ABSTRACT

The impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic in the creative and cultural industries have been closely tracked by researchers, professional bodies, and arts organisations. In the period of recovery that has followed, emphasis has moved towards building a more inclusive and sustainable industry. Yet beyond the headline statistics, accounts of the support needs of creative workers – as identified in their own words – are less forthcoming. This paper reports on open responses collected during April-May 2021 as the United Kingdom began to lift lockdown restrictions. Thematic analysis of responses identified three overarching themes identified by respondents as central to sustainable recovery: (i) Financial Infrastructures; (ii) Artistic communities; and (iii) Future-proofed professional landscapes. The findings support previous research that has emphasised the need for recovery to prioritise supporting individual artists and the importance of freelance voices at all stages of policy and decision making to ensure equitable development for the future.

Introduction

The immediate impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic were felt keenly in the creative and cultural industries. The closures of theatres, galleries, and nightclubs halted income streams across the creative sector. In an industry dominated by short-term project work and freelancers, revenue across the cultural industries in the United Kingdom (UK) almost halved (DCMS, Citation2020; Oxford Economics, Citation2020), with many seeing livelihoods disappear overnight (Spiro et al., Citation2021). The government packages of support that came in response, notably the £1.57 billion Cultural Recovery Funds (CRF) and the Self Employment Income Support (SEISS), were initially praised for their rapid roll-out and responsiveness, providing a lifeline for many struggling institutions and creative workers. However, gaps in both schemes were seen to highlight a poor understanding of the diverse ecologies of the cultural sector (Comunian & England, Citation2020; Sargent et al., Citation2021). Millions of creative workers did not meet the eligibility criteria for the SEISSFootnote1, and the flagship CRF missed many organisations that were most vulnerable, with the majority of the funds going to institutions that had a history of Arts Council funding and public investment (Walmsley et al., Citation2022).

Performing arts were the major beneficiaries, with 30% of the CRF funds directed towards performing arts organisations (Siepel et al., Citation2021). Yet, the individual artists within those institutions often saw little trickle down of those funds. Although individuals were directed towards the SEISS, the design of the support packages was inappropriate for the reality of most creative income streams, with reports that at least one third of musicians (Musicians’ Union, Citation2021) and three quarters of visual artists (ACME, Citation2021) were unable to apply. In addition, those with mixed freelance-portfolio working patterns (which describes the majority of visual artists, illustrators, and film-makers) faced both reductions in work from shuttered businesses alongside restrictions on their own creative practice through the lack of access to studio space, difficulties obtaining materials (ACME, Citation2021), and lost rehearsal opportunities and collaboration (Sargent et al., Citation2021).

The intermittent closures of the nearly two years that followed left the cultural industries fragmented, with the experiences of creative professionals increasingly polarised by industry, employment type, income stream, and career stage. Towards the latter stages of 2021, sectors including film, TV, radio, photography, and publishing showed increasing levels of activity, whilst those more reliant on audiences’ close contact, including music, theatre, and performing arts, were still decimated (Siepel et al., Citation2021; Walmsley et al., Citation2022). Other disparities have also been evident, with industries that have strong and well-organised representation (such as that provided by the Musicians’ Union and Equity for those in the performing arts), quicker to adapt and put in place COVID-safe workplace guidance and cancellation protections, in contrast to creatives in more fragmented sectors, such as painters, who have been less represented in policy discussions (Jones, Citation2022). The ongoing economic shocks that have followed the pandemic, including the cost-of-living crisis, placed further pressure on those with portfolio careers, who carry high levels of personal and professional economic risk (Jones, Citation2022). Research undertaken during this period has shown how the “immunity” of the creative workforce is beginning to wane, with disabled, younger, and minority professionals appearing to leave creative work at a higher rate than ever before (Walmsley et al., Citation2022).

Portfolio working, creative precarity, and wellbeing

Pre-pandemic, the instability of creative work was already well-documented (Cohen, Citation2015; Gill & Pratt, Citation2008; Morgan & Nelligan, Citation2018), with the nature of ad hoc, long, and low paid hours contributing to burnout and mental health concerns across arts industries (Dobson, Citation2010; Vaag et al., Citation2016; Wilkes et al., Citation2020). Fatigue and over-rehearsal are the leading causes of injury for professional dancers (Kozai et al., Citation2020) and contributors to the high levels of musculoskeletal pain seen in orchestral musicians (Kenny & Ackermann, Citation2015). Financially, many professionals cannot make a living from their artistic practice alone. As Thompson (Citation2008) notes, the majority of the roughly 5,000 artists who have some representation in mainstream galleries will still supplement their income through teaching, writing, or supportive partners (Thompson, Citation2008, p. 64). Overall, visual artists have an average annual income of £16,150, with less than half of this coming from their art (TBR, Citation2018). Similarly, median earnings for those working in literature have dropped from £12,330 in 2007 to £7,000 (Thomas et al., Citation2022) meaning alternative work is essential for most. Portfolio patterns of performing, teaching, and other related activities such as arts administration, research, and community work are also common in the performing arts, where the pressure to make ends meet can create other professional risks.

While precarity is often regarded as a condition of artistic labour and creative freedom, work that is governed by instability can inflict high emotional and social burdens, and entrench inequalities across the sector (Comunian & England, Citation2020; Morgan & Nelligan, Citation2018). This type of work can also fuel a “temporal precarity”, where artistic practices are dominated by “the frenetic demands of a speeded-up, unstable, and fragmented social world” (Serafini & Banks, Citation2020, p. 1). At the outset of the pandemic, experts voiced concerns that instability and exploitative working patterns were likely to worsen as a result of poor support offered to the industry (Banks, Citation2020; Comunian & England, Citation2020; Eikhof, Citation2020). Two years after the intial lockdown, the mental and social wellbeing of the workforce remains a concern, with high levels of anxiety, depression, and loneliness persisting despite restrictions easing (Spiro & Shaughnessy et al., Citationunder review).

The wellbeing of workers in the creative industries is closely linked to their work; creative professionals experience a strong sense of emotional identity and satisfaction from their practice (Ascenso et al., Citation2017; Dobson, Citation2010; Oakland et al., Citation2012). However, the erosion of the perceived value of creative work – evident in austerity-era policymaking and in part echoed by the perceived inadequate supports provided during the pandemic – has led to a workforce that feels undervalued and abandoned (Cohen & Ginsborg, Citation2021, Citation2022; Comunian & England, Citation2020; Flore et al., Citation2021; Shaughnessy et al., Citation2022). As time passes and the challenges to the sector persist, it is becoming increasingly difficult to unpick the immediate effects of the pandemic from pre-existing structural inequalities. As Strong and Cannizzo (Citation2020) noted, instability was not new, with the pandemic acted as a “a worst-case scenario where the full effects of this precarity were suddenly brought home to workers en masse” (Strong & Cannizzo, Citation2020, p. 9; Flore et al., Citation2021). Factors that were initially disguised, such as Brexit, are also now beginning to manifest (Walmsley et al., Citation2022).

Positive changes have nevertheless emerged during the pandemic, including increased accessibility of arts engagement through hybrid performance (Sargent et al., Citation2021; Vincent, Citation2022), increased visibility of the precarity of creative work (Comunian & England, Citation2020), and opportunities for artistic reflection (Shaughnessy et al., Citation2022; Spiro et al., Citation2021; Warran et al., Citation2022). To preserve these positive changes and address the structural problems within the industry, experts have called for recovery from the pandemic to be met with reformed funding models and working protections (Banks & O’Connor, Citation2021). Particular attention has been drawn to the financial infrastructures which limit accessibility and inclusion of both entry into, and retention of, diversity within the sector (Walmsley et al., Citation2022; Wreyford et al., Citation2021).

Many of the policies and statistics thus far described have been drawn from industry bodies. The Department for Culture Media and Sport (DCMS), Treasury, and Arts Council England (ACE) responses to the pandemic have been criticised as relying too heavily on information gathered from their national portfolio organisations when designing pandemic supports, and failing to listen to creative freelancers and take account of grassroots, community creative ecologies (Jones, Citation2022). Listening to individual artists’ voices and understanding individual perspectives can help inform appropriate support for careers, tailor such support to individual sub-sectors, and highlight common experiences across the creative industries that could allow for widespread impact of new policies (Comunian & England, Citation2020; Wilson et al., Citation2020). Responding to the calls to “build back better” within the creative industries (Banks & O’Connor, Citation2021; Reason, Citation2022), there is a need to understand the experiences of the individuals who work in local creative ecologies, which can help to improve the ways in which cultural organisations engage individual artists and become more mindful of how their practices impact upon the wellbeing of individual arts professionals. This study therefore sought to understand what supports arts professionals feel are needed, through a single research question: What are the challenges and support needs, as identified by individual artists themselves, for sustainable and progressive development in the creative industries?

Methods

This study took a large-scale qualitative approach to address the research question and understand artists’ perceived challenges and support needs in their own words. Data were collected as part of the HEartS Professional survey (Spiro et al., Citation2021), in which workers in the arts and cultural sectors were asked about the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on their health, wellbeing, and livelihoods. The multi-wave survey was conducted between 2020 and 2022 and targeted all those working in artistic professions, meaning respondents were both freelancers and those working in arts organisations. This paper reports on qualitative data collected in the second wave of the survey (April – May 2021; for results and discussion of the quantitative results see Spiro & Shaughnessy et al., Citationunder review, and for the first survey see Spiro et al., Citation2021). The survey included new open questions, validated scales on social and mental wellbeing and questions on annual income, working patterns, and effects of the pandemic on professional and personal activities. The current article reports on the two open questions within the survey: (1) What support do you feel would be most useful over the next 12 months? (Feel free to refer to any type of support, for any matter); and (2) In your opinion, what do you think are the most significant problems in the arts sector that research needs to address?

Respondents

Responses (N = 685) were collected through the online survey platform Prolific and via an email database of previous survey respondents from 20th April to 24th May 2021. The survey was open to professionals working in the arts in any capacity who live in the UK. All respondents answered the survey in a personal capacity, rather than on behalf of their organisation. Most respondents were aged between 26–55 (70%, mean age = 38). Respondents represented a range of UK areas across the UK, with a large proportion living in London or the Southeast (47%), 7% from Scotland, and 11% from the Midlands. Over two-thirds of respondents identified as female (64%), 80% were white, and 58% had at least a tertiary degree ( details demographic details in full).

Table 1. Sociodemographic, professional and economic characteristics of the sample, HEartS Professional Survey, N = 685.

Many of the respondents reported several professional activities across multiple different areas (n = 177). Roughly a third reported working in music and sounds arts (n = 199, 29%) (with classical music, n = 122, and pop, n = 84, being highly represented), a third also worked in performing arts (n = 218, 32%), nearly half in visual art (49%) (with film/video making/photography highly represented, n = 174) and 11% working in literature. Respondents also reported a mixture of employed and freelance work, with 53% earning the majority of their income through freelance work and 74% having at least some freelancing as part of their work portfolio. These proportions differed across different sub-sectors, with those in visual art reporting an average of 54% of their income through freelance working, 60% in performing arts, 63% in music and sound arts, and 56% in literature. It was also evident that across the different sub-sectors, experiences of financial hardship were different. Our survey found that 71% of respondents working in the performing arts had experienced financial hardship as a result of the pandemic, compared with only 41% of those in literature. details a full breakdown of professional specialisms, freelance working, and financial hardship. While our sample does not exhaustively cover all areas of creative work, it aligns in many areas to the 2018–2019 Arts Council report on equality and diversity in the institutions they support (Arts Council England, Citation2018). Indicative quotations presented in the results below have been provided along with the respondents’ identified gender and their age.

Table 2. Breakdown of professional specialisms, freelance and financial hardship of the sample, HEartS Professional Survey, N = 685.

Analysis

685 respondents responded to two open questions (with some leaving blank answers). Across the two open questions, 999 responses were collected (once missing and nonsense answers were removed) and analysed following a reflexive thematic approach that took a six-stage inductive process (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006, Citation2022). This included familiarisation with the data (Phase 1) then generating initial codes in a bottom-up manner for each free text response (Phase 2). These codes were subsequently sense checked and collated into initial themes (Phase 3). These initial themes were then discussed with members of the research team, and the resulting 11 sub-themes were then grouped into three overarching main themes (Phase 4). The finalised themes were then defined, with a thematic map produced (Phases 5 and 6) in discussion within the research team.

Results and discussion

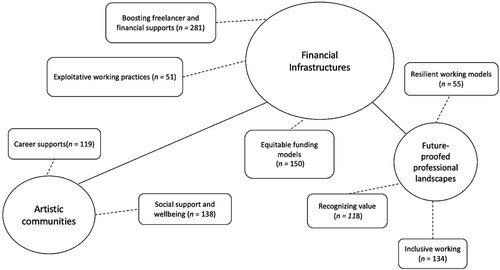

Analysis found three overarching themes that reflect respondents’ views on where supports and change were needed most: (1) Financial infrastructures, (2) Artistic communities, and (3) Future-proofed professional landscapes. Within these themes, there were nine sub-themes of more specific areas of support which are visualised in .

Financial infrastructures (Theme 1)

The precarity of working conditions that are characteristic of arts (and particularly freelance) work and the supports needed to navigate that precarity (Boosting freelancer and financial supports, sub-theme 1.1, n = 199) represented the primary concerns reported by the respondents. This included understanding complex funding structures, the instability of short-term contracts, low-pay, long working hours, and lack of employment protections, all of which were perceived to have been accentuated during the pandemic. The minimal infrastructures around creative work including no sick pay, parental leave, and cancellation protections left them vulnerable to the shocks of a lockdown as well as feeling neglected by the supports that were available.

How can a billion-pound industry can just be left to perish when other sectors have been given help when they do not create as much revenue? [Actor, 56, Female]

Financial support is sorely needed. So few people I know (myself included) within my area of the creative arts were able to claim the financial support offered by the government. It didn’t go far enough, and I feel proper financial support is seriously needed to support people in the creative industries. [Visual artist, 28, Female]

As the rhetoric of “recovery” from the pandemic began to dissipate, performers noticed a return to poorer working practices and pay:

We are now being asked to work for smaller fees – another example of the individual having to bear the brunt of the funding crisis. Having been extremely adversely affected during the lockdowns (with not much happening between times) musicians are expected to go back to work under worse conditions than last year. [Classical musician, 56, Male]

I think we all need to be fairly compensated for our work once more. Bookers are now getting most of us to perform for nothing either in person or online and that is professionally wrong on every level. [Cabaret artist and storyteller, Female, 89]

[There is a] lack of stable funding – planning has always been difficult if sponsorship is not forthcoming. The bulk of Government emergency funding tends to go to institutions rather than freelancers – it rarely finds its way to individuals. [Musician, 56, Male]

[There is a] historic imbalance between large scale spending on big capital building projects (new museums, galleries, concert halls etc), arts management and the funding of creative professionals, especially at grass roots level. [Visual artist, 57, Female]

Despite this, there were some positives that emerged from the pandemic supports. The relative creative freedom and financial stability that the SEISS provided for the limited few has opened the door to wider discussions on how universal incomes may be used to support and protect artists.

I think the kind of basic income that performers have access to in some other countries would be a way of levelling the playing field in terms of privilege in my profession. The SEISS grants, while I know deeply flawed in the way they were distributed, were a taste of that. [Actor, 57, Female]

Reorganization of the economy and society at a systemic level. Investing in arts specifically can only stem damage but pulling people out of poverty and economic uncertainty creates artists with choices and freedom. [Music and physical theatre artist, 30, Male]

The impacts of the pandemic were also seen to exacerbate long-term problems. This included becoming further reliant on poor and exploitative working practices as budgets and productions became further constrained. Intertwined with financial supports was a need for measures that establish artistic protections, and the development of policies to prevent exploitation (Exploitative working practices, sub-theme 1.3):

[We need] better working conditions for freelancers in the arts. The arts sector is inconsistent in its ability to support freelancers and is at increasing risk of facing litigation processes as a result of its poor employment practices (examples include low pay rates, short-term termination of contracts without due compensation, and insufficient efforts to recruit representatively). [Singer, 25, Female]

[The problem is] how easily exploited artists are, particularly young artists who don’t know how to value their work cost-wise or assert their boundaries with customers/clients. [Artist/writer, 21, Female]

I think for musicians the most significant problem they face is the lack of income they make from their actual music. Sales of music are so low the majority of music listening is now streaming, and the amount of money made from streaming is miniscule. They rely on touring for most of their income and COVID has really highlighted this problem. Also, the royalty splits for songwriters are terrible through streaming which has left a lot of them with little to no income. [Musician, 35, Female]

Over the last twenty years or so, with the internet and then social media, art is thought of by most people as being commercially free to find and use, and even to commission. Work is either stolen (unwittingly, or otherwise) and used without permission, or when permission is requested they expect it to be given for free. [Film-maker, 24, Female]

Artistic communities (Theme 2)

Within the two sub-themes for Theme 2, respondents emphasised the importance of communities and how their decline over the course of the pandemic impacted both their career progression (sub-theme 2.1: Career supports, n = 119) as well as their own personal wellbeing (sub-theme 2.2: Social support and wellbeing, n = 138). For many, these impacts were intertwined, both serving as important factors to freelance success in the creative industries (Komorowski et al., Citation2021; Pratt, Citation2021). However, respondents distinguished between the loss of a sense of community upon their career progression and the separate, often competing consequences of the changing working relationships and competition on their wider mental health.

Among some professional communities, during the initial lockdowns there was a sense of solidarity among artists (Flore et al., Citation2021). This diminished towards the later stages of the pandemic and there was growing awareness (and some resentment) of the divergence in experiences of creative professionals, such as between those who were eligible for support (either through furlough or SEISS) or were able to continue working (Walmsley et al., Citation2022). As work moved online and became increasingly remote, the informal outlets for expressions of resentment and grief were lost:

Being self-employed can be very lonely at times and the pandemic has made it near-impossible to get by. I would appreciate some connections with people, in person. Like-minded creatives coming together like we did before sharing our struggles having some creative outlet. I want to build something with people. [Film maker/photographer, 30, Male]

I feel like coaching would be extremely helpful. The pandemic put a stopper in my career progression and now as we re-enter the world, I’m not sure of which direction to go in or how best to get on the right path for growth in my work. [Textiles artist, 25, Female]

I think it’s fair to say there are several generations of younger people … at the beginnings of their careers like me who have been seriously affected in terms of opportunity, moral, mental health and financial situation after 14 months of this … I know many of my peers feel all we can do is just get by, cannot see progression. [Music artist/dancer, 26, Female]

For people who work in the arts it’s their mental health, it’s been tough, and organisations aren’t doing enough for their staff / wider arts community. [Folk/pop musician, 56, Female]

Future-proofed professional landscapes (Theme 3)

As emphasised by reports and our own data, the last two years have served to amplify the existing financial inequalities of the creative industries. Infrastructures that perpetuated low pay and unstable work have worsened the impacts, particularly for those groups with less financial resilience (see Theme 1). The ongoing uncertainty of additional restrictions, economic disruption, and public health crises had shaken the confidence of creative artists across many industries, laying bare the precarity of their work (Strong & Cannizzo, Citation2020). In the face of this materialised uncertainty, respondents increasingly looked to the future and considered opportunities and requirements for change.

For many the systemic problems of “Ableism. Racism. Sexism”, were at the forefront of their priorities for recovery (Sub-theme 3.1, Inclusive working, n = 134). Beyond the headline terms of “diversity”, “racial inequality”, “class”, “inclusivity”, and “accessibility”, some respondents elaborated on concerns, now evidenced in research, that barriers to inclusive practices and equality of opportunity within the cultural industries are more complex than loss of income. It was noted that the pandemic has likely accentuated inequalities identified above, particularly for women, people who experience racism, and disabled individuals (Eikhof, Citation2020; Walmsley et al., Citation2022).

Existing barriers to entry roles for people from different socio-economic backgrounds, and support should be implemented to employ more diverse workforces in terms of providing opportunities for BAME candidates and those with disabilities or neurodivergency across as many access points as possible. [Visual Artist, 29, Female]

This pandemic has highlighted the fragility of the performing arts sectors … all companies in the performing arts sector need to research how they can financially prepare for another crisis, and what measures they can put in place to allow performances to continue in a way that is safe for not only staff but the paying public. [Actor and dancer, 27, Male]

Despite the UK Arts sector being a huge contributor to the economy, it’s regarded by government as an “add-on”, a nice extra. [Folk/country musician, 59, Female]

[We need to] change the perception that art is an extra that can be eliminated when money is tight, working to give artists more credibility and are often quite ordinary people who work really hard generally for very little. [Sculpture/textiles, 62, Female]

The links between arts, wellbeing, and productivity are crucial to understand as society reshapes itself with budgetary constraints post pandemic. I expect the government to argue (as it sometimes has, effectively) that arts are a luxury we can’t afford in schools, but what evidence shows that arts and training in creativity and artistic expression are a high priority for school-aged children and society in general? [Music artist/writer, 48, Male]

There are so many opportunities to learn from the lockdown experience and how arts impacts on social wellbeing … In returning to working life we need to embrace the value of arts and culture has been the driving force behind so many people finding solace, understanding, and lifting spirits during lockdown whether that's music, visual arts, theatre, film, dance, or crafts. [Music charity worker, 48, Female]

General discussion

The COVID-19 pandemic has exposed the vulnerabilities of work in the cultural sector. Respondents to our survey highlighted the perceived support needs of a creative workforce that report being overworked and underpaid. As researchers, industry bodies, and artists themselves have emphasised, many of these factors pre-date the disruptions of the pandemic. These results confirm the findings of wider research in this area, particularly our work exploring the experiences of early career professionals during the pandemic (Shaughnessy et al., Citation2022), as well as large scale reports from the Centre for Cultural Value (Walmsley et al., Citation2022), and Policy and Evidence Centre (PEC) (Siepel et al., Citation2021) that have highlighted the profound and uneven impacts of the pandemic across different sub-sectors. While the disruptions of the last three years have been extremely challenging, there is an opportunity (which is keenly felt by artists themselves) to reshape the working practices of the cultural industries and create a more sustainable and equitable workforce. While not comprehensive, the pandemic policies provided a small insight into an alternative model for the funding of the arts, and emphasise the need for cultural organisations to better support those freelance individuals that make up such a core part of their workforce. If, as the pandemic may have shown, there is greater public consciousness of the “good work” of the arts, then policy should reflect this and tackle the flexploitation that have become symptomatic of the cultural industries. The lack of safeguards for individuals and grassroots organisations further emphasises the legacy failures of policy to encourage “resilience” within the sector (Comunian & England, Citation2020) and highlights the divisions between the institutions and those “flexible or freelance workers who bear the costs and risks of uncertainty” (Pratt, Citation2017, p. 136). As PEC (Siepel et al., Citation2021) found, the pandemic has led to an increase for many businesses in the number of freelancers with whom they work. Ensuring that leaders and decision makers are educated in how to engage freelancers responsibly and ethically is essential to promoting equitable working environments in the future.

It is notable from the results above that artists are still struggling to access support. However, the responses highlight how freelancers and workers themselves have clear understanding of what their support needs are, and the changes required in their industries. Supporting those across under-represented subsectors to strengthen their voices and be heard at the highest level of policymaking will enable supports to be designed that are appropriate to the needs of individuals. This includes rebalancing funding to invest directly in creatives and local arts infrastructures (Genders, Citation2021). Emphasis on supports that reach individuals directly, such as initiatives in France, Ireland, and New York that have provided models for basic income schemes, provide an example of future possibilities here. Others, such as reformulating structures to give local authorities and regional structures further control could further address inequities in this area. However, as the most recent announcements of the ACE 2023–2026 National Portfolio Organisation (NPO) awards have suggested, moving funding from one area at the expense of another is likely to be less effective than empowering regions with control over their own funding decisions, thereby activating local embedded knowledge of the specific needs of each community.

Conclusion

The financial stability, mental wellbeing, and diversity of those working in the creative sectors are in clear need of support. This reinforces the concerns raised at the outset of the pandemic, notably that there would be long term damage that went beyond immediate financial outlays and lockdown disruptions (Banks & O’Connor, Citation2021; Comunian & England, Citation2020; Eikhof, Citation2020). It is striking how closely the support needs raised in these responses overlap with the themes highlighted elsewhere by early-career professionals (Shaughnessy et al., Citation2022), despite the broader age sample and diversity in disciplines. Similarly, the degree to which the provided supports were seen to miss the mark highlights the importance of this work and of understanding individual perspectives.

While this study reinforces wider research in this area, it has certain limitations. First, the data was collected at a specific point in time when pandemic restrictions were beginning to be eased. As pandemic impacts are now becoming intertwined with factors including Brexit and the cost-of-living crisis, the needs of arts professionals are likely to continue to develop and change. In addition, although the scope of disciplines represented by the respondents was broad, it is still limited in its representation of some artistic and demographic groups. In particular, nearly half of the respondents reported being from London or the Southeast. Future research should continue to trace the wellbeing of arts professionals across differing geographic locations.

In light of these findings, we echo our previous recommendations (Shaughnessy et al., Citation2022, p. 8) to respond to the needs of creative professionals:

– Remove financial precarity through long term funding models that directly support the individual worker. Providing this financial stability will further help to promote diversity in the sector and allow artists to take more creative risks and build their businesses with less financial jeopardy.

– Strengthen creative networks for freelancers, including mentoring and guidance about how to build a portfolio, charge fair prices, and protect mental and physical health.

– Strengthen the representation of freelancers and grassroots organisations within information collection and decision-making processes, elevating those voices to the heart of government policy such as in the Cultural Renewal Taskforce (alongside key stakeholders). As others have noted, there is a need for “regenerative” practices across the industry (Walmsley et al., Citation2022). This will help institutions such as the DCMS and ACE to target and commission services and funding, as well as ensure that those with lived experience of community based, socially engaged practice help to drive future policy development. As Banks (Citation2022) notes, there is now a key need for “new creative economy imaginaries” that can bring about an impactful and inclusive creative industry for all involved.

Overall, these findings identify clear steps that can be taken to support sustainable and progressive development in the creative industries to respond to artists’ needs: provide stable and fair pay and working conditions, build accessible professional networks and infrastructures that can provide personalised support mental and physical wellbeing, and embed diverse and inclusive practices at all stages of artistic work. This will promote and protect the wellbeing of creative workers alongside, not at the expense of, the financial viability of the sector.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to all the arts professionals who took part and shared their experiences in our survey.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Eligibility for the Self-Employment Income Support Scheme varied slightly across each of the five rounds, but included being self-employed and required individuals to have traded in tax years, 2019–2020 and 2020 to 2021. More details can be found here: https://www.gov.uk/guidance/claim-a-grant-through-the-coronavirus-covid-19-self-employment-income-support-scheme.

References

- ACME. (2021). Studio practice fund part two: Discussion August 2021. https://acme.org.uk/assets/Studio-Practice-Fund-part-2-Discussion-updated-doc.pdf

- Ascenso, S., Williamon, A., & Perkins, R. (2017). Understanding the wellbeing of professional musicians through the lens of positive psychology. Psychology of Music, 45(1), 65–81. https://doi.org/10.1177/0305735616646864

- Banks, M. (2020). The work of culture and C-19. European Journal of Cultural Studies, 23(4), 648–654. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367549420924687

- Banks, M. (2022). Re-futuring creative economies: Beyond bad dreams and the banal imagination. In R. Comunian, A. Faggian, J. Heinonen, & N. Wilson (Eds.), A Modern Guide to Creative Economies (pp. 216–227). Cheltenham.

- Banks, M., & Hesmondhalgh, D. (2009). Looking for work in creative industries policy. International Journal of Cultural Policy, 15(4), 415–430. https://doi.org/10.1080/10286630902923323

- Banks, M., & O’Connor, J. (2021). “A plague upon your howling”: art and culture in the viral emergency. Cultural Trends, 30(1), 3–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/09548963.2020.1827931

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2022). Thematic Analysis: A Practical Guide. SAGE.

- Camlin, D. A., & Lisboa, T. (2021). The digital ‘turn’ in music education. Music Education Research, 23(2), 129–138.

- Cohen, N. S. (2015). Cultural work as a site of struggle: Freelancers and exploitation. In C. Fuchs & V. Mosco (Eds.), Marx and the political economy of the media (pp. 36–64). Brill. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004291416_004

- Cohen, S., & Ginsborg, J. (2021). The experiences of mid-career and seasoned orchestral musicians in the UK during the first COVID-19 lockdown. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 645967. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.645967

- Cohen, S., & Ginsborg, J. (2022). One year on: The impact of COVID-19 on the lives of freelance orchestral musicians in the United Kingdom. Frontiers in Psychology, 13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.885606

- Comunian, R. (2011). Rethinking the creative city: The role of complexity, networks and interactions in the urban creative economy. Urban Studies, 48(6), 1157–1179. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098010370626

- Comunian, R., & Conor, B. (2017). Making cultural work visible in cultural policy. In V. Durrer, T. Miller, & D. O’Brien (Eds.), The Routledge Handbook of Global Cultural Policy (pp. 265–280). Routledge.

- Comunian, R., & England, L. (2020). Creative and cultural work without filters: COVID-19 and exposed precarity in the creative economy. Cultural Trends, 29(2), 112–128. https://doi.org/10.1080/09548963.2020.1770577

- DCMS. (2020). Impact of COVID-19 on DCMS sectors: First report - digital, culture, media and sport committee - house of commons. In Publications and Records UK Parliament. https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm5801/cmselect/cmcumeds/291/29102.htm

- Dobson, M. C. (2010). Performing yourself? Autonomy and self-expression in the work of jazz musicians and classical string players. Music Performance Research, 3(1), 42–60.

- Eikhof, D. R. (2020). COVID-19, inclusion and workforce diversity in the cultural economy: What now, what next? Cultural Trends, 29(3), 234–250. https://doi.org/10.1080/09548963.2020.1802202

- England, A. C. (2018). Equality, Diversity and the Creative Case: A Data Report. Arts Council England.

- Flore, J., Hendry, N. A., & Gaylor, A. (2021). Creative arts workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: Social imaginaries in lockdown. Journal of Sociology, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1177/14407833211036757

- Genders, A. (2021). Precarious work and creative placemaking: Freelance labour in Bristol. Cultural Trends, 31(5), 433–447. https://doi.org/10.1080/09548963.2021.2009735

- Gill, R., & Pratt, A. (2008). In the social factory?: Immaterial labour, precariousness and cultural work. Theory, Culture & Society, 25(8), 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263276408097794

- Hesmondhalgh, D., & Baker, S. (2010). ‘A very complicated version of freedom’: Conditions and experiences of creative labour in three cultural industries. Poetics, 38(1), 4–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.poetic.2009.10.001

- Hume, V., & Parikh, M. (2022). From surviving to thriving: Building a model for sustainable practice in creativity and mental health. Culture, Health and Wellbeing Alliance, 1–26.

- Jeannotte, M. S. (2021). When the gigs are gone: Valuing arts, culture and media in the COVID-19 pandemic. Social Sciences and Humanities Open, 3(1), 100097.

- Jones, S. (2022). Cracking up: The pandemic effect on visual artists’ livelihoods. Cultural Trends, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/09548963.2022.2120382

- Kenny, D., & Ackermann, B. (2015). Performance-related musculoskeletal pain, depression and music performance anxiety in professional orchestral musicians: A population study. Psychology of Music, 43(1), 43–60. https://doi.org/10.1177/0305735613493953

- Komorowski, M., Lupu, R., Pepper, S., & Lewis, J. (2021). Joining the dots—understanding the value generation of creative networks for sustainability in local creative ecosystems. Sustainability, 13(22), 12352. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132212352

- Kozai, A. C., Twitchett, E., Morgan, S., & Wyon, M. A. (2020). Workload intensity and rest periods in professional ballet: Connotations for injury. International Journal of Sports Medicine, 41(6), 373–379. https://doi.org/10.1055/a-1083-6539

- Morgan, G., & Nelligan, P. (2018). Creativity Hoax: Precarious Work and the gig Economy. Anthem Press.

- Musgrave, G. (2023). Music and wellbeing vs. Musicians’ wellbeing: Examining the paradox of music-making positively impacting wellbeing, but musicians suffering from poor mental health. Cultural Trends, 32(3), 280–295. https://doi.org/10.1080/09548963.2022.2058354

- Musicians’ Union. (2021). Coronavirus presses mute button on music industry. Retrieved 20 October, 2021, from https://musiciansunion.org.uk/news/coronavirus-presses-mute-button-on-music-industry

- Oakland, J., MacDonald, R. A., & Flowers, P. (2012). Re-defining ‘Me’: Exploring career transition and the experience of loss in the context of redundancy for professional opera choristers. Musicae Scientiae, 16(2), 135–147. https://doi.org/10.1177/1029864911435729

- Oxford Economics. (2020). The projected economic impact of COVID-19 on the UK creative industries. Retrieved November 12, 2021, from https://www.oxfordeconomics.com/resource/the-projected-economic-impact-of-covid-19-on-the-uk-creative-industries/

- Petrides, L., & Fernandes, A. (2020). The successful visual artist: The building blocks of artistic careers model. The Journal of Arts Management, Law, and Society, 50(6), 305–318. https://doi.org/10.1080/10632921.2020.1845892

- Pratt, A. C. (2017). Beyond resilience: Learning from the cultural economy. European Planning Studies, 25(1), 127–139. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2016.1272549

- Pratt, A C. (2021). Creative hubs: A critical evaluation. City, Culture and Society, 24, 100384. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccs.2021.100384

- Reason, M. (2022). Inclusive online community arts: COVID and beyond COVID. Cultural Trends, 32(1), 52–69. https://doi.org/10.1080/09548963.2022.2048170

- Sargent, A. S., Levin, J., Mclaughlin, K. R., & Gelb, J. W. (2021). COVID-19 and the global cultural and creative sector-what have we learned so far? Centre for Cultural Value. Available at: https://www.culturehive.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/COVID-19-and-the-Global-Cultural-and-Creative-Sector-Anthony-Sargent.pdf

- Serafini, P., & Banks, M. (2020). Living precarious lives? Time and temporality in visual arts careers. Culture Unbound, 12(2), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.3384/cu.2000.1525.20200504a

- Shaughnessy, C., Perkins, R., Spiro, N., Waddell, G., Campbell, A., & Williamon, A. (2022). The future of the cultural workforce: Perspectives from early career arts professionals on the challenges and future of the cultural industries in the context of COVID-19. Social Sciences & Humanities Open, 6(1), 100296. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssaho.2022.100296

- Siepel, J., Velez-Ospina, J., Camerani, R., Bloom, M., Masucci, M., & Casadei, P. (2021). Creative Radar 2021: The Impact of COVID-19 on the UK’s Creative Industries. Creative Industries Policy and Evidence Centre and Sussex University. https://www.pec.ac.uk/research-reports/creative-radar-2021-the-impact-of-covid-19-on-the-uks-creative-industries

- Spiro, N., Perkins, R., Kaye, S., Tymoszuk, U., Mason-Bertrand, A., Cossette, I., Glasser, S., & Williamon, A. (2021). The effects of COVID-19 lockdown 1.0 on working patterns, income, and wellbeing Among performing arts professionals in the United Kingdom (April–June 2020). Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 594086. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.594086

- Spiro, N., Shaughnessy, C., Waddell, G., Perkins, R., Campbell, A., & Williamon, A. Modelling arts professionals’ wellbeing and career intentions within the context of COVID-19. (Manuscript under review).

- Strong, C. and F. Cannizzo (2020). Understanding Challenges to the Victorian Music Industry During COVID-19. Melbourne: RMIT University.

- TBR. (2018). Livelihoods of visual artists. Qualitative evidence report. 1-33. https://www.artscouncil.org.uk/sites/default/files/download-file/Livelihoods%20of%20Visual%20Artists%20Qualitative%20Evidence%20Report.pdf

- Thomas, A., Battisti, M., & Kretschmer, M. (2022). UK authors earnings and contracts 2022: A survey of 60,000 writers. Authors Licensing and Collecting Society. https://www.create.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/Authors-earnings-report-DEF.pdf

- Thompson, D. N. (2008). The $12 Million Stuffed Shark. Aurum Press.

- Vaag, J., Bjørngaard, J. H., & Bjerkeset, O. (2016). Symptoms of anxiety and depression among Norwegian musicians compared to the general workforce. Psychology of Music, 44(2), 234–248. https://doi.org/10.1177/0305735614564910

- Vincent, C. (2022). The impacts of digital initiatives on musicians during COVID-19: Examining the Melbourne Digital Concert Hall. Cultural Trends, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/09548963.2022.2081488

- Walmsley, B., Gilmore, A., O’Brien, D., & Torreggiani, A. (2022). Culture in Crisis: Impacts of Covid-19 on the UK cultural sector and where we go from here. Centre for Cultural Value. https://www.culturehive.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/Culture_in_Crisis.pdf

- Warran, K., May, T., Fancourt, D., & Burton, A. (2022). Understanding changes to perceived socioeconomic and psychosocial adversities during COVID-19 for UK freelance cultural workers. Cultural Trends, 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/09548963.2022.2082270

- Wilkes, M., Carey, H., & Florisson, R. (2020). The looking glass: Mental health in the UK film, television and cinema industry (Issue February). https://filmtvcharity.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/The-Looking-Glass-Final-Report-Final.pdf

- Wilson, N., Gross, J., Dent, T., Conor, B., & Comunian, R. (2020). Rethinking inclusive and sustainable growth for the creative economy: A literature review. https://disce.eu/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/DISCE-Report-D5.2.pdf

- Wreyford, N., O’Brien, D., & Dent, T. (2021). Creative majority: An all-party parliamentary group (APPG) for creative diversity report into “what works” to enhance diversity, equity and inclusion in the creative sector. http://www.kcl.ac.uk/cultural/projects/creative-majority