the establishment of the Centre for Cultural Policy and Management at Wits’ School of Arts. Early course iterations reveal a vocational programme that focused more on skills training than on professional, knowledge-centered (higher) education.

Initial attempts to reconfigure the curriculum were designed to ensure that it was contextually rich with concepts, theories and case studies drawn from and rooted in the African context and reality whilst still attending to the key programme drivers which remained similar to those in the Global North (such as digital technologies, city making, cultural value, cultural entrepreneurship). Transformation and Africanisation were key not only to the core curriculum but also in meeting students’ needs (mostly African mid-level cultural sector managers, government officials and practitioners from South Africa and neighbouring countries). Students possessed a wealth of experience and expertise in the sector and CPM ensured that they would be able to access higher education. However, epistemic access remained elusive.

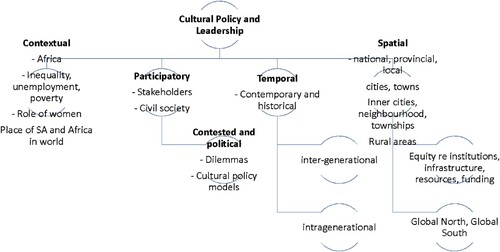

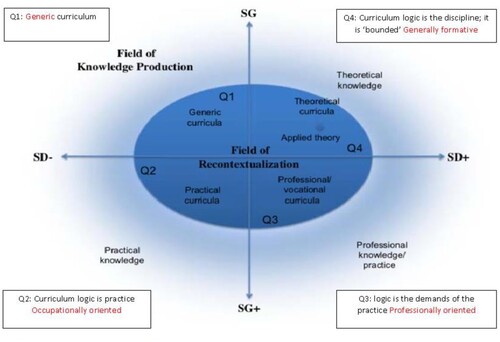

The decolonisation project began as an attempt to deepen contextualisation and recognise the differentiated knowledges at the heart of a CPM curriculum. Curriculum frameworks reveal “orders of meaning”, different logics and the bases of legitimation (Shay, Citation2013, p. 572). To address the challenges of epistemic access, the CPM programme was initially conceptualised as one where the curriculum logic was practice, and the courses were occupationally oriented (see Q2 in ) rather than for professional practice (Q3) rooted in theoretical knowledge (Q4).

Figure 1. Adaptation of Shay’s Differentiated knowledge framework (Citation2013) ©Taylor and Francis .

The knowledge was not recontextualised, and not differentiated in terms of vocational and professional knowledge. The first attempt to respond to the need for differentiated knowledge and curriculum was to increase semantic density (ideas, theory, practice) and semantic gravity (context, social and symbolic) by surfacing the theory behind the practice (see ), referencing local authors alongside the field’s canons, and exploring local cases to interrogate these theories. This was achieved by providing opportunities for experiential and practice-based learning. , designed for discussion with students, outlines the contextual, temporal and spatial dimensions of the field as well as the political contestations and the importance of stakeholder participation.

The process of making the insides of the field explicit enables epistemic access for students in a very real and authentic manner. CPM was able to collectively think through the curriculum logic and the demands of practice, and to make explicit how theory is “marshalled to make sense of the practice” (Shay, Citation2013, p. 575).

Since 2010 CPM has reflected on curricular appropriateness (Cornbleth, Citation1988, p. 87). An example of this was the development of a new semester long course on Culture, Creativity and the Economy (Joffe, Citation2018), in response to the prevailing economistic understanding of cultural and creative industries and its relationship to public sector support; the affordances and challenges of digital technologies; the emergence of cultural entrepreneurship; and, the persistent exclusions and elitism in Global South urban regeneration initiatives (Joffe, Citation2009).

Priority was given to Writing Intensive (WI) courses and to authentic assessments drawn from the South African and African contexts. WI courses embed varied writing, integrating writing and reading into weekly sequenced authentic assignments covering both typical cultural manager and academic practice: from concept maps and literature reviews to presentations, letters to ministers, opinion pieces and essays. The course redesign to foreground writing as a form of thinking has stimulated deeper reading and a greater degree of reflexivity amongst students. The WI courses offer formative, repeat opportunities for submission (as writing fellows are also former graduates) helping to develop the insider expert prose (MacDonald, Citation1994) required of a professional cultural manager.

Despite an environment that is fast paced and discontinuous, precarious, complex, and importantly, employment poor, the majority of our students successfully find or create work in the creative sector. As curriculum designers and lecturers, we attempt to find a balance between supporting students’ instrumental ambitions to their careers and, at the same time, developing their reflexivity to engage critically and meaningfully with the realities of the African cultural ecosystem, so painfully exposed during the Covid-19 pandemic: its precarity, normative advocacy, inequalities of representation, dominance of economic value and absence of any social safety net for the sector.

UNESCO Chair, University of the Arts in Belgrade, Serbia

At the beginning of the millennium, after democracy was restored in Serbia, the University of Arts in Belgrade started reconsidering its curricula, setting itself on the path of European integration, but also trying to revalidate forgotten knowledge produced in former Yugoslavia (connected with the Non-Aligned Movement) as an expression of postcolonial cosmopolitanism. During the 1990s, curricula were squeezed between demands for emancipation from Western knowledge which ignored humanities research of importance to Serbian society, and from Yugoslav knowledge and self-governing practices perceived as ideologically biased and of deliberately ignoring national identity issues (from non-Marxist authors to Serbia's medieval history), whilst looking to European Union accession and being recognised as culturally European. These politico-cultural complexities of the early 2000s prompted Serbian universities to start their search for epistemic justice by introducing new policies, content and teaching methods.

Although created in the early 1960s as an authentic expression of the Yugoslav socialist project, Westernised during 1980s, CPM education in the 1990s focused on national identity issues, disregarding former Yugoslav theories of cultural self-governance, as well the wider regional cultural space and the Non-Aligned Movement that nourished the previous cosmopolitan approach. This tantamounted to epistemicide as, since their inception in the late 1960s, Belgrade and Zagreb’s cultural policy schools had tried to find their way in the complex domain of CPM knowledge production (Dragićević Šešić, Citation2018).

Therefore, we had to develop subversity (Sousa Santos, Citation2017, p. 379) adding knowledge from the non-aligned Global South and from European and American semi-peripheries (e.g. Roma, Sami or Navaho nations), and to integrate them into our curricula. The struggle against epistemicide, inserting counternarratives and subaltern perspectives, demanded the re-writing of most of what was taught, leading to the creation of the “Interculturalism, Art Management and Mediation in the Balkans” programme, granted “UNESCO Chair” only two years later. It focused on cultural policies and management in Southeast Europe, knowledge that is relevant to over 10 countries but is usually omitted from Western literature, aiming to build students and teachers’ self-confidence in their personal professional capabilities, knowledge, encouraging them to research and theorise localised cultural development experiences, using previous, mostly forgotten knowledge (i.e. of the Praxis school).

The locally sourced curriculum including relevant global academic knowledge, was developed by scholars from Southeastern Europe and colleagues from the West; and although module names sounded universal e.g. cultural management, intercultural art projects, each module involved three academics: from Serbia, the Balkan region, and “international”, catering for students from the region, from the Global South (roughly two-thirds and one-third of the cohort), and a handful from the Global North who deliberately choose this programme to change their epistemological perspective.

To support regional knowledge and practice embeddedness, research-based learning was deployed as a core learning method. Students engage in empirical but comprehensive research projects as the basis of all assessment. Qualitative and ethnographic research methods allow them to produce narrative accounts of what is often regional practitioners’ implicit and intuitive (insider) knowledge. In other instances, problem-based or experiential learning teaching methods are used. The individual Masters thesis explores specific local issues, for example, explicit and implicit cultural policies in the region, the relevance of global concepts, how cultural practitioners and policy-makers respond to conflicting political demands such as national identity building, European integration, cosmopolitanism.

The programme – cosmopolitan and at the same time “Southern” – inspired the creation of several other decolonising pedagogic efforts: the first pan-Arabic Master in Cultural Management in Casablanca (supported by Al Mawred al Thaqafi [Culture Resource]) and the Strategic Management in the Art of Theatre programme in India, showing that knowledge beyond Northern epistemologies is possible.

A key challenge in the programme was that each student expected knowledge and respect of their country’s cultural practices and policies. These are often excluded from the Global North's body of knowledge and demanded the specific effort of teaching staff to expand their research horizons to offer relevant knowledge. As members of UNESCO and other international cultural expert groups, however, several academics had worked in different countries of the Global South, bringing different “peripheral” experiences, insisting on fair cultural relations and research practices that reflect culturally different entrepreneurial and cultural management methods i.e. from their Indian, Egyptian, Cambodian, Malian perspectives. The challenge was to integrate such findings with mainstream “CPM” thinking while avoiding “self-orientalising” by writing about these peripheries as the Other.

Our epistemic disobedience “took us to a different place, to a different “beginning” […] to spatial sites of struggles and building rather than to a new temporality within the same space” (Mignolo, Citation2011, p. 45). Agreeing with Mignolo about the pluriversality of decolonial thinking (Citation2011, p. 63), we try to articulate CPM thinking from the perspectives of different world peripheries, also participating in international projects that advocate the contribution of multiple voices in cultural development such as SHAKIN` Sharing Subaltern Knowledge Through International Cultural Collaboration (https://www.arts.bg.ac.rs/en/international/cooperation-in-eu-programmes/erasmus/strategic-partnerships/) or Stronger Peripheries: A Southern Coalition (https://strongerperipheries.eu/).

University of Sagrado Corazón, Puerto Rico

The case of Puerto Rico represents a scenario that helps understand the importance of decolonising theories and practices in arts management and cultural entrepreneurship. The country has essentially a Latin American culture, but subject to the political, legal and trade framework of the United States. In the case of the arts management discipline, the presence of models coming mainly from the North contrasts with the socioeconomic and cultural reality of the Island.

This context of Latin American culture exemplifies the importance of decolonisation in arts management education at three levels: the way of understanding “culture” and its management, the negative spillovers of philanthropy in the arts, and more recently, the influence of cultural entrepreneurship as part of the creative economy discourse.

Ethnic diversity in many of the Latin American countries led to the adoption of an anthropological conception of culture, including some that preferred the concept of culture in a plural way for public policy purposes. In the United States, the main focus has been on the arts (Mulcahy, Citation2006), creating a more limited scope in organisations that are categorised as part of this sector, whilst entities focusing on community development, or with intersections with other (political, social, environmental) dimensions, are often outside the reach of public cultural institutions; so most educational resources are limited to managerial knowledge and skills such as artistic programming, fundraising, marketing or finance.

The second level of influence from the North that greatly affects arts management in Puerto Rico is the role of philanthropy, mostly through foundations. The US model of support for the arts follows a trend of limited direct intervention, accompanied by tax exemptions that incentivises individual and corporate donors. Therefore, the foundations that support the arts use the services and programming of the sector to advance educational, access, participation and innovation initiatives. This support is limited to the programming, considering that operational expenses are generally covered by private donations. However, in the Latin American context, private patronage is in an incipient stage, so the sector cannot sustain economically only through the support for programming by foundations. Contrary to their expectations, this limitation ends up placing cultural organisations in a more precarious scenario as they end up self-subsidising administrative work.

Finally, the last decade brought a new creative economy discourse where the entrepreneurial nature of the arts and culture supported the promise of being an economic development engine (Buitrago & Duque, Citation2013). This prompted a valid question: if creative industries are an engine of economic development, why then do they need state support? Similarly, the new discourse imposed trends from the start-up/scale-up culture, without recognising the particularity of the arts in generating impacts beyond economic value. Entrepreneurship practices and strategies, relevant to the technology sector, are increasingly present in programmes and educational materials for the creative sector, even though most initiatives are based on the figure of the artist/entrepreneur, with limited or non-scalability potential.

Faced with this scenario, the universities in Puerto Rico began to question the existing models and practices from the United States to create a theoretical framework relevant to the Puerto Rican reality. With the creation of the Master’s in Cultural Management and Agency at the University of Puerto Rico over a decade ago, the importance of differentiating the concept of agency from management was addressed (Martinell, Citation2009). The programme provides a background in cultural studies and cultural policies that allows students to navigate the interdisciplinarity that cultural work requires. Likewise, it has the added value of curricular flexibility to meet students’ interest and needs, allowing approaches in specific arts sectors, community development, cultural rights and digital humanities among others.

More recently, the Universidad del Sagrado-Corazón had the opportunity to design undergraduate and graduate courses in cultural entrepreneurship, following the trends of self-employment in the creative sector and in alignment with the promotion of entrepreneurial mindset and activity. The assessment process from these courses, including an understanding of student expectations, their background, and of existing professional opportunities in the Puerto Rican cultural ecosystem, required adjusting the course from being an adaptation of a traditional entrepreneurship course to a new place/industry-based approach which has then been adapted to professional training, trainer-training and incubation initiatives. The main learnings of the process are detailed below:

A critical view of the entrepreneurship discourse: from an unquestionable acceptance of entrepreneurship as a solution, to understanding its negative spillovers, including aspects such as the precariousness of cultural work, self-subsidy, and digital business models where platforms monetise by exploiting creative content (Rowan, Citation2010). Also, the limits of entrepreneurship in arts and culture are established, including how discourse enables Government to reduce its responsibilities in the face of so-called self-management.

The entrepreneur as a cultural policy agent (Canclini, Citation1987): this premise, relating to all cultural stakeholders and not just government, suggests that entrepreneurs are also agents of cultural policy; so, they are not exempt of the responsibility of advancing objectives such as diversity, equity, access and participation, or cultural innovation. Regarding this, elements such as the United Nations SDGs are integrated to facilitate the analysis of the positive impacts that entrepreneurship may have on the ecosystem.

Business models determine scalability: in order to contextualise the application of business acceleration that is increasingly present in entrepreneurship education, emphasis is placed on the four business models of arts and culture, based on the product they generate: tangibles, digital content, services and/or experiences. This categorisation allows greater clarity in the growth potential of ventures and keeps the expectations aligned with the resources of the enterprise, including the limited access to capital in Puerto Rico.

The cultural mission as a starting point: it is recognised that entrepreneurship requires tradeoffs with the market that affect projects’ artistic and cultural values. Clarity in the cultural mission accepts this reality, placing the decision on the entrepreneur as to how far to accept tradeoffs (e.g. choosing between expanding markets and cultural innovation).

Cultural KPI’s: entrepreneurship education brings performance indicators mostly derived from the Tech industry, imposing them in contexts with little applicability. Thus, it is important that the entrepreneur defines their own indicators of success, adjusted to the sector or community/soft impacts.

These two experiences in Puerto Rico demonstrate the importance of addressing curriculum decolonisation based on two perspectives: the top-down exercise of designing programmes that address the country’s social, political and cultural context; and bottom-up efforts where the theoretical framework of an entrepreneurship course can evolve into a much broader curriculum design. The case of entrepreneurship as an example of discourses with colonial elements is also observed in other dimensions of education e.g. in the non-profit sector, that decontextualises and depoliticises a sector that has assumed responsibility for social action, including art and culture initiatives. While it is important to analyse ways to decolonise the curriculum at university level, it is also important to emphasise other educational fields of action that include incubators, accelerators and vocational programmes.

Discussion of cases

The decolonial project is clearly important for the CPM area of studies. Not only is the subject itself an applied field, but the field of application is culture. CPM studies deal with cultural production, the operation of cultural organisations that produce and disseminate it, the audiences that consume it, and the (cultural) ecosystems in which they operate that are in turn ingrained in local social environments, habitus, aesthetic codes, ways of knowing, doing and (cultural) economies. After completing their degree students transition from university to employment in their local creative milieux and thus expect their academic journey to include an element of authentic learning that helps them synthesise theoretical and applied understandings. In this applied, vocational sense, at its core, CPM is a cultural relativist subject.

As an academic subject CPM is deeply entwined in its Western origins – cultural and aesthetic capital, values, governance and management paradigms – and conception of the human – a homo-economicus/liberal humanist entity (Sonn & Stevens, Citation2021, p. 7). As an interdisciplinary field, CPM subjects operate across the boundaries and between the interstices of a range of traditional disciplines. CPM studies will typically engage with a mix of business and management, sociology, cultural studies, public policy, economics, human geography, urban studies, their sub-disciplines, and combinations thereof. This is mirrored in syllabus topics widespread across the globe like cultural management, creative cities, social enterprise, cultural policy, digital cultures, social impact or cultural consumption – and here lies a central problem: whose culture, whose creativity, whose society?

Although CPM has experienced significant growth at a global level in recent decades, the standard curriculum design and mainstream literature – including the expanding subject specific textbooks – originate in the West, reflect and address what are predominantly Western and, within this, largely Anglo-Saxon realities and models.

The internationalisation of higher education and global approach that the CPM field has fully embraced (which explains the enduring model syllabus) reflects the dynamics of geopolitical and economic power. One only needs to look at student mobility or how the CPM subjects are niche areas of research sustained by and large by the Western neoliberal knowledge “industry” (knowledge creation, dissemination, validation through impact factors and rankings) to realise their potential implications for the universalisation of Western cultural models.

There is therefore an epistemic tension in the CPM field between its primary object and need for situated learning (as a necessary condition for locally relevant pedagogy and educational outcomes), and the mainstream curriculum and (academic) knowledge structures that scaffold it. The three cases articulate this tension differently. There are clearly normative elements of a CPM curriculum that has been institutionalised and universalised through the (internationalised) university system (e.g. rankings, subjects), catering to the demand for global transferrable skills relevant to a global and connected cultural sector and workforce. Still, the implicit discourses and explicit priorities in the curriculum transformation agendas reflect disciplinary reflexivity and methodological situatedness – as expressions of certain spatially, geographically situated knowledge, affective and cultural systems, derived from particular sociohistorical-material conditions (Shahjahan et al., Citation2022, p. 76). Different ontologies are apparent in the repositioning of entrepreneurship to fit Puerto Rico’s agency framed cultural policy; in the Africanisation of the curriculum in South Africa; in the conceptualisation of Serbian cultural management in terms of interculturalism, mediation, (Balkan) regionalism and non-aligned cosmopolitanism.

In addressing this tension, a key issue for educators in all three case studies was the “positionality” (Icaza & Vázquez, Citation2018) of knowledge, geopolitical and cultural, and how to engage students with it, promoting their appreciation of the historical and political contingency of knowledge and, in this case, also its cultural embeddedness. For example, Sagrado-Corazón was faced with curriculum templates and educational practices widespread in US universities but not fully applicable to the Puerto Rican cultural ecosystem, and positionality in this sense involved the reframing of institutionalised discourse and (re)contextualising concepts of culture, cultural policy, entrepreneurship, within their local socio-cultural setting.

Engaging with positionality further involved encouraging student critical understanding and epistemic access to the “hidden curriculum” i.e. the (Western) assumptions about society and culture and (re)presentations of objects, discourse, body and affect that are embedded (and embodied) in mainstream literature and course models. In South Africa positionality entailed recontextualising course content and embedding student reflexivity in authentic learning and pedagogical practice. In Puerto Rico, to operationalise and (re-)contextualise the (US business) concept of entrepreneurship to fit with local values and notions of culture and policy, the course team reframed the concept in terms of (soft) cultural agency and realigned its business-related elements with the local cultural-business ecosystem.

In addition to the geopolitical and cultural positionality of knowledge (course content), a further tension in the CPM field concerns a global academic reality in which conceptual works and frameworks are (still) based on the grand narratives, ontologies and epistemologies generated by the disciplines and social realities of the West. This was a concern in the three cases and was especially visible in the Serbian case’s quest for emancipation from past European, Western knowledge hegemonies. As Morreira et al. (Citation2020) point out, in the absence of plurality and a common ground of being, in specific contexts, the application of dominant accounts of theory to practice and real-world phenomena entails the making of an interpretive judgement to cross conceptual-discursive gaps (Citation2020, p. 7). Thus, it is not about discarding the West’s narratives but about recognising their incompleteness (Nyamjoh cited in Gukurume & Maringira, Citation2020, p. 71).

Building epistemic justice into the discipline involves triangulating existing theory, local knowledge and epistemologies and allowing the mobility and exchange of ideas horizontally, cross-vertically and through myriad intersections (Gukurume & Maringira, Citation2020, pp. 71–72). In this respect, Serbia’s ambition gradually to evolve a Serbian (and Balkan) knowledge and social theory base and ultimately codify local CPM/subject theory points towards the future. Ultimately, it is the accounting for why a new (as it were) version of events is “understood as ‘new' that opens up space for further insights about historical and social processes” (Bhambra, Citation2014, p. 150); and for pluriversalising the existing academic canon/s.

The cases revealed the pedagogic strategies deployed to ease students’ connection with the positionality of course content and how educators drew on local space and materiality as decolonial teaching tools, pedagogies of “emplacement” (Morreira et al., Citation2020). Such pedagogies not only seek to integrate student personal experience with place into learning but recognise local knowledge, epistemology and culture as the foundation upon which situated learning should build. In our three cases, educators focused learning and teaching on local cultural practices and issues, invited local practitioners/speakers to examine those issues from a local (knower) perspective and developed various methods of student immersion in local cultural practice. As Mignolo and Walsh (cited in Sonn & Stevens, Citation2021) state, “decoloniality is understanding how coloniality affects how individuals think and feel about themselves, how they make sense of reality, how they relate to others and perceive constraints or possibilities” (Citation2021, p. 7). Emplacement is eminently a pedagogy of positionality – where students themselves are viewed as knowers and pluriversal knowledge-makers situated in a cultural context (Morreira et al., Citation2020).

Conversely, educators addressed the theoretical side of positionality and the CPM tension by deploying pedagogical approaches based on active, independent learning. These are particularly suited to a field like CPM, that is characterised by a mix of practice, theory and interdisciplinarity (arising from the engagement with situated practice “out there”). Interdisciplinarity entails the triangulation of breadth, depth and synthesis and the reinterpretation of disciplinary goals and concepts in view of a specific real-life problem. Interdisciplinary pedagogy’s primary concern is with learner agency, as Haynes (cited in Chettiparamb, Citation2007) writes, “with fostering in students a sense of self-authorship and a situated, partial and perspectival notion of knowledge that they can use to respond to complex situations” (p. 32). We note here how the student agency, application and synthesis concerns of interdisciplinary pedagogy were shared by all three cases where individual research was deployed as a means to fulfil decoloniality’s aspiration to emphasise the knower rather than the known – and in so doing, countering epistemic injustice (Fricker, Citation2007) – and to allow the latitude for bridging the interpretive gaps between given theory and local practice.

Conclusion

This paper discussed how the decolonial turn was realised in three cases and how the pursuit of a pluriversal knowledge ecology found expression in the curriculum, content and the pedagogical practices that were deployed to enable the delivery of locally relevant educational outcomes. It underlined how educators resolved the ontological and epistemic discontinuities between the standard disciplinary canon and local realities to embed and contextualise the discipline and help students make sense of what happens in the(ir) real world. We reviewed the disciplinary context of the CPM area of studies, unpacking the tensions entrenched in the field, identifying and discussing the key issues that confronted the above cases in their decolonial journey.

We do need to ensure our programmes are transformative to develop critically engaged citizens able to speak truth to power, and it is imperative that these Global South voices are documented in the form of research reports, journal articles and opinion pieces. While the CPM programme increasingly conforms to an epistemically diverse curriculum (Luckett, Citation2001), questions of how we teach, how students learn and what and how we assess are constantly being addressed to ensure students develop required epistemic virtues, dispositions and qualities (Barnett, Citation2009) to deal with the complexities of cultural governance on the African continent, in Latin American context and at the European semi-periphery of Serbia.

Acknowledgements

The Serbian case study was developed as part of EPICA - Empowering Participation in Culture and Architecture: (ID 7744648), supported by the Science Fund of the Republic of Serbia.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Barnett, R. (2009). Knowing and becoming in the higher education curriculum. Studies in Higher Education, 34(4), 429–440. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070902771978

- Bernstein, B. (1990). The Structuring or Pedagogic Discourse. Routledge.

- Bhambra, G. K. (2014). Connected Sociologies. Bloomsbury.

- Bridges, D. (1993). Transferable skills: A philosophical perspective. Studies in Higher Education, 18(1), 43–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079312331382448

- Buitrago, F., & Duque, I. (2013). The Orange Economy. International Development Bank.

- Canclini, N. G. (1987). Políticas culturales en América Latina. grijalbo.

- Chettiparamb, A. (2007). Interdisciplinarity: A Literature Review. The Interdisciplinary Teaching and Learning Group, University of Southampton.

- Connell, R. (2007). Southern Theory: The Global Dynamics of Knowledge in Social Science. Polity Press.

- Cornbleth, C. (1988). Curriculum in and out of context. Journal of Curriculum and Supervision, 3(2), 85–96.

- Dragićević Šešić, M. (2018). Culture and democracy: Cultural policies in action: Is cultural policy theory possible at the semi-periphery? Kultura, 160(160), 13–35. https://www.casopiskultura.rs/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/prevodi/6.%20Milena%20Dragicevic%20Sesic,%20CULTURE%20AND%20DEMOCRACY,%20Culture%20No.%20160,%202018.pdf https://doi.org/10.5937/kultura1860013D

- Dragićević Šešić, M., & Jestrovic, S. (2017). The university as a public and autonomous sphere: Between enlightenment ideas and market demands. In S. Bala, M. Gluhovic, H. Korsberg, & K. Röttger (Eds.), International Performance Research Pedagogies (pp. 69–82). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Fanon, F. (2008). Black Skin, White Masks. Pluto Press.

- Fricker, M. (2007). Epistemic Injustice: Power and the Ethics of Knowing. Oxford University Press.

- Godsell, S. (2021). Decolonisation of history assessment: An exploration. South African Journal of Higher Education, 35(6), 101–120. https://dx.doi.org/10.20853/35-6-4339

- Grosfoguel, R. (2012). The dilemmas of ethnic studies in the United States: Between liberal multiculturalism, identity politics, disciplinary colonization, and decolonial epistemologies. Human Architecture: Journal of the Sociology of Self-Knowledge, X(1), 81–90.

- Gukurume, S., & Maringira, G. (2020). Decolonising sociology: Perspectives from two Zimbabwean universities. Third World Thematics: A TWQ Journal, 5(1-2), 60–78. https://doi.org/10.1080/23802014.2020.1790993

- Hernández-Acosta, J. (2015). Designing cultural policy in a post-colonial colony: The case of Puerto Rico. International Journal of Cultural Policy, 23(30), 285–299. https://doi.org/10.1080/10286632.2015.1043288

- Icaza, R., & Vázquez, R. (2018). Diversity or decolonisation? Researching diversity at the University of Amsterdam. In G. K. Bhambra, D. Gebrial, & K. Nişancioğlu (Eds.), Decolonising the University (pp. 108–128). Pluto Press.

- Joffe, A. (2009). Creative cities or creative pockets: Reflections from South Africa. In A. C. Fonseca Reis, & P. Kageyama (Eds.), Creative City Perspectives (pp. 50–59). Garimpo de Soluções & Creative City Productions. https://docplayer.net/3961619-Ana-carla-fonseca-reis-peter-kageyama-org-creative-city-perspectives-1-st-edition.html

- Joffe, A. (2018). Pedagogy as activist practice: A reflection on the cultural policy and management degree in South Africa. Arts and Humanities in Higher Education, 18(2-3), 178–196. https://doi.org/10.1177/1474022218824558

- Kiossev, A. (1995). The self-colonization cultures. In D. Ginev, F. Sejersted, & K. Simeonova (Eds.), Cultural Aspects of the Modernisation Process (pp. 73–81). TMV Senternet.

- Knight, P. T. (2001). Complexity and curriculum: A process approach to curriculum-making. Teaching in Higher Education, 6(3), 369–381. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562510120061223

- Luckett, K. (2001). A proposal for an epistemically diverse curriculum for South African higher education in the 21st century. South African Journal of Higher Education, 15(2), 49–61. https://doi.org/10.4314/sajhe.v15i2.25354

- MacDonald, S. P. (1994). Professional Academic Writing in the Humanities and Social Science. SIU Press.

- Mann, S. J. (2001). Alternative perspectives on the student experience: Alienation and engagement. Studies in Higher Education, 26(1), 7–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070020030689

- Martinell, A. (2009). Las interacciones en la profesionalización en gestión cultural. Cuadernos del CLAEH, 2(32), 97–115.

- Mbembe, A. (2015). Decolonizing knowledge and the question of the archive. [Lecture], University of the Witwatersrand, 9 June. http://wiser.wits.ac.za/system/files/Achille%20Mbembe%20-%20Decolonizing%20Knowledge%20and%20the%20Question%20of%20the%20Archive.pdf

- Mignolo, W. D. (2009). Epistemic disobedience: Independent thought and de-colonial freedom. Theory, Culture & Society, 26(7-8), 159–181. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263276409349275

- Mignolo, W. D. (2011). Geopolitics of sensing and knowing: On (de)coloniality: Border thinking and epistemic disobedience. Postcolonial Studies, 14(3), 273–283. https://doi.org/10.1080/13688790.2011.613105

- Morreira, S., Luckett, K., Kumalo, S. H., & Ramgotra, M. (2020). Confronting the complexities of decolonising curricula and pedagogy in higher education. Third World Thematics: A TWQ Journal, 5(1-2), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/23802014.2020.1798278

- Mulcahy, K. (2006). Cultural policy: Definitions and theoretical approaches. The Journal of Arts Management, Law, and Society, 35(4), 319–330. https://doi.org/10.3200/JAML.35.4.319-330

- Muller, J., & Subotzky, G. (2001). What knowledge is needed in the new millenium? Organization, 8(2), 163–182. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350508401082004

- Mzangwa, S. (2019). The effects of higher education policy on transformation in post-apartheid South Africa. Cogent Education, 6(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2019.1592737

- NCHE. (1996). Green Paper on Higher Education Transformation. https://www.education.gov.za/Portals/0/Documents/Legislation/Green%20Papers/Green%20Paper%20on%20Higher%20Education%20Transformation.pdf?ver=2008-03-05-104602-000

- Ndlovu-Gatsheni, S. J. (2013). Empire, Global Coloniality and African Subjectivity. Berghahn Books, 177–195.

- Nyoka, B. (2013). Negation and affirmation: A critique of sociology in South Africa. African Sociological Review, 17(1), 2–19.

- Pillay, S. (2015). Decolonising the University. Africa is a Country. Retrieved April 25, 2022, from http://africasacountry.com/2015/06/decolonizing-the-university/

- Rowan, J. (2010). Emprendizajes en cultura. Discursos, instituciones y contradicciones de la empresarialidad cultural. Traficantes de Sueños.

- Shahjahan, R., Estera, A., Surla, K., & Edwards, K. (2022). “Decolonizing” curriculum and pedagogy: A comparative review across disciplines and global higher education contexts. Review of Educational Research, 92(1), 73–113. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543211042423

- Shay, S. (2013). Conceptualizing curriculum differentiation in higher education: A sociology of knowledge point of view. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 34(4), 563–582. https://doi.org/10.1080/01425692.2012.722285

- Smith, D. L., & Lovat, T. J. (1995). Curriculum Action and Reflection Revisited. Social Sciences Press, 6–23.

- Sommer, D. (2006). Cultural Agency in the Americas. Duke University Press.

- Sonn, C. C., & Stevens, G. (2021). Tracking the decolonial turn in contemporary community psychology: Expanding socially just knowledge archives, ways of being and modes of praxis. In G. Stevens, & C. C. Sonn (Eds.), Decoloniality and Epistemic Justice in Contemporary Community Psychology (pp. 1–20). Springer.

- Sousa Santos, B. (2017). Decolonising the University: The Challenge of Deep Cognitive Justice. Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

- Vice, S. (2010). How do I live in this strange place? Journal of Social Philosophy, 41(3), 323–342. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9833.2010.01496.x

- Young, M. (2008). From constructivism to realism in the sociology of the curriculum. Review of Research in Education, 32(1), 1–28. https://doi.org/10.3102/0091732X07308969