ABSTRACT

With government-imposed lockdowns due to the COVID-19 pandemic, one would expect the videogames industry to experience a windfall as locked-down individuals turn to games to fill the time. Despite successful profit margins for game studios, a multitude of issues have affected videogames freelancers, with this paper displaying how the pandemic has not been plain sailing for the industry. Informed by 31 interviews with freelancers and videogames practitioners, this paper adds to knowledge on the viability of worker co-operatives and how they offer hope to those workers looking for more emotional and financial security post-pandemic. The paper concludes by suggesting that although co-operatives provide alleviation for workers against a multitude of concerns, there needs to be more education, promotion and funding for co-ops to make them an accessible corporate structure.

Introduction

The corporate structure – with its traditional hierarchies of employers and employees, line and middle managers – has been embedded in economic landscapes for centuries. However, at the fringes have always been alternative and experimental ways of creating more equitable forms of economic institutions, with one of the most prominent of these being “co-ops”.

In the UK, there are two main forms of co-operatives, consumer-owned co-ops, such as The Co-operative Group supermarket, which is probably the most well-known co-op in the UK, and worker-owned co-operatives which are for the benefit of workers themselves (Ranis, Citation2016; Restakis, Citation2010). The ability for co-operatives to exist in a kaleidoscope of ways is shown in the UK economy, where many sectors have utilised them for an economic structure (Boyle & Oakley, Citation2018). However, in one of the largest, most successful and dynamic sectors of the UK – the creative industries – is a sector which has only just started to see the advent and benefits of co-operative working groups; the videogames industry.

The video games industry, like many others, has characteristic top-down working structures, with studios being owned by a few “Directors” and then employing a core team, which can then expand to vast numbers during projects through taking on freelance labour (Bulut, Citation2020; Woodcock, Citation2019). Whilst the industry is not unique in its hiring of freelancers, which also happens in other facets of the creative industries, the scale of which those that undertake precarious portfolio-based work is sizeable. The nature of this portfolio-based work means that this freelance labour has the potential to be exploitative with poor working conditions (Banks & Hesmondhalgh, Citation2009; Mould et al., Citation2014; Woodcock, Citation2019) and therefore the concept of co-operatives could be particularly effective for these groups.

This paper takes on the call in Boyle and Oakley’s (Citation2018) report on co-operatives in the creative industries, which asks for greater research and understanding of co-operatives and their utility within the creative industries. The primary research for this paper was conducted over a year, following the 2020 COVID-19 outbreak, and comprised of a combination of 30 socially distanced interviews with freelancers, employers and co-operative members as well as one focus group.

The paper first introduces the UK videogames industry, highlighting the nature of the industry and its economic significance in the UK’s creative industries. Additionally, this section will explore the experience of freelancing in the videogames industry and the impacts of the COVID-19. Secondly, the UK’s co-operative landscape will be explored, laying down context to a model which is often overlooked. Lastly, this paper will discuss the emancipatory potential of co-operatives in the videogames industry in building resilience and allowing freelancers to resist changing business models and working structures which can have negative implications on workers.

Videogames industry working mechanics

The videogames industry is considered to be a contemporary facet of the creative industries (Heinman, Citation2015) due to its relatively young age compared to other areas, such as theatre. The UK games industry has been growing since the 1980s, and over the past 40 years in 2019 was estimated to be worth £5.35bn according to the industry body Ukie (Citation2019). The industry is composed of three different segments; development, publishing and retail, all of which play a different role in the success of the industry (Woodcock, Citation2019). In the UK it is estimated that 86% of people aged 16–69 have played computer or mobile games in the last year, with 54% playing “most days” (Sanvanta, Citation2020; Ukie, Citation2019). The games industry parallels the entertainment industry in how it operates, as the games that studios produce must appeal to the audience, their fan base, in order to be successful. However, the key difference is that making games requires extensive, and unique, knowledge about computer software due to its robust stance of straddling the border between art and technology (Schreier, Citation2017). The videogames industry has seen the rise of large AAA, and smaller indie, studios. The term AAA is often debated in academic discourse (see Lipkin, Citation2013), but for the purposes of this article, it shall be defined as a videogame corporate giant which produces mainstream, high-quality, games that are developed by large teams with multi-million pound budgets. UK-based AAA companies, such as Rockstar North and Lionhead Studios are companies that have produced games that have developed into extremely successful, profitable and well-loved franchises. Examples of AAA games from these studios that have soared in popularity over years the include Grand Theft Auto and Fable II, which have expanded across multiple consoles and still have a dedicated fan-base that continue to come back to play time and time again.

The alternate side of game production, aside from AAA studios, are indie studios. These smaller studios don’t have profit turnovers that are as high as AAA studios and therefore they have less financial influence (LaLonde, Citation2020) in the industry. In the UK, on average, indie studios tend to have fewer resources than the larger corporations and often do portfolio-based work, taking on fewer projects due to having smaller teams. Although success can come from independent studios, running an independent studio is like “juggling dangerous objects” and if they don’t have “a new contract ready to go as soon as the last one is finished, [you’re] in trouble” (Schreier, Citation2017, p. 2). This brings a level of precarity for those trying to start their own studios, particularly for those in management positions, which can drive them to choose alternate forms of employment. In an interview, a freelance game designer from Dundee, Scotland, mirrored these concerns from his past attempt to start an indie games studio. The designer, now running a collective for freelancers, described how he started a studio with four friends after graduating from a Master’s degree, with £25,000 of funding. They then employed two other graduates, forming a small indie games development studio, which saw success initially, with “revenue [going] go up every year” and he states they were “on paper, doing really well” even if they, as the designer admits, were “making it up as [they] went along”. Although the indie studio experienced success in the initial period, after four years, the founding members “all fell out with each other because it had quite a detrimental impact on [their] mental health”. Starting out as friends, the relationships “actually soured” and for some in particular, the process of starting and running an indie studio “was seriously difficult, mental health wise”. The stories outlined by this once-indie game developer are echoed by the work of Whitson et al. (Citation2018, p. 15) where they describe indie development as “unpredictable, exhausting and unsustainable”. The mental strain sitting on a select few founding members to make the studio work, has significant impacts on mental health, making this unsustainable without appropriate avenues of support.

Both AAA and indie game studio make up the foundations for the UK games industry and are responsible for the vast majority of economic value. However, as Woodcock (Citation2019) states, only those companies with over 50 employees or a certain turnover have to report business data, of which only 6% can offer information for due to being small and medium enterprises (SME) or freelancers. Mould et al. (Citation2014) identify the significance of freelance labour throughout the creative industries and the crucial role they play in “performing the creative work in a firm-dominated sector, as well as stitching together the sector as a whole” (p. 2437). This is due to the nature of project-based work in the creative industries, with freelancers being drafted in to “add value to the creative process” (Mould et al., Citation2014, p. 2452) and to make up large proportions of creative labour. Although freelancers have a crucial role in the creative industries, their project-based work is exceedingly precarious, with the precarity manifesting in many ways. For example, Mould et al. (Citation2014) highlight that freelancers encounter increased risk, short-termism, low levels of unionised representation and constant termination. Many companies, particularly SMEs that scale up rapidly during the production process, reply on freelance labour to take on more contracts and work to tight deadlines. However, freelancers in the creative industries, especially the videogames industry, quickly discover that there is a contrast between the utopian job descriptions and the reality of inequality, insecurity and exploitation in their work (Banks & Hesmondhalgh, Citation2009). The structural precarity of the games industry job market effects workers looking for jobs at AAA and indie studios, as well as those who have sought to freelance and have moved with the industry shift towards individualism. Whitson et al. (Citation2018, p. 17) state that these “long-standing and complex inequalities and injustices in the game industry can be better discerned and redressed by shifting the frame of the conversation away from both individualizing aspects of creative work and gross ideologies of games as art or games as commerce” and if we want to make sustainability in the game industry a viable reality, “we need to make social organization – not individual actors, the games themselves, nor the larger political economic structures of the industry – our central unit of analysis”.

The co-operative landscape in the UK

When trying to define co-operatives, it is exceedingly difficult, with Emelianoff (Citation1942, p. 13) describing them as a kaleidoscope of diversity, with their variability being “literally infinite”. More recently though, Zeuli et al. (Citation2004) identify two definitions that are commonly used when describing co-operatives, from the International Co-operative Alliance (ICA) and the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). The ICA (Citation2021, n.p.) defines a co-operative as an “autonomous association of persons united voluntarily to meet their common economic, social, and cultural needs and aspirations through a jointly-owned and democratically-controlled enterprise” whereas the USDA defines a co-operative as “a user-owned, user-controlled business that distributes benefits on the basis of use” (United States Department of Agriculture, Citation1994, n.p.). These definitions, when used in tandem, recognise that co-operative membership is voluntary and has a deep-rooted belief in mutual help. Additionally, it outlines three principles of co-operatives: Ownership, control and a proportional distribution of benefits for users (Zeuli et al., Citation2004, p. 1).

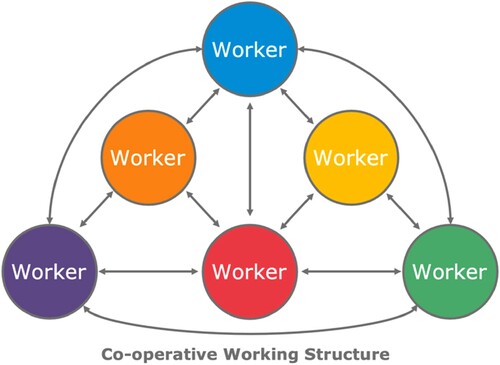

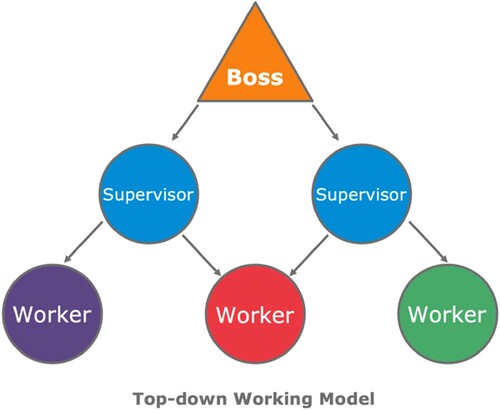

The structural difference between top-down working models and co-operative working groups can be seen in and . shows the normalised capitalistic employment structure that is widely utilised today, which is top-down in nature and has a boss at the top of the hierarchy telling workers what to do. A co-operative, outlined in , re-imagines the socio-normative working patterns by placing all individuals that work at the company at equal levels of authority; everybody has a stake in the business, and everybody is treated evenly.

Boyle and Oakley (Citation2018) discuss the benefits of co-operatives in their report, highlighting previous research from Perotin (Citation2016), the Employee Ownership Association (Citation2017) and the New Economics Foundation (Citation2018). Research has shown that worker co-operatives survive at least as long as other businesses as well as having more stable employment. Additionally, they are more productive than conventional businesses due to staff working “better and smarter”. Regarding financials, past research also shows that worker co-operatives retain a larger share of their profits and that pay differentials between executives and non-executives are much narrower than other firms. One of the key positives when considering the utility of co-operatives following the COVID-19 pandemic, highlighted by Boyle and Oakley (Citation2018, p. 7), was that in employee-owned co-operatives there is “greater resilience than non-employee-owned businesses during the economic downturn”. The flexibility of co-operatives, highlighted by Co-operatives UK (Citation2017) allows members to decide how they are run, and how they are governed. During a pandemic, this also allows for flexibility in working patterns, workloads and support given, something which conventional businesses haven’t been able to do.

Whitson et al. (Citation2018) identified that co-operative systems and non-alienated labour is often dismissed as romanticised delusion, and when this happens collective support structures become eroded, de-regulated, de-funded and downsized. However, in the UK, there are currently 7063 official co-operatives with 14 million members, generating 38.2 billion pounds in annual turnover (Co-operatives UK, Citation2020). Although not all these members are from worker co-operatives and may be members of shops such as The Co-operative or John Lewis, this is still a significant amount of people in the UK that are interacting with co-operative working practices.

Co-operatives London, who promote co-ops in the city, identify there being at least 600 co-ops which employ over 8000 people in the region (Co-operatives London, Citation2020). London’s established worker co-ops include Cycle Training UK, Cave Co-operative Sustainable Architects, OrganicLea growers, Calverts graphic designers and printers and Outlandish web developers. These co-operatives, according to co-operatives London are seen as social champions, and ground breakers in their trades and professions. They have demonstrated the ability for worker co-ops to be successful in many different sectors. Calverts, for example, operates in the creative industries and have been running since the 1960s. They are a successful graphic design business that help fellow co-ops with their policy papers and are advocates for the co-operative movement. These more established co-operative working groups have also inspired London’s new and young co-ops, subverting the societal norms of their industries in what they do and how they do it, such as Ceramics Studio Coop and Blake House Filmmakers.

Although London has a successful co-operative ecosystem, there are, at present, no specific computer game co-operatives that operate in the city. While the games industry workers union “Game Workers Unite” (GWU) has a section on their website for forming worker co-operatives and the process to do so, there are very few in the UK, let alone London. One notable co-operative that operates in the UK is a worker co-operative composed of freelancers working as game writers. On their website, they make it clear the reasons for forming a co-op, such as collective bargaining, insurance and financial security. Additionally, they identify being able to extend non-disclosure agreements (NDAs) across the entire co-operative rather than one freelancer. This allows a larger support network for any issues that could occur, clearly displaying the emancipatory potential of co-operative working groups for freelancers. There are a handful of other examples of worker co-operatives from around the globe, from France to Canada, displaying that the model is transferable to this facet of the creative industries. Therefore, we can see worker co-operatives as a viable option in the creative industries, and thus, the video games industry.

Methodology

The primary research for this paper spanned across a year and consisted of semi-structured interviews with those working in the UK videogames industry. A range of practitioners in the industry were interviewed ranging from employers, union representatives and freelancers themselves. When planning for the interviews, participants were researched via methods such as Twitter and LinkedIn to see their industry experience, and from this, 10 open-ended questions were written down to steer the conversation. The 10 questions were different for each participant, tailoring them to their job, gender and work experience to fully engage with individuals. For example, female participants were asked about their experiences as a woman in the games industry due to documented harassment and marginalisation (Jenson & De Castell, Citation2013) and freelancer employers were asked when freelancers are needed in the production process. These interviews lasted at least an hour in length each, with some lasting an hour and a half if the participant felt comfortable talking. An example of the 10 questions asked for one freelancer are:

Could you tell me how you got into the videogames industry?

What made you decide to freelance? What are the positives?

What are the drawbacks of freelancing?

What methods do you use to find contracts?

Do you think there is enough support for freelancers in the videogames industry? Why/why not?

Do you think there is enough education on how to freelance and the nature of the work?

Have you freelanced in other creative industries? How do they compare to videogames?

How did COVID-19 effect your work and personal life?

Are you a union member? What’s your opinion of the union?

Are you a member of any support groups, whether online or in person?

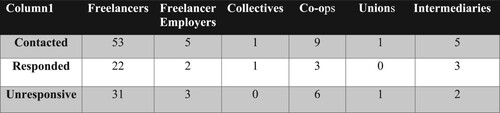

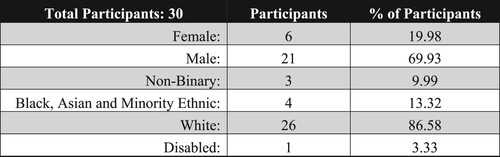

displays the groups interviewed, how many people were contacted and the response rate for the interviews, whereas shows the breakdown of gender, ethnicity and disability of interview participants.

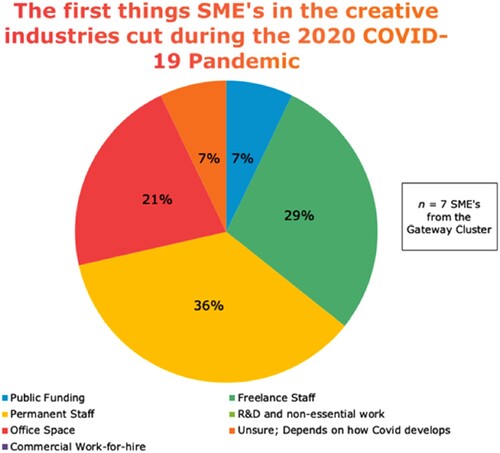

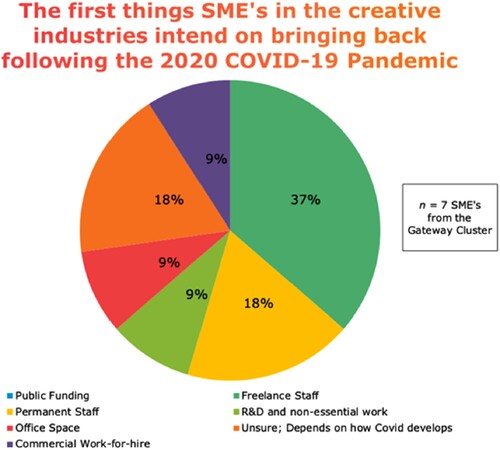

Research methods were social distancing friendly, due to the COVID-19 pandemic and utilised video call software such as Zoom. The use of these technologies allowed remote interviews, enabling participants to remain comfortable and safe. Due to the elusive nature of freelancers, and how thinly spread their time is due to their portfolio work and juggling multiple contracts, finding participants was difficult and became reliant on word-of-mouth recommendations. In addition to interviews, a focus group was conducted with seven small or medium sized enterprises (SMEs) from the Gateway Cluster (StoryFutures, Citation2021), who employ freelancers to discuss how they responded to the COVID-19 pandemic and how their responses affected freelancers. All participants in this study were anonymised for ethics purposes and to prevent potential repercussions from current or future employers.

Freelancing through COVID-19: struggles and precarity

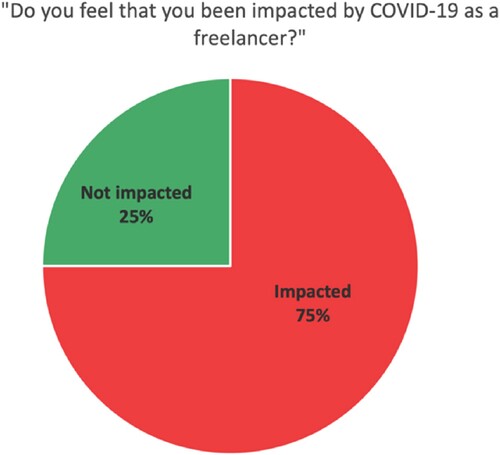

Freelancing is often fetishised as a way of having more control over your working pattern, and for many individuals it does just that, however, for some it doesn’t have the desired effect, especially when faced with a global pandemic. The research conducted for this article highlights the struggles freelancers have faced during the COVID-19, which highlights how precarious their work can be. Although some individuals felt they had not been impacted by the pandemic, such the co-operative members interviewed, most freelancer participants (75%) had been negatively impacted, as illustrated in .

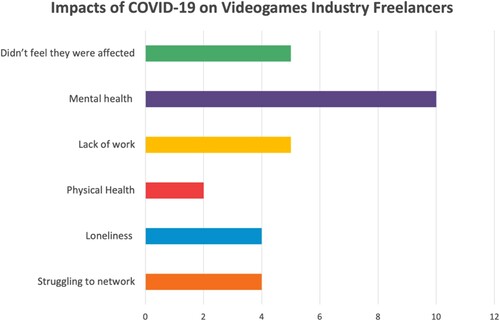

The participants that stated they had been impacted by the pandemic highlighted many different reasons, which have been categorised into the five areas shown in .

As seen in , the most frequently discussed impact was Mental health due to the series of government-imposed lockdowns. For example, one freelancer said COVID and being made to work from home “absolutely impacted my mental health” as “There is definitely the whole mental aspect that when you leave the office, you leave the work there”. Another freelancer said that home working made it “very easy for it [work and home] to all blur into one” which they described as being “not healthy” for “mental health and general well-being”. The impact on mental health has had a notable effect on motivation and consequently on productivity. This was recorded in an interview where the participant stated COVID had “just generally eroded my motivation, and discipline with time. I feel like I’m probably 30 or 40% less productive overall, than I was before, just through like 1000 small cuts, you know, just sort of like a gradual draining thing”. It is important to note that many of these mental health issues highlighted were because of some of the other impacts. For example, another freelancer stated

with regard to my mental health, I went through a season of depression and that led to me having a period where I was doubting whether or wanting to continue freelancing and working in the games industry as a whole. And I think a lot of that is to do with, you know, having a year where I practically had no work. And then obviously, you get in your own head, because you've had so much stripped away from me in terms of like, your freedom, and your routine.

This participant wasn’t alone with a combination of impacts, with another expressing both their “mental and physical health” had been impacted, resulting in them getting “a lot more stressed a lot more anxious”. One of the co-operatives interviewed highlighted that they didn’t “know anyone in industry who hasn’t had a rough moment” in the pandemic and as a result they had become “a big advocate of trying to normalise things like mental health and talking about physical health”.

A further impact underlined specifically by freelancers was loneliness, which one of the participants stated, “freelancers enjoy freedom … if that’s taken away, then I think a lot of people have felt distanced and alone”. Another freelancer experiencing similar issues described how NDAs also led to further isolation during the pandemic. They highlighted

It can get messy, you know, with things like NDAs, or with the games industry being so small, you don’t know who knows. A lot of people know each other. I’ve found it feels like everyone knows everybody. So, you never want to share [problems]. There are a lot of times where I just get very worried, especially with freelancers who can get really worked up, and it does feel like they don’t know who to speak to sometimes.

The transition of casual communications going online left some freelancers feeling stressed due to an added paper trail. If workers were reported to employers it could result in them not only losing contracts in a time where many freelancers were struggling to find work, but also the tarnishing of their reputation in the industry. For some, having in-person interactions at conferences and events was a chance to make friends and have valuable moment to discuss issues and concerns. A further freelancer stated

I’ve been so isolated from the industry, you know, I attended a lot of events before the pandemic happened. And even though, a lot of the time, that did to trigger anxiety. For me, it's something that I did end up missing and it's a missing part of my life

due to being able to make “meaningful relationships with people” not only for “career progression” but also as they admittedly “don’t have a lot of friends. So it’s nice to just have those people there”. Cutting off contact for individuals that struggle to make friends and to interact socially online has resulted in cumulative loneliness for these workers. Another participant stressed how with the lack of office work, freelancers can no longer “go to the watercooler, have a chat with someone, and get social fixes” making an already independent and solo working style even more isolated. The government-imposed lockdown meant that those that actively organised meetups within the industry to alleviate loneliness for workers struggled to do so. One participant who before the pandemic used to organise Women in Games events described that because of COVID, she “just didn’t have mental space for like doing any organisation” due to being “quite low with transitioning to remote work” and thus was “finding that quite tough” to find the willpower to spend extra time in front of the computer after a day of work. Furthermore, she noted “it’s not the same as well … I’ve been to some webinars and things and you don’t see anyone else in the audience, you don’t really get to interact, it feels much more passive” reducing the capacity of events to alleviate loneliness.

One of the final impacts raised was having a lack of work, which had implications for stress and anxiety for workers, with one freelancer saying “on a practical basis on a lot of it [work] disappeared” which resulted in them “Having to work longer hours just to try and find work” and another stating “everything shut down … I didn’t have any games work at all”. For many freelancers, they argued COVID-19 had shown how precarious their contract-style work can be. This stemmed from many companies cancelling contracts with freelancers when the pandemic hit to survive.

and display answers given during a focus group regarding COVID-19’s impacts. shows what the first things SME’s in the creative industries cut during the pandemic were with both permanent and freelance staff being the most common answers. on the other hand shows what the same companies wanted to bring back following the pandemic uncertainty. Unsurprisingly, this was also targeted at the labour they initially had to let go. This period of reactionary labour shifting caused a great deal of stress and anxiety for many of the freelancers interviewed, with some seeing their whole calendar of work disappear almost instantly. One freelancer said that this period showed a lack of understanding from both employers and the government, stating “I don’t think there’s enough understanding of freelance workers, I think COVID has shown that there’s not enough understanding of the structures, the challenges, what that might mean to your income and who’s going to be affected”. At the same time, this individual recalled a government official floating the idea that freelancers could just retrain and do something more secure which they thought “shows a naivety” regarding “what the skills are in the industry and how the industry works”. Because of this lack of understanding, it meant that freelancers failed to get the help they required, further intrenching precarity and impacts being experienced.

Emancipation through co-operation

The COVID-19 pandemic has had severe implications across the world in many forms of labour. The precarious nature of freelancing, however, has left these workers at the mercy of the coronavirus impacts much more than others. Because of the increased precarity and many of the issues highlighted by participants in this paper, it was reported that half of freelancers considered leaving the industry during the pandemic (Hickman, Citation2020). With a vast number of freelancers being unable to apply for the furlough scheme, it left them in an even more precarious position, with little job security and uncertainly as to when they will be able to go back to work and get an income to survive, which was clear when speaking to freelancers in interviews. In the videogames industry, two thirds of studios are micro-businesses, employing four or fewer people, with limited financial resources, therefore they are extremely vulnerable to sharp decreases in demand or projects (Martin, Citation2020). With many projects being put on hold, shelved, or cancelled due to lockdown, many of these micro-businesses and freelancers that work for them felt the economic impact a lot quicker than larger corporations. This was outlined by SMEs partaking in the focus group, which led them to reduce outsourced and contracted labour. These varying forms of precarity and uncertainty have contributed to concerns over freelancer wellbeing. From interviews conducted with freelancers, it is clear COVID-19 not only intensified precarity that already existed in the industry, but also added further impacts to the lives of freelance workers, as outlined in causing many workers to consider leaving the industry.

The current socio-normative top-down labour system does not provide the support for freelancers, and has enabled them to slip through the cracks, even when hired by a company to complete contract work. Therefore, it is imperative that the videogames industry diversifies and enables freelancers to operate in other corporate structures that will provide them with mental health support and alleviate loneliness. Then, if another pandemic hits in the future, workers will not be affected so badly and will have their basic psychological needs for working from home met.

Co-operative working groups provide an avenue for sustainability, however, the possibility of non-alienated labour is often dismissed by large corporations as a romanticised delusion and as a result these structures of support are then eroded, re-regulated, de-funded and downsized until they dissipate. Co-ops are often created to solve a problem and they provide a benefit to their members (Co-operatives UK, Citation2020), because of this, they can be seen as a solution to the precarity and exploitation effecting game studio workers, whether freelance or otherwise. As one co-operative member stated in interviews,

what you want a co-op to do is entirely up to you, the only thing which a co-op really needs to do is it needs to put in the maintenance just to sustain itself, it needs enough of money, and enough administration work to continue existing. Other than that, what you build its purpose as can be for anything. There are various kinds of distinctive cooperative structures.

For some, including two of the co-operatives interviewed, it was the pandemic that formed the foundation of the co-op’s purpose, opening “a possibility for more people from marginalised backgrounds” to enter the industry and start their own studios or co-operatives due to cutting away a lot of the costs previously required such as office space. This view was echoed by another co-operative interviewed, who believed that “if the pandemic hadn’t happened, [they] probably would have never started [the co-operative]”. Due to the issues outlined in this article, caused by COVID-19 and existing toxic working cultures, workers looked to alternative working models to provide the support that freelancing lacked during the pandemic, which was clear from the co-operatives interviewed. The research conducted showed that co-operatives had emancipatory potential for games industry workers, where other methods may have failed.

Huws (Citation2014, p. 78) identifies how as individual capitalist enterprises “define new protocols, performance targets and quality standards … camaraderie, idea sharing, and mutual support may become its victims”. Thus, when capitalist policies are implemented in businesses, solidarity between workers becomes unpicked and a romanticised view of being an independent worker and becoming self-employed occurs. As a result, there becomes a shift towards individualism as workers try to find a way of avoiding poor working conditions. This is especially true in the videogames industry, where freelancing is often seen as an answer to subverting the poor working conditions in the industry, such as workers believing it will help with crunch culture. However, Whitson et al. (Citation2018) argue the rhetoric that individualisation will give workers empowerment and that it produces an avenue to avoid exploitation, often fails to consider negative effects on employment conditions. Ranis (Citation2016, p. 30) notes “Despite degradations on the job, short-term workers are always expected to be of good cheer and happy in their work”. As a result of being divided and not acting as a united workforce, precarity increases as workers become dis-organised and alienated, which has been particularly apparent during the COVID-19 pandemic. Every freelancer interviewed identified problems with their way of work and have had to put up with toxic working cultures to do what they love. Additionally, a notable issue for freelancers in the videogames industry is the lack of support, even from trade unions. IWGB Game Workers, as a relatively new facet of the independent workers’ trade union, does not currently have the resources or membership to provide freelancers with the relevant support they need. When interviewed, a representative of IWGB Game Workers identified their ability to help freelancers was “very limited in scope” due to the nature of their contracts. In all the interviews conducted, when asked whether they were trade union members, it was only those who produced games music that stated they were, and they were members of the Musician's Union rather than IWGB. Freelancers didn’t know how the union could benefit them and instead went to informal groups on social media to get advice and support.

Co-operatives, which can be described as a much-neglected economic institution (Restakis, Citation2010) are currently not a common form of corporate structure in the UK. However, they offer an opportunity to confront capitalism and challenge the neoliberal economy (Ranis, Citation2016). Ranis identifies that Marxists, neo-Marxists, utopian socialists, reformed socialists and left-liberals all recognise the value and importance of co-operatives as a “counterweight to capital -worker societal relationships” (p. 1) and that they have offered a major change from hierarchy at work and working-class exploitation.

Marx also identified that co-operatives must be developed to national dimensions and as a result be “fostered by national means” (Marx, Citation1864, p. 518) in order to be fully effective against capitalism. Currently, co-operatives make up a very small proportion of the UK’s creative industries companies, with even fewer existing in the videogames industry. Whilst conducting this research, only three companies in the UK videogames industry were identifiable as active co-operatives. However, the lack of co-operatives in the games industry is, in part, because freelancer groups do not feel that co-operative models are aimed at them. A collective in Scotland, which is a collective for games industry freelancers, not an official co-operative. When asked why they didn’t form a co-operative instead, one of the directors said;

We definitely thought about it. And there were even incentives in Scotland from Scottish Enterprise to explore that at one point. But we just felt that that was more suited for a collection of businesses, as opposed to sole traders, I just felt that it asked for quite a bit. It was a bit too much. And it wasn’t very clear.

The three videogames co-operatives interviewed can be seen as examples of best practice for worker-groups in the UK videogames industry, and ergo highlights their wider utility following the COVID-19 pandemic at providing emancipation to freelancers. Workers interviewed that were part of a co-operative or collective had significantly more support than other freelancers and as a result felt less burnout, and identified colleagues felt the same way. The first co-operative interviewed was one formed of freelancers. Based in Wales, the company has thrived over the years and during the pandemic enabled workers to come together to combat many of the issues faced by the freelancers interviewed. When asked why they wanted to form a co-operative rather than a top-down games studio, they stated, “A co-operative felt like a lot more appealing to me, that flatter structure, the ability to all be working together and shoulder those kind of like burdens” Additionally, they highlighted the benefits of being in a co-operative as a freelancer;

If I walked out tomorrow and got hit by a van, and was laid up first several weeks, one of my colleagues in the co-op can step in to cover the work for me. So, there's actual value to our clients as well.

We [the co-operative] literally came from the pandemic … I realised just how important it was, lowering inequality, and I think cooperatives are a huge part of that change, and I want to actively help things.

Conclusion

The videogames industry has grown to be a critical facet of the UK’s creative industries, contributing 5.35bn to the economy per year (Ukie, Citation2019). However, in its fast rise to becoming an economic powerhouse, the videogames industry has picked up its fair share of inequalities, whether it’s AAA studios, indie studios, or freelancing. With working in indie game studios being likened to “juggling dangerous objects” (Schreier, Citation2017, p. 2), and “unpredictable, exhausting and unsustainable” (Whitson et al., Citation2018, p. 15), and freelancers experiencing inequality, insecurity and exploitation (Banks & Hesmondhalgh, Citation2009), there is an appetite for more sustainable economic models in the creative industries. There are many different forms of corporate structure, but many do not have emancipatory potential to protect workers from exploitation and inequalities which can arise in the industry. Co-operatives are a method of employment that can provide hope of emancipation.

Previous research outlines the issues experienced in the videogames industry for freelancers, primary research conducted for this paper identified 75% of freelancers interviewed were directly impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic, with the main issues being related to mental health, isolation and anxieties surrounding workflow. Thus, problems experienced before the pandemic that were characteristic of top-down labour models became compounded by COVID-19. The pandemic raised serious concerns for the welfare of freelancers in the UK videogames industry, with participants highlighting disdain with the lack of support and whether working in the games industry as a freelancer is worth the anxieties. However, those interviewed that worked in co-operatives identified a much healthier working pattern which correlates with past research highlighted by Boyle and Oakley (Citation2018). Benefits to co-op members were more emotional support for workers, the sharing round of work to ensure members do not suffer workflow-based anxieties and the ability to collectively shoulder burdens that one may face. Moreover, throughout the pandemic there was respite in knowing if they contracted COVID-19, then they would be able to claim sick pay from the business and have other members to check in on them for emotional support.

Although there are many positives to worker co-operatives, there are also obstacles, such as a lack of information on how to start them. Interviews showed a knowledge surrounding co-operatives being the main reason many freelancers had not considered them. Additionally, there are governance challenges that arise from self-management (Boyle & Oakley, Citation2018) which also arose as a criticism in interviews. However, this was seen as a minimal obstacle and that once members adjusted to a new way of working, it became a minor speedbump in the co-operative process, with positives outweighing the negatives.

This paper concurs with Boyle and Oakley’s (Citation2018) policy suggestions, particularly that there is a greater need for education, promotion and funding for those wanting to set up worker co-operatives. In the current state, they are a viable option for freelancers wanting a less precarious lifestyle, particularly following the COVID-19 pandemic where workers have been impacted in an array of different ways. The utility of worker co-ops has been shown in this research, however, the distinct lack of information surrounding co-operation makes it exceedingly difficult to break free from socio-normative corporate structures. Until policy is put in place to help workers co-operate, games industry freelancers will continue working for AAA or indie studios and be subjected to precarity, inequality and other poor working conditions.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Banks, M., & Hesmondhalgh, D. (2009). Looking for work in creative industries policy. International Journal of Cultural Policy, 15(4), 415–430. https://doi.org/10.1080/10286630902923323

- Boyle, D., & Oakley, K. (2018). Co-operatives in the Creative Industries: Think-Piece.

- Bulut, E. (2020). A Precarious Game: The Illusion of Dream Jobs in the Video Game Industry. Cornell University Press.

- Co-operatives London. (2020). London’s Co-ops – Co-operatives London. [online]. https://ldn.coop/londons-co-ops/

- Co-operatives UK. (2017). Simply Legal. 3rd ed. [PDF] Manchester: Co-operatives UK. https://www.uk.coop/sites/default/files/2020-10/simply-legal-final-september-2017.pdf

- Co-operatives UK. (2020). A Guide to Co-ops. 1st ed. [PDF] Co-operatives UK. https://www.uk.coop/sites/default/files/2020-09/Welcome%20Guide_Public.pdf

- Emelianoff, I. (1942). Economic Theory of Cooperation. 1st ed. Davis: Center for Cooperatives, University of California.

- Green Worker Cooperatives. (2022). Co-op Academy New York. [online]. https://www.greenworker.coop/coopacademy

- Hansen, M., Morrow, J., & Batista, J. (2002). The impact of trust on cooperative membership retention: Performance, and satisfaction: An exploratory study. The International Food and Agribusiness Management Review, 5(1), 41–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1096-7508(02)00069-1

- Heinman, D. (2015). Thinking About Video Games: Interviews with the Experts. Indiana State Press.

- Hickman, A. (2020). Coronavirus Impact: Half of Freelancers Consider Quitting and Have Lost at least 60 Per Cent of Income. [online]. Prweek.com. https://www.prweek.com/article/1679652/coronavirus-impact-half-freelancers-consider-quitting-lost-least-60-per-cent-income

- Huws, U. (2014). Labour in the Digital Economy. Monthly Review Press.

- International Co-operative Alliance. (2021). Our History. [online]. https://www.ica.coop/en/cooperatives/history-cooperative-movement

- Jenson, J., & De Castell, S. (2013). Tipping points: Marginality: Misogyny and videogames. Journal of Curriculum Theorizing, 29(2), 72–85.

- LaLonde, M. (2020). Behind the Screens: Understanding the Social Structures of the Video Game Industry [Electronic Theses and Dissertations]. Paper 3727. https://dc.etsu.edu/etd/3727

- Lipkin, N. (2013). Examining indie’s independence: The meaning of “indie” games: The politics of production, and mainstream cooptation. Loading, 7(11), 8–24.

- Martin, A. (2020). Coronavirus: Lockdown Isn’t The Windfall You’d Expect for the British Games Industry. [online]. Sky News. https://news.sky.com/story/coronavirus-lockdown-isnt-the-windfall-youd-expect-for-the-british-games-industry-11970375

- Marx, K. (1864). Inaugural Address of the International Working Men’s Association. London. https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1864/10/27.htm

- Mould, O., Vorley, T., & Liu, K. (2014). Invisible creativity? Highlighting the hidden impact of freelancing in London’s creative industries. European Planning Studies, 22(12), 2436–2455. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2013.790587

- New Economics Foundation. (2018). Co-operatives Unleashed. https://neweconomics.org/uploads/files/co-ops-unleashed.pdf

- Orsini, C., & Rodrigues, V. (2020). Supporting motivation in teams working remotely: The role of basic psychological needs. Medical Teacher, 42(7), 828–829. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2020.1758305

- Perotin, V. (2016). What Do We Know about Worker Co-operatives? Co-operatives UK. https://www.uk.coop/sites/default/files/uploads/attachments/worker_co-op_report.pdf

- Ranis, P. (2016). Cooperatives Confront Capitalism: Challenging the Neoliberal Economy (1st ed.). Zed Books.

- Restakis, J. (2010). Humanizing the Economy: Co-Operatives in the Age of Capital. (1st ed.). Post Hypnotic Press.

- Santava. (2020). Game on: a study of UK gaming attitudes and behaviours. [online]. https://info.savanta.com/uk-gaming-attitudes-and-behaviours

- Schreier, J. (2017). Blood, Sweat, and Pixels (1st ed.). Harper Collins.

- StoryFutures. (2021). Our business network - StoryFutures [online]. https://www.storyfutures.com/creative-cluster/business-support/our-business-network

- The Employee Ownership Association. (2017). The Impact Report. http://employeeownership.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/The-Impact-Report.pdf

- Ukie. (2019). 2019 UK Consumer Games Market Valuation. [online]. https://ukiepedia.ukie.org.uk/index.php/2019_UK_Consumer_Games_Market_Valuation

- United States Department of Agriculture. (1994). Understanding Cooperatives: Cooperative business Principles. [online]. https://www.rd.usda.gov/files/CIR45_2.pdf

- Whitson, J. R., Simon, B., & Parker, F. (2018). The missing producer: Rethinking indie cultural production in terms of entrepreneurship: Relational labour, and sustainability. European Journal of Cultural Studies, 24 (2), 606–627. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367549418810082

- Woodcock, J. (2019). Marx at the Arcade: Consoles: Controllers, and Class Struggle. Haymarket Books.

- Zeuli, K. A., Cropp, R., & Schaars, M. A. (2004). Cooperatives: Principles and Practices in the 21st Century.