ABSTRACT

This article investigates the issues and tensions involved in collecting data from audiences to describe their diversity. It uses data collected as part of a survey of festival audiences to examine (1) how people choose to describe their identity in an open-text question and (2) how classifying complex responses to questions about ethnic or cultural background has implications for analysis. First, data provided through an open-text question in the festival survey were used to establish two classification systems. The results show patterns in the relationship between how people choose to identify themselves and their arts knowledge and appetite. It also shows patterns between what they identify about themselves and their arts knowledge and appetite. The article helps researchers better understand the implications of providing open opportunities for audience members to report the way they choose to see themselves, and of establishing classification systems based on this data for analysis.

Introduction

The government expects all museums, theatres, galleries, opera houses and other arts organisations in receipt of public money to reach out to everyone regardless of background, education or geography (DCMS Citation2016, p. 23).

This article takes research that the authors conducted with audiences at a Melbourne Asian-themed festival in 2017 as an opportunity to investigate the difficulties involved in seeking data about culture/ethnicity in particular. As is described below, Australian governments prefer the term Culturally and Linguistically Diverse (CALD) to “ethnicity”, and this nomenclature was adapted for the research as the term “cultural background”, in preference to alternatives. What became evident to the researchers over the course of their research was that research participants wanted to describe their identity in different ways to those that the producers of the festival were seeking, and this article responds to that discovery. The article begins by discussing the difficulties of data collection, analysis and reporting about culture/ethnicity that researchers have identified. It examines critiques of the approach that government agencies and arts sectors have taken to the task of understanding the cultures and ethnicities of their audiences. It then describes an audience survey the research team conducted during the 2017 festival in which a single question was asked to identify cultural diversity, and discusses its results. In doing so, the article investigates not just what audiences reported about their cultures/ethnicities and how these intersected with their experience of the festival events, but also how they chose to answer the question of culture/ethnicity, and how the way survey respondents chose to answer intersected with their experience of the festival events. The article compares two ways of classifying demographic data – one that is informed by how people chose to respond, and a second that builds on the first to focus on what they self-reported. The article compares these two systems to examine the relationship between how people responded to the question and their experience of an arts event. The analysis found patterns not just between what cultures/ethnicities people reported (e.g. European) and their arts activity and interest, but it also found patterns between how they reported these and their arts activity and interest.

The researchers were commissioned by a consortium of arts organisations to evaluate an inaugural Asian-themed festival the consortium had programmed. The objective of the evaluation was to provide information the consortium could use to report to the Federal and state government funding and philanthropic agencies that had funded the festival. Several consortium organisations were interested in attracting Asian Australians and tourists from the Indo-Pacific to Melbourne’s major arts organisations, as these groups have historically been under-represented (Gill, Citation2016). These producers were keen to see that the introduction of Asian themed programming, where previously there had been little by Melbourne’s major arts organisations, would influence the demographic profile of audiences.

The data collection challenges of ethnicity and cultural background

The terms “race”, “nationality”, “ethnicity” and “cultural background” overlap significantly and have different definitions and currency in different national contexts. Australian government agencies prefer the unique term “Culturally and Linguistically Diverse (CALD)” to alternatives. The term CALD was introduced by the Australian Bureau of Statistics in 1999 as “a broad concept drawing attention to both the linguistic and cultural characteristics of multicultural populations living in Australia” (Pham et al., Citation2021, p. 738), and is a result of a complex history of contested terminology for identifying difference. Following the waves of migration to Australia after the Second World War, the Australian Government adopted a range of designations for immigrants, including “New Australians” and then “Australians of non-English-Speaking Background” (Danforth, Citation2001, p. 367). Danforth notes that such designations, in practice, constituted “a system of cultural categories distinguish[ing] between people who are Australians and people who are not Australians by excluding all those who are ethnically marked from the national community of Australians. More specifically this system of categories establishes an opposition between ‘Australians’ … and ‘ethnics’ or even more colloquially between ‘Skips’ and ‘Wogs’” (Danforth: 367).

The development of the term CALD, then, can be seen as a response to earlier designations which effectively placed the term “ethnic” in opposition to the idea of “Australianness” and excluded from the category of “Australians”. Even if the terms were not seen to be in active opposition, they nonetheless reinforced the idea that “ethnic minorities are still guests in our midst” (Burchell, Citation2006).

In the study of the Asian-themed festival, the researchers used the term “cultural background” in the survey as a strategy to make a rhetorical connection to the current official terminology of CALD, avoiding the historically negative or oppositional terminology of “ethnic”. In the following discussion of internationally sourced literature, however, we acknowledge Brubaker et al’s (Citation2004) argument that the different terms for cultural and ethnic origins may need to be treated as one. In recognition of its international readership, discussion of the literature here employs the term “culture/ethnicity”.

As the imprecision around what constitutes ethnicity and cultural background suggests, different approaches to collecting and classifying data on cultural background each have their own methodological advantages and disadvantages. These issues apply both in terms of what the research seeks to find and what participants seek to convey. For example, research methods that ask respondents to nominate skin colour (e.g. White or Black), race or nationality have been criticised for the fact that these categories do not indicate culture or ethnicity (Aspinall, Citation2012, p. 356). Similar skin colour may apply to a range of cultures and indicates only appearance, while nationality is easily conflated with citizenship.

Furthermore, ethnicity is a fluid and socially constructed concept that varies according to the context in which it is reported (Williams & Husk, Citation2013). For Merino and Tileagă (Citation2011), social identities represent “discursive accomplishments” – a feature of how people describe themselves “with reference to indexical and interactional work performed in the context of social science research interviews” (Citation2011, p. 87). Wetherell (Citation2009) notes the discursive “accomplishment” of social identity happens when people are “multiply called upon, categorised, classified, registered, enrolled, and enlisted often in highly contradictory and antagonistic ways” (Citation2009, p. 4). Identity formation involves the ongoing “work” of “forming and dismantling, claiming, reminding, identifying, re-establishing and rejecting” (Citation2009, p. 4). This “work” involves “approaching identity ‘making’ and ‘doing’ as a public and discursive phenomenon, contingent on local and contextual conditions of production” (Wetherell, Citation2009, p. 4). Indeed, Merino and Tileagă argue that ethnic minority identity “needs to be ‘done’ over and over again” (Citation2009, p. 89). These insights about identity formation have been borne-out to some extent in our findings. Some respondents, as outlined below, provided narrative accounts of their cultural backgrounds, thus bringing their self-identification “to life” by incorporating aspects of their lived experience.

Crucially, the frequent and rapid human mobility that has characterised the late twentieth and twenty-first centuries means that cultural background is often more complex than research methods such as surveys can easily accommodate. Kymlicka (Citation1996) used the term “polyethnicity” to describe the fact that individuals themselves often have multiple cultural backgrounds, while Vertovec (Citation2007) coined the term “superdiversity” to indicate the complexity of societies shaped by multiple generations of migration and exogamy (e.g. Alba et al., Citation2018). Polyethnicity and superdiversity have implications for survey design (Prewitt, Citation2018). Questions that require respondents to select only a few options for their ethnicity or cultural background require them to make judgements about the value of the different components of their identity (Alba et al., Citation2018). Predetermined options in a survey question are either more limited than the many hundreds of ethnicities identified across the nation or world (Deaux, Citation2018), or – should they offer a suitably representative number of options – “would likely invoke respondent burden and complexity at the cost of practicality and possibly precision” (Aspinall, Citation2012, p. 358).

Polyethnicity is therefore in tension with the term “CALD”, which implicitly identifies only two groups: the culturally and linguistically diverse group, and “non-diverse” people. A key challenge in the Australian policy context is whether or not polyethnic descriptions include “Australian”; for example, “Asian-Australian” compared with “Asian”. The term “Asian-Australian” is widely used in an arts and culture context (for an overview, see Fairley, Citation2016), although there is a lack of clarity about under which circumstances someone might describe themselves with or without the hyphenated term: the term is not used to distinguish “new Australians” from subsequent generations of Asian descent (for example, Matthews, Citation2002). Chu et al’s (Citation2017) study of an Asian minority sample living in Australia investigates whether they identify more closely with the term “Australian”, a term associated with their background, or a hyphenated term: overall, people’s preferences are slightly stronger for the hyphenated term, but without any clear trends in any direction. This extends beyond people who might be described as “Asian-Australian”: Gebrekidan (Citation2018) investigates use of the term “African-Australian”, where some respondents with similar migration trajectories state that they use the term, while others reject it, stating that they would never describe themselves with a term that includes “Australian”.

In recognition of the complexity of cultural identity and sensitivities around questions of identity, demographic surveys often include open text questions to allow respondents to describe their identity on their own terms (Aspinall, Citation2012; Oman, Citation2019; Prewitt, Citation2018). These questions allow respondents to enter text freely into a box, rather than selecting one or multiple options from a preselected list. Such answers “can offer a more contextual rendering of … lived experiences” (Oman, Citation2019, p. 5). Responses to these questions can illuminate how respondents view their own ethnic/cultural identities, in turn providing researchers with more nuanced information (Burton et al., Citation2010). The use of open text in social surveys can also improve perceptions of the acceptability of this question to respondents, and improve response rates (Connelly et al., Citation2016, p. 2).

Open text questions also have limitations, both practical and ideological, particularly when it comes to analysis. Because respondents present information in very different ways, open text questions are harder to classify. If responses are accepted simply as given, they are likely to present a large number of small categories, in ambiguous relation to one another. If – as is more likely – researchers classify the responses into a smaller number of categories, they are doing covertly what the predetermined menu question does explicitly: collapsing respondents’ complex identities into manageable but not necessarily authentic categories (Aspinall, Citation2012). As Alba et al. (Citation2018) argues, even the treatment of predetermined menu choices can be oversimplified in post-survey classification, resulting in misleading reports. This is exacerbated where researchers classify the vastly wider range of open text responses. The open text question also presents a practical challenge as the classification process is likely to be time consuming and therefore costly, due to the need for post-survey interpretation. However, a crucial advantage is that classification can be adapted according to the purpose for which it is intended (Prewitt, Citation2018).

The article aims to investigate the properties that Alba and Prewitt identify in relation to open text questions to identify culture/ethnicity. Returning to the context of an Asian-themed arts festival, researchers anticipated that asking audience members to choose from a preselected list of national cultures (e.g. Chinese, Malaysian, Italian) and combinations (e.g. Chinese-Italian) would make for a laborious task in the time afforded by a theatre interval, while collapsing nationalities into categories (e.g. Asian, European) would risk “monolithising” audiences (Conner, Citation2022, Odom & Raghunathan, Citation2022, p. 97) and prevent them from describing their identity with precision. In addition, the relatively small number of responses the researchers anticipated – which based on ticket sales would be fewer than 500 – meant that establishing categories from qualitative data would not be overly onerous. Finally, as the research process progressed, the researchers became interested in using the survey delivery to examine not just the cultural background and festival experience of audience members, but also how different systems for classifying the resulting data could affect the findings on the relationship between cultural background and festival experience that resulted from the survey.

The research challenges involved in collecting audience data

If asking questions about culture/ethnicity is fraught with complexity, doing so in a theatre foyer only adds to the complexity. This is due to the complex and highly politicised relationship between cultural activity and social identity, discussed in this section, as well as pragmatic reasons, discussed in the next.

Following Bourdieu (Citation1979), sociologists note the ways in which people’s tastes are informed by intersecting demographic factors such as class, gender, education and ethnicity (e.g. Callier & Hanquinet, Citation2012; Schaap & Berkers, Citation2020). Cultural studies and cultural policy research shows that public discourse and public policy have consistently bestowed value on the preferences of white, wealthy and educated classes over others (e.g. Meghji, Citation2019; Sedgman, Citation2018). Historically, this has been enabled by art historians, theatre scholars, cultural policy-makers and arts critics simply assuming that their own experiences as audience members are reflective of the whole audience, rather than investigating what diverse audiences actually experience in a performing arts event (Freshwater, Citation2009). Contemporary researchers seek to address this failure, providing research that supports an agenda of democratisation in the funding and representation of different kinds of cultural pursuits.

However, the relationship between audience research and the democratisation process is not straightforward. Conner (Citation2022) points to the use of audience data collection to inform key arts organisation processes as maintaining a racially exclusive status quo in publicly-funded performing arts, justified by the preferences of their existing audiences. Although arts organisations commonly claim to want to diversify their audiences, their strategies rarely seek to “effectively understand all the ways that audience members differ from one another, both in terms of their identities and in terms of what they seek from an audience experience” (Conner, Citation2022, p. 59). Both Conner (Citation2022) and Ashton and Gowland-Pryde (Citation2019) take arts organisations’ use of audience segmentations to illustrate how orgnisations reinforce value judgements about audiences with different demographic characteristics.

If the ways in which arts organisations collect and analyse audience data around culture/ethnicity is fraught, so too is the way in which government agencies collect sector-wide audience data. As Noble and Ang (Citation2018) have argued, cultural policy has given ethnicity minimal attention in the past, and “what attention there is displays crude assumptions” (Citation2018, p. 298). To illustrate such assumptions, they point to the Australia Council’s national arts participation survey, Connecting Australians. In order to estimate the diversity of the arts audience, this survey asks respondents “Do you identify as a person from a culturally or linguistically diverse background?”, with the possible responses of “Yes” and “No”. By grouping all culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) people into one category, this question constructs a “questionable separation of mainstream and non-mainstream people” (299), reminiscent of the distinction Conner identifies between “western/non-western” audiences and the distinction Danforth identifies between “Australians” and “ethnics”. Having only two, polarised options (Yes/No) also means that respondents are not able to answer in a manner consistent with Wetherell (Citation2009) and Williams and Husk’s (Citation2013) points that ethnicity is fluid, and contingent on contextual conditions.

Noble and Ang draw attention to significant differences in cultural consumption between different ethnic groups – all of whom would be classified within the broader CALD group. Like Conner (Citation2022) and Ashton and Gowland-Pryde (Citation2019), they argue that this means “we should avoid lumping together ‘multicultural Australians’ to address the ‘problem’ of ethnic under-representation in cultural consumption” (Noble & Ang, Citation2018, p. 302). Walmsley asserts that audience researchers need to provide opportunities for audiences to express their inter-subjectivity, to “think aloud” about themselves as a way of liberating “subjugated knowledge and multiple realities” (Citation2018, p. 277). This critical lineage behind the current research reinforced the need in the research we conducted to give audience members the opportunity to define their own cultural identity in the specific context of a theatre performance. The open-text question provided a means of doing so.

Surveying the festival audience

As part of the research with the Asian-themed festival, data were derived from an audience survey (N = 435) of attendees at five festival events. One organisation, representing the consortium, commissioned the research. The research objectives were developed by the commissioning agency in discussion with the researchers. The researchers briefed the contact organisation about its research methods, including the survey, but the consortium did not contribute to the survey design or implementation. The 5 events were selected because they represented a range of artforms (folk music, contemporary dance, experimental performance, classical music and ballet) in a range of venues (for example an arts centre, a gallery foyer and a concert hall), and so were regarded as representing the breadth of audiences across the festival.

The survey included questions about audience demographics, motivation to attend, response to the performance and attendance at other festival events. The surveys were conducted in the foyers of the theatre spaces of each of the 5 events, and involved both the researchers and trained volunteers approaching attendees – on a random basis – either at the interval or at the end as they exited the foyer. The survey took approximately 10 min to complete, and responses were collected during the interval. Five to eight student volunteers under staff supervision approached audience members at each event, until they had exhausted the number of willing participants. Volunteers used electronic tablets to implement the survey and record responses. The 435 survey responses represented approximately 10 per cent of the total number of people who attended the performances. Limitations of the collection of data in interval include the possibility that respondents may have felt rushed and/or prevented from the activities an interval usually affords attendees, and the potential for sampling bias as audience members who remained in the auditorium during interval were not captured.

The survey asked 3 questions about the demographic characteristics of the respondent, followed by a series of 12 questions about their experience of the performance. Specifically, we asked the question: “What is your cultural background?” rather than “ethnic background”, consistent with Australian governments’ preference for cultural and linguistic diversity over ethnicity, as described above. People could and did respond to the question in a range of ways. Some of these fit cleanly with the festival producers’ goal of measuring the proportion of audience members with Asian backgrounds: 28% of respondents either used the term “Asian” or named a specific country in Asia; 14% named a specific country in Europe. A further 10% of responses, while less specific, provided a clear indication that respondents did not consider themselves Asian, such as “Western”, “Anglo-Saxon”, or “White”. The researchers classified responses into two categories – Asian and non-Asian – to meet the programming consortium’s objective for the research. Here, however, we use the same data to develop alternative classification systems to better analyse how respondents engaged with the question they were asked.

Illustrating broad categories

In reading survey responses, researchers were struck by differences in how respondents interpreted the question and the task required to answer it, and therefore in how they responded. Responses ranged from simple (such as a single word) to complex (a narrative account of significant factors constituting their cultural background), and from thorough (the narrative account) to cursory or avoidant. An initial coding exercise defined five broad categories of responses in a way that differentiated between approaches to answering the question rather than the answers themselves. Once definitions for each category were established, two researchers coded the data independently of one another and cross-checked the results. Their results deviated by under 1%, with three responses classified differently. The categories are significantly different in number of responses, with just one category encompassing a (slim) majority of respondents. The numbers in each category are given in . In this section, we briefly describe these categories. The categories were then used as the basis for two classification system, which are described in the following section.

Table 1. Classified responses to “What is your cultural background?”

Australian: Results in this category included the use of the descriptor “Australian” or derivatives of that adjective (“Aussie”, “OZ”) and terms referring to Australian First Nations people. The category also included qualifiers used to indicate the respondent was white, such as: “Anglo Australian”, “White Australian” and “White Settler”. Where “Australian” was qualified by ethnicity signifiers, respondents did so by attaching a descriptor of their national background, for example: “Macedonian Australian”, “Australian Sri Lankan”.

Nation Specific (non-Australian): The second category was defined by the identification of a nation other than Australian, such as “Lithuanian”, “Thai”, “Maori”, “Greek”, Chinese. Whether these identifiers denoted birth, nationality or ancestry was not stated.

Non-specific: This category was defined by its lack of specificity and adoption of normative assumptions. These respondents did not indicate a place or location for their ethno-cultural background but instead used general (non-national, but in some cases regional) descriptors signalling their “whiteness”, such as “Anglo Celtic”, “Anglo Saxon”, and “European”. Some respondents used phrases such as “White as white bread”; “White and boring”, and “Whitey” to suggest that they had read the question as a code for ascertaining racial attributes. Williams and Husk (Citation2013, p. 297) argue that “the ubiquitous ‘white’ category often remains proxy for ‘no ethnic affiliation’”. Indeed, many respondents simply answered “None”. A smaller number of audience members described themselves simply as “Asian”.

Narrative: This category was defined by respondents’ efforts to explain a complex background that included their experiences as well as their country of birth, ancestry or appearance. For example, “Anglo but lived several years in various countries including southeast and south Asia”; “I come from Indonesia but I was born in Malaysia”. As noted by Williams and Husk, ethnic identity may comprise only a small part of the composite identity of the individual, and “for some may be closer to what Herbert Gans (Citation1979) identified as ‘symbolic ethnicity’ of the kind he found amongst third-generation Americans who identified with their (for example) Jewish or Italian heritage” (Citation2013, p. 290).

Resistance, Refusal: This category is defined by respondents’ hostility or resistance to answering the question, or their interpretation that it was asking about a different kind of “cultural background” to ethnic-cultural background. Some people used terms to signify their cultural capital: “Beer and chips”; “Overeducated”; “artist”; “PhD in cultural studies”. These responses can be seen to suggest that people read the term “cultural background” to mean how they identified in terms of sub-cultural groups or activities. Some respondents were resistant to participating, or refused entirely. One respondent wrote “None of your business”; another “Stop trying to put Asians in one box”.

*

Alternative classifications: construction

The broad categories established above identified approaches to the question rather than answers to it; these broad categories were not helpful for the initial focus of the research, which was to estimate the proportion of Asian attendees at festival events. That is because the categories that include either individual countries or regions in Asia – “Nation-specific” and “Non-specific” – also capture other parts of the world. For this reason, we make distinctions within the “Nation-specific” and “Non-specific” categories between different parts of the world. This process, though, is not neutral: the processes of coding categories (as above) and of forming subcategories both involve human judgment. In this section, we describe how the process of classifying different, complex responses to questions about people’s cultural background may have implications for activities such as evaluation.

summarises the numbers of people in each of the five broad categories described above. We initially distinguished within the Australian, nation-specific, and non-specific categories, across different global regions: for example, distinguishing between people within the “Australian” category who responded only with “Australian”, and those who combined this with another classification (e.g. Australian/Chinese). This allowed us to distinguish people who responded to the question with an individual Asian country or region, or with the continent more generally. It also distinguishes those people whose responses indicated that they were First Nations people from Australia and New Zealand (a small number). In the first classification, people who offer nation-specific backgrounds are grouped according to regions: European, Asian, and “Other”. The use of an “Other” category is problematic, because by definition it “others” or simultaneously lumps together and excludes the diverse people grouped into it; it has been used because the numbers of people who offered nation or region-specific responses other than Europe and Asia was small.

The challenge associated with this approach is classifying people who described their cultural background with hyphens. Should someone who answered “Chinese-Australian” be classified as “Asian”, “Australian”, or something else? Our interpretation of the literature in this field suggests we should not group them into the “Australian” category: however, it is not clear whether we should group them with the “Asian” category or form a distinctive category. For this reason, we analyse the data using two separate classifications. In “Classification A”, we include people who provided hyphenated descriptions that included “Australian” into the category associated with the other component of their answer (e.g. “Chinese-Australian” is included in “Asian”); in “Classification B” we introduce new categories acknowledging these responses, such as “Asian Australian”. This distinction is particularly relevant in the context of an Asian arts festival: the use of a single “Asian” category may mask significant differences within it.

shows that the most common responses, with 93 each, were those that were Australian only and nation-specific Asian. Only 8 audience members provided narrative responses, while 20 provided resistant responses.

These classifications have implications for how an audience might be described. As a simple example in this particular context, the Asian audience might be estimated as the number of people who responded only with an Asian country or region (24%), or alternatively it might also incorporate those people who described themselves as Australian, combined with an Asian country (an additional 4%). The latter option is consistent with the intentions of the festival consortium, which sought to attract more of both categories of audience, without necessarily distinguishing between them.

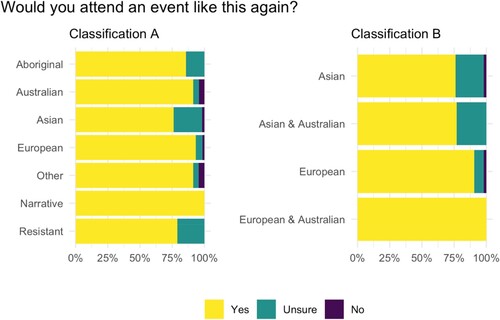

These classifications also have implications for how differences between groups are interpreted. We illustrate this by examining the answers that audience members provided to three other sets of questions. As part of the broader questionnaire, audience members were asked “How familiar were you with the content of this performance?”, and “How familiar were you with the culture of this production?” prior to their attendence, on a six-point scale from “not familiar at all” to “very familiar”. They were also asked whether they had attended any other festival events, and any other arts events in the previous twelve months; and whether they would attend an event like the festival again. As shown in , we focus on these questions as they each encapsulate different elements of audience research: audience members’ knowledge, captured by the first two questions; their frequency of attending events, captured by the second two questions; and their satisfaction from the event, captured by the final question. If audience research aims to understand the differences on these items between different groups, then the way that groups are constructed matters.

Table 2. Survey questions in relation to research topics.

Alternative constructions: implications

shows how questions that report on audience members’ knowledge, by giving them the opportunity to rate their familiarity with the content of the performance and the culture behind the production, vary by the different categories of cultural background and according to the two different classification systems. In this figure, we report the results for all categories within Classification A; within Classification B, we report the results for the four groups that are different from their counterparts in Classification A.

Figure 1. Familiarity with the culture and content of this performance, by different categories of cultural background and classifications.

Across all four panels, we can see that the “Narrative” group was most likely to highly rate their familiarity with both the culture and the content, with everyone in this group rating themselves a minimum of 2/5, and nearly half of this group rating themselves with the maximum score for their familiarity with the culture behind the production. In contrast, we can also see that the “Resistant” group, while engaging with the question of cultural background more confrontationally, are not significantly different from the “Australian”, “Resistant”, and “Other” groups in terms of their familiarity.

The value in building from Classification A to Classification B comes out vividly on these questions. The two “European” groups are fairly similar to each other; on balance, the “European and Australian” group rates its familiarity slightly higher than the “European” group, but with small differences. By contrast, members of the “Asian” group describe themselves as vastly more familiar with both the content and the culture than the “Asian & Australian” group. While in Classification A the “Asian” group reports similar familiarity to the “First Peoples” and “Other” groups, and lower familiarity than the “Other” group, this masks the crucial difference that the less familiar ratings were predominantly from those respondents who included the descriptor “Australian”.

therefore highlights a number of differences between groups in terms of their existing familiarity with performances. It shows how the groups who engaged more discursively around the question of their cultural backgrounds – the “resistant” group confrontationally, the “narrative” group indirectly – report very different familiarity. The “narrative” group perform their expertise through their answers about their cultural background and extend this performance through their claimed familiarity. This shows the value of this category for what it tells us about survey responses. It is not a category that provides information about its occupants’ cultural background; what it does suggest is that people who wish to provide a long-form answer do so in order to show their relationship to the subject in question. In contrast, the resistant group is very similar to other groups. These other groups, offering more direct responses to the question, look very different depending on the classification – those with “European” descriptors are similar in their familiarity to those who simply describe themselves as “Australian”, whether the “Europeans” include the term “Australian” or not, while there are major differences within the “Asian” category between those who used the “Australian” descriptor and those who did not.

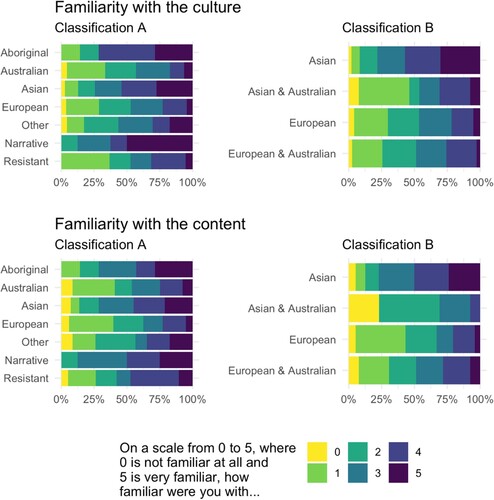

shows whether audience members have attended any other festival events (upper), and any other arts events (lower), in the previous 12 months.

Figure 2. Attendance at other festival events, and other arts events, by different categories of cultural background.

As described above, the festival audience is highly-engaged in cultural events, with 81% having attended at least one other arts event in the previous twelve months. Again, however, the choice of classification has implications for how this is interpreted.

Once again, the “Narrative” group is very distinctive: half its members have attended another festival event, compared with 29% of the overall sample. However, they are less distinctive in terms of their overall arts attendance on this measure, with large majorities of each group – again, including the “Resistant” group – having attended other events.

The lower two panels of illustrate further important differences. In Classification A, we can see that the “European” group is the most likely to have attended other arts events in the previous 12 months, while the “Asian” group is the least likely. While the four groups distinguished by Classification B are equally likely to have attended other events as part of the festival, within the “Asian” group, people who included the “Australian” descriptor were about half as likely to have not attended any other arts events in the previous twelve months. To put it another way, the distinctiveness of the “Asian” group in Classification A is entirely driven by people who did not use the “Australian” descriptor; those who did use it are about as likely to have attended other arts events in the previous twelve months. The pattern is similarly pronounced for the “European” group: a larger fraction of the group that also used the “Australian” descriptor attended an event in the last twelve months than any other group.

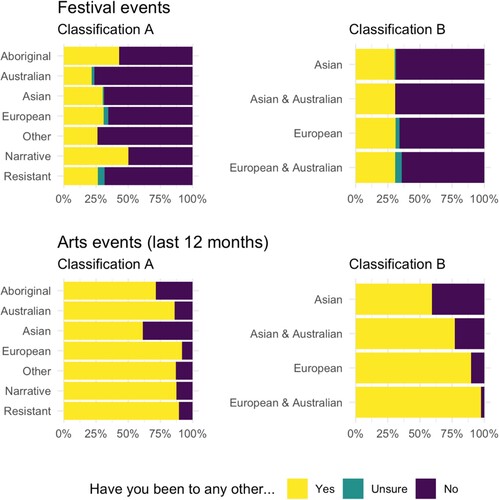

Finally in this section, shows which audience members stated that they would attend an event like this again.

In this case, the “Asian”, “Resistant”, and “Narrative” group are the most distinct. Every single member of the “Narrative” group would attend an event like this again; the “Resistant” and “Asian” groups have the largest fraction of people who aren’t sure.

While in the previous questions the distinction between those people in the “Asian” group who did and did not use the “Australian” descriptor entailed large differences, in this case it makes almost none: members of both groups are about as likely as each other to report that they’re unsure whether they would attend a similar event again.

Taken together, we can see a set of patterns emerging. The “Narrative” group report that they know a lot about the culture behind the production, and about the performance itself. Most of them are regular arts attenders, they’re the most likely to have been to another festival event, and all of them would go to another event like this one. The “Resistant” group may not be experts in the performance, or the culture behind it, but they’re no more or less knowledgeable than the average audience member, nor are they any more or less regular attenders; slightly more of them might not come back.

In moving from classification A to classification B, breaking apart the “Asian” and “European” categories reveals crucial differences within them. On the questions we discuss, patterns of responses among the two “European” categories are very similar to one another. Like the Resistant group, they may not be experts in the performances at the festival, but they’re regular arts attenders and almost all of them would come back, especially those describing themselves with the descriptor “Australian”; they closely resemble a traditional arts audience. The “Asian” group, already distinctive in Classificaiton A, conceals much more internal heterogeneity than the “European” group. The respondents who include the descriptor “Australian” are much less familiar with both the content of the production and the culture behind it, but are more likely to be regular arts attenders. At the same time, those people in the “Asian” group, whether using the “Australian” descriptor or not, are the least likely of all groups to state that they’d attend another similar event.

*

Discussion

The importance of classification

The use of the open text box led to detailed responses suggesting that the question spoke to issues of self-definition and identity politics; the question elicited not just “where am I from?” but “who am I?” Certainly the descriptor “Australian” was frequently used but inflected with a sensibility around race and “whiteness”. Reflecting Williams and Husk’s (Citation2013) comment that ethnicity is socially constructed, this sensibility is no doubt a reflection of the particular post-colonial context in which Australian-ness is constantly contested or under negotiation.

Where other answers to “Australian” were given, they signalled greater complexity. The term “Asian”, while of significant symbolic value to the producers of the festival, was only used by three respondents. Porter et al. notes that within health research the widely practised habit of aggregating data into statistically manageable units, for example the practice of combining countries of birth or ethnicities into collective groups such as “Asian”, is “commonly practiced” but “of questionable utility”, (Porter et al., Citation2016, p. 169). When “Asian” collapses together those respondents who see themselves as Asian Australians with people who identify only non-Australian Asian cultures in their background, it obscures important differences between these two sub-categories. Further, the hoped for “manageable units” of data was undermined by respondents – particularly those in the “Narrative” category – choosing to give complex answers with multiple qualifiers including: ancestry, race, religion, birthplace, and length of time living somewhere. These multiple qualifiers are all expressions of the kinds of “superdiversity” that Vertovec (Citation2007) identifies, taking into account not just ancestry but lived experience. In a context of an Asia-themed Australian festival where audience diversity and curiosity about cultures are encouraged, it is less likely that respondents wish to truncate or gloss over the specific national or cultural details of their complex identity, and more likely that they wish to assert them (Chu et al., Citation2017). Moreover, as Classification B showed, any summary data based on an overall “Asian” group, which may have been the festival programmers’ anticipated goal, would mask significant variation within that category, with respondents who used the term “Australian” being very distinctive from those who did not on two key measures: their knowledge and frequency of audience membership, if not their satisfaction.

By asking the question “What is your cultural background?”, the survey participated in the process of calling upon audiences to wrestle with the discursively complex business of articulating an identity for the purposes of categorisation and classification. Merino and Tileagă’s (Citation2011) argument that identify formation is a function of belonging to particular social groups and shaped in relation to their interaction with their context was most evident for us in those responses that aimed to signal cultural identity in the Narrative category, by those who elected either not to give a country of origin, or not just to do so but to also indicate where the respondent’s life path was seen to contribute to their sense of a cultural self. These responses demonstrated respondents’ appetite for “liberating subjugated knowledge and multiple realities” in the way that Walmsley advocates for (Citation2016). In addition, the respondent who gave the answer to the question of cultural background as “Who’s asking?” neatly illustrated the importance of contextual conditions and relationships to how one decides what to answer (Wetherell, Citation2009).

Conclusion

This article used a single open-text question in a survey about the cultural characteristics of performing arts audiences, to turn the reader’s attention not to the results of that survey, in the sense of the demographic composition of the audience, but rather to a close observation of the way that respondents choose to respond. For some the answer was a simple one because they identified with a perceived norm as white Australians, or as simply “white”, untethered to any specific nationality or culture. A significant number of respondents provided narrative accounts to explain aspects of their identity. We classified these responses to show patterns in the relationship between people’s description of their identities and their arts knowledge and appetite. We have demonstrated that the way that data are classified can significantly change the conclusions drawn from that data.

There are implications for both arts/cultural sector organisations and researchers from this research. For organisations, the issue of how diversity is understood is key. This current research suggests that, rather than seeking to classify the diversity of audience members into “manageable units” of data (say “Asian”), organisations could consider taking a more nuanced approach – one that recognises that their audience members may benefit from an opportunity to choose how they describe themselves, not only in terms of their identities but also what they seek from an audience experience.

For audience researchers, this paper underlines the limitations of surveys in collecting and classifying identity data. As discussed above, in the context of “polyethnicity” and “superdiversity”, survey design must recognise the limitations of predetermined options. Where responses to open-text questions are grouped, research should consider how such categorisation may reflect the results. While we have acknowledged the limitations of the open-text question, it remains a valuable opportunity for audiences to “think aloud” about their cultural identity and their cultural experiences as audiences.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Alba, R., Beck, B., & Sahin, D. B. (2018). Parentage: A sociological and demographic phenomenon to be reckoned with. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 677(1), 26–38. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716218757656

- Arts Council England. (2018). Equality, Diversity and the Creative Case: A Data Report, 2016-17. Manchester.

- Ashton, D., & Gowland-Pryde, R. (2019). Arts audience segmentation: Data, profile, segments and biographies. Cultural Trends, 28(2–3), 146–161. https://doi.org/10.1080/09548963.2019.1617938

- Aspinall, P. J. (2012). Answer formats in British census and survey ethnicity questions: Does open response better capture ‘superdiversity’? Sociology, 46(2), 354–364. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038511419195

- Australia Council. 2020. Creativity Connects Us: Corporate Plan 2019-2023, https://www.australiacouncil.gov.au/about/strategic-plan-and-corporate-plan/

- Bourdieu, P. (1979). Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste. Le Editions de Minuit. English translation, 1984. Abindgon, Oxford: Routledge Kegan & Paul.

- Brubaker, R., Loveman, M., & Stamatov, P. (2004). Ethnicity as cognition. Theory and Society, 33(1), 31–64. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:RYSO.0000021405.18890.63

- Burchell, D. (2006, January 27). Both sides of the political divide stoop to playing the race card. The Australian.

- Burton, J., Nandi, A., & Platt, L. (2010). Measuring ethnicity: Challenges and opportunities for survey research. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 33(8), 1332–1349. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870903527801

- Callier, L., & Hanquinet, L. (with Jean-Louis Genard and Dirk Jacos) (2012). Étude Approfondie Des Pratiques et Consommation Culturelles de La Population En Fédération Wallonie- Bruxelles. Observatoire Des Politiques Culturelles, Etudes, no 1.

- Canada Council for the Arts. (2021). Strategic plan 2021–2026: Art, now more than ever. https://canadacouncil.ca/priorities#:~:text=2021%2D26%20Strategic%20Plan%3A,Art%2C%20now%20more%20than%20ever&text=The%20Plan%20supports%20a%20rebuild,over%20the%20next%20five%20years.

- Chu, E. W., Fiona, A., & Verrelli, S. (2017). Biculturalism amongst ethnic minorities: Its impact for individuals and intergroup relations. Australian Journal of Psychology, 69(4), 229–236. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajpy.12153

- Connelly, R., Gayle, V., & Lambert, P. S. (2016). Ethnicity and ethnic group measures in social survey research. Methodological Innovations, 9, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1177/2059799116642885.

- Conner, L. (2022). Disrupting the audience as monolith. In M. Reason, L. Conner, K. Johanson, & B. Walmsley (Eds.), Routledge Companion to Audiences and the Performing Arts (pp. 53–67). Routledge.

- Creative New Zealand. (2015). Six projects funded to increase diversity in Auckland’s arts ‘[Blog post]’. http://www.creativenz.govt.nz/news/six-projects-funded-to-increase-diversity-in-auckland-s-arts

- Danforth, L. M. (2001). Is the “world game” an “ethnic game” or an “aussie game"? narrating the nation in Australian soccer. American Ethnologist, 28(2), 363–387. https://doi.org/10.1525/ae.2001.28.2.363

- Deaux, K. (2018). Racial/ethnic identity: Fuzzy categories and shifting positions. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 677(1), 39–47. https://doi.org/10.1177/000271621875483.

- Department for Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS). (2016). The Culture White Paper, www.gov.uk/government/publications

- Fairley, G. (2016). Beyond the racist hyphen.: Artshub, available at https://www.artshub.com.au/news/features/beyond-the-racist-hyphen-252658-2354441/

- Freshwater, H. (2009). Theatre and audience. Macmillan Education.

- Gans, H. J. (1979). Symbolic ethnicity: The future of ethnic groups and cultures in America*. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 2(1), 1–20. http://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.1979.9993248

- Gebrekidan, B. (2018). African-Australian’ identity in the making: Analysing its imagery and explanatory power in view of young Africans in Australia. Australasian Review of African Studies, 39(1), 110–112. https://doi.org/10.22160/22035184/ARAS-2018-39-1/110-129

- Gill, R. (2016). Will Asia TOPA be the ‘game changer’ Australian arts companies have been wishing for? Daily Review, 26 September, https://dailyreview.com.au/asia-topa-reveals-program/

- Kymlicka, W. (1996). Social unity in a liberal state. Social Philosophy and Policy, 13(1), 105–136.

- Matthews, J. (2002). Racialised schooing, ‘ethnic success’ and Asian-Australian students. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 23(2), 193–207. https://doi.org/10.1080/01425690220137710

- Meghji, A. (2019). Encoding and decoding black and white cultural capitals: Black middle-class experiences. Cultural Sociology, 3(1), 3–19. https://doi.org/10.1177/1749975517741999

- Merino, M.-E., & Tileagă, C. (2011). The construction of ethnic minority identity: A discursive psychological approach to ethnic self-definition in action. Discourse & Society, 22(1), 86–101. https://doi.org/10.1177/0957926510382834

- Noble, G., & Ang, I. (2018). Ethnicity and cultural consumption in Australia. Continuum, 32(3), 296–307. https://doi.org/10.1080/10304312.2018.1453464

- Odom, G., & Raghunathan, G. (2022). Which global? Which local?: Aucitya, Rasa, development, Àṣẹ and other demands on the audience. In M. Reason, L. Conner, K. Johanson, & B. Walmsley (Eds.), Routledge companion to audiences and the performing arts (pp. 96–110). Routledge.

- Oman, S. (2019). Leisure pursuits: Uncovering the ‘selective tradition’ in culture and well-being evidence for policy. Leisure Studies, 39(1), 11–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/02614367.2019.1607536.

- Pham, T., Berecki-Gisolf, J., Clapperton, A., O'Brien, K. S., Liu, S., & Gibson, K. (2021). Definitions of culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD): A literature review of epidemiological research in Australia. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(2), 737. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18020737

- Porter, M., Todd, A., & Zhang, L. (2016). Ethnicity or cultural group identity of pregnant women in Sydney, Australia: Is country of birth a reliable proxy measure? Women and Birth, 29(2), 168–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wombi.2015.10.001

- Prewitt, K. (2018). The census race classification: Is it doing its job? The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 677(1), 8–24. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716218756629

- Schaap, J., & Berkers, P. (2020). You’re Not supposed to be into rock music’: Authenticity maneuvering in a white configuration. Sociology of Race and Ethnicity Online, 6(3), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1177/233264921989967.

- Sedgman, K. (2018). The Reasonable Audience: Theatre Etiquette, Behaviour Policing, and the Live Performance Experience. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Vertovec, S. (2007). Super-diversity and its implications. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 30(6), 1024–1054. http://doi.org/10.1080/01419870701599465

- Walmsley, B. (2016). Deep hanging out in the arts: an anthropological approach to capturing cultural value. International Journal of Cultural Policy, 24(2), 272–291. http://doi.org/10.1080/10286632.2016.1153081

- Wetherell, M. (2009). Theorizing Identities and Social Action. Sage.

- Williams, M., & Husk, K. (2013). Can we, should we, measure ethnicity? International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 16(4), 285–300. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2012.682794