ABSTRACT

Before COVID-19, the cultural sector was already in crisis – suffering from precarious labour conditions, intersectional inequalities and insufficient public funding. During the pandemic, performing artists, particularly the self-employed, were hit hardest due to the difficulties of adapting their work to digital audiences, their fragile and unstable economic situation, and the limited financial support available to them. This article examines from a sociological standpoint how the pandemic has affected performing artists in London and Buenos Aires. We discuss, through online in-depth interviews and focus groups, the work strategies that 73 self-employed workers (musicians, actors, dancers, opera singers and circus artists) have deployed to cope with the crisis. Suggestions are made about how cultural policy can best support the recovery of the performing arts post-pandemic, while also reflecting on what our findings reveal about the prospects of cultural policy and the future of the performing arts in Argentina and the UK.

Introduction

As the pandemic hit, the cultural sector was already suffering a crisis of precarious labour conditions with intersectional inequalities and insufficient public funding. In Latin America, recurrent crises have meant cultural workers struggle to make a living – whether in the very informal economy, limited funding opportunities and political tumult of Chile, the authoritarianism and urban violence of Brazil, or the severe recession and accumulated public debt of Argentina. In the UK and Europe, on the other hand, public funding cuts, a living cost crisis and the increasing pressure to account for and quantify the economic value of culture, create an atmosphere of competition, commodification and a tick-boxing approach to cultural diversity.

The COVID-19 pandemic has exposed and exacerbated the deep-rooted and long-standing problems permeating cultural work on a global scale (Comunian & Lauren, Citation2020; Walmsley et al., Citation2022). Informality, precariousness, freelancing and short-term contracts are key features of work in the cultural economy (Banks et al., Citation2012; Gill & Pratt, Citation2008; Hesmondhalgh & Baker, Citation2011; Ross, Citation2008; Standing, Citation2011). Besides uncovering existing problems, the pandemic had devastating consequences for the cultural sector in light of this vulnerability and precarious working conditions, as many studies have already shown (Banks & O'Connor, Citation2021; Comunian & Lauren, Citation2020; Jones, Citation2022). The closure of museums and galleries, music venues, theatres, cultural centres, opera houses, dance halls and cafe-bars brought about a sudden interruption to the activities, relationships and movements of individuals and organisations. Yet the impact on the sector was not homogeneous and was felt differently across countries but also artforms, organisations and individuals, particularly black, disabled and low-income artists as well as those with caring responsibilities (Brooks & Patel, Citation2022).

Individual performing artists, such as actors, musicians, singers, dancers and circus artists were amongst the worst affected by the pandemic because of the precarious conditions of their work and the impossibility of performing live in venues (Spiro et al., Citation2021; UNESCO, Citation2021; Warran et al., Citation2022). This has led to the termination of contracts and the cancellations of performances, in most cases with no compensation. Although self-employment with project-based opportunities, low-pay, short-term or no contracts abound in these disciplines, how to best support freelancers during the pandemic has been unexplored (Warran et al., Citation2022).

Our research is unique in bringing together the experiences of self-employed performing artists from two very different cities, London and Buenos Aires. We seek to understand how performing artists made sense of the pandemic’s impacts during the lockdowns, what strategies they used to cope with the crisis, and how the UK and Argentina, with their different developmental contexts, can further support the recovery of the cultural sector post-pandemic. Our focus, therefore, expands studies such as UNESCO’s (Citation2021), that primarily looked at the economic impact of the pandemic on the cultural and the creative industries. Unlike many other interview-based studies, our research is based on a large qualitative sample (over 70 participants) involving in-depth interviews and focus groups, and examined a range of dimensions beyond the financial. Additionally, we have captured artists’ experiences and expectations of cultural policy support during and after the pandemic, which provides valuable evidence to inform future actions and responses.

The findings are organised around three key dimensions of the research (impacts of COVID-19, coping strategies and policy support) and are presented after, and in relation to, a discussion of theoretical debates concerning the notion of risk, cultural work and the virtualisation of everyday life. We finally reflect on conducting research across the global North and South in relation to policy support, informality, and the future of work in the performing arts. In doing so, we contribute to making visible both the disparity of experiences from different geographical contexts and that which connects freelancers across the cultural and creative sectors more globally – the need for the value of their work to be recognised in society.

Cultural work in the context of risk society, platform capitalism and digitalisation

Our research was framed within a set of theoretical debates concerning cultural work in contemporary societies, shaped by increasing risks and transformations, such as those resulting from the pandemic and digitalisation. Some of the negative consequences of technological development had been long studied by the Frankfurt School in relation to society and cultural imagination (Szpilbarg & Saferstein, Citation2016). On the one hand, the ideology of the Enlightenment and how its philosophy of progress had turned into catastrophe and tragedy with the advent of fascism. On the other, in the age of the culture industry and technological advances, consumers are subjected to the totalising power of capital, which leads to the alienation of the individual, causing an “atrophy” of imagination and spontaneity.

Similarly, the contradictions of rationality in terms of wellbeing and ecological problems were studied by Giddens (Citation1999) and Bauman (Citation2007) in post-Fordist societies. They argue that the late modern world is full of risks that were unknown to previous generations – the production of weapons, devastating wars, and now inevitable ecological catastrophes. In this context, Ulrich Beck’s notion of “risk society” (Citation1992) points to the tension between the security and uncertainty of modernisation, the ambivalence of our techno-scientific societies, where technological innovation is also a source of threats. Beck’s work invites to think about what happens when there is no rational development or control over the economy and the negative consequences this has for the social environment.

Another important debate for this investigation concerns precarious work in the cultural sector. Discussions around this issue abound and precede the COVID-19 pandemic. Since 1990s, academics have noted that in post-Fordist societies the percentage of people in unstable employment has grown (Castel, Citation1997; Harvey, Citation1992; Standing, Citation2011) and production systems, labour market dynamics and the way people organise their work have also changed. In this context, the cultural sector of the capitalist economy has expanded, yet a key question remains: under what working conditions have creative economies developed? Waite (2009; cited by Comunian & Lauren, Citation2020) points to the fact that new precarious working conditions have affected workers from two sides of the labour market: low-paid workers, who are now part of the gig economy (De Stefano, Citation2016) and also the better-paid, highly skilled workforce of the creative economy (Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sports, Citation2016). In the global South, this entrepreneurial discourse of cultural and artistic work has also been scrutinised (Guadarrama, Citation2014, Citation2019; Guadarrama et al., Citation2021; Mauro, Citation2020), showing that precariousness is a condition of cultural labour that is widespread in the different spheres of artistic and cultural work, characterised by informal, unstable and low-income jobs.

In this sense, the notion of platform capitalism (Srnicek, Citation2016) can help us think how cultural work changes in relation to technological development. Particularly when the digitalisation and virtualisation of artistic work becomes part of gig economies (Kessler, Citation2019). We understand platforms as digital infrastructures that allow two or more groups to interact. It is a new business model that has evolved into a new and powerful type of company, which relies on the extraction and use of data. Users’ activities become the natural sources of raw material, which, like oil, is extracted, refined and used in diverse ways. We will see that the impossibility for performing artists to work on in cultural venues and on the street pushed them to use virtual platforms and social networks as a way of sustaining their activity. If established musicians were already using streaming platforms such as Spotify, this practice became even more widespread. In view of the monopoly of digital platforms, the rules governing royalty collection – the number of times a song must be played in order to get paid – was a topic of discussion among musicians in the independent scene, particularly how unequal this situation is for the sector. In the words of Valdez (Citation2020, n/p, author’s translation), “the confinement of people to their homes made reality, virtuality, and technological applications even more essential for living”, as the next sections will further discuss.

Methodology

We approached the impact of the COVID-19 crisis on self-employed performing artists from a sociological, and particularly, a cultural work and creative labour perspective (Alacovska & Gill, Citation2019; Banks, Citation2007, Citation2017; Hesmondhalgh & Baker, Citation2011), using a qualitative research strategy as we were primarily interested in how the pandemic was experienced by freelancing cultural workers. We sought to complement – rather than replicate – the array of large-scale surveys about the impact of COVID-19 on the arts, culture and the creative economy. A recent meta-analysis of some of these surveys (Comunian & Lauren, Citation2020) pointed out the invisible issues that aren’t captured by such tools though still need to be addressed, such as structural issues, demographic data of participants, and the future sustainability of work in the sector.

Our research was funded by the British Academy (Special Research Grants: COVID-19) and carried out by a team of three researchers from Goldsmiths, University of London and the University of Buenos Aires. We engaged 73 self-employed artists, both emerging and established, from London and Buenos Aires, through in-depth interviews and focus groups conducted virtually (Microsoft Teams). Fieldwork was carried out between November 2020 and November 2021 using a purposive sample to ensure diversity across gender, age, ethnic group, artform, and career stage, working across different workspaces (the street, the pub, the cultural centre, the mainstream theatre, event venues and big concert halls). In qualitative research, purposive sampling allows the seeking out of participants with specific characteristics to address the needs of a particular research project (Lewis-Beck et al., Citation2011). Artists were identified through networks of contacts, snowballing and social media posts. Selection criteria were three-fold: participants needed to be performing artists, work as self-employed (by own identification according to number of hours spent in a year and percentage of income), and be based or work in Buenos Aires or London.

We conducted 20 in-depth, semi-structured interviews, half in each city, with performing artists (10 women, 10 men), aged 25–45 years old, and at different career stages (the majority had between 15 and 20 years of performing experience, with 6 artists under 10 years and 2 under 5). Interviewees included: two opera singers, three actors, two circus artists, two pianists, one stand-up comedian, one beatbox performer, three dancers and six musicians (including four singers). Additionally, we ran 12 focus groups (one and a half hour long) with around 5 artists each, working in theatre, dance, music, circus and opera. Two of the focus groups included artists from both countries.

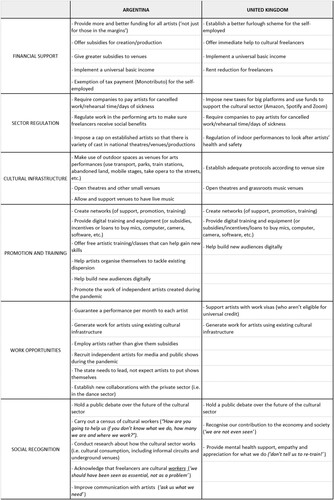

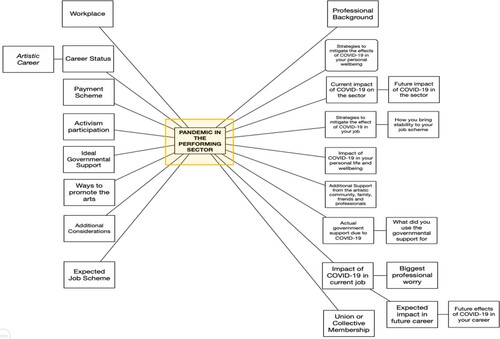

In terms of data analysis, all conversations were audio and video recorded, after obtaining informed consent and fully transcribed. We used NVivo for setting a coding frame using thematic analysis to create nodes based on questionnaire design, as shows. These initial nodes were developed around the topics of the interview questionnaire and were used for organising and comparing interview responses. We ended up with a significant amount of topics for the analysis and narrowed these down to a smaller number of nodes to facilitate the analysis. Out of these codes, we selected key dimensions for the focus group and also used thematic images to trigger the group discussion. Through content analysis, we examined emerging themes, group interaction and responses and debate about the selected images.

Figure 1. NVivo codes used for the data analysis showing the various dimensions explored in our interviews with self-employed performing artists.

At the end of our fieldwork, we organised two interactive policy workshops, one in Buenos Aires and another in London, to present research findings and discuss the role of cultural policy in the post-pandemic recovery of the sector. The events brought together cultural policymakers, industry representatives, academic experts, independent artists, cultural collectives and early career researchers. We discussed priority areas for policy intervention and issues and obstacles for their implementation, such as financial conservatism, existing sector divides and a lack of understanding of the value of the performing arts.

Cultural policy support

With regards to governmental support, there were several mechanisms of financial aid for those working in culture, the arts and the creative industries. In the UK, the largest scheme offered was the Cultural Recovery Fund, an initiative of £1.57 billion to mitigate the COVID-19 impact on cultural organisations. Additionally, self-employed cultural workers could apply for the Self-Employed Income Support Scheme, providing grants of up to £5160 for three months. For those not eligible, the Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme was available when operating with PAYE schemes. There was also tax relief and universal credit. The Arts Council National Lottery Project Grants increased their funds of £18 million to £75 million. Arts Council England re-opened their fund “Developing your creative practice”, increasing their budget from £3.6 million to £18 million.

Alongside public funds, industry organisations provided financial support to their members. These included, for example, the COVID-19 Film and TV Emergency Relief Fund, Livework for live performances, and the Directors Charitable Foundation grants. The Musicians Union Hardship Fund offered individual grants and the Actors’ Benevolent Fund helped actors and stage managers. Fleabag Support Fund and Theatre Community Fund were available for those working in the theatre industry, and the Royal Variety Charity helped cultural workers in the entertainment industry.

Whilst the UK government’s response to the arts was seen as being “too slow” and “too vague” and even accused of jeopardising the future of the cultural sector (Bakere, Citation2020), the UK had their highest increase in public sector expenditure on cultural services. While the average annual spending from 2009 to 2019 was £4 billion, the volume spent in the fiscal year 2020/21 increased up to £5.17 billion, 26.1% above the previous year. Later, in 2021/22, the UK spending dipped by 11.8% to £4.55 billion but remained above the average of the previous ten years (HM Treasury, Citation2022), inflation notwithstanding. While these statistics show the UK government’s financial commitment to the cultural sector, they also suggest a problem with the timing and distribution of funds, which did not reach most freelancers in the performing arts.

In the case of Argentina, support was mainly financial and was organised around specific artforms within the cultural sector. For example, Nuestro Teatro, an initiative from the Ministry of Culture, allocated £20,000 to create a competition based on short theatre performances. Cervantes OnLine provided a platform for old and new theatre productions. Additionally, Plan AmpliAR Podesta provided support to theatre venues in two rounds (2020 and 2021). Fondo Desarrollar was another initiative supporting cultural centres with operational costs for more than £2.1 million. Fortalecer Cultura offered financial support to cultural workers for up to £98 per month, during October, November and December 2020. There were also loans for SME companies in the cultural sector for up to £46,000, a joint initiative between the Ministry of Productive Development, the Ministry of Culture and the National Bank to distribute almost £5 million. Sostener Cultura was conceived as a one-off transfer for up to £197 by the Ministry of Culture for artists in vulnerable situations. Finally, in 2020 Puntos de Cultura tripled their budget to more than £650,000 to mitigate the effects of COVID-19 on cultural community organisations around the country.

The different measures takenFootnote1 in the UK, with a more “relaxed” and later lockdown, and Argentina’s very strict and earlier lockdown, reveal different policy challenges going forward. In contrast to the UK, Argentina had a quick response providing emergency funds for the cultural sector, especially for the most vulnerable workers, informed by a politics of solidarity and care. However, even though cultural policy support – underpinned by a view of culture as a social good – was offered to mitigate the pandemic’s immediate effects, it had no sustainable strategy in the long-term to reactivate the sector (Moguillansky, Citation2021; Serafini & Novosel, Citation2021).

Impacts and coping strategies

Impact of COVID-19 on people’s lives and livelihoods

The COVID-19 pandemic has had different impacts on our participants’ lives, work and industry, both in the short and the long term. Lockdown restrictions affected artists’ ability to do their jobs due to the closure of their workplaces, the cancellation of festivals and performances, and the impossibility to travel to international tours, concerts and events. The impact of the pandemic and the lockdown measures was strongly felt in their personal lives, affecting their mental health and their ability to plan and generate future work. This is in line with the substantive emotional labour that freelance workers in the performing arts, particularly musicians, need to put to handle precarious working conditions and ambiguous careers and positions (Nørholm Lundin, Citation2022). While some could see the benefits of staying at home for their artistic production, others felt deeply frustrated by the impossibility of connecting with audiences face-to-face, rehearsing with others or performing from the stage.

On personal life: “It’s been a roller-coaster”

The COVID-19 pandemic brought about unprecedented levels of stress, anxiety, worry, frustration and uncertainty to the lives of our participants. Feelings of sadness, hopelessness and loneliness permeated their narration of life during the pandemic. A sense of loss – of a career, of income, or of important events such as weddings, funerals and birthdays – made them feel uncertain, disoriented and disconnected from others. Those on their own particularly felt the lack of social interaction: “It’s been a roller-coaster, at the beginning it was quite tough because I live alone … Everything is solitude” (Opera singer, London). The disruption in social life and the physical distance, protocols and sanitary practices, led some to report episodes of social phobia or anxiety.

There were also financial concerns over the ability to keep paying rent as some feared not being able to provide for their families any longer. Many felt vulnerable and lacking protection in view of the precarious conditions of work under which they normally carry out their activities. There were cases of moving home (to the parents’ house, to a cheaper flat, to a more affordable city) due to lack of income, death of a relative or a breakup. Although there are descriptions of depression and despair, we have also heard positive stories of slowing down, reconnecting with family, taking a much-needed break, learning new skills and re-assessing life goals and priorities.

Not knowing when things would go back to normal led some artists to feel they needed to be ready and prepared to go back to the stage on short notice. But also fed into their uneasiness. The anguish of not knowing and not being able to perform on a stage affected self-perception and self-identity as an artist, “being is defined on stage” (Opera singer, Buenos Aires), and increased the sense of confusion, “We identify as singers and if we can’t sing then it’s difficult to know how to self identify. What are we if we cannot sing? (Opera singer, London). Some artists felt embarrassed in view of their precarious safety net: “there were like true feelings of guilt and shame, well I wasn’t prepared for this, my structure is very fragile, very, very weak” (Stand-up Comedian, Buenos Aires). This was translated, in some cases, into a lack of motivation to continue to carry out artistic work or feeling “empty” and with no direction. In their study of cultural workers, Warran et al. (Citation2022, pp. 11, 12) have found that the pandemic disrupts one of the core values previously seen as a key motivator for freelancers’ careers, that is, self-exploitation in exchange of freedom and creative autonomy. Workers shown a “change in perspective”, placing more emphasis on their personal lives outside work. In our study, this was mainly seen through self-assessment and reflection.

On current job: “We were left in a limbo”

Generally, research participants received no compensation for their lost/cancelled work, with a few exceptions where there was a contract in place. This, in turn, reproduces the existing hierarchy between those artists working as employees and those working as self-employed (Nørholm Lundin, Citation2022, p. 6). International tours, opportunities and plans got cancelled and so did all performances. The sudden interruption in work activities came as a complete shock. Some expressed anger at organisations for not taking responsibility and doing little or nothing to support them. They felt they were left in a limbo as freelancers.

Many of our interviewees lamented how the pandemic knocked down long-awaited contracts and great opportunities they had lined up after so many years of work. Although some work opportunities moved online, the frequency and amount diminished drastically (“from having 3, 4, 5 castings a week, I went to having just one a month”, Actress and Dancer, Buenos Aires) and the auditions format changed to self-tape or digital, so learning “the new rules of the game” was required. Many considered trying to find work outside the performing arts. This was seen as a need rather than a desire and a result of all their artistic work getting cancelled: “I started to think about working in radio and finding new ways of living because we don’t know how long this is going to last” (Contemporary dancer, Buenos Aires), “you need to start finding new possibilities to work outside the arts’ (Opera singer, London).

We saw endless personal rearrangements in a context of uncertainty, precariousness and lack of economic resources. In some cases, artists became aware of the vulnerability in which they always lived and of their limited financial resources to face extreme situations like the COVID-19 pandemic. They always lived as precarious workers, but this condition is now becoming conscious and leads, in some cases, to participate in collective actions and activism. In a few cases, a positive or entrepreneurial attitude appears in the face of adversity, using the lockdown for studying and acquiring new knowledge and skills.

Perceived impact on the sector and future career: “Nobody cares”

Pandemics bring a great level of disruption, angst and uncertainty to social life and this was expressed by our research participants, particularly when it comes to going back to work in the performing arts. The recovery of the sector – and of the country’s economy – the rescheduling of cancelled work and how audiences will behave post-pandemic were major causes of concern. Other challenges included maintaining a good mental health and wellbeing as part of “getting ready to go back to perform” and securing a share of social media attention and streaming platforms.

A sense of hopelessness permeated most views. In the case of Buenos Aires, existing dissatisfaction with the levels of government funding for the cultural sector affected how participants envisioned the post-pandemic recovery, as expressed by a Contemporary Dancer:

If there was no funding until this moment, I mean, less is there going to be now to be able to recover.

Why am I doing this if a lot of people are dying? Think about it, I'm making a video and then emotions and things cross my mind, so why am I doing this if I don't know what's going to happen to the world?

Why coronavirus is a perfect storm is because everyone has a different second or third job … Whatever it is, all is freelance. All of it is zero hours and so they all collapsed, and everyone had a bad time.

The question of funding has become central to the survival and meaning of artistic careers. There is also evidence of greater restriction and austerity in lifestyles. This new adjustment pushes to rethink continuously and live in a permanent redefinition. The need to “re-think yourself” or “re-plan your career” was expressed by a few artists. The future was perceived in a negative way and the question of virtuality, so present daily during the pandemic, will endure as a resource, particularly for consecrated artists, despite fears about the prevalence of technology over face-to-face performances. Problems with casting and representation and the increase of self-tapes, during and after the pandemic, were also issues of concern about the future of theatre in the UK.

In Argentina, some interviewees spoke of long-lasting impact of the pandemic on the performing arts and state neglect in supporting the recovery of independent theatre or opera, for example. The lack of state support in the first phase of the pandemic was seen as leading to the permanent closure of independent venues. On a more positive note, the re-appropriation of public space and parks in Buenos Aires offered alternative performing stages. Similarly, digital innovation was welcomed in the sector. Beyond traditional ways of doing theatre there was the hope that streaming will continue to reach wider and more international audiences. In the UK, Brexit was perceived as a bigger threat than COVID-19, with its negative impact on international artistic collaboration, exchange, touring and auditions. As artists found it hard to imagine work in the long-term, a focus on living day-by-day seemed more attainable.

Artists’ coping strategies

We can define three strategies to mitigate the effects of COVID-19 on the personal/subjective situation of performing artists. Firstly, the importance of virtual platforms is recognised as a way of continuing to have a social life and developing creative activity. Secondly, the context of closure and impossibility of acting in the performing arts was perceived as an opportunity to boost creativity, in the cases of those not submerged in depression. What to do with oneself when the others do not “exist”? Those who manage to have an active attitude towards the lockdown’s impact have taken advantage of the time to compose, create, paint and learn:

I was also able to take advantage of the extra time to study, to do things around the house that I hadn't been able to do … and also to take courses, I have taken music courses, several virtual ones, so I made good use of the time [in the pandemic]. (Pianist, Buenos Aires)

At least I’m grappling with the question of who am I and what am I doing in the world and what’s it all about, you know … if I’m engaged in that question in a healthy way then that’s what I need from life and if I don’t have that, then that’s when I’m not coping. (Socially engaged artist and musician, London)

The relevance of virtual platforms as an opportunity to turn around artists’ activities and sometimes to have alternative job options is undeniable. The question of artistic financing through these platforms also arose. We observed two main ways of financing, one through teaching, another, through generating and commercialising content on platforms such as Instagram, Patreon, Bandcamp and Facebook. Not only did artists give classes but also take them up to learn and enhance their skills and practices, mainly related to new technological knowledge (data science, programming, video editing). Nonetheless, the virtualisation of everyday life during the pandemic was entangled with resistance (“I refuse to go online”), limited broadband and connection issues, hope (“the solution was in the virtual”) and self-learning (“I ended up becoming an expert in self-tapes”), making the world feel smaller by reaching new audiences and connecting with others more easily, both locally and internationally.

Discussion: suggestions for cultural policy actions

Our research participants acknowledged there was public support available both in Argentina and the UK and that governments developed a contingency plan to absorb the financial impact of the pandemic. Those artists who received financial aid found it helpful to cover part of their bills. However, some artists from Buenos Aires applied for support and were not selected because the target audiences were people in a more deprived situation. Many artists in the UK, in contrast, decided not to apply for emergency funds as preferred to leave the funding to those in a worse economic situation.

Overall, our participants showed disappointment with the level of governmental support:

I would have liked for them to have supported the venues that we would like to go back and play in. I’m pretty sure most of those places are closed for good. They did not try to help those people. They let them go to the wall and in letting those businesses fail they have failed us. (Actress, London)

I would ask for everything, but I don’t expect anything given the current circumstances. (Actress, Buenos Aires)

Three key areas stand out for post-pandemic cultural policy support in both countries: universal basic income (UBI), state regulation of the sector and digital training. While public discussions about UBI in the UK acquired greater centrality during/after the pandemic, particularly with Ireland’s adoption of a pilot scheme for artists in 2022 and advocacy in the sector (e.g. the Musicians’ Union), in Argentina this subject is restricted to the margins rather than being in the public domain. State regulation of major digital platforms remains a persistent demand from cultural workers, particularly concerning the protection of copyright. This was a recurrent theme among independent musicians. In Argentina, new digital platforms have emerged in the film industry, such as Cine.Ar which became very successful during the lockdown, and in the music industry, with new startups such as Bea aimed at making visible and monetising the work of independent musicians from the South. Similarly, new digital training networks and opportunities have been created by Argentina’s Ministry of Culture after the pandemic, particularly addressing gender issues and developed in partnership with universities.

It is evident in these suggestions that financial support is necessary but not enough. Self-employed and freelancing artists want governments to provide mental health support, technical training and easier access to digital equipment. In the UK, there was a greater concern with mental health, whereas in Argentina access to the digital was seen as a more pressing need, particularly in view of the high cost of internet connection and the technical issues with the quality of the network. The sense that “the government doesn’t care about culture” was strongly present in both countries. This can be explained not only in view of the situation of crisis from which participants were speaking, but also – particularly in Buenos Aires – linked to pre-pandemic dissatisfaction with levels of public funding in the cultural sector. The work of unions, charities and collectives, such as Help Musicians in the UK and SAGAI in Argentina, was praised by some artists for their support during the pandemic.

We have seen that lockdown approaches differed in both countries. In Argentina, the long quarantine revealed the fragility of the independent cultural sector, since several spaces did not reopen their doors. The policy responses of both countries unveiled that they do not know the cultural sector in all its dimensions; it is, therefore, necessary to think of future policies in which artists actively participate in their formulation and implementation. Artists demand access to new technologies, continuous training, help in promoting their activities. In emergency situations, performing artists need further support, such as help with the dissemination of cultural productions via platforms and safeguarding their performing rights and copyrights.

Argentina’s economic situation has been very critical for several years, in terms of the value of the currency in relation to the dollar and the high inflationary levels that affect daily life. It is understandable that in this situation artists complain and demand further increases in subsidies. This affects both emerging and established artists, since even those who receive a salary, saw it deteriorating with the currency devaluation. Ultimately, these suggestions show the need for cultural policy to include artists’ voices and the sectors’ needs in the implementation of emergency support schemes, but also in the formulation of longer-term strategies.

During the policy workshop discussions, stakeholders in Argentina were concerned about the future of the cultural sector in view of existing inequalities, particularly the social exclusion of underprivileged artists. Producing relevant cultural data particularly about freelancers and providing adequate financial support remain major challenges for cultural policy. The key role of resistance in the sector – apart from resilience – was seen as an important feature of how grassroots organisations responded to the pandemic, organising themselves to demand further support and public recognition. In the UK, workshop participants put forward other ideas: creating freelancers’ networks, offering pastoral care to artists, launching a scheme such as “Eat out to help out” to encourage audiences to return to theatres and other venues, and making funding more accessible to independent workers.

Our research highlights the need to provide substantial and multi-faceted cultural policy support to freelancers in the performing arts, ranging from digital training to mental health support and financial aid. This reinforces the finding that new funding should focus on supporting freelancers in the creative industries (Chamberlain & Morris, Citation2021). The comparative angle of the research allowed us to see that the precarious nature of cultural work was similarly experienced in these very different cities. Self-employed artists both in the UK and Argentina felt abandoned, forgotten and neglected during the pandemic. However, these different countries’ institutional, political and economic arrangements resulted in different levels of financial support, lockdown restrictions and returning to work protocols, which in turn present different challenges for the post-pandemic recovery of the cultural sector. For Argentina, an indebted state with rocketing inflation, salary stagnation and increasing poverty; in the UK, a Brexit landscape of restricted mobility and fewer opportunities for international collaborations.

Conclusion

This article has offered an analysis of performing artists’ lived experiences of lockdown and suggestions for how cultural policy can aid the recovery of the performing arts. Using a purposive sample, we carefully selected artists from a variety of sectors to compare their experiences of work disruption, what support they received and what alternative activities were available to them. We made a number of decisions at the outset of this research project: first, that we would focus on the most vulnerable in the creative economy; second, that we would collect primary, qualitative data to complement ongoing surveys in the sector; third, that we would focus on individual workers rather than organisations; and finally, that we would bring together two different national contexts to illuminate differences in cultural policy responses to lockdowns.

Not falling in the “restricting and territorialising trap” of only comparing similar cities (Robinson, Citation2016, p. 5), we have sought to compare and contrast two very different cities; London and Buenos Aires. This was to reveal how existing different levels of public and private support as well as precarious work conditions shape different responses and experiences of the pandemic. For example, in the case of Argentina we saw a state having to manage a severe economic crisis alongside an exploding and seemingly uncontrollable pandemic with a hostile media contesting key public health measures. In contrast, we saw in the UK a stronger institutional apparatus with considerably larger financial resources, a quick and efficient vaccination roll out butting up against the context of Brexit.

Although there is informality and structural precariousness in the cultural sector of both countries, the performing arts in Argentina suffered a more serious situation and received less support than in the UK. Artists were already doing a variety of jobs in addition to their artistic activity as complementary livelihoods. Argentina more than the UK, prioritised other areas of the economy over the cultural sector. In the UK, however, there was greater concern about the restrictions imposed on mobility (tours, exchanges and residences), not only due to the pandemic but as a consequence of Brexit.

Regarding digital migration, Argentina was slower to adapt because of infrastructure and connection barriers, confirming the findings of the UNESCO’s report (Citation2021, p. 7) showing how the digital divide puts certain countries on an unequal footing with other parts of the world. In the UK said migration was more fluid, although not completely straightforward (“livestreaming is hard to think about, difficult to film and you need expertise to edit”, Actor, London). The opening generated by digitalisation brought greater opportunities in Argentina, since it allowed an internationalisation of collaborations and audiences, whereas in the UK, this opening had been already established. Our study revealed a positive attitude in relation to the appropriation of virtual tools for artistic practices. Although many of the performing artists, except for musicians, appeared to be reluctant to adopt digital practices, in general they ended up learning how to use these devices to continue developing their work activities. We identified three key trends:

Greater possibilities: The impossibility of staging theatre, music, dance and circus pushed performing artists to resort to the digitalisation of their activity, a process that already existed in other social and labour spheres. Social networks became a channel for disseminating and making the artists’ performances visible, not only to display their creations, but also to be in the public arena. However, artists are aware of the exclusions, contradictions and inequalities inherent to mainstream digital platforms, which pose challenges particularly for emerging artists.

New stages: The virtual realm became a public space. Artists made short plays on YouTube, musicians made recurring Instagram Lives, and actors and dancers rewrote their scripts for an online context. This wasn’t always smooth and without hesitation, expressing some of the tensions and contradictions of using social media platforms in a culture of connectivity (Van Dijck, Citation2016).

New roles for audiences: A new type of performance was thus created, the artistic event was modified and a new mode of presentation of the artists in relation to the public, now essentially virtual, was produced.

These trends refer to the digital ecosystem that artists are facing and will encounter in the future, not only considering streaming platforms as performing stages and social media as the new scenario for promotion and marketing, but also potential extensions, such as the metaverse, which could allow artists and audiences to redefine their role in the art world. Moreover, the future of digital performances can be the next opportunity to help emerging artists, especially those from the global South, get ahead and unsettle the hegemonic position of those well-established artists from the global North. Ultimately, the goal would be to develop a more democratic cultural space, with reduced barriers for new upcoming artists and equal opportunities for cultural workers, regardless of their social, geographical or economic background.

Freelancers’ accounts of the future of the performing arts are generally pessimistic. The gloomiest views come from those in Argentina who fear the changes brought about by the pandemic will lead to the permanent closure of small venues and companies, with a dramatic impact on the future of certain art forms, such as opera or independent theatre. As other studies have shown (Capasso et al., Citation2020; Guadarrama et al., Citation2021; Mauro, Citation2020), the precarity of the performing arts and the permanent closure of independent cultural venues co-existed with the unprecedented profits made by large global digital companies during the pandemic. In the UK Brexit is to blame for the worst yet to come, with travel restrictions and new visa requirements affecting international collaboration.

We also heard about fears of new pandemics hitting society in future years. In this uncertain and risky global context, we hope our study has shown that multidimensional cultural policy support is needed (from financial aid to promotion and training, as well as mental health support) to help self-employed performing artists stay and thrive in their careers. Above all, for public policy to support cultural workers beyond merely celebrating their creativity rhetorically, a public, concrete recognition of the value of their work in society is what is needed most.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 With a 67.8 million population, the UK had 179,217 COVID-related deaths to date, and Argentina, with 45 million population, 128,973 COVID-related deaths, according to Worldometers (2022).

References

- Alacovska, A., & Gill, R. (2019). De-westernizing creative labour studies: The informality of creative work from an ex-centric perspective. International Journal of Cultural Studies, 22(2), 195–212.

- Bakere, L. (2020). Government too late for UK culture sector in Covid-19 crisis, say MPs. The Guardian, July 23. https://www.theguardian.com/culture/2020/jul/23/government-too-late-for-uk-culture-sector-in-covid-19-crisis-say-mps

- Banks, M. (2007). The politics of cultural work. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Banks, M. (2017). Creative justice: Cultural industries, work and inequality. Rowman and Littlefield International.

- Banks, M., Gill, R., & Taylor, S. (2012). Theorizing Cultural Work Labour, Continuity and Change in the Creative Industries. Routledge.

- Banks, M., & O’Connor, J. (2021). “A plague upon your howling”: Art and culture in the viral emergency. Cultural Trends, 30(1), 3–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/09548963.2020.1827931

- Bauman, Z. (2007). La Sociedad Individualizada. Cátedra.

- Beck, U. (1992). Risk society : Towards a new modernity. Sage.

- Brooks, S., & Patel, S. (2022). Challenges and opportunities experienced by performing artists during COVID-19 lockdown. Scoping Review, Social Sciences & Humanities Open, 6(1), 100297. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssaho.2022.100297

- Capasso, V., Camezzana, D., Mora, A. S., & Sáez, M. (2020). Las artes escénicas en el contexto del ASPO: Demandas, iniciativas, políticas y horizontes en la danza y el teatro. Question/Cuestión, 2(66), e470. https://doi.org/10.24215/16696581e470

- Castel, R. (1997). “La Sociedad Salarial” en: La Metamorfosis de la Cuestión Social. Una Crónica del Salariado. Paidós.

- Chamberlain, P., & Morris, D. (2021). The Economic Impact of Covid-19 on the Culture, Arts and Heritage (CAH) Sector in South Yorkshire and Comparator Regions. University of Sheffield.

- Comunian, R., & Lauren, E. (2020). Creative and cultural work without filters: Covid-19 and exposed precarity en the creative economy. Cultural Trends, 116–128.

- Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sports. (2016). Creative Industries Economic Estimates January 2016. https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/creative-industries-economic-estimates-january-2016

- De Stefano, V. (2016). The rise of the "just-in-time workforce": On-demand work, crowdwork, and labor protection in the "gig-economy". Comparative Labor Law and Policy Journal, 37(3), 471. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2682602

- Giddens, A. (1999). Consecuencias de la modernidad. Editorial Alianza.

- Gill, R., & Pratt, A. C. (2008). In the social factory? Immaterial labour, precariousness and cultural work. Theory, Culture & Society, 25(7-8), 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263276408097794

- Guadarrama, R. (2014). Multiactividad e intermitencia en el empleo artístico. El caso de los músicos de concierto en México. Revista Mexicana de Sociología, 76(1), 7–36. México, D.F. Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México-Instituto de Investigaciones Social. ISSN 2594-0651

- Guadarrama, R. (2019). Vivir del arte. La condición social de los músicos profesionales en México. Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana.

- Guadarrama, R., Bulloni, M. N., Segnini, L., Quiña, G., Pina, R., & Tolentino, H. (2021). América Latina: Trabajadores creativos y culturales en tiempos de pandemia [Latin America: Creative and cultural workers in times of the pandemic]. Revista Mexicana de Sociología, 83, 39–66. https://doi.org/10.22201/iis.01882503p.2021.0.60168

- Harvey, D. (1992). La Condición de la Posmodernidad. Capitulo II “Capitalismo Posfordista”. Editorial Amorrortu.

- Hesmondhalgh, D., & Baker, S. (2011). Creative Labour: Media Work in Three Cultural Industries. Routledge.

- HM Treasury. (2022). Public expenditure: Statistical analyses 2022. In Presented to Parliament by the Chief Secretary to the Treasury by Command of Her Majesty.

- Jones, S. (2022). Cracking up: the pandemic effect on visual artists’ livelihoods. Cultural Trends, 1–18. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/09548963.2022.2120382

- Kessler, S. (2019). Gigged. The Gig Economy. The End of Job, the Future of Work. Random House.

- Lewis-Beck, M., Bryman, A., & Futing Liao, T. (2011). Purposive sampling. In The SAGE Encyclopedia of Social Science Research Methods. Sage Publications. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781412950589

- Luhmann, N. (1995). Social Systems. Stanford University Press.

- Mauro, K. (2020). Arte y trabajo: indagaciones en torno al trabajo artístico y cultural. In Revista Latinoamericana de Antropología del Trabajo, 8. http://www.ceil-conicet.gov.ar/ojs/index.php/lat/article/view/739/586

- Moguillansky, M. (2021). La cultura en pandemia: de las políticas culturales a las transformaciones del sector cultural. Ciudadanías. Revista De Políticas Sociales Urbanas, (8). Recuperado a partir de http://revistas.untref.edu.ar/index.php/ciudadanias/article/view/1127

- Nørholm Lundin, A. (2022). “Where is your fixed point?” dealing with ambiguous freelance musician careers. Cultural Trends, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/09548963.2022.2075715

- Robinson, J. (2016). Thinking cities through elsewhere: Comparative tactics for a more global urban studies. Progress in Human Geography, 40(1), 3–29. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132515598025

- Ross, A. (2008). The New geography of work: Power to the precarious? Theory, Culture & Society, 25(7–8), 31–49. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263276408097795

- Serafini, P., & Novosel, N. (2021). Culture as care: Argentina’s cultural policy response to COVID-19. Cultural Trends, 30(1), 52–62. https://doi.org/10.1080/09548963.2020.1823821

- Spiro, N., Perkins, R., Kaye, S., Tymoszuk, U., Mason-Bertrand, A., Cossette, I., Glasser, S., & Williamon, A. (2021). The effects of COVID-19 lockdown 1.0 on working patterns, income, and wellbeing among performing arts professionals in the United Kingdom (April-June 2020). Frontiers in Psychology, 11(2020), 594086–594086. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.594086

- Srnicek, N. (2016). Platform Capitalism. Polity Press.

- Standing, G. (2011). The Precariat. The new Dangerous Class. Bloomsbury.

- Szpilbarg, D., & Saferstein, E. (2016). De la industria cultural a las industrias creativas: un análisis de la transformación del término y sus usos contemporáneos. Estudios De Filosofía Práctica e Historia De Las Ideas, 16(2), 99–112. http://qellqasqa.com.ar/ojs/index.php/estudios/article/view/75

- UNESCO. (2021). Cultural and Creative Industries in the Face of COVID-19: An Economic Impact Outlook. UNESCO.

- Valdez, X. (2020). Las plataformas son las grandes ganadoras de la pandemia. Es hora de discutir su regulación. https://cenital.com/las-plataformas-son-las-grandes-ganadoras-de-la-pandemia-es-hora-de-discutir-su-regulacion

- Van Dijck, J. (2016). La cultura de la conectividad actual. Una historia crítica de las redes sociales. Chapters: 1, 2(8). Siglo XXI Editores.

- Walmsley, B., Gilmore, A., O’Brien, D., & Torregiani, A. (2022). Culture in Crisis: Impacts of Covid-19 on the UK Cultural Sector and Where We Go from Here. Centre for Cultural Value.

- Warran, K., May, T., Fancourt, D, & Burton, A. (2022). Understanding changes to perceived socioeconomic and psychosocial adversities during COVID-19 for UK freelance cultural workers. Cultural Trends. Advance once publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/09548963.2022.2082270